|

|

Curtis W. J. R. Le Corbusier: Ideas and Forms. — London, 2001  Le Corbusier: Ideas and Forms / by William J. R. Curtis. — First published 1986. — London : Phaidon Press Limited, 2001. — 240 p., ill.

With 243 illustrations, including 31 in colour.

Le Corbusier (1887-1965) has been one of the dominant forces in twentieth-century architecture, and many of the forms he created have become archetypes of modernism. But he was also a social visionary and a writer of polemics, whose ideas have generated intense and partisan controversy. Le Corbusier: Ideas and Forms provides a comprehensive and unbiased survey that puts Le Corbusier in a more balanced perspective.

Making full use of the Le Corbusier archive, the author documents individual projects in detail, whilst linking the imaginative activities of the artist to his philosophy of life, to his urban visions, to his art and to the cultural predicaments of his times.

He analyses Le Corbusier’s phenomenal powers of abstraction and synthesis, showing how he created a potent architectural vocabulary based on a limited range of types and elements, and how he used it to generate architectural forms of compelling force. Close study of all Le Corbusier’s major buildings, from first sketches to final achievement, reveals the artist’s struggle to reconcile the ideal and the practical and to give institutions and ideologies a suitable symbolic form. It also reveals how this most ‘modern’ of architects constantly found inspiration in nature and in architectural tradition.

William J. R. Curtis studied at the Courtauld Institute of Art, London, and Harvard University, and has taught the history of architecture and theories of design at universities in England, the United States, Australia and Asia. His books include Le Corbusier / English Architecture (1975) and Le Corbusier at Work (1978). His best-selling Modern Architecture since 1900 was first published by Phaidon Press in 1982 (third edition, 1996).

He received the Founder’s Award of the Society of Architectural Historians (USA) in 1982. In 1985 he was the recipient of both the critics’ award of the Comité Internationale des Critiques d’Architecture and the CICA award for best article of architectural criticism world-wide in the period 1982-85. His monograph Balkrishna Doshi: an Architecture for India won him a silver medal at the world Biennale of Architecture in 1989.

PREFACE

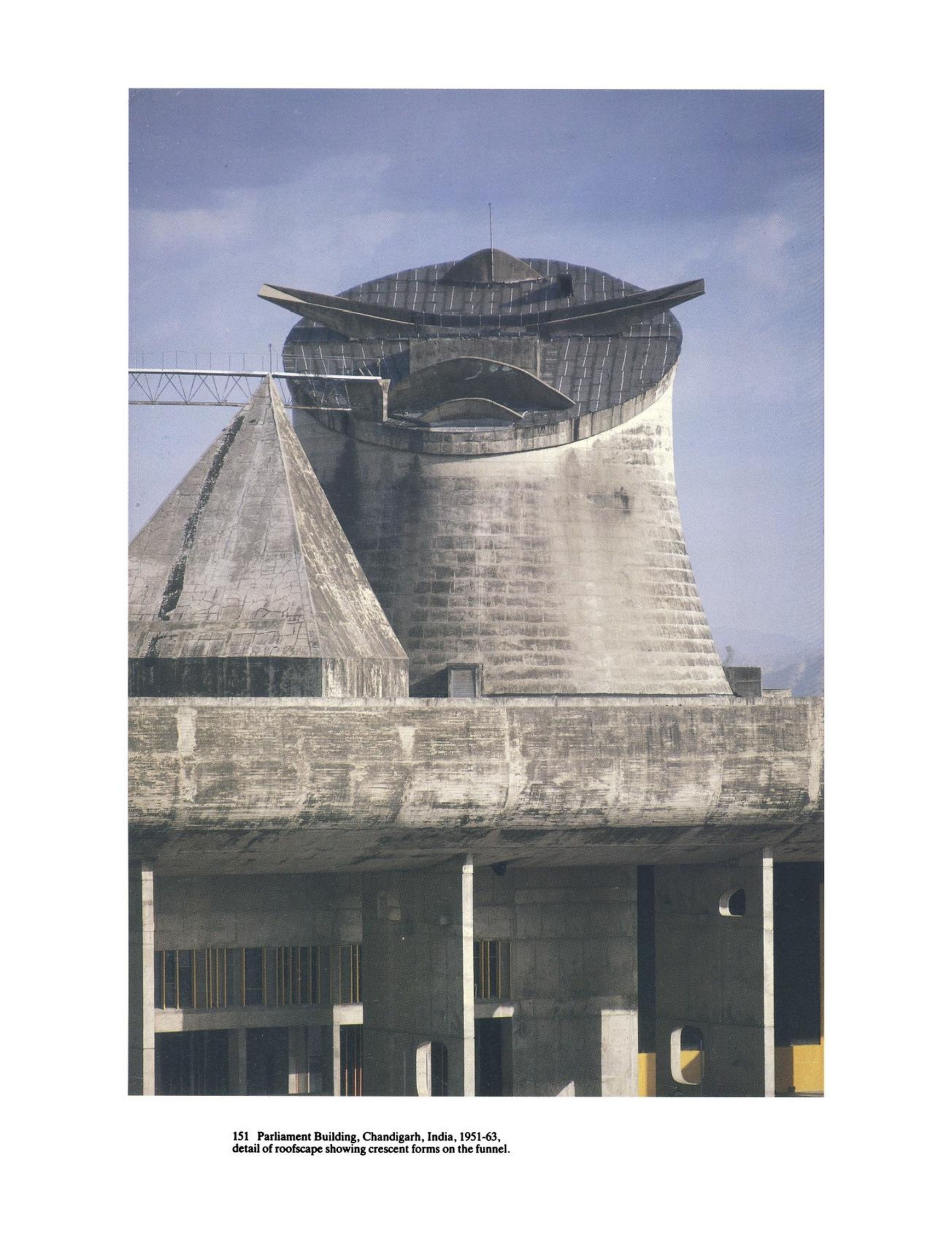

It is impossible to understand architecture in the twentieth century without first coming to terms with Le Corbusier. His buildings can be found from Paris to La Plata to the Punjab, and his influence has extended over four generations world-wide. His projects for the city have become enmeshed with the hopes, disappointments and crises of industrialization. Individual masterpieces such as the Villa Savoye at Poissy, the Chapel of Notre Dame du Haut at Ronchamp, or the Parliament Building at Chandigarh, will bear comparison with the works of any age. As well as an architect, Le Corbusier was also a painter, sculptor, urbanist and author; even a philosopher who ruminated on the human condition in the modern age. Like Freud, Joyce or Picasso he helped to give shape to the thought and sensibility of an epoch by investing his insights and findings with a universal tone. Whether we like it or not, these discoveries have now become part of our tradition.

