|

|

Sarah Deyong. Memories of the urban future: the rise and fall of the megastructure

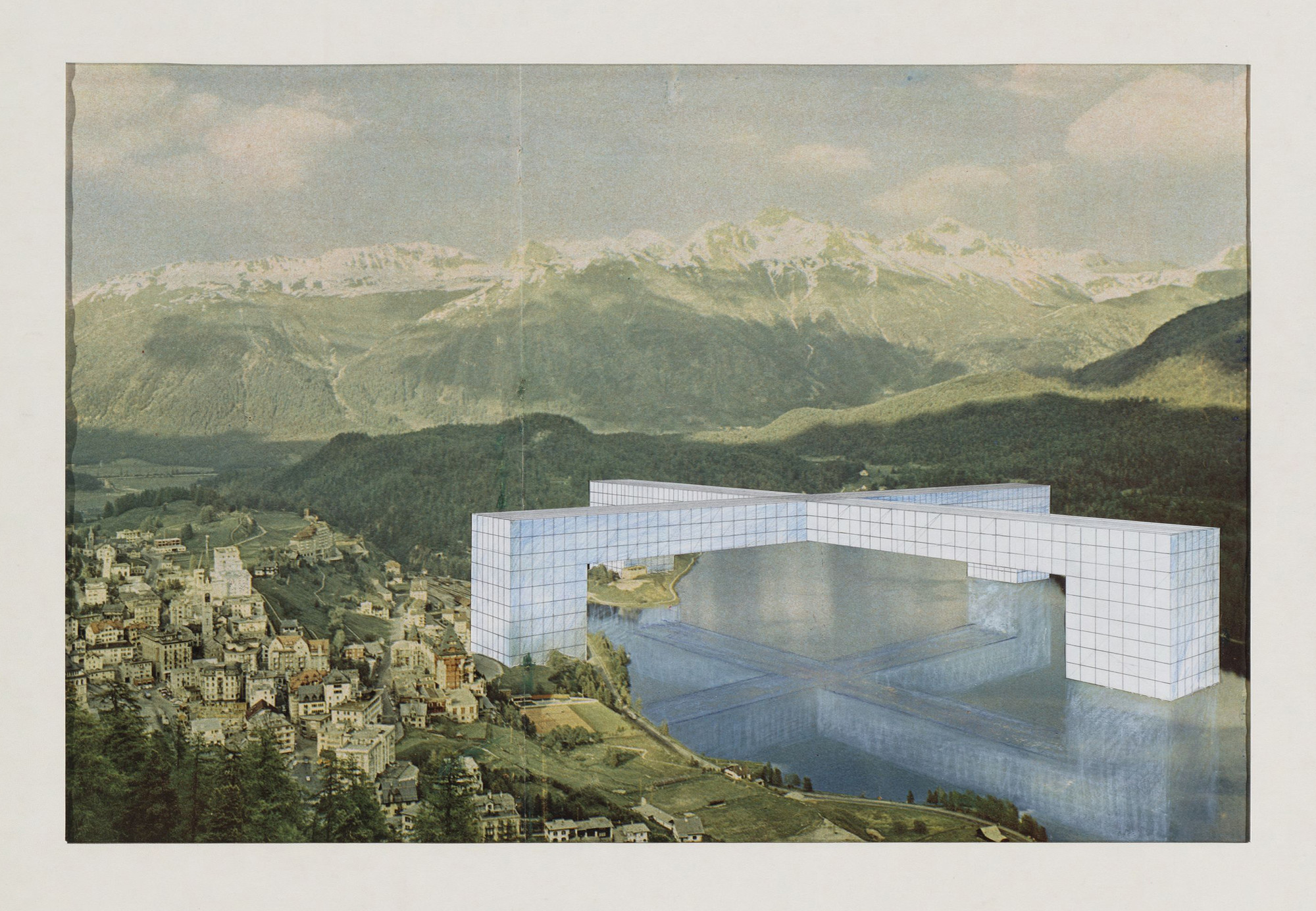

Superstudio, Cristiano Toraldo di Francia, Gian Piero Frassinelli, Alessandro Magris, Roberto Magris, Adolfo Natalini. The Continuous Monument: On the River, project (Perspective). 1969

MEMORIES OF THE URBAN FUTURE: THE RISE AND FALL OF THE MEGASTRUCTURESarah Deyong

When the imagination surpasses the limits permitted hy the institution of culture, one speaks of poésie, utopia. When critical thought attains and surpasses its limits (which are much more severe than those of the imagination), one speaks of deviance, folly, a critical error, an overly theoretical system, a free-floating vision, etc. When the event attains and surpasses the limits permitted by the law, one speaks of revolution. Or of histories for daydreaming.

— René Lourau1

____________

1. René Lourau, "Contours d'une pensée critique nommé urbanisme," Utopie 1 (May 1967):

11–12; "Quand l’imagination atteint et dépasse les limites permises par l'institution de la culture, on parle de poésie, d'utopie. Quand la pensée critique atteint et dépasse ses limites (beaucoup plus sévères que celles de l'imagination), on parle de déviance, de folie, d'erreurs graves, de système trop théorique, de vision gratuite, etc. Quand l’événement atteint et dépasse les limites permises par la loi juridique et par les règles anomiques, on parle de révolulion. Ou d'histoires à dormir debout.”

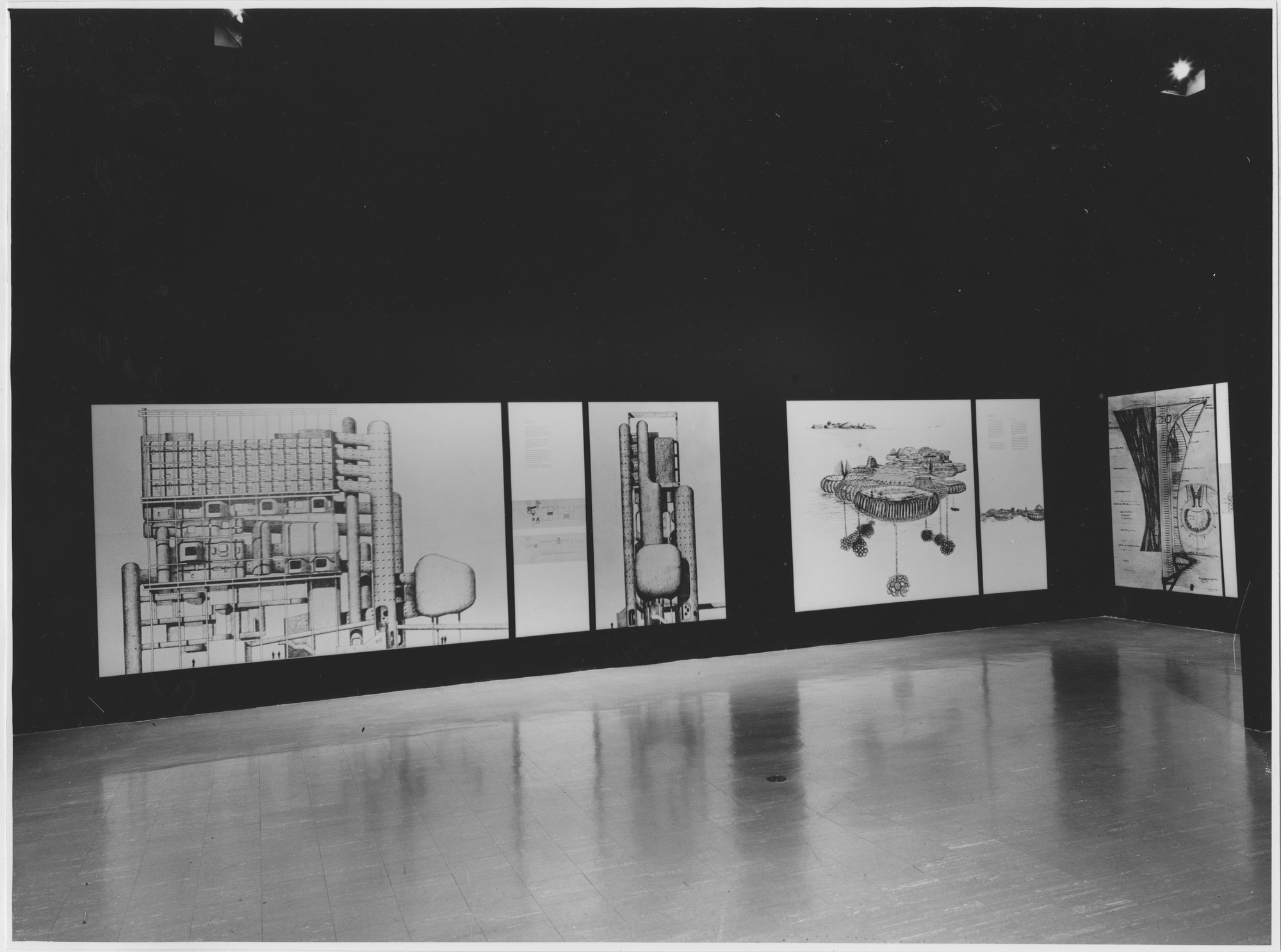

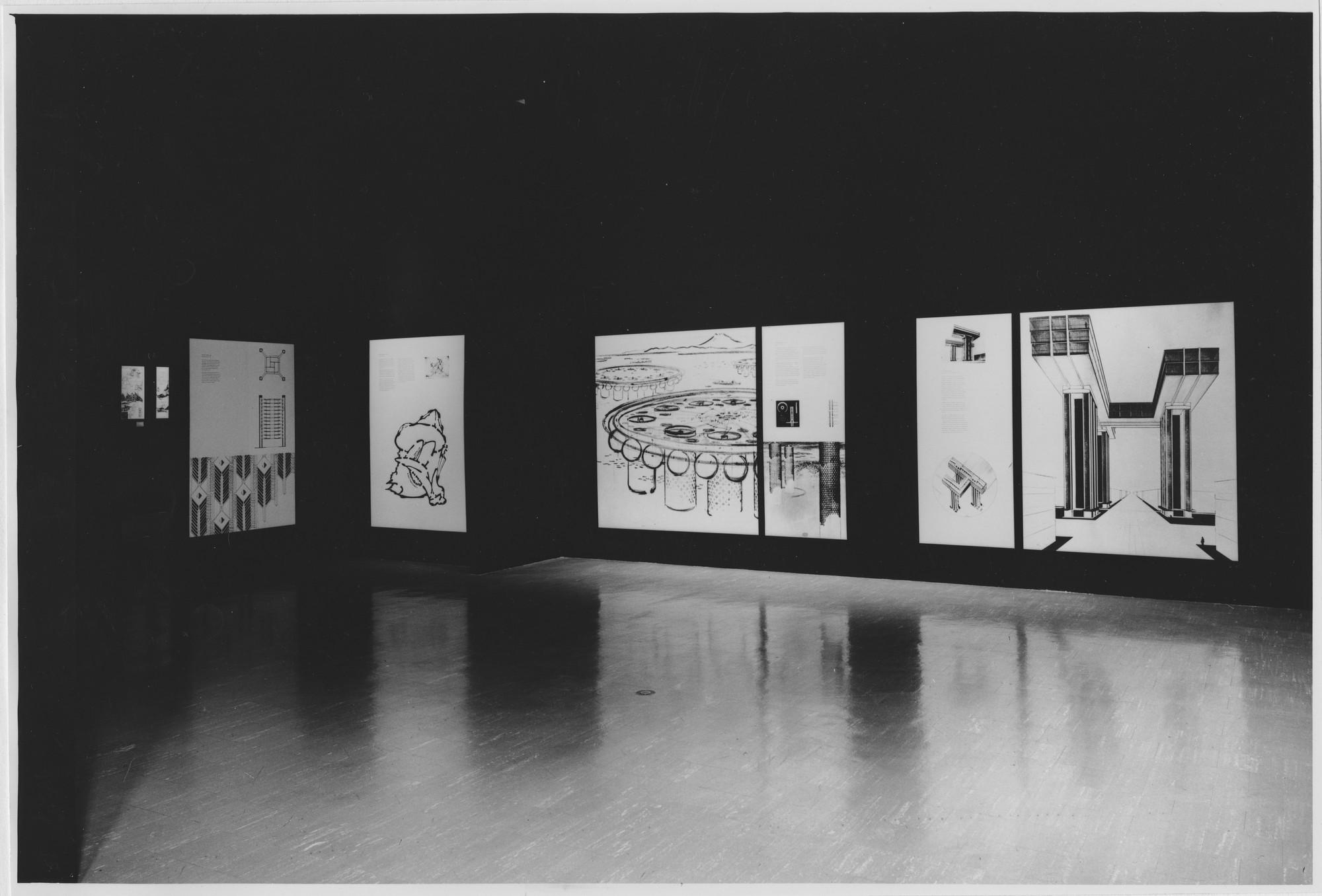

In 1960, The Museum of Modern Art inaugurated what might well be called a decade of metaphoric transformation in modern architecture with an exhibition titled Visionary Architecture (figure 1). The exhibition, organized by Arthur Drexler, showed a dazzling collection of urban proposals, including such projects as the Metabolist Kiyonori Kikutake's Floating City (1959), R. Buckminster Fuller's Dome over Manhattan (1950), and Paolo Soleri's Arcology (1959). The show was widely considered a landmark event, because it was the first major exhibition to herald a new development in modem architecture, more commonly known as the megastructure, which had been brewing since the mid-1950s, and flowered in the early to mid-1960s with the advent of such groups and individuals as Kenzo Tange and the Metabolists (pages 49, 101) in Japan; Archigram and Cedric Price (pages 38–39, 44–48, 50–67) in Britain; the Groupe d'Espace et d'Architecture Mobile (GEAM), Architecture Principe, and Utopie in France; Hans Hollein, Friedrich St. Florian (page 68–70), Haus Rücker Co., and Coop Himmelblau in Austria; and Archizoom, Ettore Sottsass, and Superstudio (pages 73–87, 102) in Italy. For these young architects, the megastructure represented a new vision of modernity unhindered by the social and technical constraints of the past. Like the pioneers of modern architecture of the early twentieth century, their aim was to bring about a utopian transformation of the built environment at a scale and speed as yet unseen. But in little more than a decade, this architecture came to an end. As the GEAM member Manfredi Nicoletti summarized the phenomenon upon its demise: "Never—perhaps—in the history of architecture [has] such a large availability of ideas and practical means corresponded [to] such a tremendous chance of creating. It is appalling to witness, in this moment, how problematic the encounter between the possible and the concrete has become. We are actually facing a sort of paradoxical reality that has all the features of a utopia."2

____________

2. Manfredi Nicoletti, "The End of Utopia," Perspecta 13/14 (1971): 276.

Figure 1. Visionary Architecture, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, September 29–December 4,1960, Installation view

Visionary Architecture, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, September 29–December 4,1960, Installation view

Visionary Architecture, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, September 29–December 4,1960, Installation view

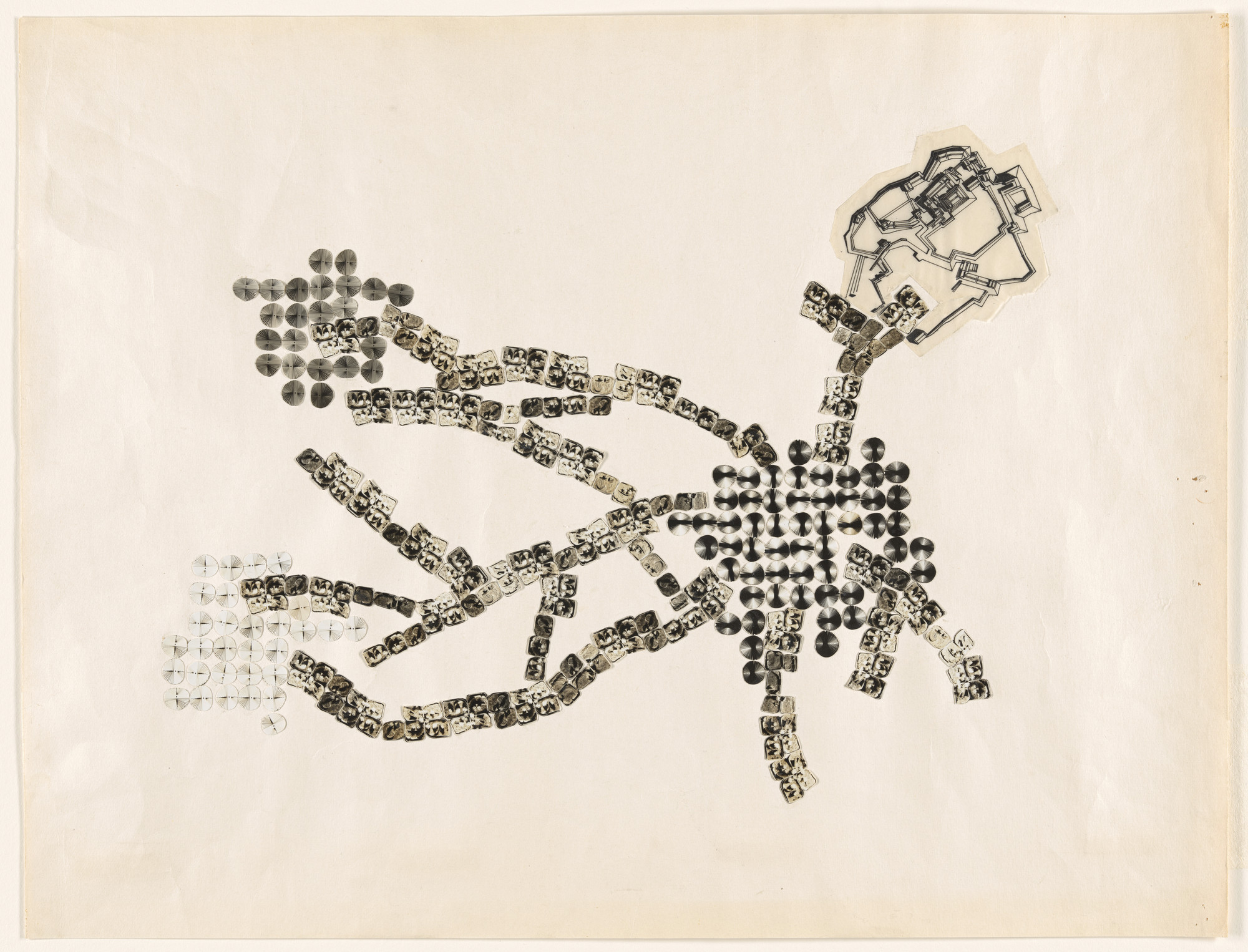

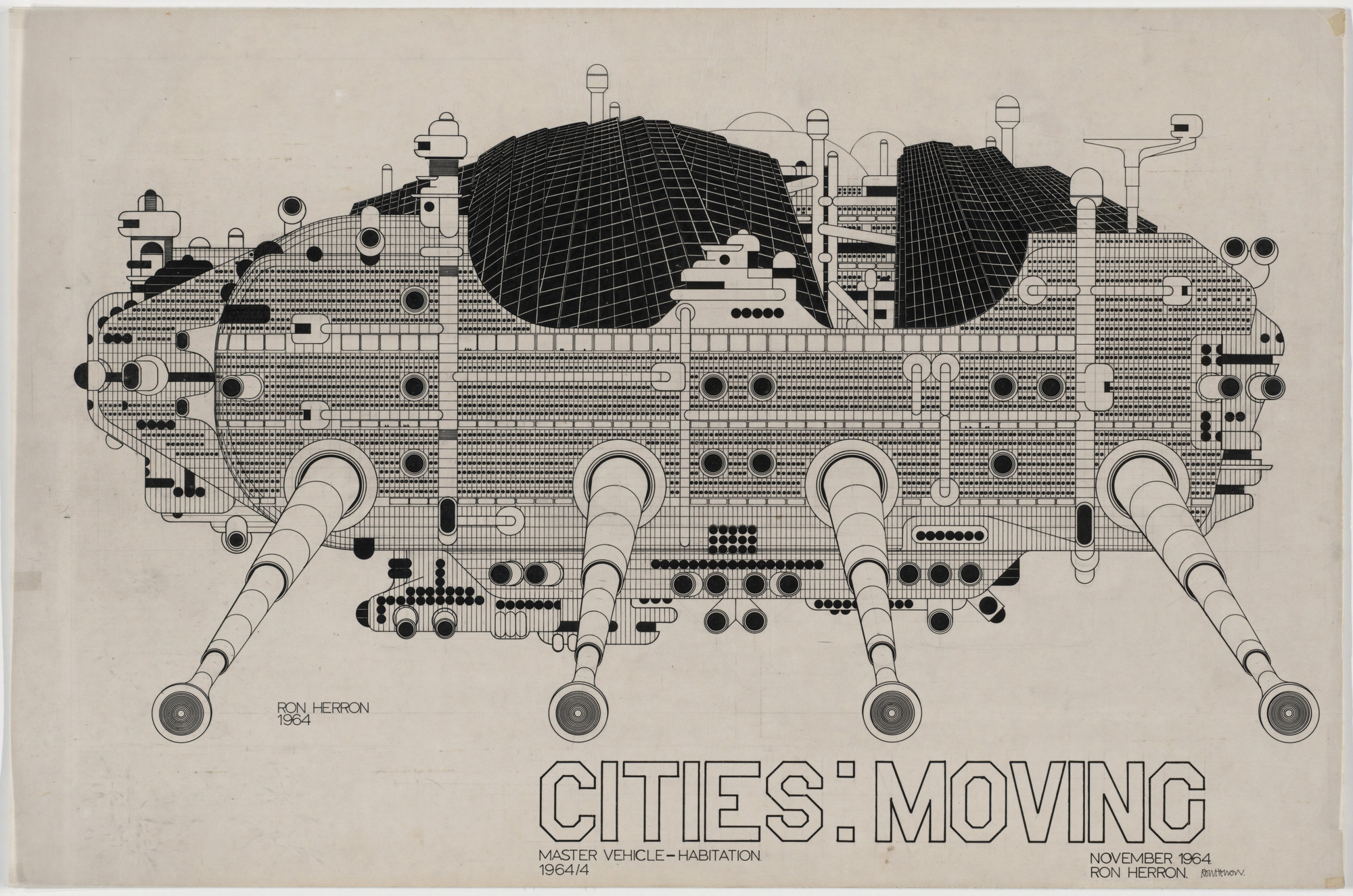

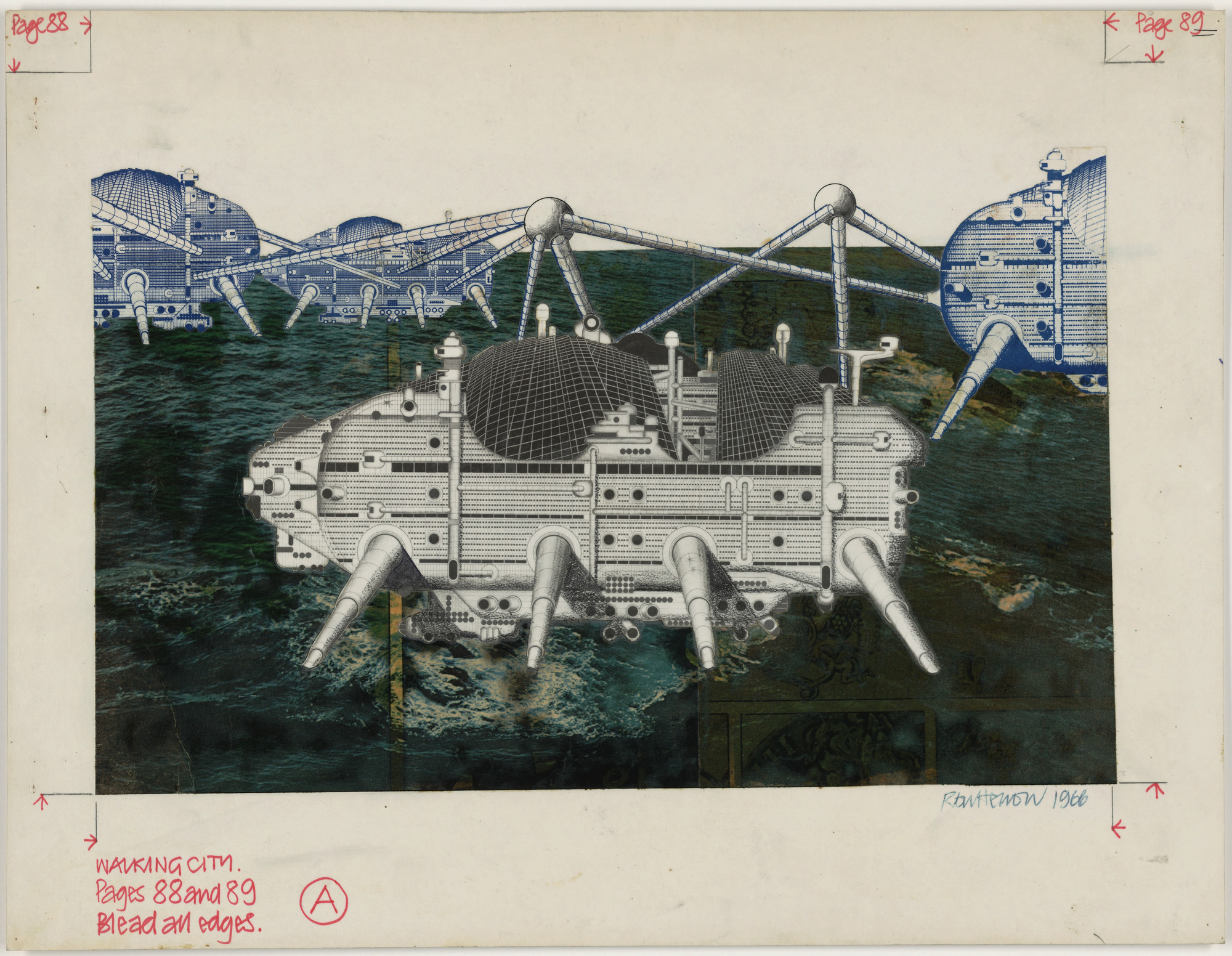

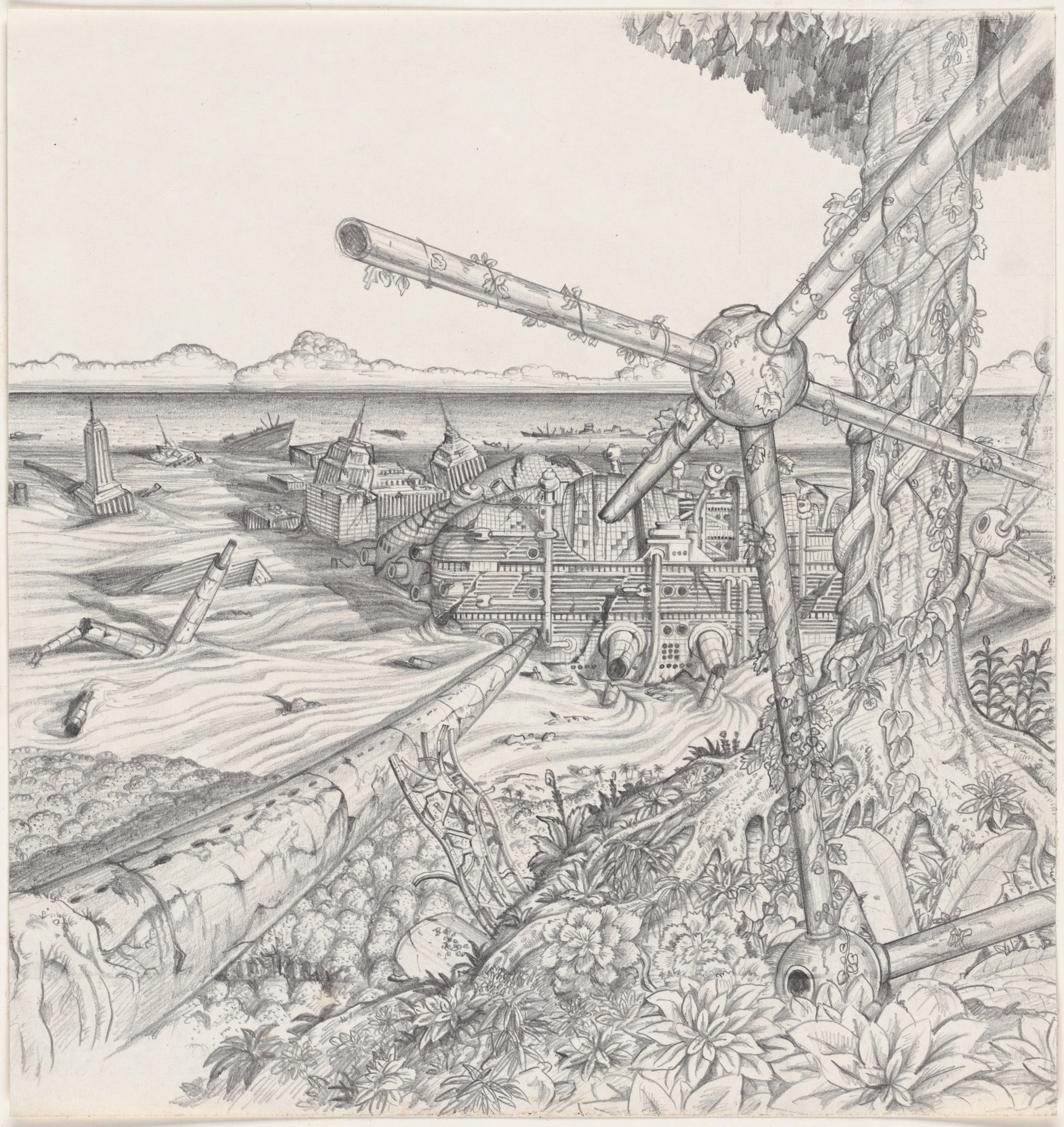

Among the most provocative and influential projects of the early 1960s were Yon a Friedman's mobile architecture and spatial cities (pages 40–43); Metabolist Kisho Kurokawa's Helix City project (figure 2), a vertical city in the shape of a DNA molecule of 1961; Archigram's monumental urban machines: Peter Cook's Plug-In City of 1962–65 (pages 50–53), Ron Herron's Walking City of 1966 (page 55); and Dennis Crompton's Computer City (1964). Such projects were testimony to the postwar optimism for the new technology in communications, molecular biology, and the space program; but it was an optimism that quickly dissipated with the escalation of the Vietnam War and the increasing radicalization of politics, culminating in the student demonstrations of May 1968. By the late 1960s, the megastructure had lost much, if not all, of its avant-garde appeal; and visionary architects found themselves under attack for their love affair with technology, mass communications, and consumer goods, on the one hand, and for their failure to create anything more than just images of the future, on the other. Contrary to expectations, the transformation of vision into reality never came to pass, and the utopian aspirations of the modern movement were as remote as they had ever been. What had once seemed like an opportunity to transform the whole configuration of society became a memorial to "an ideal and unreachable destiny," or as the architectural historian Reyner Banham put it, "a whitening skeleton on the dark horizons of our recent past."3 Such criticism came not only from disenchanted observers, like Banham, but from key figures from within the megastructure movement itself. Ettore Sottsass and Superstudio, for example, acknowledged the demise of the movement in drawings featuring their own megastructures in mythical, ruinous, or apocalyptic scenarios: Sottsass's The Planet as Festival of 1972–73 (pages 80–87) and Superstudio's The Continuous Monument of 1969 (pages 73–77). Although the megastructure was originally intended as a corrective to the modem project, in the end it led to another and final impasse. This impasse was not the result of technological, social, or political constraints, but grew out of the logic of the modern discourse itself.

____________

3. Ibid.: 270; see also Reyner Banham, Megastructure: Urban futures of the Recent Past (New York: Harper & Row, 1976): 11.

The French sociologist and cultural critic, Jean Baudrillard, has explored this impasse in an exemplary way: his concept of the simulacrum, formulated in the mid-1970s, helps to explain some of the internal contradictions and paradoxes of the megastructure movement. Baudrillard himself was a member of Utopie, an avant-garde collective of Marxist sociologists, architects, and urban theorists who mounted a devastating critique of visionary architecture at a 1969 conference in Turin, titled "Utopia e/o Rivoluzione," in which they denounced the megastructures of Archigram, Paolo Soleri, Yona Friedman, and others as "chimera of utopia." Baudrillard later extended this critique (in part, by turning it against itself) to an analysis of the mass media, popular culture, and modern science in what many consider his most important work, his essays on the simulacrum during the second half of the 1970s: "The Orders of Simulacra" (1976); "The Beaubourg Effect" (1977); and "The Precession of Simulacra" (1978). These essays on the vicissitudes of modern culture offer considerable insight into the rise and fall of the megastructure. In exploring visionary architecture in terms of Baudrillard's theory, I propose to focus on two key points in the life of the movement: its beginnings in the late 1950s and early 1960s, with Team X, Yona Friedman, and the Metabolists, and its end after the political events of May 1968, with Utopie and Superstudio.

Figure 2. Kisho Kurakawa. Helix City, Tokyo, Japan. Project, 1961. Plan: cut-and-pasted gelatin silver photographs and ink on cut-and-pasted tracing paper on paper, 21½×17½ (54.6×44.5 cm)". The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of the architect, 1992.

THE LIVING CITY

In the postwar period, the International Congress of Modern Architects (CIAM), founded in 1928, had grown into the largest and most important organization to promote the ideas of modern architecture. Among other activities, it created a set of guidelines on urban planning, called the Athens Charter, which was widely implemented in the reconstruction of postwar Europe. And yet, at the height of its success in the 1950s, the organization came to be discredited from within its ranks by a younger generation of CIAM architects, soon-to-be-named Team X for the meeting they organized collectively: the tenth CIAM congress in Dubrovnik, Yugoslavia, in 1956. In the mid-1950s, this group of architects, which included Alison and Peter Smithson, Jacob Bakema, and Aldo van Eyck, criticized the charter for fragmenting the city artificially into four functional zones (work, living, recreation, and transportation). In its place, they established a new urban agenda, emphasizing the need for reintegrating the various functions of the city into a hierarchical "cluster" of "associational elements" (house, street, district, and city).4 Although CIAM itself dissolved just a few years later, in 1959, it was this new agenda that laid the groundwork for the first megastructures by Yona Friedman and the Metabolists.5

____________

4. Alison and Peter Smithson, "Town Structure," in Jürgen Joedicke, ed., Documents of Modern Architecture: CIAM '59 in Otterlo (New York: Universe Books, 1961): 68.

5. The Metabolists included Kiyonori Kikutake, Kisho Kurokawa, and Fumihiko Maki. Kenzo Tange and Arata Isozaki were closely affiliated with the group.

