|

|

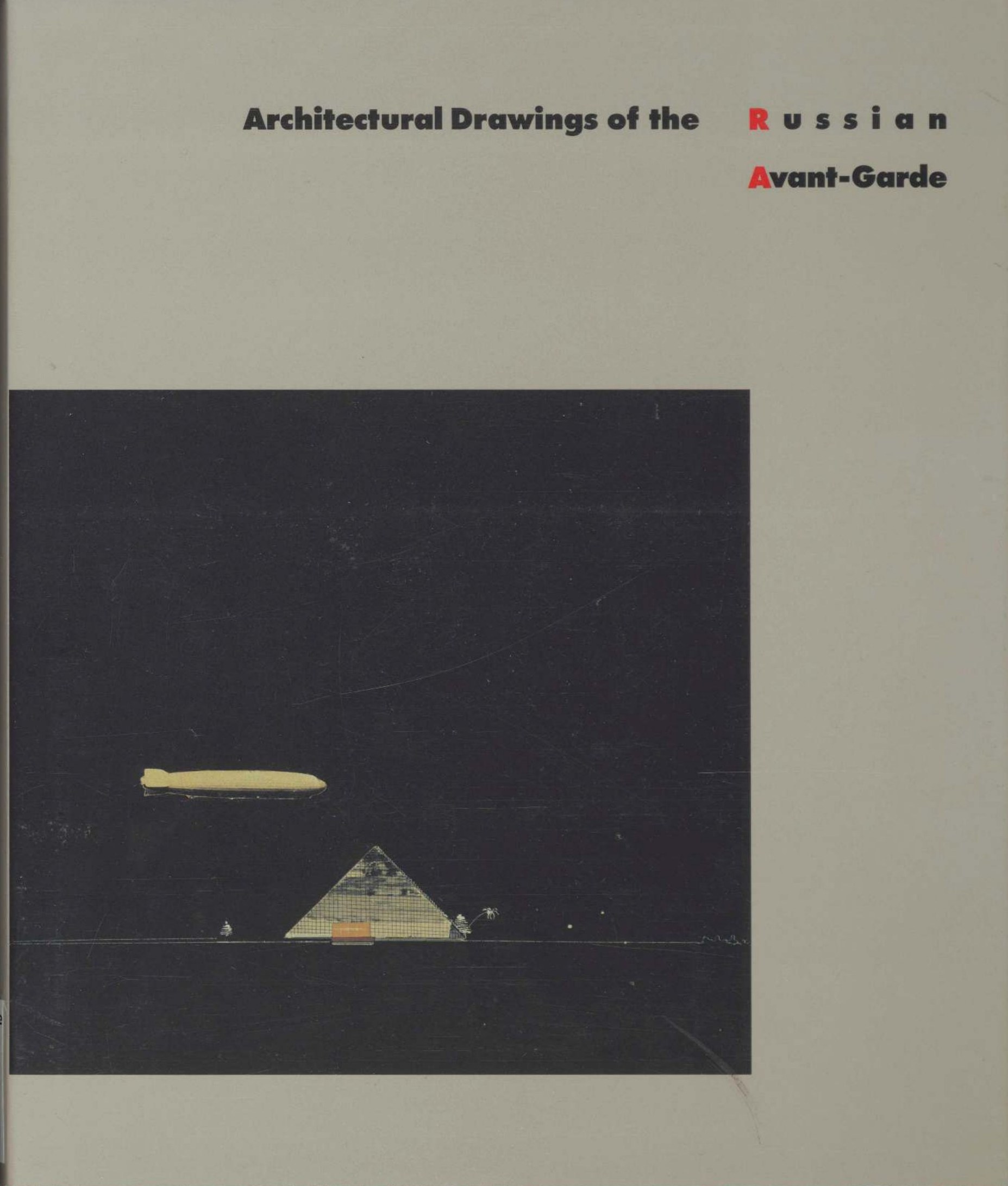

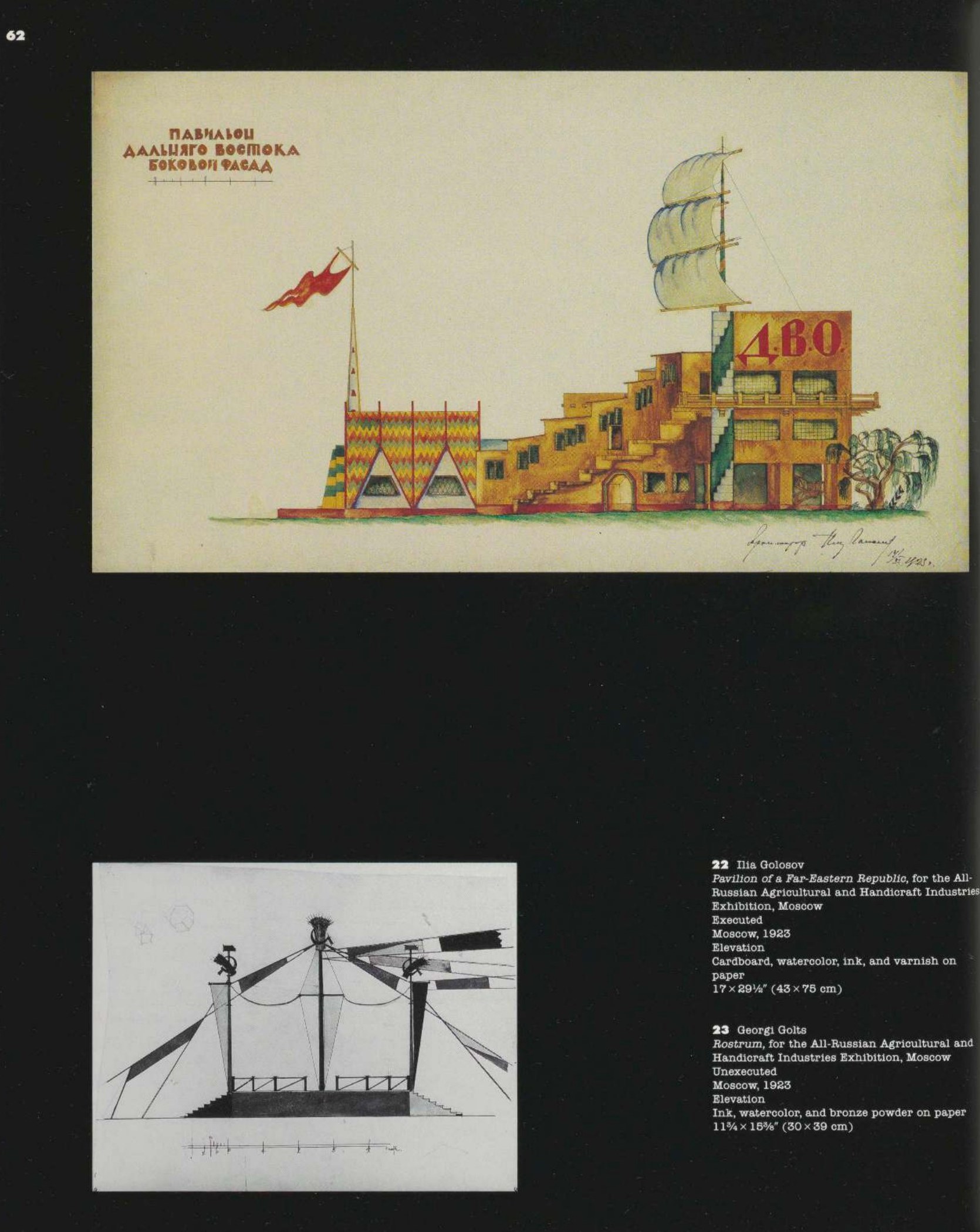

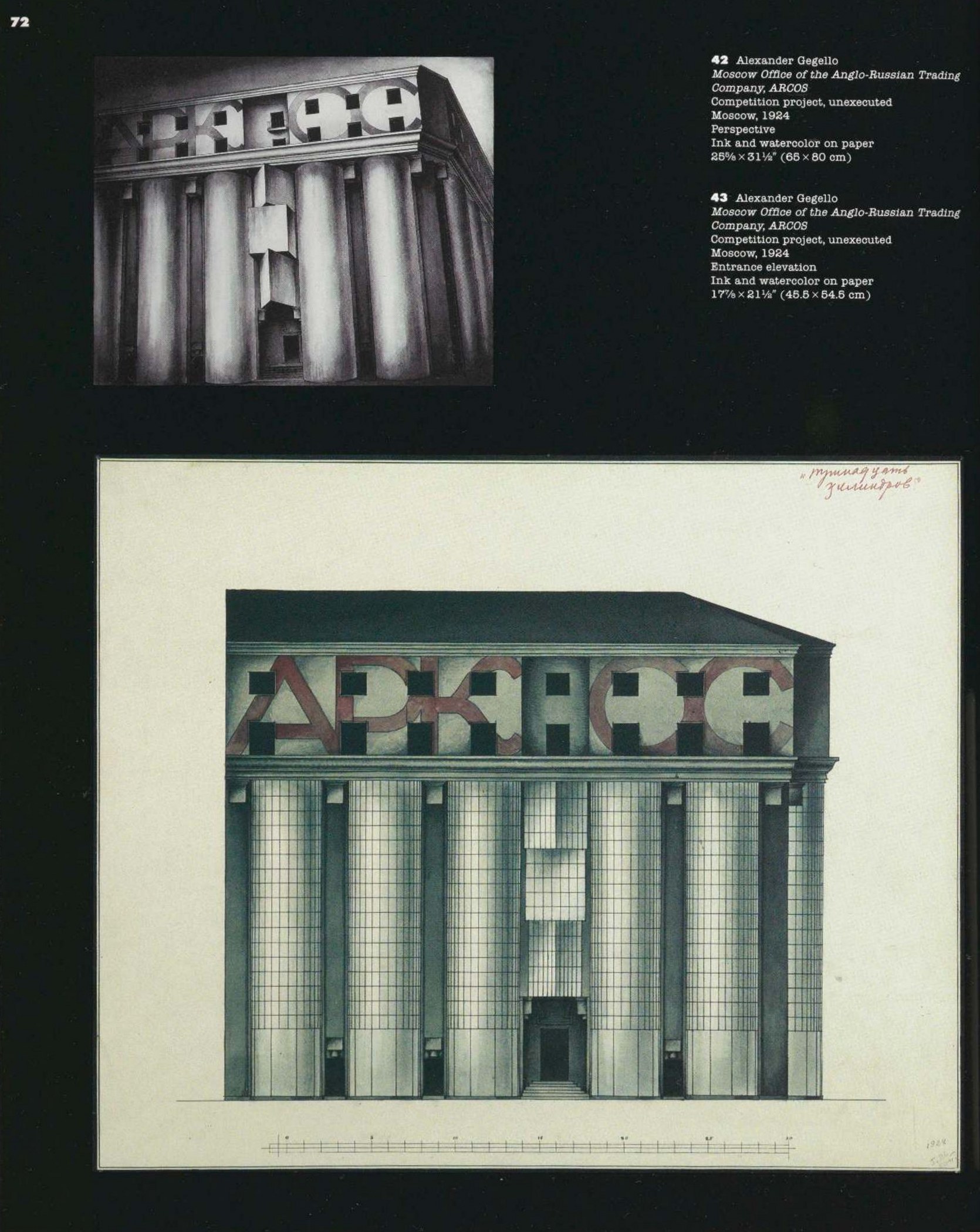

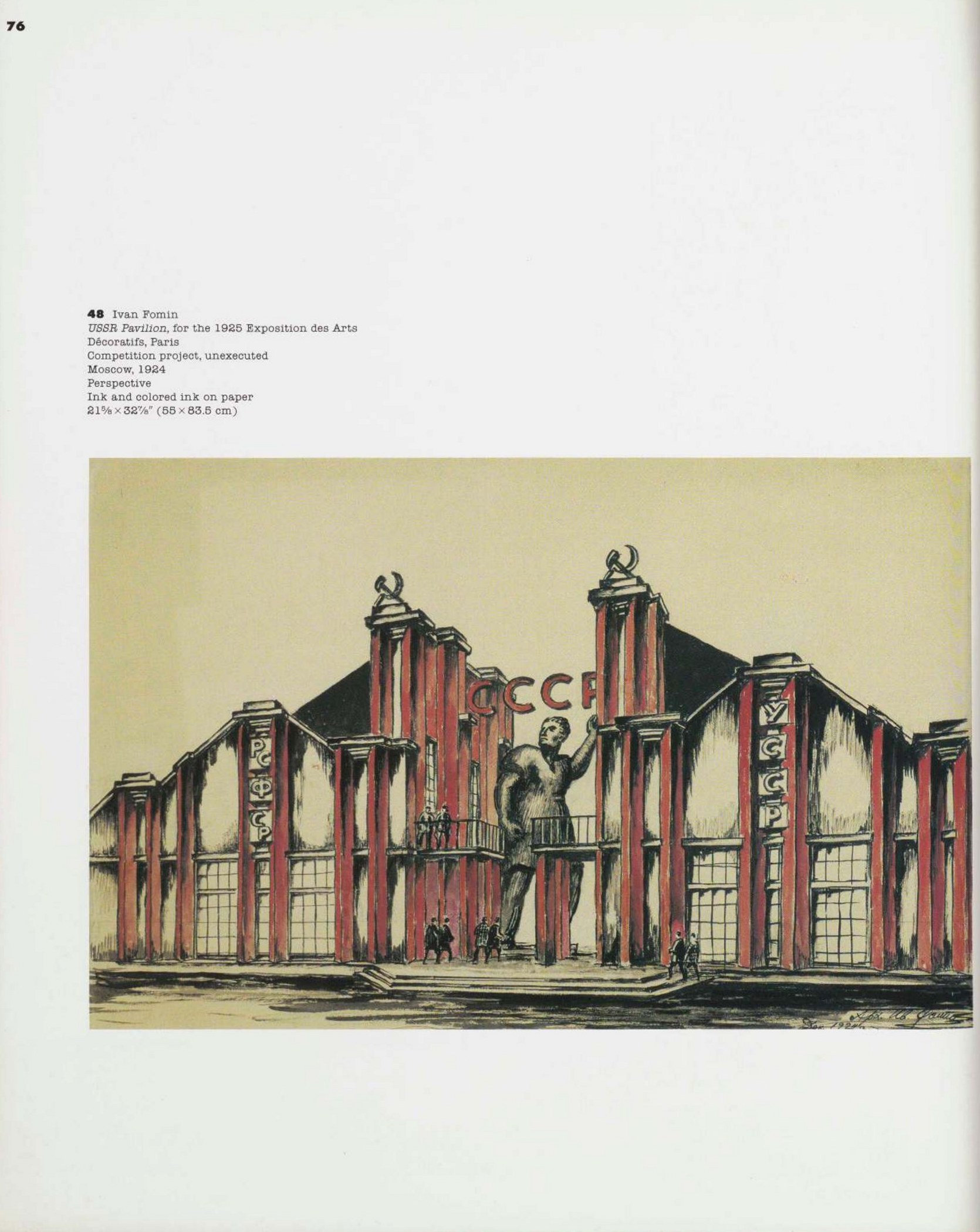

