|

|

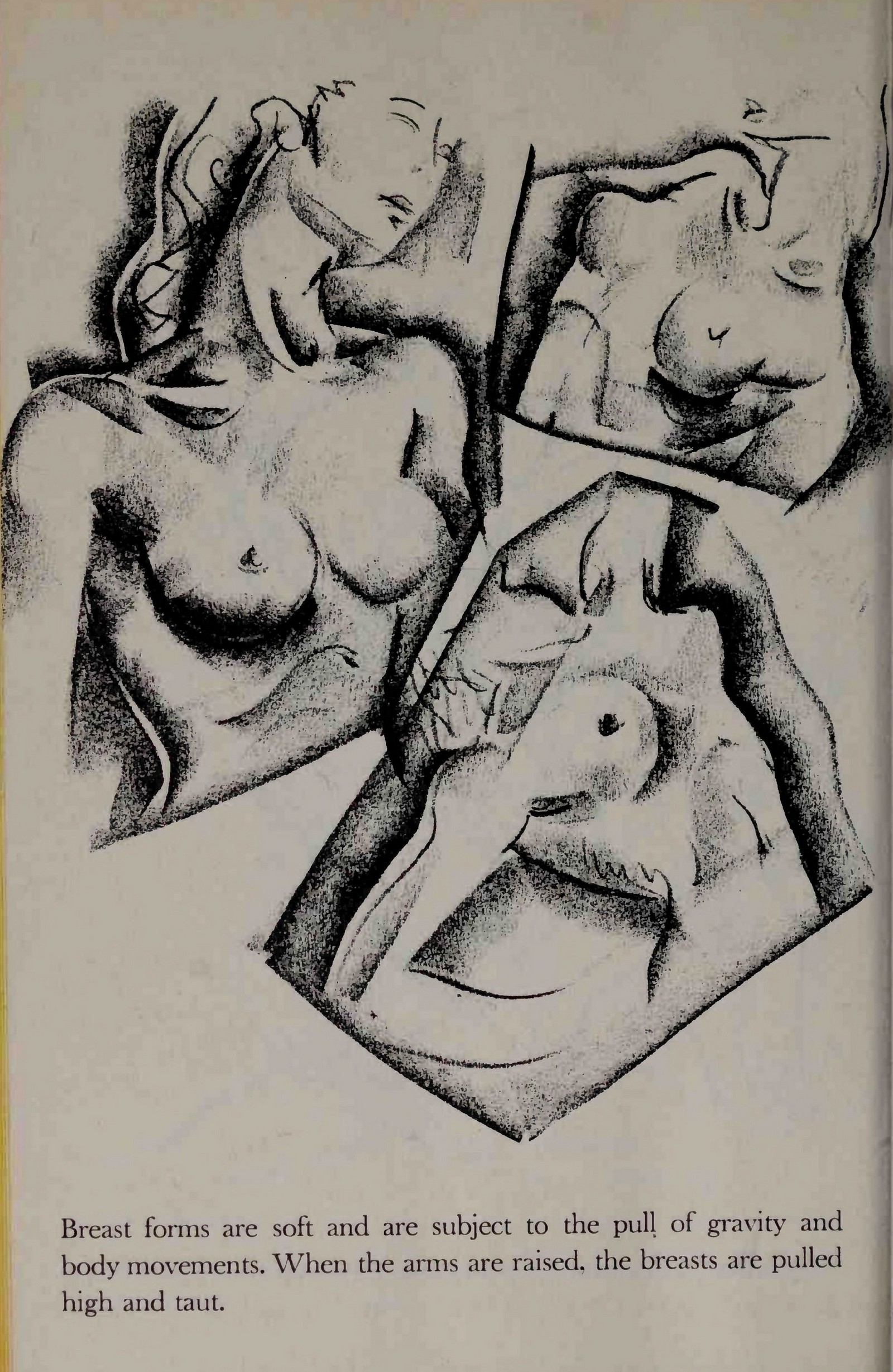

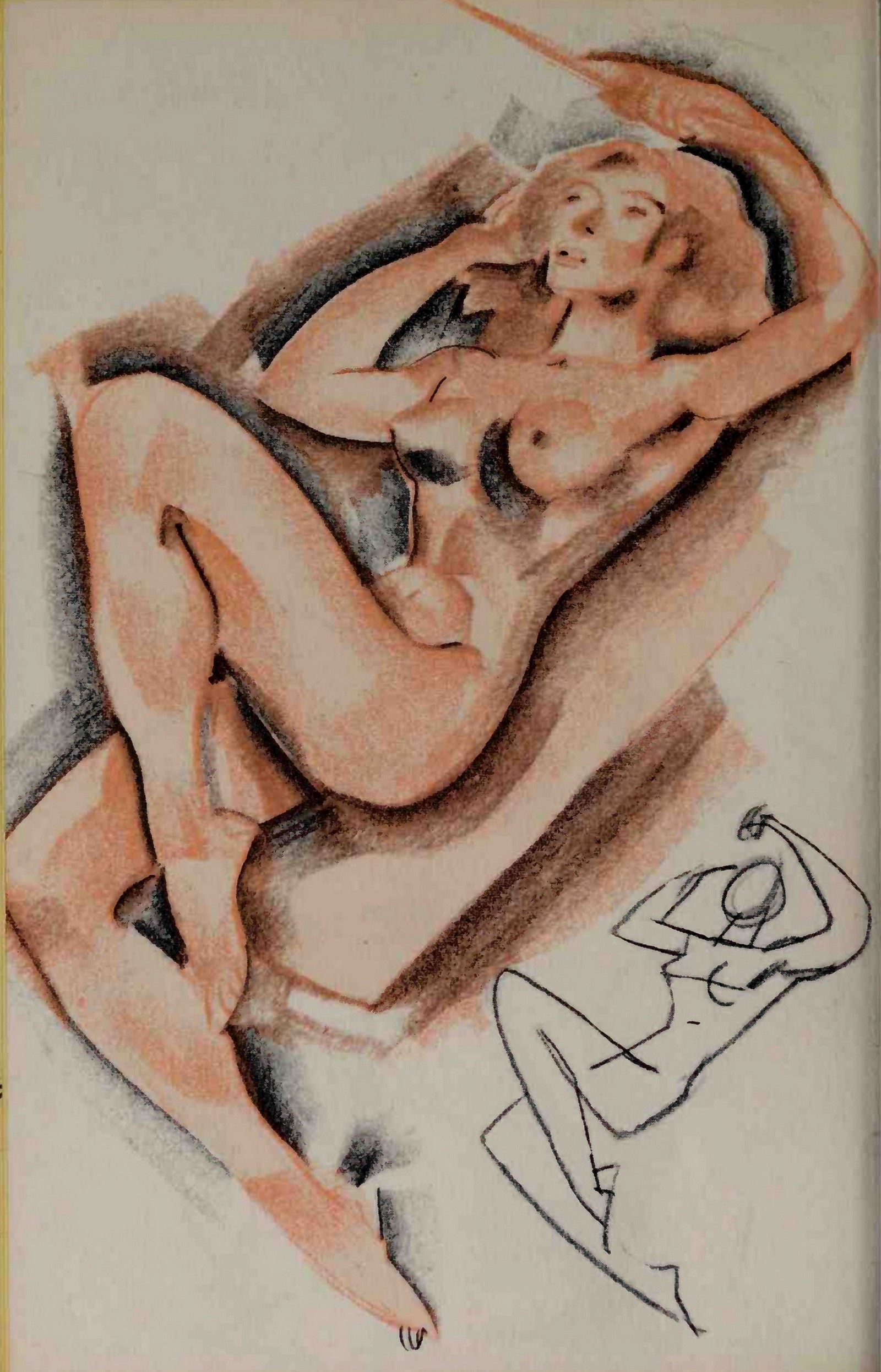

