|

|

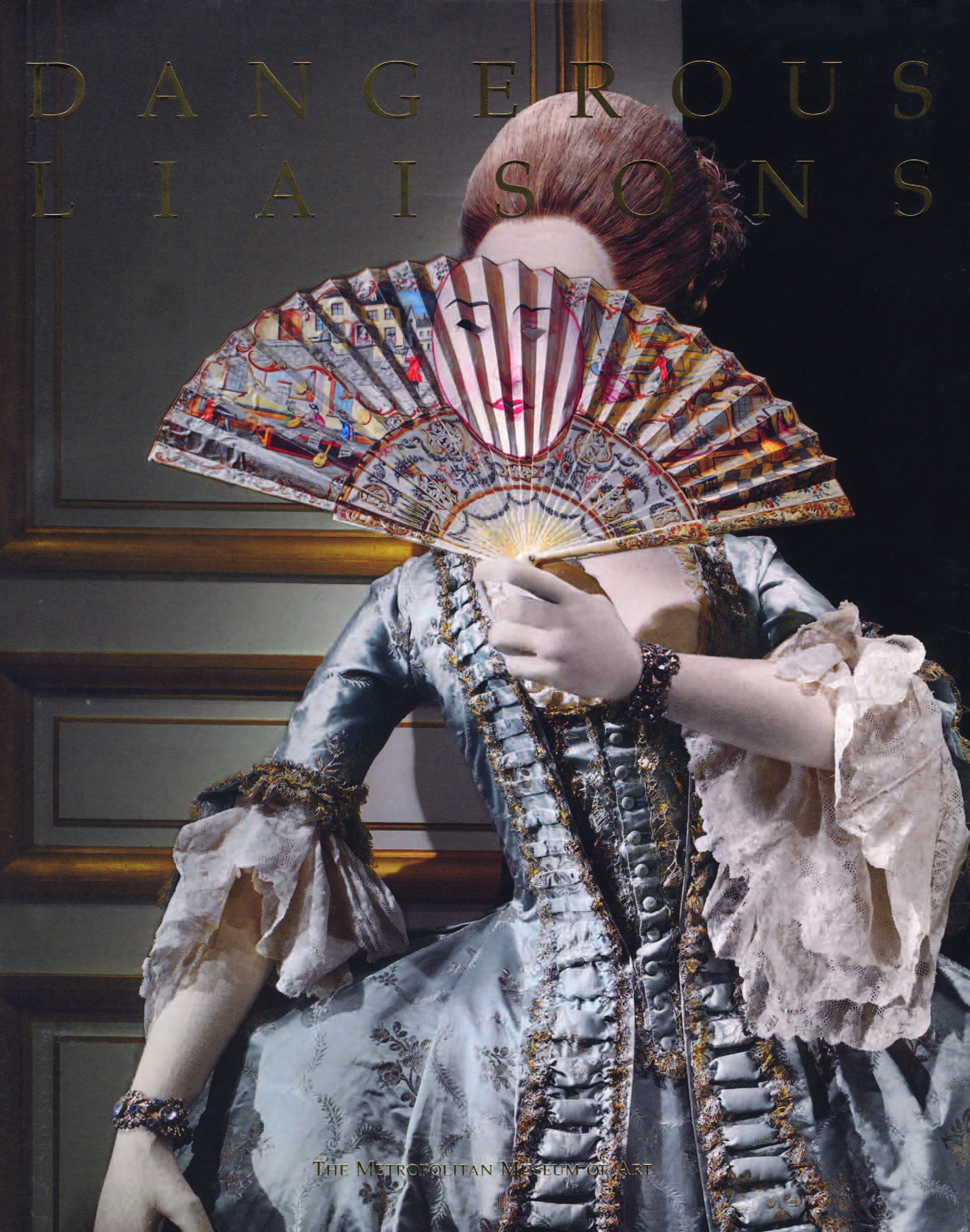

Dangerous Liaisons: Fashion and Furniture in the Eighteenth Century. — New York, 2006  Dangerous Liaisons: Fashion and Furniture in the Eighteenth Century / Harold Koda and Andrew Bolton ; With an introduction by Mimi Hellman. — New York : The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2006. — 128 p., ill. — ISBN 1-58839-147-7

