|

|

African Negro art / Edited by James Johnson Sweeney. — New York, 1935African Negro art / Edited by James Johnson Sweeney. — New York : The Museum of Modern Art, 1935. — 144 p., ill.

The artistic importance of African Negro art was discovered thirty years ago by modern painters in Paris and Dresden. Students, collectors and art museums have followed the artists' pioneer enthusiasm. This volume contains 100 plates reproducing sculptured figures and ceremonial masks In wood, bronze and ivory; three maps; a bibliography of 130 titles; descriptions of 600 works of art; and an introduction by the director of the exhibition, JAMES JOHNSON SWEENEY.

THE ART OF NEGRO AFRICA

"Quand les choses n'étaient pas encore, Mébère, le Créateur, il a fait Fhomme avec les terres d’argile. Il a pris Vargile et il a façonné cela en homme. Cet homme a eu ainsi son commencement, et il a commencé comme lézard. Ce lézard, Mébère l'a placé dans un bassin d'eau de mer. Cinq jours, et voici: il a passé cinq jours avec lui dans ce bassin des eaux; et il l'avait mis dedans. Sept jours; il fut dedans sept jours. Le huitième jour, Mébère a été le regarder. Et voici, le lézard sort; et voici qu'il est dehors. Mais c’est un homme. Et il dit au Créateur: Merci.

—Biaise Cendrars: Anthologie Nègre

Today the art of Negro Africa has its place of respect among the esthetic traditions of the world. We recognize in it the mature plastic idiom of a people whose social, psychological and religious outlook, as well as history and environment, differ widely from ours. We can never hope to plumb its expression fully. Nevertheless, it no longer represents for us the mere untutored fumblings of the savage. Nor, on the other hand, do its picturesque or exotic characteristics blind us any longer to its essential plastic seriousness, moving dramatic qualities, eminent craftsmanship and sensibility to material, as well as to the relationship of material with form and expression.

Today, the art of Negro Africa stands in the position accorded it on genuine merits that are purely its own. For us its psychological content must always remain in greater part obscure. But, because its qualities have a basic plastic integrity and because we have learned to look at Negro art from this viewpoint, it has finally come within the scope of our enjoyment, even as the art expressions of such other alien cultures as the Mayan, the Chaldaean, and the Chinese.

Whether or not African Negro art has made any fundamental contribution to the general European tradition through the interest shown in it by artists during the last thirty years is a broadly debatable point. In the early work of Picasso and his French contemporaries, as well as in that of the German "Brücke" group, frank pastiches are frequently to be found. But these, like the adoption of characteristically negroid form-motifs by Modigliani and certain sculptors, appear today as having been more in the nature of attempts at interpretation, or expressions of critical appreciation, than true assimilations. When we occasionally come across something in contemporary work that looks as if it might have grown out of a genuine plastic assimilation of the Negro approach, on closer examination we almost invariably find that it can as fairly be attributed to another influence nearer home. Cézanne’s researches in the analysis of form, to take an obvious example, not only laid the foundation for subsequent developments in European art but also played an important part in opening European eyes to the qualities of African art.

In any case, it remains a fact that, about the year 1905, European artists began to realize the quality and distinction of the Negro plastic tradition to which their predecessors had been totally blind, and that the conditions which had prepared them for this realization had been at the same time laying the foundations for a freshened European plastic outlook.

In those first years there had been practically nothing yet written on the subject. This fact in itself had an appeal for the younger painters of the time, tired of traditions so overlaid with literature that an approach on purely plastic grounds was difficult. Anthropologists and ethnologists in their works had completely overlooked (or at best had only mentioned perfunctorily) the esthetic qualities in artifacts of primitive peoples. Frobenius was the first to call attention to African art. But his articles Die Kunst der Naturvölker in Westermann's Monatshefte (Jahrgang XI, 1895-6); and Die Bildende Kunst der Afrikaner in Mitteilungen der anthropologischen Gesellschaft in Wien, 1897-1900, treated the subject primarily from non-esthetic viewpoints. It was not the scholars who discovered Negro art to European taste but the artists. And the artists did so with little more knowledge of the object’s provenance or former history than in what junk shop they had been lucky enough to find it and whether the dealer had a dependable source of supply.

Of course many examples were to be found in ethnographical museums but usually lost in a clutter of other exhibits, since their esthetic character was of no interest to their discoverers or possessors at the time. One has only to look over the priced catalogs of W. D. Webster, an auctioneer of ethnographical specimens located in Bicester, Oxford, to realize how little regarded during the years between 1897 and 1904 were those pieces we recognize today as among the most important in collections such as that of the Museum für Völkerkunde, Berlin. Travellers, traders, and soldiers brought objects back to Europe as curiosities. And when the material of which they were made had no value of its own, they eventually fell into the hands of dealers in ethnographical specimens or, as more often occurred, those of curiosity dealers.1 And it was in these curiosity shops that the first amateurs in France and Belgium made their acquaintance with Negro art.

____________

1 Unfortunately, gold objecte or wooden figures covered with gold leaf (as were most of the wooden statuettes in the gold-bearing regions originally) were melted down or stripped for their metal. In No. 144 we have an example of a wooden statuette covered with thin leaf gold which was recently brought back from the Aitutu tribe of Ivory Coast. Moat of the finer small Ivory Coast figures were probably adorned in this fashion before they fell into European hands.

At first no one heeded the vogue commercially. But gradually as it began to spread and the supply, which was always extremely limited, dwindled, dealers began to take steps to assure themselves of importations. At first the liquidation of estates of old soldiers who had taken part in punitive expeditions against the natives (particularly in England whose African forces had reaped a harvest of Benin bronzes) helped to keep the demand satisfied. Traders then took steps to ship to Europe whatever they could prevail on the natives to part with. However, even in Africa the supply was small: fine pieces were no longer being produced due to the decadence of the natives following their exploitation by the whites. Soon the traders were reduced to employing natives to manufacture copies for the market. And when this in turn failed to satisfy the demand, white forgeries that soon outdistanced the native copies in "character" began to be turned out on a quantity production scale in Brussels and Paris.

Today save for some rare, hitherto unexploited regions,2 art as we have known it in its purest expression no longer comes out of Africa. So while African art on one hand may be considered modern since very few of the examples we possess, due to the highly perishable character of their material in a tropical climate, could have survived more than a century and a half (excepting of course the Benin bronzes and the terra cotta heads dug up in the neighborhood of Ifa), on another, we may say, the art of Africa is already an art of the past.

