|

|

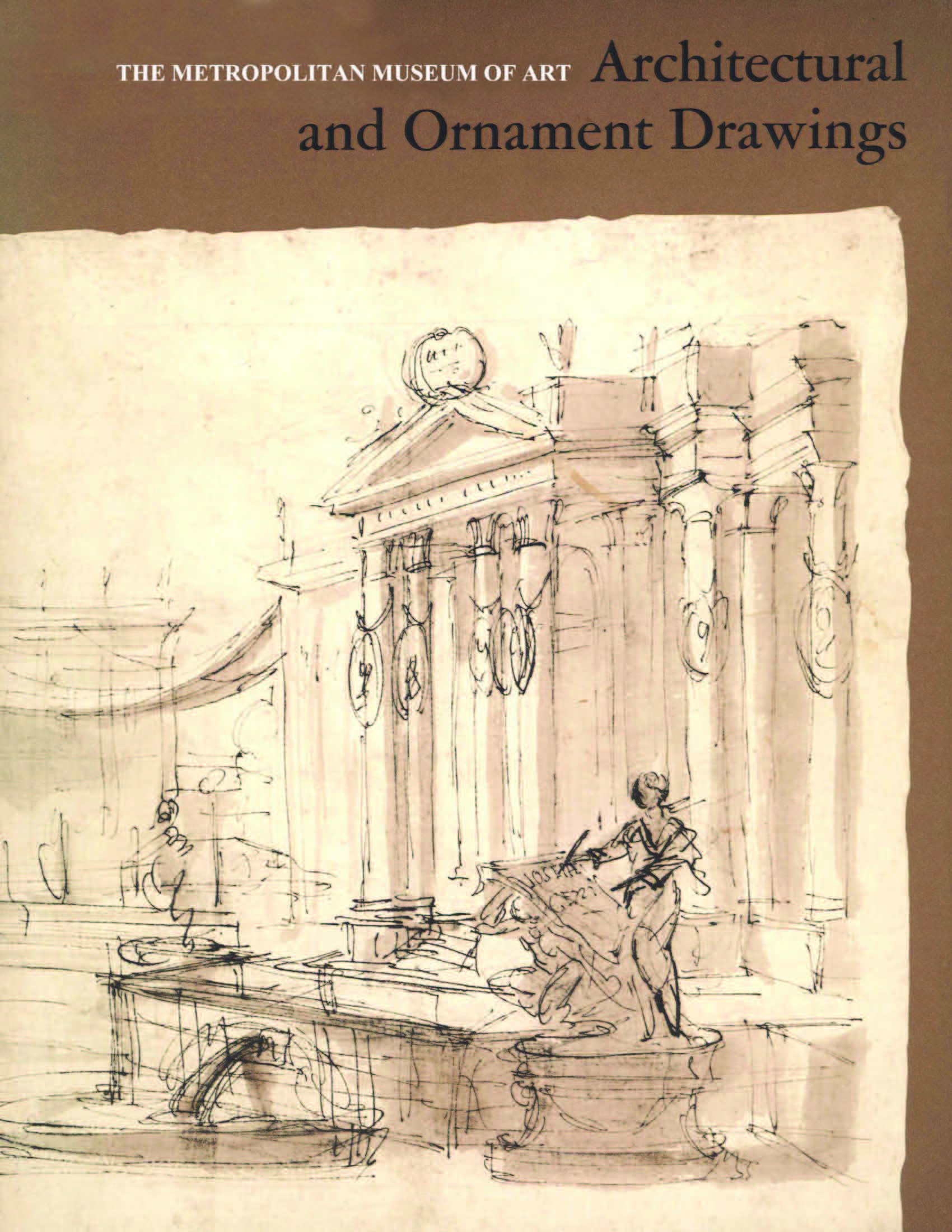

Architectural and Ornament Drawings: Juvarra, Vanvitelli, the Bibiena Family, and Other Italian Draughtsmen : Catalogue by Mary L. Myers. — New York, 1975  Architectural and Ornament Drawings: Juvarra, Vanvitelli, the Bibiena Family, and Other Italian Draughtsmen : Catalogue by Mary L. Myers. — New York : The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1975. —56 p., 88 p. of ill. — ISBN 0-87099-126-4Foreword