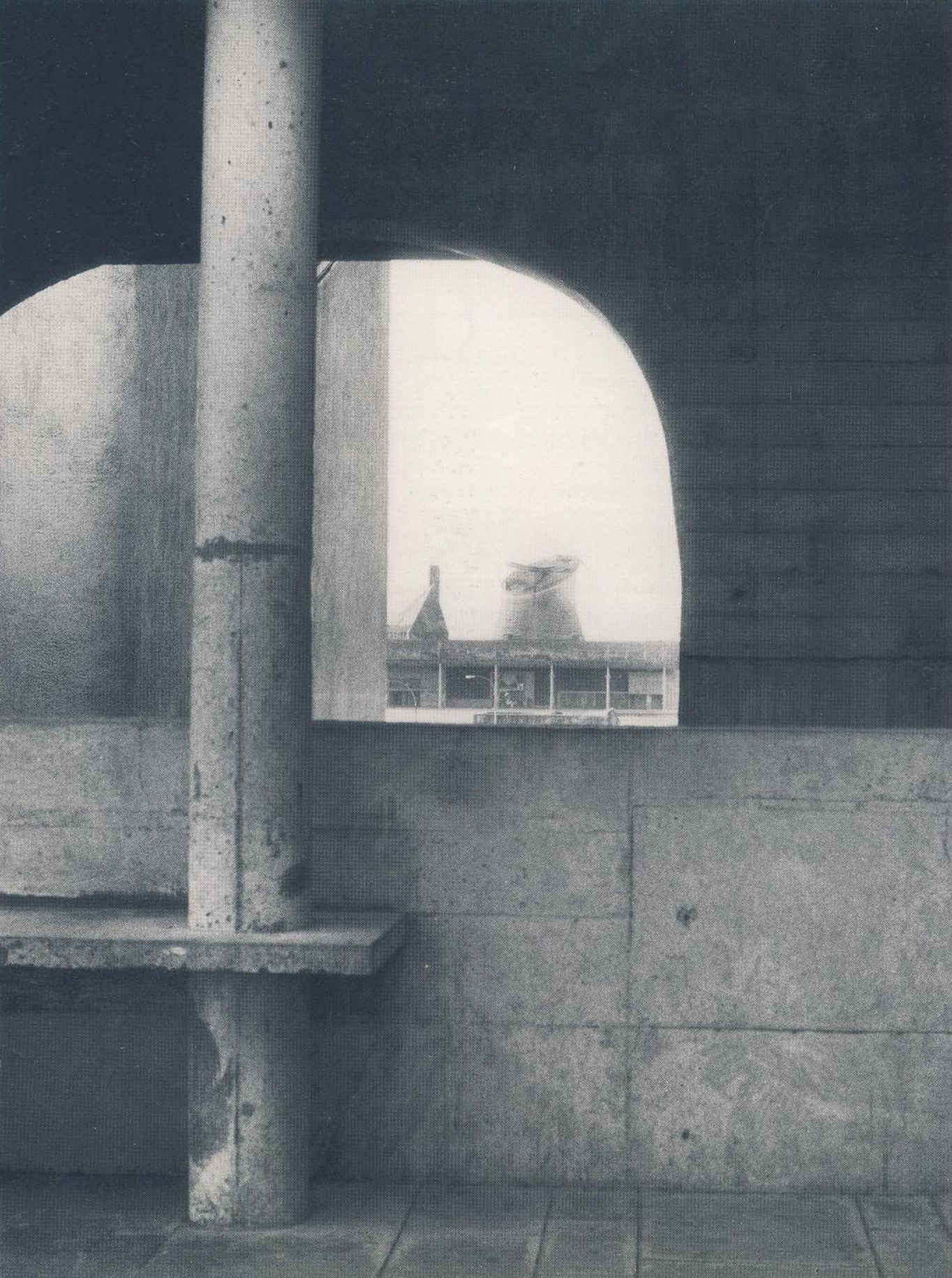

1. Chandigarh, India, 1951-65, view from the High Court towards Parliament.

Twenty years ago, when Le Corbusier died, there was a nebulous consensus that he should be regarded as the leader of world architecture. Since then his name has attracted both reverence and denigration. The faithful have put him on a pedestal, treating his buildings as edicts of wisdom. The sceptics have set out to smash the idols, concentrating less on individual works than on determinist and dictatorial aspects of Le Corbusier’s urban planning. The ‘good’ and ‘bad’ of Le Corbusier’s influence on others is a complex question that depends on prejudices and points of view, but judgements of any kind are best based on accurate information rather than the vagaries of contemporary criticism. This is a figure of unusual historical dimensions who needs to be seen in a long perspective: one of those rare individuals who have altered the assumptions of their art in basic ways.

The moment is right for a new synthesis, as the few general books of value on Le Corbusier have been eroded by the flood of new findings issuing from the archives of the Fondation Le Corbusier. In the past decade scholars have worked closely with the evidence afforded by drawings, letters and sketchbooks, and have been able to penetrate individual themes with greater depth and accuracy. Many fine fragments of scholarship are lying about, waiting to be integrated into a new general structure because the old one will no longer do. Le Corbusier needed this shake-up, for there was a tendency in an earlier generation to treat him as an unexamined fact of life. From the present perspective it is just possible to look at him as a fact of history — as a figure who continues to influence the present, to be sure, but also as a major creator in the history of art, like Palladio, Sinan or Ictinus.

Many different books could be written around someone as complex and wide-ranging as Le Corbusier. This one is called Le Corbusier: Ideas and Forms because it is concerned above all with the ways in which the architect compressed many levels of meaning into his individual buildings, treating them as symbolic emblems or microcosms of a larger world view. They crystallized general themes and employed typical elements which the architect extended and transformed on each new occasion. Their vocabulary cannot be understood apart from Le Corbusier’s activities as a painter, sculptor, urbanist and writer; nor apart from his attitudes to society, nature and tradition. He drew history, objets trouvés, ideas, through a filter which gave them a new status within the structure of his own myths. His buildings need to be understood as imaginative metamorphoses of the world.