During the reigns of Louis XV (1723–74) and Louis XVI (1774–92) fashion and furniture merged ideals of beauty and pleasure through their forms and embellishments. With their fragile surfaces and delicate proportions, tables, chairs, and other pieces of furniture enhanced the elite's indulgence in leisurely pursuits, fostering highly complex standards of etiquette and performance. Men and women restated the splendor of the Rococo and Neoclassical interiors of the period in their opulent costumes. For the eighteenth-century libertine and femme du monde, a refined elegance and delicate voluptuousness infused their world with a mood of amorous delight.

Dangerous Liaisons takes its theme from this era, when trifling in love propelled the energies of elite men and women, providing almost daily stimulating encounters, and when, as has been written, "morality lost but society gained." In Choderlos de Laclos's novel of the same name, Cécile, a young girl, is praised by her tutor in the worldly arts: "She is really delightful! She has neither character nor principles ... everything about her indicates the keenest sensations." Valmont, her seducer, notes the following morning, "Nothing could have been more amusing." Valmont has won a game in the contest of lovemaking.

The beautifully photographed and handsomely reproduced images on the following pages bring these amorous adventures to life. The vignettes, staged for the widely praised exhibition "Dangerous Liaisons: Fashion and Furniture in the Eighteenth Century," held at The Metropolitan Museum of Art in 2004, feature eighteenth-century costumes in the Museum's spectacular French period rooms, The Wrightsman Galleries. The artfully composed scenes include: a woman sitting for her portrait while her husband flirts with her friend; a man being granted an audience with a woman in a peignoir who is having her hair dressed; a vendor embracing the wife of an old man, his back turned, examining a table for sale; a girl receiving more than a harp lesson from her teacher, while her oblivious chaperone reads an erotic novel; a woman giving up her garter as a memento of a very private dinner. The entertaining and knowledgeable texts set the scenes perfectly.

Foreword

In 1963 figures dressed in the attire of Louis XV and Louis XVI were placed in informal vignettes throughout the Museum's French period rooms, The Wrightsman Galleries. Since then, the rooms have benefited from a series of new acquisitions and gifts, many with exceptionally distinguished provenances, and all displaying the most refined artistry of the period. After more than four decades, "Dangerous Liaisons: Fashion and Furniture in the 18th Century" restated the strategy of that earlier installation, now greatly enhanced by the many additions to the rooms.

For the Metropolitan, the collaboration of our departments of European Sculpture and Decorative Arts and The Costume Institute is an important reflection of the collegiality and diversity of our curatorial expertise and the breadth of our holdings. This Museum is especially well-positioned for such interdepartmental "synergies." However, the narratives that linked the rooms in "Dangerous Liaisons" were a kind of theater, and unusual for an art museum. More typically, artworks are displayed with the understanding that their aesthetic merit and the virtuosity of their creators are better conveyed when they are separated spatially to underscore their uniqueness. Unlike natural-history dioramas or historical-society tableaux, presentation of works in an art museum is generally without recreation of their original social and cultural contexts.

Perhaps no one was more surprised than the contributing curators to see how the exceptional nature of their objects was enriched by such juxtapositions. To view the elaborately attired figures in the rooms was to understand the just proportions of the spaces. Such settings also served to link and unify the rarefied opulence of the furniture and costumes. Moreover, through these vignettes eighteenth-century conceits and social behavior were made more accessible and human because of the intimacy implicit in the playful narratives.

"Dangerous Liaisons" would not have been possible without its unparalleled settings and the masterworks assembled there by Jayne Wrightsman, whose generosity, knowledge, and insight have informed the evolution of the Museum's collection of eighteenth-century furniture and decorative arts. Most of the fine examples of eighteenth-century dress came from the superlative holdings of The Costume Institute, which were enhanced by rare works from the collections of Lillian Williams and the Kyoto Costume Institute.