From about 1900 to 1960 American museums collected at the fastest rate and with the widest interests that the world has ever seen. This sweepstake ingurgitation has now pumped the sources dry and has sent prices skyrocketing for what remains, just at a time when American museum funds are falling behind the rate of general inflation. But the result is not entirely disastrous, for it forces us to take stock of what we raked together bit by bit as chances offered, and to catalogue the holdings that have grown almost without our being aware of the growth. While a few excellent catalogues have been published, mostly by the Morgan Library, the Frick Collection, and this Museum, American collections are still so little known that we ourselves in the museums are unaware of treasures in nearby museums, and are sometimes unaware of remarkable things in other departments of our very own buildings. It would be useful if all American museums would pool their resources for countrywide surveys of some scarcer specialities like, say, German drawings, Islamic glass, Greek jewelry, or Romanesque sculpture.

In this catalogue Mary L. Myers publishes a selection of the Metropolitan Museum’s drawings for stage sets, furniture, silver, architecture, and many other forms of applied art. To show these practical drawings in use, she has selected many that are projects for known works of art. Yet however utilitarian in intention, these drawings often achieve the perfection that is sometimes attainable in the decorative arts, but never in the more complex overtones of the expressive arts.

A. Hyatt Mayor

Curator Emeritus, Prints

Introduction

It is often a surprise to visitors to the Museum’s Print Study Room that we possess, as a complement to our collection of architectural and ornament prints and books, a large collection of architectural and ornament drawings. William M. Ivins, Jr., the first curator of the Department of Prints, founded in 1917, set about building a comprehensive collection of printed architecture and ornament as a natural addition to our collection of engravings, etchings, and lithographs. His essays on the ornament collection and on the many exhibitions of ornament he arranged show that he felt that an engraving of a metalwork design by a master silversmith was as telling for its period as a fresco or etching.

It may be useful to explain here why two of the Museum’s departments contain drawings: the Department of Drawings and the Department of Prints and Photographs. The Department of Drawings was created only in i960. Before that time figure drawings were not acquired in the systematic fashion that their specialized department acquires them now; instead, they were collected by the Curator of European Paintings as significant works came to his attention. Through the forty-three years preceding the founding of the Department of Drawings, ornament prints and drawings were added to the collection in the Print Room. By 1960 that collection was an impressive one, and the maintenance of its unity seemed in the long run more useful than breaking it up and adding architectural and ornament drawings to the figure drawings in the Drawings Department.

The first major purchase of architectural and ornament drawings was in 1934, when William Ivins bought a large scrapbook of English drawings containing designs by Robert and James Adam, William Chambers, James Wyatt, and Thomas Hardwick. When A. Hyatt Mayor became curator in 1946 he began to buy ornament drawings whenever he found them. In 1949, we received our first considerable group of Italian ornament drawings when we acquired part of Janos Scholz’s collection of drawings for ornament and book illustration. Although that lot contained several Italian eighteenth-century drawings, it was composed primarily of sixteenth-century drawings. In 1952, the bulk of Janos Scholz’s ornament drawings came to us, and within the lot was a series of eighteenth-century drawings that formed the nucleus of the collection that has expanded regularly since. Among the Scholz drawings were most of our Bolognese drawings, including those in the exhibition by Carlo Bianconi (Nos. 5-7), Flaminio Minozzi (Nos. 44a and b), and Mauro Tesi (Nos. 57, 58), as well as an extraordinary group of drawings by Giovanni Battista Foggini (Nos. 23, 24, 26), more extensive than any I know outside of Florence and Rome.