The aim of the new agenda was to revisit what the Athens Charter had inadequately addressed; as Team X declared: "Life falls through the net of the four functions."6 This critique had less to do with the functionalist precepts of modernism than with the technological model on which those precepts were based. "We are still functionalists," wrote Team X member Peter Smithson, "but today the word functional does not merely mean mechanical, as it did thirty years ago."7 If the old Athens Charter addressed certain problems of mass urbanization, such as pollution, congestion, and disease, for Team X it also reduced the city to a bureaucratic machine, a huge factory bereft of the ingredients that made the city a vital and complex organism. In its prescriptions to fellow practitioners at Dubrovnik, Team X wrote: "Today we each recognize the existence of a new spirit. It is manifest in our revolt from the mechanical concepts of order and in our passionate interest in the complex relationships of life and the realities of our world."8 The megastructure was an attempt to enact, through built form, "the complex relationships of life," conceived along the lines of a new technological model. But rather than exemplify an architecture and town planning that restored the "realities of the world," it played out, avant la lettre, the logic of what Jean Baudrillard has called the simulacrum.

____________

6. Alison Smithson, ed., Team 10 Meetings (New York: Rizzoli, 1991): 9.

7. Peter Smithson, "Cluster City," Architectural Review (November 1957): 333.

8. Team X, "Instruction to Groups, Dubrovnik 1956," in Joedicke, Documents of Modern Architecture: CIAM '59 in Otterlo: 14.

When Team X declared its "revolt against the mechanical concepts of order" and its "passionate interest in the complex relationships of life," the group broached the age-old metaphysical question: What is life? In rejecting the mechanical concepts of order on which the Athens Charter was based, they displaced the Cartesian model of life, which explains living phenomena in terms of clockwork mechanisms and automatons, with what is called in biology the holistic or organismic model. Beginning with the supposition that cities are complex organisms, Team X rehearsed the speculations of organismic biologists, such as Ludwig von Bertalanffy, arguing that the city is more than the "sum of its parts," that it forms a "synthetic whole" possessing the characteristics of an "organized complexity." "The problem," Team X wrote, "is one of developing a distinct total structure for each community, and not one of subdividing a community into parts.... We must find ways of weaving new units into the whole cluster so that they extend and renew the existing patterns."9 This understanding of the living process was rooted in a philosophy that was regarded as elusive and inestimable until the mid-twentieth century. With the rise of cybernetics after World War II, life was no longer seen as a transcendental ideal, an unsolvable mystery, but as something that could he mapped, and ultimately reproduced.

____________

9. Team X, "The Tenth Congress of CIAM, Dubrovnik, August 1956," in Alison Smithson, Team 10 Out of CIAM (1982): 73.

Visionary architects, as Arthur Drexler was to point out, were in the business of creation, of transforming vision into reality or, rather, models of life into reality itself.10 In the early to mid-1960s, the Archigram group and other young architects heralded the potential of new technology to bring about a utopian transformation of society, but it was not just an advance in technology that made possible this equation between vision and reality, but a shift in the conceptualization of life from an undecipherable unity to an organized complexity regulated by a cybernetic feedback system.11 In the 1950s, the organismic model, which extends back to the nineteenth century, was recast in terms of cybernetics, the science of communication and control, and as such, the unity of life came to be associated with self-regulating systems of communication, akin to the guidance and control mechanism of a ballistic missile. In James Watson's and Francis Crick's 1953 description of the double-helix structure of DNA, for example, life consisted of a program tape comprising the four "letters" of the genetic code (A, C, T and G) that regulated "the assembly of twenty amino acids into myriads of proteins."12 While the concept of an organism in terms of a cybernetic system empowered scientific discourse with a newfound rigor and precision, its application was more rhetorical than practical and was limited in scope: although cybernetics could explain chemical processes at the molecular level, for example, it could not explain cell differentiation, that is, how new qualities emerge in the biological world at each successive level of organization. And yet, despite this limitation, the notion of life as a cybernetic machine managed to frame and influence research in vast areas of the behavioral and social sciences, and in modern architecture and urban planning as well.13 Soon after attending the tenth CIAM congress in Dubrovnik, Friedman proposed a mobile system of town planning, equipped with its own cybernetic feedback mechanism.14 Although the proposal went largely unnoticed by Team X, it caught the attention of other CIAM members, such as Eckhard Schulze-Fielitz and David Georges Emmerich, who, together with Friedman, founded the Groupe d'Espace et d'Architecture Mobile (GEAM), as well as Kenzo Tange, the so-called father of the Metabolists.15

____________

10. As Arthur Drexler wrote in a statement on the Visionary Architecture exhibition: "Today virtually nothing an architect can think of is technically impossible to realize. Social usage ... determines what is visionary and what is not. ... Visionary projects, like Plato's ideal forms, cast their shadows over into the real world of experience, expense and frustration. If we could learn what they have to teach, we might exchange irrelevant rationalizations for more useful critical standards. Vision and reality might then coincide." See "Visionary Architecture," The Museum of Modern Art, New York, Press Release No. 108, September 29, 1960.

11. For an excellent discussion on the rhetoric of molecular biological discourse, see Richard M. Doyle, "Emergent Power: Vitality and Theology in Artificial Life," in Timothy Lenoir, ed., Inscribing Science (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1988); 304–433.

12. Lily Kay, "How a Genetic Code Became an Information System," in Agatha C. Hughes and Thomas P. Hughes, eds., Systems, Experts, and Computers (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2000): 463.

13. Ibid.: 465: "The representation of phenomena in terms of information systems was not confined to molecular biology. Nearly every discipline in the social sciences (sociology, psychology, anthropology, political science, and economics), as well as in the life sciences (immunology, endocrinology, embryology, physiology, neuroscience, evolutionary biology, ecology, and molecular genetics) flirted with the seductive ideals of cybernetics and information theory in the 1950s, with different degrees of productivity and commitment."

14. Yona Friedman, "L'Architecture mobile," December 12, 1958, typescript in the Yona Friedman Files, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris.

15. The Metabolists first came together as the Theme Committee for the 1960 World Design Conference in Tokyo. For this event, they published a manifesto, titled Metabolism 1960: Proposals for the New Urbanism. The group's spiritual father was Kenzo Tange, who had been a CIAM member since 1949. Kurokawa, Maki, and Isozaki all worked in Tange's office, known as ARTEC.

Since the nineteenth century, the discourse of modern architecture has intersected with a series of scientific paradigms: after the mechanical model advanced by the CIAM old guard came the organismic model promoted by Team X, followed by the cybernetic, or neomechanical, model adopted by Friedman and the Metabolists. This passage from one model to the next parallels Baudrillard's account of the "orders of simulacra" from the classical world of clockwork mechanisms and automatons to the modern age of the genetic code: "It is in effect in the genetic code that the 'genesis of simulacra' today finds its most accomplished form."16 Baudrillard's account is by no means a simple history of scientific models; rather, it is an analytical chronicle of power and knowledge, much like Michel Foucault's The Order of Things. The first stage of simulacra identified by Baudrillard corresponds with the classical system of representation, in which the sovereign difference between the original and the model, the living and the nonliving, remains intact, "as in the case of that perfect automaton that the impersonator's jerky movements on stage imitate; so that at least, even if the roles were reversed, no confusion would be possible."17 The second stage corresponds with the modern age of serial, or assembly-line, production; and the third, with the postmodern age of the simulacrum, in which the original and the copy "resemble each other so closely that they no longer resemble each other at all."18 According to this scheme, the Athens Charter, as "the counterfeit of life," would belong to the first order of simulacra. The megastructure, however, aspires to a phantasmatic equivalence,19 and thus plays out the paradoxical logic of the third order. While it is one thing to compare life to the functioning of a cybernetic mechanism (of which the unity of life remains a transcendental and unattainable ideal), it is another to then equate the two, as if the terms of the analogy were reversible.

____________

16. Jean Baudrillard, "The Orders of Simulacra," in idem, Simulations, trans. P. Foss, P. Patton, and P. Beitchman (New York: Semiotext, 1983): 104; orig. pub. in L'Echange symbolique et la mort (Paris: Gallimard, 1976).

17. Ibid.: 94.

18. Rex Butler, Jean Baudrillard: The Defence of the Real (London: Sage Publications, 1999): 35; see also Sara Schoonmaker, "Capitalism and the Code," in Douglas Kellner, ed., Baudrillard: A Critical Reader (Oxford; Basil Blackwell, 1994): 170: "[The epitome of the simulacrum is the digital code] that translates all questions and answers, all of reality, into a binary opposition between zero and one. In the stage of simulation, objects are not merely reproduced through mechanical techniques. They are originally conceived in terms of their reproducibility, using a binary code."

19. The Metabolists declared: "We are not going to accept the [city] as a natural historical process, but we are trying to encourage active metabolic development of our society through our proposals." Metabolism 1960: Proposals for the New Urbanism (Tokyo: Bijutu Syuppan Sha, 1960): 1.

As we have noted, the first megastructures by Friedman and the Metabolists emerged out of discussions with Team X on how a city might grow and adapt itself to future change as if it were a living organism. Unlike Team X, however, it was not enough for Friedman and the Metabolists to develop clusters of spatial arrangements, "akin to patterns of crystal formations or biological divisions."20 The units within "the total cluster" also had to be mobile in order to allow for variability, similar to "the constant metabolism of cells." "When it comes to method," Tange wrote in 1960, "I believe we can take a hint from the various approaches in the modern sciences. One science is the study of life; the other, that of physics or mathematics. The principle of life has not yet been discovered, but organisms can be viewed macros copie ally as stable structures composed of orderly arrangements of cells. The organism lives, however, because of the constant metabolism of the cells, and this most be examined microscopically."21 This description of the organism as a "stable structure composed of orderly arrangements" forms the basis of Metabolist Fumihiko Maki's famous definition of the megastructure as a large framework containing mobile parts.22

____________

20. James Stirling, "Regionalism and Modern Architecture", Architect's Year Book 8 (1957); quoted in Fumihiko Maki, Investigations in Collective Form (St. Louis: Washington University, 1964): 11.

21. Kenzo Tange, "Technology and Humanity: From the Stenographic Record of a Speech at the World Design Conference in Tokyo, May 1960," Japan Architect (October 1960): 12.

22. Maki, Investigations in Collective Form: 8.

Maki's definition forms just one half of the living-city problematic. What is missing from this definition is the megastructure's DNA. For Friedman and his GEAM colleagues, the megastructure was analogous to cellular growth, as defined by molecular biologists, not only in terms of form, pattern, and structure but also in terms of the ordering of a finite number of elements. As the GEAM member Eckhard Schulze-Fielitz wrote in 1960: "The space structure [or megastructure] is a macro-material capable of modulation, analogous to an intellectual model in physics, according to which the wealth of phenomena can be reduced to a few elementary particles."23 Throughout the 1960s, Friedman devised computerlike programs for generating complex spatial patterns out of a taxonomy of dements and simple "rules of composition."24 In his Flatwriter project, presented at Expo 1970 in Osaka, for example, hypothetical inhabitants could generate the design of their individual living arrangements by selecting options from a keyboard of fifty-three architectural elements (floors, walls, plug-in components, and so on), combined according to the elementary rules of a computer program.25

____________

23. Eckhard Schulze-Fielitz, "The Space City," in Ulrich Conrads, ed., Programs and Manifestoes on 20th-Century Architecture (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1997): 175.

24. Yona Friedman, "L'Urbanisme comme système compréhensible," Revue Technique du Bâtiment (1964): 7–18.

25. Yona Friedman, Toward a Scientific Architecture, trans. C. Lang (Cambridge, Mass.; MIT Press, 1970).

We might easily criticize Friedman's project for taking literally what is ultimately a metaphor for life, but it is also the very literalness of the project that highlights the paradox of representation that Baudrillard raised in relation to a model approximating life so closely that it no longer resembles it at all. In the attempt to create the living city out of an a priori perception, the megastructure became what Baudrillard called "the new operational configuration" of algorithms, binary oppositions, and combinatory theories.26 Such was Baudrillard's own assessment of a late, yet celebrated, megastructure built in the 1970s: the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris, also known as the Beaubourg, by the architects Renzo Piano and Richard Rogers. In his 1977 essay, "The Beaubourg Effect," Baudrillard aptly referred to this remarkable building as an enigmatic "carcass [of] networks and circuits—the final impulse to translate a structure that no longer has a name."27 For Baudrillard, the discourse of science was predicated on a phantasmatic perception of life that treats the metaphor as substantively the same as reality. The paradox lay in the fact that all of objective reality is predicated on an operational image that does not represent anything in and of itself.28

____________

26. Baudrillard, "Orders of Simulacra": 103.

27. lean Baudrillard, "The Beaubourg Effect,” in idem, Simulacra and Simulation, trans. Sheila Glaser (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1994): 61.

28. Here, Baudrillard's theory comes close to that of psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan. As Lacanian theorist Slavoj Zizek has written: "Reality is never directly 'itself,' it presents itself only via its incomplete-failed symbolization." See Slavoj Zizek, ed., "Introduction," in Mapping Ideology (New York: Verso Books, 1994): 2.

UTOPIA AS FETISH

From 1966 to 1973, Baudrillard belonged to Utopie, an interdisciplinary group committed to the revolutionary transformation of everyday life.29 Inspired by the urban theories of the French Marxist philosopher Henri Lefebvre and by the avant-garde practices of the Situationist International (SI), Utopie sought to define architecture as a radical form of social practice.30 Since the architects of Utopie—Jean Aubert, Jean-Paul Jungmann and Antoine Stinco—were graduates of the École des Beaux-Arts, where they trained under Friedman's GEAM colleague, David Georges Emmerich, Utopie's experiments in architecture recalled the mobile structures of Friedman and the Metabolists. They proposed mobile environments and inflatable structures as a means of enacting Lefebvre's celebration of the festival of everyday life. As Stinco explained: "The inflatable represented ... a festive symbol of the new energy. It did so through its fragility, its will to express the ideas of lightness, mobility, and obsolescence, through a joyous critique of gravity, boredom with the world, and of the contemporary form of urbanism that had been realized."31

____________

29. Utopie included the urbanist Hubert Tonka; the landscape architect and feminist Isabelle Auricoste; architects Jean Aubert, Jean-Paul Jungmann, and Antoine Stinco, and sociologists Jean Baudrillard and René Lourau. See Jean-Louis Violeau, "Utopie: In Acts," in Marc Dessauce, ed., The Inflatable Moment (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1999): 37.

30. For an account of the Situationist International group and its involvement with architecture, see Mark Wigley, Constant's New Babylon: The Hyper-Architecture of Desire (Rotterdam; 010 Publishers, 1998).

31. Antoine Stinco, "Boredom, School, Utopie," in Dessauce, Inflatable Moment: 70.

This portrait of the megastructure as a freewheeling utopia typifies visionary architecture in the 1960s;32 Megastructural themes borrowed from Friedman, the Metabolists, and other first-generation megastructuralists inspired everything from Archigram's playful designs for plug-in, clip-on, and moving cities to Archizoom's variable and multifunctional furniture interiors. It was also a vision that differed from Team X's agenda to ameliorate, rather than overturn, the existing social condition. For Utopie, the unity of life was not so much an aesthetic and technological problem, as it was a social and political strategy. But if, for the architects of Utopie, "mobility and the interconnectedness between space and function it allows" were the ingredients of a new leisure society liberated from work habits and constraints, for Baudrillard, these qualities did not necessarily amount to a revolutionary position, nor did they even challenge the status quo.33 In the first issue of Utopie's eponymous magazine, Baudrillard observed: "Ephemera might one day be the collective solution, but for now it is the monopoly of a privileged few.... This is not to disqualify the formal research of the architect, but there is bitter derision in the fact that this research for a social rationale ends up reinforcing the irrational logic and strategy of the class cultural system."34 From the beginning, then, Utopie's attempt to reconcile visionary architecture with radical criticism was a difficult, if not impossible, proposition, as if the very thing to which Utopie aspired had been foreclosed in advance.

____________

32. Jean-Paul Jungmann described the scene: "The 1960's produced a lot of theoretical works, and numerous groups emerged, including the Metabolists in Japan, Superstudio in Italy, Archigram in England, Haus-Rücker in Austria, and others. New concepts—ephemerality, mobility, the 'total city,' composition through accumulation—had a strong appeal, and were associated with the invention of new designs inspired by the industrial object, the machine, space and submarine capsules, the connivance with pop art, cartoons, etc." Dessauce, Inflatable Moment: 66–67.

33. Butler, Jean Baudrillard: 32.

34. Jean Baudrillard, in Utopie 1 (May 1967): 96–97: “L'éphémere sera peut-être un jour la solution collective, mais pour l'instant il est le monopole d’une fraction privilégiée... Ceci n'est pas du tout pour disqualifier la recherche formelle de l’architecte: mais il y a une amère dérision dans le fait que cette recherche d'une rationalité sociale aboutisse précisément à renforcer la Logique irrationnelle et la stratégie du système cultured de classe.“

In its statement, "La Logique de l'urbanisme" (1967), Utopie argued that as long as the science of urbanism participated in the capitalist logic of production, it could never attain what it had set out to realize: "the totality of the urban."35 "In synthesizing," Utopie argued, "the urbanist thinks he is making the unity of the city legible, when in fact he is doing nothing but projecting his own representation of the city, inherited from the cultural and advertising ideology of contemporary society, onto the urban reality."36 In other words, for Utopie, modern planning projected an image of the urban not as it really was, but as the urban scientist imagined it "through the rationale of his own creations (development plans, schemas of structure, rules, and so on)."37 Initially, this critique was aimed at the bleak new housing estates of the urban peripheries, thus concurring with Team X's own misgivings about the functionalist precepts of CIAM, But if the megastructure had once seemed like a promising alternative, it would not take long for Utopie to turn its Marxist position against its own projects. In May 1968, student radicals satirized visionary architecture with slogans such as: "Are we fighting for inflatables?"38 And in the following year, Utopie, in turn, denounced the very architecture it originally embraced at a 1969 conference in Turin called "Utopia e/o Rivoluzione."39 There, Utopie effectively announced the end of the megastructure movement: "Mobile cities, cities on the move, sweet 'software' the end of misery, the technology of everything, the lucid 'gadget', the city of lights, the technology of the Concorde, the Gemini program, the soft revolution ... and during all this time, nothing of this in everyday life. ... In a subtle dialectic between the possible, which will never be, and the false utopian conscience, overwhelmed with marvels, the vicious circle completes itself in an attempt to conceal radical criticism from the world of production. ... Utopia is a luxury good, blinding us with its splendor."40

____________

35. Utopie, "La Logique de l'urbanisme," Utopie 1 (1967): 4.

36. Ibid.: 5: "En synthétisant, l'urbaniste pense rendre lisible l'unité de la ville, et la lire. Il ne fait rien d'autre que projeter sa propre répresentation de la ville, héritière de l’idéologie culturelle et publictaire de la société contemporaine, sur la réalité urbaine."

37. Ibid.: "par la rationnalité de ses créations (plans d’aménagement, schémas de structure, réglements...)."

38. Quoted in Jean-Louis Violeau, "Interview," Utopie 2 (May 1968): 50.

39. The conference was organized by junior faculty members in the department of architecture at the Turin Polytechnic: Giorgio Ceretti, Grazieila Derossi, Pietro Derossi, Adriana Ferroni, Aimaro Oreglia d'Isola, Riccardo Rosso, and Elena Tamagno. The invited participants were Romaldo Giurgola, Paolo Soleri, Architecture Principe, Archigram, Yona Friedman, Utopie, and Archizoom.

40. Utopie, Utopia e/o Rivoluzione (Turin: Editrice Magma, 1969): 34: "Le città mobili, le città che si spostano, la dolce ‘software’, la fine della miseria, la tecnica-che-puo-tutto, il ludico nei ‘gadget’, le luci della città, la tecnica dal Concorde, la tecnica del Gemini, la rivoluzione in dolcezza... e per tutto questo tempo nella vita quotidiana, niente di tutto questo. ... In una sottile dialettica tra il possibile che non sarà e la falsa coscienza utopica che si circonda di meraviglioso, si compie il circolo vizioso che tenta di far sparire dal mondo della produzione la critica radicale. ... L'utopia è una merce di lusso, dallo splendore accecante."

"La Logique de l'urbanisme," Utopie's pre-1968 manifesto, had extended Marx's analysis of the commodity-fetish to the problem of urbanism. Following Marx, who defined the commodity-fetish as the imaginary equivalent of an object whose value is but the reflection of a network of market relations (supply and demand), Utopie argued that the science of urbanism enacted the "diabolical substitution" of the territory with the commodity-sign.41 After May 1968, however, things became more complicated, and "the totality of the urban" was not just a false representation masking the actual state of things, but rather, a "tactical illusion," an alibi, masking a constitutive impossibility. "An important contradiction in the [capitalist] system," Utopie wrote, "consists in the fact that technological progress is supposed to liberate the working class, thanks to the reduction or elimination of work. This liberation in technology inspires most of the current formalizations of utopia, but the realization of automation is impossible in a bourgeois world, since only the fulfillment of human labor can generate the reproduction of surplus value. The spectacle ... makes possible the illusion that the end of misery is near."42 Paradoxically, then, the surplus value required to bring about the end of work is also the very impediment that undermines the potential of technology to liberate human beings from the drudgery of work.

____________

41. Lourau, "Contours d'une pensée critique nommé urbanisme": 10.

42. Utopie, Utopia e/o Rivoluzione: 33–34: "Una importante conttadizzione del sistema sta ne! fatto che lo sviluppo delle forze produttive legato al progressa tecnolgico, conduce normalmente a una liberazione sempre maggiore dei lavoratori dovuta alla diminuzione o all'annullamento dei tempi di lavoro. Questa liberazione technologica ispira la maggior parte della formalizzione utopiche contemporanee, ma la realizzazione dell'automazione è impossibile in un mondo borghese, poiché solo l'espletamento del lavoro umano permette la riproduzione del plus-valore, fondamento del sistema. Solamente lo spettacola, offerto dai settori tecnologicamenti avanzati, che suffragano l'immaginario della nostra società, permette di dare l'illusione che la fine della miseria sia prossima."

This paradoxical logic of the commodity-fetish also underlies Baudrillard's concept of the simulacrum as a paradoxical element that incarnates the ideal only insofar as it does not represent anything in and of itself (it is the mirror-image of a network of social relations), and from which it follows that the logical culmination of a given system is also its internal limit. In Baudrillard's post-1968 essays, this paradox applied not only to capitalism but to all systems of rationality. In "The Precession of Simulacra," for example, Baudrillard wrote: "The cartographer's mad project of an ideal coextensivity between the map and the territory, disappears with simulation—whose operation is nuclear and genetic, and no longer specular and discursive. ... No more imaginary coextensivity: rather, genetic miniaturization is the dimension of simulation."43 For Baudrillard, molecular biology constituted a discourse that was predicated on the "tactical" substitution of a metaphor of life for the real thing itself. In quoting Jacques Monod, the Nobel laureate who once speculated that "the human organism had a cybernetic feedback system controlling its chemical processes,"44 Baudrillard noted, "Monod very well expresses the arbitrary nature of this phenomenon: 'We might wonder if all the invariance, conservations and symmetries that constitute the scheme of scientific discourse are only fictions substituted for reality so as to offer an operational image ... a logic founded on a purely abstract principle of identity possibly conventional. Convention, however, that human reason seems incapable of doing without.'"45

____________

43. Jean Baudrillard, "The Precession of Simulacra," in idem, Simulations: 3; orig. pub. in Traverses 10 (1978).

44. Hughes and Hughes, "Introduction," in idem, Systems, Experts, and Computers: 21.

45. Baudrillard, ''Orders of Simulacra": 113.

By extending Marx's analysis of the commodity-fetish to a theoretical understanding of phenomena outside the field of political economy, Baudrillard put into question the ideals of freedom, rationality, and human progress that had formerly guided revolutionary practice, including the Marxist ideology of scientific socialism.46 While, throughout its writings, Utopie held on to the prospect of utopia, even though this could not be positively defined, Baudrillard's essays from the mid-1970s abandoned this perspective altogether. The turning point, as Baudrillard himself pointed out in "The Beaubourg Effect," was the failure of the May 1968 revolution. Far from representing a capitulation to the status quo, however, Baudrillard's concept of the simulacrum was an attempt to highlight the paradox that makes social reality both possible and impossible.47 "Certainly, since 1968," he wrote, "the social, like the desert grows—participation, management, generalized self-management, etc.—but at the same time it comes close in multiple places, more numerous than in 1968, to its disaffection and to its total reversion."48 Ironically, the inflatable structure bore witness to such a gesture, since its very form expressed the paradoxical fullness/emptiness of the bourgeois ideology Utopie critiqued.

____________

46. Butler, Jean Baudrillard: 7.

47. Baudrillard, "Beaubourg Effect": 73.

48. Ibid.

URBAN FICTION

In 1972, the British architectural historian, Reyner Banham, announced the fate of modern architecture's latest incarnation at a talk he gave in Naples: "The megastructure is dead, and thus the time has come to write its history."49 The outcome of this pronouncement was Banham's 1976 survey, Megastructure: Urban Futures of the Recent Past. Although Banham had been a champion of the megastructure since its beginnings in the late 1950s and actively promoted architects, such as the Smithsons and Archigram, in the early 1970s, he began to question the megastructure's continuing viability as a new model of urbanism. As Banham stated in a 1974 lecture at the Artnet in London, an architectural forum organized by Peter Cook: "At a remove of ten years, to design in that way appears to have become inconceivable. Is it simply because our own view of what is permissible has changed? It is already difficult to reconstruct the mood of 1964, the mood which made the megastructure parts of the Buchanan Report [on traffic] conceivable and perfectly acceptable to the average British Town Counciller and Deputy Planning Officer. What were we all up to in 1964? Because I do not think any of us found this kind of project very shocking as we do now."50

____________

49. Reyner Banham, quoted in "Banham: La Megastrutture é Morta," Casabella, no. 375 (1972): 2.

50. Reyner Banham, Recorded lecture, Artnet, London, October 15, 1974, videotape, Architectural Association, London.

For Banham, what had begun as a critique and promising alternative to the academic phase of CIAM modernism had devolved, in its turn, into another "academicism of the avant-garde." As the ideas of Team X and the Metabolists gained widespread acceptance from the architectural establishment, mainstream megastructures, such as the multilevel roadway system proposed by the architect Colin Buchanan for the British Ministry of Transportation and Paul Rudolph's Lower Manhattan Expressway project of 1967–72 (page 71), which graced the cover of Banham's book, were increasingly associated with the dubious "science" of futurology and, as Banhanr put it, with the prognostications of "the Hudson Institute and RAND Corporation on a sunny day."51 According to Banham, the tide of acceptance among megastructuralists themselves began to change in 1968 "when the Left finally began to mount cogent criticism of [the| mega-structure . . . with arguments that. . . derive[d] from the neo-Marxism of Herbert Marcuse, maintaining that the permissive freedoms offered by [the] megastructure's adaptability and internal transiences were illusory, since all they involved were choices between fixed alternatives prescribed by the designers of the megasystem, and were thus as meaningless as the consumers' supposed choices between different products offered by the capitalist system's supermarkets."52 "This critique," Banham noted, "did not come, to the best of my knowledge, from anywhere in the established and organized Left, but was put to me, appropriately enough, by dissident students on the second night of the événements de Mai."53

____________

51. Reyner Banham, Recorded lecture, Artnet, London, October 2, 1974, videotape, Architectural Association, London.

52. Banham, Megastructure: 206.

53. Ibid.

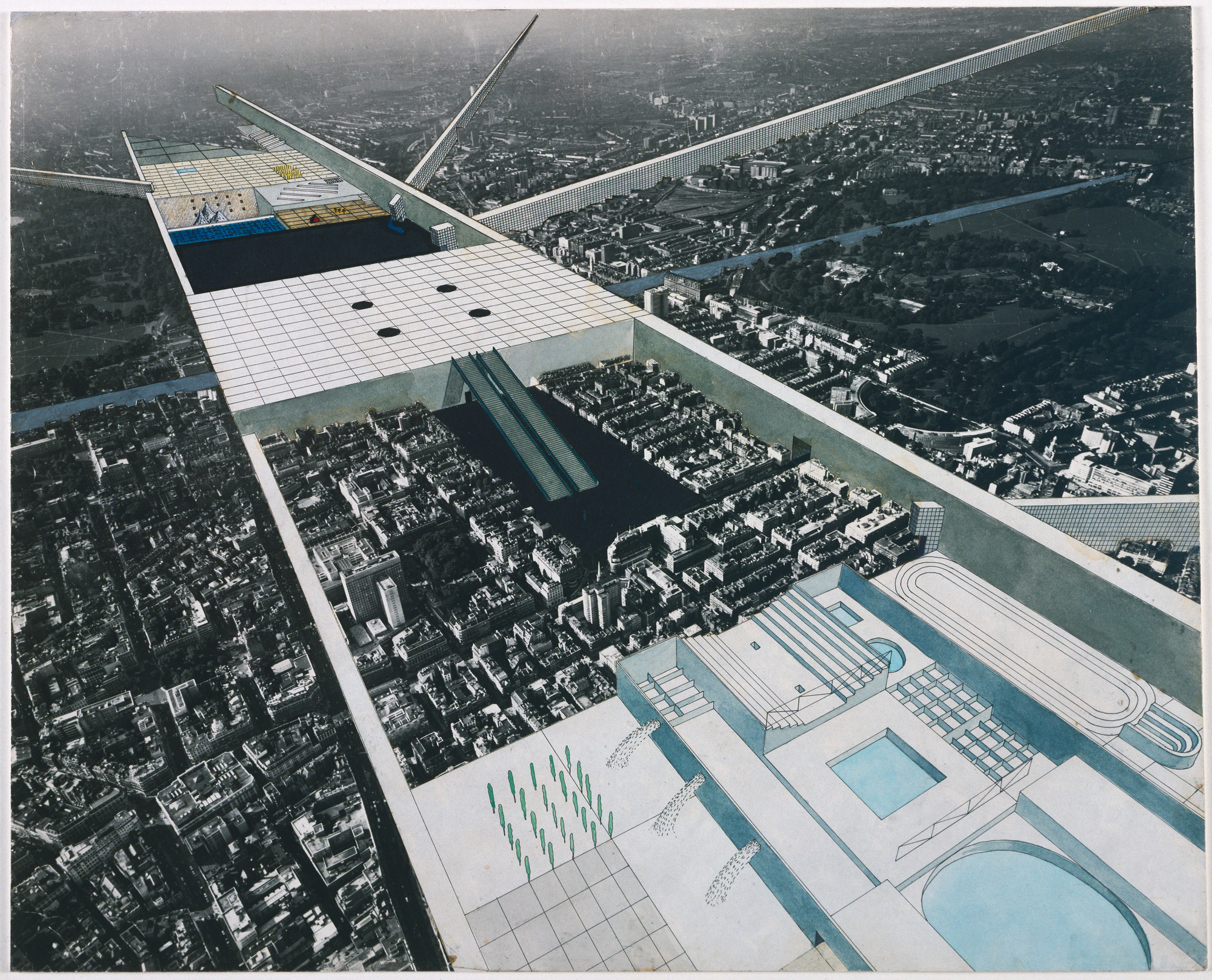

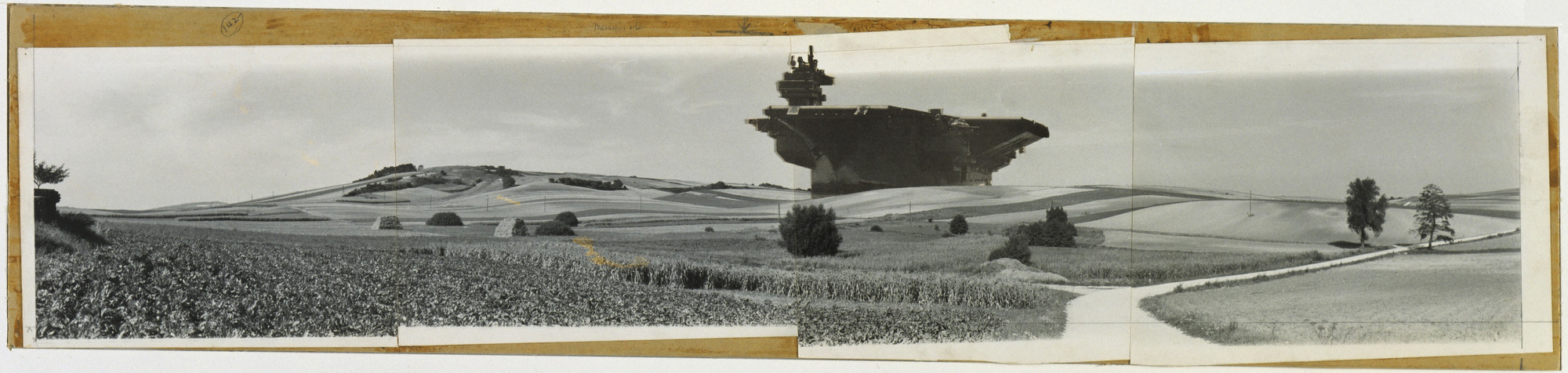

Figure 3. Hans Hollein. Aircraft Carrier City in Landscape. Project, 1964. Perspective: cut-and-pasted reproduction on four-part gelatin silver photograph mounted on hoard, 8½×39⅜" (21.16×100 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Philip Johnson Fund

Banham, of course, was not the only architectural historian to toll the death knell of the megastructure. Among others, the Italian historian and critic, Manfredi Tafuri also denounced the megastructure in his Theories and History of Architecture (1969), thereby retracting his previous statements of the early 1960s in support of the movement.54 His remarks in 1969 were as grave as those of Utopie, since, for him, radical criticism meant that architecture, like the mass media, was always already implicated in the production of power: "If, today, architecture is not able to call anyone to freedom, if its own freedom is illusory, if all its petitions sink in a quagmire of 'images' at best amusing, there is no reason why one should not take up a position of determined contestation towards architecture itself, as well as towards the general context that conditions existence."55

____________

54. Giorgio Piccinato, Vieri Quilci, and Manfredo Tafuri, "La città territorio: verso una nuova dimensione," Casabella, no. 270 (December 1962): 16–19.