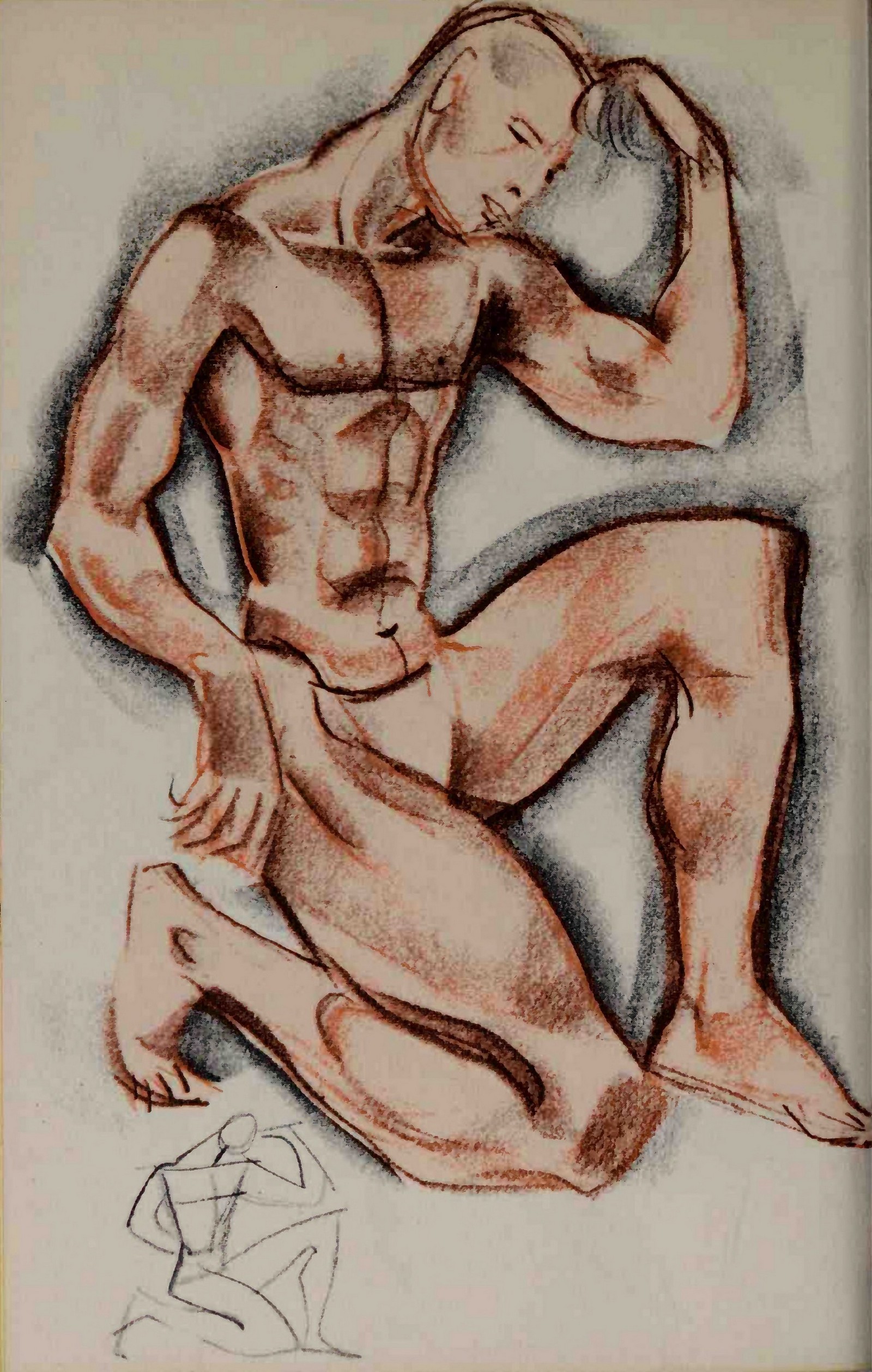

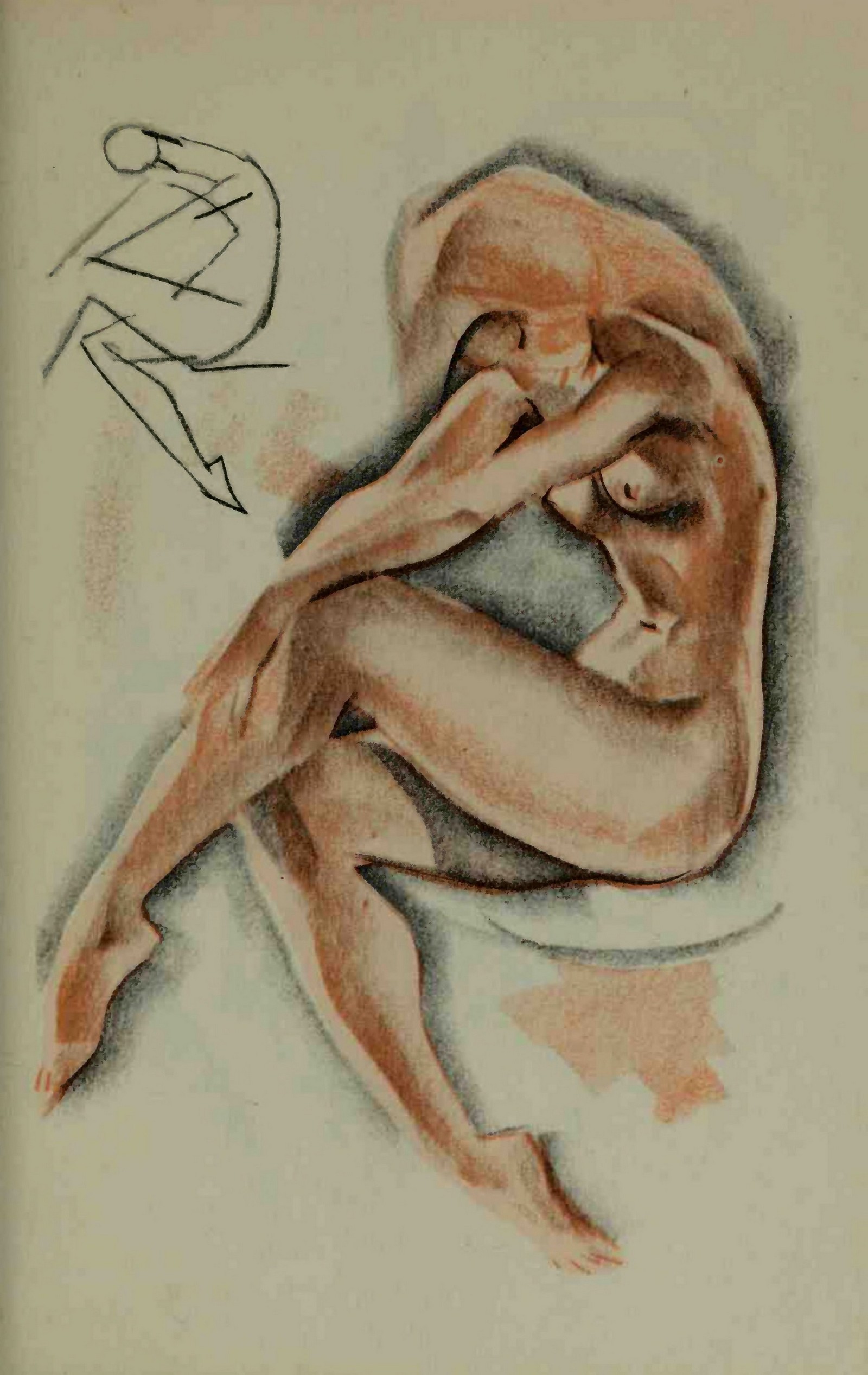

Arthur Zaidenberg. Drawing Self-Taught. — New York, 1954Drawing Self-Taught / Arthur Zaidenberg. — Cardinal edition. — New York : Pocket Books, Inc., 1954. — 172 p., ill.About author