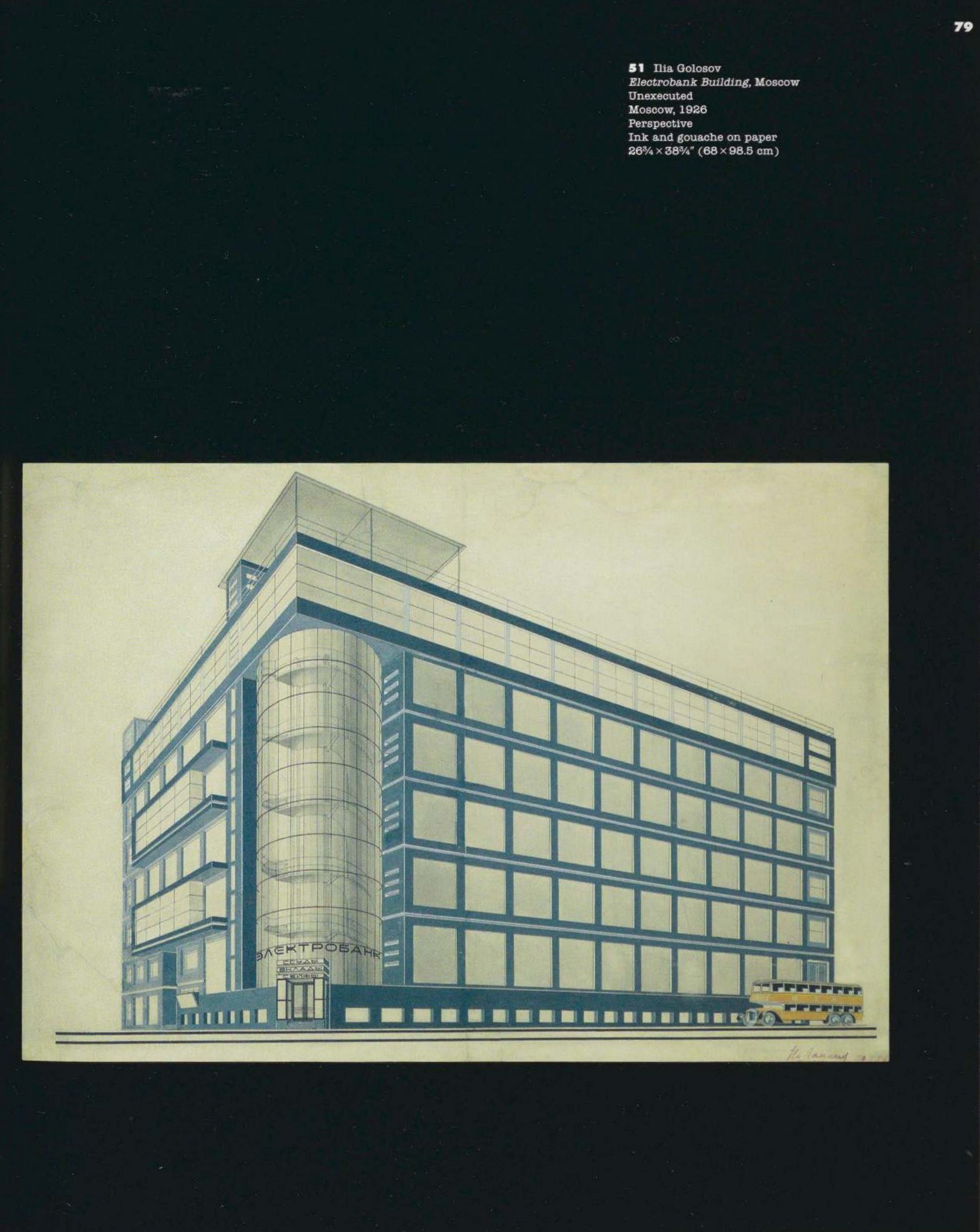

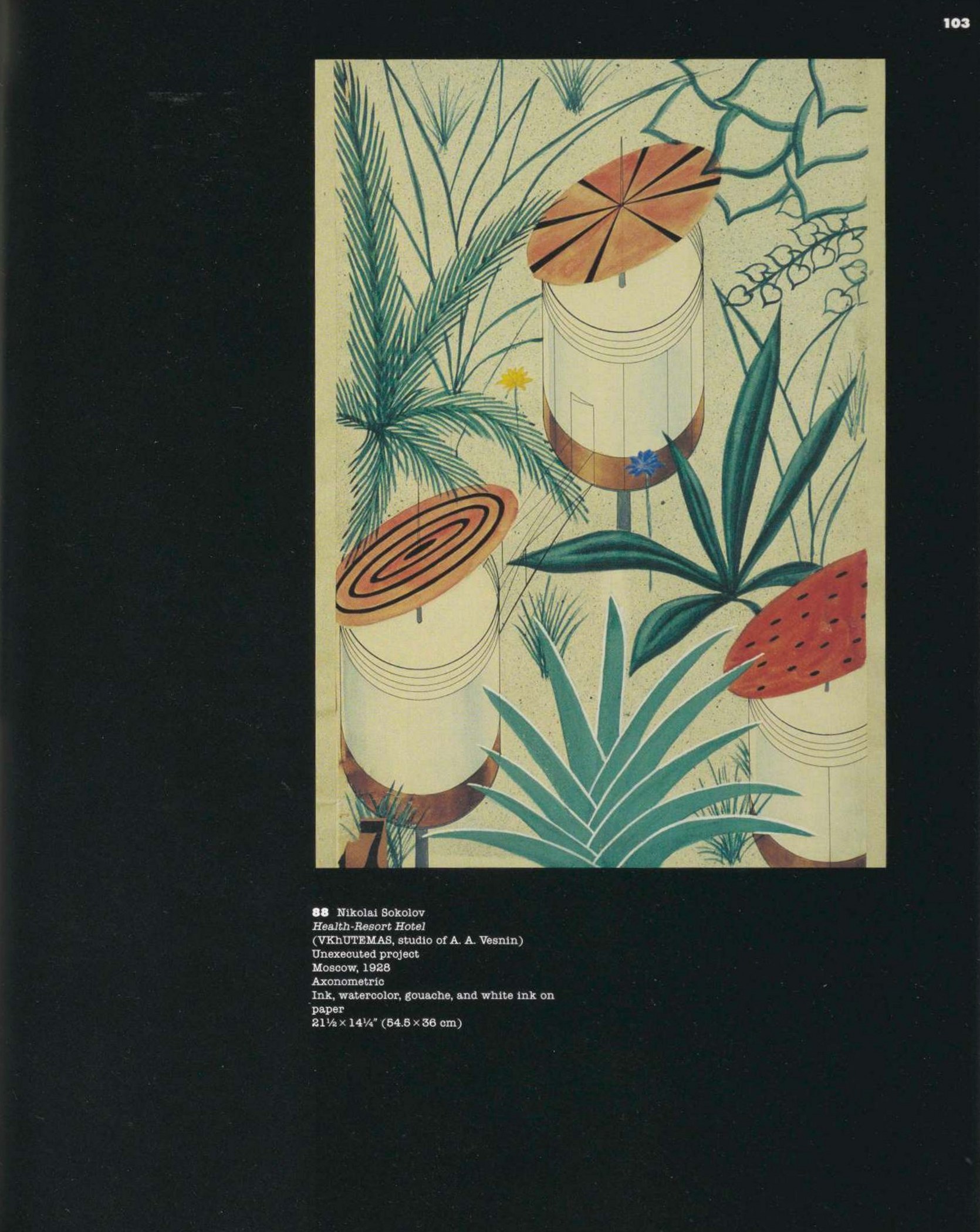

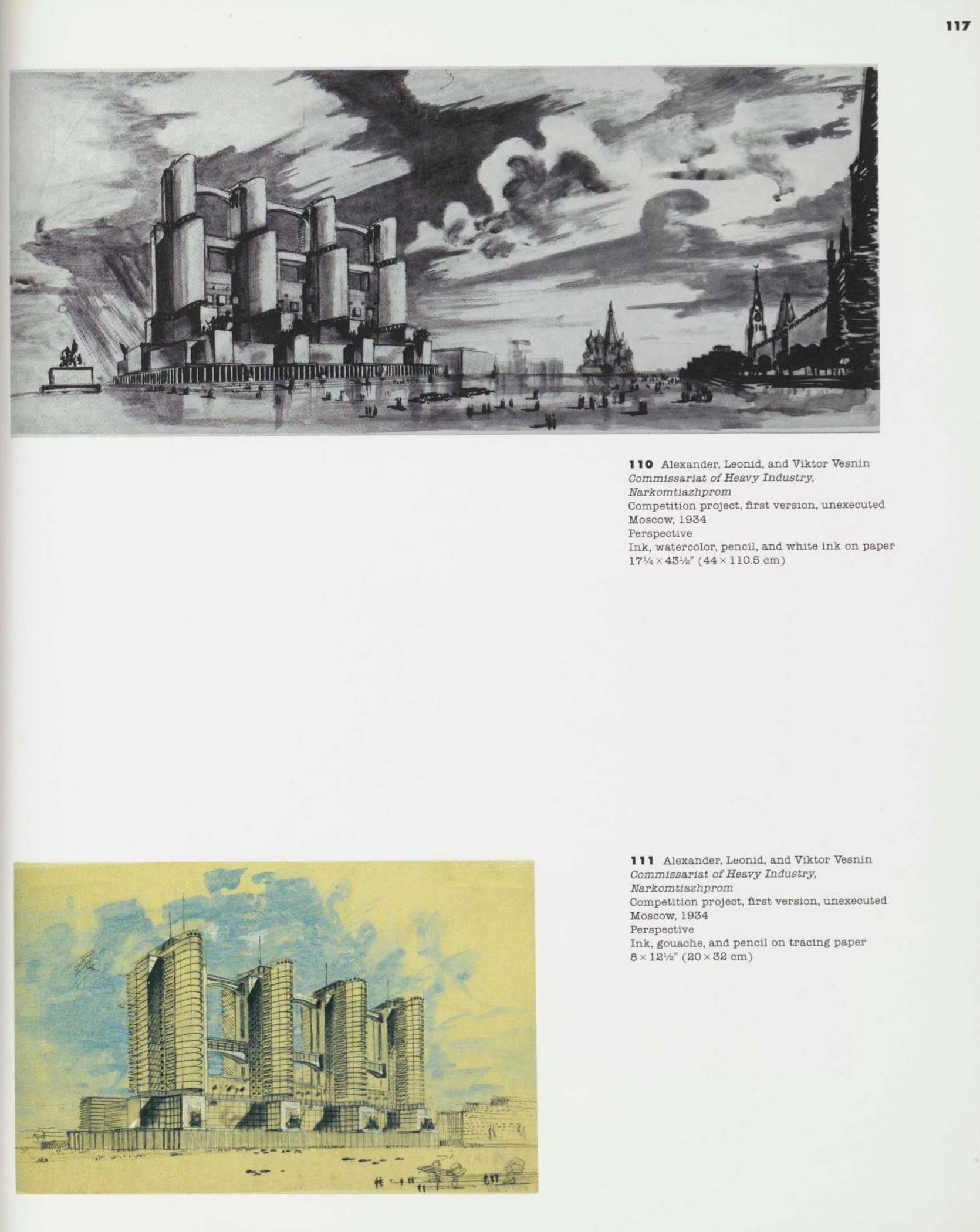

Architectural drawings of the Russian architectural avant-garde. — New York, 1990Architectural drawings of the Russian architectural avant-garde / Еssay by Catherine Cooke. — New York : The Museum of Modern Art, 1990. — 143 p., ill. — ISBN 0-87070-556-3; 0-8109-6000-1

Essay by Catherine Cooke, with a preface by Stuart Wrede and a historical note toy I. A. Kazus.

