|

|

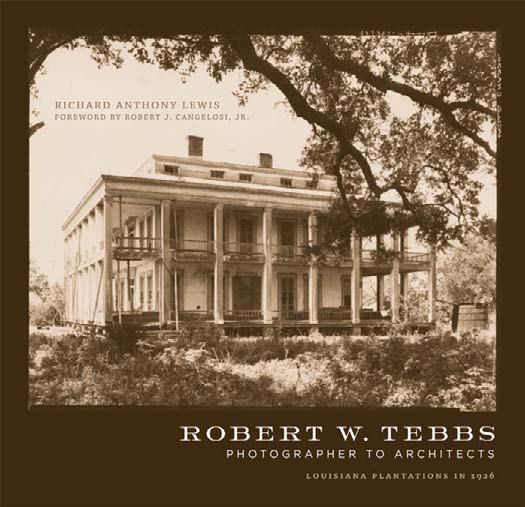

Lewis R. A. Robert W. Tebbs, Photographer to Architects: Louisiana Plantations in 1926. — Baton Rouge, Louisiana, 2011  Robert W. Tebbs, Photographer to Architects: Louisiana Plantations in 1926 / Richard Anthony Lewis ; foreword by Robert J. Cangelosi, Jr. — Baton Rouge, Louisiana : Louisiana State University Press, 2011. — XVI, 151 p., ill.

One of the finest architectural photographers in America, Robert W. Tebbs produced the first photographic survey of Louisiana’s plantations in 1926. From those images, now housed in the Louisiana State Museum, and not widely available until now, 119 plates showcasing fifty-two homes are featured here. Richard Anthony Lewis explores Tebbs’s life and career, situating his work along the line of plantation imagery from nineteenth-century woodcuts and paintings to later twentieth-century photographs by John Clarence Laughlin, among others. Providing the family lineage and construction history of each home, Lewis discusses photographic techniques Tebbs used in his alternating panoramic and detail views. A precise documentarian, Tebbs also reveals a poetic sensibility in the plantation photos. His frequent emphasis on aspects of decay, neglect, incompleteness, and loss lends a wistful aura to many of the images—an effect compounded by the fact that many of the homes no longer exist. This noticeable vacillation between objectivity and sentiment, Lewis shows, suggests unfamiliarity and even discomfort with the legacy of slavery. Poised on the brink of social and political reforms, Louisiana in the mid-1920s had made significant strides away from the slave-based agricultural economy that the plantation house often symbolized. Tebbs’s Louisiana plantation photographs capture a literal and cultural past, reflecting a burgeoning national awareness of historic preservation and presenting plantations to us anew. Select plantations included: Ashland/Belle Helene, Avery Island, Belle Chasse, Belmont, Butler-Greenwood, L’Hermitage, Oak Alley, Parlange, René Beauregard House, Rosedown, Seven Oaks, Shadows-on-the-Teche, The Shades, and Waverly.

FOREWORD

It was 1926, and New Orleans jazz was all the rage. Louis Armstrong had his Hot Five, Jelly Roll Morton had the Red Hot Peppers, and King Oliver, the Creole Jazz Band. Women called flappers sported calf-length dresses and short “Eton crop” hairstyles. Prohibition was in effect, and in New Orleans, the Absinthe House was closed by court injunction for violation of the Volstead Act. Louisiana governor Henry Fuqua died in office on October 11 and was succeeded by Lieutenant Governor Oramel H. Simpson. During his tenure, Fuqua, who had defeated Huey Pierce Long for the state’s top office, worked to suppress activities of the Ku Klux Klan by outlawing masking, and approved the contract for the first bridge across Lake Pontchartrain.

In 1926, the present campus of Louisiana State University in Baton Rouge was dedicated; Lake Charles completed a waterway establishing it as a gulf port; Louisiana’s first public airport was built in Mansfield; and the Pelicans, the state’s minor league baseball team, won the Southern Association’s pennant.

New Orleans mayor Martin Behrman died in office on January 12, 1926, after serving seventeen years; Tulane Stadium, later known as Sugar Bowl Stadium, was built Uptown; the Double Dealer, an influential literary magazine in its sixth and final year of publication, offered a national medium for southern writers; the New Orleans Arts and Crafts Club provided local artists a venue for their work; and the Louisiana chapter of the American Institute of Architects (AIA) began work on special preservation zoning for the Vieux Carré.