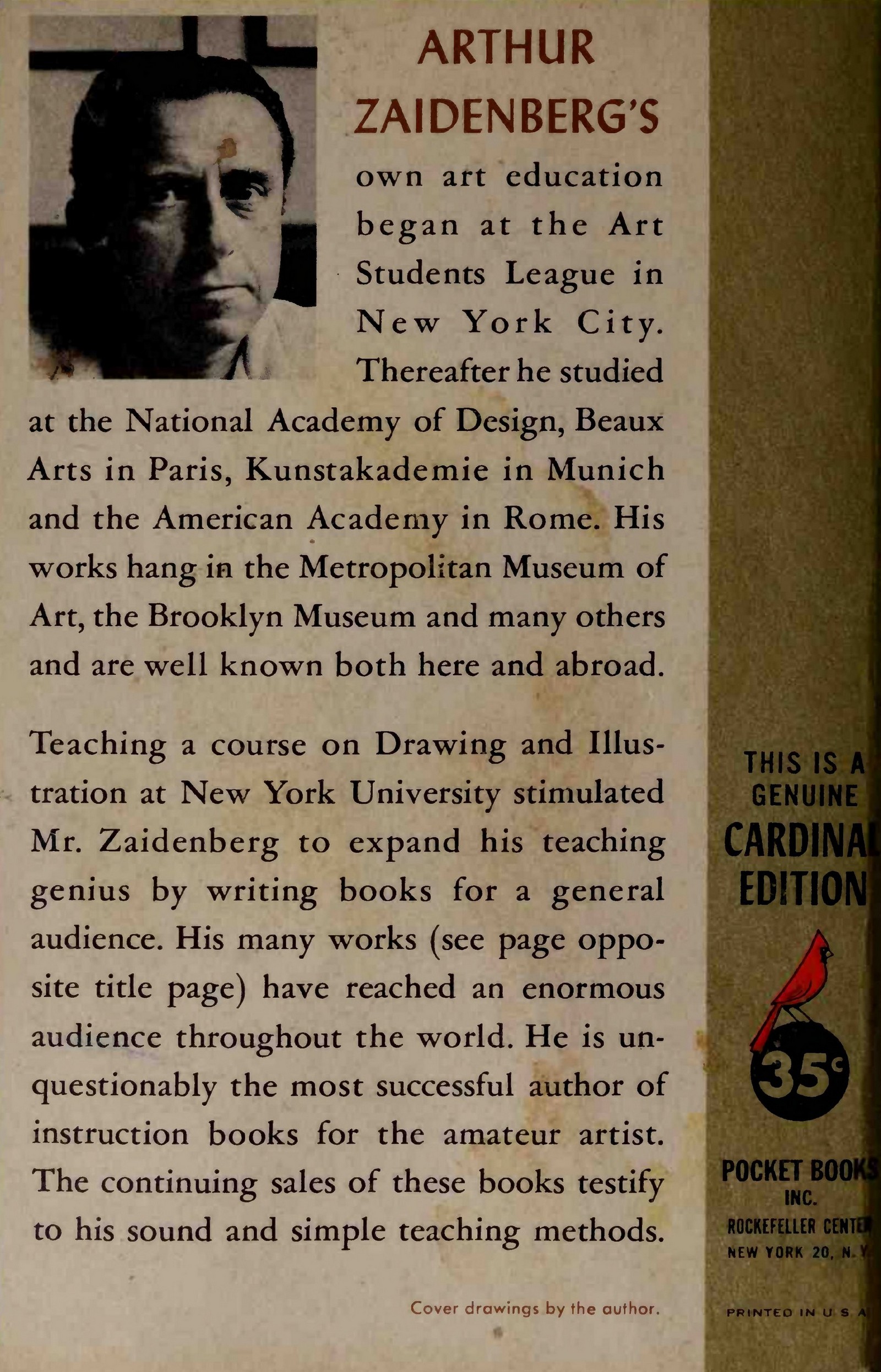

ARTHUR ZAIDENBERG'S own art education began at the Art Students League in New York City. Thereafter he studied at the National Academy of Design, Beaux Arts in Paris, Kunstakademie in Munich and the American Academy in Rome. His works hang in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Brooklyn Museum and many others and are well known both here and abroad.

Teaching a course on Drawing and Illustration at New York University stimulated Mr. Zaidenberg to expand his teaching genius by writing books for a general audience. His many works have reached an enormous audience throughout the world. He is unquestionably the most successful author of instruction books for the amateur artist. The continuing sales of these books testify to his sound and simple teaching methods.

WHY DRAW?

If you acquire even a small ability to draw whatever you wish, you have learned a new language—one in which you can converse with anyone in the world.

If you use drawing as a language you are using it properly—in its richest sense, its highest purpose. I do not mean by this that a drawing must simulate an object so faithfully that it will serve in place of the real object. Nor do I mean that your drawing must be so representational that it will replace the word description and act as an item in a picture dictionary.

