|

|

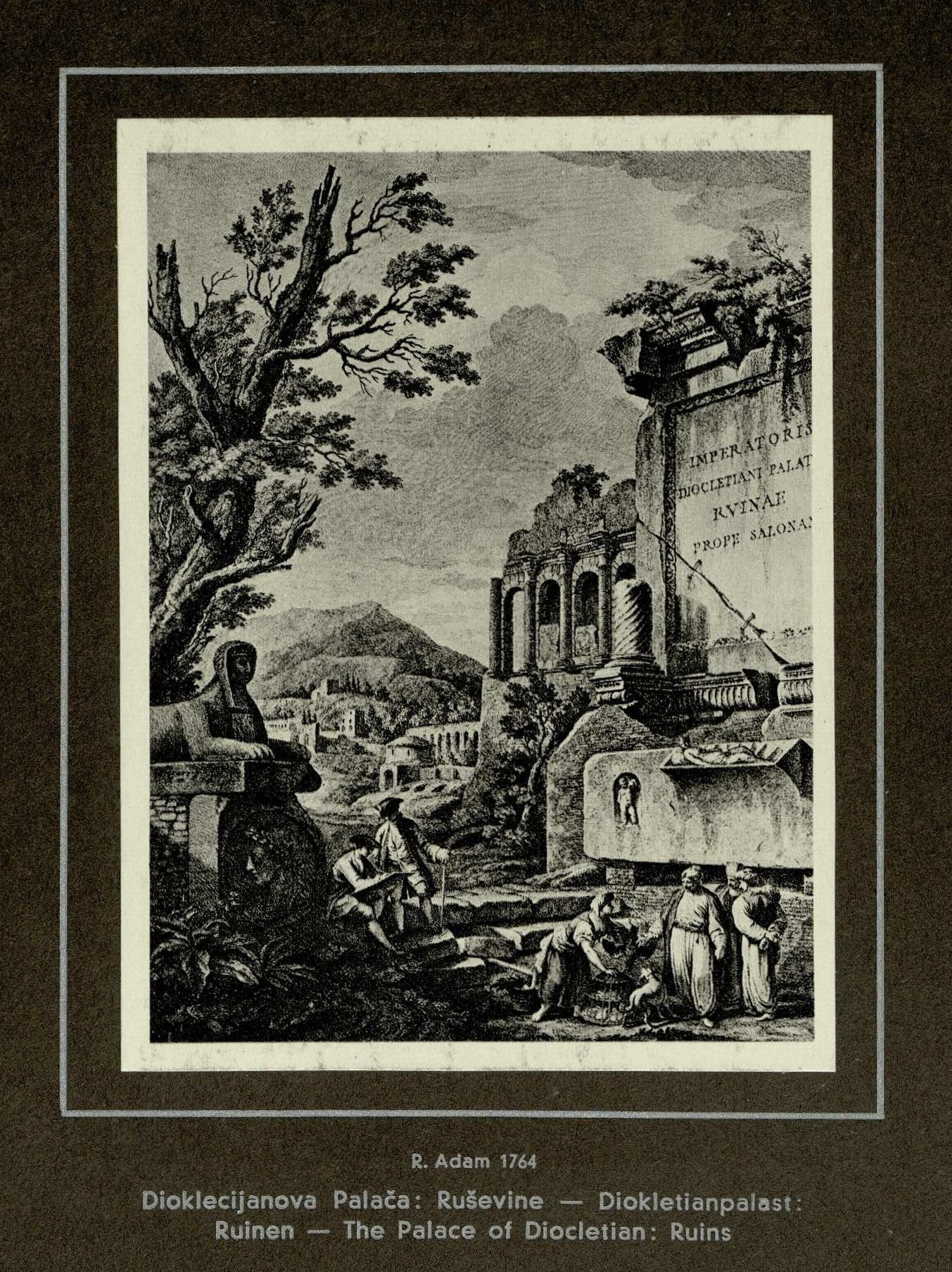

Dioklecijanova palača = The Palace of Diocletian = Palais de Diocletien = Diokletianpalast : Split – Jugoslavija. — Ljubljana, 1936Dioklecijanova palača = The Palace of Diocletian = Palais de Diocletien = Diokletianpalast : Split – Jugoslavija / Inž. Kamilo Tončić-Sorinjski. — Ljubljana : Jugoslovanska tiskarna, [1936]. — 16 p., 30 pl.Preface