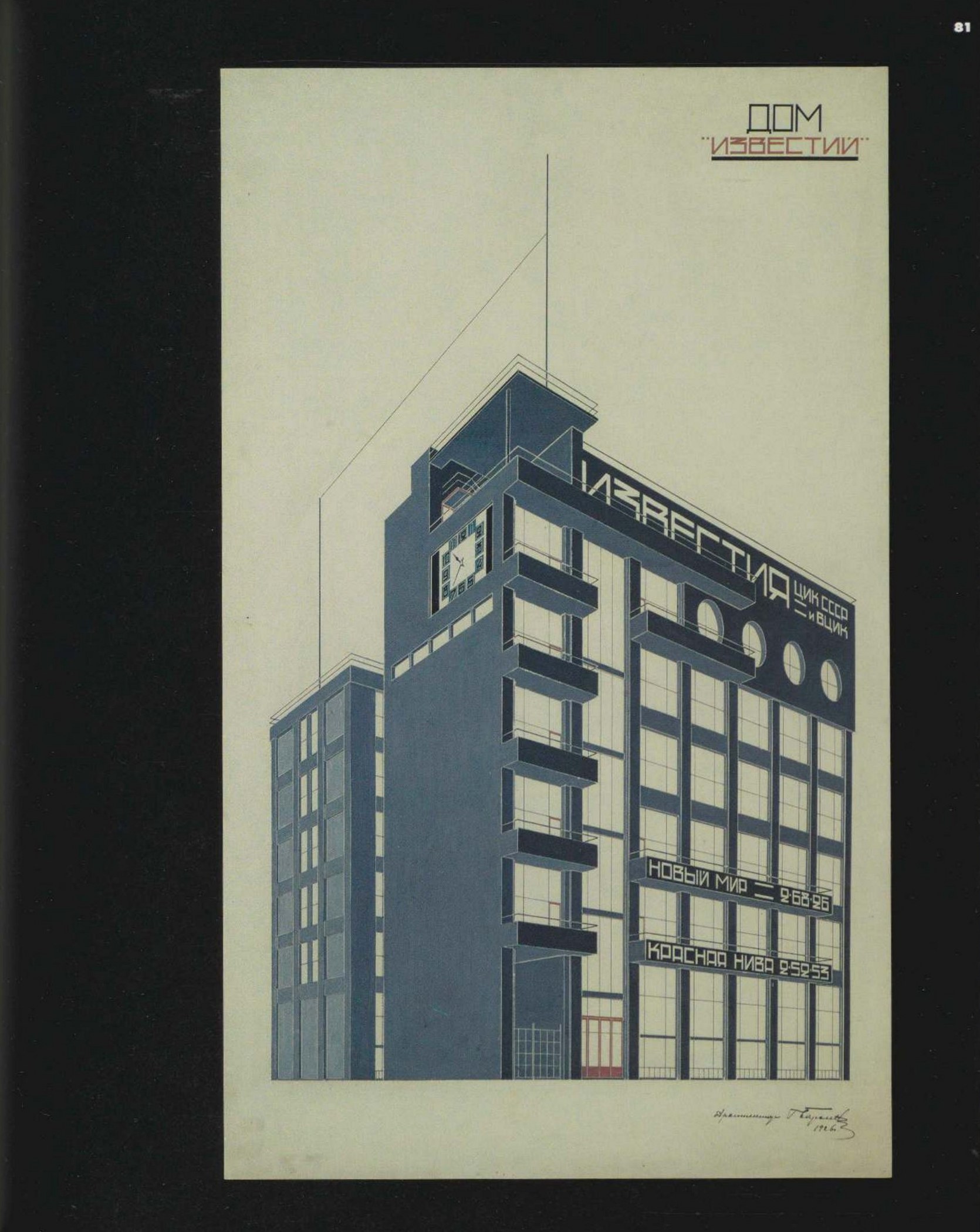

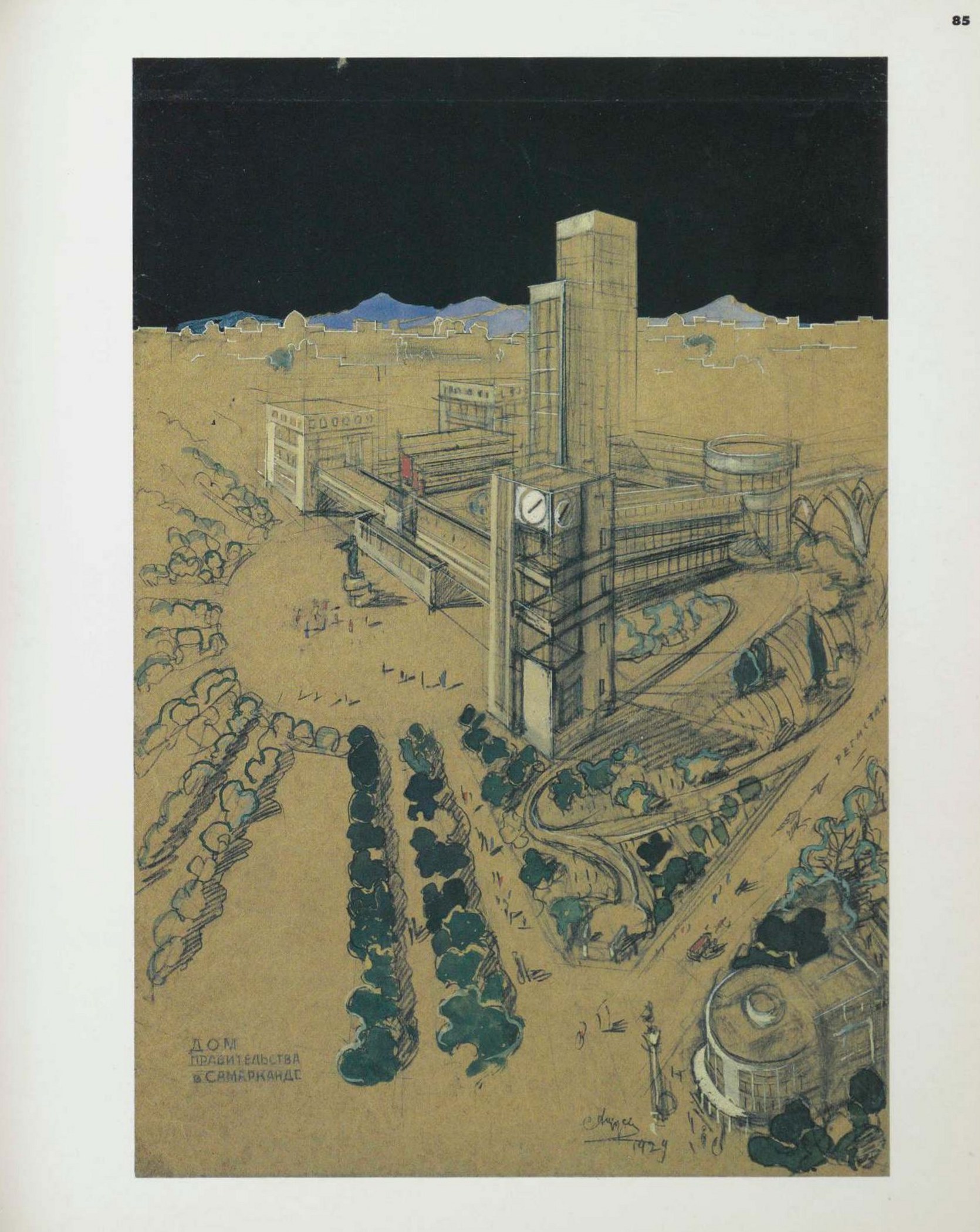

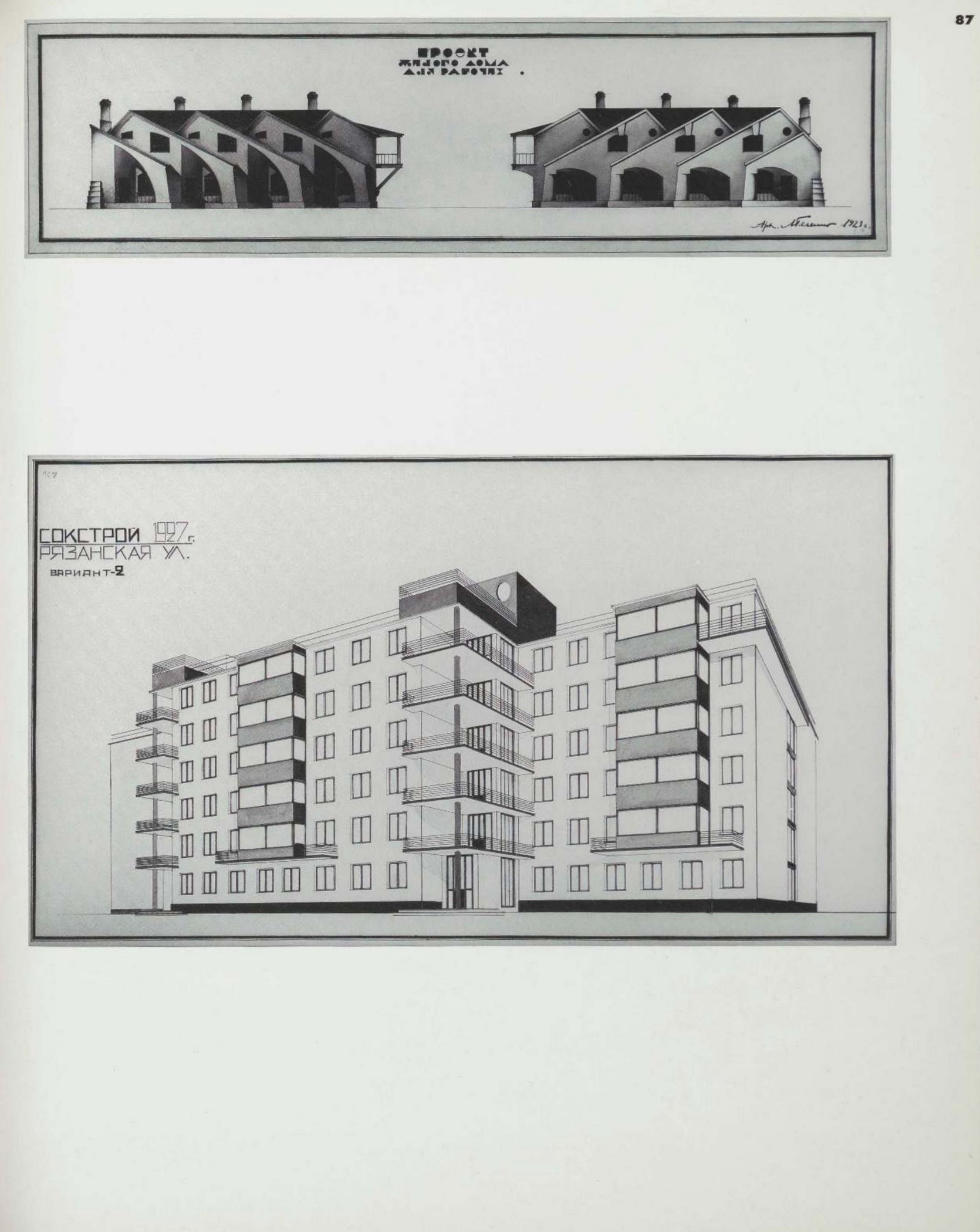

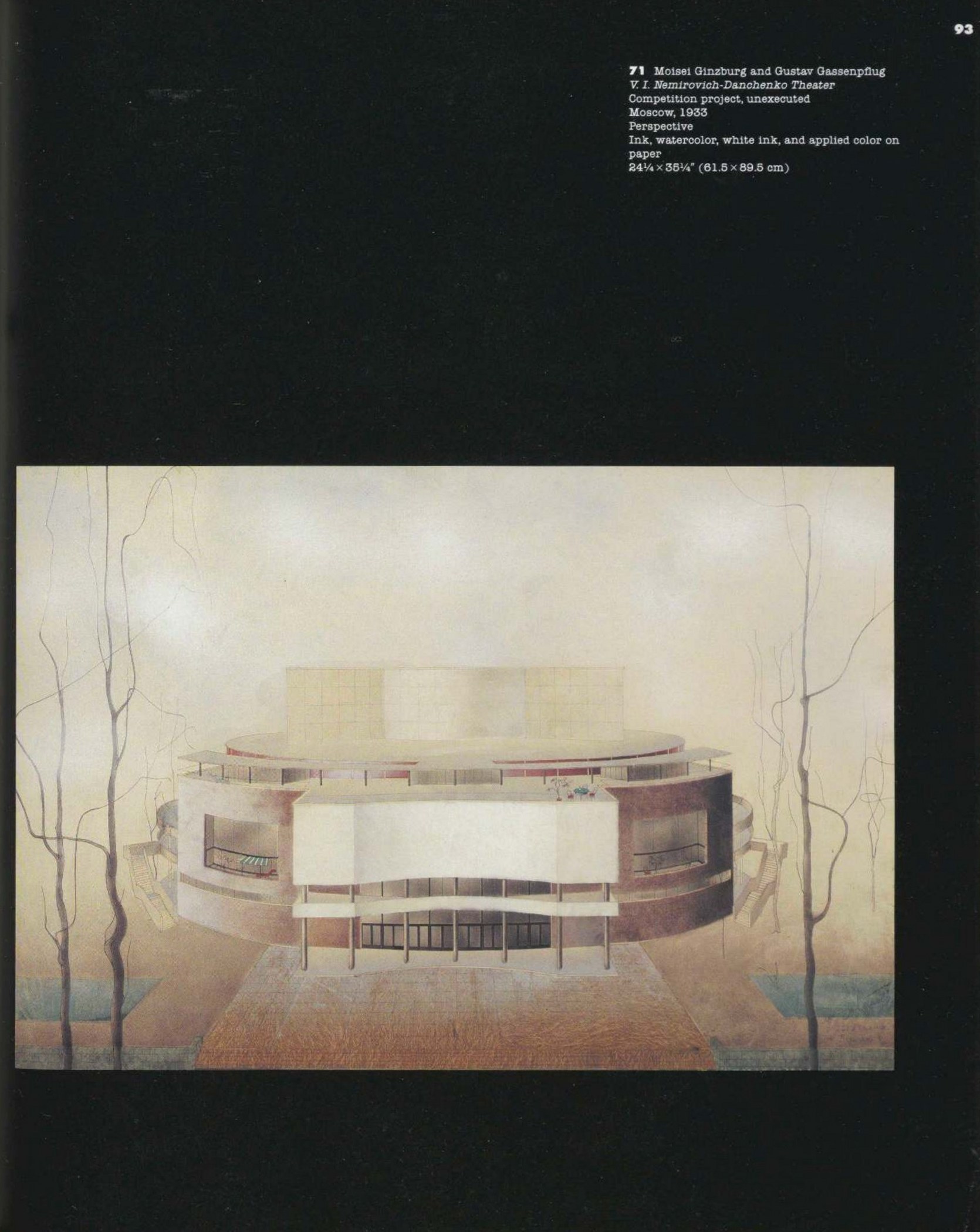

Russian avant-garde architecture of the revolutionary era stands as a unique and influential chapter in the history of modern architecture. Conceived during the tumultuous period from 1917 to 1934, when political and social revolution converged with radical revolution in the arts, much of the work—structurally daring and often utopian—was never built. It Is now known principally through the powerful and vividly executed drawings that are the subject of this book. Illustrations include works by Ivan Leonidov, the Vesnin brothers, Konstantin Melnikov, Moisei Ginzberg, and some thirty other architects.

Catherine Cooke is a consultant editor of Architectural Design, London, a Lecturer in Design in the Faculty of Technology at the Open University, Great Britain, and is widely known as a specialist on Soviet architecture. In her essay she explores the milieu in which these architects practiced and built, their close relationship with avant-garde painters such as Kazimir Malevich and Vladimir Tatlin, and the competitions for such projects as the Palace of Labor, the Palace of Soviets, and the Commissariat of Heavy Industry. Her account also explores the ongoing debate in the 1920s between the modernists and the traditionalists, or Socialist Realists, and the logic of eventual conservative reaction as Stalin consolidated his power in Russia.

