|

|

Marco De Michelis. Aldo Rossi and Autonomous Architecture

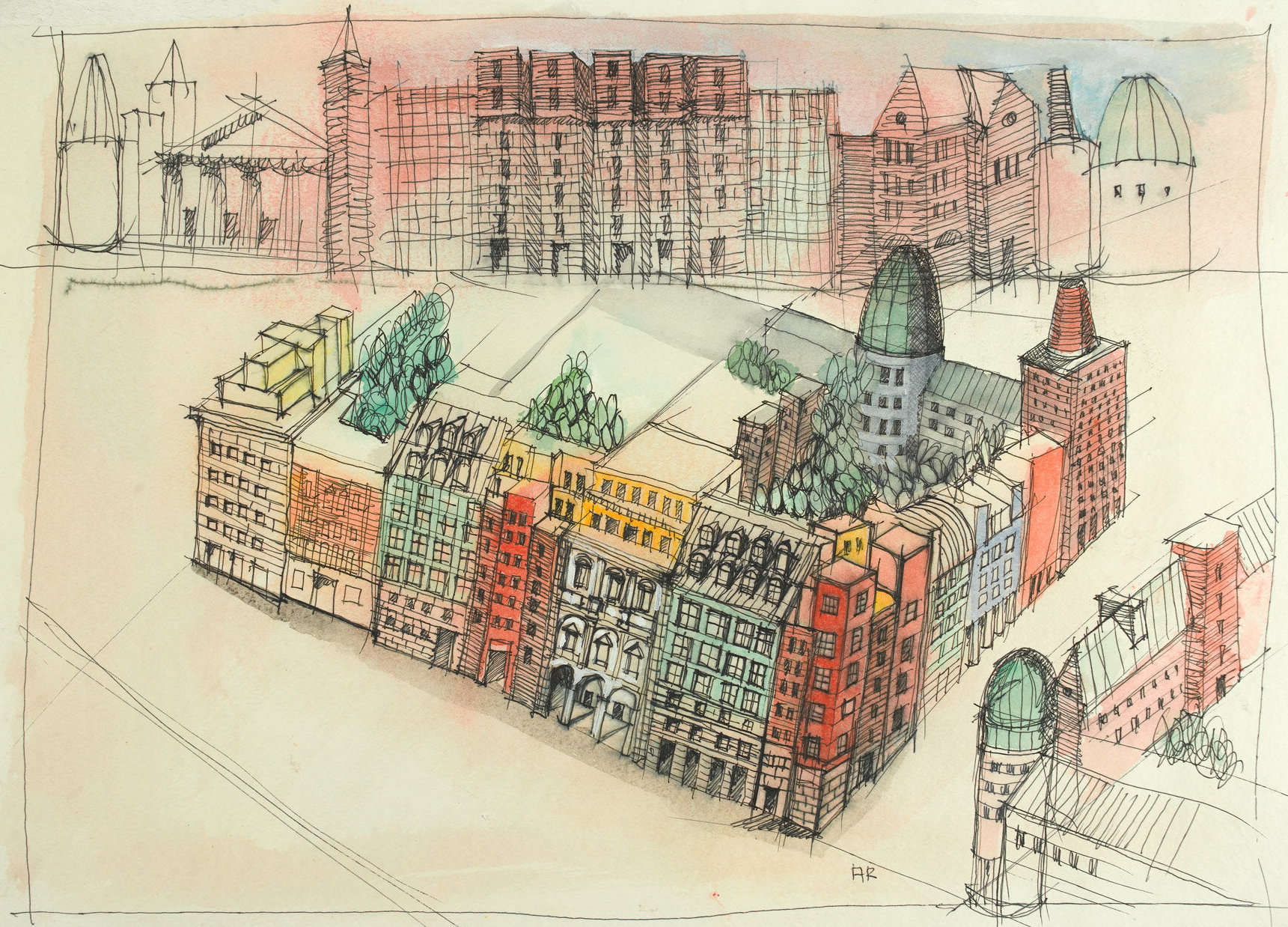

©Eredi Aldo Rossi, courtesy Fondazione Aldo Rossi | Study for the block in Schützenstrasse/Berlin, 1993, Aquarell and ink on paper, 49.6 × 70.5 cm, private collection

ALDO ROSSI AND AUTONOMOUS ARCHITECTUREMarco De Michelis

The Howard Gilman Archive of Visionary Architectural Drawings offers an extraordinary opportunity to consider the theoretical underpinnings of the architectural culture of the 1960s and 1970s. During this singular period, paper architecture played an important role in the articulation of a general disillusionment with the modern movement. An analogous expression of these concerns was also to be found among the works of writers and historians, some of them architects as well, which sought to analyze modernism's failure to fulfill its utopian promise and to remediate its misguided route. In addition, all of this took place against a backdrop of the widespread student protests and civil disobedience of the time.

The Gilman collection is unique in encompassing a variety of architectural responses to these issues: utopian, radical, monumental, Pop, technological, metaphysical, poetic, philosophical, or traditionally nostalgic; taken together they articulate the key movements of a time of artistic and social ferment that came to define the postwar world in terms of what were known as the megastructure movement and, later, postmodernism. This collection includes such definitive works as the visionary representations of the Plug-In City by Peter Cook of Archigram (pages 50–53); Yona Friedman's Spatial City (pages 40–41, 43); and works by the Austrian Max Peintner and the Italian Gaetano Pesce, which were drawn with the naive communicative power of science-fiction comics (pages 108–109, 123, 131–133). All played an important role in moving architecture beyond modernism, as did the metaphysical landscapes sketched by Aldo Rossi, Léon Krier, and Massimo Scolari (pages 103–105, 110, 118, 124, 125); the remarkable bird's-eye views from Superstudio (pages 73–77); and Rem Koolhaas's and Elias Zenghelis's colorful axonometrics of New York (page 144).