The weather in 1926 was not the best. In August, persistent heavy rains began to fall across the Mississippi Valley, including Louisiana, and continued until spring, culminating in the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927 that left 300,000 people homeless in Louisiana alone. In August 1926, a hurricane with 120-mile-per-hour winds struck southeast Louisiana, near Houma. New Orleans, Baton Rouge, Lutcher, Garyville, Burnside, Geismar, Hammond, and Ponchatoula all sustained heavy damage following the fifteen-foot tidal surge that smashed into Terrebonne Parish, causing twenty-five deaths and millions of dollars in property damage as far north as Shreveport. The next month, the Great Miami Hurricane hit Louisiana, having initially made landfall in Miami on September 18, killing 372. The category 4 storm crossed Florida, entered the Gulf of Mexico, stalled below Pensacola, and then ravaged Mississippi and Louisiana on September 21.

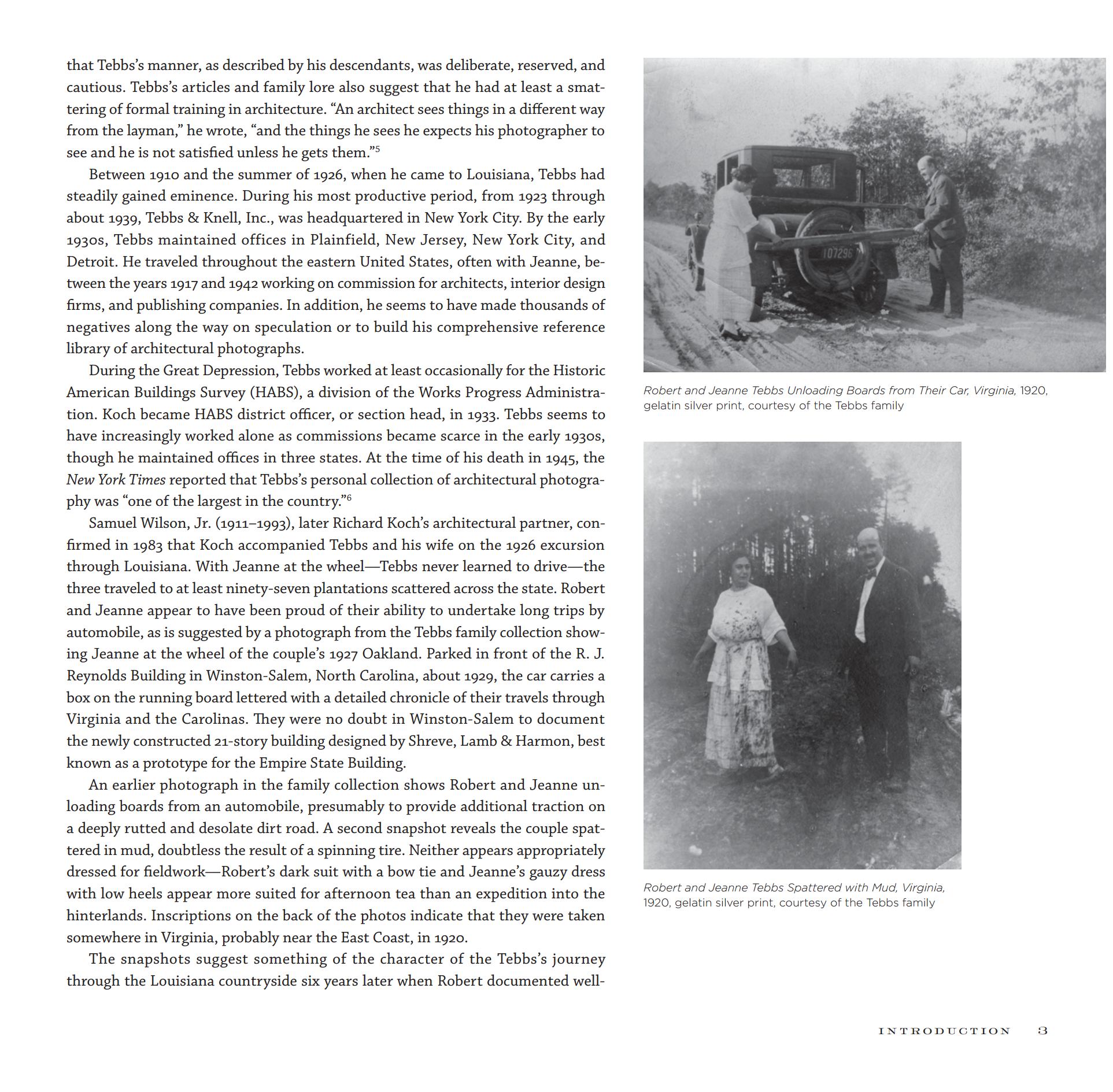

Also in 1926, photographer Robert Tebbs made a tour of southeast Louisiana, accompanied by his wife Jeanne and architect Richard Koch, documenting its architectural history. At fifty-one, Tebbs was established in his photography career, while Koch, at age thirty-seven, was only in his tenth year as partner in his architectural firm of Armstrong and Koch. As early as 1924, Koch had commissioned Tebbs to photograph his firm’s projects in Natchez, Mississippi, and the following year, in both New Orleans and Natchez. These excursions were undertaken in connection with the ill-fated Octagon Library project that was to have been published by the Press of the American Institute of Architects. With Koch guiding the Tebbses, the three toured and documented the eighteenth-and nineteenth-century rural homes of Louisiana, recording, even for then, a bygone era. Tebbs focused on the architecture and architectural details, apparently with little interest in laborers, animals, and crops. His photographs record the 1920s appearance of historic houses now lost, as well as those that survive.

The photographic documentation by Tebbs of the historic architecture of southeast Louisiana was part of an ongoing national movement to record America’s architectural heritage—in particular Federal and Greek Revival buildings that are often erroneously called Colonial—through photographs and measured drawings. The movement had inspired an architectural revival that gained speed after the country’s centennial celebration in 1876. As early as 1869, at the AIA national convention, Richard Upjohn suggested that architects “make careful studies of some of the old houses yet remaining” in order to “gain a valuable lesson.”1 For the centennial celebration in Philadelphia, architect Donald Mitchell suggested that Louisiana reproduce for its state exhibition building an old New Orleans-style structure with a wraparound gallery such as the one he had illustrated in his 1867 book Rural Studies. Except for isolated regional efforts, the interest in America’s architecture was centered on the Atlantic seaboard, especially New England; however, other areas of the country quickly realized that their heritage was different.