Within the last decade, our collection of eighteenth-century Italian drawings has grown into one of the important collections of its kind. In 1964, seven drawings after Luigi Vanvitelli’s theater at Caserta and the festivities he designed to honor the marriage of Ferdinando, king of Naples and Maria Carolina of Austria were purchased (Nos. 69-75). This acquisition inspired the generous gift of Donald Oenslager’s collection of five drawings by Van-vitelli (Nos. 62, 64-67). With the subsequent purchase of three others, the Museum’s collection of Vanvitelli drawings became the most comprehensive known outside those in Naples and Caserta. A large scrapbook of Piedmontese drawings comprising designs for church and palace interiors, altars, fountains, stage sets, and other decorations, was given to the Museum in 1965 by Leon Dalva (Nos. 30, 40-43, 81). These drawings give a broad and clear idea of design in that region that served as a fertile ground for ideas passing back and forth from Italy to France, Austria, and Germany. In 1969, John McKendry, who succeeded A. Hyatt Mayor as curator, purchased for the department a volume of drawings by Filippo Juvarra (No. 36). One of the five Juvarra albums outside of Italy, it is the only one in the United States. Two years later the purchase of a number of drawings from the collection of Sidney Kaufman of London added several important sheets by, among others, members of the Bibiena family, two of which are exhibited here (Nos. 9, 10), stage sets by Mauro Berti (No. 3), Serafino Brizzi (No. 19), Fabrizio and Bernardino Galliari (No. 31), a sheet by Vanvitelli (No. 68), and an interesting group of anonymous drawings (Nos. 80, 83, 84). Seventy-two formerly unknown drawings, most of them preparations for engravings of projects of different members of the Bibiena family, were purchased in 1972 (Nos. 11-17). Finally, as this catalogue was being written, we acquired, with the assistance of the Ian Woodner Family Foundation, a group of drawings by Giovanni Battista Natali, a draughtsman whose works have often been attributed to better-known artists, such as Ferdinando Bibiena (Nos. 48-51).

New York has rich collections of architectural and ornament material. Columbia University’s Avery Library is one of the world’s great architectural libraries. The combination of the collections of ornament and architectural drawings of the Metropolitan Museum’s Department of Prints and Photographs and that of the Department of Prints and Drawings at the Cooper-Hewitt Museum (formerly the Cooper Union Museum), as A. Hyatt Mayor has observed, now makes New York the place to study ornament, along with Berlin. The older, comprehensive collection of ornament in the Ornamentstichsammlung in the Kunstbibliothek there, despite its losses in World War II, remains the major European center for studying ornament.

The person who prepared the ground for the study of New York’s collections of ornament drawings was Rudolf Berliner. He catalogued the twelve thousand from the Piancastelli collection (see Lugt S 2078a and 1860c) acquired by the Cooper-Hewitt Museum. That was a herculean task to which he applied his profound knowledge of European decorative arts and drawings. He also made many visits to the Metropolitan Museum’s Print Room. I well remember in the early sixties a gentle, modest man who freely identified and discussed our drawings with Hyatt Mayor and Janet Byrne. He never wrote his observations on the mats as many scholars do—they appear always in the hand of one of our staff members—and as his time was always short, and he had much material to work through, the notes were brief and not attributed to him. I cannot emphasize enough, however, the enormous debt that this catalogue owes to him. He prepared the foundation for the study of our collection just as he had done with Cooper-Hewitt’s. My debt to Rudolf Berliner is, in fact, a dual one; I studied the collection at Cooper-Hewitt at every turn, and it was often a drawing there that he had catalogued that identified one of ours. His contributions were pervasive but nearly anonymous, and I have not always been able to give the specific credit due him in the individual entries.

The aim of this exhibition is to present as comprehensive a view of eighteenth-century Italian ornament and architectural draughtsmanship as our collection allows. One name is conspicuously absent—that of Giovanni Battista Piranesi, who designed the small church of S. Maria del Priorato on the Aventine hill in Rome and was charged with some work for the interior of the Lateran. However, Piranesi is well represented in other New York collections: the Pierpont Morgan Library possesses drawings for S. Maria del Priorato and the Avery Library, projects for the Lateran.

