|

|

The Great Utopia : The Russian and Soviet Avant-Garde, 1915—1932. — New York, 1992The Great Utopia : The Russian and Soviet Avant-Garde, 1915—1932 / The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York; State Tret'iakov Gallery, Moscow; State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg; Ministry of Culture of the Russian Federation. — New York : Published by the Guggenheim Museum, 1992. — ISBN: 0-89207-095-1

During the years 1915–32, Moscow and Petrograd (from 1924, Leningrad) witnessed revolutions in art and politics that changed the course of Modernist art and modern history. Though the great revolution in art—the radical formal innovations constituted by Vladimir Tatlin's “material assemblages” and Kazimir Malevich's Suprematism—in fact preceded the political revolution by several years, the full weight of the new expressive possibilities was felt only after, and to a large extent because of, the social upheavals of February and October 1917. As avant-garde artists, armed with new insights into form and materials, sought to realize the utopian aims of the Bolshevik Revolution, art and life seemed to merge.

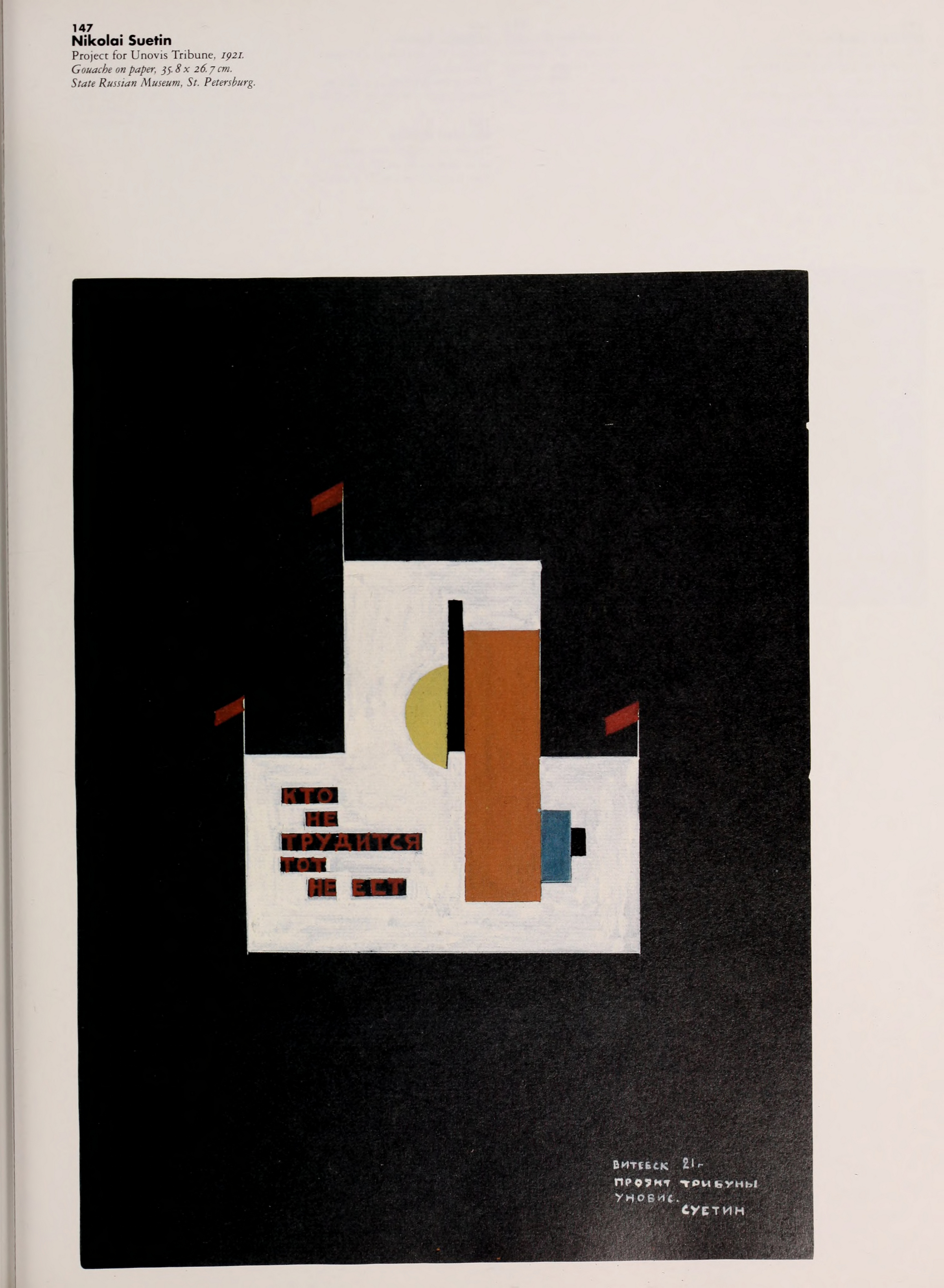

In this volume, which accompanies the largest exhibition ever mounted at the Guggenheim Museum, twenty-one essays by eminent scholars from Germany, Great Britain, Russia, and the United States explore the activity of the Russian and Soviet avant-garde in all its diversity and complexity. These essays trace the work of Malevich's Unovis (Affirmers of the New Art) collective in Vitebsk, which introduced Suprematism's all-encompassing geometries into the design of textiles, ceramics, and, indeed, whole environments; the postrevolutionary reform of art education and the creation of Moscow's Vkhutemas (Higher Artistic-Technical Workshops), where the formal and analytical principles of the avant-garde were the basis of instruction; the debates over a “proletarian art” and the transition to Constructivism, “production art,” and the “artist-constructor”; the organization of new artist-administered “museums of artistic culture”; the “third path” in non-objective art taken by Mikhail Larionov; the return to figuration in the mid-1920s by the young artists—and former students of the avant-garde—in Ost (the Society of Easel Painters); the debates among photographers, in the late 1920s and early 1930s, on the superiority of the fragmented or continuous image as a representation of the