55. Manfredo Tafuri, Theories and History of Architecture, trans. Giorgio Verrechia (London: Granada, 1980]: 236.

In response to such criticisms, visionary architects began to reposition themselves against the megastructure and monumental image making. Archigram opted for small-scale urban interventions and "invisible" networks in projects such as David Greene's electric garden of delights: Logplug, Rokplug, and L.A.W.U.N. (Locally Available World Unseen Networks, 1969); Paul Virilio of Architecture Principe abandoned his experiments with space and architecture and devoted himself entirely to theory, writing brilliant and provocative essays on the impact of military technologies on everyday life.56 Austrian visionaries, such as Walter Pichler (pages 136–139), Raimund Abraham (pages 116, 117), and Friedrich St. Florian (page 127), turned inward, producing poetic dreamscapes at the more personal scale of the house. Hans Hollein (figure 3), Léon Krier (pages 103–105, 118, 129), and other onetime megastructuralists joined the burgeoning postmodern movement, in which the entire history of architecture was treated as a vast repertory of symbols to be endlessly mined, manipulated, and collaged. Among other things, postmodernism replaced the utopian narratives of the modern movement with a pluralist approach that equated architectural production with the syntax and grammar of a free-floating language.57 In so doing, however, it also rendered architecture socially and politically mute. As Tafuri (an ambivalent critic of postmodernism) put it: "In place of an anxious effort to restructure the urban system, there is a disenchanted acceptance of reality [and its takeover by the sign], bordering on extreme cynicism."58

____________

56. When Paul Virilio was asked by Enrique Limon what impact the political events of May 1968 had on his work, he replied: "During the sixties I was working on geopolitics, on geometry, on actual space, on topology etc. In '68 I realised that one could not interfere with space without taking power. So I dropped the issue of space completely to focus on topics like time, speed, dromometry, which have been the center of my work for the last thirty years. Groupe Architecture Principe was about space and politics whereas the issue of speed is about time and politics, which opens a whole new vista of research. All the relevant documents will be republished next year for the thirtieth anniversary of Groupe Architecture Principe. But for me, that was a kid's game. It's over. I was 35. Today l am 64. It's a long time, thirty years." See Paul VLrilio, quoted in Stan Allen and Kyong Park, eds., "Paul Virilio and the Oblique," in Sites & Stations: Provisional Utopias, (New York: Lusitania Press, 1996): 184.

57. Krier's work might be considered modern in content and postmodern in form. In rejecting the utopian aims of modern architecture, he seems to have erected another utopian fantasy in its place—this time, a nostalgic utopia set in the pre-industrial past.

58. Manfredo Tafuri, "L'Architecture dans le boudoir," in idem, The Sphere in the Labyrinth: Avant-gardes and Architecture from Piranesi to the 1970s, trans. Pellegrino d'Acierno and Robert Connolly (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1990): 286.

An important exception to this postmodern turn in the aftermath of May 1968 was Superstudio, a group of young Florentine architects whose use of metaphors and rhetorical devices was a means to expose the internal limitations of a modern world colonized by the sign, rather than a postmodern surrender to it.59 Founded in 1966 by Adolfo Natalini and Cristiano Toraldo di Francia, Superstudio was one of several groups that originated out of megastructuralist Leonardo Savioli's course at the University of Florence in the 1966–67 academic year, a course on the utopian transformation of life through the use of mobile, flexible, and inflatable structures, following the work of Archigram, Utopie, and others.60 Soon after the Turin conference in April 1969 (attended by the group), Superstudio left behind its utopian convictions, producing a series of critical projects on the limits of utopia—projects that some commentators mistook as a final attempt to rehabilitate the megastructure.61 Superstudio's method was not to supersede the limits of modernism by replacing it with another fiction, but to pursue the logic of this discourse to its paradoxical conclusion. As Natalini explained in a 1983 interview with Monica Pidgeon, the editor of Architectural Design: "Many of the first projects, which are now labeled utopian and are considered part of the Italian avant-garde movement called 'Architettura Radicale,' were not meant to be utopian at all. On the contrary, they used rhetorical devices to make negative utopias, demonstratio per absurdum,"62

____________

59. This discussion of Superstudio is based on a paper I presented at the Society of Architectural Historians in Houston, Texas, in April 1999.

60. The core members of the group were Aldolfo Natalini, Cristiano Toraldo di Francia, Roberto Magris, Alessandro Magris, and Piero Frassinelli. Alessandro Poli joined the group between 1970 and 1972. In 1966, Naralini was Savioli's teaching assistant, and Poli and Roberto Magris were students in Savioli's course. Many of the students from this course formed various groups: Archizoom, Gruppo 9999, UFO, and Zziggurat. See Paola Navone and Bruno Orlandoni, Architettura "Radicale" (Milan: Documenti di Casabella, 1974): 25. On Savioli's course, see: Leonardo Ricci, ed., Ipotesi di Spazio (Florence: Giglio & Garisenda, 1972); and Leonardo Savioli and Adolfo Natalini, "Spazio di Coinvolgimento," Casabella 32, no. 326 (July 1968): 32–45.

61. Adolfo Natalini, ed., Superstudio: Storie con Figure 1966–73 (Florence: Galleria Vera Biondi, 1979): 6, 8.

62. Adolfo Natalini, interview with Monica Pidgeon, March 1983, audiocassette, Royal Institute of British Architects, London.

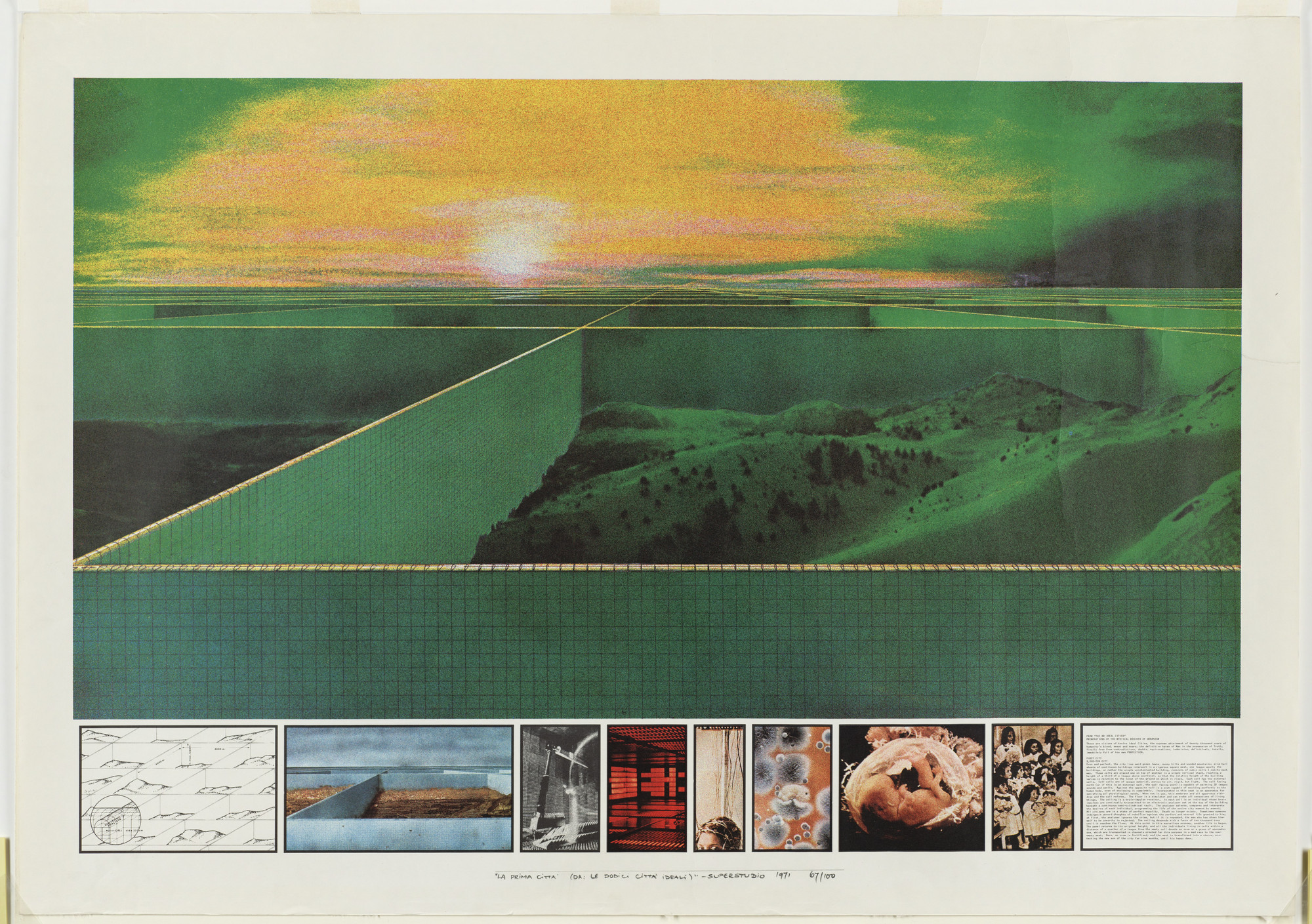

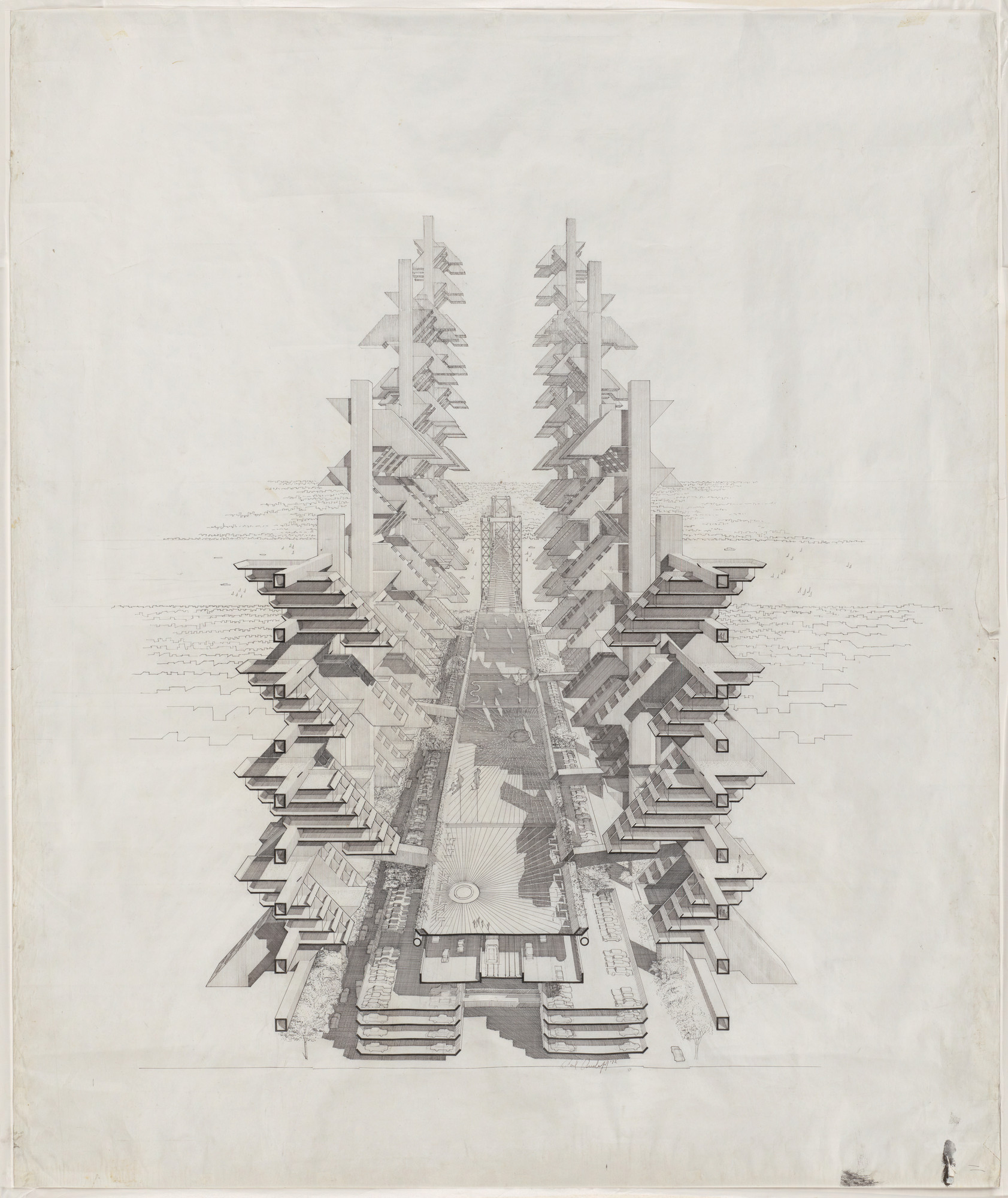

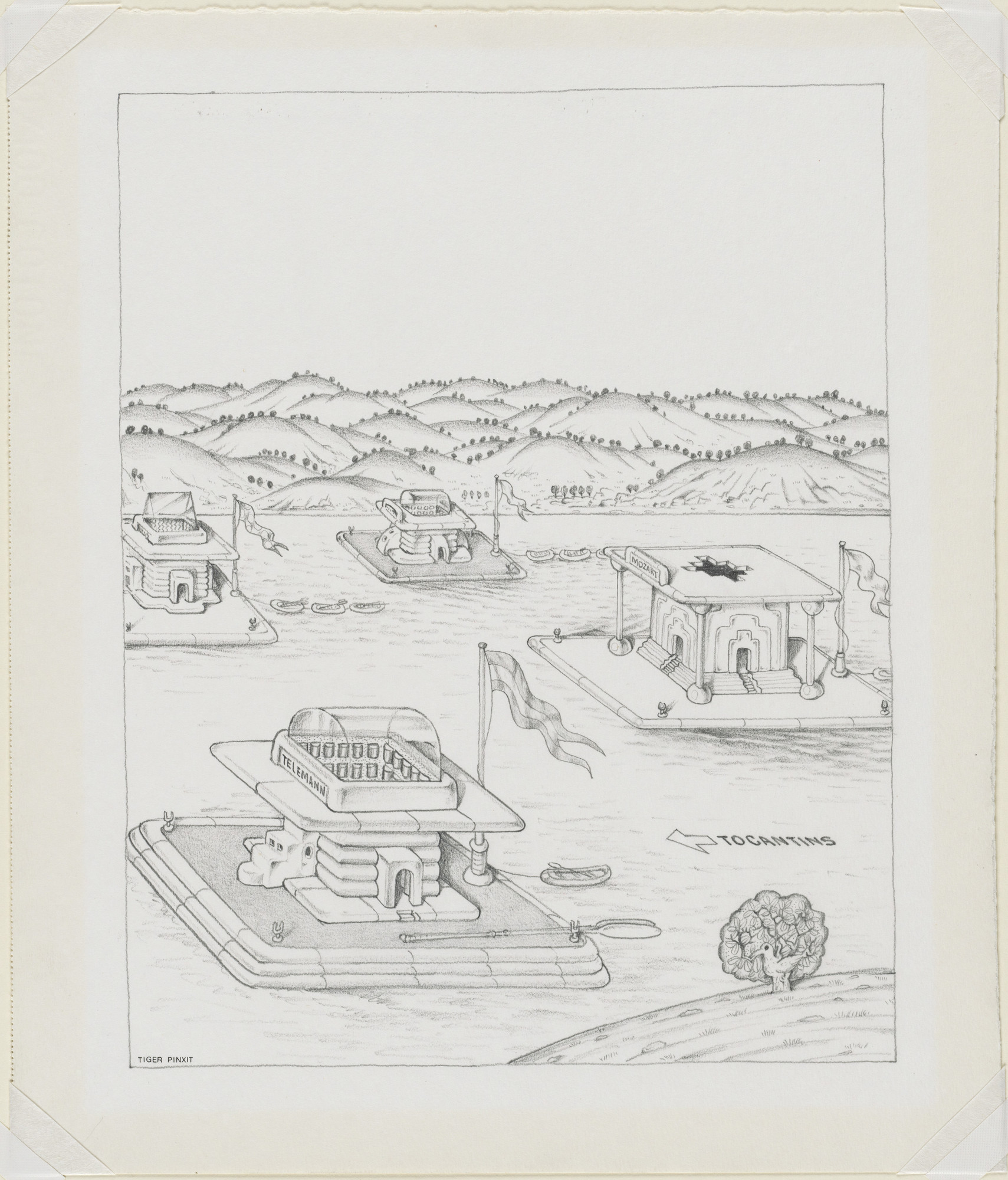

Figure 4. Supersrudio (Cristianu Toraldo di Francia, Gian Piero Frassinelli, Alessandro Magris, Roberto Magris, Adolfo Natalini). Twelve Ideal Cities: The First City. Project, 1971. Aerial perspective: photolithograph, 27¾ × 39 5/16" (70.2×1006 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Given anonymously

One such demonstratio per absurdum is Superstudio's Twelve Ideal Cities (1971), an allegory on modern utopias of the twentieth century (figure 4). The twelve cities are supposed to represent "the supreme achievement of twenty thousand years of civilization," but are in fact hallucinatory provocations, tactical illusions, as Baudrillard would have put it.63 In the 2000-Ton City, for example, we are told that the inhabitants live in cells equipped with electronic devices that can satisfy all needs and desires, but we are also told that if anyone indulges in thoughts of rebellion, the ceiling will collapse with a force of two thousand tons. In another city, a spaceship in the shape of a giant wheel on an intergenerational voyage, the crew members lie peacefully asleep in their cabins dreaming a common dream, but are periodically killed and ejected as they reach the end of a predetermined life-cycle to make way for the newly born. Each of the twelve cities promises eternal happiness and perfection, but is also flawed in some unthinkable and horrifying way. For Superstudio, the modernist utopia is not only unattainable, its pursuit is a contradiction in terms. As a 1972 text by Superstudio inquired; "Where do you think you'll end up by taking the Utopian Road? Do you really believe that this is the way out of the mistakes and the misery that surrounds us? Have you forgotten that this road is as long as the existence of man and that no one has ever found a resting-place along it? Can't you see that it is illumined by a false light; that the footsteps you can hear advancing are the sounds of dreams; that the lakes you can see from it are a mirage, a shimmering fata morgana provoked by the blinding sun?"64

____________

63. Superstudio, "Twelve Cautionary Tales for Christmas," Architectural Design (December T971); 735.

64. Superstudio, "Utopia, Antiutopia, Topia," In, no. 7 (September–October 1972): 93.

Figure 5. Rem Koolhaas and Elia Zenghelis, with Madelon Vriesendorp and Zoe Zenghelis. Exudus, or The Voluntary Prisoners of Architecture: The Strip. Project, 1972. Cut-and-pasted paper with watercolor, ink, gouache, and color pencil on gelatin silver print, 16×19⅞" (40.6×50,5 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York

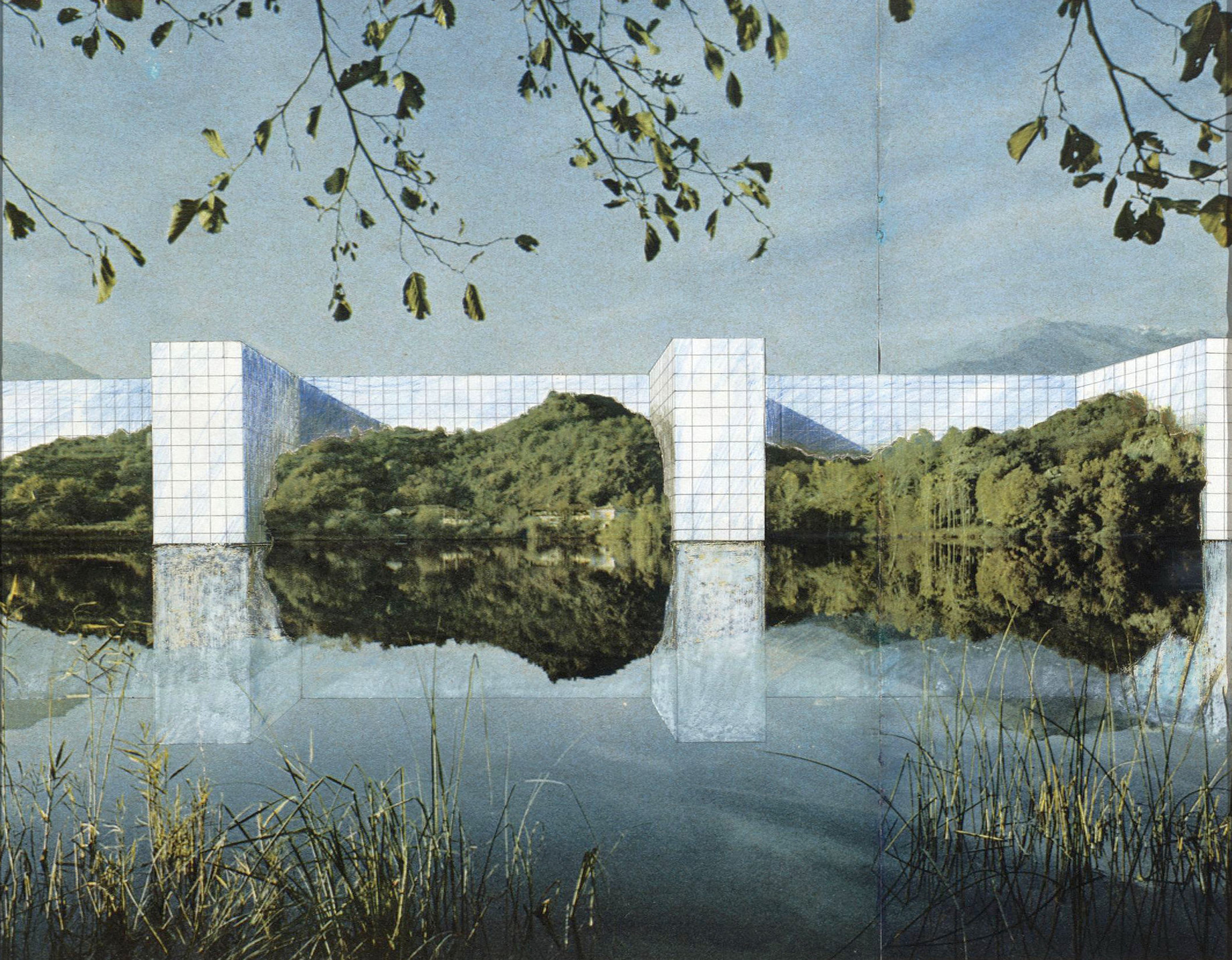

The Twelve Ideal Cities is part of a series of projects, or "didactic essays," as Natalini called them, that includes The Continuous Monument of 1969 (pages 73–77), Reflected Architecture (1971–72), and Utopia, Antiutopia, Topia (1972). Together they make a seductive proposition that draws attention to the fiction that simultaneously frames the discourse of modern architecture and prevents that discourse from forming a totalizing whole. For this reason, the most striking feature of The Continuous Monument is its hard mirrored surface, which reflects its surroundings, revealing nothing of itself.

If there is a proper coda to Superstudio's critical turn, then perhaps it would be Rem Koolhaas's Delirious New York (1978), Koolhaas's earlier (1972) project for a linear city, titled Exodus, or The Voluntary Prisoners of Architecture (figure 5) pays tribute to Superstudio's Continuous Monument.65Delirious New York, a retroactive manifesto for a modern "culture of congestion" is an attempt at defining a blueprint for architecture with a certain self-consciousness of the fictions involved. As Koolhaas noted, Le Corbusier's favorite method of translating vision into reality was reinforced concrete, an infinitely malleable substance that could harden into any shape or form. For Koolhaas, this construction method was strictly analogous to the technique Salvador Dalí proposed for realizing Mary's Ascension, which was to take a photograph of an inverted image of the Holy Virgin projected onto falling peas. "By recording [the fiction] in a medium that cannot lie," Koolhaas wrote, "that postulate is made critical—objectified ... put into the real world where it ... can become active."66

____________

65. See Dominique Rouillard, in Alain Guiheux, ed., Tschumi, une architecture en projet: Le Fresnoy. (Paris: Centre Georges Pompidou, 1993): 90–91.

65. Rem Koolhaas, Delirious New York (New York: Monacelli Press, 1994): 249.

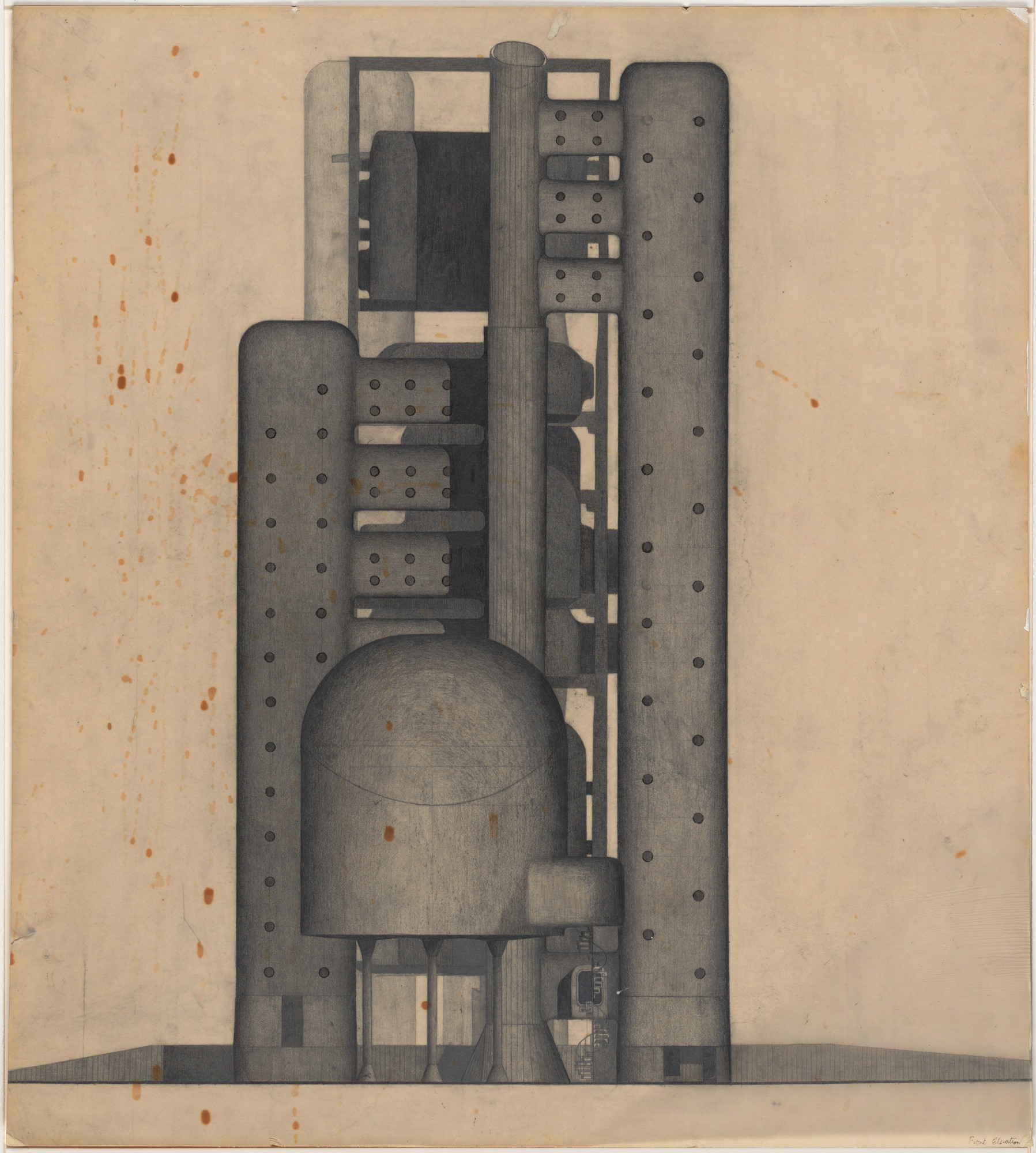

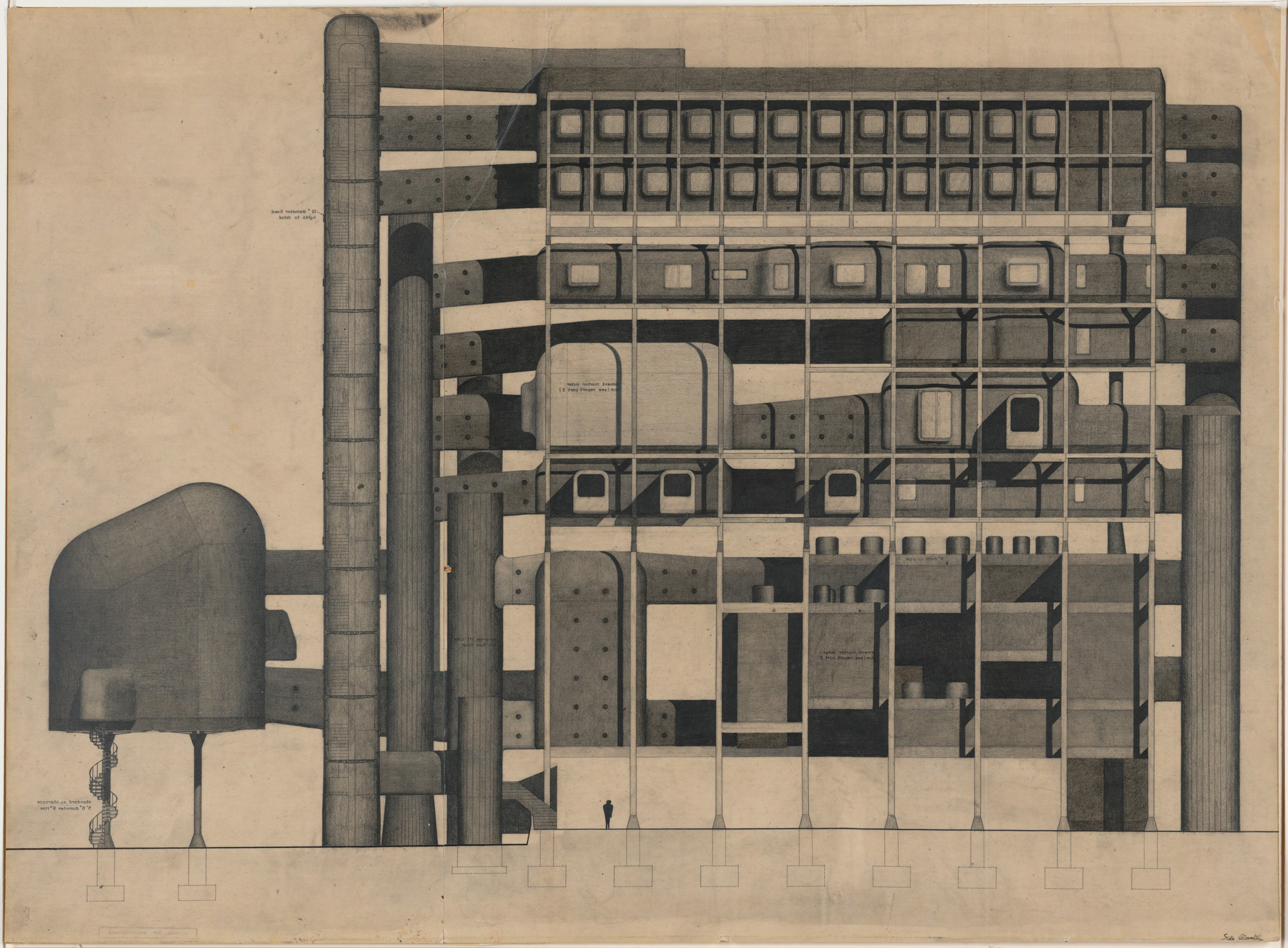

THE MEGASTRUCTUREMICHAEL WEBB (Archigram)British, born 1937

Michael Webb, a founding member of Archigram, the radical British architectural collaborative, designed the Furniture Manufacturers Association Headquarters as a fourth-year studio project at the Regent Street Polytechnic School of Architecture in London. He was influenced by the organic forms of Frederick Kiesler and John Johansen, and by the atmosphere of nonconformity prevalent among his fellow students. The unrealized biomorphic structure is divided horizontally into three different programmatic zones: the lower, a furniture showroom; the middle, administrative offices, and the top, rental office space. The bulbous form visible to the left in the side elevation was to be a freestanding lecture theater. The eminent architectural historian Nikolaus Pevsner described the project for a BBC radio audience as, "A lot of stomachs sitting together on a plate, connected by bits of gristle."