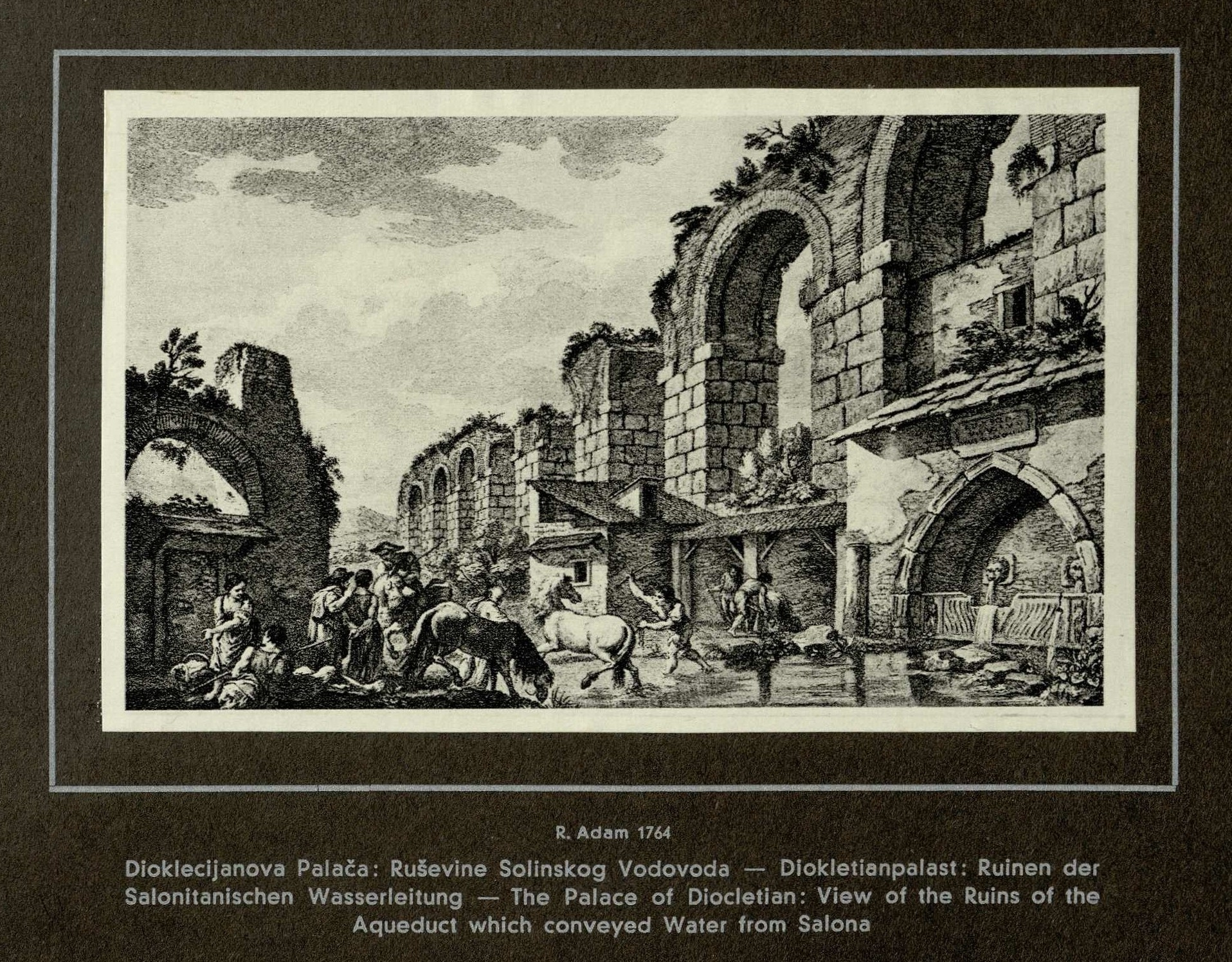

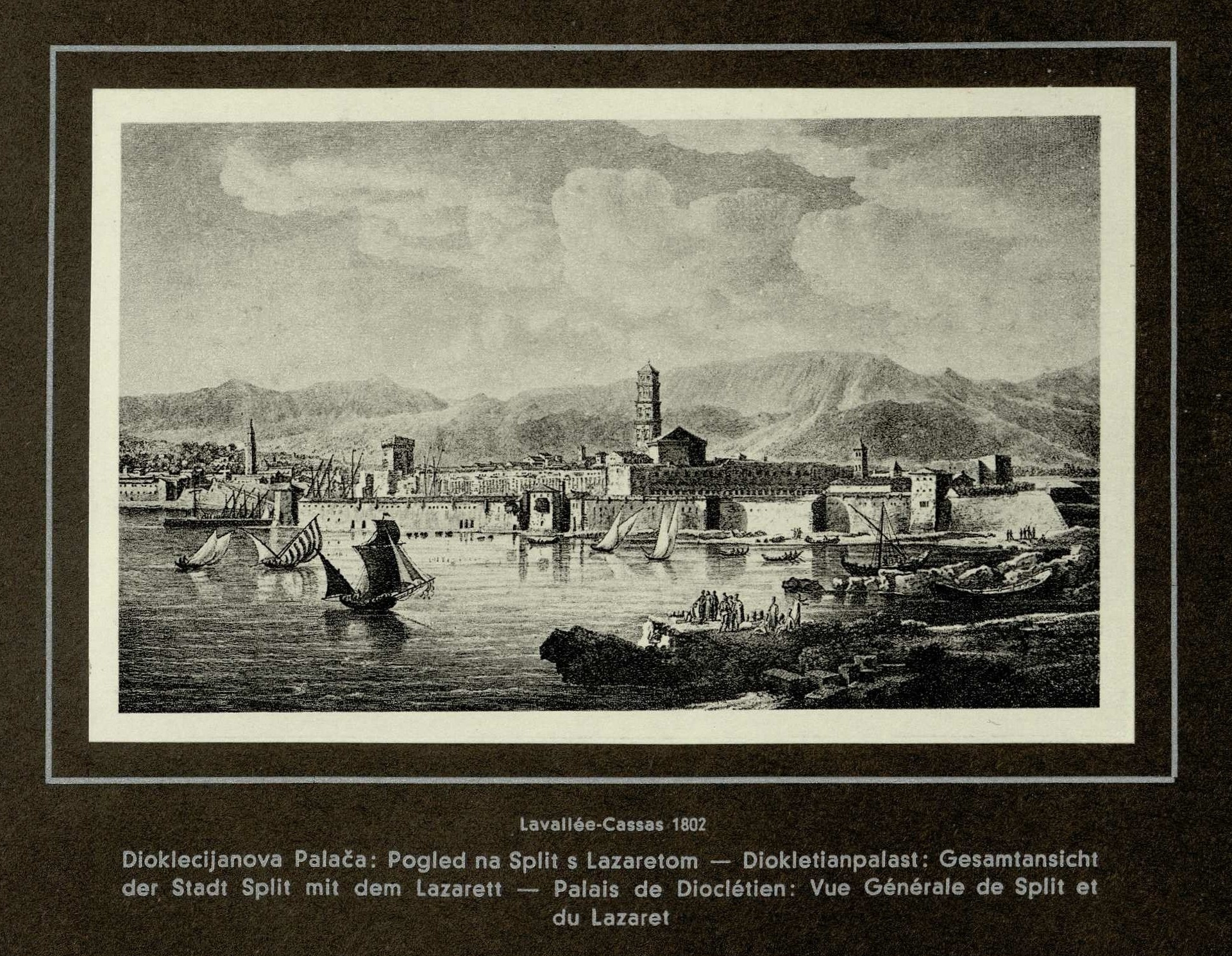

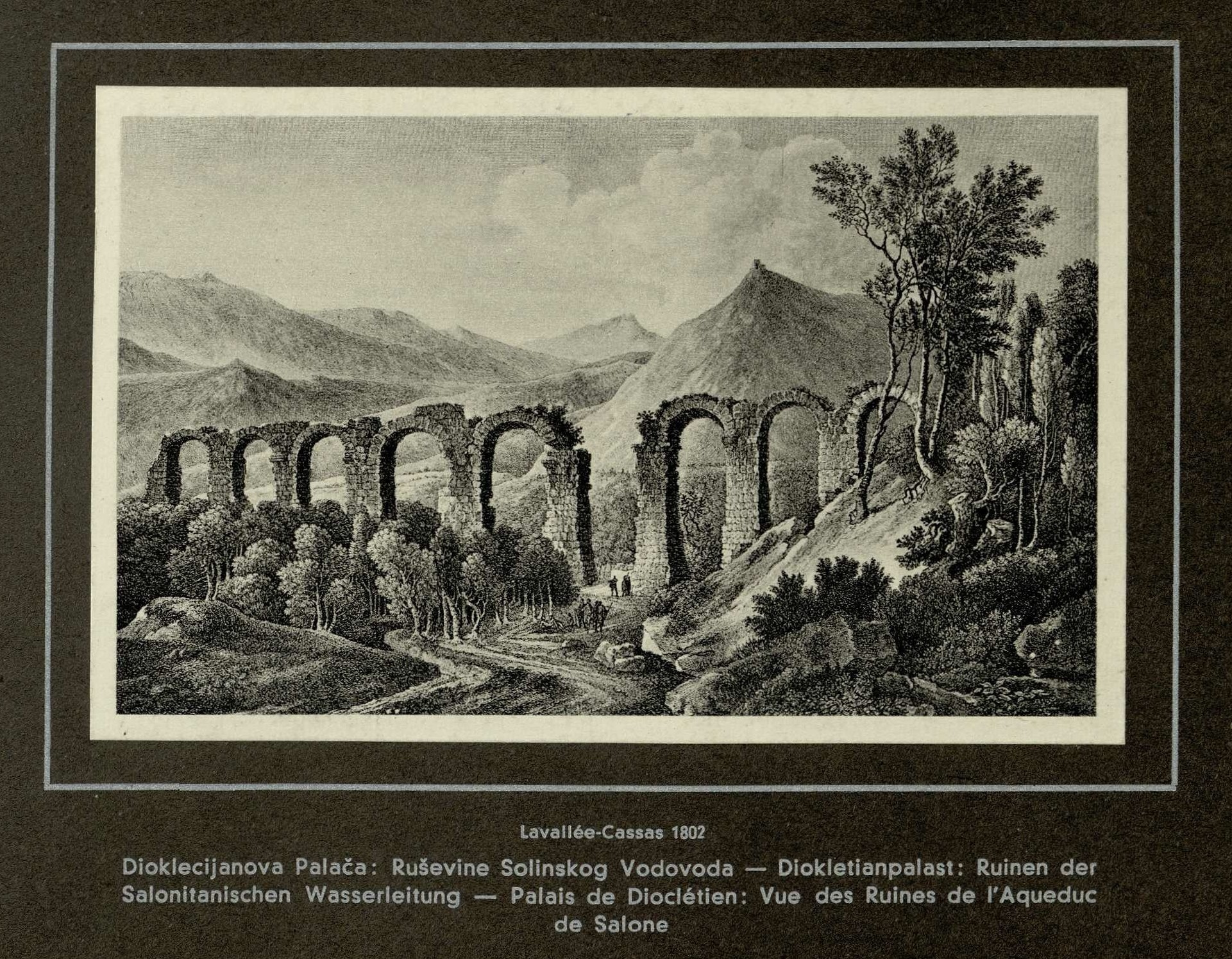

The Palace of Diocletian was erected in one of the most charming sites of the Dalmatian coast, three miles from the great Roman city of Salona, between the mountain once covered with woods and vineyards drawing at the horizon a vast amphitheater, and the sea sprinkled with islands and resembling to a blue and still lake. — Diocletian could hardly have chosen a place for his retreat with greater advantages than this.