____________

2 Last year Dr. Himmelheber of Karlsruhe brought back several extremely fine objects from the Ivory Coast, mainly from the Aitutu and Guro tribes. Among these objects are the masks, and the gold objects lent by tbe Forschungsinstitut of Frankfort (Nos. 144-160).

But although the greater part of Negro art which we possess is of comparatively recent production, there is no doubt of the antiquity of the tradition. The collection of Armbraser and Weickmann now in the Museum of Ulm in Germany, contains ivories and weapons brought back to Europe before 1600. And since the middle ages we have heard tales from travellers and explorers of kingdoms along the Gulf of Guinea and to the south of the Sahara which in the telling seemed fabulous. Nevertheless, though details were exaggerated, there is sufficient dependable evidence to establish a basis for their accounts. And while the actual sculptures we know are modern, traditional models on which they are based have no doubt been handed down within the tribes for generations.

Long before the Portuguese, encouraged by Prince Henry the Navigator, had actually reached Great-Benin in 1472, or Oedo as the capital was called, we have reports of other great Negro kingdoms to the north and west. In the early XlVth century some Genoese seamen had already worked their way round the west coast of Africa considerably beyond the Canaries; and in 1364 a party of Dieppe sailors are reported to have gone as far as what is probably the Gold Coast today. But it was usually from travellers in the interior and from traders that the more striking descriptions came; for example, of the great negroid kingdom of Ghana which in the Xth and XIth centuries3 extended from Senegal across the bend of the Niger; of Melle the successor to Ghana in the XIIIth and XIVth centuries; and of the Songhai empire of Gao which rose from the ruins of Melle to touch the zenith of its power in the XVIth century when it extended from Lake Chad to the Atlantic. To the north lay the Hausa states which grew out of the seven towns of Biram, Gober, Kano, Rano, Zaria, Katsena and Daura, and were originally peopled by a Negro race, apparently related to the early Songhai. These original inhabitants were conquered in the Xth century by another people from the east of obscure affinities. And these conquerors in their turn founded an empire which survived (with intervals such as the conquest by the Songhai in 1512 and by the Moors in 1595) until they were subjected by the Fula in 1807. Further south along the coast lay the kingdom of Yoruba. At its height it comprised the whole region between the middle Niger and the Gulf of Guinea and that between the lower Niger on to the east as far as, and including, Ashantiland on the west. And among the native civilizations of Africa it is with reference to an outgrowth of Yoruba, the kingdom of Great-Benin, that we possess the fullest documentation.

____________

3 Even dating back to tbe Vth century according to some authors such as Delafosse in "Les Nègres," Paris, 1927, founded as he believes about 300 A.D. by a Judaeo-Syrian colony from which by miscegenation with the natives the Fula race sprang.

And while this is not really extensive or even historically exact, the fact that we have some actual information on Benin has inclined us to lay an undue importance on its culture in comparison with the other great kingdoms and empires regarding which we are entirely without data beyond the evidence of their artistic genius which some surviving sculptures may offer. This particular road to false valuations the earliest amateurs and artists hoped to avoid through an exaggerated disinterest in the historical and ethnographical sides of African art. But, properly considered, the few facts we have about Benin should help to dissipate the idea that Negro art is a chance production of a people entirely lacking in culture or sense of social organization. And with the products of other lesser known cultures before us to speak for themselves, there should be no likelihood of abusing the approach.

As we saw, the Portuguese were the first Europeans to reach Benin. The chronicler Jâo de Barro tells us that Alonso d’Aveiro who visited Great-Benin in 1472 brought back a native ambassador with him to the court of Portugal. The brothers de Bry, about 1600, following the description of a certain mysterious Dutch traveller, D. R., give the first details regarding the capital, which lay about seventy-five miles inland from the mouth of the Benin or Formosa River. The main street of the city, according to them, was seven or eight times wider than the great street of Amsterdam, and stretched out of sight in the distance. Somewhat later, in 1668, Dr. Olfert Dapper describes the wealth and importance of the city. It was then fortified by a solid rampart ten feet high. A like wall protected the royal palace, "which," as Dapper’s informant added, "was as large as the whole city of Harlem." The magnificent structures which composed it were linked together by long impressive colonnades of wooden pillars covered from top to bottom with bronze plaques depicting battle scenes. Thirty broad streets then ran the length of the city, each lined with carefully constructed houses. The dwellings were low but large, with long interior galleries and numerous rooms, the walls of which were made of smooth red clay polished till it gave the appearance of marble.

A century later, in 1704, another traveller named Nyendael found the city in ruins,—scarcely inhabited. The corridors of the palace were now supported by wooden pillars so rudely carved that the chronicler was scarcely able to discern what was represented. There was no longer any evidence of the bronze plaques which had formerly attracted so much attention. And it may now be supposed, since no traveller following Nyendael makes any mention of them despite their extraordinary character, that during the civil war which ravaged Benin in the last years of the XVIIth century they had been hastily pulled down and hidden in the storehouses where the British found them in 1897.

In the course of the XVIIIth century the city rose again from its ruins. However, it never regained its ancient splendor. And in 1820 the palace was again destroyed during an insurrection.

It was not until 1897 that the first bronzes from Benin reached Europe. The British since 1851 had been established at Lagos. Later, in 1897, the British consul Philipps attempted to enter the capital of Benin during a religious festival and in spite of the royal prohibition. He and his party were killed. And the British immediately took advantage of this excuse to despatch a punitive expedition which resulted in the complete destruction of the capital.

However, before their fires had gutted the city the invaders managed to strip the palace of its bronzes and plunder the storehouses. The bronzes and ivories were shipped back to London either as curiosities or scrap. And as we have seen, soon appeared on the market through channels such as Webster, the Oxford auctioneer, or curiosity dealers in England and on the Continent.

The quality of the pieces both artistic and technical at first mystified Europeans. At the tune Africa was held to be the "dark continent" as much in its unenlightenment as in the color of its natives. The natives were considered "savages" and their productions hitherto of no interest to Europeans save as illustrations of their barbarism, or at best as souvenirs of a stay in their country happily terminated. When these bronzes appeared, of which von Luschan has said "Cellini himself could not have made better casts, nor anyone else before or since to the present day," an explanation had to be found. The casts in all cases had evidently been produced by the difficult "cire perdue" method. And although this procedure permits only a single proof, to the Europeans of the time expecting nothing the product seemed numberless. Further, the "cire perdue" technique which may seem simple in a summary explanation,4 presents extreme difficulties in execution and requires a thorough familiarity and a technical cleverness which comes only of long practice. Till a representation of figures in Portuguese garb was discovered on certain of the plaques no explanation of the origin of the native knowledge of the process could be offered. Then the explanation seemed obvious: the Portuguese had imported the method. To bear out the theory, an English researcher managed to discover a so-called local tradition to the effect that one Ahammangiva, a member of the first party of white men to set foot in Benin, in the reign of Esige, had introduced bronze casting.