"Dangerous Liaisons" was organized by Harold Koda, curator in charge of The Costume Institute, and Andrew Bolton, associate curator, who, along with Mimi Heilman, assistant professor of art history at Skidmore College, are the authors of this book adapted from the exhibition. Beautifully conceptualized and staged by Patrick Kinmonth and expertly photographed by Joseph Coscia Jr. and Oi-Cheong Lee, the vignettes that follow will certainly transport the reader back to this "age of allurement."

We are extremely grateful to Asprey for their generous support of both the exhibition and this book. We would also like to thank Condé Nast for their additional support of both projects.

Philippe de Montebello

Director, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Preface

The exhibition "Dangerous Liaisons: Fashion and Furniture in the 18th Century," from which this book is derived, is the second instance of costume presented in The Wrightsman Galleries. While the first, "Costumes: Period Rooms Re-occupied in Style" (1963), also featured notable examples of eighteenth-century dress, they were presented in tableaux of neutral, sparely articulated narratives. Emphasis was placed on the clothing rather than the furniture and architectural components. For "Dangerous Liaisons," however, the curators elected a different approach, one intended to establish a more dynamic occupation of the rooms. Through a series of dramatic vignettes, equal prominence has been given to the apparel and the applied arts.

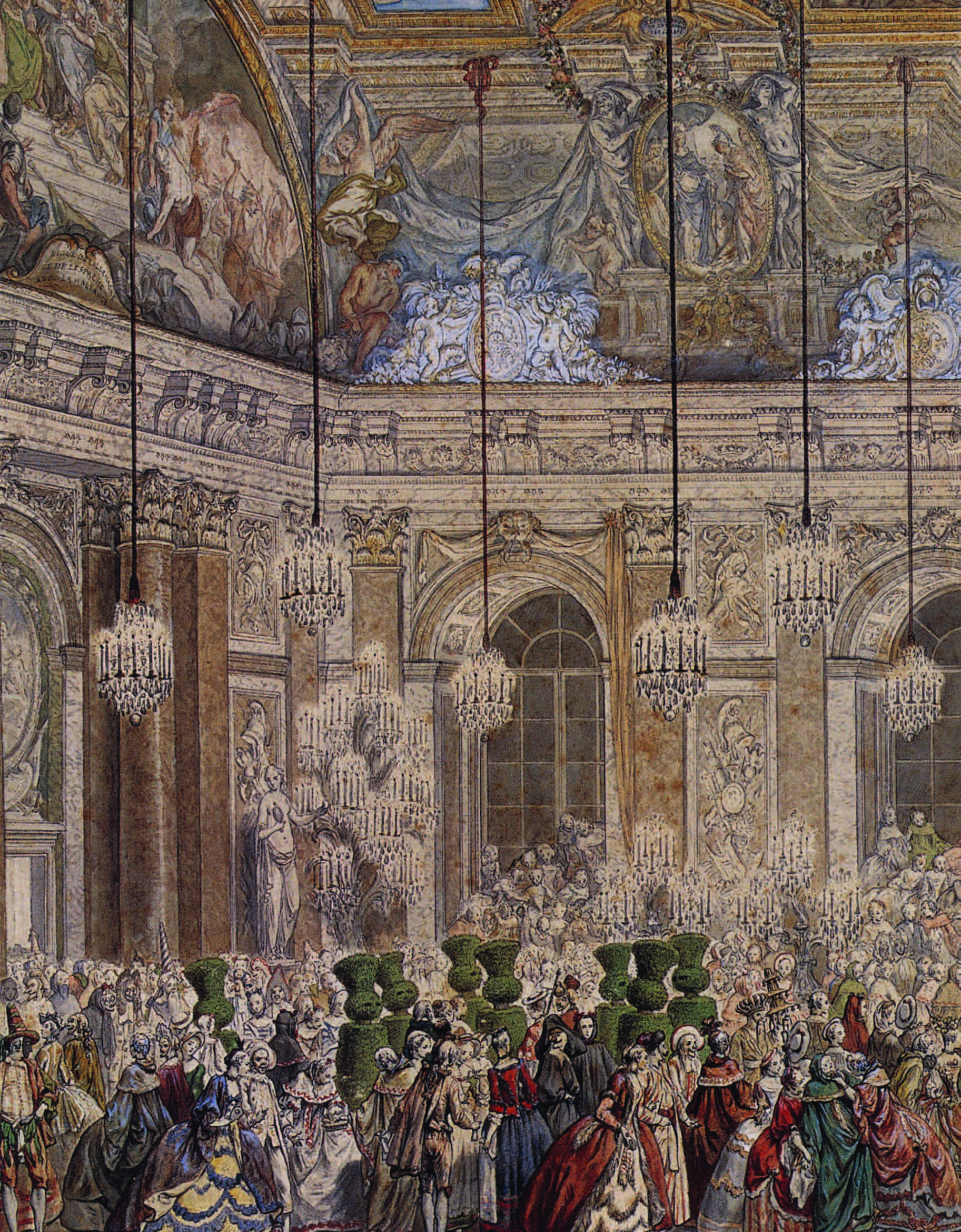

Philippe de Montebello has noted that the Metropolitan's period rooms, including The Wrightsman Galleries, "were installed principally ... to display suites of furniture selected from the Museum's holdings and combined in the setting to express a particular style, rather than to reinvent the original room." With similar intentions, the curators of "Dangerous Liaisons," along with the exhibition's creative director, Patrick Kinmonth, staged tableaux that effected a stylistic relationship between fashion and furniture in the eighteenth century. The scenes allude to the carefully cultivated appearances and accomplished behaviors in codified rituals that characterized the social activities of the