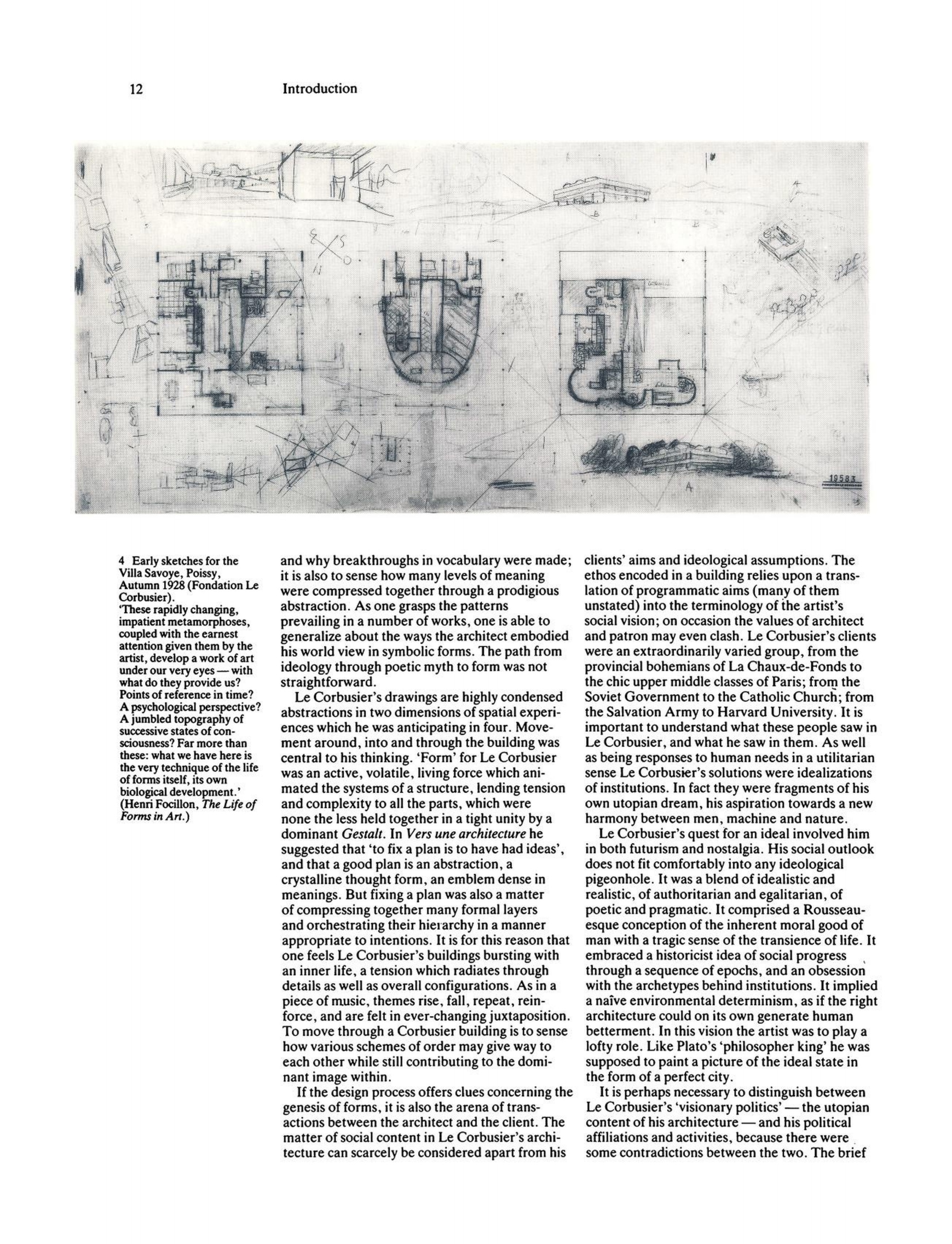

They must also be seen, of course, as solutions to a host of social, practical, technical, expressive and symbolic problems. To grasp them properly we need to reconstruct the conditions and limitations under which Le Corbusier worked. Drawings, sketches and letters enable one to reconstruct the process of design, the creative transactions between client and architect, architect and co-workers. They bring one closer to the mind of the artist, to intentions behind the individual work, and to the tensions between the ideal vision and the constraining reality. They allow one to avoid the limitations of either a simplistic social determinism or a simplistic formal determinism.

Le Corbusier’s forms in all media derived part of their authenticity from ethical and political commitments, from a driving social vision, from an idea of the way things ought to be. Although he never constructed his ideal city in toto, he did treat individual buildings as demonstrations of urbanistic ideas. He also considered it part of the architect’s job to penetrate to the deeper human meaning of building programmes and to idealize institutions. If he had not succeeded in translating his social theories into buildings of haunting power we probably would not bother to deal with his utterances on society. However, it is unlikely that his architecture could have achieved its strength without the transcending social content. Le Corbusier was neither just an ideologist nor just an aesthete: ideas prompted forms, forms, ideas. To understand this internal chemistry we have to steer towards the difficult area between the two.

