|

|

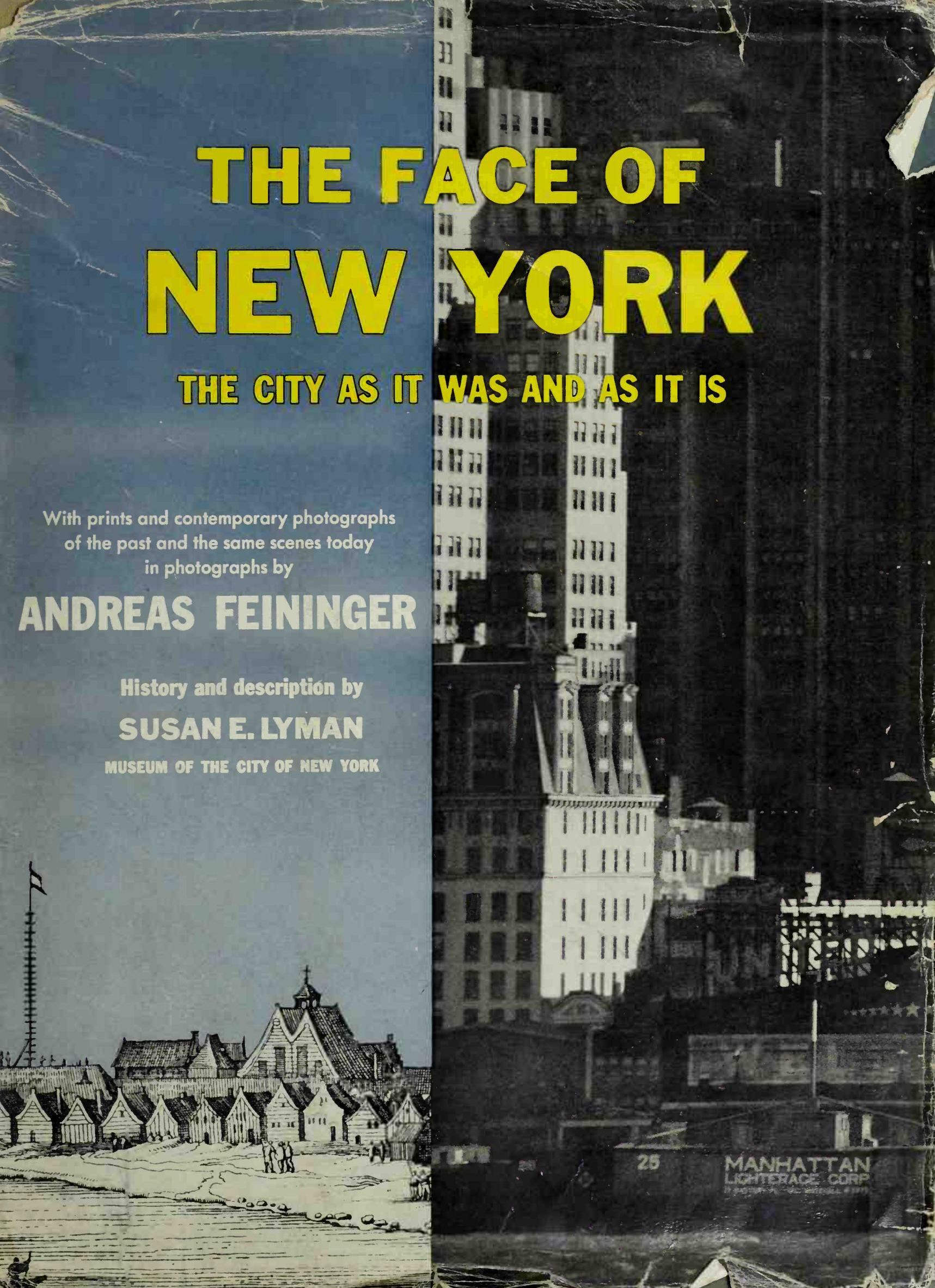

Andreas Feininger, Susan E. Lyman. The face of New York : The city as it was and as it is. — New York, 1954  The face of New York : The city as it was and as it is : With prints and contemporary photographs of the past and the same scenes today in photographs by Andreas Feininger : History and description by Susan E. Lyman, Museum of the city of New York. — New York : Crown Publishers, Inc., 1954. — XIV, 161 p., ill.