____________

4 In casting by the "cire perdue" method the sculptor prepares a model of wax over an earthen core. The wax model is then covered with numerous thin coats of fine potter’s clay in a completely liquid state. Each coat is allowed to dry separately. When the coats offer a satisfactory thickness, the whole is enveloped in earth, which solidifies in drying. When sufficiently dry, the whole is heated. The wax with heating naturally melts and escapes through vents arranged for that purpose. Molten metal is then poured in through these holes and takes the place left empty by the melted wax. After cooling, tbe mould is broken, reproducing with most exact precision what the artist had originally modelled in wax.

However, since the beginning of the century, other discoveries have brought this theory into question. A better knowledge of African history, an analysis of the stylistic features of the Benin production which shows it to be fundamentally negroid and, finally, the discoveries made by Frobenius during his excavations at Ifa5 lead us to believe today that Great-Benin inherited its strange civilization through the ancient realm of Yoruba from the Sudanese empires which were constantly in touch with Egypt.

____________

5 Plaster casts Nos. 292-302 lenL by the Forschungsinstitut of Frankfort reproduce five of the terra cotta heads which, together with one in bronze, were discovered by Prof. Leo Frobenius during his excavation at Ifa in British Nigeria in 1910. The original heads are now in the collection of the Museum für Völkerkunde in Berlin and are probably the most ancient examples of African Negro sculpture we possess. As may be noted, they bear a striking resemblance to the oldest bronze heads of Benin. And in view of the close relations existing between these adjoining regions, it would not be surprising if the Ifa heads had furnished tbe model for those of Benin. The first kings of Benin came from Ifa and continued long after to recognize its religious authority. The art of casting, it is now held, was understood in Yoruba before it reached Benin. And we know that it was usual for the high priest of Ifa to send a bronze head to each new Obba (king of Benin) on the occasion of his coronation.

Despite the greater weight of historical data we possess in regard to the kingdom of Benin, the chronology of its artistic production is still almost as uncertain as that of other regions. Yet we can feel considerable justification in setting the date of the production of the finest bronzes earlier than the decadence which set in after the civil war in the latter part of the XVIIth century. And the material of which the greater part of the Benin objects is constituted is not so perishable as that of the objects from other regions so could easily have survived for several centuries. Again we have certain ivory pieces in Ulm brought back to Europe before 1600 which offer a basis, slight as it may be, for stylistic comparisons.

The German ethnologists von Luschan and Struck have essayed to date the bronzes by a system of reference with the royal chronology of Benin which goes back to the foundation of the capital in the XIIth century. However, such a classification seems rather unsure. And precision will probably not be possible until scientific excavations on the site of Benin itself have been carried out.