The real purpose of drawing artistically is to express the impact of an object seen, filtered through your special viewpoint, your emotions, your experience and your personal taste.

You might ask “If that is what good drawing is, how can it be taught? If all I have to do is see a thing, emote about it, apply my own experience and taste, and then I can draw it, why a teacher?”

The answer is that this is true. You already possess the main ingredients toward making a good drawing, if you are observant, honest and thoughtful.

But, if you haven’t drawn much you have three qualities to acquire before you apply all of the previous virtues you possess. They are: (1) a way to see so that you can simplify the complicated things you see; (2) a method of putting down simply what you learn to see; (3) techniques in the use of the tools of the artist.

These three things you must learn. There are several methods of learning these things. The methods demonstrated here are my own. There are others, but it has been my experience that if you follow the simple steps to acquire the three added ingredients to what you already possess, and you practice them as outlined here, you will learn to draw.

DRAWING

There is no “secret” to the process of making good drawings. There is no one formula or hundred formulae which anyone can give you which will cover all the possible approaches to drawing well.

One of the greatest virtues of art is that no two works of art are exactly alike, and each man’s work is as individual as each man's signature.

If you tried to draw exactly like anyone else you would be a mere imitator and it would be a crime against your own individuality. Each artist has something of a very personal nature to say in every line he makes, and each man would be an artist if he were true to his personality and expressed his most honest conception in drawing his own way. From that point of view it is not too extravagant to state “Everyone is potentially an artist.”

The true potential of every man has yet to be tested. Latent skills are smothered by time limitations, cultural vacuums, fears and apathy in all of us. We become specialists to the exclusion of all other rich interests, and we justify our neglect of facets of our personality, untried and ignored. This results in a loss to ourselves and to the world which cannot be calculated but is certainly enormous.

The foregoing statement does not imply that anyone can be as good an artist as any other. There are inevitably the great and the lesser in every field and that is very fortunate. Uniformity of ability is not possible nor desirable. The Rubinsteins and Heifetzes do not preclude the home pianists or fiddlers who add to the audience of the talented, and produce much in the way of pleasure for themselves and others.

The amateur artist in the graphic fields has been less fortunate than the amateur musician at the hands of the “professional.” Even art teachers have, until relatively recently, been ruthless with students who have been unable to acquire the dexterity necessary for exact reproduction of posed objects and dismissed such students as hopelessly untalented.

The truth is that the potential for individual expression, latent in everyone, can be squelched with ease by an unsympathetic attitude. Fortunately, in recent years there has been a tremendous growth in amateur expression in drawing and painting. There has been a remarkable emergence of major talents and a growing increase of the minor talents. Along with this growth of interest in amateur painting has come a corresponding growth of interest in the works produced by an increasing number of “professionals.” And from my viewpoint this is all to the good.

Such instruction in drawing as will be given in this book will be directed toward removing the formidable barriers that precedents set by outmoded standards, and the even more formidable obstacle of our over-detailed vision, put in the way of the art student.

The first obstacle, that of the previous standards which restricted drawing to the professional, we can dismiss with ease. The second obstacle, our tendency to complicate rather than simplify, is less easily disposed of. But in the succeeding pages, we shall try to reduce to the simplest terms of line and form such highly complicated things as the parts of the human body and many commonplace objects which we encounter daily but never really “see.” Learning to “see,” in terms which are translatable to paper, will be our chief concern. Once you acquire a pattern for such “seeing,” the doing will be up to you.

What comes of it will be, at the very least, a great deal of fun for you; at the most, a source of pleasure to the world.

The pencil is the commonest and, at the same time, one of the most beautiful tools for drawing. It has the widest possibilities for expression of the most subtle to the boldest lines and tones.

The fact that we are all accustomed to the use of pencils removes one of the drawing beginner's greatest hazards, the fear of the unfamiliar materials of the artist.

We all have a certain resistance to learning anything new, even the most studious among us. This is obvious because there isn't anyone who could not do a great deal more about many things available for study. One, among the many reasons for this apathy, is the boredom of learning to use the tools before we begin to study the interesting elements of a subject. Let us start with the familiar pencil and assemble the few supplementary tools for drawing in that medium.