For lovers of magnificent photography as well as New Yorkophiles there can be no finer possession than this de luxe volume.

From thousands of prints, drawings and photographs in public and private collections, Andreas Feininger has selected the most colorful and picturesque views of old New York from the early Seventeenth to the early Twentieth Centuries. He then went to the very same places and photographed them as they are today.

Each two-page spread in the book contains one of Feininger’s superb photographs (with full technical data) of present-day New York, together with an earlier view or views of the same scene. The result is an amazing study in contrasts that will fascinate antiquarians and Feininger fans alike.

Susan E. Lyman of the Museum of the City of New York has written illuminating commentary for all of the pictures, pointing out historical spots of interest and important landmarks that still remain. Together with the introduction, this text is virtually a history of the changing face of New York.

AUTHOR’S FOREWORDThe Text

New York City is big in every way: masses of buildings, multitudes of people, and an incredible amount of activity. Things here are counted not singly, but by hundreds and thousands. This bigness which might well, by its ponderousness, have a stifling effect on anything as small as the individual living here has, instead, the opposite effect. It produces vehement feeling. How often do you hear the remarks, “I wouldn’t live in New York if you gave it to me,” and conversely, “I wouldn’t live anywhere else.” How rarely you hear a middle-of-the-road, unemotional comment. Everyone has convictions about New York.

Here, then, is the New York of Andreas Feininger, the convictions of a great photographer. For years he has explored the city, searching with his camera for the facets that to him mean New York and, through the medium of his extraordinary photography, capturing these to produce the face of his New York.

First of all, there are the skyscrapers, which for him have a savage quality, a reversion to the prehistoric that is unique among cities. Paradoxically, as the buildings have become giants, so the people have become infinitesimal, completely dominated, he feels, by the structures they have created. Yet the people themselves interest him strongly and he wanders among them, thinking of the many countries they came from, looking at their home surroundings and their daily activities. A part of the city for which he has a particular fondness is the waterfront, with its infinite variety of activity—and he watches the crowds pouring from a ferry boat, the heaving crane swinging a locomotive high into the air, and a superliner gently nosing into her berth.

Having established his modern New York, Mr. Feininger then turned to the past, to see what influences had shaped his city, what physical changes such as buildings and parks had affected certain streets and areas. At the Museum of the City of New York he found the answer in many different forms, perhaps captured by Eliza Greatorex’s romantic pen or Jacob Riis’s crusading camera; maybe a scene engraved by an unknown artist two centuries ago or a detail photographed by Percy Byron in 1900.