The remarkable drawings reproduced here are from the A. V. Shchusev State Research Museum of Architecture in Moscow, the principal repository of such material in the world. The publication of this book has been occasioned by a major loan exhibition organized by The Museum of Modern Art, the first presentation in the United States of works from the Shchusev Collection. It is also the first time that all the most important drawings of the Russian avant-garde period in this collection have been exhibited outside of Russia.

Preface

The work of the Russian avant-garde during the years 1917 to 1934 constitutes an extraordinary chapter in twentieth-century art and architecture. From the outbreak of the Bolshevik revolution to the avant-garde’s ideological demise under Stalin, it was a period when radical changes in the arts converged with social and political revolution.

Like most of its compatriot vanguard movements In Europe, the Russian avant-garde drew inspiration from the innovations of Cubism before World War I. And like these movements it fostered an intimate collaboration and cross-fertilization among the arts. Not only the fine arts and architecture but also photography, films, industrial design, and graphics thrived in this period. The Russians had their own unique talents in the artists Kazimir Malevich and Vladimir Tatlin, both of whom had a direct influence on architecture.

The accession to power of a revolutionary government that set about transforming the social order gave the architectural profession an opportunity, through competitions and commissions, to redefine architecture’s social and cultural role. At the time these developments captured the imagination of modern architects internationally who, especially In Europe, were still functioning within an essentially conservative bourgeois social order. Among those who did work in Russia were Le Corbusier, Hannes Meyer, and Ernst May.

While this confluence of artistic and political revolution retains a strong hold on our imagination, it is not enough to account for the continuing powerful attraction of this architectural work. Rather, it is the formal inventiveness and high aesthetic level of the projects, as well as their range, that capture our attention today. Germany was perhaps the only other country in the 1920s with an equal number of architects committed to modernism. But unlike their generally “sachlich” approach, much of the Russian work displays a conceptual and structural daring that in the finest examples, such as the designs of Leonidov, ascends to a spiritual realm. Their work, however, belied the lack of a modern technical and material base to sustain these visions into built structures. Perhaps, as in the case of the Futurists in Italy, the country’s technological backwardness was liberating.

Central to this spirit of daring Innovation were schools such as the VKhUTEMAS with their open and experimental teaching program staffed by leading members of the various avant-garde groups. Equally if not more radical than the Bauhaus, the VKhUTEMAS was from the outset considerably more involved in the training of architects than was its German counterpart.