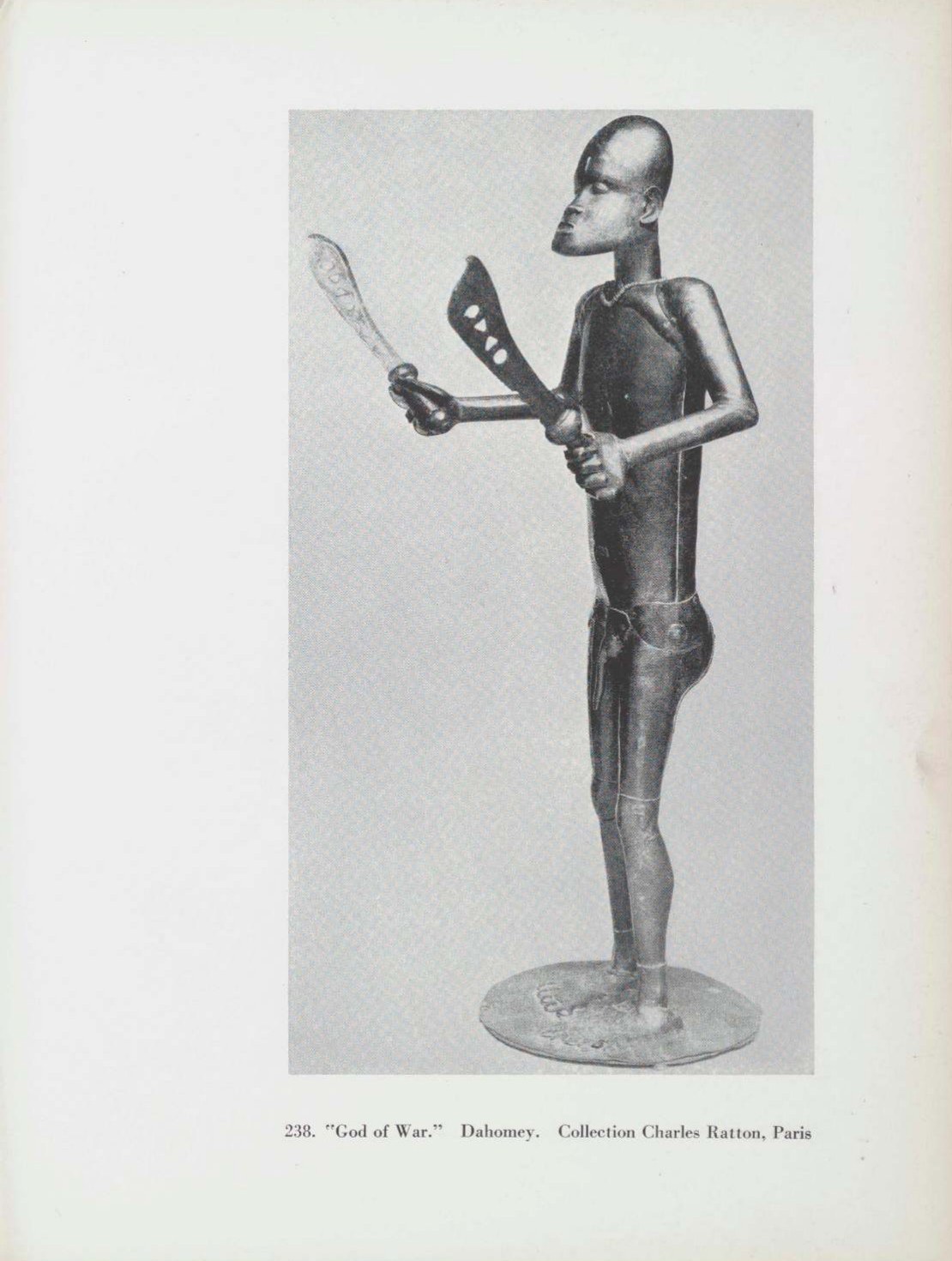

Thus we can see that an historical consideration of African art still remains its least rewarding facet. A summary review however of what we know of Benin, the most powerful kingdom of the Guinea coast over a long period, how it was influenced by Yoruba and in turn exerted its artistic influence over such neighbors as Dahomey, Abomey and Zanganado, gives us a notion of what may have been the culture and power of those greater empires of Melle and Ghana in the north and Lunda in the region now described as Belgian Congo of which we know even less than of Benin. Also it helps us to envisage, at least in part, the standard of culture that doubtless obtained there and its results: a seemingly general prosperity; large populous cities; extensive areas of land under cultivation; and orderly, peaceloving inhabitants keenly sensitive to beauty in their environment, habiliments, and art. And, finally, we may agree with Frobenius who observed that the legend of the barbarous Negro current in Europe during the latter half of the XIXth century is primarily the creation of European exploiters who needed some excuse for their depredations.

The regions concerning the past of which we possess any information (even if only tradition handed down orally) make a very small part of the vast area of central and west Africa producing objects which may be said to offer predominantly negroid characteristics. On the other hand, when we consider the large areas drawn upon, the production seems incredibly small.

For while the finest work from a sculptural viewpoint may be considered as the product of the Negro proper, the area of production embraces the greater part of that region in which the Negro peoples, both Negroes proper and Bantu, predominate in the population. To describe roughly this area, a northern boundary might be drawm from the Atlantic Ocean on the west at the mouth of the Senegal, eastward through the upper bend of the Niger across to Lake Chad, southeast to the upper shores of Lake Victoria Nyanza and from there along the northern border of Tanganyika to the coast. The southern boundary may be said to follow that of the Belgian Congo province of Tanganyika westward, across southern Angola to the Atlantic.

The popidation of the African continent may be divided into five main stocks: Libyan, Hamite, Himyarite (Semite), Negro and Bushman, exclusive of the modern European population and the Indians and Chinese introduced by them.

The question of the peopling of Africa, the migrations and interminglings of the original stocks, is a difficult one and in the present state of our knowledge it is only possible to put forward a tentative theory.6

____________

6 British Museum Handbook to Ethnographical Collections. Refer pp. 191—194 for a fuller discussion from which following paragraphs in main are drawn.

Africa has a central region of dense forest which covers the area drained by the northern tributaries of the Congo and the lower portion of its southern tributaries, and extends along the west coast nearly as far as the Senegal River. Northeast and south of this forest area is a wide region of parkland bordering two deserts—the Sahara to the north and the Kalahari to the south. And since the Negro is primarily an agriculturist, it would seem likely that the cradle of the race was somewhere in the neighborhood of the great lakes.

The race expanded rapidly and without interference until the arrival in Somali-land of the Hamites, a purely pastoral people who crossed over in several migration waves from Arabia. In this way pressure was applied from the east and the Negro stock was forced into the marshes of the Nile Valley and along the open country north of the forest to the west coast, where Negroes of the primitive type are still to be found.

After the Hamites had expelled the Negroes from the "Horn of Africa" one of their pioneer branches, already containing a tinge of Negro blood, found its way south down the eastern strip of parkland and mingled with the Bushmen to form the Hottentot people. However, the route to the south was soon closed by the Negroes and the tribes of mixed blood to which the contact between Negro and Hamite gave rise. Such tribes received no recognition from the true Hamites among whom purity of blood was a matter of highest importance. They were therefore forced to cast their lot with the Negroes. The result was that their Hamitic physical traits became almost totally merged in those of the Negro, since the element of Hamitic blood was so slight when diffused among such a large number of Negro tribes. In this way arose the first Bantu tribes, who seem to approach the Hamites in those points in which they differ from the Negro proper.

Gradually the weaker peoples Bushmen, Pygmy, and Tuareg, were driven into the desert or the heart of the forest. And during the last two thousand years we find the Negro peoples inhabiting mainly the less dense regions of the forest, the forest skirt and the parklands of west and central Africa.

Tribal expansion was the prime stimulus to migration. But we find also another cause among the Negroes: a craving for salt with a concommittant desire to control the sources of its supply. As a result, in west Africa there was a continual movement of tribes toward the sea, where this commodity might be most readily obtained. Naturally this continuous movement had its effect in disseminating tribal traditions. And in the art productions of the Negro peoples the difficulty in allocating stylistic traits with certainty to definite regions or tribes may be in great part attributed to it.

The cultures of the inhabitants of different types of country were also bound to vary with the different conditions of environment. For example, the large states and federations such as Melle, the Hausa, Yoruba and Lunda were all outgrowths of parkland and forest edge conditions where communication was not difficult. In the denser forest central control of a wide area was impossible and each village remained independent. Architecture in the dense forest areas consequently never received the attention accorded to it in the large capital cities.