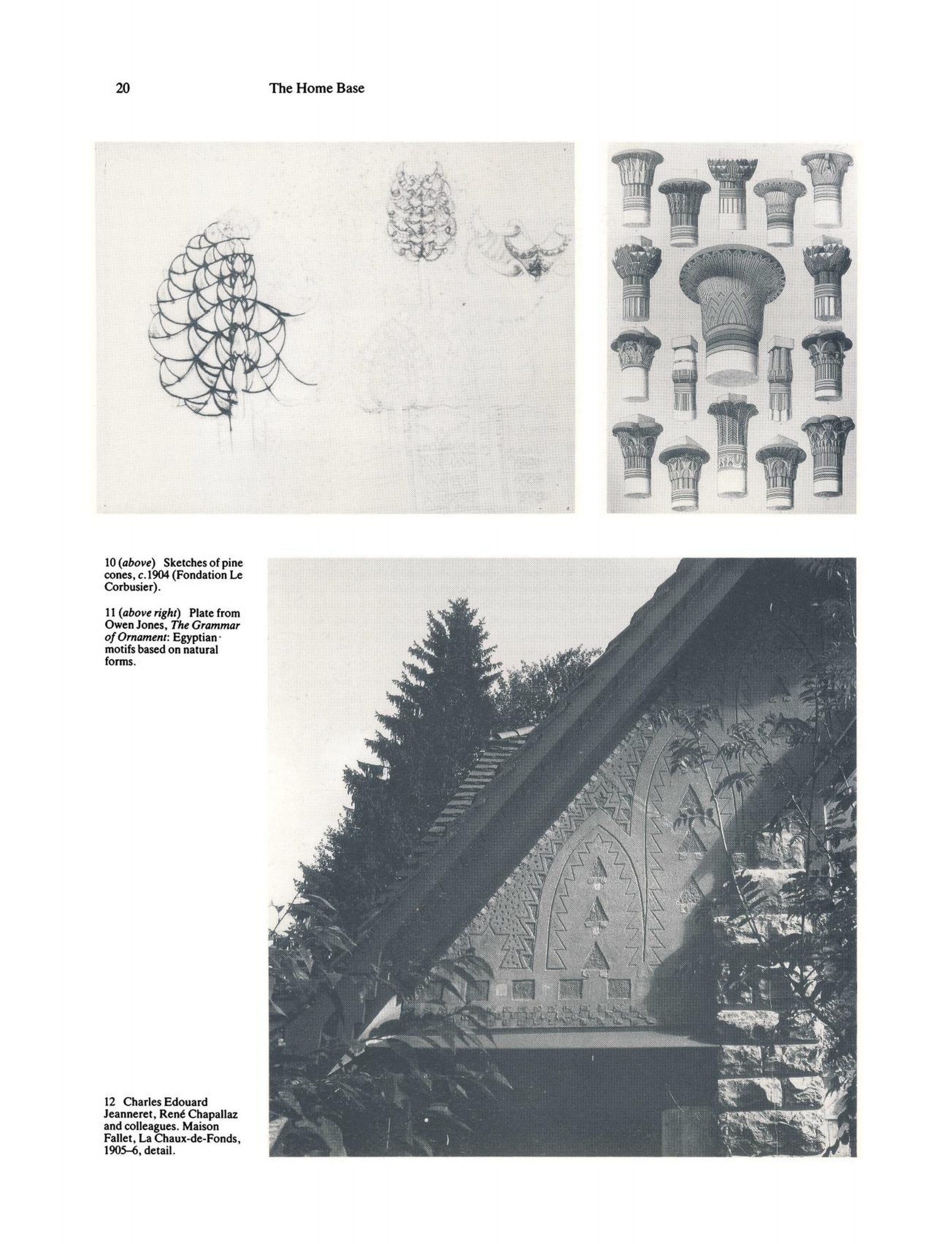

Throughout his career Le Corbusier tried incessantly to anchor symbols appropriate to his age and its techniques, in the kind of ‘fundamental’ order that he had sensed in nature and in the great works of tradition. We do well to take him seriously when he declares that history was his ‘only real master’. He looked for common themes underlying past buildings of different styles, and blended these together, transforming them to his own purposes. He sketched heroic and humble buildings in order to extract some essential or remarkable feature, then let impressions soak in his memory, from which ideas might emerge years later having undergone a ‘sea change’. He tried to abstract principles from tradition, and to distil these into a formal system with its own rules of appropriateness.

Before entering a world of such imaginative richness, we do well to leave aside simplistic theories concerning the genesis of forms. Part of the tension of Le Corbusier’s art stems from its fusion of paradoxes and polarities. A utopian with one eye on the future, he turned to the past for inspiration; a rationalist and lover of systems of classification, he experienced the world mythopoeically in all its uniqueness; an individualist, he tried to contain the anarchic forces of modern technology in what he piously hoped were ‘unchanging’ and natural laws; an internationalist, he remained sensitive to regional differences. Polarities of theme were sometimes reflected in contrasts of a form, which brought a rich ambiguity to even the most apparently simple designs. He was the supreme formal dialectician, placing rectangular against curved, open against closed, centric against linear, plane against volume, mass against transparency, grid against object, object against setting. His forms were a blend of sensual and abstract, material and spiritual, enthusiastic and ironical. In all this he learned from Cubism, not only for its plastic language, but also for the topsy-turvy order it gave to the world.

Like many other artists born in the late nineteenth century, Le Corbusier regarded himself as something of a prophet, revealing the ‘essence of the times’ to his fellows. Historicist, progressive and idealistic patterns of thought were embedded in his outlook; they were intrinsic to the very idea of ‘modern’ architecture. Le Corbusier rejected facile revivalism and materialist functionalism. He saw architecture in lofty, even spiritual terms. He grappled with age-old human and artistic questions, invoking what Wright called ‘that law and order inherent in all great architecture’. He realized that the best in the new must touch the best in the old. He was a traditionalist as well as a modernist, who felt that a purification of architecture in terms of his own time might also take it back to its roots.

The role of ‘modern master’ cast for Le Corbusier by early historians of modern architecture never did justice to the formal and metaphorical complexity of his work. It excluded vast areas of his historical imagination, his regionalist and classicizing formative works, the primitivism of his middle years, and the ideological contradictions of his urbanism. Even the ‘white architecture’ of the 1920s (much of it actually polychrome!) suffered from being lumped together under that questionable heading ‘International Style’. To present the myth of a unified style of the times it was necessary to confound Le Corbusier’s lyrical villas with many lesser creations that obediently wore the period uniform of boxes on stilts and strip windows. The demonologies of current post-modernist folklore also revert to stereotypes: modern architecture sinned (we learn) by rejecting the past, meaning, culture, for an arid world of rootless functionalism. The works of the modern masters are lumped together with any old glass box without discrimination. Happily scholarship does not have to follow architectural fashion. The cramped categories of modernist and post-modernist rhetoric fail to touch what is really interesting about architects like Frank Lloyd Wright, Mies van der Rohe, Alvar Aalto, Louis Kahn and, of course, Le Corbusier.

Not that one is recommending a Corbusian academy. Enough of these have existed already, with their trite tricks and cultish practices. If Le Corbusier has lessons for the future they are probably not in the imitation of externals of his style, but rather in emulation of his principles and processes of transformation. Even if one decides that Le Corbusier’s analyses of the modern condition are no longer relevant (and this is debatable), his work begins to settle into history as a major contribution. Architecture of any profundity outlives the culture, conflicts and conventions that brought it into being. Surely there is a quality in any artist of stature which transcends merely period concerns to link up with fundamentals of the medium. It is what Le Corbusier was himself talking about when he wrote in Vers une architecture: ‘Architecture has nothing to do with the various styles’.

The historian who sets out to touch on these timeless levels in Le Corbusier draws on the collected insights of the past decades, and especially (I think) on the interpretations of Stanislaus Von Moos, Peter Serenyi, Reyner Banham, Colin Rowe and Alan Colquhoun. I have included specifically scholarly acknowledgements in text, notes and bibliography, but I also wish to single out Eduard Sekler and Denys Lasdun, the former for showing me (a decade and a half ago) that Le Corbusier was an architect deserving the most careful art-historical scrutiny, the latter for sharing over many years his understanding of a master who played a major part in his own formation. I have also gained from conversations with Timothy Benton, Pat Sekler, Jerzy Soltan, Paul Turner, Roggio Andréini, Charles Correa and P.L. Varma. Finally I would like to thank Madame Frey of the Bibliothèque de la Ville, La Chaux-de-Fonds, and the Fondation Le Corbusier for their co-operation, and Phaidon Press (especially Bernard Dod) for doing the usual fine job.

Le Corbusier entered my imagination long before I had ever heard of something called ‘art history’. I came across the Oeuvre complète in the school library at the age of fifteen and was immediately captivated by this curious world of white villas and huge black cars, of concrete scoops and wiry pen and ink doodles. I hitchhiked to see the real thing for myself. Le Corbusier’s buildings seemed then (and still seem now) haunting yet secretive. They elude glib categories and have a silent life of their own. I shall be quite content if I have succeeded in this book in presenting what is so far known in a clear form, and adding a few fresh insights. You cannot be ‘definitive’ about architects like this.