new socialist reality; book, porcelain, fabric, and stage design; and the evolution of a new architecture, from the experimental projects of Zhivskul‘ptarkh (the Synthesis of Painting, Sculpture, and Architecture Commission) to the multistage competition, in 1931—32, for the Palace of Soviets, which “proved” the inapplicability of a Modernist architecture to the Bolshevik Party's aspirations.

More than seven hundred of the finest examples of Russian and Soviet avant-garde art are reproduced here in full color. Drawn from public and private collections worldwide—notably, from Baku, Kiev, Moscow, Riga, Samara, St. Petersburg, and Tashkent in the former Soviet Union—these works are by such masters as Natan Al'tman, Il'ia Chashnik, Aleksandra Ekster; Gustav Klutsis, El Lissitzky, Liubov' Popova, Ol'ga Rozanova, Georgii and Vladimir Stenberg, and the Vesnin brothers.

Preface

Even on purely stylistic and formal grounds, the Russian and Soviet avant-gardes contribution to Modern art merits the scale and depth of the present exhibition. Kazimir Malevich and Vladimir Tatlin, the avant-gardes leaders, brought Modernism to its logical conclusions even as they first fully internalized and reinvented it in a Russian context. Yet those ideas became starting points. The laboratory of Constructivist and Suprematist experiments yielded visual inventions that still influence art, architecture, and design.

In his Chernyi kvadrat (Black Square, 1915), Malevich resolved the Modernist struggle to reduce form to its essence; and when, for the 0.10 exhibition (Petrograd, 1915—16), the artist hung the work in the place traditionally reserved for a religious icon, he aspired to replace the existing order with a new artistic ideal. Reinterpreting European Cubism, Malevich applied the abstracting process to reduce the substance of the world to primary forms, revealing an entirely other dimension—an absolute, non-objective world. With his Kontr-rel'ef (Counter-Relief, 1914—15), Tatlin took the fractured planes of Cubism in a different but still logical direction—into real tangible space.

Somewhere between the absolute spiritual idealism of Malevich’s Suprematism and the dramatic reality of Tatlin’s reliefs is that utopian sensibility, within a historical context of political and social upheaval, which released Russian art from the studio and onto the street, and which endowed it with a desire to pervade every aspect of life—even to become an agent of social change.