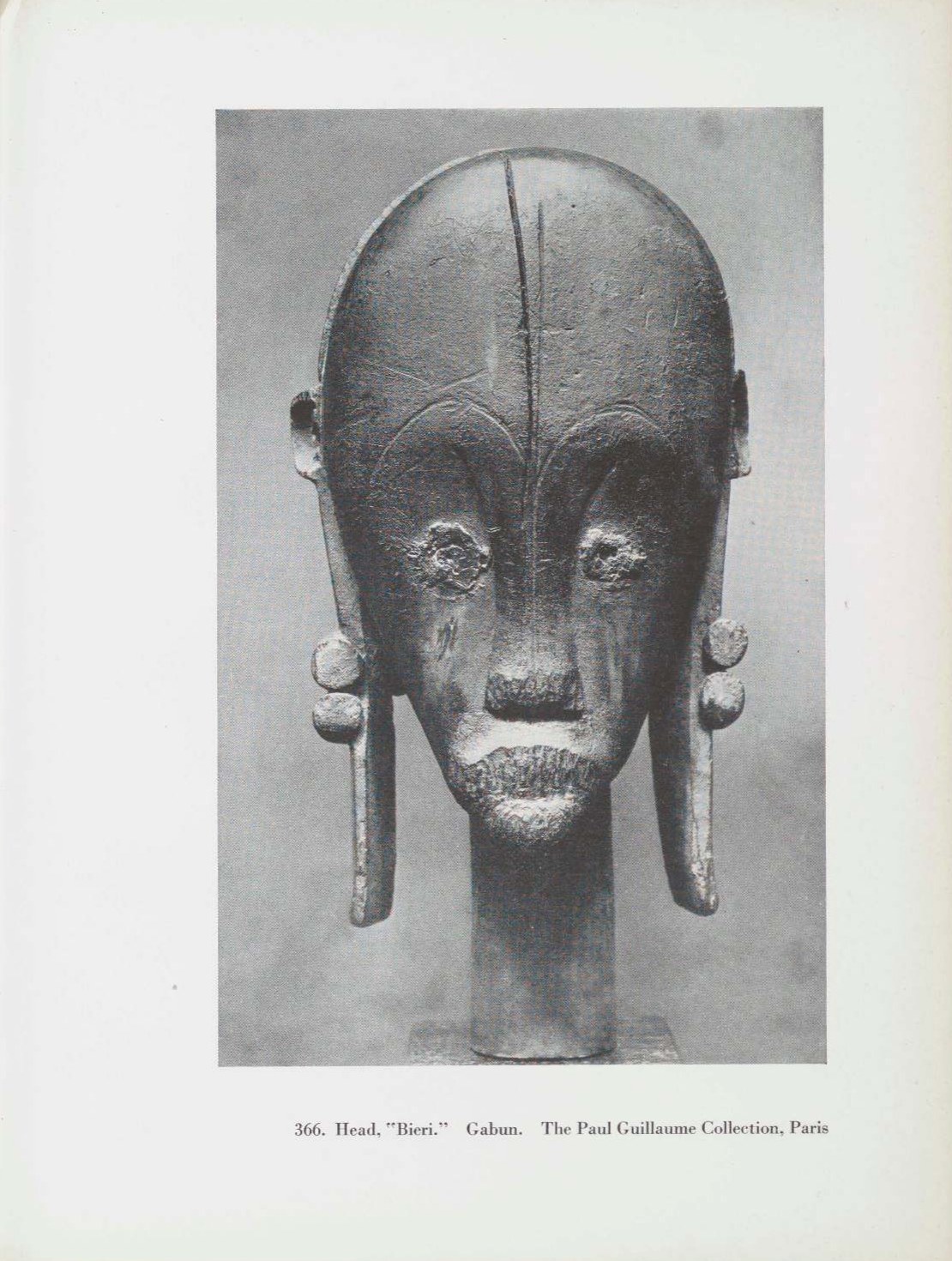

Their type of religion, also determined in great part by environment, we find particularly reflected in their art. Ancestor-worship is elaborated primarily among peoples who through seeing men wielding great power in this world come to feel that the souls of the great should still be powerful after death. This is the cult that in many regions of Africa has been productive of the finest sculpture, not only through symbolizing the dead as in the stylized burial fetishes of the Ogove River district in Congo (Nos. 378-387), but also through actual portraits. Without doubt many of the ancestor figures of Sudan, Benin and Congo fall into this category. For example, the famous royal statues of the BaKuba kings which the English ethnologists Torday and Joyce found in Belgian Congo and felt could be dated with confidence on the basis of their portrait character. They were clearly individualized in feature—evidently intended as realistic portraits though somewhat altered in keeping with the plastic conventions of the region—and recognized by the natives as representing certain rulers still known and reverenced by name.7

____________

7 The British Museum collection contains three of these figures. The Musée du Congo Belge at Tervueren two. And one until recently was owned by a Belgian private collector named Renkin. Torday and Joyce set the date of the earliest of them about 1600.

Ancestor worship is practically confined to the parklands and the forest edge. In the denser jungle where the tribes are split up, we find little evidence of it. There, animistic beliefs predominate. Trees, streams, rocks, even animals, take the character of minor supernatural forces and have their cults celebrated by rituals in which sculptured masks and fetishes play an important part.