Michael Webb. Furniture Manufacturers Association Headquarters, High Wycombe, England. Project, 1957–1958. Elevation: graphite and ink on tracing paper, mounted on board, 24×21¼" (61×54 cm)

Michael Webb. Furniture Manufacturers Association Headquarters, High Wycombe, England. Project, 1957–1958. Side elevation: graphite and ink on tracing paper, mounted on board, 23½×32" (59.7×81.3 cm)

YONA FRIEDMANFrench, bom Hungary, 1923

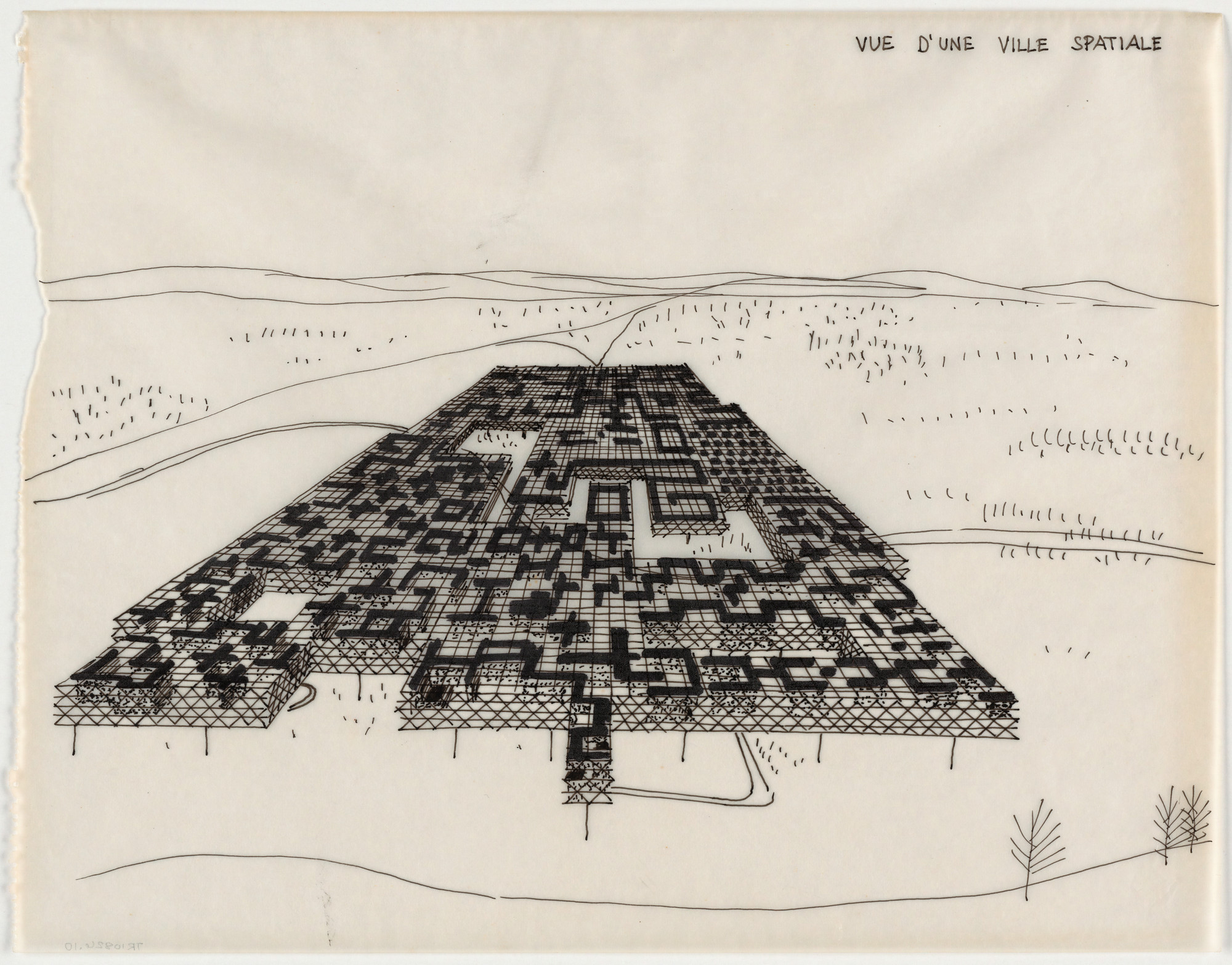

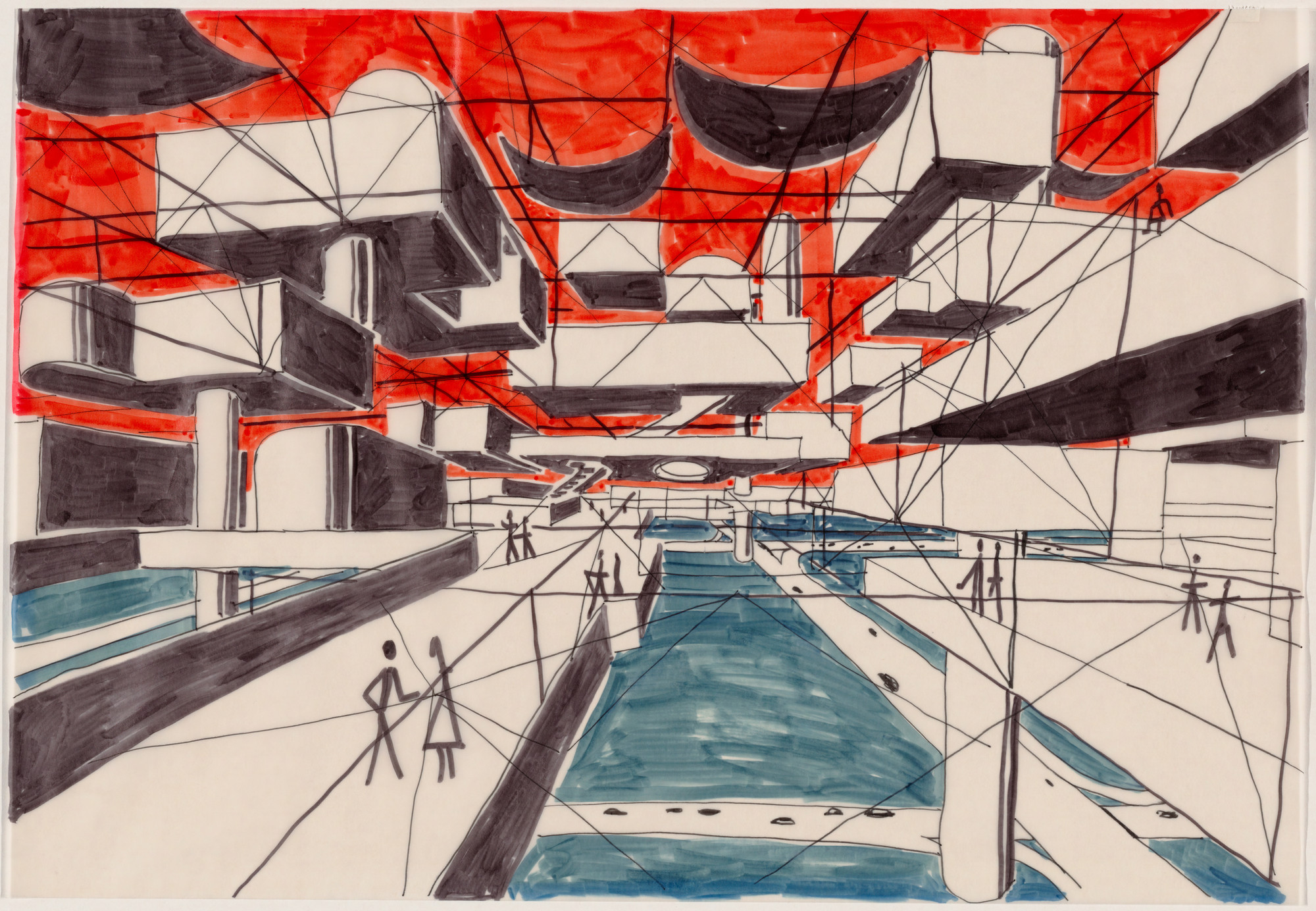

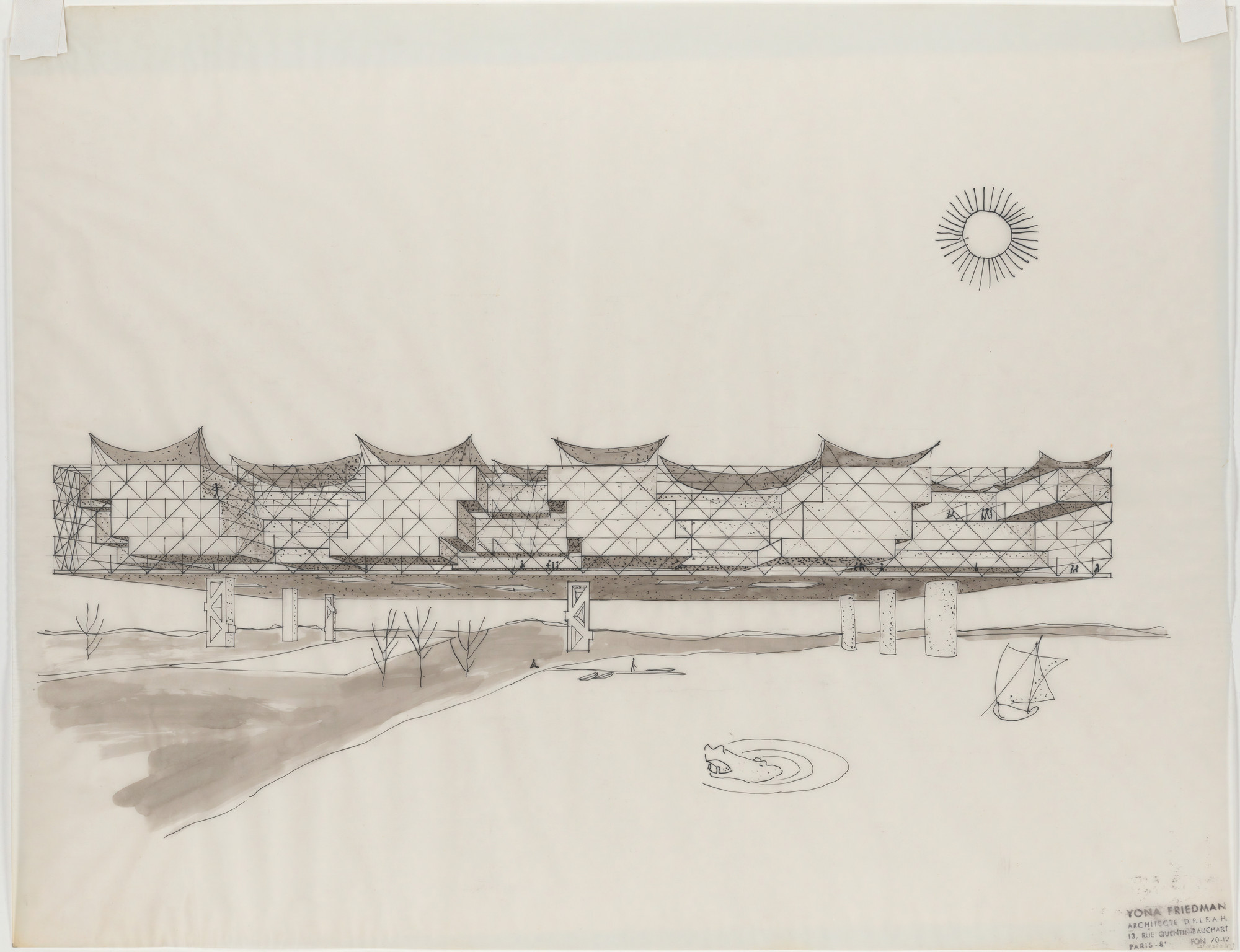

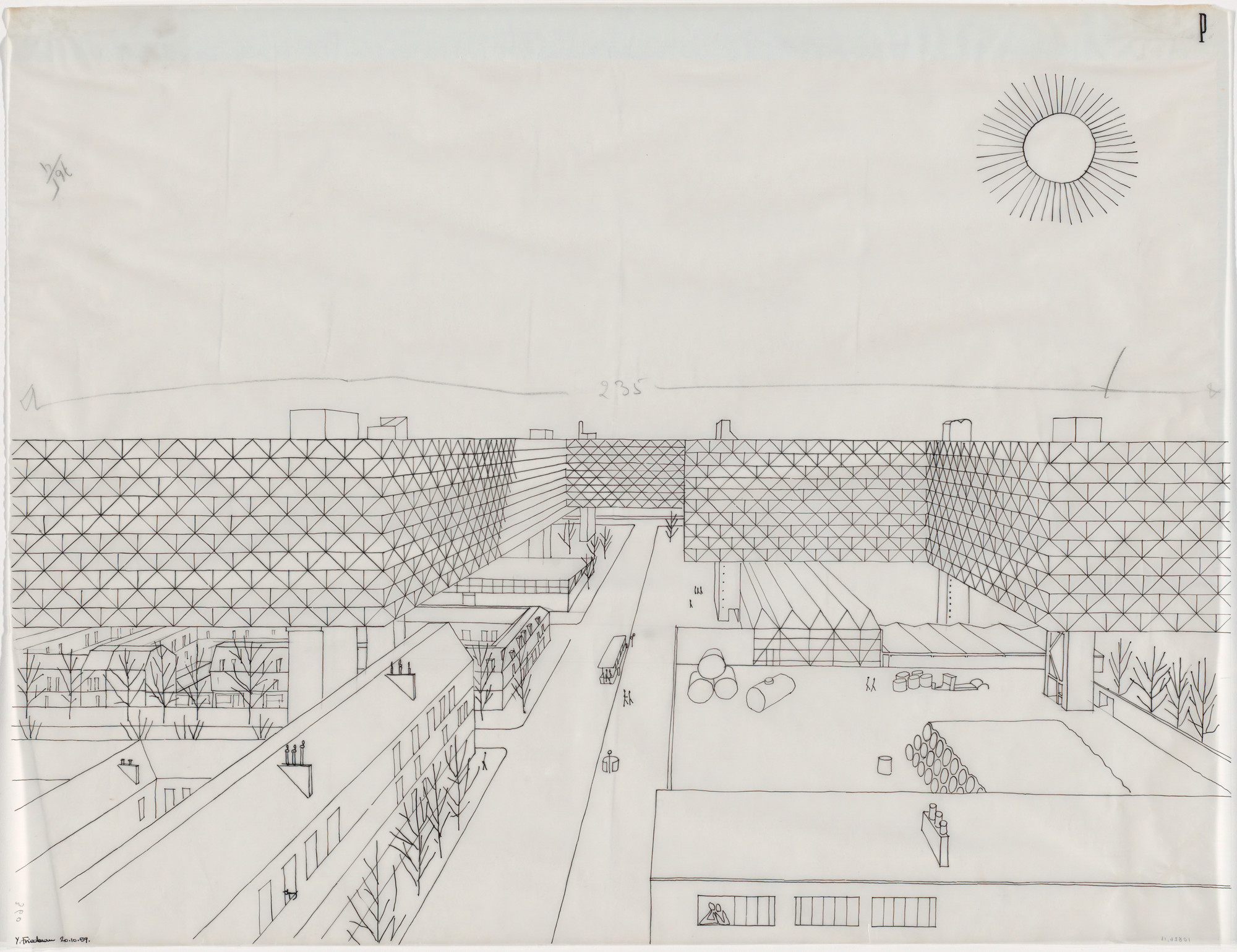

The Spatial City (Ville spatiale) is an unrealized theoretical construct inspired by the housing shortage in France during the late 1950s and by Yona Friedman's deep belief that housing plans and structures should allow for the free will of the individual inhabitants. Not wanting to displace the city below, Friedman raised a second city fifteen to twenty meters above the existing one. The framework was to be erected first, and the residences conceived and built by the inhabitants inserted into the voids of the structure. The layout of each level would occupy no more than fifty percent of the overall structure in order to provide air and light to each residence as well as to the city below. The project was designed for construction anywhere, and meant to be adapted to any climate.

Yona Friedman. Spatial City, project, Aerial perspective. 1958. Ink on tracing paper. 8⅜ × 10¾" (21.3 × 27.3 cm)

Yona Friedman. Spatial City Project (Perspective). 1958–59. Felt-tipped pen on tracing paper. 13½ × 19½" (34.3 × 49.5 cm)

Yona Friedman. African Proposals, project, Perspective. 1959. Ink and watercolor on tracing paper. 19 × 25⅜" (48.3 × 64.5 cm)

Yona Friedman. Spatial City, Elevated Blocks, project, Paris, France, Perspective. 1959. Ink and graphite on tracing paper. 19¾ × 25½" (50.2 × 64.8 cm)

Yona Friedman. Spacial City project, Centre de l'Art Moderne Project, France. 1970s. Ink on relief print. 11½ × 16⅝" (29.2 × 42.2 cm)

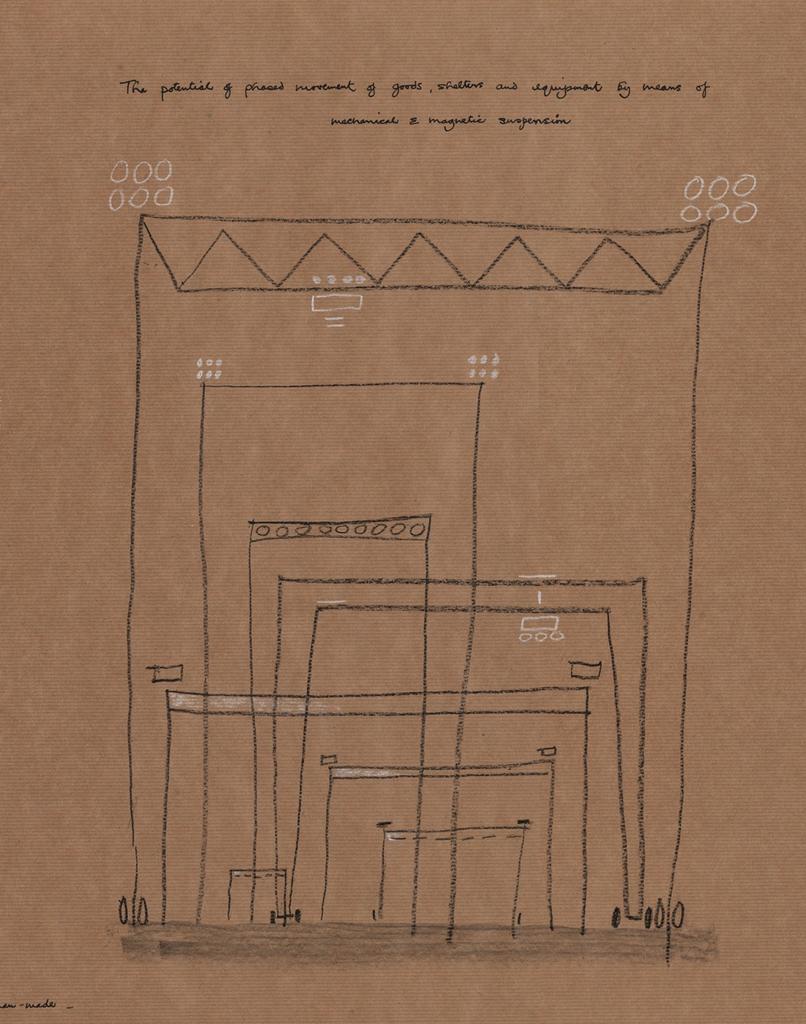

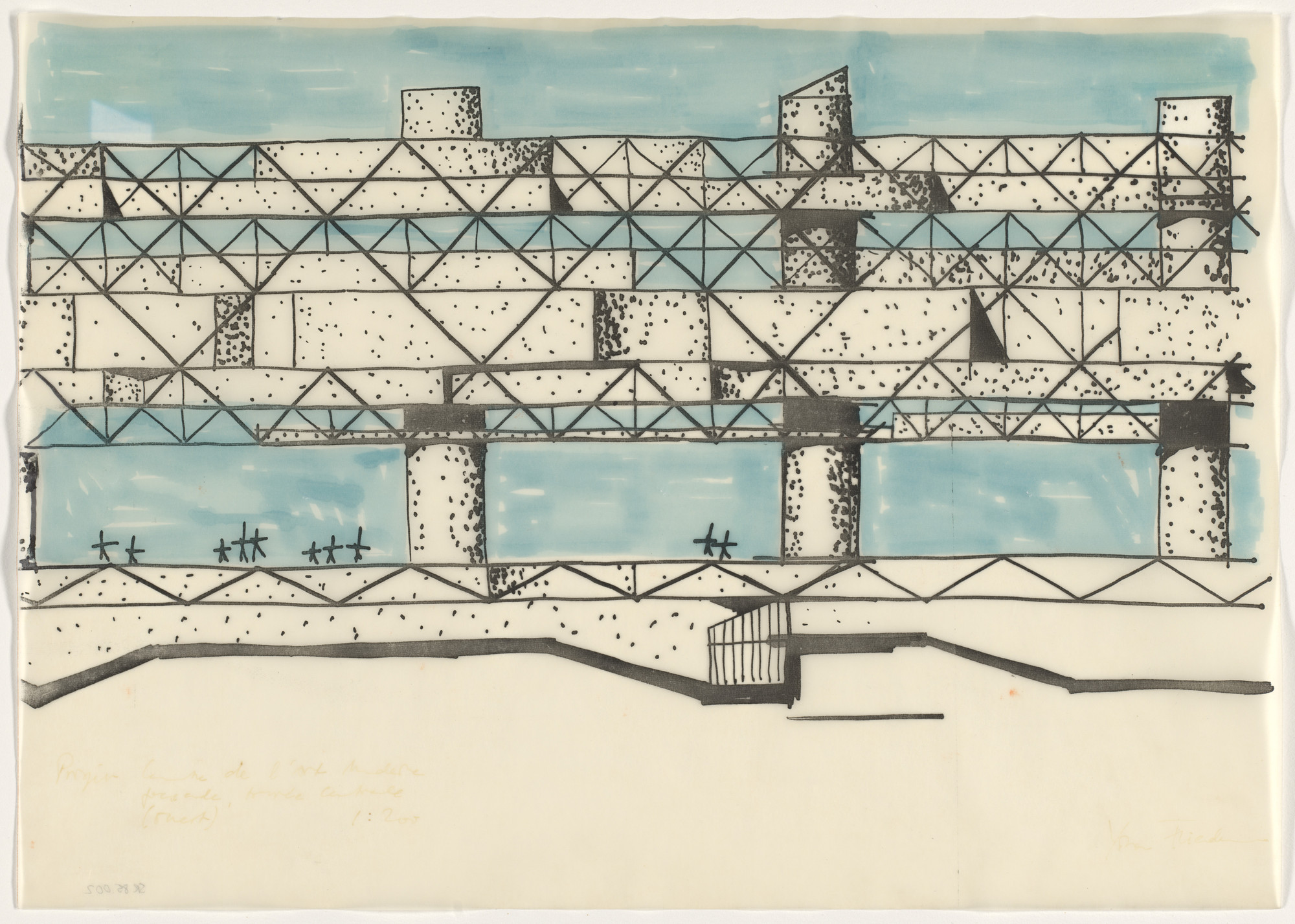

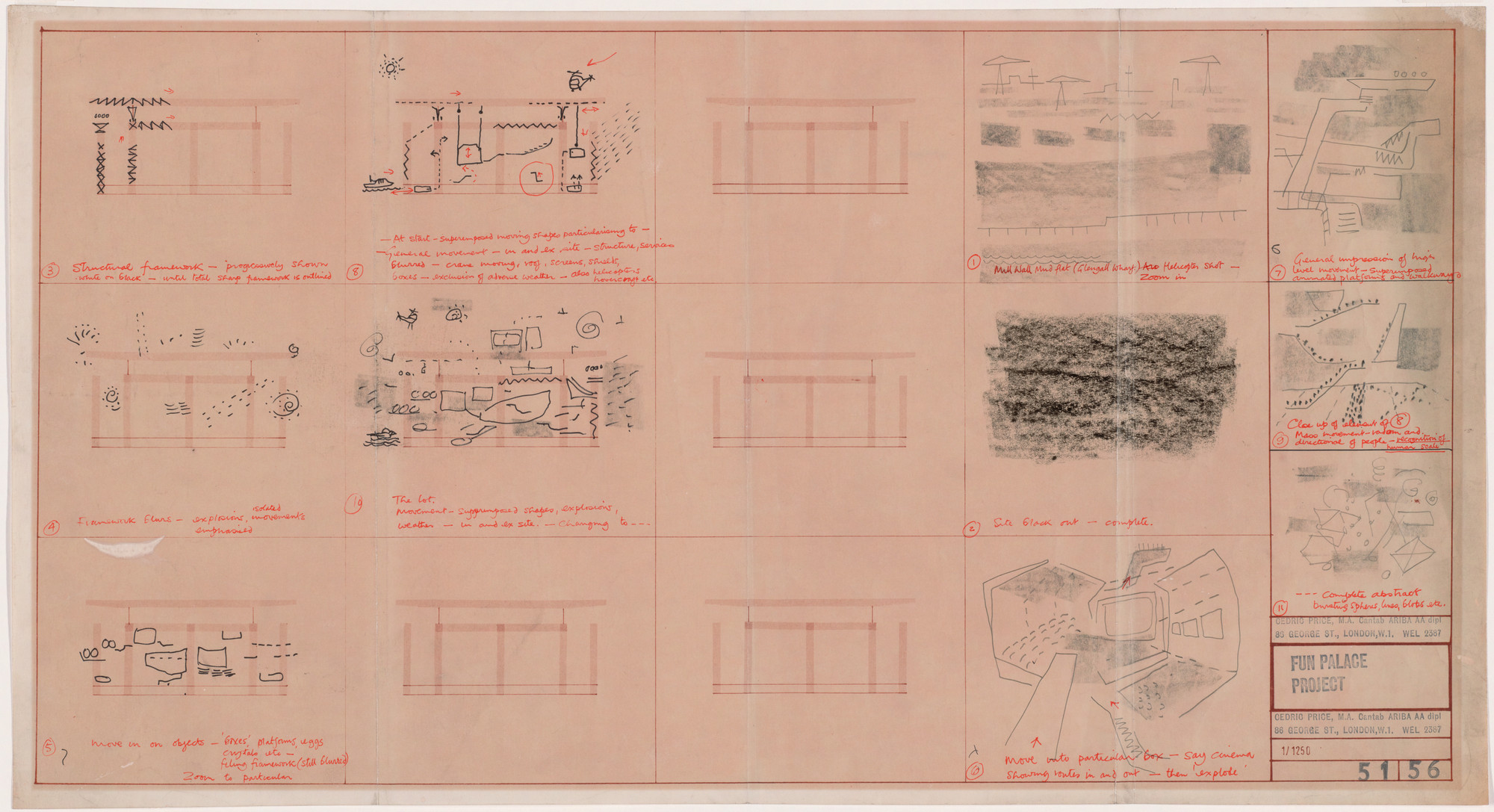

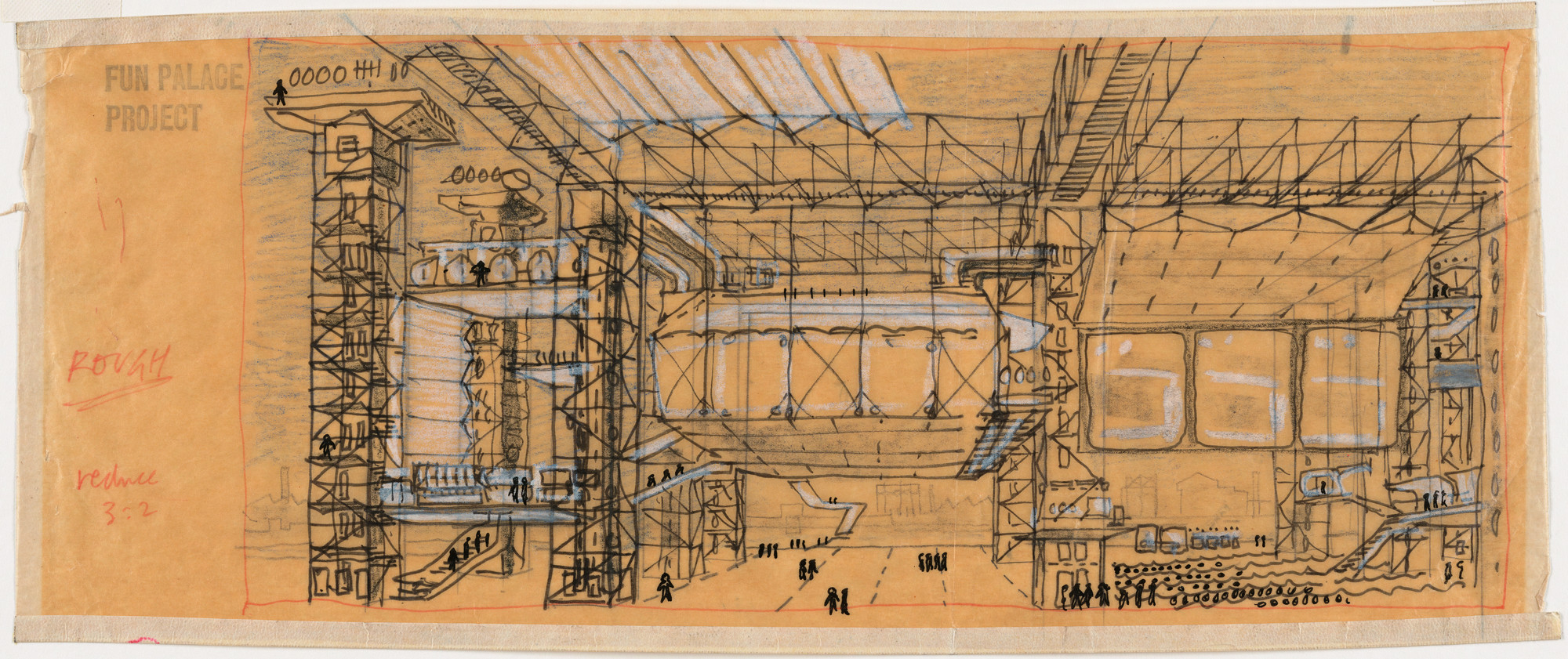

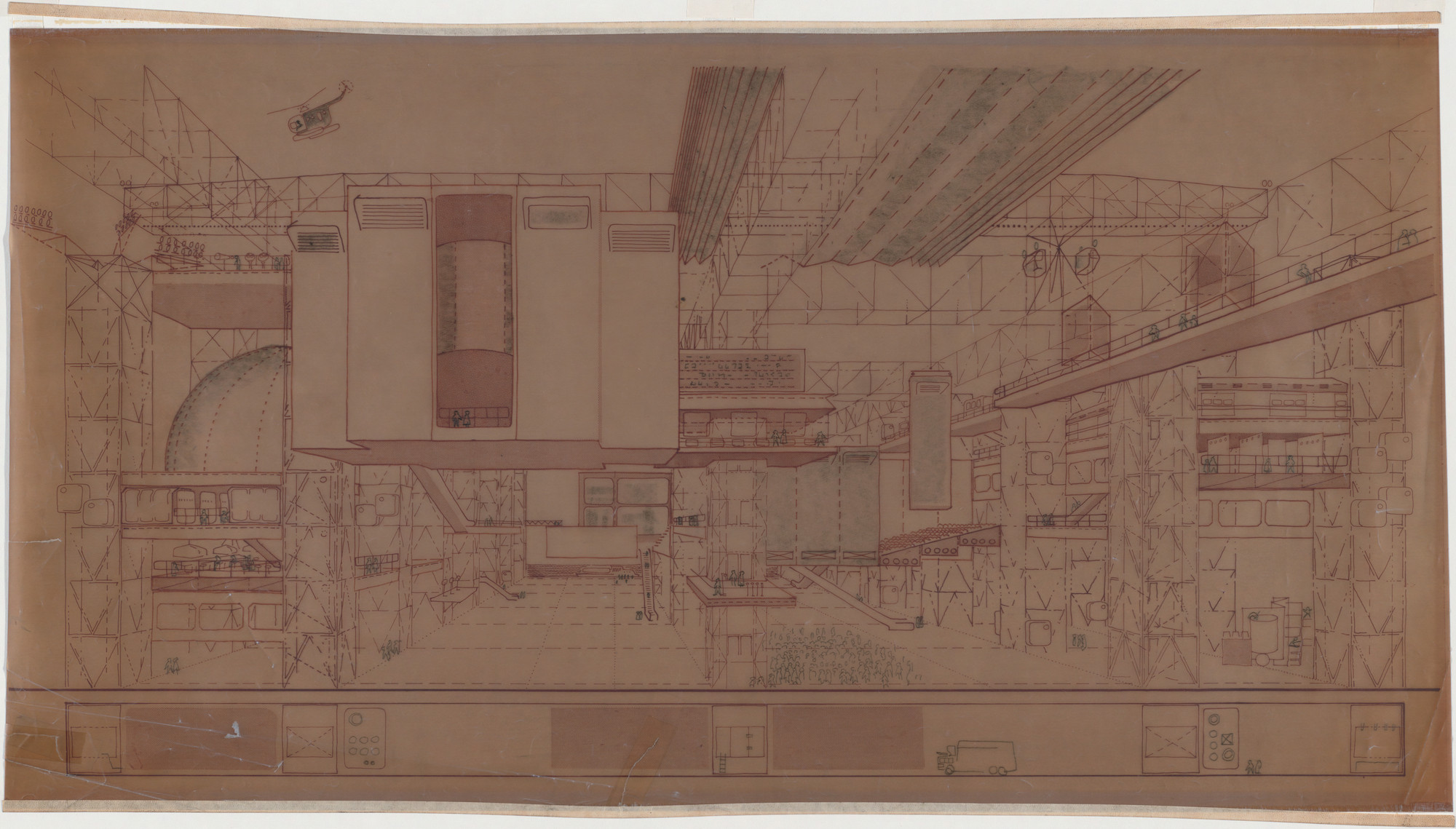

CEDRIC PRICEBritish, born 1934

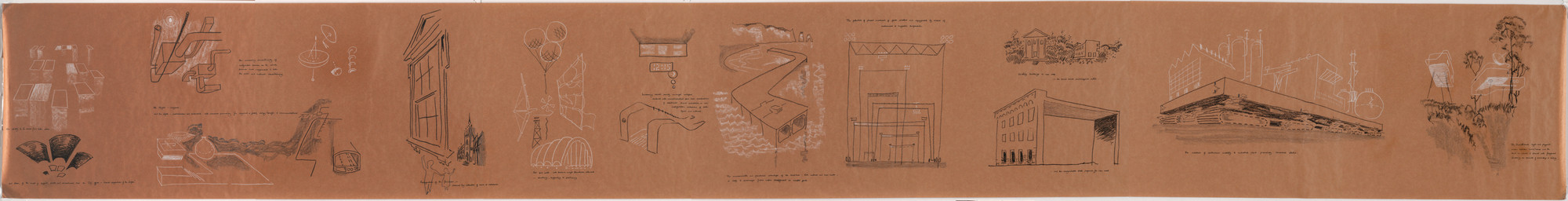

Cedric Price. Fun Palace for Joan Littlewood Project, Stratford East, London, England (Storyboard for film and sketches). 1959–1961. Felt-tipped pen, graphite, crayon, and ink stamps on diazotype. 15 × 27½" (38.1 × 69.9 cm)

Fun Palace for Joan Littlewood was conceived for the East End of London as a "laboratory of fun" and "a university of the streets." Although it was never realized, unlike other visionary projects of the 1960s it was fully intended to be built. Designed as a flexible framework into which programmable spaces can be plugged, the structure has as its ultimate goal the possibility of change at the behest of its users. Price belonged to a generation of British architects and educators who used architecture both to address the future and as the ultimate social art. Price's personal vision of the city was inventive and playful and expressed his sense of architecture’s moral obligations toward its users. Price was fascinated by new technology and believed that it should both serve the public and further human freedom. He was determined that his work would not impose physical or psychological constraints upon its occupants nor reduce them to a standard form—unlike typical modern architecture.