The architectural culture during this critical period in the intellectual and creative history of the twentieth century was defined largely by architects, philosophers, and historians, whose diverse ideas were connected only by a common determination to alter the obsolete tenets of modernist practice and to reevaluate architecture in terms of the new imperatives of the postwar world. Among the most influential in helping to define the future of postmodernist practice, were the ideas of the Italian architect Aldo Rossi, whose 1966 book The Architecture of the City patiently built the foundations for a detached theory of architectural autonomy which had a crucial influence both in Europe and America,1 Rossi's moving manifesto was written at a time when his theories could only be tested on a small number of his projects, such as the designs for a competition for the Teatro Paganini in Parma (1964) and the neighborhood of San Rocco in Monza, near Milan (1966), and even fewer built works, such as the piazza in Segrate outside Milan, a commission he owed to the young Milanese architect Guido Canella. It was also published in the same year as an equally influential book appeared in America, Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture by Robert Venturi, that attacked the same issues from a different angle.2 Venturi's book was also an attempt to shape an original historical context lor contemporary architecture. In terms of the ideas of autonomy espoused by Rossi and others in Europe, the most important aspect of Venturi's book was its related aim of reestablishing in architecture an intrinsic complexity that would be detached from other disciplines, such as science, technology, and the humanities and social sciences, which he felt had blurred the boundaries between themselves and modern architecture. Venturi wrote: "I make no special attempt to relate architecture to other things. ... I try to talk about architecture rather than around it. ... The architect's ever diminishing power and his growing ineffectualness in shaping the whole environment can perhaps be reversed, ironically by narrowing his concerns and concentrating on his own job."3

____________

1. Aldo Rossi, L’Architettura della città (Padua: Marsilio Editori, 1966); revised edition, in English: The Architecture of the City, Oppositions Books (Cambridge, Mass., and London: MIT Press, 1982).

2. Robert Venturi, Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture (New York: The Museum of Modem Art, 1966); second edition, 1977.

3. Ibid., second edition: 14.

Rossi's book opens with the now famous declaration of a fundamental unity of identity between the city and architecture, and proposes a theory of urban artifacts characterized by "the identification of the city itself as an artifact and its division into individual buildings and dwelling areas."4 For Rossi, "monuments, signs of collective will as expressed through the principles of architecture,"5 are the fixed points in an urban dynamic, and constitute one of the principal elements in the history of culture. His peremptory affirmation of the city's architectural character implies an autonomy through which architecture itself is empowered to construct a new "urban science," and stands as one of the constituent elements of the concept of autonomous architecture.