The term “utopia” carries with it the spirit of the avant-garde’s project to place art at the service of greater social objectives and to create harmony and order in the chaotic world around them. Given the course history has taken in Russia in the twentieth century, “utopia” also has connotations of impracticality; idealism is good in theory, but not in practice. Few images in the Russian avant-garde are more compelling than Tatlin’s construction of an Everyman’s flying machine, Letatlin (1929—32), intended to be the utilitarian marriage of art, science, and technology—now, as a historical relic, it recalls the legend of Icarus, who flew too close to the sun.

One thing that can be gleaned from the scant but growing critical analysis of the Russian avant-garde—the “Great Experiment,” as pioneering art historian Camilla Gray called it—is that single interpretations are impossible to maintain. Essential questions persist, relevant to our own predicament: What is the potential for art—an essential ambition of the avant-garde—to infiltrate and transform everyday life? Have traditional painting and sculpture, as Rodchenko proposed, reached the end of their cultural development in favor of more utilitarian communications media and practical arts? What is the relationship between art and politics? Can an aesthetic pluralism be established and institutionalized?

In planning the exhibition, we identified three primary phases of the avant-garde in Russia:

Our exhibition, The Great Utopia, attempts to map out the vast territory of vanguard artistic production in Russia, beginning in 1915 with the 0.10 exhibition, where Malevich’s square and Tatlin’s relief were first shown, and ending in 1932 with the competition for the Palace of Soviets in Moscow and the First Five-Year Plan, at which time the “left wing” in art lost credibility in the face of Stalin’s stern program to build an industrialized Soviet Union.

At its core, the exhibition emphasizes the utopianism of the vanguard project, the tensions between radical affirmations of the autonomy of art and the projection of aesthetic concerns into daily life through design; the exhibition attempts to contextualize issues of style by emphasizing the institutional and ideological foundations for much of the production of vanguard work.

By representing the plurality of approaches to utopian abstraction, the curators demonstrate the essential continuity of the vanguard project before and after the Revolution, in terms of individual artists’ contributions and in their collective (and competitive) struggle to play leading roles in the formation of a new consciousness.

This exhibition presents a nearly complete sample of the artistic documents of the Russian and Soviet avant-garde—laid out in all of their diversity, beauty, and contradictions. The exhibition encompasses almost all media, with the notable exception of film, which it was not possible to exhibit because the renovation of the Guggenheim Museum theater has been postponed. No exhibition on the topic has included such a comprehensive representation of artists and of works drawn from so many collections. Seventy percent of the objects were borrowed from Russian museums and private collections, as well as from museums in Uzbekistan, Azerbaijan, Ukraine, and Latvia. Many of the works on view are being seen for the first time by American and European audiences.

The scale of the exhibition is a function of an urgent need we felt for the full scope of the period to be presented at once, for the benefit both of the devoted scholars and students of the avant-garde who continue to define its complex history and circumstances and of a larger public that will be able to comprehend the breadth and the uniqueness of this movement in the history of art.

The task of assembling such a broad range of material from such a wide range of sources demanded a unique organizational structure. Obviously, no single curator commands a detailed expertise encompassing all of the works and their myriad locations, many of them obscure. A number of sources had to be combined simply to create a working checklist from which to draw a final selection.

In addition, since the history of the avant-garde in Russia, in comparison to the history of European Modernism, is still in part uncharted, no single interpretation is dominant. From its inception, the exhibition necessarily demanded a variety of perspectives in order to select and shape its content.

The team of curators and experts appointed in June 1989 defined the conceptual guidelines for the exhibition and culled working lists of literally thousands of objects from Western and Russian public and private collections. The team of museum and independent curators from Russia, Germany, and the United States—Vivian Endicott Barnett, Christiane Bauermeister, Charlotte Douglas, Svetlana Dzhafarova, Hubertus Gassner, Evgenii Kovtun, Irina Lebedeva, Evgeniia Petrova, Alla Povelikhina, Elena and Vasilii Rakitin, Jane A. Sharp, Anatolii Strigalev, and Margarita Tupitsyn—was chosen to encompass a variety of specializations and backgrounds. Over a period of almost three years and in meetings in Moscow, St. Petersburg, Frankfurt, and New York, the lists were narrowed down to a group of over 900 works that the curatorial team felt would provide the most comprehensive and coherent overview of the period.