Cedric Price. Fun Palace for Joan Littlewood Project, Stratford East, London, England (Perspective). 1959–1961. Ink, crayon, and graphite on gelatin silver print, with self-adhesive paper dot. 13½ × 26½" (34.3 × 67.3 cm)

Cedric Price. Fun Palace for Joan Littlewood Project, Stratford East, London, England (Perspective). 1959–1961. Felt-tipped pen, ink, graphite, crayon and ink stamp on tracing paper with tape. 6½ × 15⅞" (16.5 × 40.3 cm)

Cedric Price. Fun Palace for Joan Littlewood Project, Stratford East, London, England (Perspective). 1959–1961. Graphite on diazotype. 17½ × 33" (44.5 × 83.8 cm)

Cedric Price. Fun Palace for Joan Littlewood Project, Stratford East,

London, England (Aerial perspective from cockpit). 1959–1961. Cut-and-pasted painted paper on gelatin silver print with white ink. 8¾ × 10½" (22.2 × 26.7 cm)

ARATA ISOZAKIJapanese, born 1931

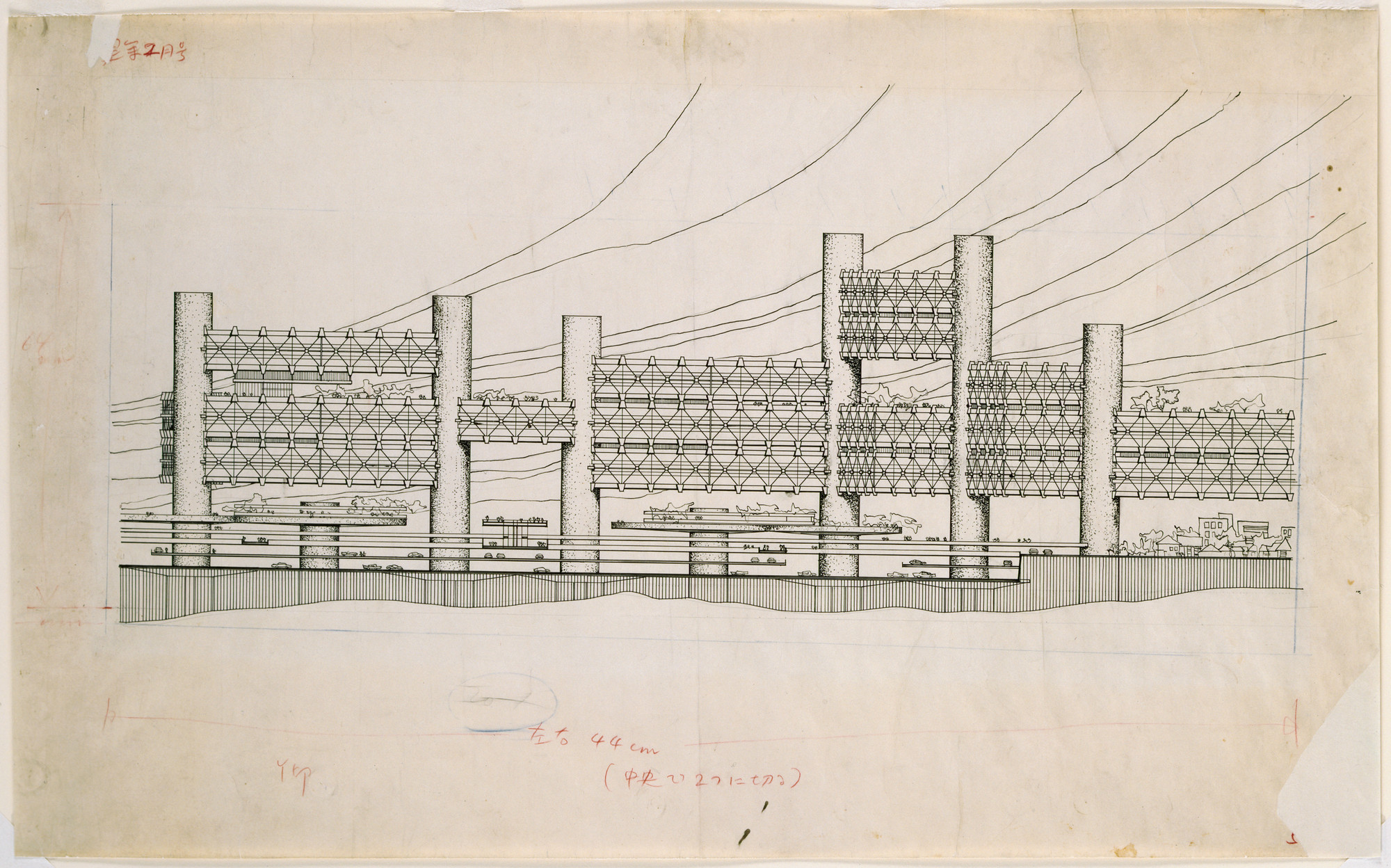

In Arata Isozaki's unrealized design for the Joint Core System spatial construction, massive pylons support elevated transportation, housing, and office systems as well as parks and walkways, suspended above the existing city. This scheme was undertaken at a time when Kenzo Tange and a group of five young architects working in his office, known as the Metabolists, were creating radical solutions for restructuring Tokyo's rapid and uncontrolled postwar growth. As a member of Tange's office, Isozaki was inspired by Tange's proposal for a multilevel urban construction above the city. But, unlike Tange's plan, in which a square support system limits expansion to four directions, Isozaki's round columns permit growth in any direction.

Arata Isozaki. Joint Core System, project, Shinjuku, Tokyo, Japan (Elevation). 1960. Ink and color pencil on paper. 20⅞ × 33¾" (53 × 85.7 cm)

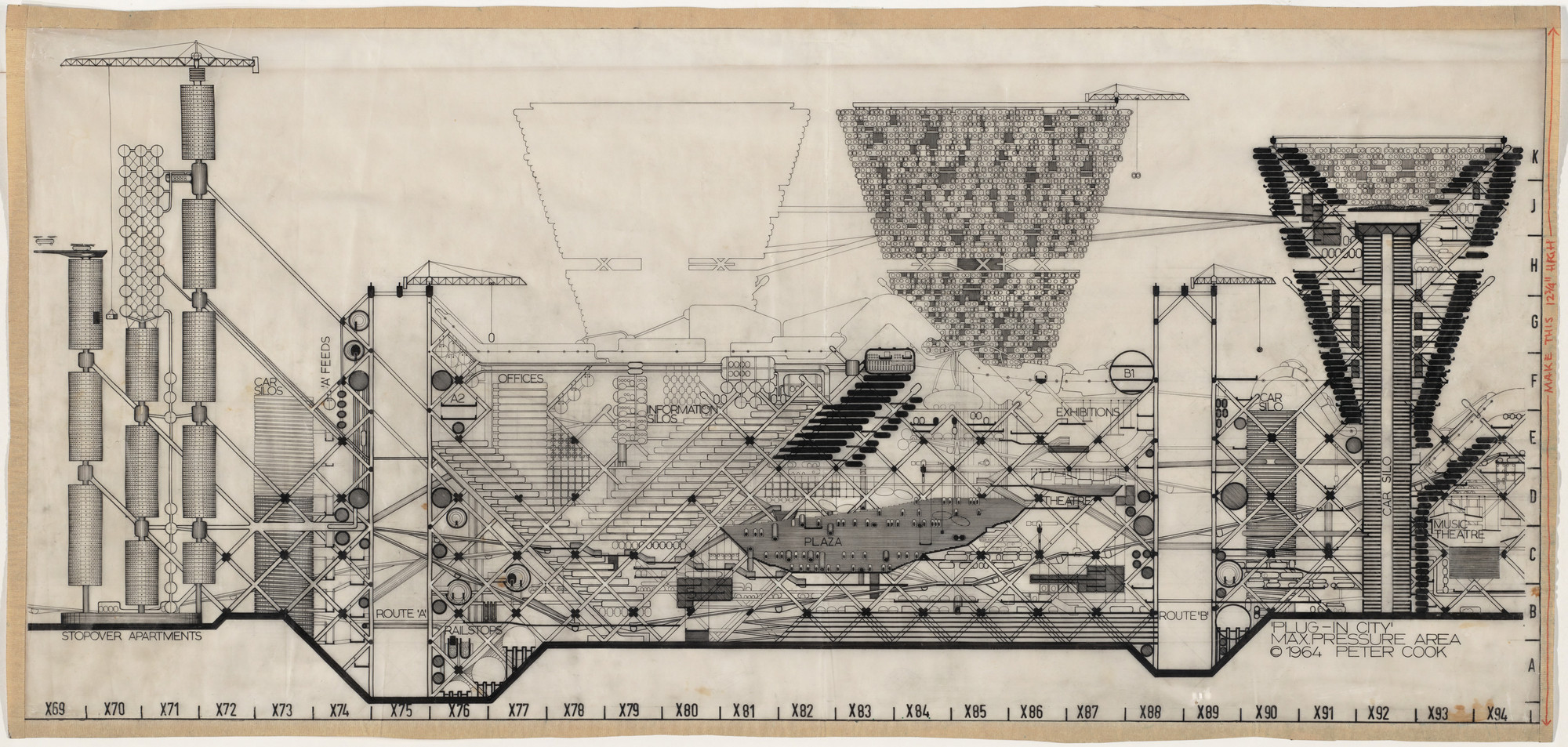

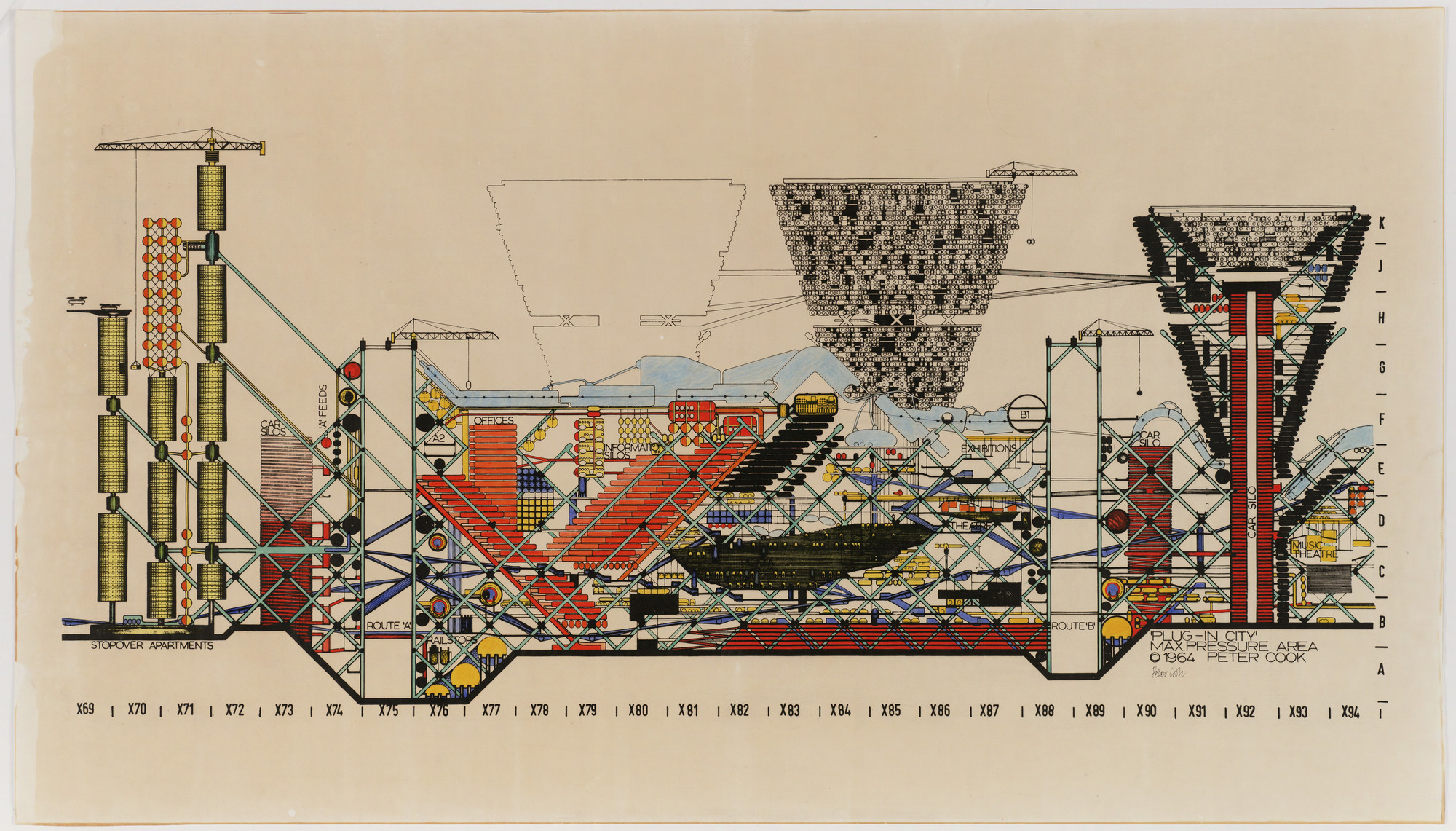

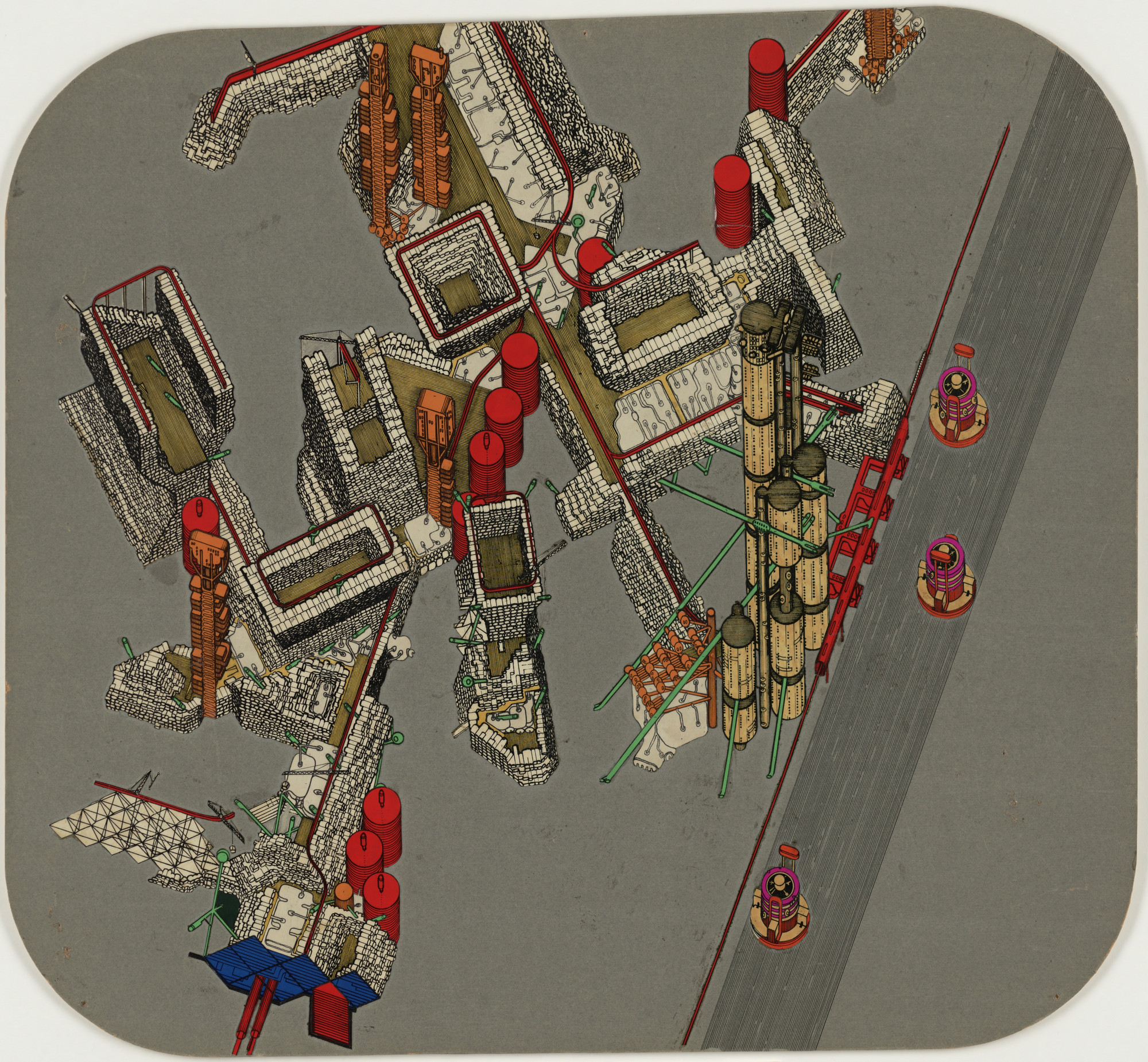

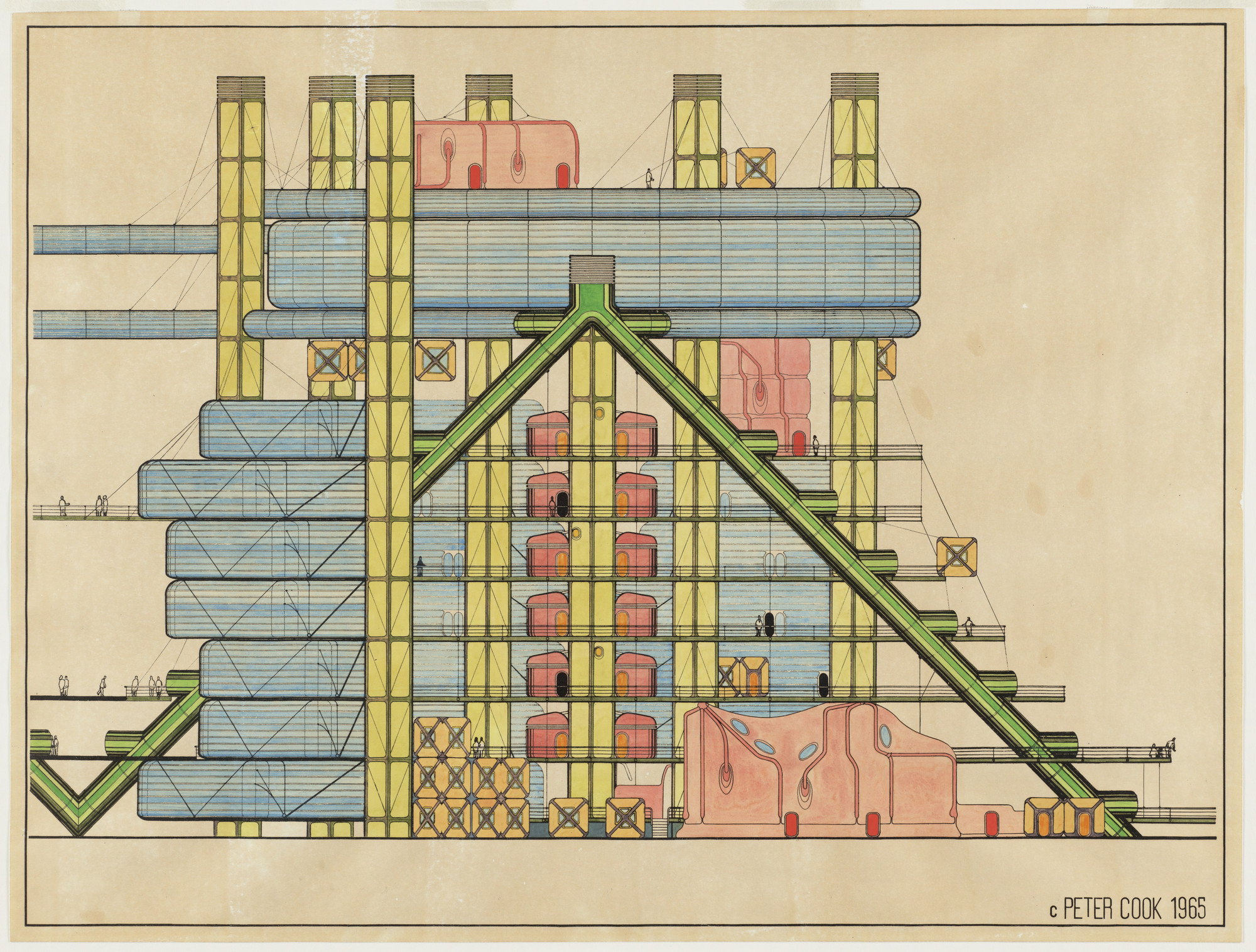

PETER COOK (Archigram)British, born 1936

Peter Cook, a founding member of Archigram, was instrumental in fostering the British counterculture in the 1960s. He promoted the view that the preceding modernist period's functionalist architecture was worn out. His proposed remedy, the Plug-in City, was a visionary urban megastructure incorporating residences, access routes, and essential services for its inhabitants. Intended to accommodate and encourage changes necessitated by obsolescence, on an as-needed basis, the building nodes (houses, offices, supermarkets, universities), each with a different lifespan, would plug into a main "craneway", itself designed to last only forty years. The overall flexible and impermanent form would thus reflect the needs and collective will of the inhabitants.

Peter Cook. Plug-in City: Maximum Pressure Area, project (Section). 1964. Ink and graphite on tracing paper with masking tape. 21¾ × 45⅝" (55.2 × 115.9 cm)

Peter Cook. Plug-in City: Maximum Pressure Area, project (Section). 1964. Ink and gouache on photomechanical print. 32⅞ × 57 11/16" (83.5 × 146.5 cm)

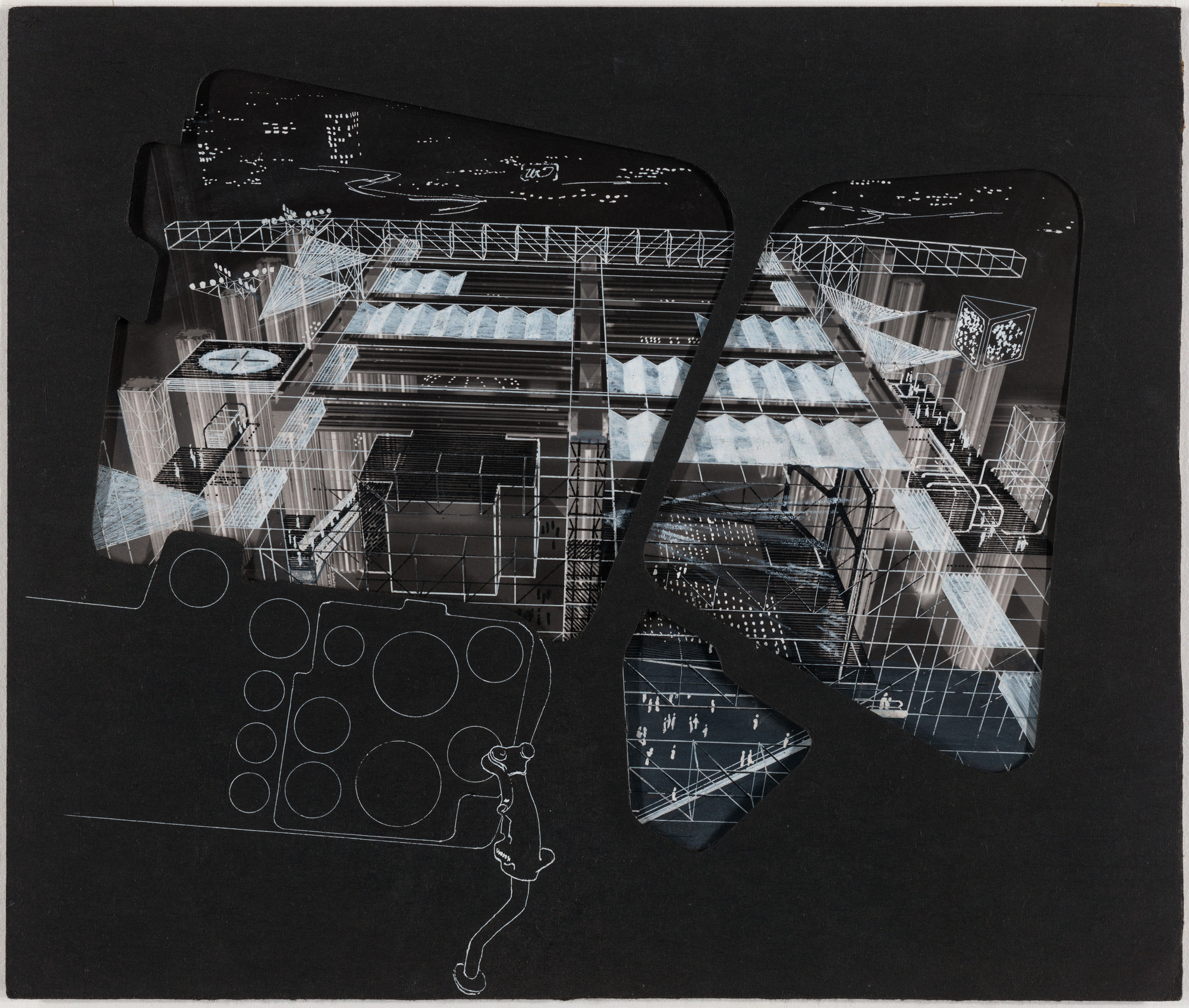

Peter Cook. Plug-In City, project (Axonometric). 1964. Cut-and-pasted printed papers with graphite and clear and colored self-adhesive polymer sheets on gray paper-covered board with ink. 27⅜ × 29⅞" (69.5 × 75.9 cm)

Peter Cook. Plug-in University Node, project (Elevation). 1965. Watercolor on photolithograph. 26⅛ × 34½" (66.4 × 87.6 cm)

RON HERRON (Archigram)British, 1930–1994

Ron Herron, a founding member of Archigram, the influential British group known for its admixture of science-fiction and pop culture, created his Walking City out of an indefinite number of giant roaming pods containing different urban and residential areas. The pods could be connected by retractable corridors and, together, form a conglomerate metropolis. This literally mobile and indeterminate architecture was not so much a serious proposition for a structure as a commentary on the way in which change dominates every aspect of the modern city.

Ron Herron. Cities: Moving, Master Vehicle-Habitation Project, Aerial Perspective. 1964. Ink and graphite on tracing paper. 21¾ × 32¾" (55.2 × 83.2 cm)

Ron Herron. Walking City on the Ocean, project (Exterior perspective). 1966. Cut-and-pasted printed and photographic papers and graphite covered with polymer sheet. 11½ × 17" (29.2 × 43.2 cm)

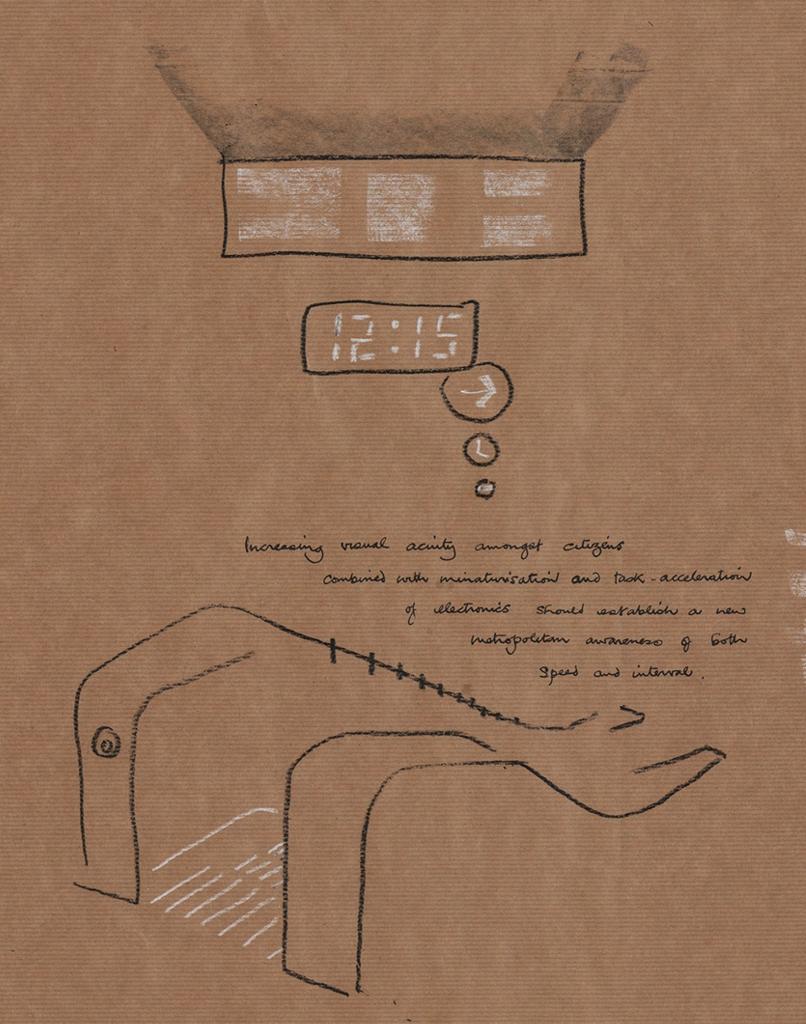

CEDRIC PRICEBritish, born 1334

Cedric Price came on to the British architectural scene in the late 1950s, a time in which housing complexes, schools, industrial parks and new towns were springing up all over Britain. There was an overriding belief in a socially responsibly architecture and general feeling of optimism about the future and architecture's capacity to improve the environment. Price, however, was determined that his work would not impose physical or psychological constraints upon its occupants nor reduce them to standards, as did modernist architecture. Through the pairing of humor and playfulness with complete conviction, Price's projects all attest to his belief in an architecture that provides inhabitants as well as viewers individual freedoms. Technology, based on the paradigm of a flexible network rather than a static structure, played an essential role in Price's work.

Cedric Price. City of the Future Project (Perspectives). c. 1965. Crayon, ink, and graphite on paper. 36 × 15' 9¾" (91.4 × 482 cm)

Cedric Price. City of the Future Project (Perspectives). Detail

Cedric Price. City of the Future Project (Perspectives). Detail

Cedric Price. City of the Future Project (Perspectives). Detail

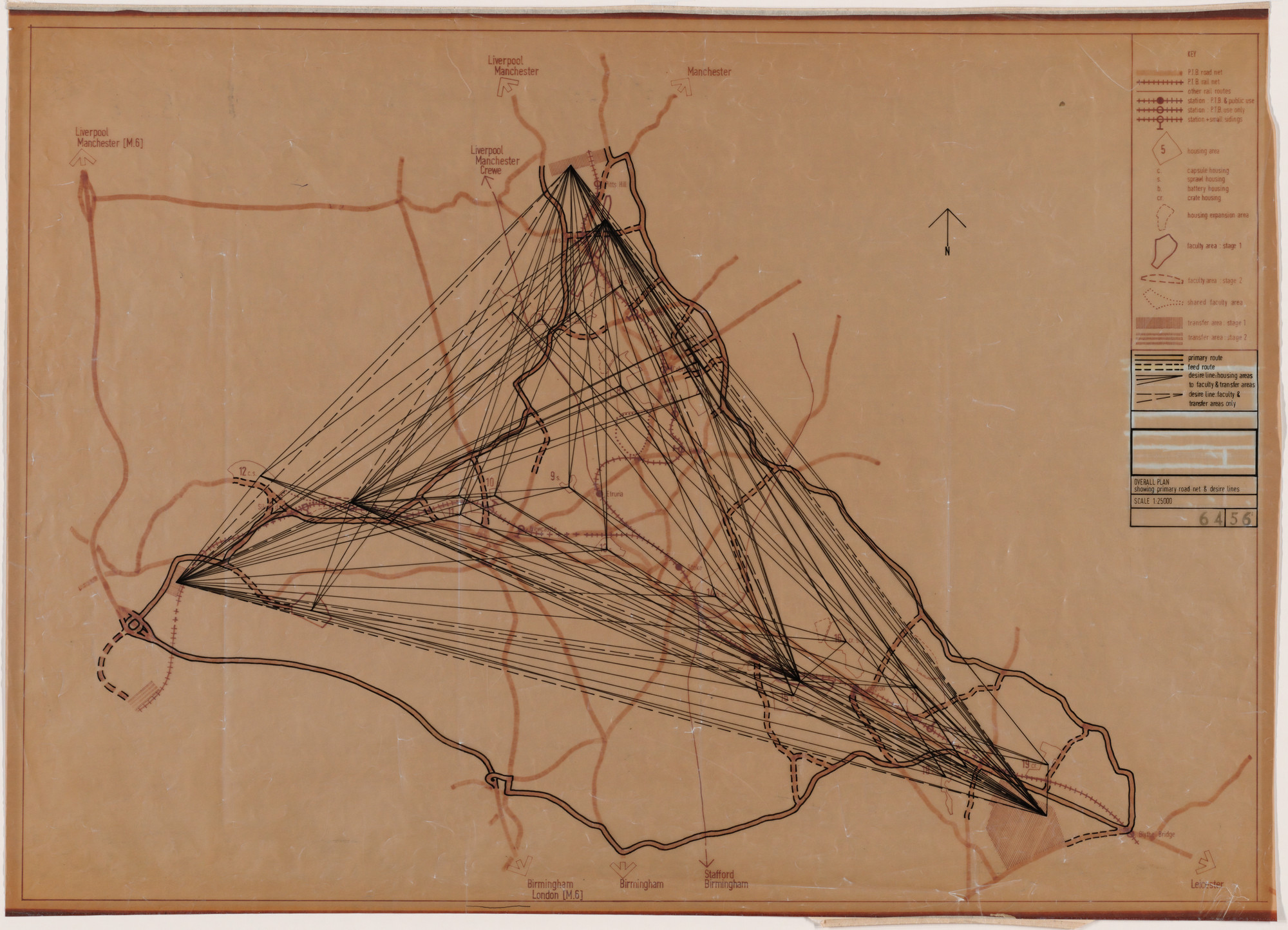

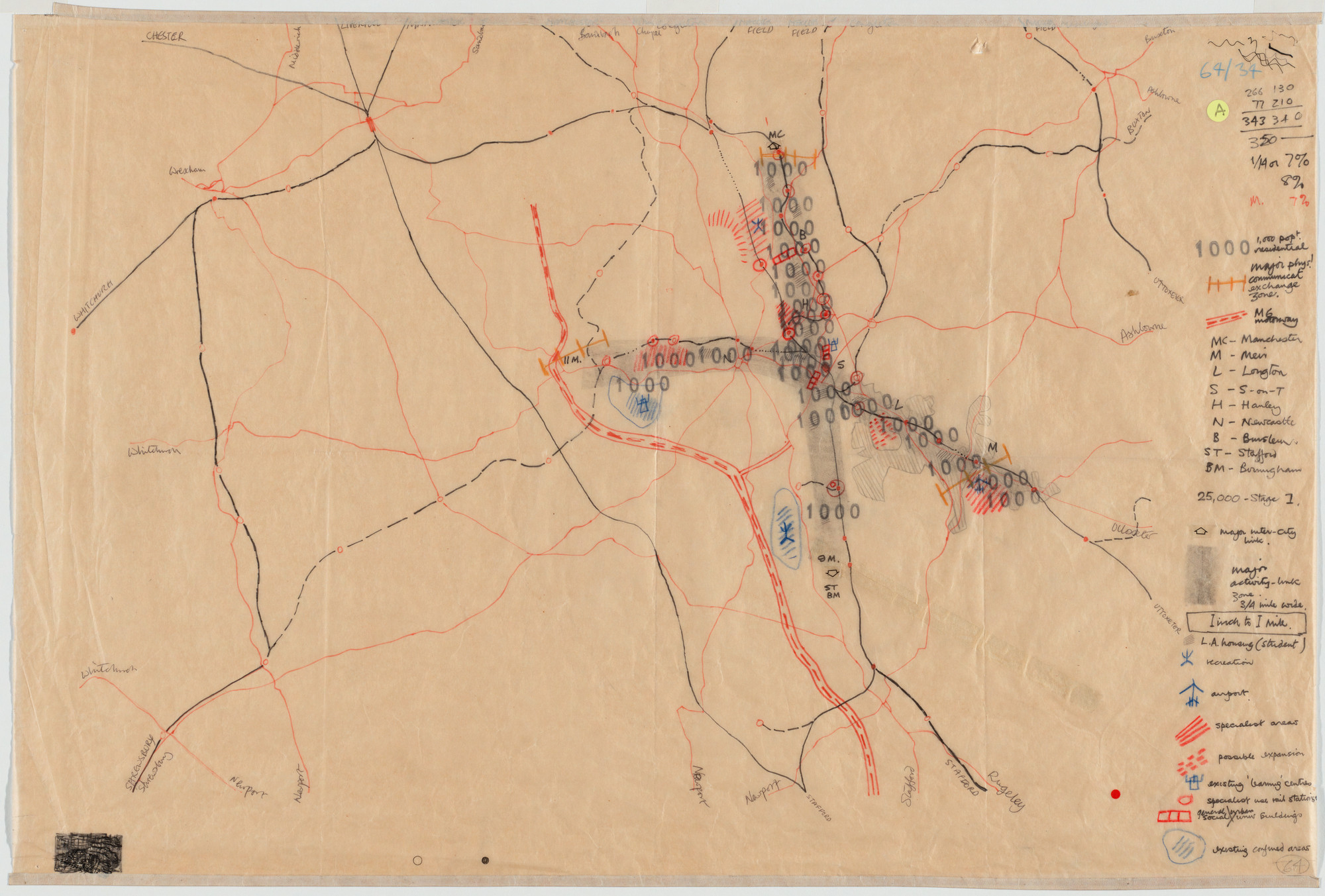

Cedric Price. Potteries Thinkbelt Project, Staffordshire, England (Plan of Desire Lines-Physical and Mental Exchange). 1964–1966. Ink and ink stamp on diazotype. 23¾ × 33⅛" (60.3 × 84.1 cm)