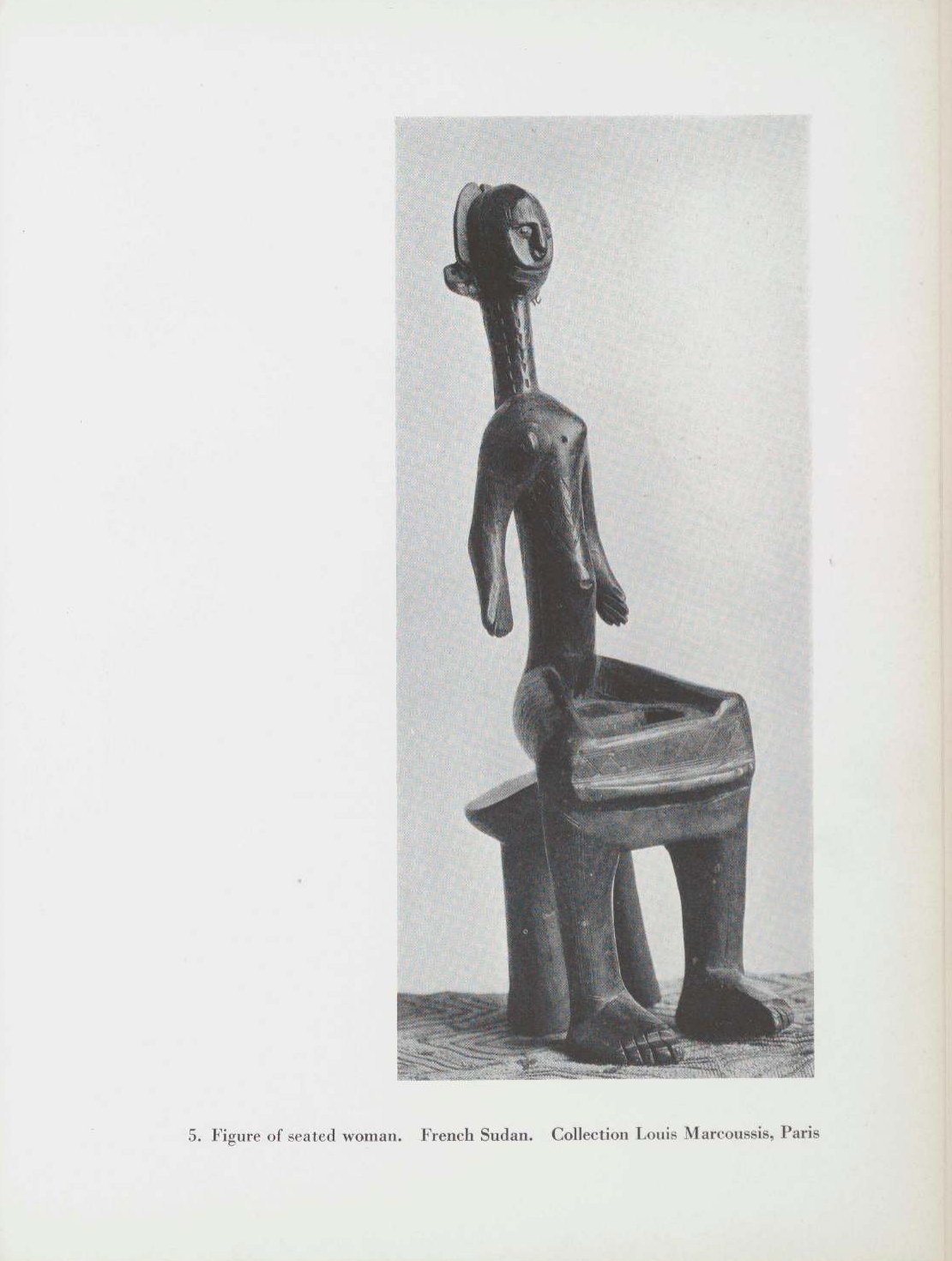

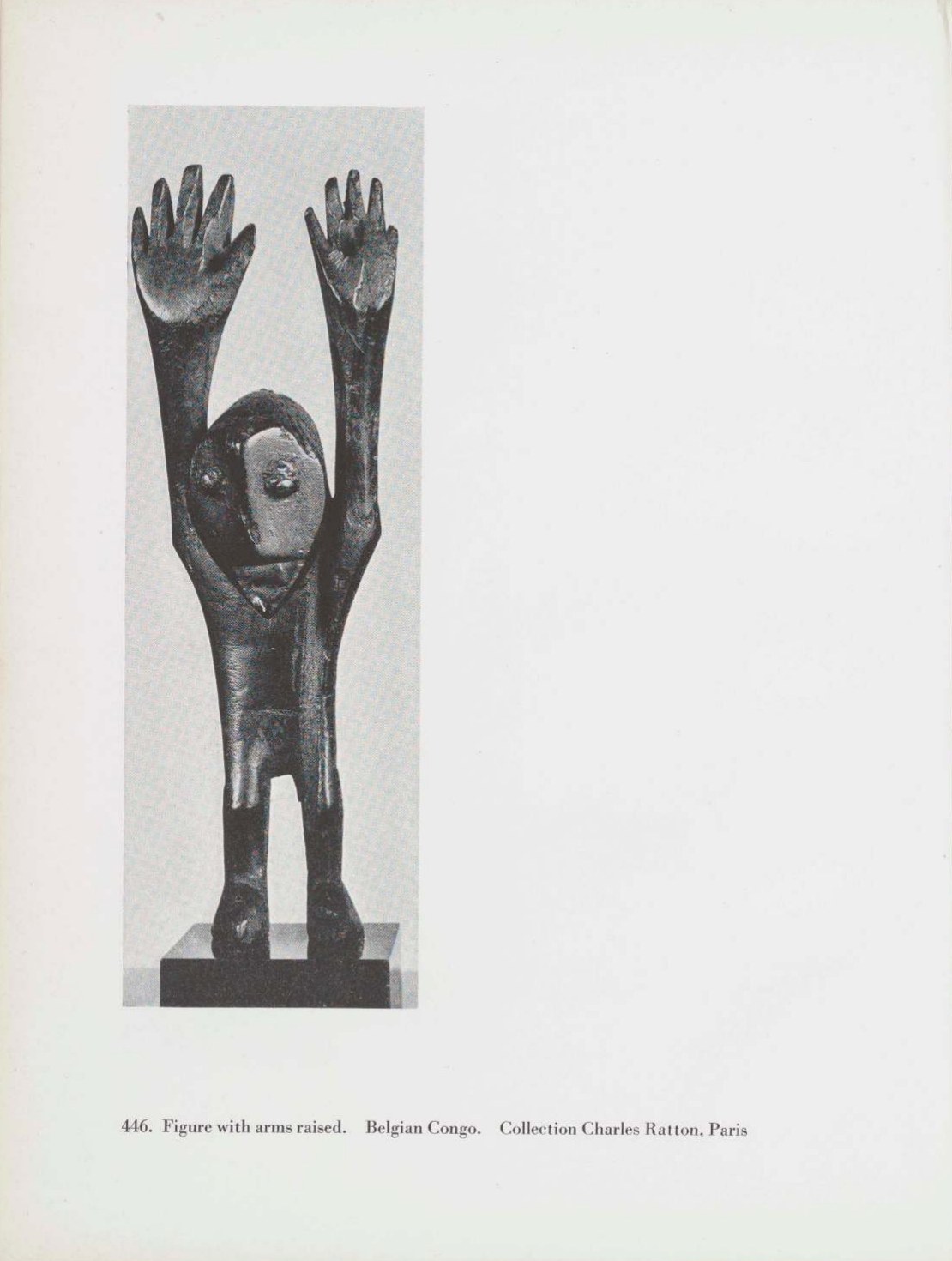

Religion with the Negro, as with all other races, has been the main stimulus to artistic expression. And even in minor manifestations we find it as productive in Africa as in Europe. For example, some of the finest expressions take the form of fertility idols such as No. 5 from the Sudan, or No. 403 from French Congo, or No. 443 from Belgian Congo; fetishes for conjuration such as No. 489; the well-known "Konde" nail studded figures (No. 436) used for driving away illnesses by hammering a nail into the figure at the moment of conjuration; representations of the spirit of the dead and figures to insure successful childbirth as well as protect the child till the age of puberty.