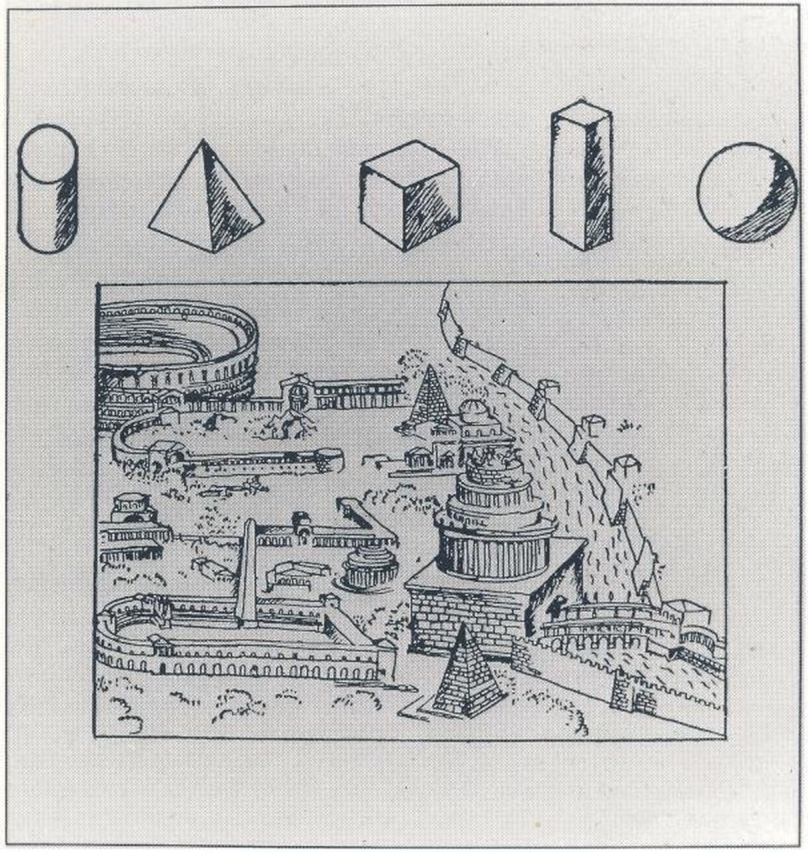

2. Sketch from Vers une architecture of primary solids and Ancient Rome:

the abstraction of principles from tradition.

This book was thought out in a rugged spot on the northern fringes of the Midi, with cypresses and vines visible through the window. It is the kind of landscape that the artist loved and often sketched, and I found this a good place to reflect on Le Corbusier’s debts to the ancient Mediterranean world. Nearly two-thirds of his buildings were within a few hours’ drive and I visited them often. The task of putting ideas straight was made more pleasant by the endless hospitality of Monsieur and Madame Raymond de Bournet, and through the constant encouragement of my wife, Catherine. She has accompanied my Corbusian quest through Indian dust, monks’ cells and Roman ruins: I dedicate this book to her.