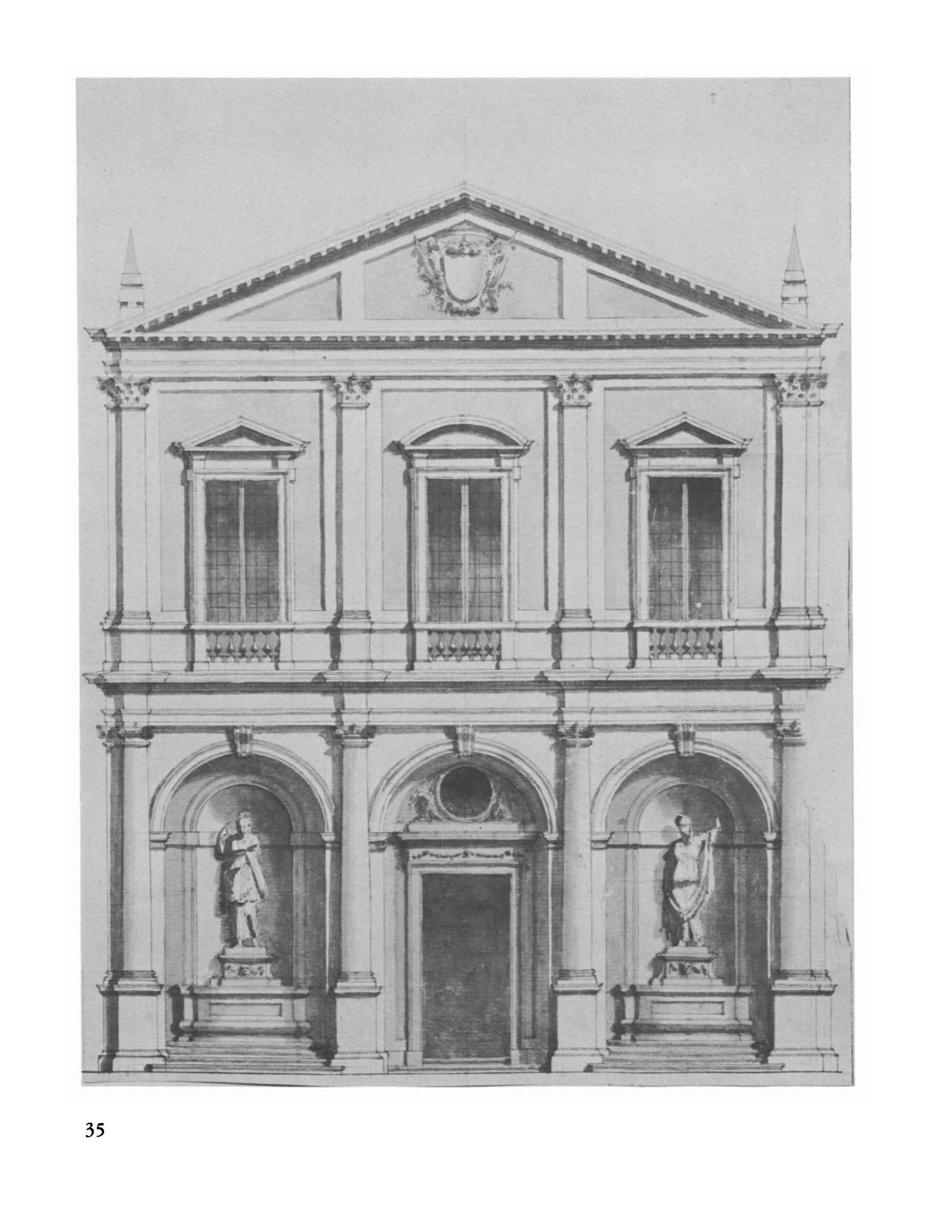

Although this exhibition focuses on the eighteenth century, the limits are not strict. The sheet by Juvarra’s master, Carlo Fontana (No. 29), the most influential and active architect in Rome at the beginning of the century, was included, although our drawing is an early one, dating to the 1660s. The situation is the same for the end of the century; although the projects in our drawings by Felice Giani (No. 33) are not precisely identified or dated, they may well have been made in the second decade of the nineteenth century. However, Giani’s neoclassic outlook was formed in the eighteenth century, and thus presents a fitting conclusion to the evolution of ornament styles shown in the exhibition.