This Palace was an immense and magnificent monument decorated with sumptuous buildings in dimensions of a town, a residence of the splendour the emperor took with him even in his retirement, one of the most precious performances of the antiquity.

More than six centuries after the death of its imperial owner it retained so much of its original magnificence that the imperial historian Constantine VII Porphyrogenet — »born in the purple« — himself and used to the semi-oriental state of Constantinople, declared that it surpassed even in its ruin all powers of description. — And even in its present state, ruined, defaced and overgrown with the mean accretions of sixteen centuries, its vast proportions and solid constructions excite our astonishment. Had Split no other claims to our attention, the mere name of Diocletian and his palace would be enough to make it exceedingly interesting. — »Split«, as the military governor of Napoleon in Dalmatia Marshal Marmont expresses himself, »seems to be like a divinity, the remains of which give us the highest idea of the Roman greatness. — What are we ourselves, the modern, after all, in comparison to such a power and similar grandeur?« Such stupendous workmanship is only for masters of the world: it has never been possible in any state of society since that of the Roman empire in the fourth century, and it can never be possible again!

It was built between 295 and 305 A. D. with an almost rectangular ground plan of a Roman camp — castrum. Originally it stood on the seashore but nowadays it is somewhat distant from it, and it measured on the western side 215 m, on the eastern 215.10 m, on the northern front 175.30 m, and on the southern 179.48 m. So it covered an area of about eight and a half acres or nearly 36.000 m2.

As the ground sloped upward from the shore towards the interior and the height of the enceinte was everywhere uniform, the walls were not so on all points of the ground: the southern walls (24 m) were higher than the northern ones (17 m). — It followed therefrom the possibility of installing a story more in the southern part than in the northern one.

The whole of this building was surrounded by fortified walls with a quadrangular tower at each of the four angles. The southwestern is gone in the sixteen centuries, and the other three are still in passable good preservation.