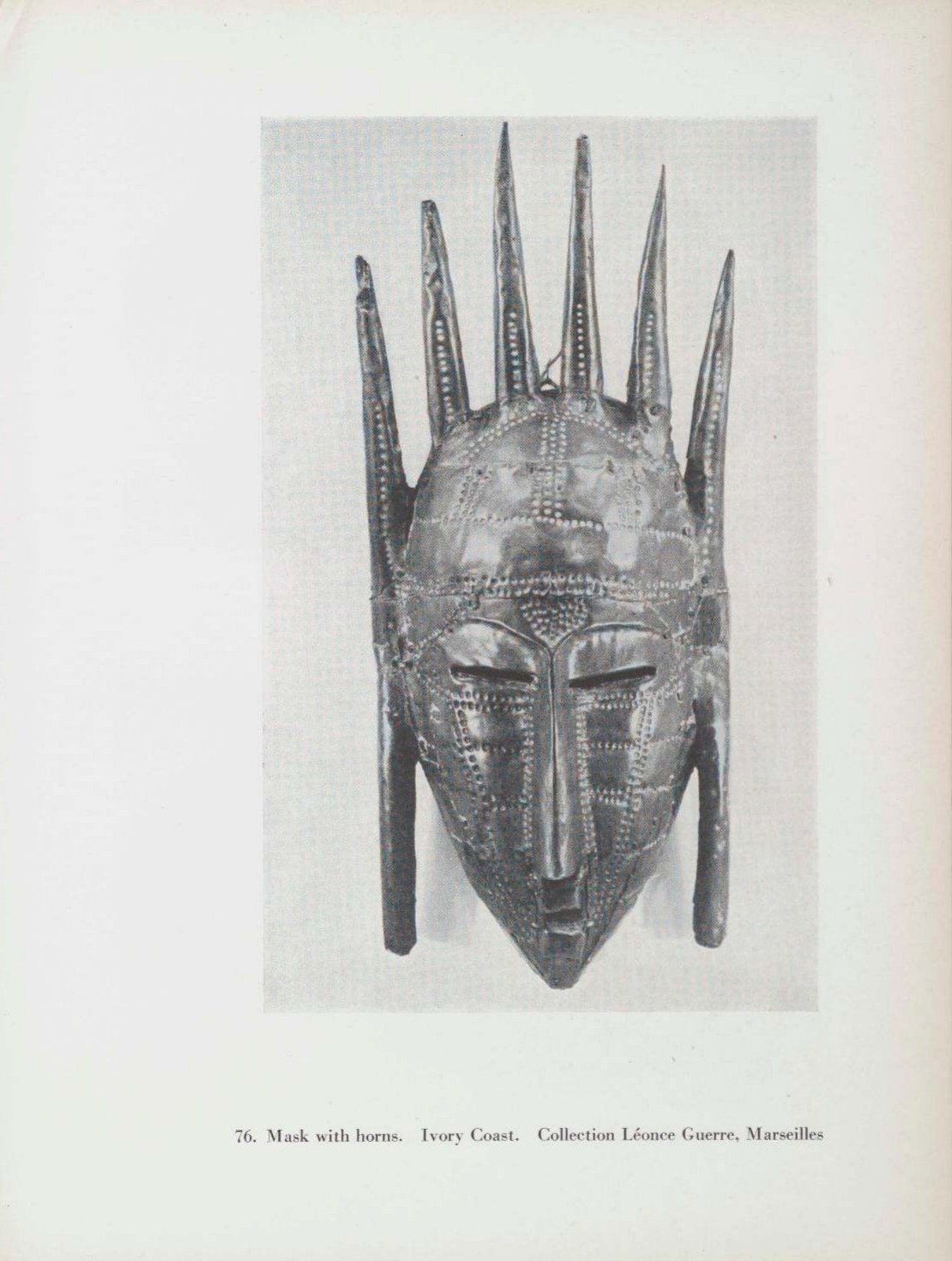

Certainly the broadest variety of expression, if not the highest, in Negro art lies in the field of ritual masks. They range from the most realistic, employing monkey or even human hair to heighten the representation (No. 52), to the most purely architectonic (No. 79) or abstract in form (No. 458); in size from the immense casques of the BaLuba fetish-men, or the "Kifwebe" fetish-man’s mask of the same tribe, to the small masks worn by women and children at secret society ceremonies or initiation rituals (No. 388). Some that are to be handed down within the tribe from fetish-man to fetish-man are meticulously carved; others to be worn at one circumcision ceremony, then to be thrown away, may be contrived crudely out of soft wood and painted with gaudy colours in some traditional pattern. And the purposes of the masks are as numerous as their varieties: fetish-men’s war masks, hunting masks, circumcision ritual masks; masks worn at funeral and memorial ceremonies—different variations of type in every tribe for every purpose—in wood, wicker, cloth, straw, parchment, ivory and endless combinations of materials.

Still African Negro art is by no means restricted to ritual objects. In practically every accessory of life, even the commonest utensil, the Negro’s sensibility and craftsmanship is illustrated: spoons (Nos. 177, 504), bobbins (Nos, 135, 139), headrests (Nos. 468, 472), musical instruments (Nos. 170, 338), even to the form of their bellows as we have it in No. 48. In the Belgian Congo, particularly among the Bushongo along the Kasai, we find textiles woven of cocopalm fibre in elaborate patterns. Even tattooing among the Negroes is art itself. To such an extent that the patterns which we find on the bodies of the natives are often the basis of those with which they decorate their sculptures and permit us in many cases to assign them to styles of specific tribes. And on the northern shore of the Gulf of Guinea, especially on the Gold and Ivory Coasts, we find a curious expression of lyric fantasy in small bronzes produced by the "cire perdue" method (Nos. 180-231) used by the natives for weighing gold-dust, frequently as remarkable in their technical mastery as they are individual in their imaginative conceptions.

Although the materials employed are usually dictated by circumstances of environment and expediency, immediate availability is not always a controlling factor. This we see illustrated by one of the main arguments in favor of the theory of Egyptian rather than Portuguese influence in the Benin bronzes. For while tin is ready to hand in Southern Nigeria, it has been found that the copper employed by the Binis in their earliest work was brought down from Egypt. In most cases, however, we find carving done in wood because of the facility in working it. When stone is used, it is almost universally a steatite or a soapstone. Gold wrork is practically limited to those regions where the mineral is found in the surface soil or in streams. The finest matting and tufted textiles are produced from the fibre of the cocopalm in the Congo region. However, ivory is widely employed from the Ivory Coast as far east as Tanganyika.

Because of the frequent migrations of tribes from region to region and tribal intermingling, it is difficult to attribute stylistic traits with any confidence to a people or an area. Also, our knowledge of Africa is still so slight that names are frequently as misleading as they are helpful. In an attempt to simplify the classifications of types, names have been applied with very little serious scientific basis. And modem political boundaries dictated by Europeans mean little to influences which have been spreading among the natives for generations. As an example, we find masks of the type commonly described as Dan and associated with the Ivory Coast, in west central Liberia (No. 53) and the characteristics which we might be tempted to associate strictly with Gabun are frequently to be found in Spanish Guinea and Cameroon (No. 322).