____________

1Proclamation of the Third Annual Convention of the AIA (November 1869): 47–51.

An 1881 AIA national committee concluded that Colonial architecture should influence, not govern, contemporary designs, and that seems to have been the case, for most revivals took a Mannerist approach. During the 1880s and 1890s, practically every architectural magazine carried well-illustrated articles on “Colonial architecture,” often with measured drawings. In Louisiana, as elsewhere, the initial form of the Colonial Revival ignored its heritage and looked to the East Coast for inspiration. In 1888, the New Orleans Daily Picayune reported that “Old Colonial” architecture had its admirers in New Orleans, and was influencing designs of large residences.2

____________

2 “Hammer and Trowel,” New Orleans Daily Picayune, September 1, 1888.

As more and more photographs and drawings appeared in periodicals and books, the revival movement became more academically correct. The six volumes of The Georgian Period, edited by William Rotch Ware and initially published in 1898, contained photographs and measured drawings of American architecture, including in the 1923 edition pictures of four Louisiana plantations and three New Orleans buildings. The White Pine Series of Architectural Monographs, published between 1915 and 1940, also contained photographs and measured drawings of historic buildings. Both sets of publications were in the libraries of many local architects, including that of Richard Koch. The national magazine American Architect and Building News in 1896 and 1897 featured plates of New Orleans buildings, and the New Orleans-based Architectural Art and Its Allies in 1895 illustrated many local historic structures. The editors of that periodical argued in 1909 for indigenously inspired houses for Louisiana, patterned after the state’s galleried plantation houses.

The Greek Revival style was erroneously thought to be Colonial at the beginning of the twentieth century. The New Orleans architectural magazine Building Review commented in 1915 on the “obvious dignity of the type we call ‘Southern Colonial,’ the tall colonnaded portico and severe classicism.” The Louisiana chapter of the AIA founded its Committee on Preservation of Historic Monuments in 1915, and established a budget of “$25 at a time for the measuring or photography of old, historic buildings liable to be destroyed.”3

____________

3 “Sincerity in Architecture,” Building Review (January 23,1915): 21; “Activities and Accomplishments of the Louisiana Chapter AIA during the Past Year,” Building Review (January 30, 1915): 8.