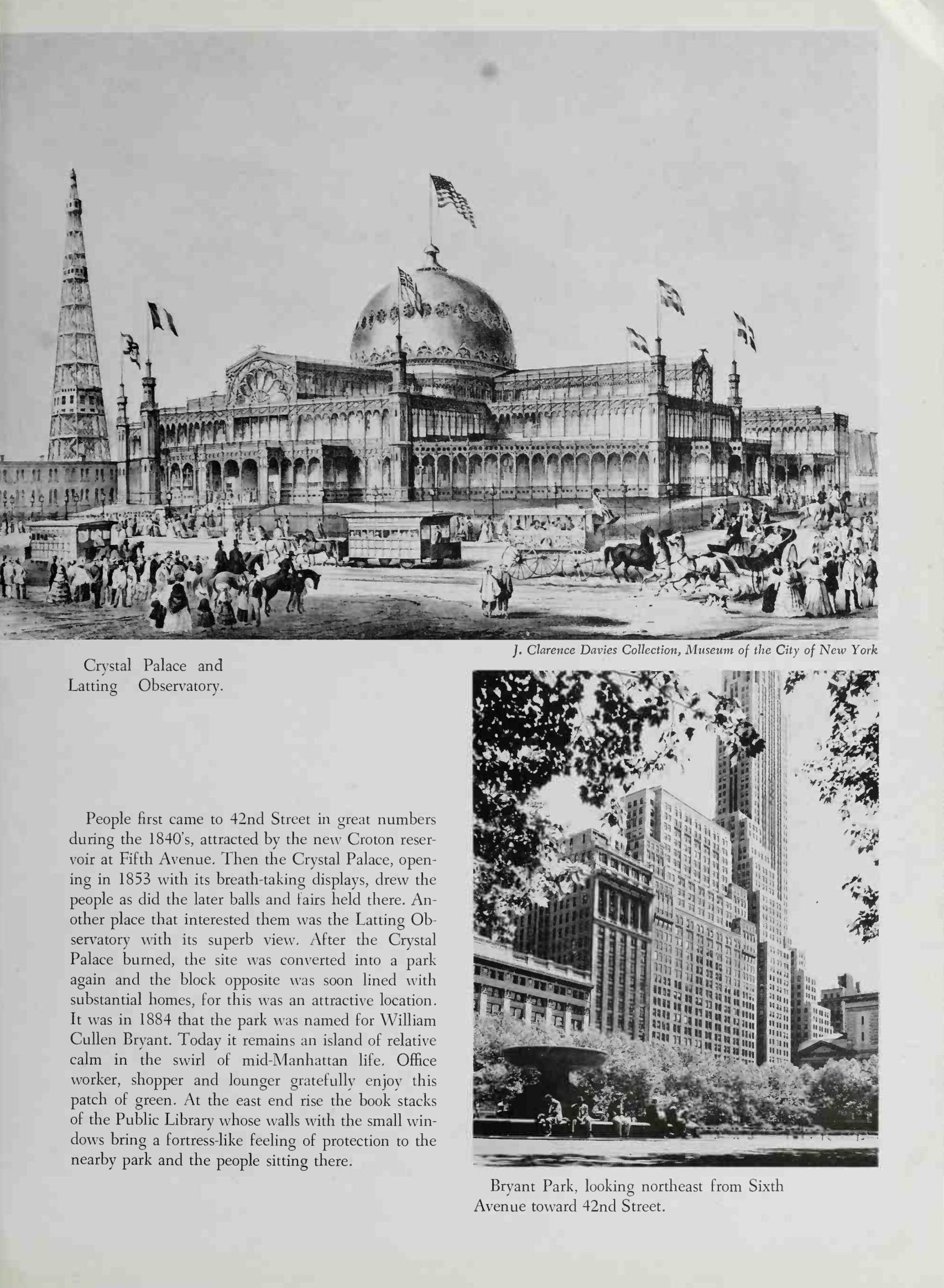

By this time I was working along with Mr. Feininger, trying to bring 350 years of New York history into focus with this picture of the present city. After a final choice of material was made, to me fell the pleasant task of attempting to tell the history behind each picture, to tie in the unfamiliar past with the well-known present. All of us are aware of bits and pieces of city history. Yes, we know it was once a Dutch town, but we aren’t sure how much area it covered then. We’ve read of the Crystal Palace but have no idea where it stood. Maybe we’ve been lucky enough to hear an old-timer describe the building of Brooklyn Bridge or the rigors of an immigrant’s arrival at Castle Garden—but we’ve not seen pictures of these events. Here, in this book, you’ll be able to fit together some of these pieces of history. You’ll be able to link the old and the new—a very satisfying thing to do because history is that third dimension which brings depth to any scene of the present.