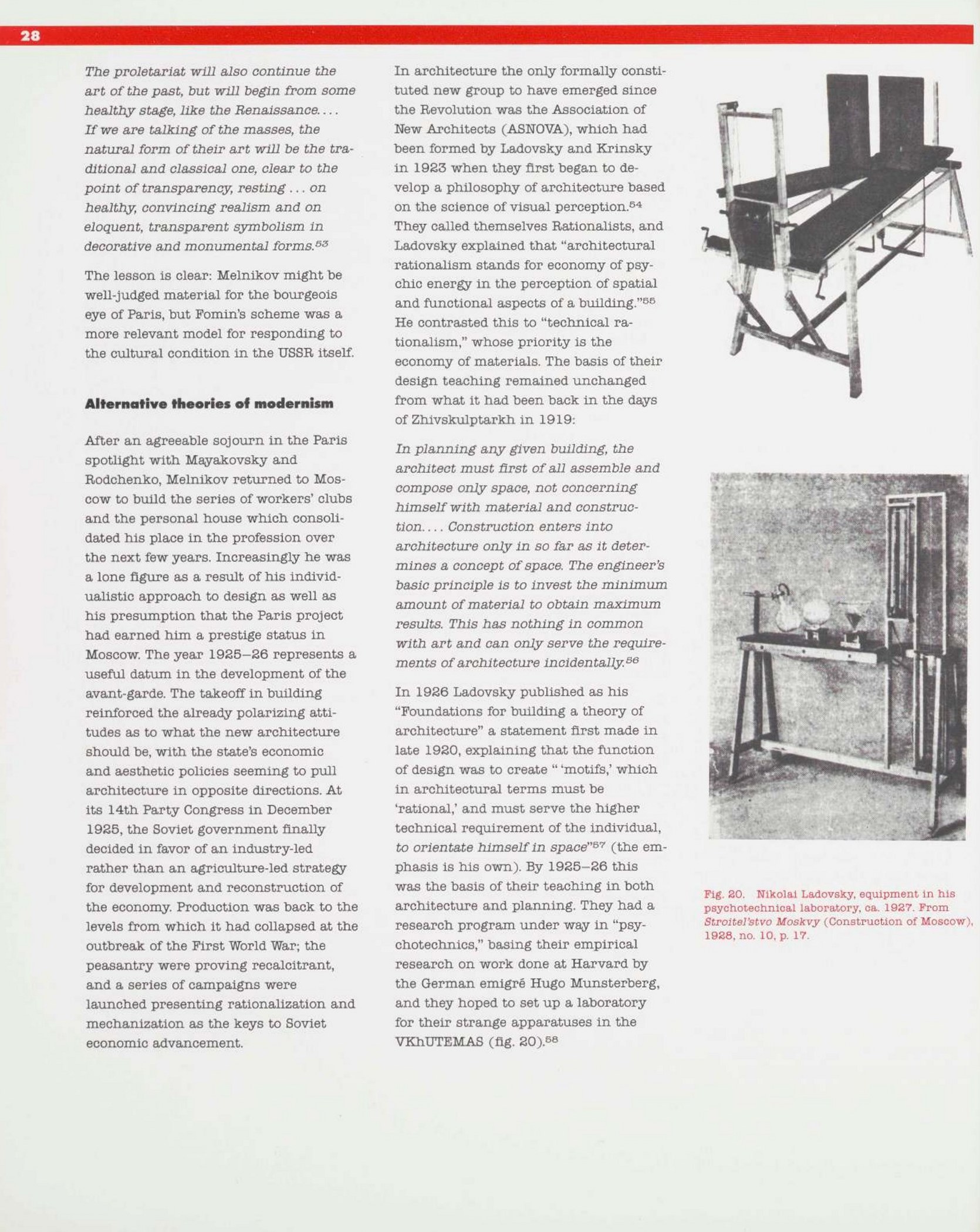

In her essay for this catalogue Catherine Cooke has admirably presented the richness of the theoretical and ideological debates both within the avant-garde as well as between its members and the emerging Socialist Realists. The arguments between a “rationalism” based on formal, spatial, and psychological considerations and one based on structural and functional concerns, as well as between modernists and traditionalists, seem to have a certain current relevance and cast the present-day architectural debates into perspective.

Inexplicably the first standard histories of modern architecture by Siegfried Giedion, Nikolaus Pevsner, and Henry-Russell Hitchcock left out the Russian avant-garde. Even Reyner Banham’s seminal Theory and Design in the First Machine Age of 1960 barely touched on the subject. The difficulty of doing research in Russia at the time and the climate of the early cold war may have been partly to blame. The work was not rediscovered in the West until the 1960s with the publication of books such as Anatole Kopp's Ville et revolution (1967), as well as the 1970 landmark exhibition, "Art in Revolution," organized by the Arts Council of Great Britain at the Hayward Gallery in London. Since then an increasing number of articles and books in the West, and also by Russian scholars, notably S. O. Khan-Magomedov’s Pioneers of Soviet Architecture, have helped provide a fuller and more detailed picture of this work.

Despite this increased attention, the projects of the Russian avant-garde architects have become familiar to us mainly through grainy black-and-white photographs. Not until recently have any of the original drawings been available for exhibition. The A. V. Shchusev State Research Museum of Architecture in Moscow, from whose archives we have been so generously allowed to select drawings for this exhibition, is the largest repository of such material in Russia, indeed in the world. While the Shchusev collection is not comprehensive, it is a most representative collection of the avant-garde architectural activity of this period and includes some of its finest work. Segments of the collection have been shown in Europe, but this is the first time the original drawings are on view in the United States, as well as the first time that all the most important drawings of the avant-garde period in the collection have been seen together in one exhibition. The work of some thirty-five architects is represented in the exhibition, another important testament to the scope of this remarkably creative period.

I am most grateful to the Shchusev State Research Museum of Architecture in Moscow for so generously lending us this unique collection of architectural drawings and to Igor Kazus, Acting Director, and Alexei Shchusev, former Director of the museum, for their enthusiasm and support in making the exhibition possible. I am equally grateful to Yevgeny Rozanov, Minister of the State Commission on Architecture and Town Planning, for his support.

It has been a particular pleasure to work with the curatorial and administrative staff of the Shchusev Museum. My thanks to Lev Lyubimov for his efforts in coordinating the work at the museum, to Marina Velikanova and Dotina A. Tuerina for helping to review the drawings in the archives and for preparing the initial checklist and architects' biographies, to Karina Yer Akopiar and Irina Chepuknova for showing me the drawings on my two initial visits and for so kindly introducing me to the avant-garde architecture in Moscow.

Special gratitude must go to Kevin Roche, who first told us about the drawing collection at the Shchusev and then generously provided the support for a first exploratory trip to Moscow to review the material.

At The Museum of Modern Art I am grateful to Richard Oldenburg, Director, for his efforts toward the realization of this exhibition, James Snyder, Deputy Director for Planning and Program Support, and Richard Palmer, Coordinator of Exhibitions, contributed vital administrative support for the project. I also wish to thank Sue Dorn, Deputy Director for Development and Public Affairs, and her staff; Jeanne Collins, Director of Public Information; Waldo Rasmussen, Director of the International Program, and Carol Coffin, Executive Director of the International Council; Ellen Harris, Deputy Director of Finance and Auxiliary Services; Aileen Chuk, Administrative Manager in the Registrar’s office; Jerome Heuner and the exhibition production and framing staff; Michael Hentges, Director of Graphics; Joan Howard, Director of Special Events; and Emily Kies Folpe, Museum Educator/ Public Programs. Their efforts have all been invaluable to the success of the exhibition and related events.

For their essential assistance in the preparation of the catalogue I am grateful to the staff of the Publications Department: Janet Wilson, Associate Editor, and Pamela Smith, Associate Production Manager, as well as Harriet S. Bee, Managing Editor; Tim McDonough, Production Manager; and Haney Kranz, Manager of Promotion and Special Services, It has been an equal pleasure to work with Janet Odgis, the designer of this very handsome volume.

Special thanks to Catherine Cooke for the main catalogue essay, which elegantly places the architectural projects in the context of their time. In addition, she has served as a most valuable adviser to the exhibition. Igor Kazus has also contributed an informative history of the Shchusev Museum and its collection. Andrew Stivelman has provided translations from the Russian texts, biographies, and checklists. Magdalena Dabrowski, Associate Curator in the Department of Drawings, has been a valuable consultant on the Russian texts.

In my own department I am grateful to Marie-Anne Evans and Ona Nowina-Sapinski for their unfailing support, and to Matilda McQuaid, Christopher Mount, and Robert Coates for their help in the production of the exhibition.

Finally, of course, an exhibition and catalogue of this scope are not possible without the commitment of an enlightened sponsor. I wish to thank Knoll International, Inc., and its chairman, Marshall Cogan, for the enthusiastic support of this exhibition.

I am most grateful for additional support from Lily Auchincloss, and also from The International Council of The Museum of Modern Art, the national Endowment for the Arts, and the Trust for Mutual Understanding. The Contemporary Arts Council of The Museum of Modern Art has kindly provided support for the related symposium.

Stuart Wrede

Director

Department of Architecture and Design

Contents

6 Preface. Stuart Wrede

9 Images in Context. Catherine Cooke

49 Plates

128 A History of the A. V. Shchusev State Research Museum af Architecture. I. A. Kazus

131 Biographies of the Architects

140 Selected Bibliography

143 Trustees of The Museum of Modern Art

Sample pages

Download link (pdf, yandexdisk; 31,6 MB).

Source: moma.org

2 июня 2018, 17:39

0 комментариев

|

Партнёры

|

Комментарии

Добавить комментарий