Building News in 1916 reported that Ellsworth Woodward and John Kendall had photographically documented the ironwork of New Orleans and exhibited their work at Newcomb College with hopes of publishing it. That same year, local architect Nathaniel C. Curtis announced in the national AIA journal that the Louisiana chapter, in conjunction with the architecture department of Tulane University, was to record the state’s historic buildings through a series of measured drawings and photographs, accompanied by text on each structure’s history and architecture.

This focus on the past was leading to a greater appreciation of Louisiana architecture. Morgan Hite, another local architect, wrote in Building Review in 1918 that he hoped New Orleans would “create, in time, an architecture that will be of itself, for itself, outstanding and unique in the history of such things.” The following year, Nathaniel Curtis reported in Building Review on the growing influence of Louisiana’s architecture outside of the state: “I am reminded of the Institute Convention [AIA] of 1913 held in New Orleans and every once in a while I come across a building illustrated somewhere which makes me believe that some of these visitors at that time have known how to make use of their impressions of what they saw in the ‘Vieux Carre’ or ‘Garden District.’ Such, for example, as the house illustrated in the Architectural Forum last July designed by Delano and Aldrich for a man in Woodbury, Long Island.”4 Indeed, Samuel S. Labouisse, Richard Koch, and Hays Town were prominent among local architects developing a revival of Louisiana architecture. By the time Tebbs began recording Louisiana plantations in 1926, there was an established tradition of local architecture.

____________

4 Morgan Hite, “The Influence of Wood Architecture,” Building Review (June 1918): 24; “Influence of New Orleans Architecture Is Spreading,” Building Review (February 1919): 9.

The designers of most of the Louisiana rural residences photographed by Tebbs in 1926 go unrecorded; for some, there is speculation, but only five can be attributed with any certainty. Henry Howard designed Wood-lawn, Madewood, and Belle Grove. Known for his Greek Revival and Italianate designs, Howard was born in Cork, Ireland, immigrated to New York at age sixteen, and arrived in New Orleans in 1837, during the height of a yellow fever epidemic. He studied architecture with James Dakin and Henry Molhausen, and after the construction of Madewood on Bayou Lafourche for Thomas Pugh, Howard opened his office on Exchange Place in New Orleans. Gilbert Joseph Pilié, designer of the iconoclastic Oak Alley, was a native of Santo Domingo who fled to New Orleans during the slave revolts. A civil engineer and architect by profession, Pilié served as city engineer from 1818 to 1844. Little is known of James Hammond Coulter, designer of Greenwood, the only other documented house.

The fifty-two houses illustrated in this book are located in eighteen southeast Louisiana parishes, with the most in West Feliciana Parish. The residences photographed are generally of two types, the regionally appropriate Louisiana Creole type and the Greek Revival. As a rule, eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century Louisiana Creole (French Colonial) plantation houses have hall-less plans, with rooms arranged en suite, casement doors and windows, boxed mantels projecting into the rooms, and external stairs. Galleries are a distinctive feature, extolled by traveler Claude César Robin in Voyage to Louisiana, 1803–1805: “These wide galleries have several advantages. First they prevent the sun’s rays from striking the walls of the house and thus to keep them cool. Also, they form a convenient and pleasant spot upon which to promenade during the day ... one can eat or entertain there, and very often during the hot summer nights one sleeps there.”5

____________

5 C. C. Robin, Voyage to Louisiana, 1803–1805, trans. Stuart O. Landry, Jr. (New Orleans: Pelican, 1966), 122.

The Greek Revival style, which arrived in Louisiana with the influx of easterners during the 1830s, promoted Classical, preferably Greek details, such as dentils, crossetted frames, egg-and-dart, bead and reed, triglyph and mutules, central halls, low-pitched or hidden roof, and a monumental scale. The style was popularized by The Antiquities of Athens, by James Stuart and Nicholas Revett, published between 1762 and 1816 and republished in 1830; and by The Beauties of Modern Architecture, by Minard Lafever (1835), for which James Gallier, Sr., and James Dakin provided many of the plates. East Coast architects, particularly from New York, brought the style to Louisiana. William Strickland, who started the vogue with his Second Bank of the United States in Philadelphia, designed the United States Mint (1835–1838) in New Orleans in the Greek Revival style.