Finally, looking ahead to the next time that you ramble through the city, I hope that you will recollect some of the pictures you’ve looked at in this book. For instance, the next time you stop by Rockefeller Center, may you see not only the ice-skaters on the Lower Plaza but also the visitors to Dr. Hosack’s Elgin Botanic Garden. As you walk along 42nd past the towering Chrysler and Daily News Buildings, may you see also the cluster of shanties that stood there in the 1860’s. And, best of all, as you fly over the city, may you see not only the skyscrapers and the pattern of streets, but also the open green countryside of Manhattan Island with the small Dutch village at the tip, for this is all part and parcel of our New York.

Susan Elizabeth Lyman

AUTHOR’S FOREWORDThe Pictures

In compiling the material for this book, the most important considerations were those of selection and presentation—what to show, and how to show it.

To assemble a complete pictorial record of a city the size of New York is physically impossible. In addition to its prohibitive size and cost, any such volume would also be rather boring, since so many aspects of a city, no matter how important to its proper functioning, are so familiar to the average reader that he has no desire to see them reproduced in the form of photographs.

Furthermore, the appearance of public buildings such as railroad stations, post offices, court houses, theatres, museums, libraries, etc., is so standardized throughout the world that they look more or less the same, whether they are located in New York, London, Cape Town, or Hongkong. No matter how indispensable to the civic and cultural life of a city, such buildings are not typical of New York, and consequently, photographs of such stereotyped subjects have been deliberately omitted in favor of more significant views.

More than most other cities, New York abounds with interesting features because it possesses three distinct qualities: located at the junction of an ocean and a continent, it is the world’s biggest city; it is built on an island; and it has the longest waterfront of any city on earth.

The repercussions of this are threefold:

New York’s immense size attracts from all points of the globe initiative, talent, and wealth which, directly or indirectly, have created such spectacular achievements as Rockefeller Center, the Empire State and United Nations Buildings, Wall Street, Fifth Avenue, and other equally exciting features.

Because its island location limited New York’s horizontal expansion, the city was forced to grow upward. This fact was primarily responsible for the evolvement of that typical American symbol, the skyscraper, which has nowhere attained such spectacular dimensions as in New York, culminating in the famous skyline.

And finally, thanks to its 770 miles of sheltered waterfront, New York possesses not only the largest, but also one of the finest harbors on earth. As a result, New York has direct sea-connection with some thirty foreign countries and access to commerce with the entire world.

My main consideration in assembling the illustrations for this book was to do justice to these and other aspects of the city which unmistakably spell “New York.”

However, no matter how carefully selected and how typical of New York, unless presented in a photographically effective form, even the most interesting subjects become meaningless and dull.

For example, seen from almost anywhere along Fifth Avenue (where it is located), the Empire State Building, the tallest structure in the world, for reasons of perspective appears lower than most of the actually much smaller skyscrapers that happen to be closer to the observer. No photograph taken from any such viewpoint, of course, gives a true impression of this spectacular building, which can only be fully appreciated when seen from a distance. Similarly, only when seen from an adequate distance does New York’s magnificent skyline appear at its monumental best. The closer the viewpoint, the more do relatively low but nearby buildings hide the taller but more distant structures that line the backbone of Manhattan, the less does one see of the skyline, and the less interesting do the photographs appear. To counteract these deceptive effects of “perspective,” the author, whenever possible, took his pictures from a distance with the aid of a telephoto lens.

In this connection, it seems necessary to point out that, contrary to often-encountered opinion, telephoto lenses do not produce pictures in which perspective is “distorted.” Such photographs may appear unusual and surprising, but as far as perspective is concerned, they are no more “distorted” than pictures taken with ordinary lenses. This can be verified easily: take a number of photographs of the same subject from the same camera point of view, but with lenses of different focal length (wide-angle, standard, or telephoto). If enlarged to the same scale, the photographs may differ in sharpness and definition as a result of their different degrees of enlargement, but they are identical as far as perspective is concerned. The area encompassed by the lens, of course, may vary, but within this area, line for line and angle for angle, perspective will be found to be the same, and the pictures will register perfectly if superimposed one upon the other.