French nobility of the period. To further emphasize the artifice and theatrical nature of the scenarios, Kinmonth introduced footlights to the existing diffuse daylight and candlelight effects of the rooms, resulting in an "up-lit" effect of a Watteau painting. For all its dramatic invention, however, the premise of the exhibition was to establish an apparent discourse between objects. In every room furniture remained as originally placed or was only slightly shifted to accommodate the mannequins. The actions of the figures were, therefore, directly predicated on concepts originating from the rooms and the décor.

Eighteenth-century prints, drawings, and paintings documenting the insouciant life of the ancien régime elite served as inspiration for the vignettes, as did popular libertine literature of the period. In particular, the curators were reliant on two works for establishing the exhibition's narrative parameters. The first, Jean-François Bastide's novella La Petite Maison (1758), linked architecture and decorative arts to stratagems of seduction, while the second, Jean-Michel Moreau le Jeune's compilation of engravings, Monument du costume (1789), described aristocratic diversions with idealized "day-in-the-life-of" detail.

La Petite Maison is, as the architectural scholar Rodolphe El-Khoury has written, "an intersection of the libertine novel and critical commentary on architecture." For Bastide's hero, the Marquis de Trémicour, a worldly counterpart to the better-known Vicomte de Valmont in Choderlos de Laclos's Les Liaisons dangereuses (1782), the sumptuous aesthetic of eighteenth-century French design is less simple scenography than an active accomplice in his amorous pursuits. For example, a particularly challenging interlude for Mélite, the elusive subject of the marquis's attentions, occurs when she is led into an ingeniously decorated round salon, similar spatially to the Museum's own Bordeaux Room (p. 99). Anthropomorphism insinuates itself when the salon emerges as a third party, and, in effect, as a seducer even more compelling than (though in the service of) the ardent marquis. In the world of de Trémicour and Mélite, erotic games are played out by extravagantly dressed elites in homes of luxurious refinement.