William J.R. Curtis

Bournet, Ardèche, October 1985

CONTENTS

PREFACE 7

INTRODUCTION. Notes on Invention 11

PART I. THE FORMATIVE YEARS OF CHARLES EDOUARD JEANNERET 1887-1922

1 The Home Base 16

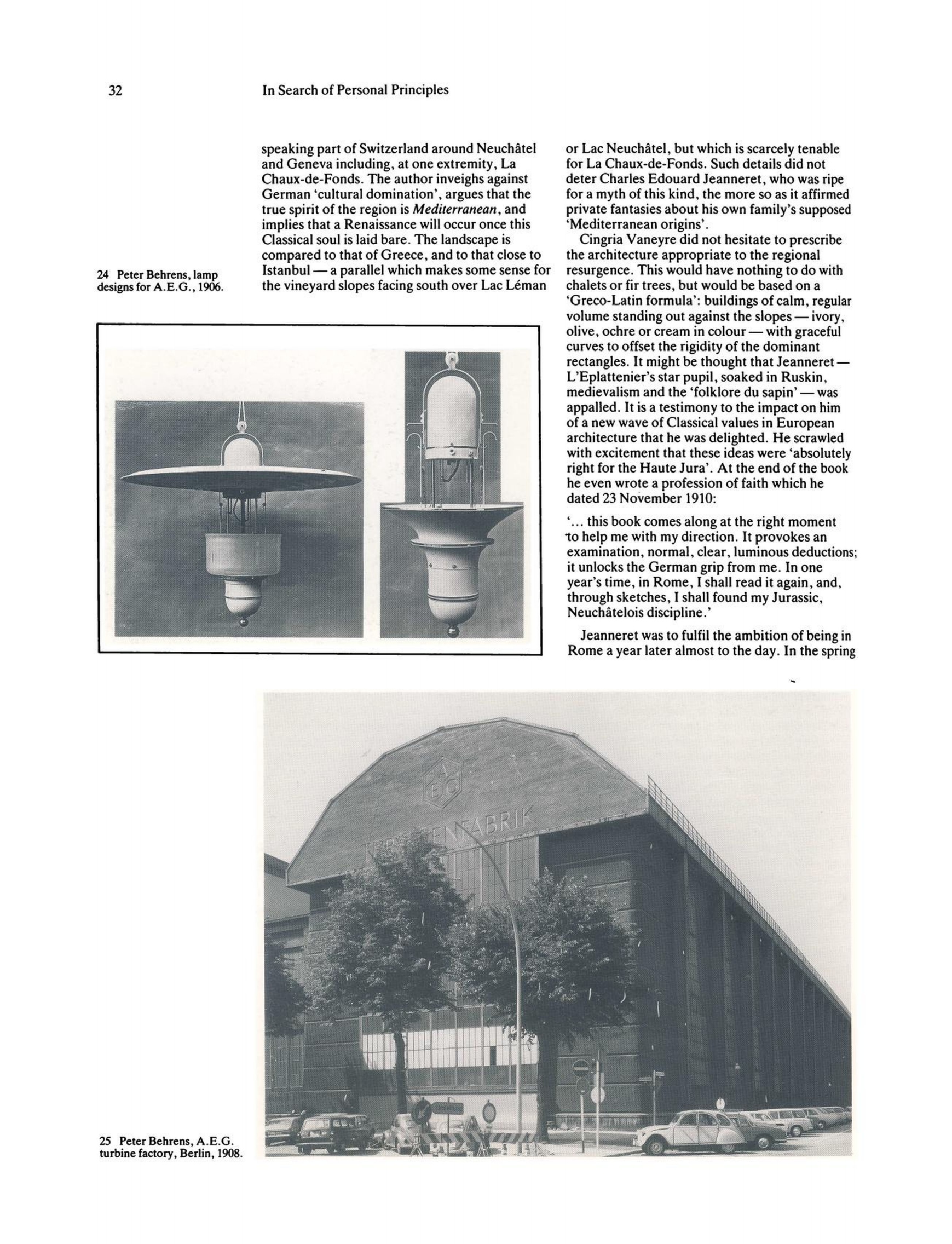

2 In Search of Personal Principles 26

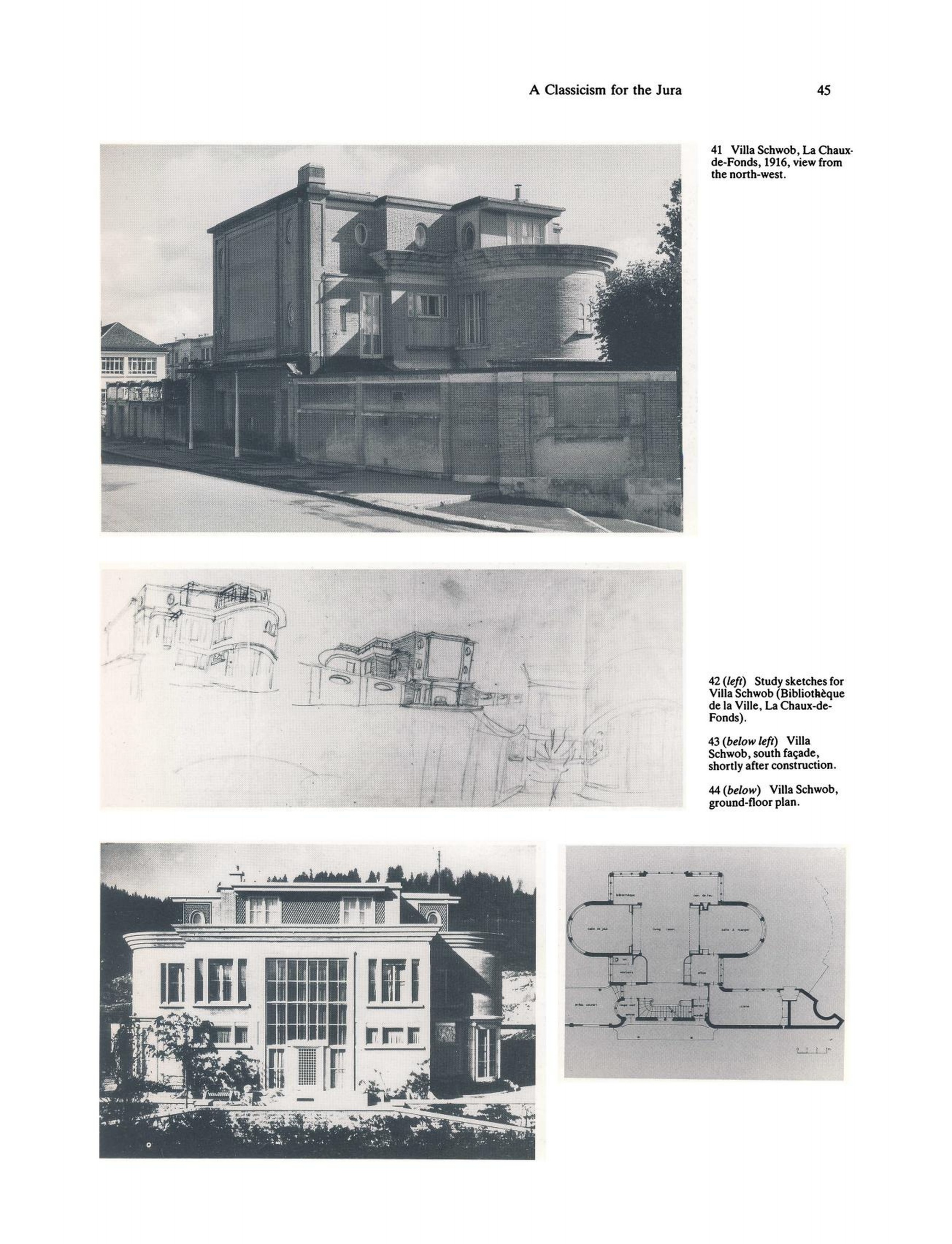

3 A Classicism for the Jura 37

4 Paris, Purism and ‘L’Esprit Nouveau’ 48

PART II. ARCHITECTURAL IDEALS AND SOCIAL REALITIES 1922-1944

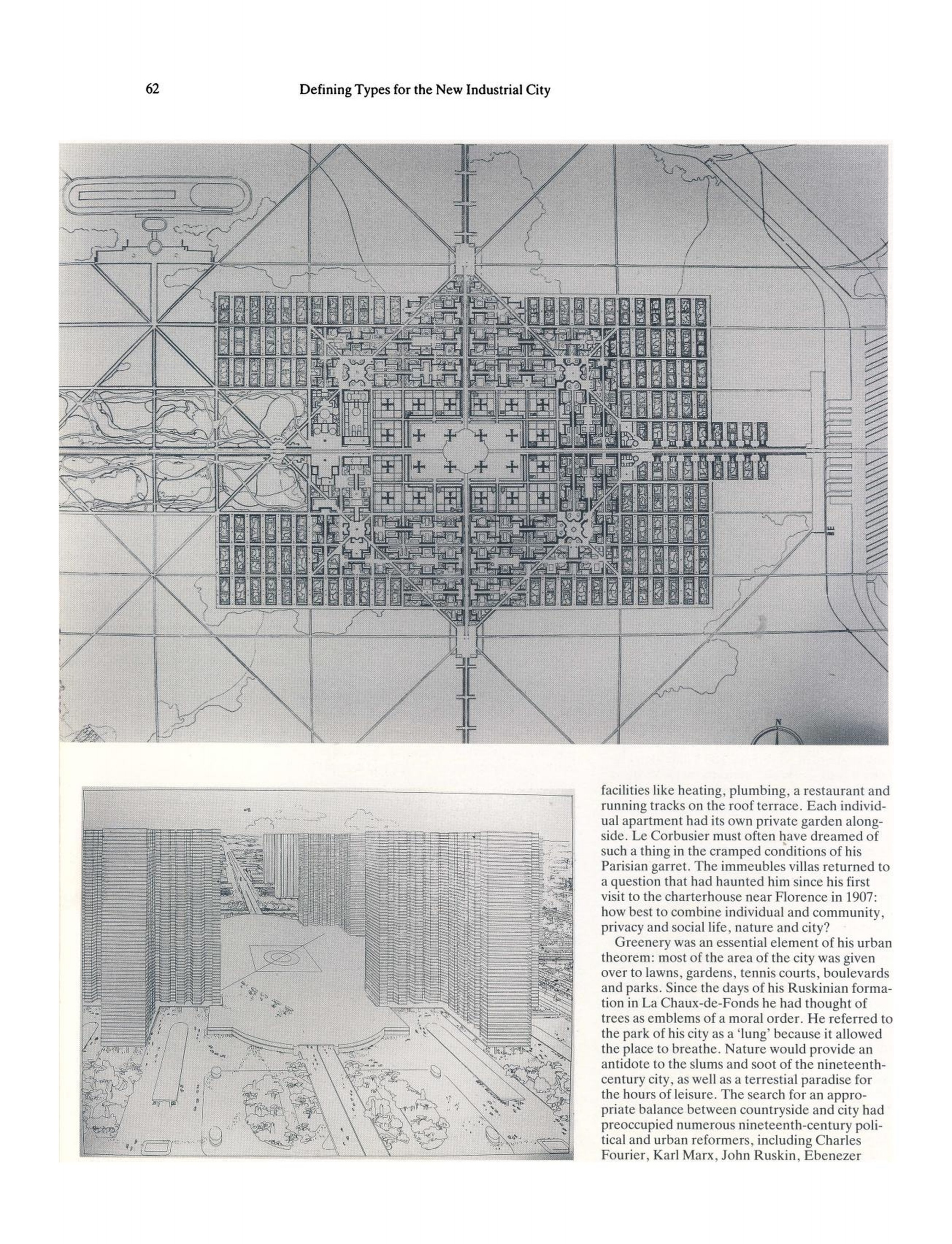

5 Defining Types for the New Industrial City 60

6 Houses, Studios and Villas 71