The projects presented in this selection of drawings are diverse. Furniture design is represented by sketches for an armchair, a table, and a mirror frame. Metalwork is represented by designs for clocks, coffee urns, and ecclesiastical objects. There are even designs for calling cards.

There are designs for interior decoration: projects for ceiling and wall painting and stucco work, and even a sketch of a bed alcove. The painted walls and ceilings of Italian palaces during this period were often decorated with illusionistic perspective views in an architectural setting. This feigned, painted architecture is known as quadrature and its painter, a quadraturista. Pictures, often inserted into the quadratura as if distinctly framed, independent paintings, are called quadri riportati. They were often, in the eighteenth century, views, or vedute, but were sometimes figural. For example, the scenes of the Passion in Vincenzo dal Rè’s ceiling (No. 54), are quadri riportati in a quadratura background. Quadratura was also often combined with stucco so that sham architecture had, in fact, some three-dimensionality. Some of the curling foliage in the dal Rè ceiling, thus, may have been intended for execution in stucco.

Designers often prepared their inventions for the engraver. Many of our drawings of cartouches were probably meant to be engraved in pattern books as models for other craftsmen and students. Engravings were also made in honor of a prince or other patron; the Bibiena catafalque designs (Nos. 15-17) are drawings for prints to honor the deceased. Likewise, the engravings that were projected after the drawings for Francesco Bibiena’s Nancy theater (Nos. 11-12) would have glorified Leopold, duke of Lorraine, who had commissioned the theater.

Stage designs, which may be considered the Italian eighteenth century’s ultimate expression of architecture and ornament in combination, are presented in great number. Also represented is another aspect of eighteenth-century theater, the Theatra Sacra, designs for church celebrations, executed, for instance, for those held during Holy Week. Another form of temporary religious decoration represented here is for the celebration of the canonization of a saint (No. 38). There are also a number of catafalques, allied by virtue of their temporary nature to designs for fêtes and the stage.

A number of the drawings in this catalogue are described as having a Gothic A stamped in purple ink either on the drawing or on its mount. This Gothic A was described by Lugt (Lugt S 47a) as an unidentified mark on a collection of drawings which, he reported, may have belonged to the Savoia-Aosta family and was said to have been found in a family palace in Brianza, the region between Milan and Lake Como. Rudolf Berliner thought it strange, if not impossible, for a titled Italian family to employ a Gothic letter as its mark. The present duchess of Aosta recently wrote that she knew of no collection in her family that employed such a mark, and that the Aosta family has never owned a palace in Brianza. I therefore believe it impossible that the Gothic A refers to the Aosta family. For that reason, I do not list the Lugt number each time the mark appears, since it seemed cumbersome to correct the Lugt citation each time. It is likely that the Gothic A reflects an Austrian or German provenance for the drawings.

We are pleased to be able to present in this exhibition, the first the Metropolitan has ever devoted entirely to architectural and ornament drawings, a part of our collection that deserves to be much better known.

M. L. M.

October 1974

Sample pages

Download link (pdf, yandexdisk; 18,2 MB).

Все авторские права на данный материал сохраняются за правообладателем. Электронная версия публикуется исключительно для использования в информационных, научных, учебных или культурных целях. Любое коммерческое использование запрещено. В случае возникновения вопросов в сфере авторских прав пишите по адресу 42@tehne.com.

2 февраля 2020, 21:41

0 комментариев

|

Партнёры

|

Комментарии

Добавить комментарий