While other photographers, such as George François Mugnier and Olide Schexnayder, documented rural life in Louisiana, Tebbs was one of the first to make an in-depth study of the architecture. Richard Koch almost certainly selected the sites to visit. He would himself photograph many of the same houses between 1933 and 1941 while serving as director of the Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) in Louisiana. Koch “gained much knowledge of photography” from Tebbs during the trips, according to his later partner, Samuel Wilson, Jr.6

____________

6 Samuel Wilson, Jr., “The Survey of Louisiana in the 1930s,” in Historic America: Buildings, Structures, and Sites (Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress, 1983).

For the 1938 AIA national convention in New Orleans, the architectural journal Pencil Points published twelve photographs by Tebbs of historic Louisiana plantation houses, accompanied by four sheets of HABS drawings of Ormond Plantation, the documentation of which had been overseen by Koch. Also featured were photographs of several Vieux Carré buildings taken by Richard Koch, and two architectural projects of his firm, Le Petit Théâtre and 730 Esplanade Avenue. The special issue also contained a foldout Map of the State of Louisiana, drawn by Alvyk Boyd Cruise, with images of seventeen historic buildings in the border, most of which had been photographed by Tebbs in 1926.

As district director of HABS during the 1930s, Koch oversaw the measuring of many of the houses photographed by Tebbs that were later renovated by his architectural firm, including Oak Alley, Shadows-on-the-Teche, Evergreen, the René Beauregard House, Elmwood, Hurst-Stauffer House, and Rosedown. Koch’s approach to preservation architecture was to extend the useful life of the building through renovation and adaptive reuse rather than restoration, as his successor firms would later do for San Francisco Plantation, in Garyville, Louisiana, and the Pitot House and the Cabildo in New Orleans.

As president of the Friends of the Cabildo and Koch & Wilson Architects, I am honored to pen this foreword.