It was also a post-Cold War spirit of collaboration that inspired our effort to structure a project that would be a joint venture of American, European, and Soviet/Russian expertise and organizational foundations. The idea originated in the spring of 1988, when Eduard Shevardnadze, then Soviet Foreign Minister, toured the Guggenheim. That summer in Moscow, a first official protocol was created to initiate the project.

As the exhibition was being organized, the Soviet Union underwent the most dramatic and overwhelming changes since the Bolshevik Revolution. With the emergence of perestroika, a great sense of optimism fueled the establishment of the exhibition as a joint East-West venture. Further changes in Russia meant the reorganization of cultural as well as governmental bureaucracies, which could have halted the project, were it not for the patience, dedication, and communication of all of the institutions involved, including the continued participation of the Russian (formerly Soviet) Foreign Ministry represented especially by Anatolii Adamishin, now Ambassador to Italy, and by Vladimir Petrovsky, Under-Secretary General of the United Nations, whose deep involvement with international cultural issues dates at least to his attendance at the inauguration of the Guggenheim Museums Frank Lloyd Wright building in 1959.

The two major Russian museums—the State Tret'iakov Gallery in Moscow, led by Iurii Korolev, and the State Russian Museum in St. Petersburg, led by Vladimir Gusev and Deputy Director Evgeniia Petrova—committed their staffs and their important collections to this exhibition. The Vuchetich All-Union Artistic Production Association (VUART)—under former Director Pavel Khoroshilov, Director Aleksandr Ursin, and Deputy Director Valentin Rivkind—took on the very difficult task of coordinating loans from over fifty provincial and other museums throughout the former Soviet Union. The Ministry of Culture of the Russian Federation—led by Minister Evgenii Sidorov and Head of Museum Department Vera Lebedeva—lent their critical official support and logistical assistance, as had the former Ministry of Culture of the USSR, led by Nikolai Gubenko with assistance from Genrikh Popov and Lidiia Zaletova.

Christoph Vitali, Director of the Schirn Kunsthalle, Frankfurt—one of the most prominent cultural institutions in Germany and also the first host of this exhibition—was the critical link in Europe in all aspects of negotiation and organization.

At the Guggenheim, all of the selection lists, research, loans, and catalogue contents were coordinated over the course of three years by a competent and specialized staff led by Jane A. Sharp, Project Associate Curator. With her curatorial expertise, impressive facility with the Russian language, and thorough approach to the exhibition’s organization on every level, Jane Sharp was the hub holding together the project’s many spokes. Natasha Kurchanova, Curatorial Assistant, managed the English/Russian database of thousands of objects and provided important research and loan coordination with the further assistance of Sabine Lange, Emily Locker, Katherine Glaser, and Nataliya Bregel. Linda Thacher, Associate Registrar, professionally handled the endless details and logistics of the international transport of objects. Erik Quam, Information Systems Analyst, designed and supported the database related to the works of art.

In Moscow, a parallel organization was coordinated at VUART by Svetlana Dzhafarova, Zel'fira Tregulova, and Faina Balakhovskaia, without whose professional work and tireless effort the exhibition simply would not have been possible. They, in concert with Deputy Director Evgeniia Petrova at the State Russian Museum and Curators Irina Lebedeva and Ekaterina Seleznova at the State Tret'iakov Gallery and representatives of other museums, coordinated the loans of all objects in the former Soviet Union.

The catalogue itself was a monumental and unique project begun over three years ago. The content, determined by the curatorial team, was intended to make the book a comprehensive reference that would be of value for years to come. Authors include not only members of the working group but such well-known scholars as Natal'ia Adaskina, Susan Compton, Nina Lobanov-Rostovksy, Christina Lodder, Aleksandra Shatskikh, and Paul Wood. Managing Editor Anthony Calnek oversaw the production of what is the most ambitious catalogue in the Guggenheim’s history. The editing of the book was handled with extraordinary skill and dedication by Jane Bobko. The talented American catalogue team also included Victoria Ellison, Associate Editor for the glossary, Robert Hemenway, copy editor, and Charles Davey, production and design consultant, as well as Research Assistant Kathleen Friello. Massimo Vignelli created the simple and elegant catalogue design in keeping with his new graphic system for the Guggenheim.