____________

4. Rossi, Architecture of the City, revised edition, in English: 21–22 (pages cited hereafter refer to this edition).

5. Ibid.: 22.

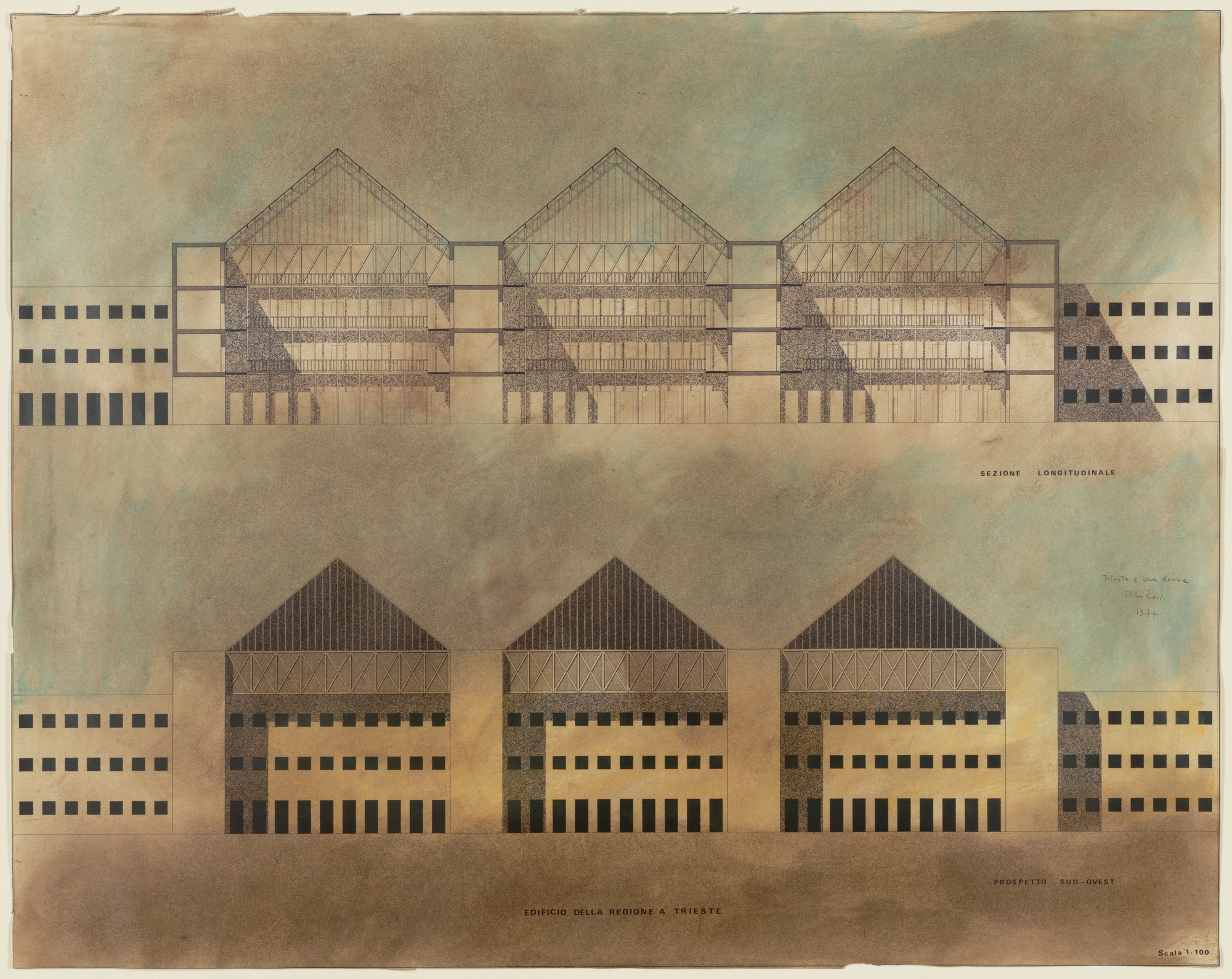

Rossi's sources for his discussion of the city are highly varied. They range from classical linguistics and tools for interpreting processes of modification and permanence that can be transferred from language to the description and history of urban phenomena, by such thinkers as Ferdinand de Saussure, to disciplines such as structural anthropology, urban geography, sociology, economic policy, the tradition of modern town planning, and the vast patrimony of architectural theory. Backed by his use of these references and disciplines, Rossi tackled the problem of describing the architecture of the city, proposing it as the assimilation of large artifacts, the feats of engineering and public architecture (figure 1). Considering the city to be much like a collective work of art, Rossi wrote: "We should initially state that there is something in the nature of urban artifacts that renders them very similar—and not only metaphorically—to a work of art."6 Rossi had retrieved the notion of a collective work of art from the French anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss, as born in unconscious life, between nature and artifice, "an object of nature and a subject of culture."7 From the great French sociologist Maurice Halbwachs, he adopted the belief "that imagination and collective memory are the typical characteristics of urban artifacts."8 The relationship between the city and its inhabitants, how people orient themselves and move about within it, and form their sense of space, further enriched the issue of collective belonging and the awareness of the city as an artistic whole, allowing Rossi to formulate his conception of architecture as "a human thing,"9 that shapes reality and adapts material according to an aesthetic conception.

____________

6. Ibid.: 32.

7. Ibid.: 33.

8. Ibid.

9. Ibid.: 35.

In the work of Jean-Nicolas-Louis Durand, Antoine Chrysostôme Quatremère de Quincy, and Eugène-Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc, Rossi found the historical foundation for a theory of types, as "permanent and complex, a logical principle that is prior to form and that constitutes it."10 He added his own particular emphasis to an essentially meta-historical—even metaphysical—typology as "the very idea of architecture, that which is closest to its essence."11 It was through the notion of type that the historicity of architecture took shape in its formal inventions, its constructive innovations, its capacity to respond to different needs and functions, and its many variations of design solutions.

____________

10. Ibid.: 40.

11. Ibid.: 41.

From this point of view, typology, defined by Rossi as "the study of types of elements that cannot be further reduced,"12 constituted a formidable tool for his investigation of the city's fixed characteristics, according to the model proposed in the early twentieth century by Marcel Poète and Pierre Lavedan and their research on the generation of the urban plan. They described this as an element that simultaneously constituted the city's permanent character and a representation of its overall wholeness. For Rossi, this last point was the most important feature of their research, the idea that: "Cities tend to remain on their axes of development, maintaining the position of their original layout and growing according to the direction and the meaning of their older artifacts."13

____________

12. Ibid.

13. Ibid.: 59.

Rossi's approach had many highly important consequences. His city as total architecture became describable and interpretable both in its wholeness and in the parts of which it was composed. The primary elements could he recognized in those monuments in which the very essence of the urban artifact and the forms of its surrounding environment are condensed. The characteristics of its growth, its various social, economic, and political components, could finally be led back to a sole principle and a single practice.

These considerations of the young Rossi were not the result of a solitary effort. There was in the background, from the very beginning, Saverio Muratori's research on the urban structure of Venice, although there is no specific trace of it in The Architecture of the City. Of particular interest to Rossi was Muratori's attempt to replicate the city's morphological structures in his project for the residential neighborhood of San Giuliano in Venice in 1959,14 but it provided no basis for Rossi's own contemporary design choices.

____________

14. Saverio Muratori, Studi per una operante storio urbano di Venezia (Rome: Istituto Poligrafico dello Stato, 1963). See also: Giorgio Pigafetta, Saverio Muratori Architetto (Venice: Marsilio Editori, 1990).