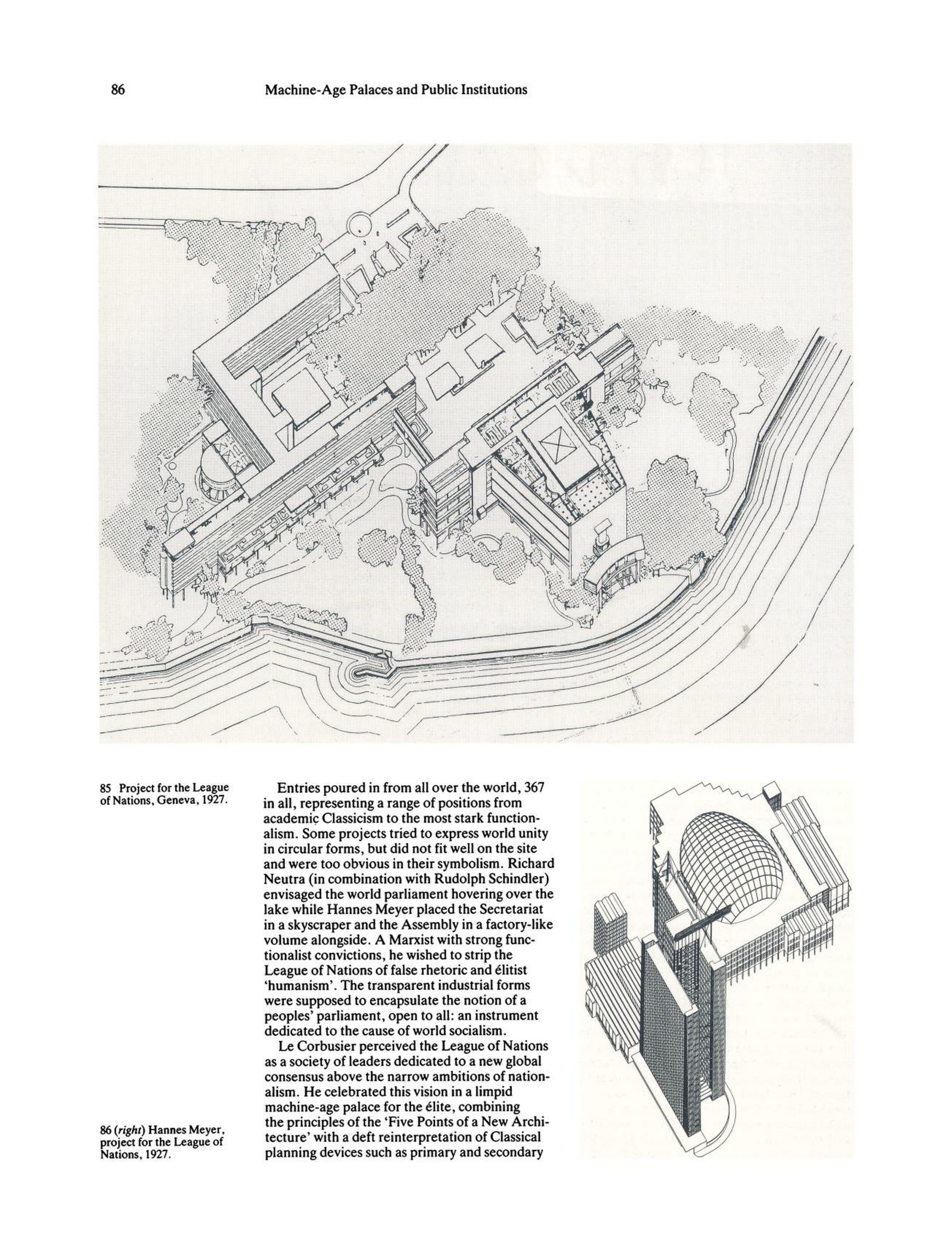

7 Machine-Age Palaces and Public Institutions 85

8 Villa Savoye, Cité de Refuge, Pavilion Suisse 93

9 Regionalism and Reassessment in the 1930s 108

10 Politics, Urbanism and Travels 1929-1944 118

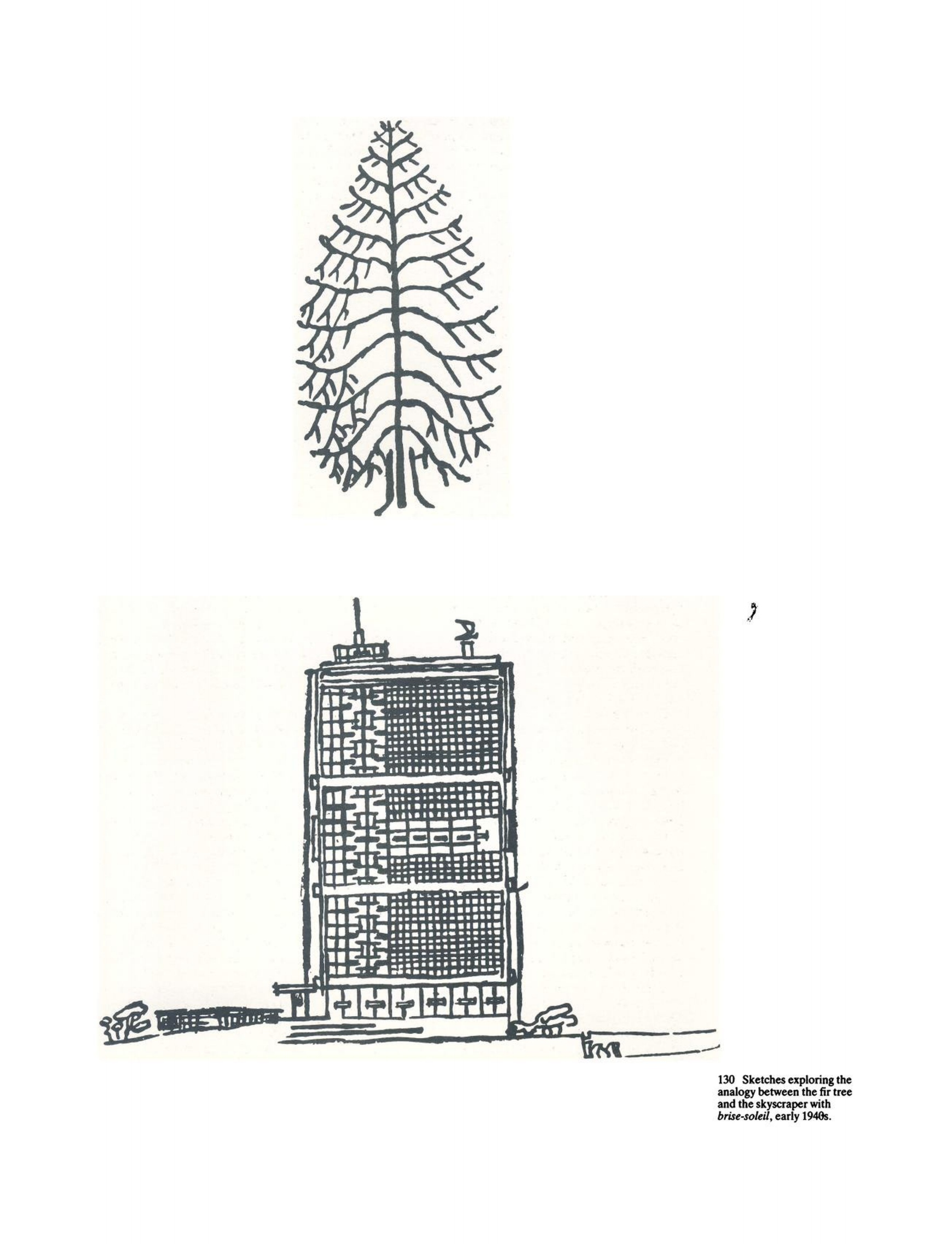

PART III. THE ANCIENT SENSE: LATE WORKS 1945-1965

11 The Modulor, Marseilles and the Mediterranean Myth 162

12 Sacral Forms, Ancient Associations 175

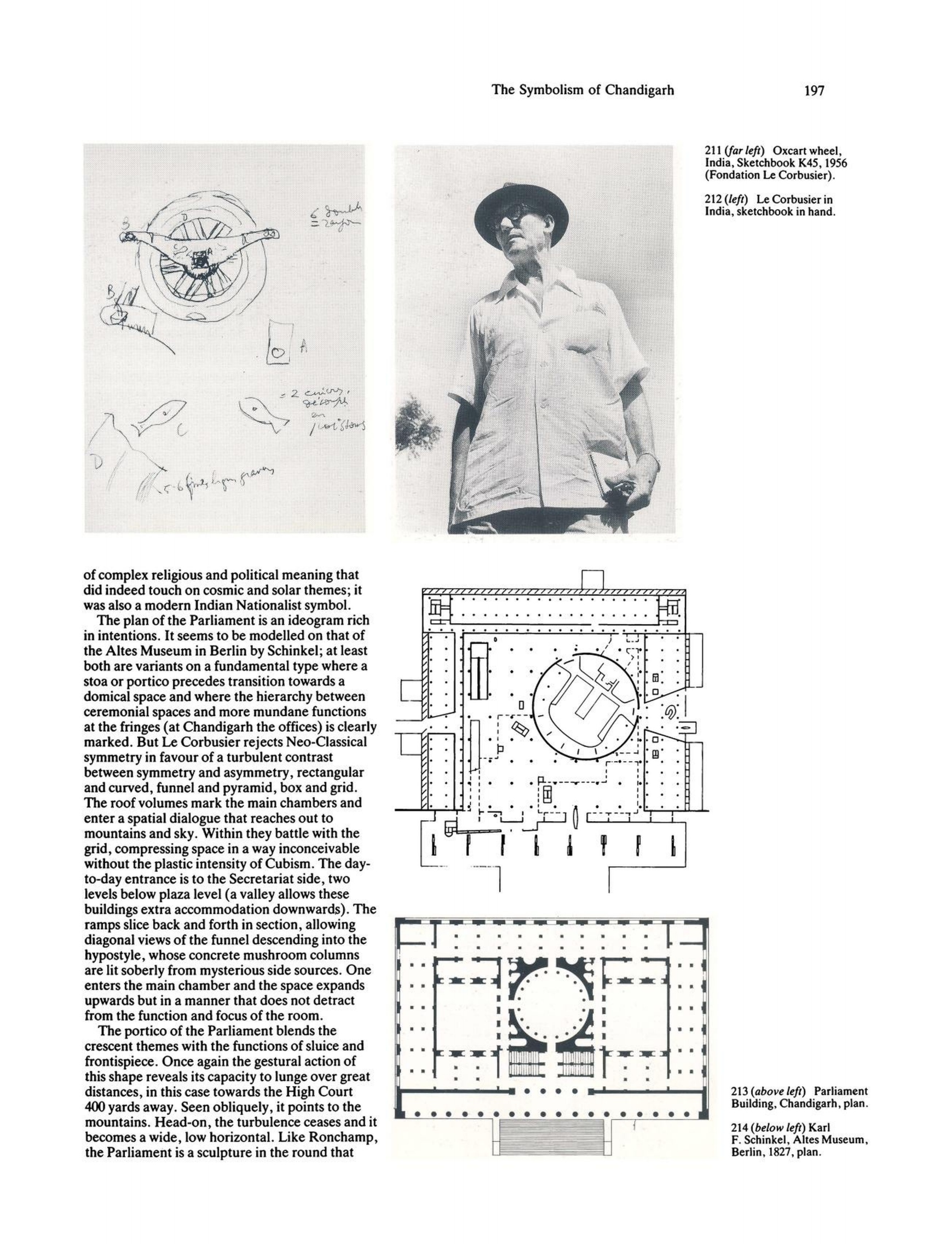

13 Le Corbusier in India: The Symbolism of Chandigarh 188

14 The Merchants of Ahmedabad 202

15 Retrospection and Invention: Final Projects 213

CONCLUSION Le Corbusier: Principles and Transformations 223

BIBLIOGRAPHY AND NOTES 230

INDEX 237

Примеры страниц

Скачать издание в формате pdf (яндексдиск; 253 МБ).

Все авторские права на данный материал сохраняются за правообладателем. Электронная версия публикуется исключительно для использования в информационных, научных, учебных или культурных целях. Любое коммерческое использование запрещено. В случае возникновения вопросов в сфере авторских прав пишите по адресу 42@tehne.com.

18 апреля 2017, 20:38

0 комментариев

|

Партнёры

|