A complementary catalogue team worked in Russia, coordinated by Svetlana Dzhafarova, Zel'fira Tregulova, and Faina Balakhovskaia and including editors Andrei Sarab'ianov and Irina Sorvina.

The extraordinary design of the exhibition is due to architect Zaha Hadid, who, with Pamela Myers at the Guggenheim, made the exhibition accessible and provocative in the Frank Lloyd Wright space and new Gwathmey Siegel and Associates tower. The exhibition marks the first occasion on which the two spaces have been used as a single entity.

All in all, the exhibition touched almost every person in each of the organizing institutions in New York, in Russia, and in Frankfurt.

Perhaps most important, the exhibition is the product of the cooperation of lenders—museums and private collections. The State Tret'iakov Gallery and State Russian Museum treasures form the core of the exhibition, surrounded by works from Russia, Europe, and the United States. The central contribution from the collection of the late George Costakis, both from his estate and from the group of works he generously donated to the State Tret'iakov Gallery, deserves special note. Costakis, whose long association with the Guggenheim included the 1981 exhibition of his holdings, acquired and protected the richest collection of its kind at a time when almost no institutional attention was being paid to this revolutionary chapter in the history of art.

The exhibition represents the most complex logistical effort ever undertaken by the Guggenheim, involving more people and institutions around the world than any other of the museum’s projects and requiring sponsorship from the start. It can often be simply a formality to acknowledge a sponsor. In this case, Lufthansa German Airlines cannot be identified merely as an exhibition sponsor with a natural regard for culture, although it is one of the most active corporate supporters of cultural events throughout the United States, Europe, and Russia. Rather, Lufthansa served as a collaborator—bringing people together, carrying precious information as well as people and art, and providing assistance (including translation and communications) in negotiations. Jurgen Weber, President and CEO, is dedicated, as was his predecessor, Heinz Ruhnau, to a world linked by the high technology of air travel as well as by the essential fabric of cultural communication. That Lufthansa’s dedication to culture is deeply rooted in its mission to connect people is no more evident than in the work of Nicolas Iljine, Director of Public Affairs, who was present with Dr. Heinrich Klotz, Director of the Zentrum fur Kunst und Medientechnologie, at the inception of the project. Through his equal dedication to people, culture, and business, Nic Iljine was a source of expertise and inspiration throughout a long and complex process.

In sum, it might be stated that the urgency and importance of this unique project is evidenced by the extraordinary hard work, commitment, and faith it inspired in its participants. Utopia is not at hand, but the art of the Russian and Soviet avant-garde in this exhibition may plainly demonstrate some of its essential components—that a blueprint for the future may be more likely found on the margins of our consciousness than at its center; that it may require the invention of a new starting point (the zero form of Malevich’s Black Square), the progressive involvement of every stratum of society, and the engagement with a diversity of changing aesthetics that becomes the foundation of a practical system of human communication in the midst of a changing world.

—Thomas Krens, Director

Michael Govan, Deputy Director

Preface

The Russian avant-garde is a chapter of art history which demands a higher level of knowledge. While many collections around the world house Russian masterpieces from this period and many worthy publications and important exhibitions have presented the originality of Russian culture in the years before and after the October Revolution, these collections and surveys have only highlighted the many nuances and riches of this culture that remain to be explored. Moreover, most of the exhibitions focusing on the Russian avant-garde have discussed the works of art within the narrow framework of the Revolution. As a result, artistic processes have often been neglected in favor of the political and social implications of the works.

The history and role of Russian avant-garde art are far more complex. These artists, despite being intimately bound by the social and political situation of their country, were absorbed as never before by questions of pure aesthetics. The world of the European Modernists—a world which had opened to Russian artists for the first time and whose development they followed with lively interest—combined with their own artistic, literary, and philosophical heritage to create a unique context for innovative creative experiments.