Figure 1. Aldo Rossi and Gianni Braghieri, with M. Bosshard, Regional Administrative Center, Trieste, Italy, Project 1974. Competition entry: elevation and section, rubbed ink and pastel on whiteprint, 28½ × 36" (72.4 × 91.4 cm). The Museum of Modem Art, New York. Philip Johnson Fund

Also in Venice, Carlo Aymonino had been working at the Istituto Universitario di Architettura exploring the relationship between urban morphology and building typology with the aim of establishing "a method of analysis that, by placing different processes in relationship with each other, also allowed one to forecast urban issues."15 In the research, morphology and typology served to describe the complexity of the city's settlement process: the relationships between built space and the system of public spaces, between the ways in which it was actually used and the designated uses and building forms, and including a penetrating analysis of the peculiar characteristics of the architecture of housing and large public structures. It was precisely the challenge of a morphological coherence in the historical city, able to resist transformation and tampering by history, that provided the premise of a design strategy that professed to measure itself on major issues of urban architecture of the time, such as the reorganization of the residential suburbs of Milan in Aymonino's and Rossi's project for Gallaratese, the new civic centers in the projects for Perugia or Pesaro, and the patient rehabilitation of the historical tissue of the ancient city, such as Venice, using morphological structures coherent with those of the past.

____________

15. Carlo Aymonino, Origini e sviluppo della città moderna (Padua: Marsilio Editori, 1965): 54.

In 1965, the Novissime project, done by a group coordinated by Giuseppe Samonà, the director of the Istituto Universitario di Architettura in Venice, represented an extreme prototype of this attitude. It proposed to actually remove any built elements that were found to be inconsistent with the original Venetian morphological structure, in particular, by thinning and emptying out certain areas in Venice's eastern and western appendixes.

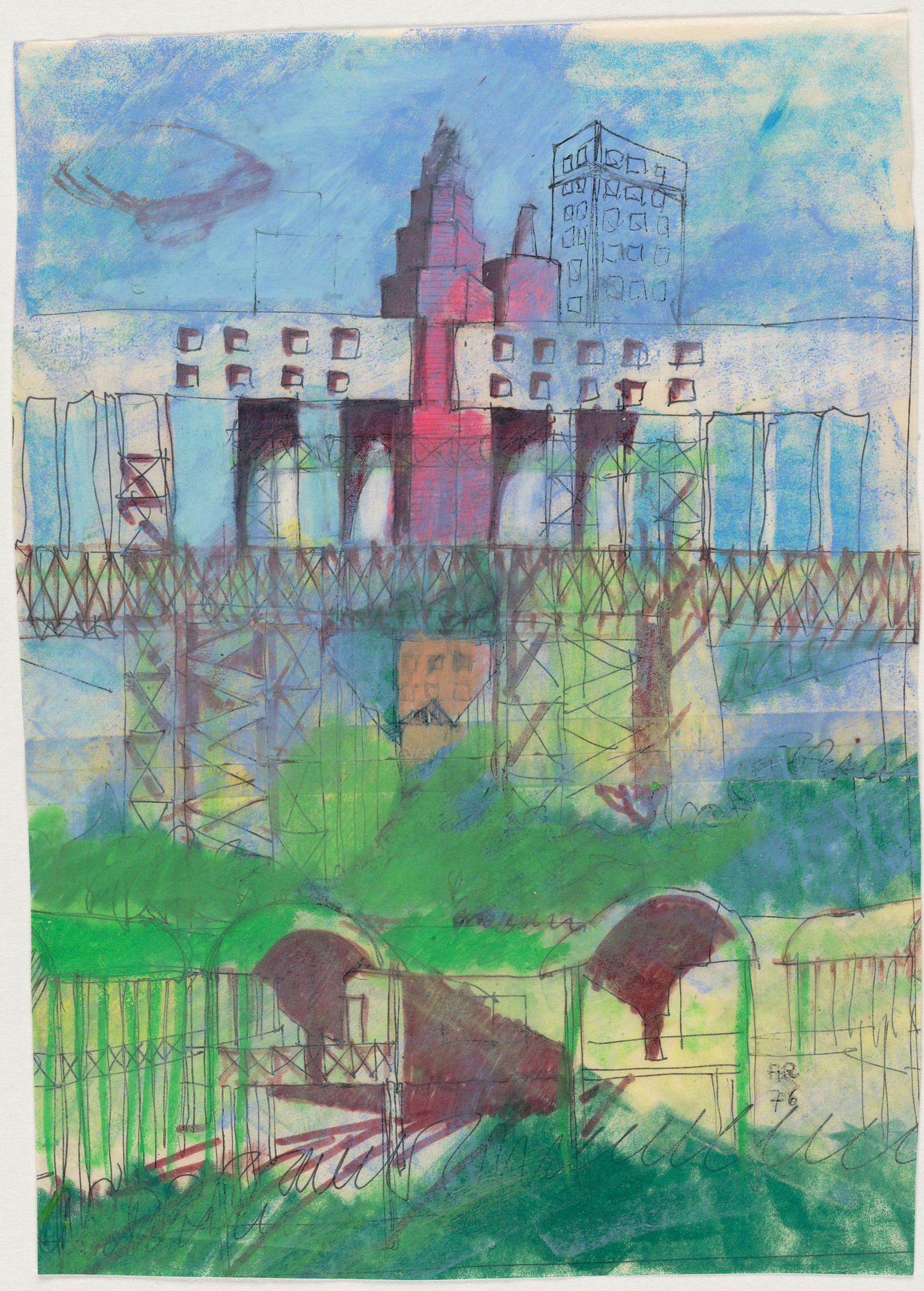

In 1978, an international seminar was held in Venice, during which ten architects (Raimund Abraham, Carlo Aymonino, Peter Eisenman, John Hejduk, Rafael Moneo, Bernhard Hoesli, Valeriano Pastor, Gian Ugo Polesello, Aldo Rossi, and Luciano Semerani) put themselves to the test redesigning a vast area of the Cannaregio, a neighborhood located between the railway station and the lagoon's edge. Although somewhat marginal with respect to the issues raised by the Venetian urban structure, this event was ultimately crucial in anticipating issues that would soon after be presented in mature designs at the International Building Exhibition, Berlin (IBA) as part of the critical reconstruction of the contemporary city. Among these were the topographical stratifications and invisible layouts of Eisenman's "intransitive objects"; Hejduk's "masks" of labyrinthine architectural stories; and Rossi's monumental metropolitan fragments (figure 2), such as the Teatro del mondo, which were actually built in 1980 on the unstable Venetian lagoon.16