Telephotographs render in picture form a view as it would appear to the eye if seen through a pair of binoculars. They depict only a comparatively narrow angle of a scene, but render this section in a scale large enough to show detail that from the camera point of view cannot be distinguished by the eye because it is too far away. Since they show the subject in a form which differs from that in which we saw it when we took the picture, telephotographs may seem unusual. However, this quality, far from being a type of “distortion,” actually represents a form of intensified seeing. Used in this sense—as a means for extending our visual experience—the telephoto lens helps us to see more clearly subjects as they truly are, freed from the misleading chance-effects of “perspective.” As mentioned before, photographed from close by with an ordinary lens, the Empire State Building appears less tall than buildings which are actually lower but nearer. This apparent smallness, which is caused by perspective and which is contrary to fact, is in effect a form of distortion. On the other hand, in telephotographs taken from farther away, the Empire State Building rises monumentally above its lower neighbors. Because telephotographs come closer than pictures taken with an ordinary lens to preserving the true proportions of the subject, they create impressions which conform more closely to reality. This makes telephotographs the more effective type of picture.

For similar reasons, the author, as far as possible, utilized other typically photographic qualities in order to depict effectively his vast subject, New York. To mention one more example: in black-and-white photography, color, of course, cannot be rendered directly (as in a color photograph), but must be represented in the form of different shades of gray. Because of the various controls which a photographer has over his medium, this can be done in several ways. The common approach to the problem of color translation into terms of black and white is to match brightness of color and gray shade. But such a “literal” approach has one serious disadvantage: in reality, colors of equal brightness appear separated because of differences in hue; transformed into corresponding shades of gray, however, colors different in hue but equal in brightness appear as identical gray tones; differentiation is absent, and objects merge one into another. To avoid this, the author, with the aid of color filters, transformed color values into degrees of contrast, and “symbolized” the color effect of his subjects by means of stark and “graphic” black and white.

All the New York City photographs taken by the author were made on Kodak Super XX Film; exposed in accordance with readings taken from a Weston exposure meter; processed in Kodak Developer D-76; and enlarged on glossy Kodabromide Paper developed in Kodak Developer D-72. Three different cameras were used: for the close-ups, a twin-lens reflex camera 214″ x 214″; for the medium-long shots, a single-lens reflex camera of the same size in conjunction with telephoto lenses of different focal lengths; and for the long shots, a specially constructed 4″ × 5″ view-type camera and lenses with focal lengths up to 43″.

The author also made all the reproductions of historical photographs, lithographs, and engravings used in this book. While engaged in this work, he was struck by the excellent state of preservation of the engravings—many of them two and three hundred years old—as compared to the poor condition of photographs taken only fifty to seventy-five years ago. While the paper of the engravings still appeared white and crisp, and the lines sharp and black, most of the photographs were already faded, yellow, and seemed destined to complete obliteration within a relatively short time—eloquent testimony to the impermanence of our present methods of graphic representation. The reproductions of the old photographs in this book appear relatively contrasty only because of modern techniques of copying which, to a certain extent, permit restoration of the contrast of the faded original.

Another fact which greatly impressed the author was the high degree of skill and the attention to detail with which most of the old engravings and lithographs were executed. As a result, small sections of old prints could be photographed and enlarged without noticeable loss of detail. Several unusual and significant pictures were produced in this manner.

All copy-work was done on Kodak Plus-X Film 4″ × 5″, developed in Kodak Developer D-76, and, in accordance with the requirements of the reproduction, printed on Kodabromide Paper of medium or hard gradation.

Andreas Feininger

Sample pages

Download link (pdf, yandexdisk; 51,3 MB).

Все авторские права на данный материал сохраняются за правообладателем. Электронная версия публикуется исключительно для использования в информационных, научных, учебных или культурных целях. Любое коммерческое использование запрещено. В случае возникновения вопросов в сфере авторских прав пишите по адресу 42@tehne.com.

20 января 2021, 1:31

0 комментариев

|

Партнёры

|

Комментарии

Добавить комментарий