Robert J. Cangelosi, Jr., AIA

PRESIDENT, KOCH & WILSON, APC

CONTENTS

FOREWORD, by Robert J. Cangelosi, Jr. ix

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS xiii

INTRODUCTION: Representing Louisiana Plantations, 1926 1

PHOTOGRAPHS OF LOUISIANA PLANTATION HOUSES

Elmwood Plantation 29

Parlange Plantation 31

Voisin Plantation 33

Homeland Plantation 35

Ormond Plantation 37

Labatut Plantation 39

Whitney Plantation 41

Evergreen Plantation 43

The Cottage Plantation 45

Houmas House/Burnside Plantation 47

Oakley Plantation 49

Three Oaks Plantation 51

Glendale Plantation 53

The Shades 55

Old Hickory Plantation 57

Butler-Greenwood Plantation 59

Hickory Hill Plantation 61

L’Hermitage (Hermitage Plantation) 63

Asphodel Plantation 65

Pleasant View Plantation 67

Waverly Plantation 69

Ellerslie Plantation 71

Live Oak (or Live Oaks) Plantation 73

Hurst-Stauffer House 75

Greenwood Plantation 77

Belle Chasse Plantation 79

Magnolia Ridge Plantation 81

Calumet Plantation 83

Chretien Point Plantation 85

Shadows-on-the-Teche 87

Rene Beauregard House 89

Wakefield Plantation 91

Rosedown Plantation 93

Welham Plantation 95

Seven Oaks Plantation 97

Woodlawn Plantation 99

Oak Alley Plantation 101

Marston House 103

Brame House 105

Rienzi Plantation 107

Ashland/Belle Helene Plantation 109

Madewood Plantation 111

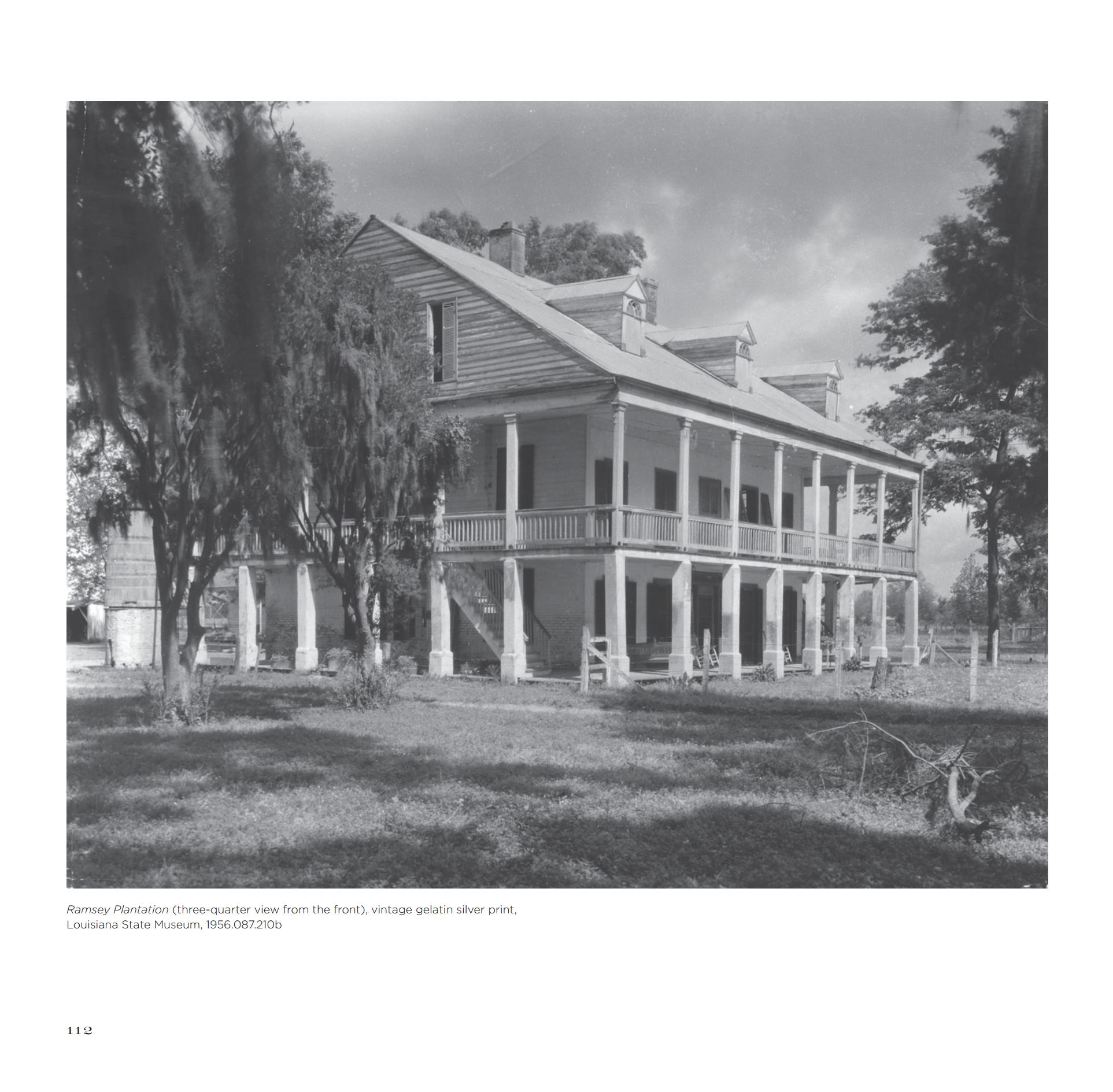

Ramsey Plantation 113

Bagatelle Plantation 115

Uncle Sam Plantation 117

Belle Alliance Plantation 119

Mount Airy Plantation 121

Belmont Plantation 123

Angelina Plantation 125

Goodwood Plantation 127

Belle Grove Plantation 129

Avery Island Plantation 131

APPENDIX: The Robert W. Tebbs Collection at the Louisiana State Museum 133

NOTES 135

SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY 141

INDEX 145

Sample pages

Download link (pdf, yandexdisk; 81,6 MB)

Все авторские права на данный материал сохраняются за правообладателем. Электронная версия публикуется исключительно для использования в информационных, научных, учебных или культурных целях. Любое коммерческое использование запрещено. В случае возникновения вопросов в сфере авторских прав пишите по адресу 42@tehne.com.

17 декабря 2019, 10:44

0 комментариев

|

Партнёры

|

Комментарии

Добавить комментарий