Certain features, however, may stand out. For example the definite character of surface decoration in BaKuba cups and boxes (Nos. 493-496) offers a ready contrast to the simpler more architectonic, though somewhat more naturalistic, sculpture of the BaLuba tribe which like the BaKuba is also of the Belgian Congo region. Again in the work from Gabun, both masks and figures, we find a suavity of harmonious relationships in the rounded surfaces and a swelling bulbous character in the volumes (Nos. 350, 356) that contrast distinctly with the severe staccato counterpoint of a statuette (Nos. 1, 13) or a mask (No. 21) from Sudan. Or the surface decoration of even the most ornate Ivory Coast mask (No. 116) may be simply distinguished by the emphasis it lays on relationships among its unit masses from the strictly linear patterns of the BaKuba style.

In the end, however, it is not the tribal characteristics of Negro art nor its strangeness that are interesting. It is its plastic qualities. Picturesque or exotic features as well as historical and ethnographic considerations have a tendency to blind us to its true worth. This was realized at once by its earliest amateurs. Today with the advances we have made during the last thirty years in our knowledge of Africa it has become an even graver danger. Our approach must be held conscientiously in quite another direction. It is the vitality of the forms of Negro art, that should speak to us, the simplification without impoverishment, the unerring emphasis on the essential, the consistent, three-dimensional organization of structural planes in architectonic sequences, the uncompromising truth to material with a seemingly intuitive adaptation of it, and the tension achieved between the idea or emotion to be expressed through representation and the abstract principles of sculpture.

The art of Negro Africa is a sculptor’s art. As a sculptural tradition in the last century it has had no rival. It is as sculpture we should approach it.

JAMES JOHNSON SWEENEY.

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements..7

The Art of Negro Africa by James Johnson Siveeney ..11

Previous Exhibitions of African Art...22

Museums Containing Collections of African Art..23

Bibliography .. 25

Catalog.30

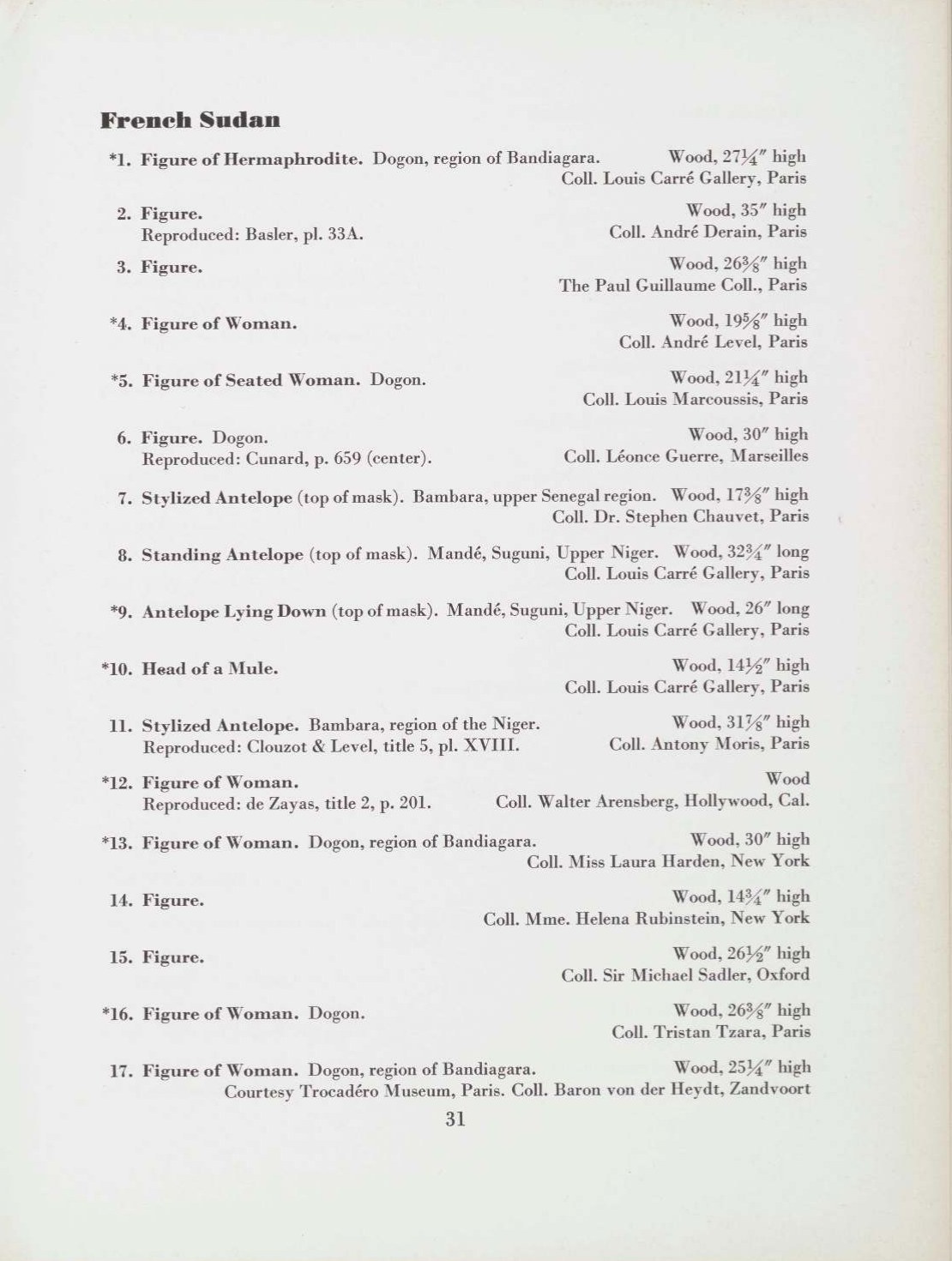

French Sudan ...31

French Guinea..33

Upper Yolta .33

Sierra Leone .33

Liberia. 34

Ivory Coast and Gold Coast..34

Dahomey...40

British Nigeria.41

Cameroon .44

Gabun..46

French Congo.48

Belgian Congo...50

Angola.58

British East Africa...58

Plates .59

Maps ...Inside back cover

Sample pages

Download link (pdf, yandexdisk; 23,0 MB).

Source: moma.org

18 мая 2018, 20:11

0 комментариев

|

Партнёры

|

Комментарии

Добавить комментарий