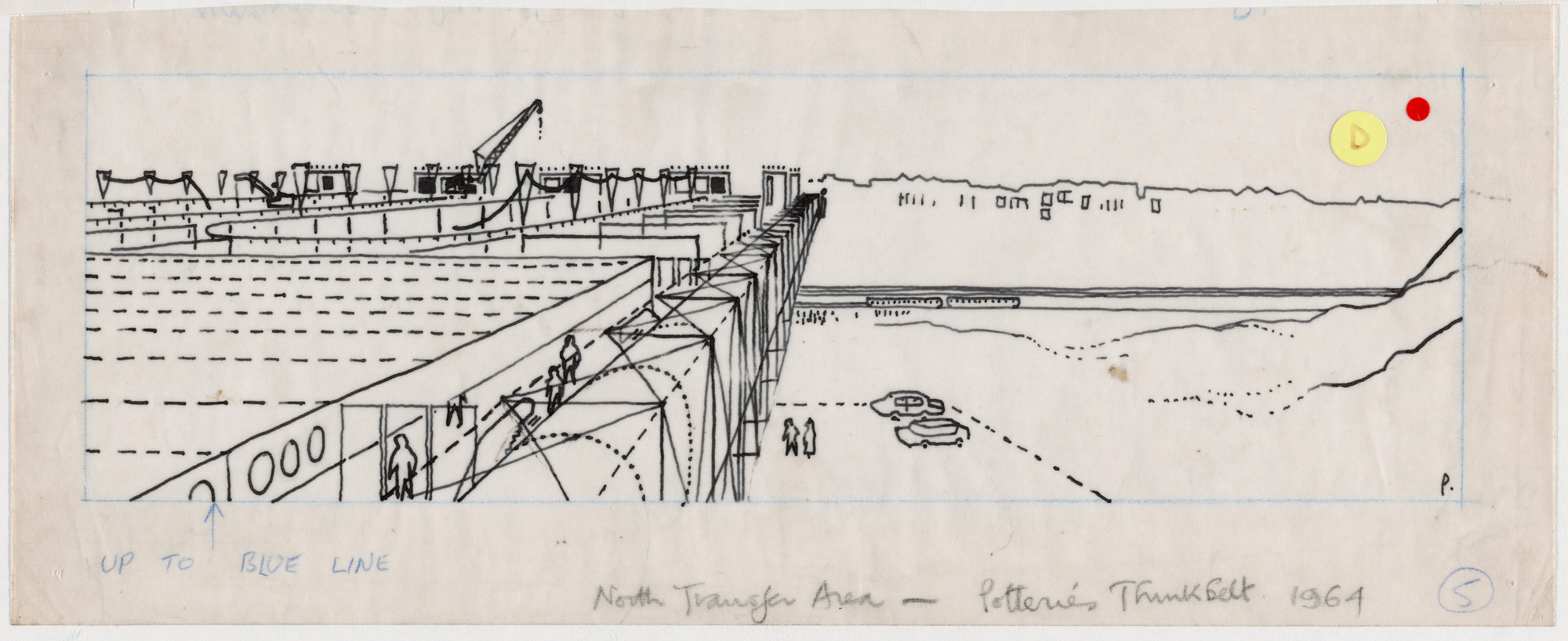

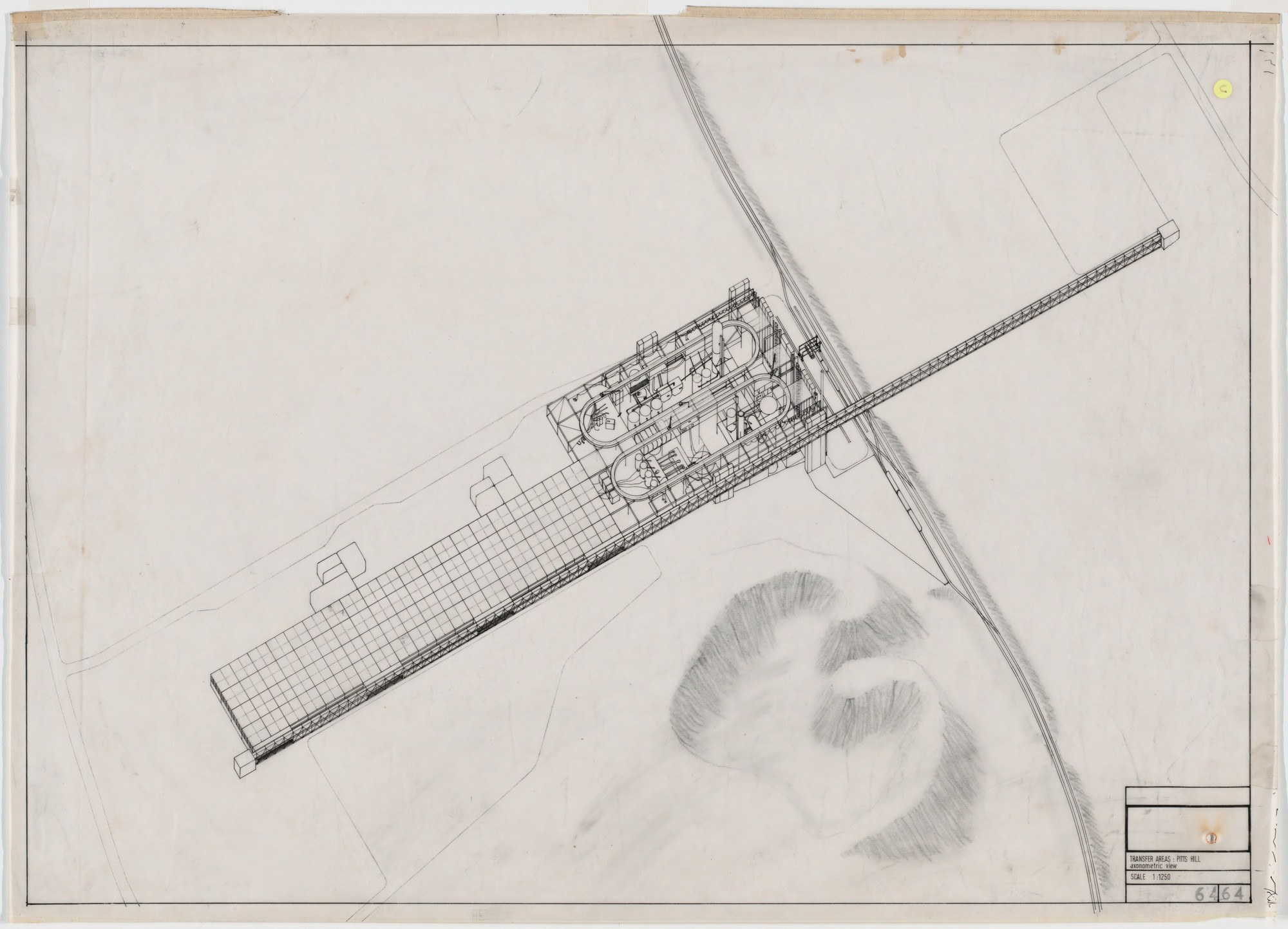

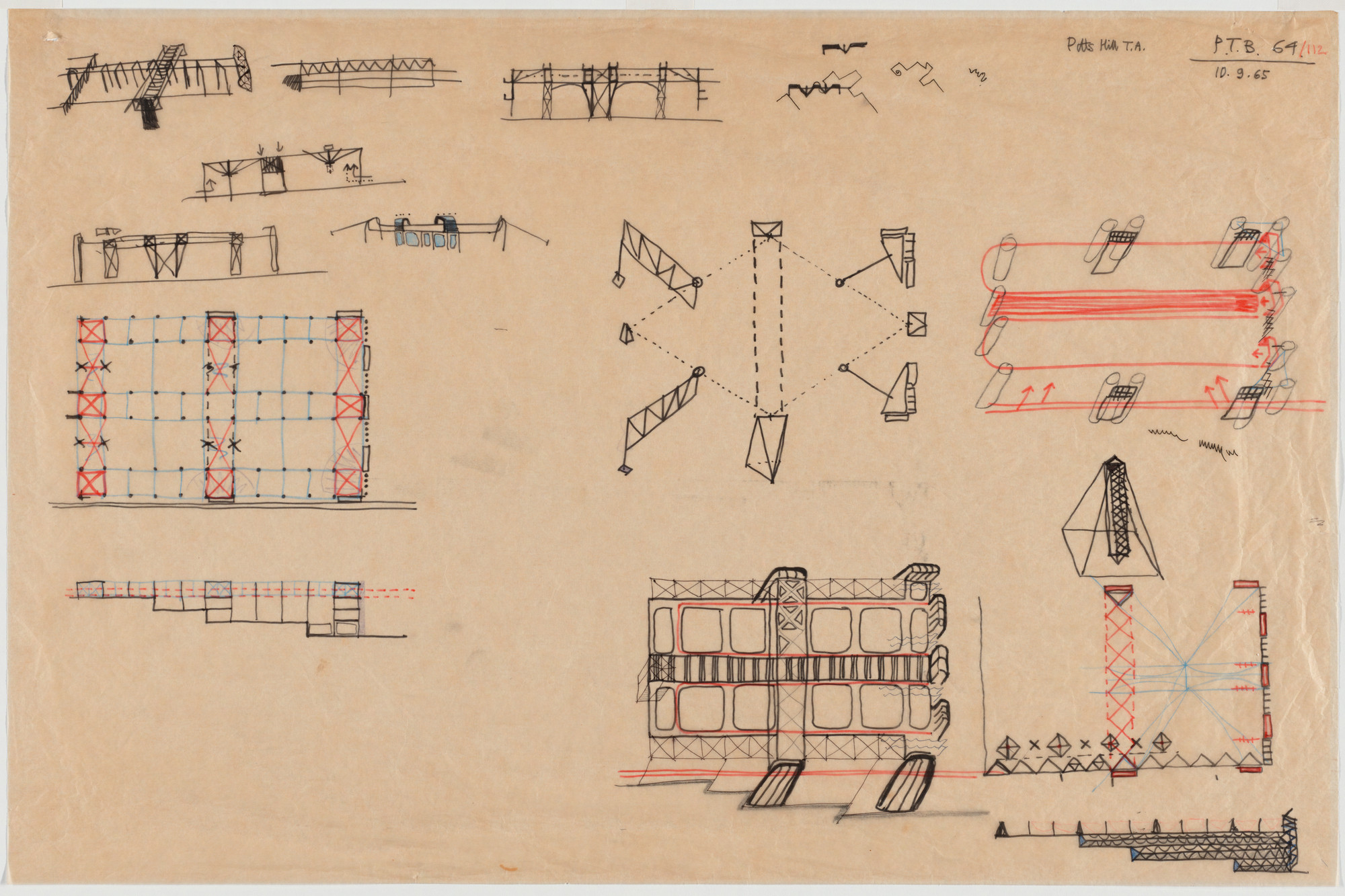

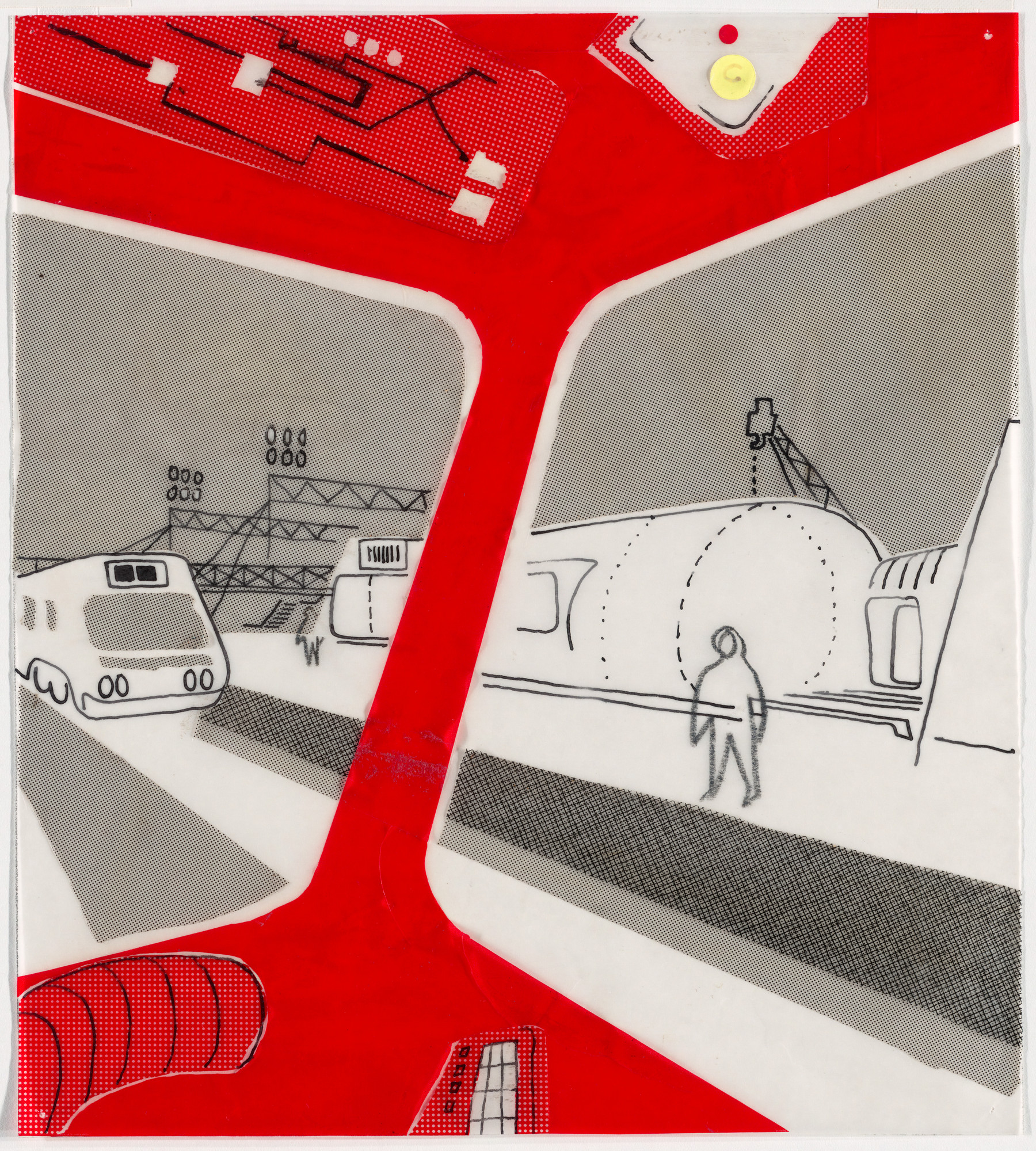

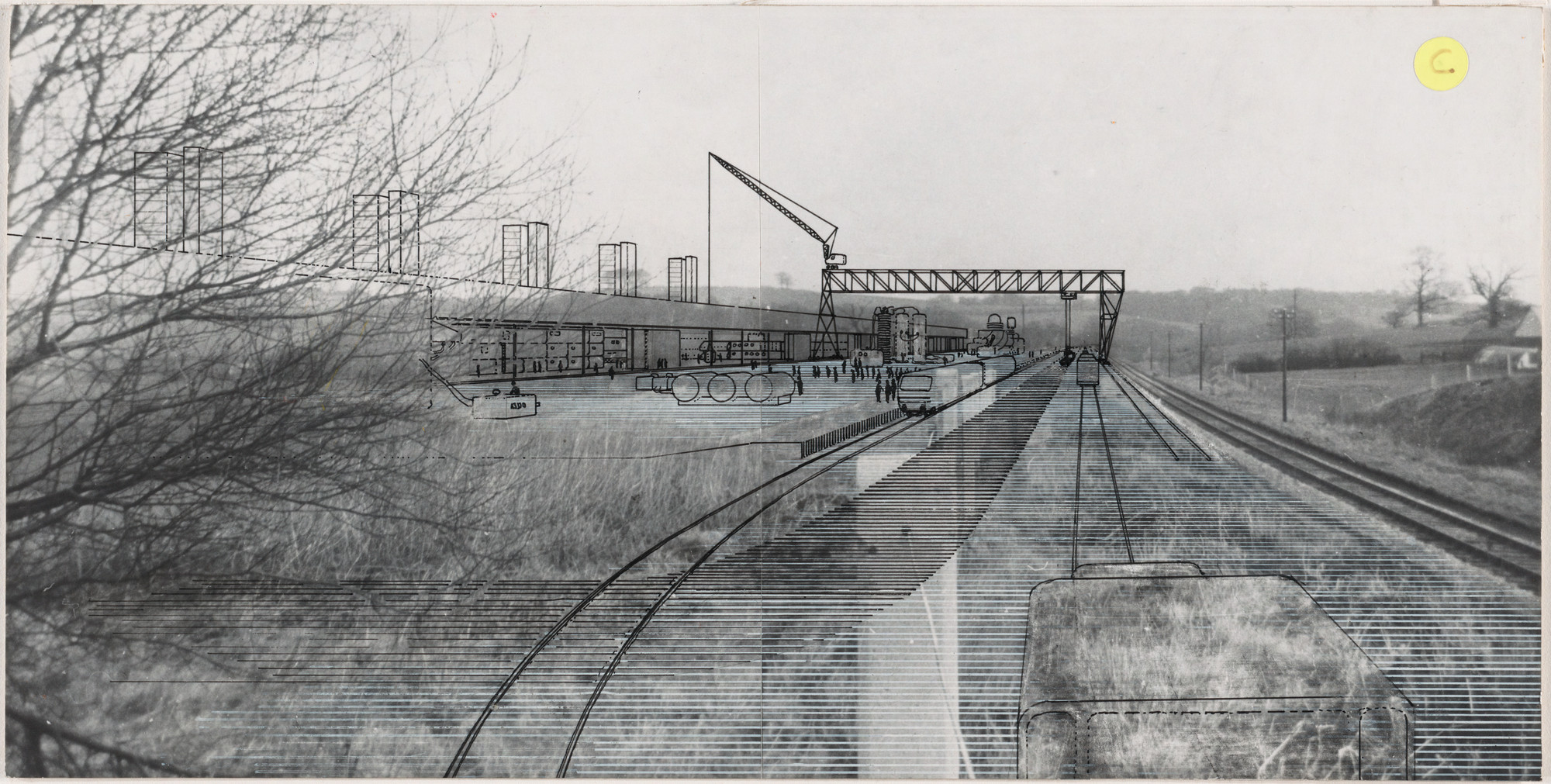

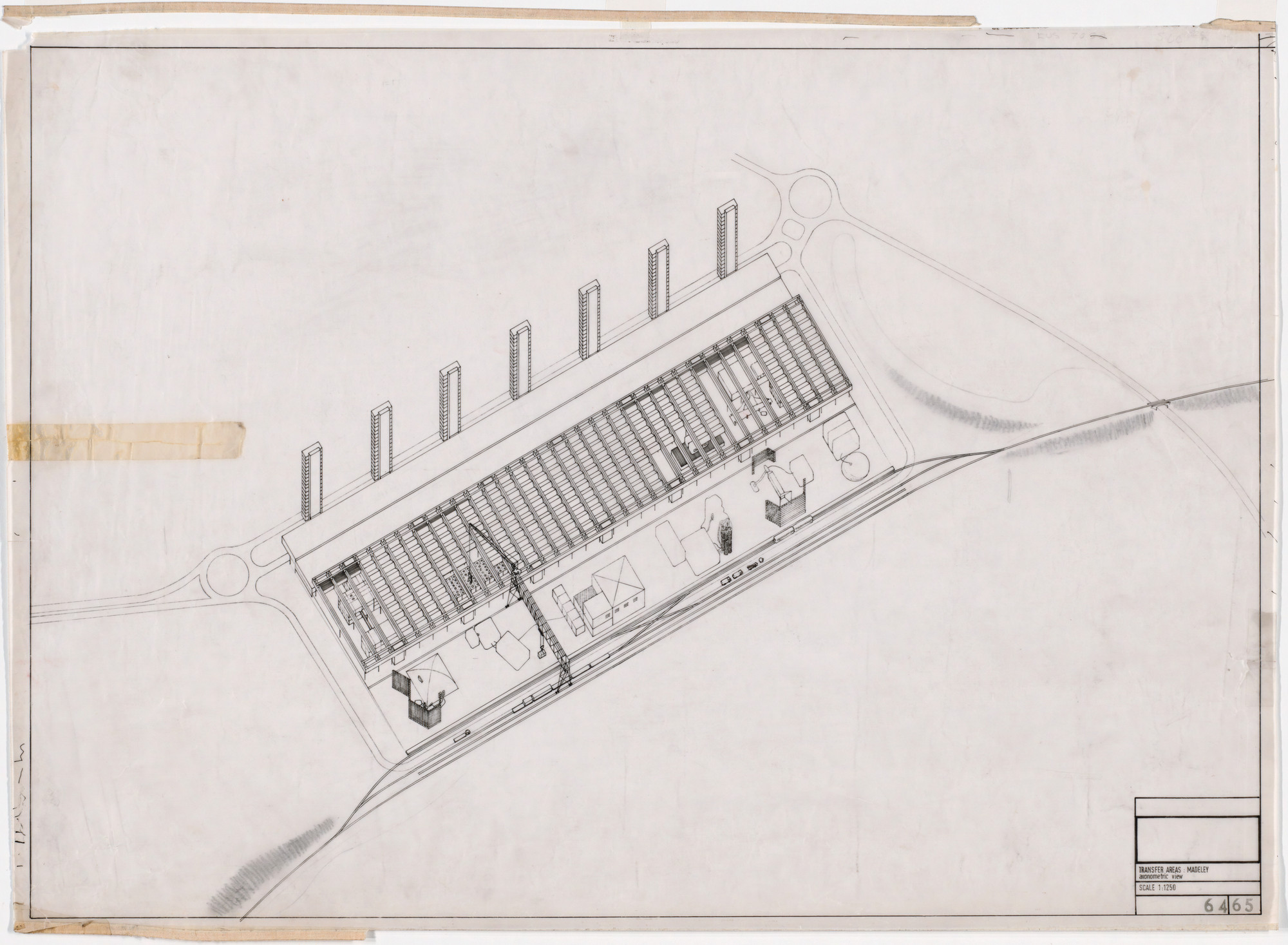

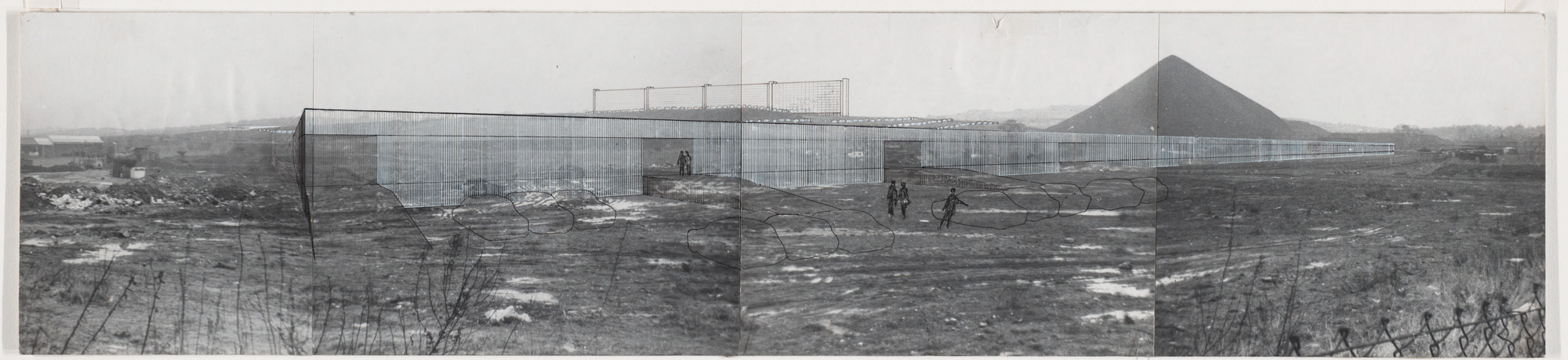

Potteries Thinkbelt was Cedric Price's critique of the traditional university system. Situated in a decaying industrial landscape, rather than in the usual urban or rural site, the Thinkbelt occupied one hundred square meters of the once-vital Staffordshire Potteries. It was designed to be an infinitely extendable network, as opposed to a centralized campus, and to create a widespread community of learning while also promoting economic growth. The framework for the network was a hundred-year-old railway system no longer in use. Not only would it transport people between housing and learning areas, but the cars themselves would become mobile teaching units. Complete with inflatable lecture theaters, foldout desks, and information carrels, the units could be combined and transferred to various sites as needed.

Cedric Price. Potteries Thinkbelt Project, Staffordshire, England (Plan). 1964–1966. Ink, white ink, color pencil, ink stamp, self-adhesive polymer sheet, and self-adhesive paper dot on tracing paper. 20 × 29¾" (50.8 × 75.6 cm)

Cedric Price. Potteries Thinkbelt Project, Staffordshire, England (Perspective of Pitts Hill, North Transfer Area). 1964–1966. Ink, color pencil, and graphite on tracing paper, with self-adhesive paper dot. 8¾ × 17½" (22.2 × 44.5 cm)

Cedric Price. Potteries Thinkbelt Project, Staffordshire, England (Axonometric of Pitts Hill, Transfer Area). 1964–1966. Ink and graphite with ink stamp and self-adhesive paper dot. 24⅝ × 34¼" (62.5 × 87 cm)

Cedric Price. Potteries Thinkbelt Project, Staffordshire, England (Sketches of Pitts Hill, Early Transfer Area). 1964–1966. Ink, color ink, and color pencil on tracing paper. 19⅝ × 29⅞" (49.8 × 75.9 cm)

Cedric Price. Potteries Thinkbelt Project, Staffordshire, England (Perspective of Mobile Teaching Machines [cover design for the October, 1966 issue of the journal Architectural Design]). 1964–1966. Self-adhesive printed polymer sheets with ink and graphite on tracing paper, with self-adhesive paper dots. 12¼ × 11" (31.1 × 27.9 cm)

Cedric Price. Potteries Thinkbelt Project, Staffordshire, England (Perspective of Madeley Transfer Area). 1964–1966. Ink and white ink on selectively abraded gelatin silver print, mounted on board with self-adhesive paper dot. 7¼ × 14⅜" (18.4 × 36.5 cm)

Cedric Price. Potteries Thinkbelt Project, Staffordshire, England (Axonometric of Madeley Transfer Area). 1964–1966. Ink and ink stamp on tracing paper. 24 × 34" (61 × 86.4 cm)

Cedric Price. Perspective of Battery, Crate, and Capsule Housing, Longton Site. 1964–1966. Ink and graphite on gelatin silver print. 6⅝ × 29⅝" (16.8 × 75.2 cm)

Cedric Price. Potteries Thinkbelt Project, Staffordshire, England (Perspective of Battery, Sprawl, and Capsule Housing, Hanley Site). 1964–1966. Ink and crayon on selectively abraded gelatin silver prints, mounted on board. 6⅜ × 16⅞" (16.2 × 42.9 cm)