____________

16. The projects were exhibited in the spring of 1980; a catalogue of the exhibition was published under the title 10 Immagini per Venezia (Rome: Officina, 1980).

Thus, the ideas proposed by Rossi in The Architecture of the City were not limited to laying the foundations of a new architectural approach to issues regarding the city. They raised crucial questions about the nature of architecture and its relationship to other forms of technical and scientific knowledge, and they put forward the notion that architecture could represent itself as an autonomous and independent discipline. In this way, Rossi rehabilitated an essential aspect of the modem tradition that had been overshadowed by the devastation of World War II, when architects, as well as every other intellectual, were obliged to question the essential nature of modern civilization, the notion of progress itself, and their own capacities to interpret, govern, and "design" human destiny, as well as the meaning of history.

Out of this arose both a rejection of the abstract architectural knowledge and power that had provided the foundation for the hegemonic designs of modernism and an attempt to embrace the purifying, pulsating variety of the manifestations of contemporary culture. It looked as if the now age-old dichotomy between technique and culture, and architecture’s long and vain dash to take possession of the world of machinery, might conclude in a pure and simple recognition of the essential identity of architecture as technology, science, and society. The dream of directing the processes of reform in modern society turned into an acknowledgment of mass society's multivalent manifestations. The three-dimensional diagram of DNA, the metal shells of the automobile and the airplane, the new science of cybernetics, the fantastic world of cartoons and movies, the humble materials of spontaneous architecture, the trivial messages of advertising, the dreams and aspirations of ordinary people, and even the unexplored depths of the human psyche became the "found" materials used for experiments carried out by young European architects in the 1950s and 1960s.

Within this perspective, the work of the British architect Cedric Price was seminal. For him, the diagrammatic approach replaced any formal apparatus or abstract geometric system with a dynamic representation of flow, force, and resistance; it disputed the aesthetic nature of architectural practice and the conventionality of its compositional practices. The formula, "seeing everything in relationship,"17 aptly described by the Hungarian artist László Moholy-Nagy in 1947, and so radically challenged by Robert Venturi twenty years later, defined the basic problem of architectural planning as a question of information rather than representation. And Price's visionary (at the start of the 1960s) inclusion of a group of cybernetic thinkers in the planning of the Fun Palace for Joan Littlewood in London of 1964–66 [pages 58–67) clearly confirmed that he intended to write a new scientific rule book for the process of architectural planning.

____________

17. László Moholy Nagy, Vision in Motion (Chicago: Hillison and Etten, 1947): 68.

Rossi's assertion of the existence of an autonomous body of architectural knowledge raised the crucial question of a critical practice of architecture, of the reconquest of analytical tools specific to the city and the territory, and of the forms of their production. The absolute present of mass cultures, "as found," was replaced by a broad awareness of the historical space of Western architecture and, in particular, modernity. Architecture, once again, laid claim to the capacity of not just interpreting the city, but also giving it a new form, of re-forming it in accordance with the distinctive tradition of the modern. Studies of the morphological and typological structures of the city treated the urban phenomenon as the outcome of specific architectural practices, and as a physical whole in which it was possible to recognize describable and reproducible practices and codes.

From the argument presented above, it is clear that the reaffirmation of architecture as a cognitive tool in its own right has been able to produce some formidable results, both on the plane of analytical interpretation and on that of the development of working instruments: the urban project (figure 3). These results become clearly visible in the critical reconstruction of the city attempted in Berlin and in numerous other European cities, as well as in recent American developments such as the growing popularity of so-called new urbanism.

On the other hand, the peculiar kinds of aporia that the "return to order" in Western architecture of the 1970s brought to light are just as evident. At the very moment that the European city was being systematically investigated in its architectural entirety, it was undergoing crucial processes of transformation, which radically changed its structure and the problems it presented, and also shifted these problems from the center to the periphery and, further out still, to ecosystems that could not be reduced to the traditional structures of urban settlement. This encompasses those of corporate centers, shopping malls, de-industrialized swaths of territory with heavy pollution, and massive traffic infrastructures. At the same moment in time, the processes of globalization were introducing new notions of time and space that were wholly extraneous to traditional urban hierarchies and geographies and perfectly capable of operating with indifference to the particular physical organization of the locations.