While the dress of the two protagonists is not described, de Trémicour would have worn a sleekly fitted silk suit embellished with lace jabot and cuffs, while Mélite was probably attired in a robe à la française of the type seen on page 49. Her natural silhouette would have been exaggerated by her corset and panniers, the one constraining her body as the other amplified its effect. The finely embellished, elaborately brocaded silk comprising her dress would have been arranged to display the finer points of her exposed nape and bust. At the same time, it would have highlighted the grace with which she could negotiate its sheer volume, whether her full skirt through a doorway and around a delicately poised table or her lace cuffs, or engageantes, above a fragile tea service or a pot of rouge.

As Mimi Hellman describes in her essay, this interaction of the body with objects was a carefully choreographed, challenging exercise with important implications of status and social refinement. While in some instances in "Dangerous Liaisons" specific pieces of furniture inspired the telling actions of the figures, in others the rooms and their history precipitated the narratives. Because of the aesthetic unity that characterized the various arts presented, whether in terms of styles, motives, or technical accomplishments, fortuitous correspondences transpired. The transformative silhouette of an informal gown juxtaposed with a mechanical table, or the inflated hairstyle of a woman at her dressing table in a room with Jacob chairs with balloon finials, associate disparate phenomena into a legible gestalt.

In the exhibition Kinmonth referenced dressmaker's forms when he covered the mannequins with fine linen, an act that also recalled the interior finishes of eighteenth-century corsets. While clearly dummies, the figures were posed in naturalistic postures derived from period paintings and prints. The positioning of mannequins in attitudes of the eighteenth centuiy resulted in a convincing representation of elite decorum. For example, the female figures were not bent at the waist because a woman fitted with a corset and center-front busk was precluded from doing so. Instead, the eighteenth-century femme du monde was compelled to lean over with her back rigid, bending at her hips as in the case of the woman hovering over the prostrate figure in the Varengeville Room (p. 65). The wigs, made from hand-knotted human hair and designed by Campbell Young and his colleague, Chris Redman, introduced a particularly convincing visual effect, especially when they were powdered. A subtle detail seen in portraits of the period emerged more vividly when the powder drifted down to the roots and scalp, creating a delicate sfumato, lighter along the crown and hairline, and darker at the sides and back of the head. The exhibition's powdered coiffures balanced the lush luster and volume of the costumes of the day. With such attention to detail, the allure of the eighteenth-century woman was poetically evoked.

La Petite Maison concludes with Mélite emotionally overcome by the beauty of the décor in de Trémicour's house. While there was always the possibility that the placement of mannequins in the luxurious hauteur of The Wrightsman Galleries might fail to communicate the highly evolved sensibilities of the period, any doubts as to the validity of the project vanished when the figures began to be positioned in the rooms. With their opulent costumes, the mannequins humanized the scale of even the grandest space, and the narratives engaged the forms and design details of the Metropolitan's formidable masterworks of furniture and decorative arts with a compelling aesthetic unity. As demonstrated in the exhibition and in this lavishly illustrated publication, the exquisite art de vivre of eighteenth-century France, expressed through the dangerously seductive liaison of fashion and furniture, still has the power to please the mind and overwhelm the senses.

Contents

Sponsor's Statement.. 7

Foreword. Philippe de Montebello.. 9

Preface.. 11

Interior Motives: Seduction by Decoration in Eighteenth-Century France. Mimi Hellman.. 15

The Portrait: An Unexpected Entanglement.. 25

The Levée: The Assiduous Admirer.. 35

The Music Lesson: A Window of Opportunity.. 45

The Withdrawing Room: A Helpful Valet.. 59

The Masked Beauty.. 77

The Favorite.. 83

The Broken Vase: A Consoling Merchant.. 89

The Card Game: Cheating at Cavagnole.. 99

The Late Supper: The Memento.. 109

Catalogue.. 117

Illustrations.. 123

Select Bibliography.. 125

Acknowledgments.. 127

Sample pages

Download link (pdf, yandexdisk; 49,7 MB).

9 марта 2020, 19:45

0 комментариев

|

Партнёры

|