At the turn of the century, an artistic vocabulary capable of describing all possible experiences seemed unquestionably in place. In Russia, the newly defined world order and life-style required new forms of expression. While the artists central to the vanguard movement—Mikhail Larionov, Natal'ia Goncharova, Vasilii Kandinskii, Kazimir Malevich, Pavel Filonov, and others—did not come fully into their own with the Revolution, the events of 1917 focused their maturation. In the diversity of artistic movements in Russia from 1910 to 1920, two principal trends can be clearly discerned and differentiated. One trend describes the emotional-intuitive penetration of the material world, and the other tries to understand matters through a rational-Constructivist analysis. As a result, the initial working title for the present exhibition was Construction and Intuition. Although this title was eventually changed, the two themes helped to define the concept at the heart of the exhibition: the tension within the Russian avant-garde between rational and irrational experiences and representations of the world.

In a political sense, this exhibition comes perhaps too late. Since the early 1980s, the idea of romantic underpinnings to the Revolution has lost popularity. Yet the artistic might of this era, with its gathering of creative energies and investigations, has continued to hold its ground against more short-lived political ideologies and economies. It is therefore that much more important for the public to be able to see for the first time the breadth of Russian avant-garde art without a background of political fervor—to see it in peace and to be able to measure fully its place in the development of art in our world.

Our heartfelt thanks to our partners in this project, Thomas Krens, Director of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York and the Peggy Guggenheim Collection in Venice; Michael Govan, Deputy Director of the Guggenheim Museum; and Christoph Vitali, Director of the Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt.

American, German, and Russian experts have contributed to extensive research and to developing the complex thematic structure of the exhibition. This was not only a fruitful collaboration for the exhibition but also a personal accomplishment for each individual involved.

Equal thanks are due to the sponsor of the exhibition, Lufthansa German Airlines; to Nicolas Iljine, Director of Public Affairs at Lufthansa, who followed the nearly four years of preparations with great sympathy, involvement, and patience; to the former Soviet Ministry of Culture and its staff; and to the Vuchetich All-Union Artistic Production Association (VUART), with Valentin Rivkind at the helm.

Finally, we are tremendously grateful to all museums and private lenders for the very generous gift of their works as loans to the exhibition.

—Vladimir Gusev, Director

Evgeniia Petrova, Deputy Director

State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg

Iurii Korolev, Director

State Tret'iakov Gallery, Moscow

Contents

Prefaces

Thomas Krens, Michael Govan X

Vladimir Gusev, Evgeniia Petrova, lurii Korolev XIII

Jurgen Weber XIV

The Politics of the Avant-Garde. Paul Wood 1

The Artisan and the Prophet: Marginal Notes on Two Artistic Careers. Vasilii Rakitin 25

The Critical Reception of the 0.10 Exhibition: Malevich and Benua. Jane A. Sharp 38

Unovis: Epicenter of a New World. Aleksandra Shatskikh 53

COLOR PLATES 1—318

A Brief History of Obmokhu. Aleksandra Shatskikh 257

The Transition to Constructivism. Christina Lodder 266

The Place of Vkhutemas in the Russian Avant-Garde. Natal'ia Adaskina 282

What Is Linearism? Aleksandr Lavrent'ev 294

The Constructivists: Modernism on the Way to Modernization. Hubertus Gassner 298

The Third Path to Non-Objectivity. Evgenii Kovtun 320

COLOR PLATES 319—482

The Poetry of Science: Projectionism and Electroorganism. Irina Lebedeva 441

Terms of Transition: The First Discussional Exhibition and the Society of Easel Painters. Charlotte Douglas 450

The Russian Presence in the 1924 Venice Biennale. Vivian Endicott Barnett 466

The Creation of the Museum of Painterly Culture. Svetlana Dzhafarova 474

Fragmentation versus Totality: The Politics of (De)framing. Margarita Tupitsyn 482

COLOR PLATES 483—733

The Art of the Soviet Book, 1922—32. Susan Compton 609

Soviet Porcelain of the 1920s: Propaganda Tool. Nina Lobanov-Rostovsky 622

Russian Fabric Design, 1928—32. Charlotte Douglas 634

How Meierkhol'd Never Worked with Tatlin, and What Happened as a Result. Elena Rakitin 649

Nonarchitects in Architecture. Anatolii Strigalev 665

Mediating Creativity and Politics: Sixty Years of Architectural Competitions in Russia. Catherine Cooke 680

Index of Artists and Works 716

Sample pages

Download link (pdf, yandexdisk; 440 MB)

17 сентября 2017, 18:11

0 комментариев

|

Партнёры

|

Комментарии

Добавить комментарий