Nevertheless, it is easy to see the extraordinary impact Rossi produced in Italian—and international—architecture of the late 1960s and early 1970s. The password, autonomy, resounded repeatedly, prompting Italian architects to consider it the foundation of the new practice and the origin of new theoretical questions and dilemmas. Indeed, Giorgio Grassi dedicated his book La Costruzione logica dell' architettura "to considering the terms of autonomy."18 It was published just one year after Rossi's book and in the same year as Ludovico Quaroni's La Torre di Babele, which claimed the architect's right "to determine urban form."19

____________

18. Giorgio Grassi, La Costruzione logica della città (Padua: Marsilio Editori, 1967).

19. Ludovico Quaroni, La Torre di Babele (Padua: Marsilio Editori, 1967).

Figure 2. Aldo Rossi. Large Urban Construction. Project, 1978. Oil and chalk on canvas, 51 1/16 × 35 1/16" (130 × 90 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of the Architecture and Design Committee in honor of Marshall Cogan

In the United States, the founding of the Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies in 1967, followed by the 1972 exhibition Five Architects, and then, the following year, by the publication of the inaugural issue of the architecture periodical Oppositions, were indications that the issue of autonomy in architecture had become central to the theoretical debate in America as well as Europe. And, indeed, it was in Oppositions in 1976 that the architect Diana Agrest offered a clear description of the conditions of autonomy most architectural theorists of the period would have endorsed. She stated: "Design, considered as both a practice and a product, is in effect a closed system—not only in relation to culture as a whole, but also in relation to other cultural systems such as literature, film, painting, philosophy, physics, geometry, etc. Properly defined, it is reductive, condensing and crystallizing general cultural notions within its own distinct parameters. Within the limits of this system, however, design constitutes a set of practices—architecture, urban design, and industrial design—unified with respect to certain normative theories. That is, it possesses specific characteristics that distinguish it from all other cultural practices and that establish a boundary between what is design and what is not,"20

____________

20. Diana Agrest, "Design versus Non-Design," Oppositions 6, (Fall 1976); reprinted in K. Michael Hays, ed., Oppositions/ Reader (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1998): 333.

Figure 3. Aldo Rossi. Urban Architecture. Project, 1976. Perspective: oil pastel, ballpoint pen, ink, and felt-tipped marker on paper with tape, 14⅛ × 10⅛" (35.9 x 25.7 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Barbara Jakobson Purchase Fund

Just two years after the Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies in New York City was created under the aegis of Arthur Drexler and The Museum of Modern Art, the German architect Oswald Mathias Ungers (page 100), then at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York, whose architecture program was dominated by the ideas of Colin Rowe, tried to offer another formulation of a radical reconsideration of architecture. He and the other members of the European group Team X had reached an end point in their architectural practice, and a certainty of the necessity of bringing the essential issue of architecture back inside its historic disciplinary boundaries; of rediscovering the basics of planning practice that were consistent with the requirements of architectural form; and of redefining the relationships linking the architectural work and its rules of typology with the morphological structure of the city.21 This view was soon more or less shared by other European planners, such as Aldo Rossi, Vittorio Gregotti, and James Stirling. But it was equally evident that there was a growing awareness of the irreparable dissolution of a systematic architectural knowledge. Anyone who looked at the history of the discipline saw in it a jumble of elements and impressions that added up to a many-sided and fragmentary collage, rather than a new composition as an organic whole.

____________

21. On this topic, see my "Architectura artificialis," in O. M. Ungers 1991–1998 (Milan: Electa, 1998): 9–18.

For almost eleven years, until the end of the 1970s, Ungers declined to practice as a professional architect, preferring teaching and a lengthy silent consideration of the possibility of rebuilding the essential foundations of architecture. I believe it is not a coincidence that it was Ungers who brought two particular young architects, Léon Krier and Rem Koolhaas, to Cornell University during those years. While Krier and Koolhaas, working with Elia Zenghelis, used methods that turned out to be quite different, they both were determined to sweep away the lingering optimism of the remaining members of Team X, the technocratic rhetoric of Archigram in London, as well as that city's prestigious school of architecture: the Architectural Association. In a recent interview, Zenghelis spoke of a battle that he fought back then, together with Superstudio in Italy, for "the rehabilitation of architecture."22

____________

22. Elia Zenghelis, "Interview," in Luka Skansi, "Rem Koolhaas: Scritti, architettura 1963–1978," Ph.D. diss., IUAV, Venice, 2002; 265–377.

The movement to replace modernism with a new kind of autonomy appeared in many other instances and numerous guises, none of them coordinated formally with the others. It is also important to note that these were years of extraordinary political tension, especially in Europe, which exploded in 1968 and then in the terrible terrorism of the 1970s. But it is still necessary to attempt to interpret the reasons behind the relentless assertion of this rediscovered notion of autonomy, which seemed to open an extraordinary new potential for intervention but, even more, to exorcise the dread of the social demise of architecture.

The emergency of postwar reconstruction was over and the social-democratic call for a general reform of the political and economic apparatus had given way to an obstinate impotence, especially in Italy. The architects' call to order took on a peculiar and contradictory—even political—meaning. With the rediscovery of its own autonomy, it seemed that architecture had played its last card for a progressive role in the culture, the only possibility of representing, in architectural practice, the contradictions of the contemporary city through solutions whose "finished form" could, ironically, also present "a possible example of a different urban structure."23

____________

23. Marino Folin, La Città del capitale (Bari: De Donato Editore, 1972): 20–21.

The special attention reserved, in those years, for issues related to the "socialist city" confirms this particular aspect of the question of autonomy. It was aimed primarily at the rediscovery of Soviet architecture and its avant-garde, Constructivist, and formalist movements. But it also concerned the experience of Cuba, and, in a peculiar way, that of East Germany, where the effort toward a general industrialization of the building industry seemed consistent with experimentation with a typological approach to housing design and demonstrated the crucial importance of morphological issues for the planning of new socialist settlements.