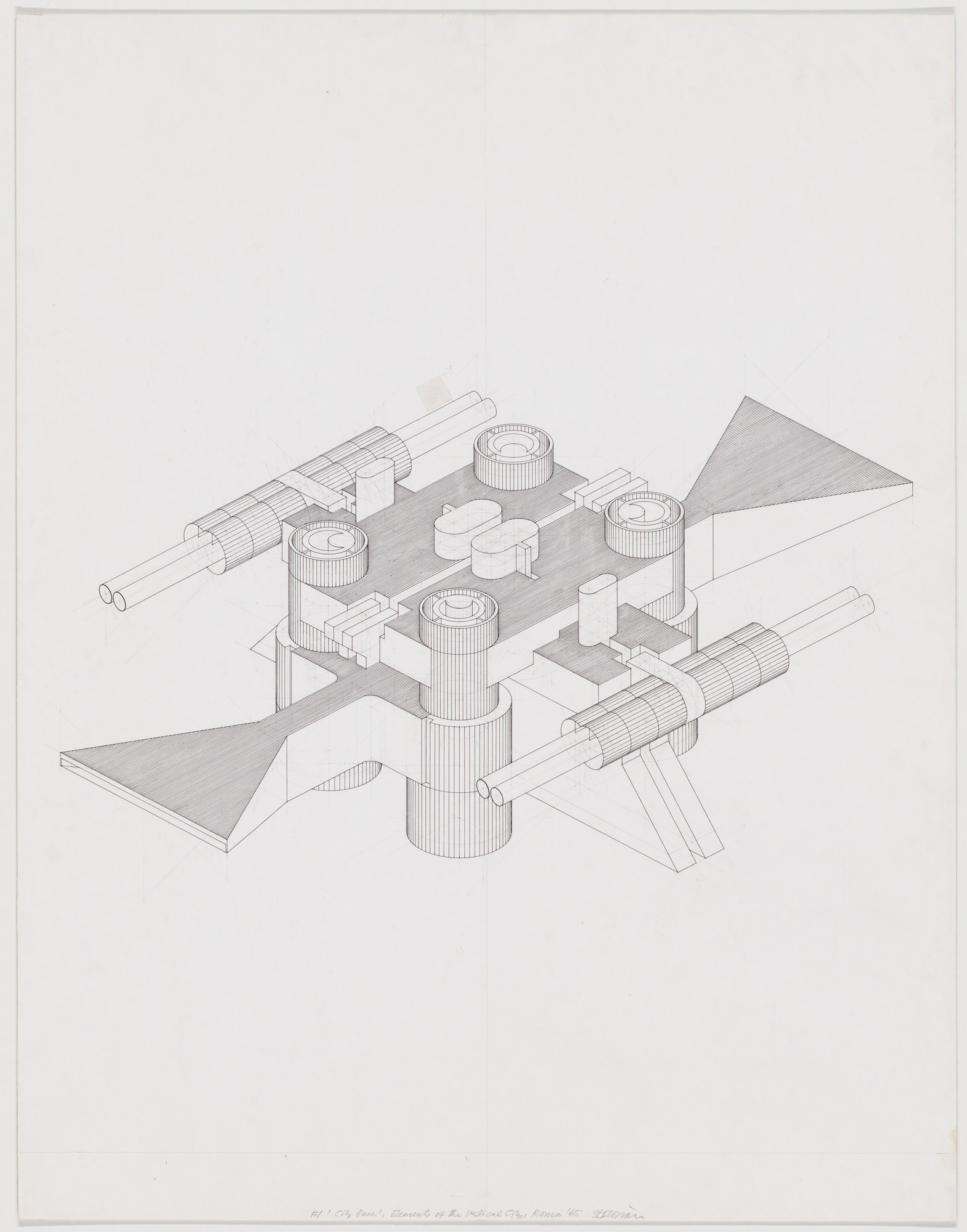

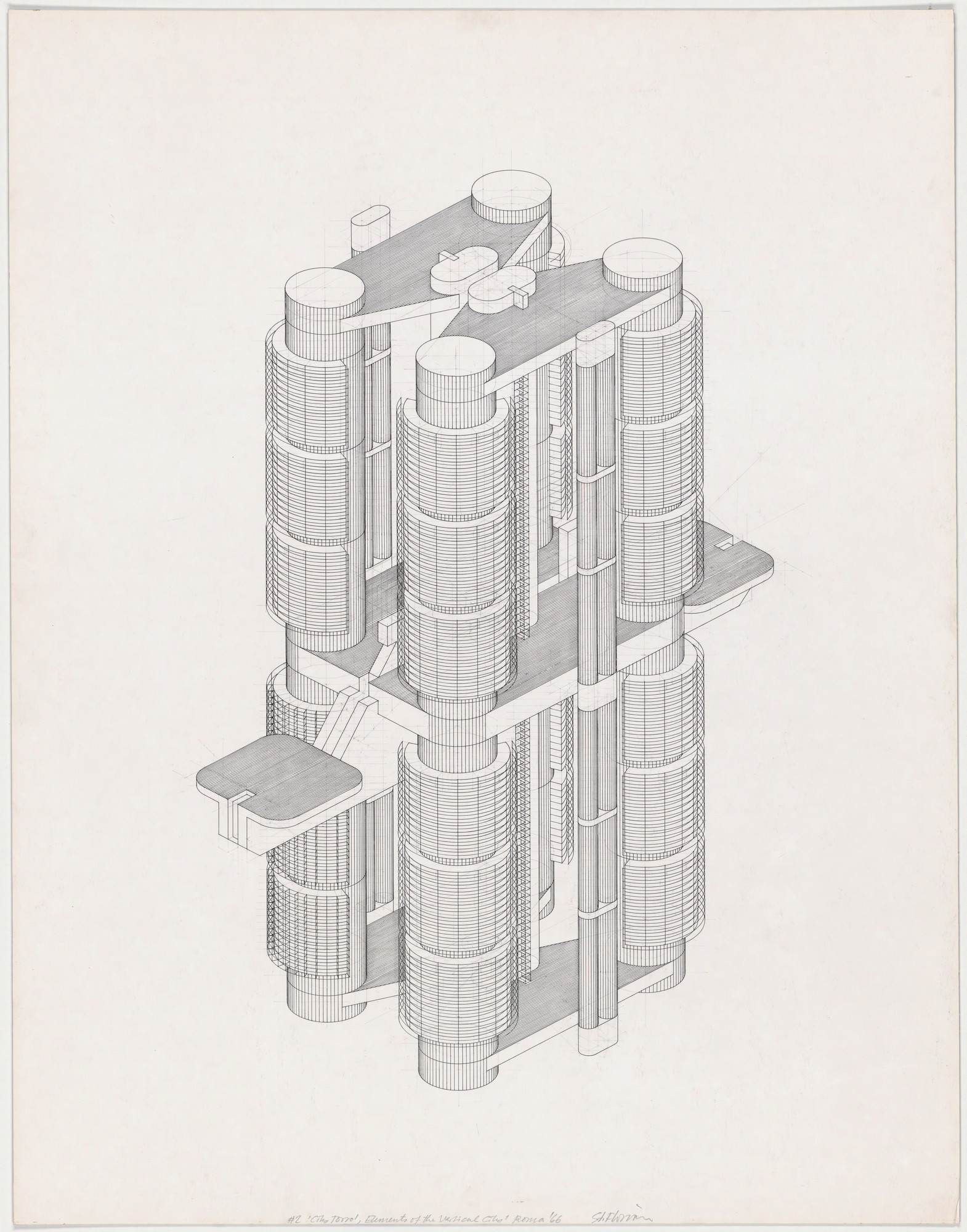

FRIEDRICH ST. FLORIANAmerican, born Austria, 1932

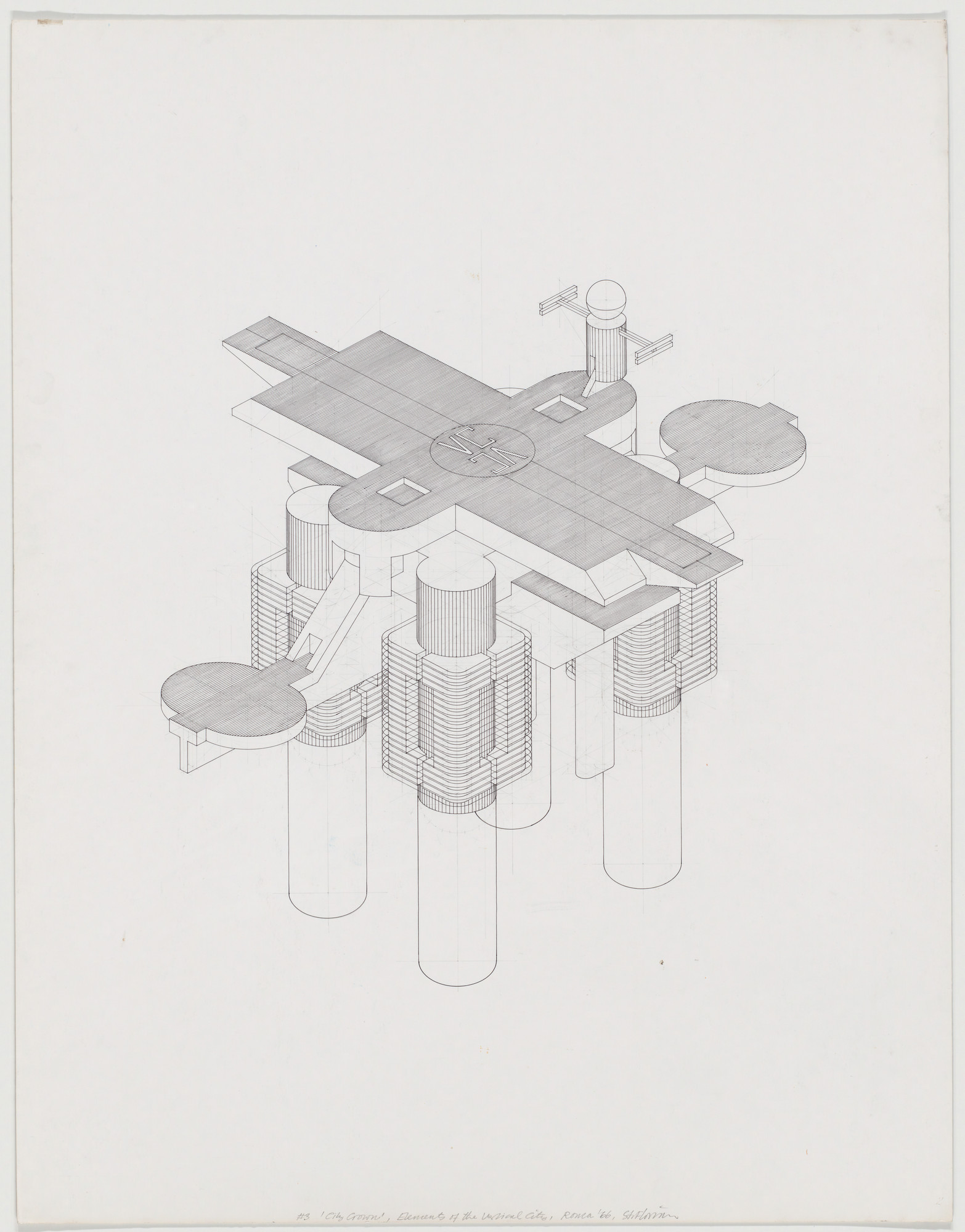

Friedrich St. Florian's Vertical City, a tower of three hundred stories, was a visionary urban proposal that he believed could actually be built. The cylindrical form of the structural components was intended to allow the city to soar above the clouds, thus granting at least a hundred additional days of sunlight to those at the top. The regions beyond the clouds were designated for those most in need of light—hospitals, schools, and the elderly—which could be continually provided by solar technology. Like the modern linear city, the vertical version had centralized stations for transportation, communication, and energy.

Friedrich St. Florian. Elements of the Vertical City, project, Rome, Italy, Axonometric of base. 1966. Ink, graphite, and gouache on board. 36 × 28" (91.4 × 71.1 cm)

Friedrich St. Florian. Elements of the Vertical City, project, Rome, Italy, Axonometric of torso. 1966. Ink, graphite, and gouache on board. 36 × 28" (91.4 × 71.1 cm)

Friedrich St. Florian. Elements of the Vertical City, project, Rome, Italy, Axonometric of crown. 1966. Ink, graphite, and gouache on board. 36 × 28" (91.4 × 71.1 cm)

PAUL RUDOLPHAmerican, 1918–1997

In the late 1960s, an expressway running across lower Manhattan, linking New Jersey to Brooklyn, Queens, and Long Island via the Holland Tunnel and the Manhattan and Williamsburg bridges, was under discussion. Paul Rudolph's proposed Y-shaped corridor was designed to leave the city's infrastructure intact, and suggested a new approach to city building, which claimed that transportation networks could bind rather than divide communities. At key points in the 'transportation corridor' (central hub, bridge or tunnel entries) there were multilevel, stacking pedestrian plazas, people movers, and parking—all above and below existing bridge and rail systems. Tall, stepped-back residential buildings would provide light, air, and views. Flanking the corridor at the gateways, and in conjunction with new building types, they would generate urban space.

Paul Rudolph. Lower Manhattan Expressway Project, New York, New York (Perspective to the East). 1972. Ink and graphite on paper. 40 × 33½" (101.6 × 85.1 cm)

SUPERSTUDIOItalian group, 1966–86Cristiano Toraldo di Francia, born 1941Gian Piero Frassinelli, born 1939Alessandro Magris, born 1941Roberto Magris, bom 1935Adolfo Natalini, born 1941

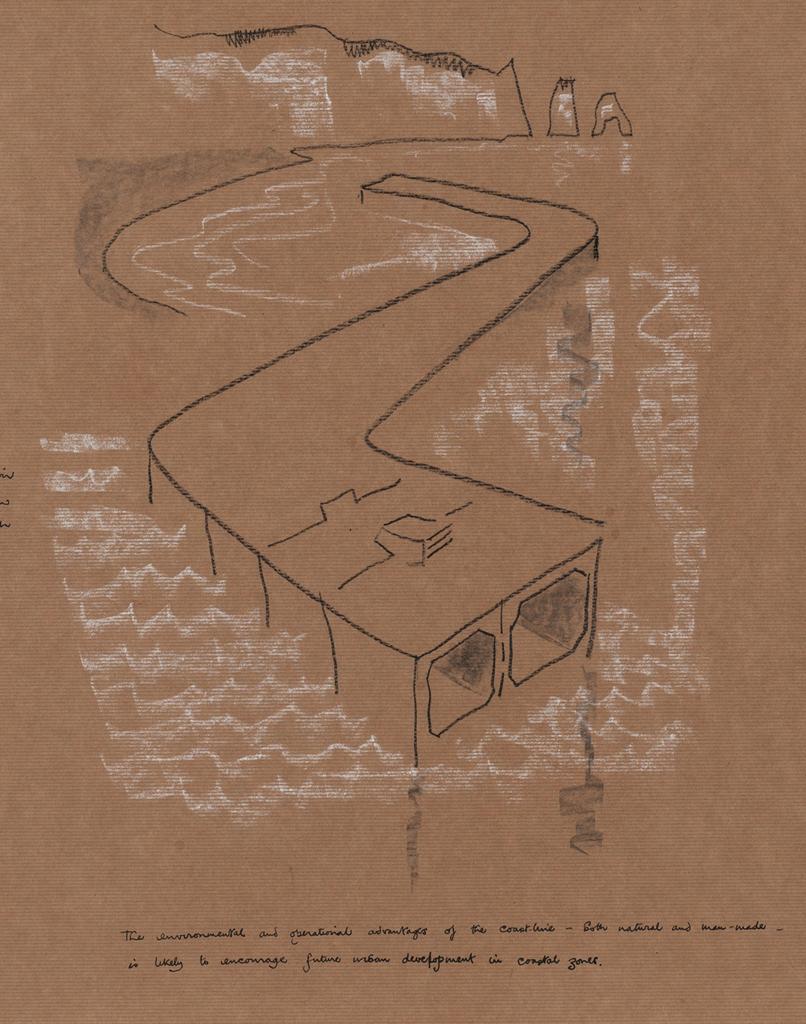

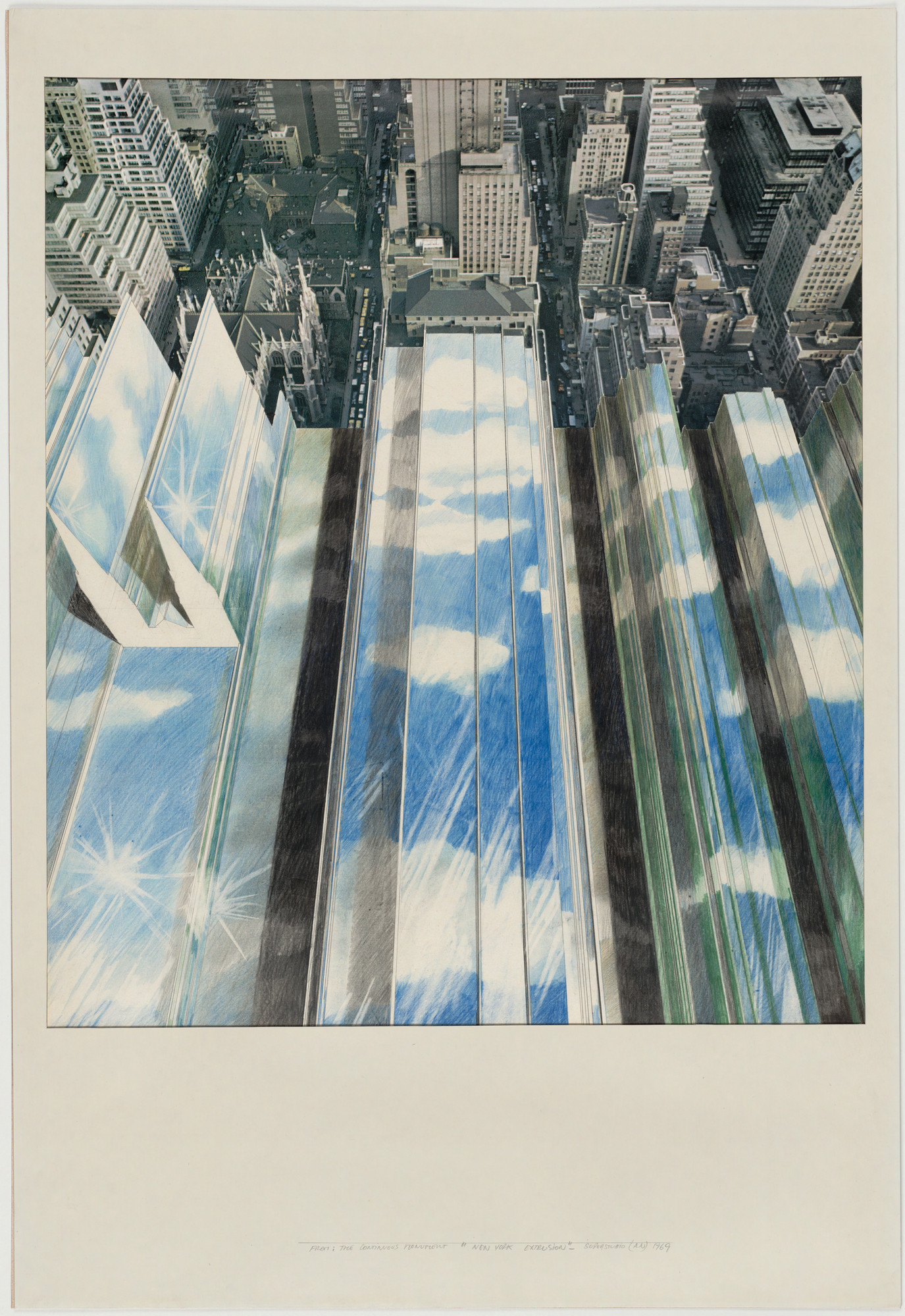

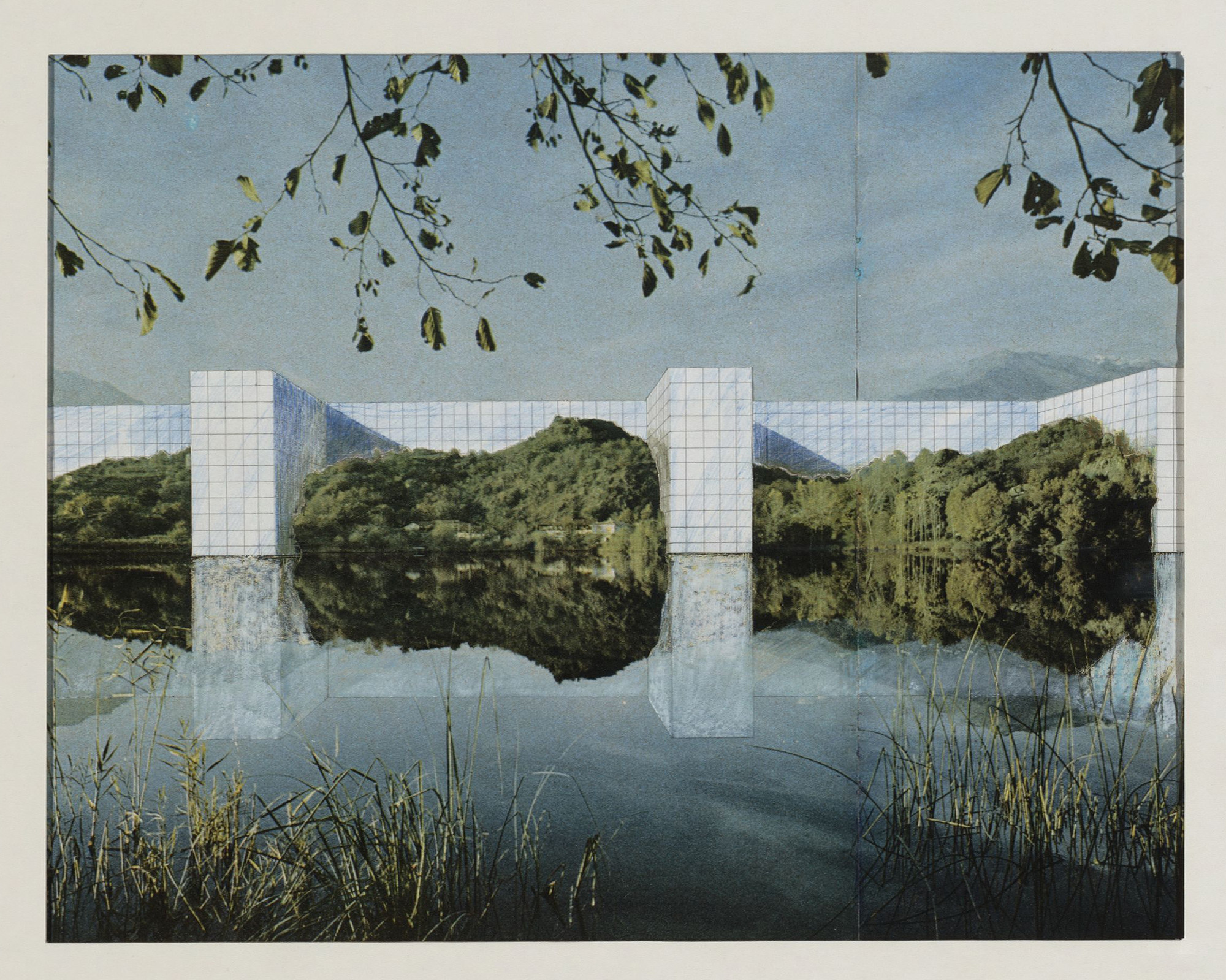

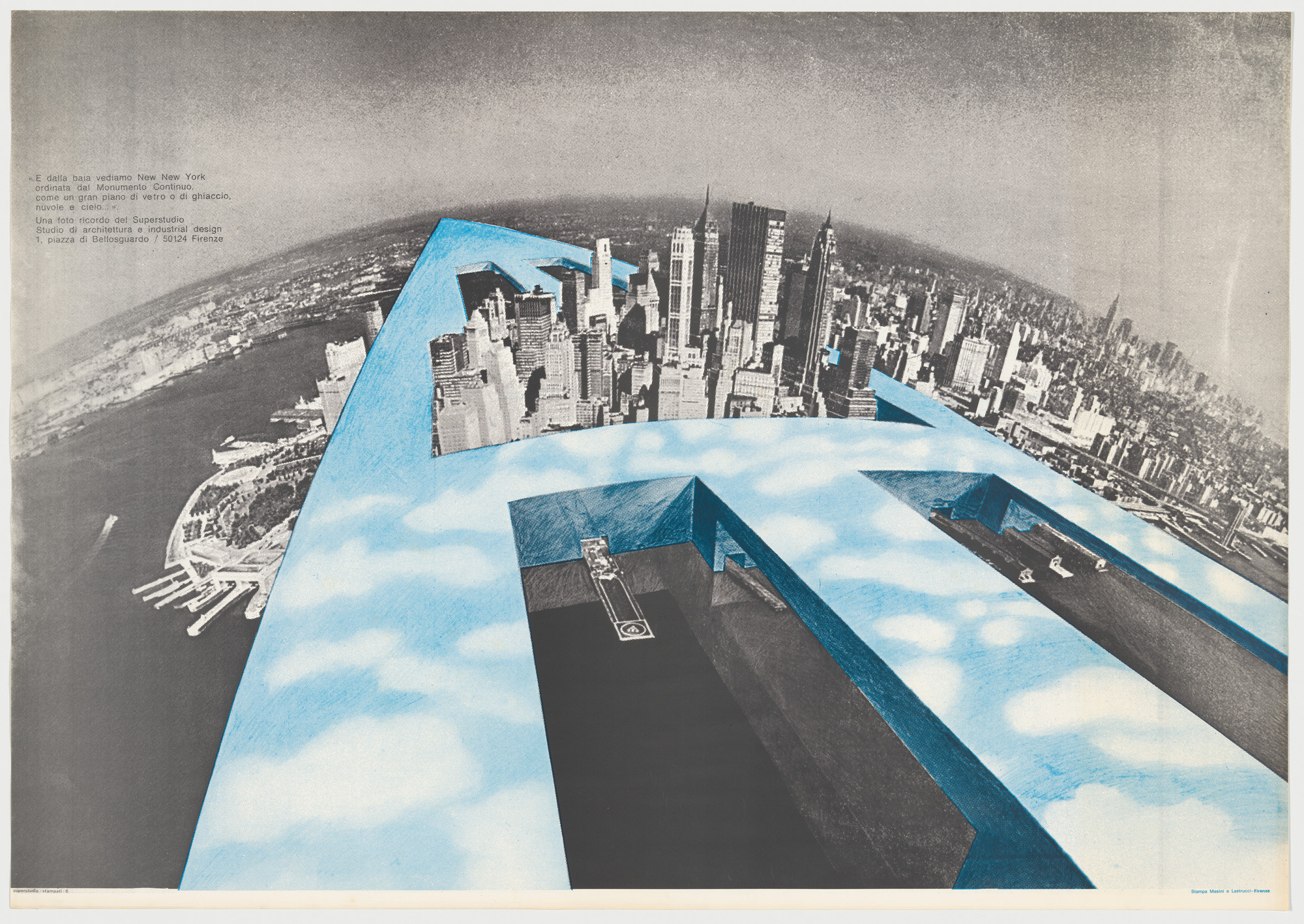

Superstudio was founded by five architects in Florence in 1966, and became the most poetic and incisive group to come out of Italy in the ensuing decade. Their purely theoretical drawings from The Continuous Monument series illustrate their conviction that by extending a single piece of architecture over the entire world they could "put cosmic order on earth." In the urban context, The New York Extrusion extends the city's profile over a section of Manhattan, and grafts nature to it by reflecting the blue sky in tops of the buildings. In the other drawings, there are white, gridded, monolithic structures that span the natural landscape to assert rational order upon it. Superstudio saw this singular unifying act, unlike many modern utopian schemes, as nurturing rather than obliterating the natural world.

Superstudio, Gian Piero Frassinelli, Alessandro Magris, Roberto Magris, Cristiano Toraldo di Francia, Adolfo Natalini. The Continuous Monument: New York Extrusion Project, New York, New York (Aerial perspective). 1969. Graphite, color pencil, and cut-and-pasted printed paper on board. 38 × 25¾" (96.5 × 65.4 cm)

Superstudio, Gian Piero Frassinelli, Alessandro Magris, Roberto Magris, Cristiano Toraldo di Francia, Adolfo Natalini. The Continuous Monument: On the Rocky Coast, project (Perspective). 1969. Cut-and-pasted printed paper, colored pencil, and oil stick on board. 18⅜ × 18⅛" (46.7 × 46 cm)

Superstudio, Cristiano Toraldo di Francia, Gian Piero Frassinelli, Alessandro Magris, Roberto Magris, Adolfo Natalini. The Continuous Monument: On the River, project (Perspective). 1969. Cut-and-pasted printed paper, colored pencil, and oil stick on board. 17¼ × 15¾" (43.8 × 40 cm)

Superstudio, Gian Piero Frassinelli, Cristiano Toraldo di Francia, Alessandro Magris, Roberto Magris, Adolfo Natalini. The Continuous Monument: Alpine Lakes, project (Perspective). 1969. Cut-and-pasted printed paper, colored pencil, and oil stick on board. 18 × 18½" (45.7 × 47 cm)

Superstudio, Gian Piero Frassinelli, Alessandro Magris, Roberto Magris, Adolfo Natalini, Cristiano Toraldo di Francia. The Continuous Monument: St. Moritz Revisited, project (Perspective). 1969. Cut-and-pasted printed paper, colored pencil, and oil stick on board. 16⅞ × 19⅛" (42.9 × 48.6 cm)

Superstudio, Gian Piero Frassinelli, Alessandro Magris, Roberto Magris, Adolfo Natalini, Cristiano Toraldo di Francia, Alessandro Poli. The Continuous Monument: New York, project. 1969. Lithograph. 27 9/16 × 39⅜" (70 × 100 cm)

ETTORE SOTTSASSItalian, born 1917

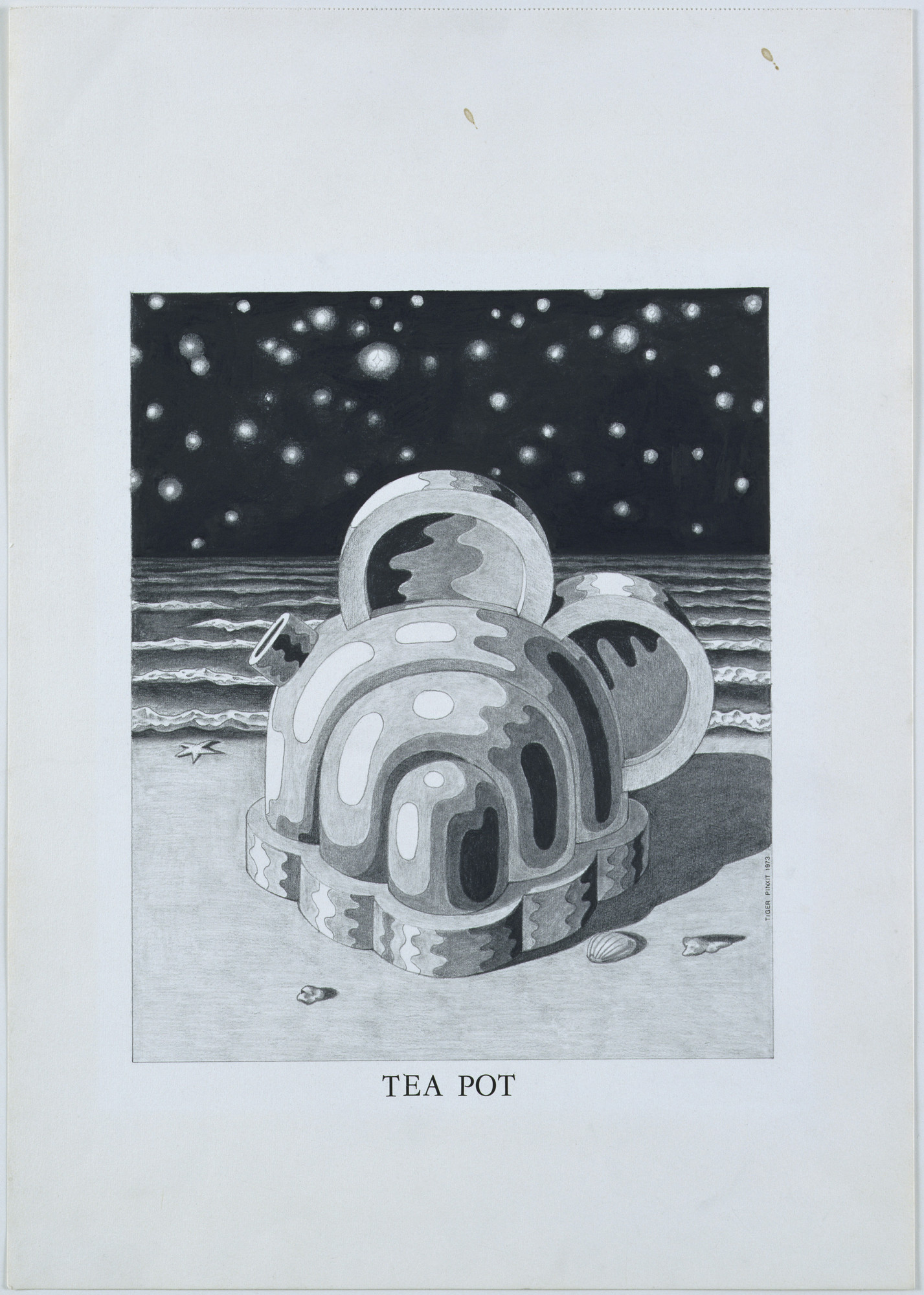

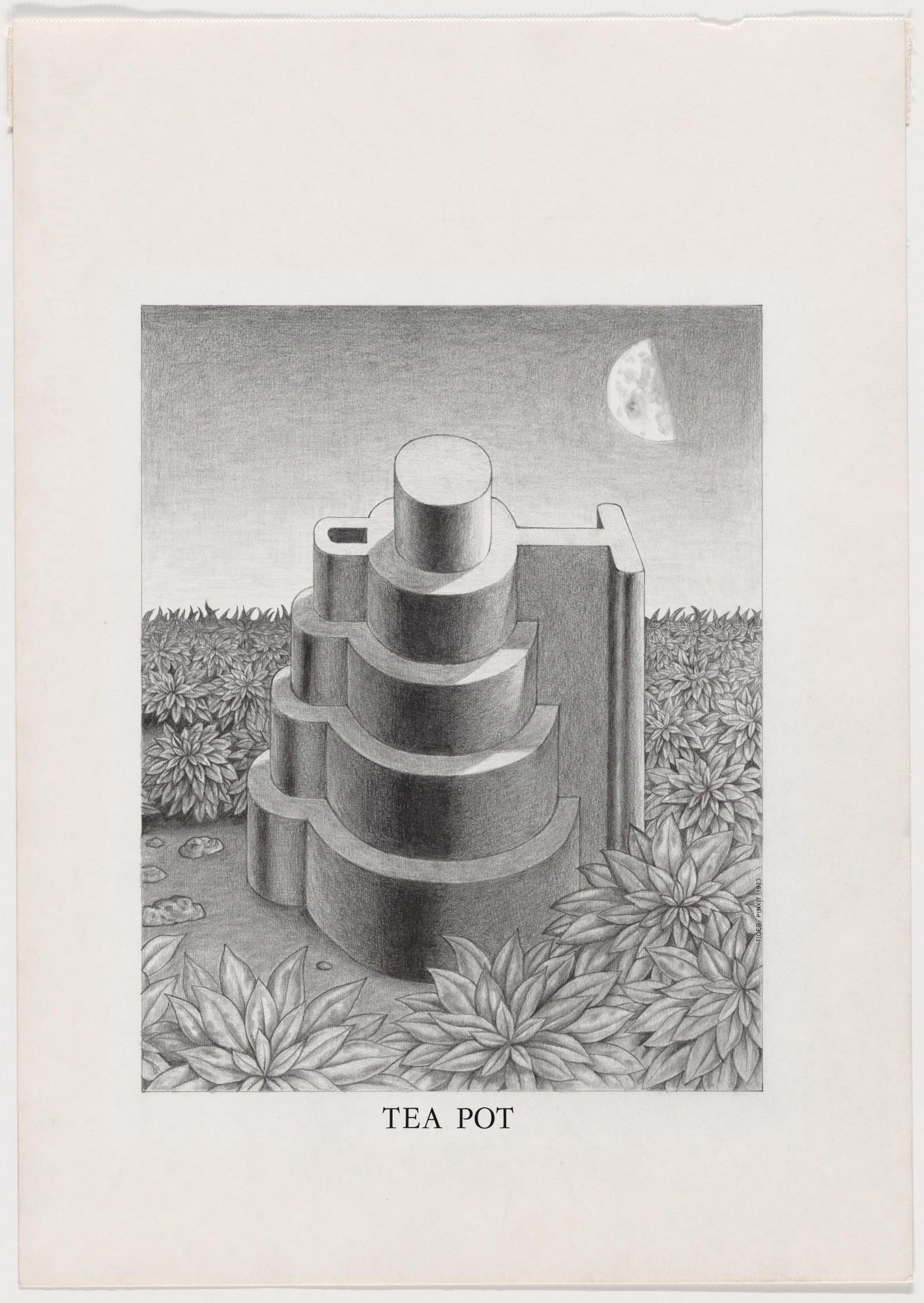

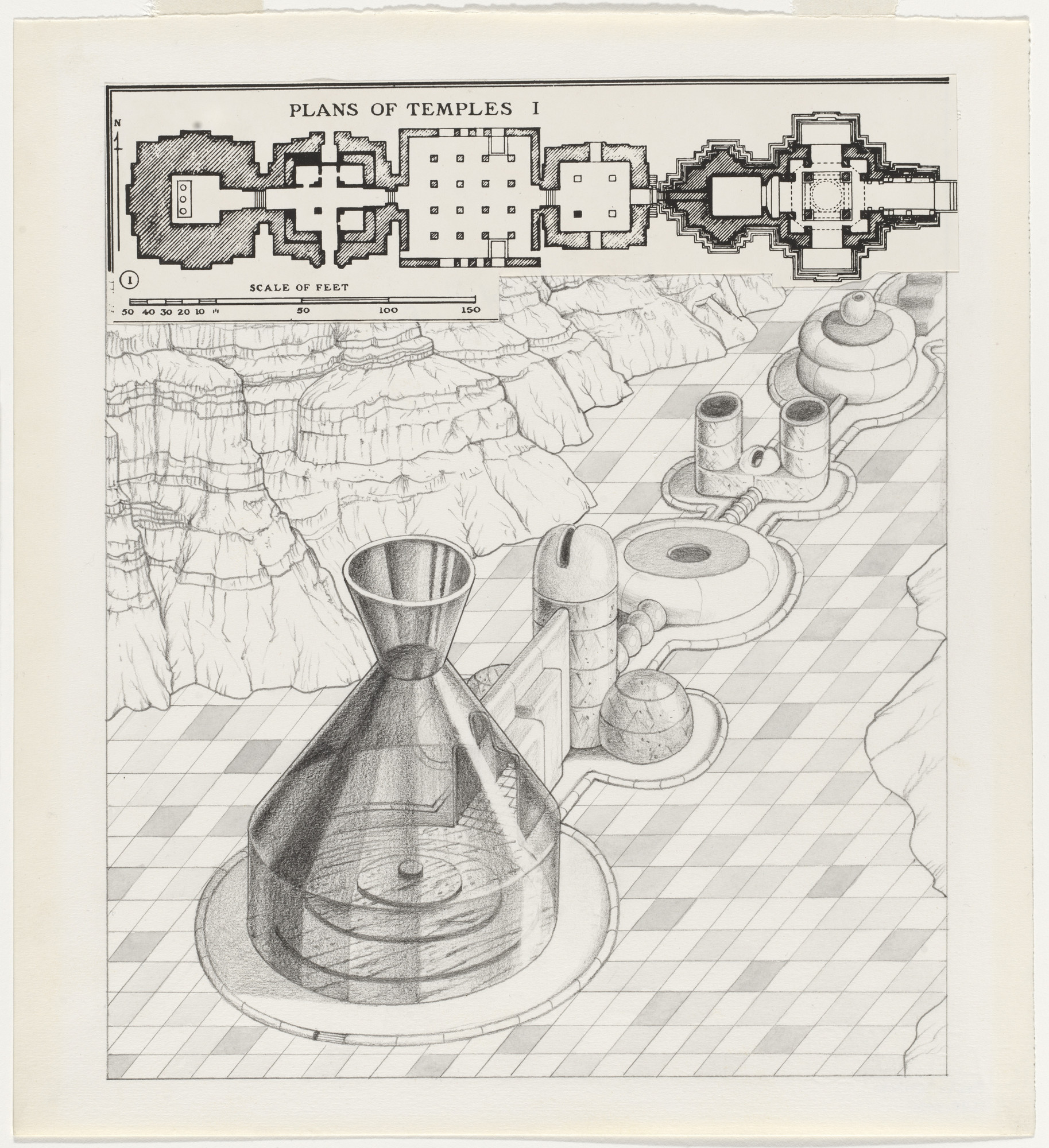

Ettore Sottsass. Study for Tea Pot (by Ocean with Shells), project (Perspective). 1973. Graphite and self-adhesive letters on paper. 19 × 13½" (48.3 × 34.3 cm)