<...>

Sample pages

Download link (pdf, yandexdisk; 176 MB)

10 июля 2023, 14:03

0 комментариев

|

Партнёры

|

Комментарии

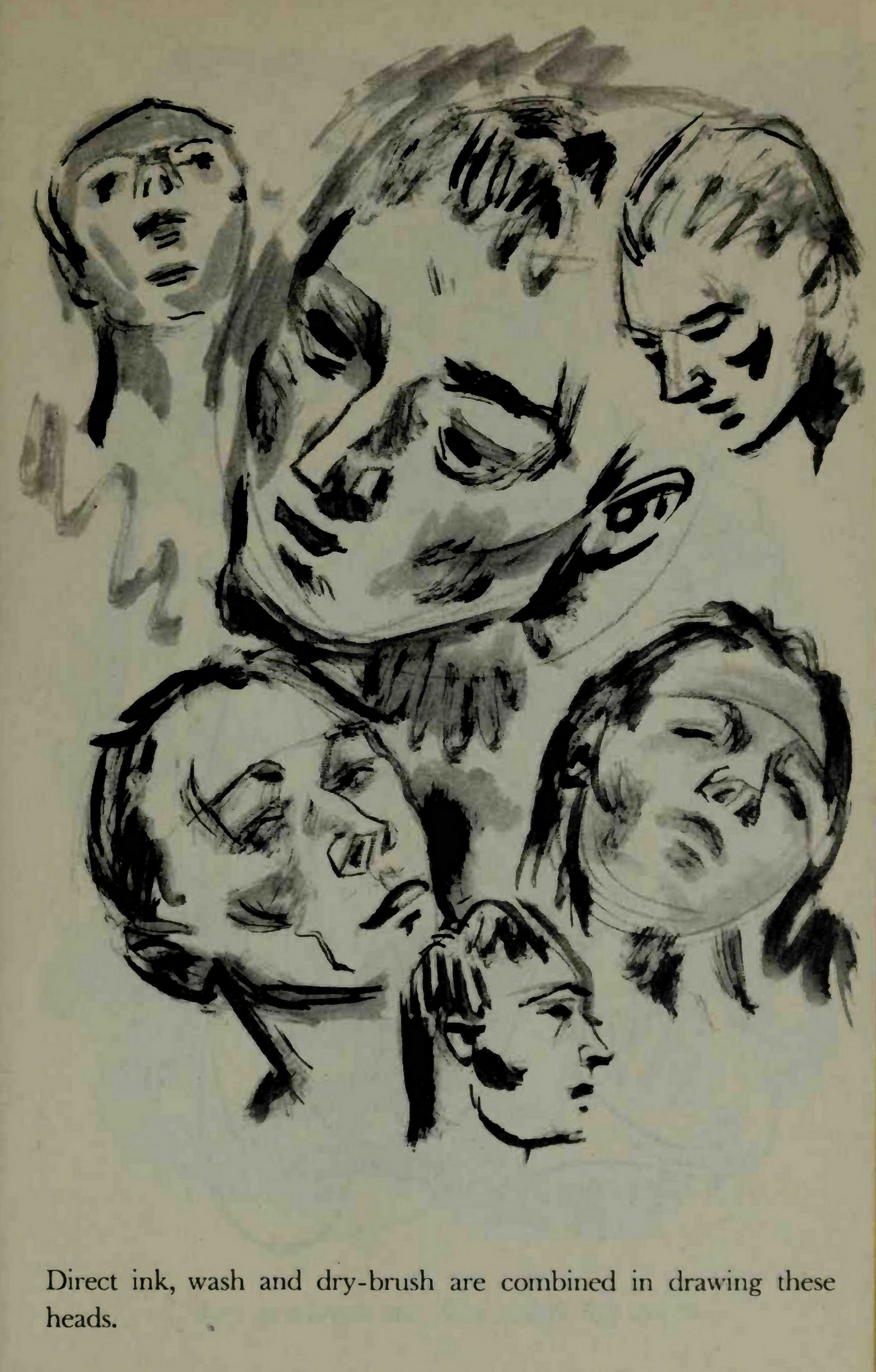

Добавить комментарий