It was not merely by chance that one of the first meetings of what would later become the Tendenza group actually took place during a trip through socialist Germany in 1970, in front of the grand marble flags of the Soviet war memorial, built with red granite from Hitler's chancellery. The group of Italian architects around Aldo Rossi, Giorgio Grassi, Guido Canella, and Carlo Aymonino, chose the name Tendenza, or trend, which expressed the political dilemma that embarking upon a new path in architecture appeared feasible only if it began from a reflection on the meaning and historical nature of the practice. As Canella affirmed in December 1968: "It has become evident that architectural culture needs to withdraw into itself and attempt an autonomous, constructive balance, which globally puts into play the distances and lacerations between current practice and a presumed theoretical and practical future."24

____________

24. Guido Canella, quoted in Gruppo Architettura, "Introduction," in Per una ricerca di progettazione 1 (Venice; IUAV, 1969): 7.

At this point, Manfredo Tafuri's theoretical work appeared on the scene and bad a dramatic destabilizing effect. It could be said that, early on, Tafuri became aware that the final outcome of this process would be none other than retreat into the solitary subjectivity of architectural practice. Rossi would also recognize this a few years later in his Scientific Autobiography, where he stated that while writing The Architecture of the City, he "had perhaps simply wanted to get rid of the city and, in reality, he discovered his architecture." His "insistence on things, revealed his craft."25

____________

25. Aldo Rossi, Autobiografia scientifica (Parma: Pratiche Editrice, 1990): 22; orig. ed., A Scientific Autobiography (New York, 1981).

Tafuri followed the question back to a critique of the notion of architectural modernity itself in his essay "Toward a Critique of Architectural Ideology," which was published in 1969 and further developed in Architecture and Utopia in 1973.26 Between the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, in the very moment in which architecture had "discovered its scientific vocation," it had also accepted its political role. Here Tafuri recalled Quatremère de Quincy's definition of architecture in his Encyclopédie Méthodique (1788–1825): it "sees to the salubrity of cities, guards the health of men, protects their properties, and works only for the safety, repose and orderliness of civic life."27

____________

26. Manfredo Tafuri, "Per una critica della ideologia architettonica," Contropiano 1 (January–April 1969); English trans. in K. Michael Hays, ed., Architecture: Theory since 1968 (New York: Columbia Books on Architecture, 1998): 9. See also Manfredo Tafuri, Progetto e utopia (Rome and Bari: Laterza, 1973).

27. Tafuri, "Per una critica della ideologia architettonica."

The only problem was that the very establishment of science and technique as independent bodies of knowledge separated and isolated architecture from the real processes of conformity to modern society and condemned it to a labored and irresolvable course. This, for Tafuri, is the origin of the ideological nature of any architectural work: the fact of not being the protagonist of the real transformations that capitalistic development produces, but of merely being able to interpret them a posteriori. It could be said that architecture was no longer content to give form to reality but, at most, to re-form it [reform being a key word of modernity), to intervene a posteriori in order to ensure the rationality and the harmonious balance capitalistic development did not essentially possess. For all these reasons, Tafuri observed: "Architectural ideology, in both its artistic and urban forms, was left with the utopia of form as a project for regaining the human Totality in the ideal Synthesis, as a way of mastering Disorder through Order."28

____________

28. Ibid.: 15.

But, then, what sense could operative criticism—that "used/abused past history projecting it toward the future"29—have for Tafuri in the face of the ruinous fragments of the crisis of modernity? At this point it is interesting to reread the essay published by Massimo Scolari in 1973 in the catalogue of the exhibition Rational Architecture, organized by Aldo Rossi at the Triennale di Milano. This text can he considered a theoretical manifesto of Tendenza and the exhibition, one in which Rossi tried to present the international panorama of autonomous architecture, showing, alongside the Italians, such architects as James Stirling, Léon and Rob Krier, Oswald Mathias Ungers and Ludwig Leo from Germany, as well as the Five Architects from America: Richard Meier, Peter Eisenman, John Hejduk, Charles Gwathmey, and Robert Stem. For Scolari, the progressive character of the rediscovery of architecture's disciplinary autonomy lay in recognizing the historical basis of its very tools of analysis and intervention, as opposed to the utopian season of the avant-garde; "In its will to start over again from nothing, it denies history in order to find another point of departure, however illusory; and in so doing it easily achieves utopia and its isolation from reality. In short, it plays an essentially reactionary role, since, with its self-exclusion, it helps to reinforce the situation it wanted to destroy."30 Having dismissed the entire Italian neo-avant-garde in that way (like the radical Florentine Archizoom and, in an even more subtle way, Superstudio), with the clear intention of sheltering Tendenza from Tafuri's reflection on the ideological nature of the experience of the avant-garde movements, Scolari tried to define a "critical" condition for the strategy of architecture's "autonomization": "For Tendenza, architecture is a cognitive process that in and of itself, in the acknowledgment of its own autonomy, now necessitates a re-founding of the discipline: one that refuses interdisciplinary solutions to its own crisis, that does not pursue and immerse itself in political, economic, social, and technological events only to mask its own creative and formal sterility, but rather desires to understand them so as to be able to intervene in them with lucidity."31

____________

29. Manfredo Tafuri, Teorie e storia dell’architettura (Rome/ Bari: Laterza, 1968): 165.

30. Massimo Scolari, "Avanguardia e nuova architettura," in Architettura razionale (Milan: Franco Angeli, 1973); English trans. in Hays, Architecture: Theory; 128.