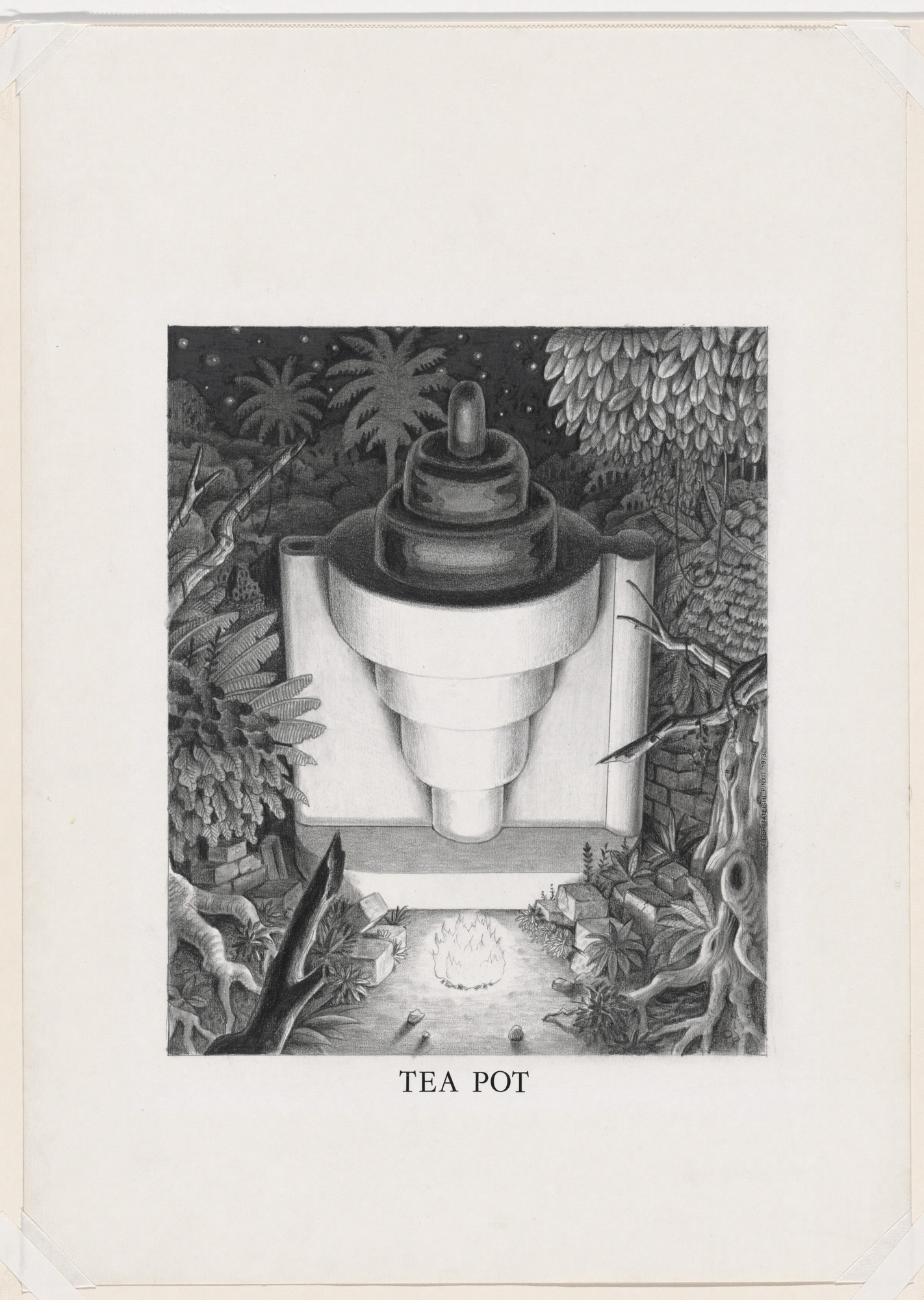

Ettore Sottsass. Study for Tea Pot (in Forest Setting), project (Perspective). 1973. Graphite and self-adhesive letters on paper. 19 × 13½" (48.3 × 34.3 cm)

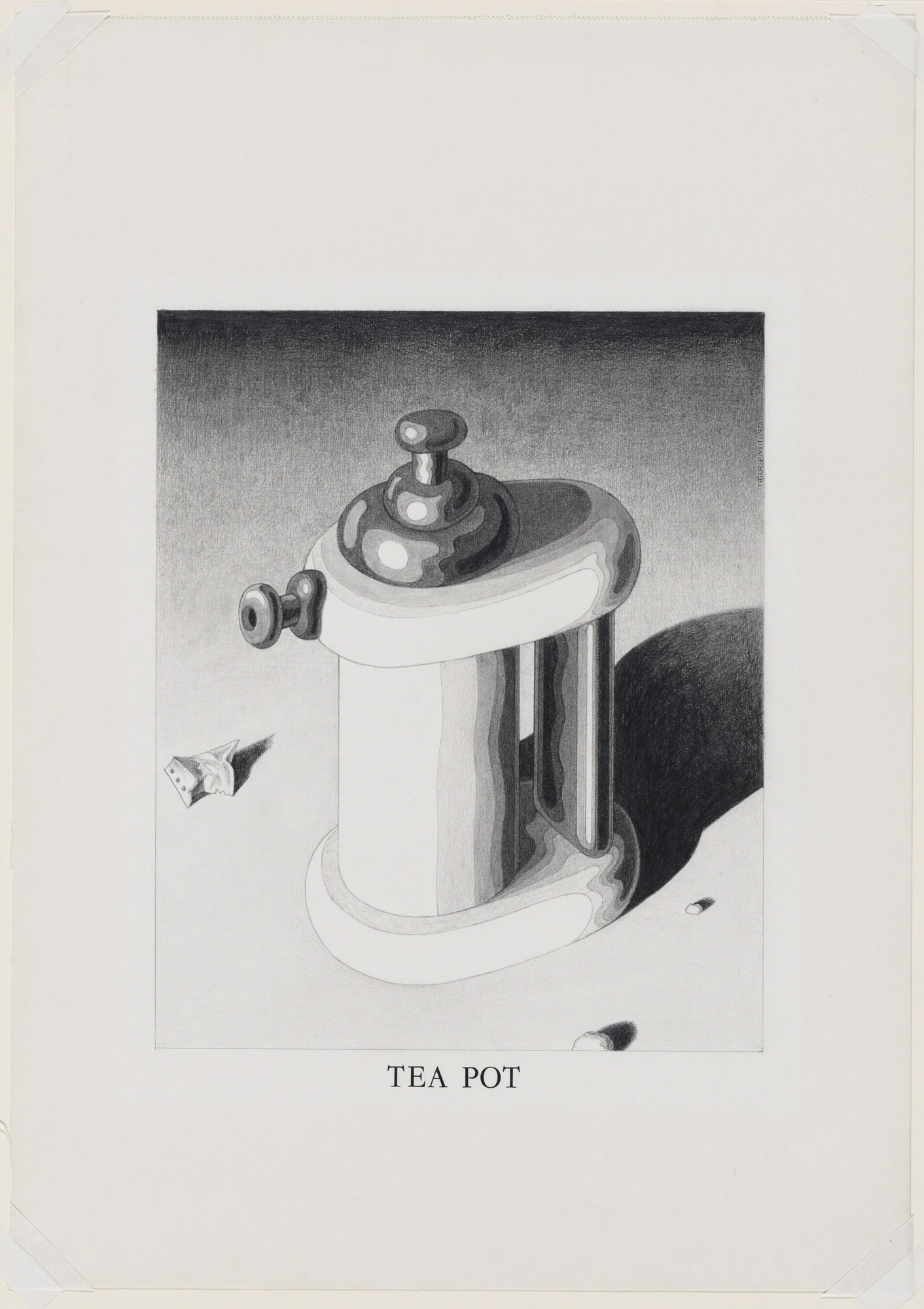

Ettore Sottsass. Study for Tea Pot, project (Perspective). 1973. Graphite and self-adhesive letters on paper. 19 × 13½" (48.3 × 34.3 cm)

Ettore Sottsass. Study for Tea Pot (with Red Lid), project (Perspective). 1973. Graphite and self-adhesive letters on paper. 19 × 13½" (48.3 × 34.3 cm)

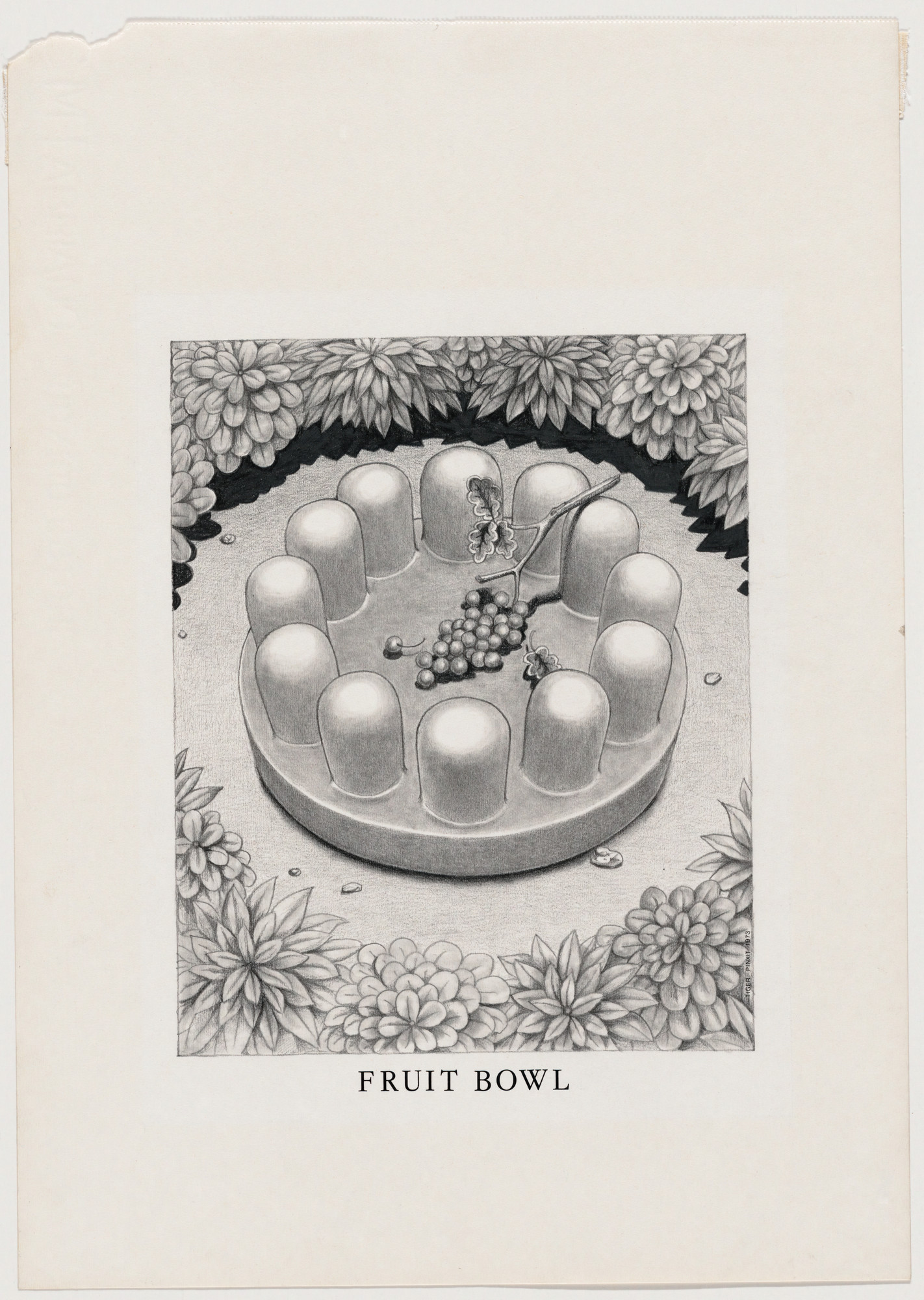

Ettore Sottsass. Study for Fruit Bowl (with Grapes), project (Aerial perspective). 1973. Graphite and self-adhesive letters on paper. 19 × 13½" (48.3 × 34.3 cm)

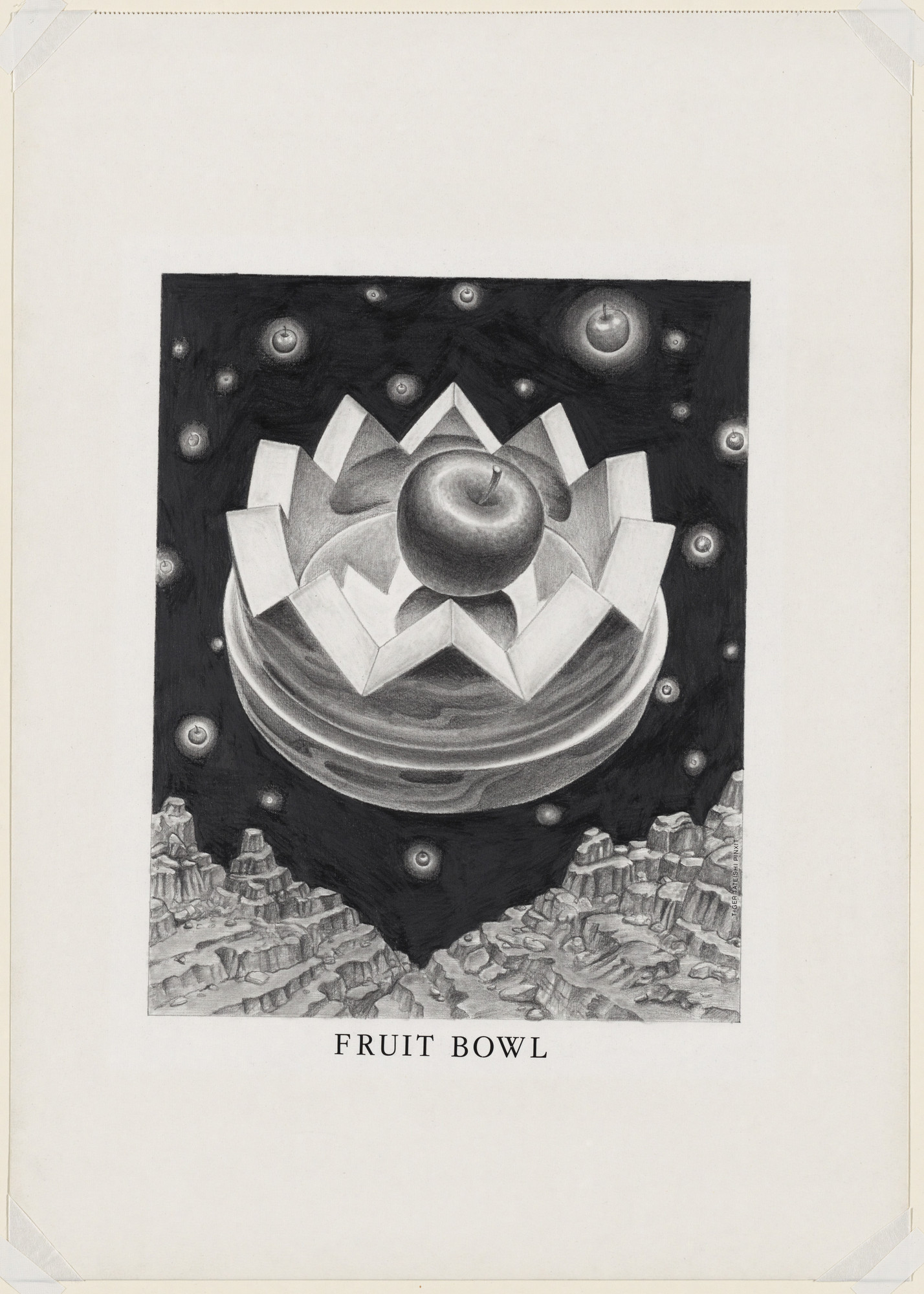

Ettore Sottsass. Study for Fruit Bowl (with Apple), project (Perspective). 1973. Graphite and self-adhesive letters on paper. 19 × 13½" (48.3 × 34.3 cm)

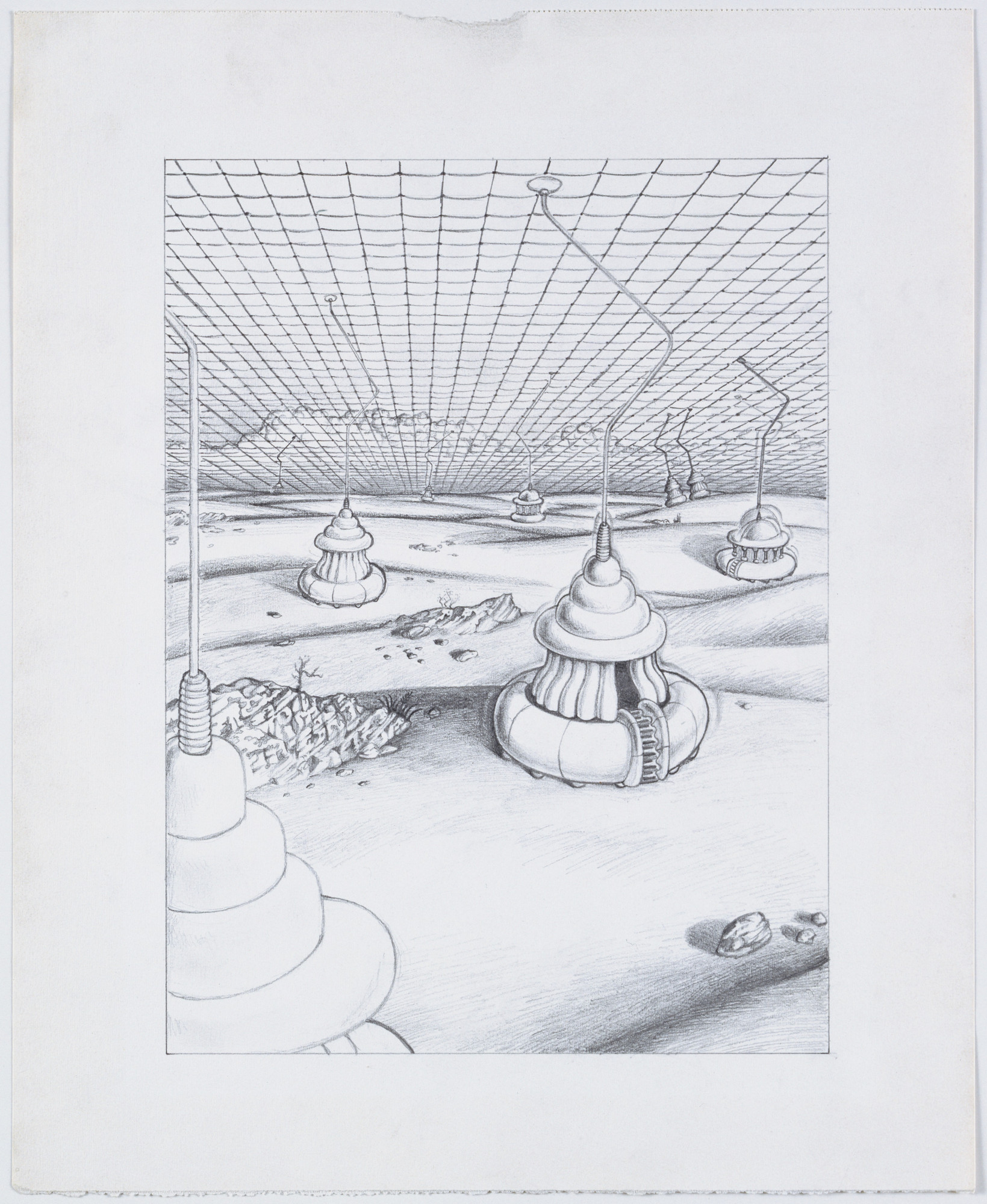

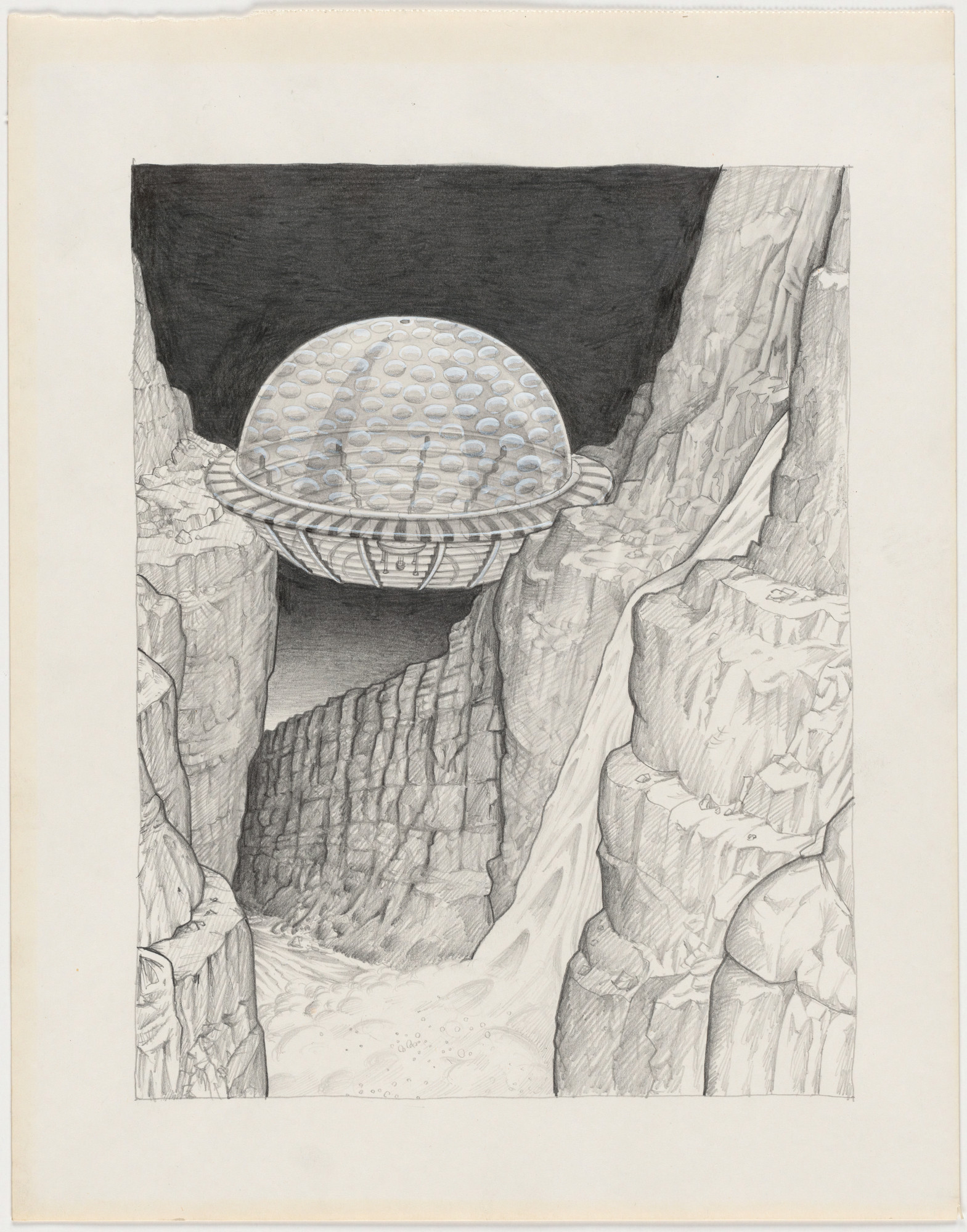

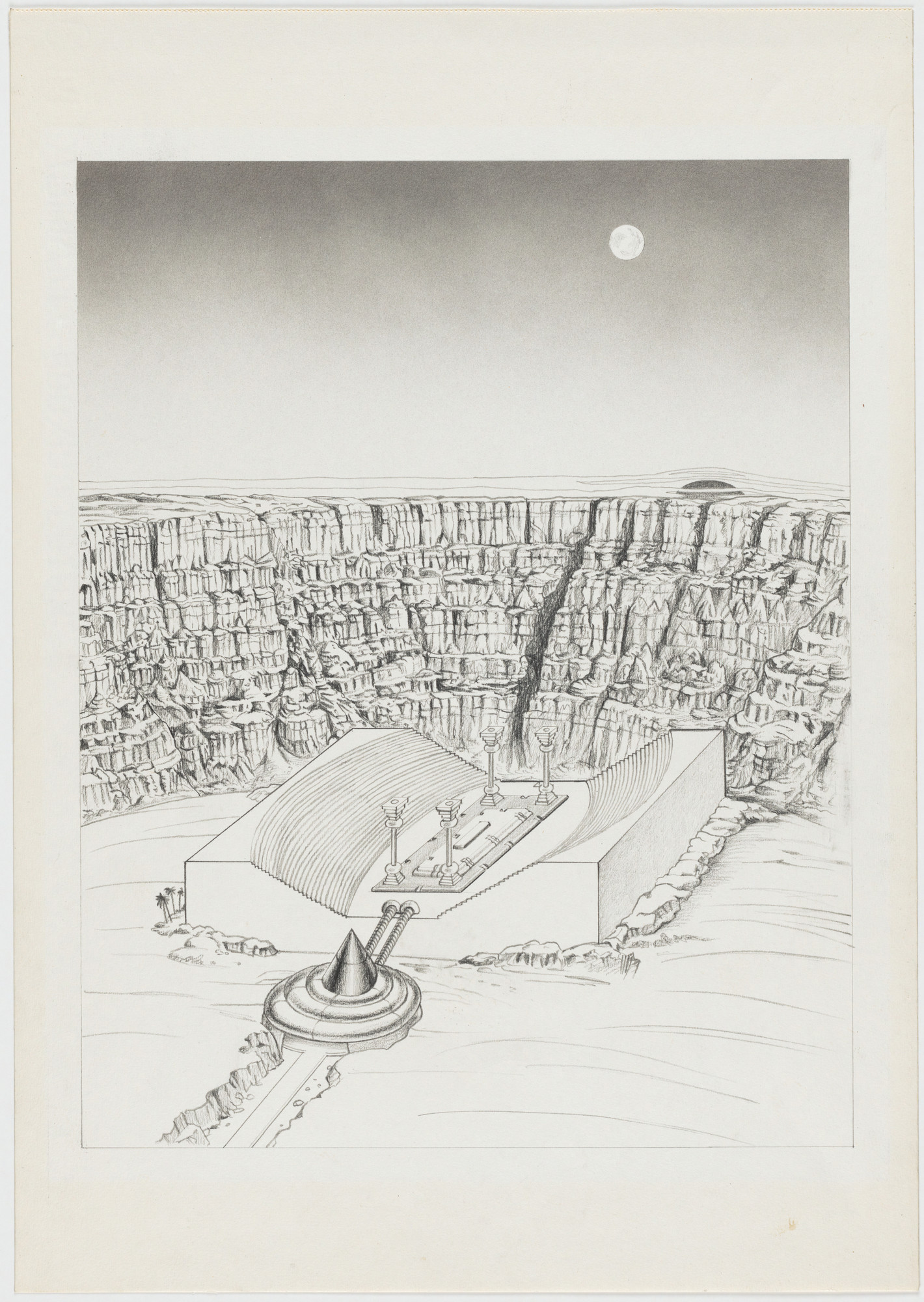

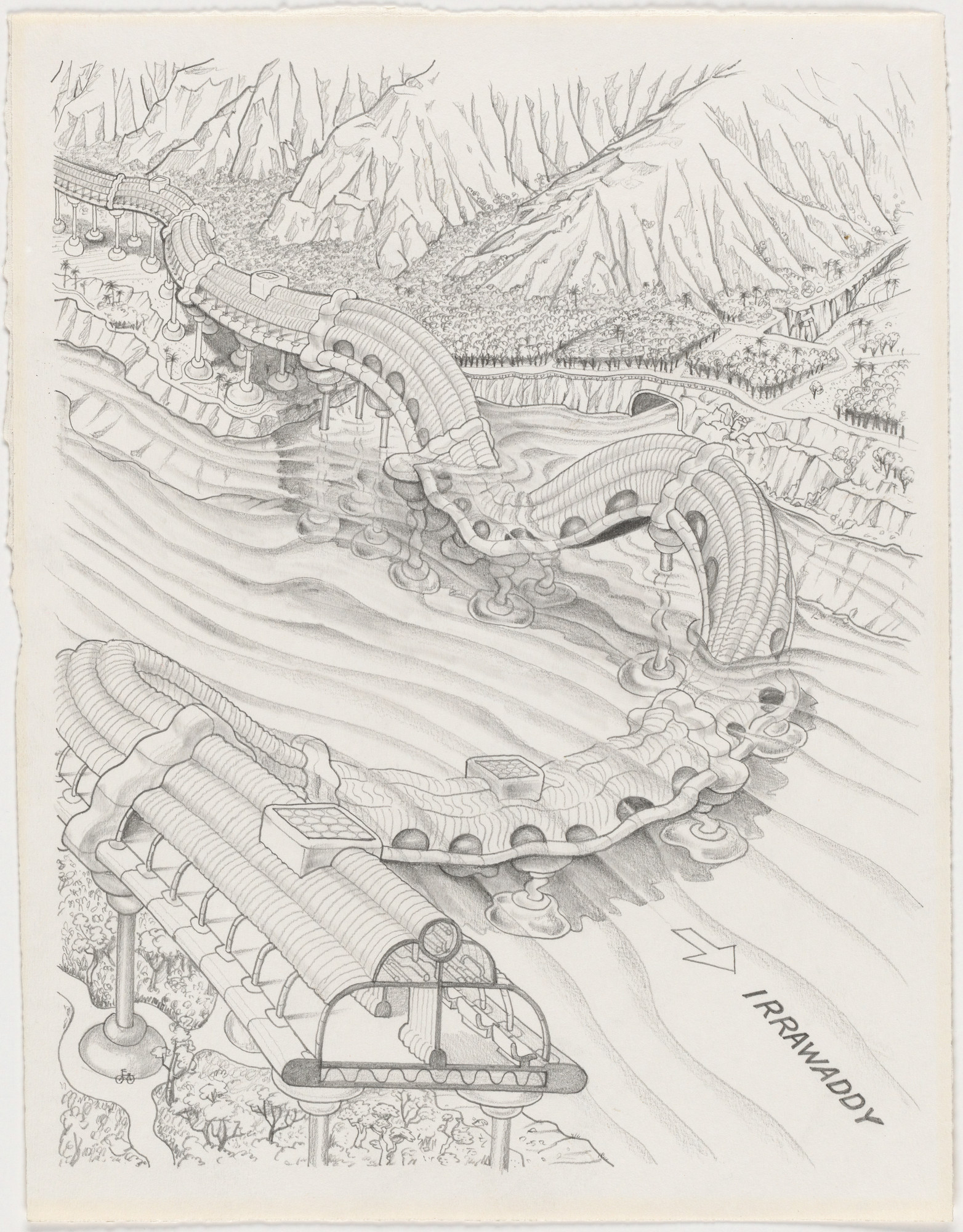

Concerned with the deterioration of urban life, Sottsass used the series The Planet as Festival to depict a utopian land where all of humanity is free from work and social conditioning. In his futuristic vision, goods are free, abundantly produced, and distributed around the globe. Liberated from banks, supermarkets, and subways, individuals can “come to know by means of their bodies, their psyche, and their sex, that they are living,” he said. According to his ideas, once consciousness has been reawakened, technology could be used to heighten self-awareness, and life would be in harmony with nature. Reflecting the counterculture of his time, Sottsass illustrated such instruments for entertainment as a monolithic dispenser for incense, drugs, and laughing gas set in a campground, rafts for listening to chamber music on a river, and a stadium in which to watch the stars.

Ettore Sottsass. The Planet as Festival: Study for a Dispenser of Incense, LSD, Marijuana, Opium, Laughing Gas, project (Perspective). 1972–1973. Graphite on paper. 15⅛ × 13⅜" (38.4 × 34 cm)

Ettore Sottsass. The Planet as Festival: Study for a Large Dispenser of Waltzes, Tangos, Rock, and Cha-Cha, project (Perspective). 1972–1973. Graphite on paper. 16½ × 13⅜" (41.9 × 34 cm)

Ettore Sottsass. The Planet as Festival: Study for Design of a Stadium for Rock Concerts, project (Aerial perspective). 1972-73. Graphite and white ink on paper. 14¾ × 11½" (37.5 x 29.2 cm)

Ettore Sottsass. The Planet as Festival: Study for Design of a Stadium to Watch the Stars, project (Aerial perspective). 1972-73. Graphite on paper. 19 × 13½" (48.3 × 34.3 cm)

Ettore Sottsass. The Planet as Festival: Study for Rafts for Listening to Chamber Music, project (Perspective). 1972–1973. Graphite on paper. 14½ × 12⅜" (36.8 × 31.4 cm)

Ettore Sottsass. The Planet as Festival: Study for Temple for Erotic Dances, project (Aerial perspective and plan). 1972–1973. Graphite and cut-and-pasted gelatin silver print on paper. 13 15/16 × 12⅝" (35.4 × 32.1 cm)

Ettore Sottsass. The Planet as Festival: Gigantic Work, Panoramic Road with View on the Irrawaddy River and the Jungle, project (Aerial perspective). 1972–73. Graphite on paper. 16 × 12¼" (40.6 × 31.1 cm)

Ettore Sottsass. The Planet as Festival: Design of a Roof to Discuss Under, project (Perspective). 1972–73. Graphite on paper. 11½ × 10⅞" (29.2 × 27.6 cm)

17 апреля 2025, 20:47

0 комментариев

|

Партнёры

|

Комментарии

Добавить комментарий