31. Ibid.: 131–132.

Thus, for Scolari, Tendenza was not a stylistic mask but a system itself. The operative elements of this system were set out in Aldo Rossi's The Architecture of the City: the distributive indifference of the type as a principle of architecture; the migratory characteristics of types; and the affirmation of a new simplified monumentality, defined by a few decisive rules, that was to bring unity and simplicity to the disorder of the modern city (see figure 4).32

____________

32. Rossi, Architecture of the City.

Scolari's attempt to exorcise Tafuri's criticism went as far as to identify the Roman historian as "one of the most passionate 'planners' of Tendenza, since the relationship to history contains a well-defined project, entirely thought out but no less important or suggestive than those that are 'only' designed."33 After having gotten beyond the apocalyptic dilemma of the "death of architecture" proposed by Tafuri in his 1968 essay in Contropiano,34 Scolari read Tendenza to make Tafuri's interpretation of the drama that characterized architecture in those years its own, "that of seeing itself forced to turn back to pure architecture, an instance of form devoid of utopia, a sublime uselessness in the best of cases. Yet to the mystified attempts to dress architecture in ideological clothing, we shall always prefer ... the sincerity of those who have the courage to speak that silent, unrealizable purity."35 In other words, Aldo Rossi!

____________

33. Scolari, "Avanguardia."

34. Tafuri, "Per una critica della ideologia architettonica."

35. Scolari, "Avanguardia."

But what Tafuri had questioned was precisely the political meaning of the attempt to recompose a unity for the discipline of architecture, to be able to finally give form to a new "treatise of composition" of which Scolari spoke. For Tafuri, the utopia of the form had by now taken on the physiognomy of the "mask": it had become an instrument for hiding the complexity of the real world.

The sullen indifference of Rossi's architecture evidenced the awareness of the disillusionment of Italian architects during the reforms of the 1970s. The project for Modena's Cemetery of San Cataldo (pages 110–115) turned its back on the noise of the world. For Tafuri, "The thread of Ariadne with which Rossi weaves his typological research does not lead to the reestablishment of the discipline, but rather to its dissolution."36

____________

36. Tafuri, "Per una critica della ideologia architettonica": 133.

Rossi presented the concept of the analogous city at the Venice Biennale in 1976, announcing the theory "that it could be understood as a compositional procedure 'centered on some primary facts of urban reality around which other facts are constituted within the frame of an analogical system.'" Whereupon Tafuri titled his review: "Ceci n'est pas une ville," a play on the famous title of René Magritte's calligramme: "Ceci n'est pas une pipe."37 For Tafuri, Rossi's "collage" was completely within the negative tradition of the modernist avant-garde: his message "is at once the manifestation of a negation and an interweaving of subjective impulsions and reality."38 It confesses the definitive impossibility of giving a new order, of attributing a new meaning to the city and, therein, unmasks the purely ideological character of Rossi's pretense of constructing a "theory of the city" capable of governing its transformations. In Tafuri's "L’Architecture dans le boudoir," published Oppositions in 1974, we can read: "He who wishes to make architecture speak is thus forced to resort to materials devoid of all meaning; he is forced to reduce to degree zero every ideology, every dream of social function, every utopian residue. In his hands, the elements of the modern architectural tradition are all at once reduced to enigmatic fragments—to mute signals of a language whose code has been lost."39 At this point, the path of contemporary architecture broke off, irreparably, from Tafuri's historical project.

____________

37. Manfredo Tafuri, Storia dell'architettura italiana 1944–1985 (Turin: Einaudi, 1986): 166.

38. Ibid.

39. Manfredo Tafuri, "L'Architecture dans le boudoir," Oppositions 3 (1974); reprinted in Hays, Architecture: Theory since 1968: 155.

Tafuri's "total disenchantment" was testimony of his awareness that there was nothing more to be found in the "hypnotic solitude" of the architecture he loved to call "hypermodern." In 1969, he had written: "There is no more salvation to be found within modern architecture: neither by wandering restlessly through labyrinths of images so polyvalent that they remain mute, nor by shutting oneself up in the sullen silence of geometries content with their own perfection."40

____________

40. Tafuri, "Per una critica della ideologia architettonica."

This dilemma still seems to raise the passions of whoever takes the time to interpret Tafuri: the reasons for his abandonment of the passionate confrontation with contemporaneity and his apparent retreat into the more conventional territories of philology and the Renaissance. For Tafuri, the autonomy of the historiographic project had its foundation in a condition of conflict between the process of analysis and its objects. The historical project was always one of crisis, nourished by "notions as hard as stone."41 One of these was the long unitary and progressive myth of modernity. What remained, in his eyes, were only fragments. By now, Tafuri had moved on and was busily engaged in studying the Italian Renaissance, an epoch of history where wisdom and power still truly blended and where the forms of architecture did not seem to be separable from those of thought.

____________

41. K. Michael Hays, "Tafuri's Ghost," in ANY 25/26 (2000): 36.

Figure 4, Aldo Rossi, Constructing the City. Project, 1978. Oil and chalk on canvas, 51 3/16 × 35 7/16" (130 × 90 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of the Architecture and Design Committee in honor of Marshall Cogan

Thus the crisis of autonomous architecture of the late 1970s is attributable not only to the growing awareness of the relativity of architecture as just one of numerous subjects and means of contemporary communication, but to the parallel acceptance of a mise en abîme within the various, now fragmented, critical practices.

5 сентября 2025, 2:39

0 комментариев

|

Партнёры

|

Комментарии

Добавить комментарий