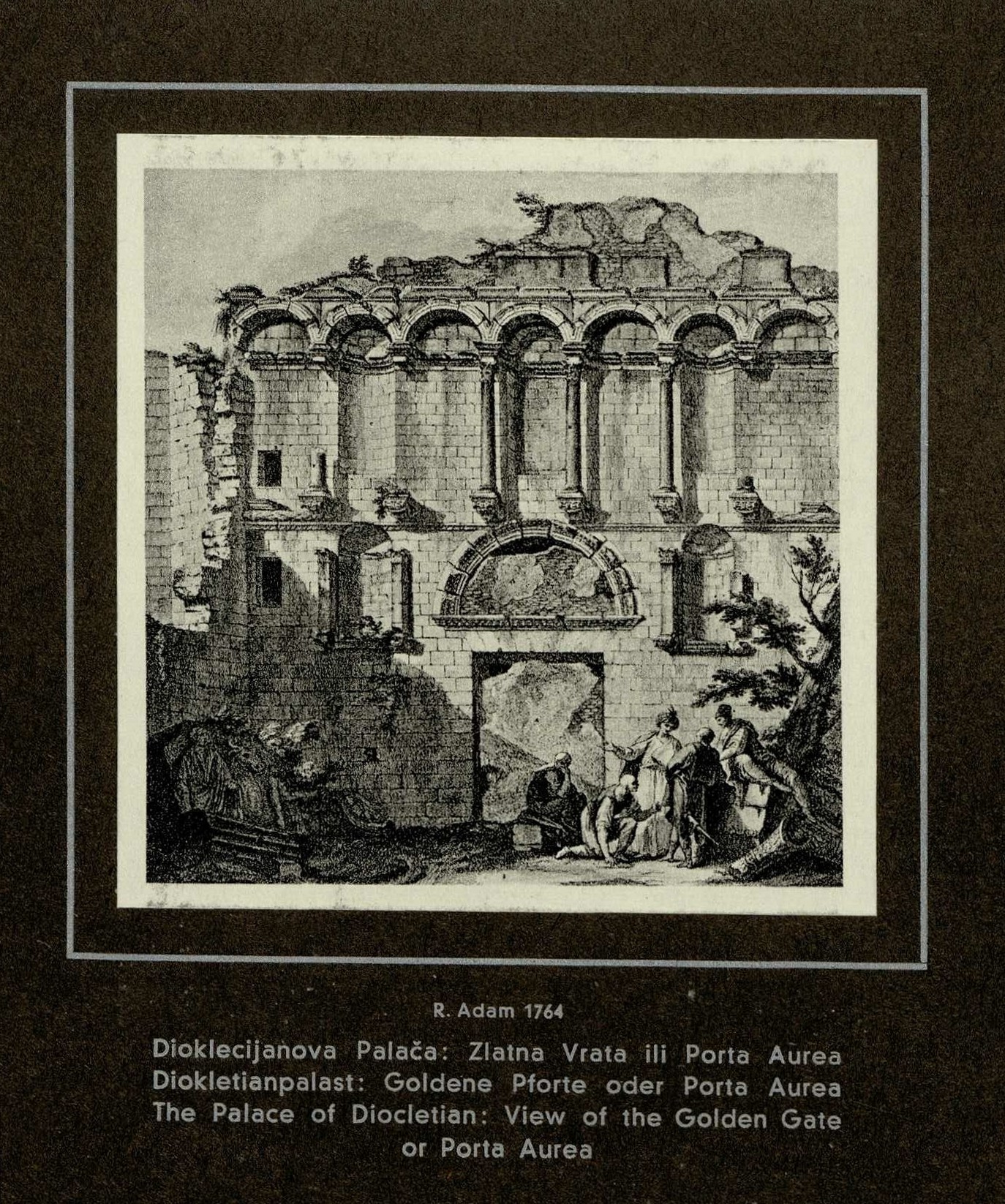

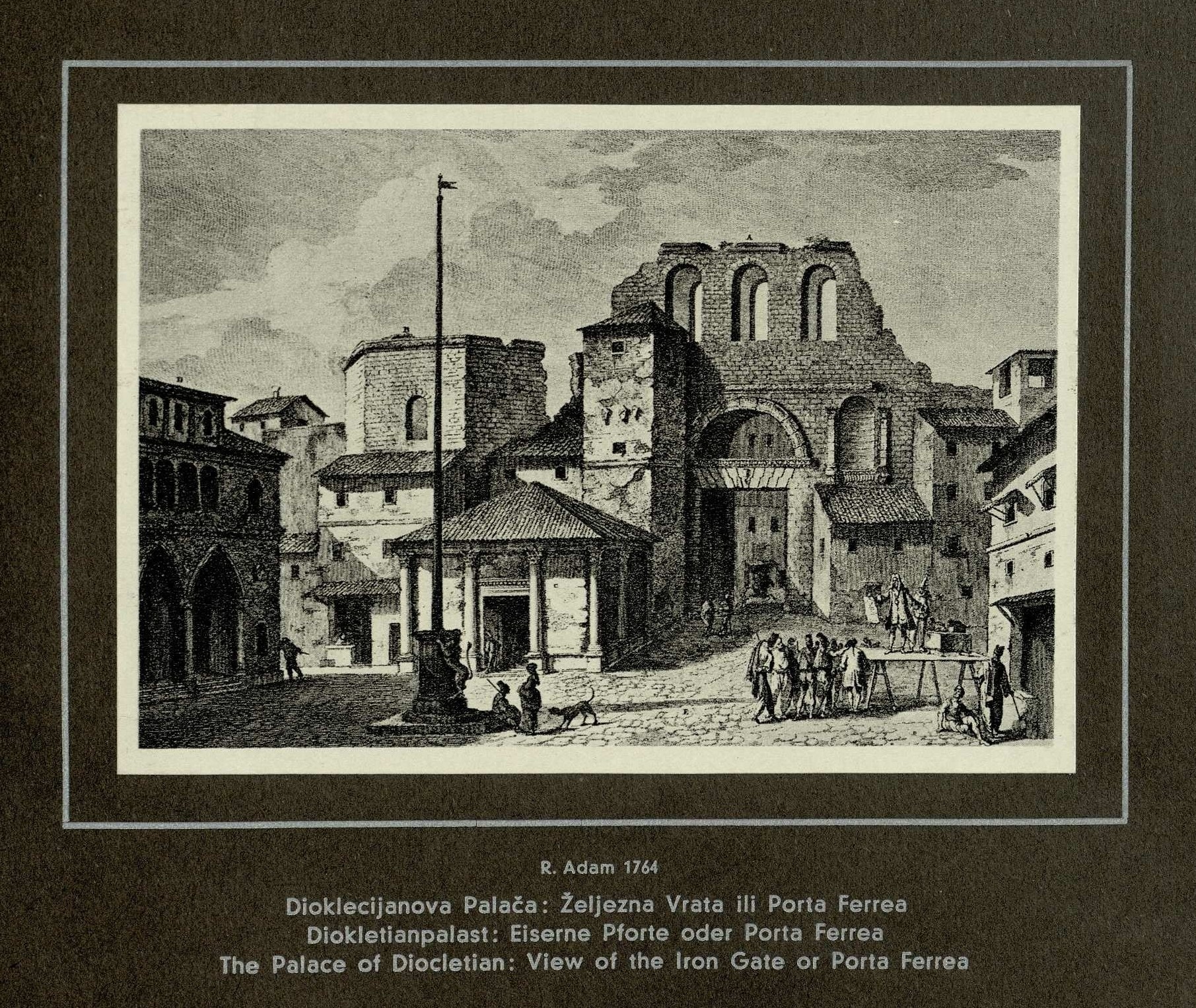

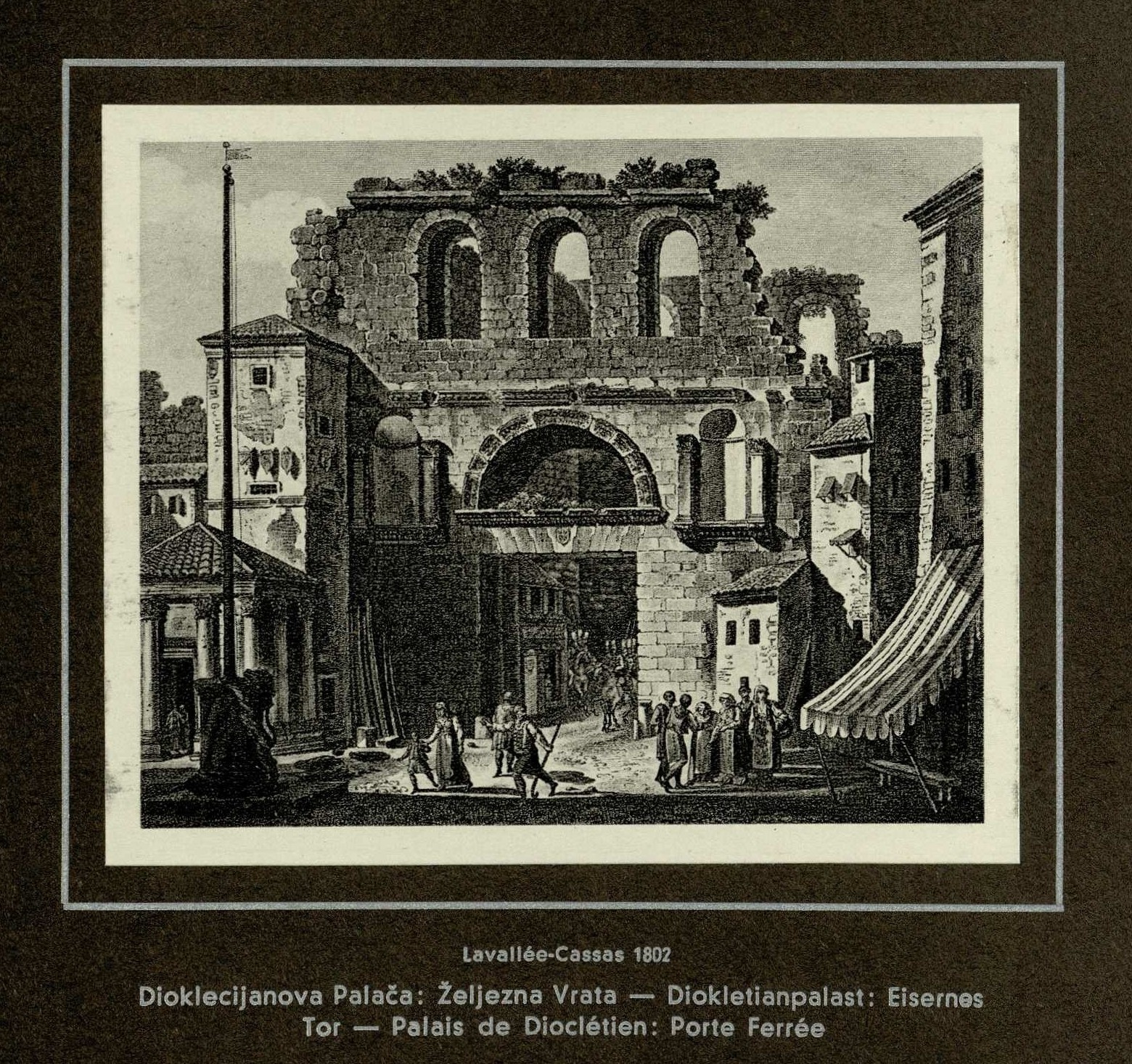

There were originally four principal gates pierced in the middle of each wall. After the end of the Middle Ages the main gate or Northern Gate, the most ornamented, with its bracketted colonnettes and arcadings that seem to have been imitated by Theodoric in his palace at Ravenna, was called Porta Aurea or Golden Gate; the Eastern Gate or Porta Argentea or Silver Gate has thoroughly disappeared, and a mean Venetian doorway has taken its place; the Porta Ferrea or Iron Gate or Western Gate, capped with a coquettish campanile still admits from the newer town or burgus to the precincts of the ancient one; Southern or Brazen Gate or Porta Aenea is a simple and only two meters wide outlet to the sea. — Each of these gates, except that of the south front, had a square vestibule, the western and the northern ones are still preserved, and were flanked by two octagonal towers. — Between these towers and the square ones of the angles there rose four smaller towers of quadrangular shape, almost altogether destroyed between 1629 and 1652 save the four ones of the western front which are for the most part concealed by the walls of the houses built in subsequent times.

The residence of Diocletian had so the appearance of a fortified castle — castellum rather than of a palace, or it must have looked more like a walled town than a single building. Like all Roman villas it had very little external beauty, and certainly no picturesqueness. All surrounding walls were plain, only towards the sea the open cloister of the Cryptoporticus which occupied the upper part of the front, must have had a good effect, and at each end of this front the walls are high enough to be impressive. This open cloister runs on the front at the height of 9 m — nowadays 6.50 m and was decorated with 52 columns and three loggias, one in the midst which is gone and one at each of the two ends which are partly preserved. The Cryptoporticus supported probably a terrace and was used as a walking place of the emperor.

The main streets of the palace meeting in the middle of the quadrangle shew the style of a Roman cardo and decumanus. Two of them crossing one another divided the palace into quarters, except that the main street, running north and south, was not continued through to the south but was interrupted by the imperial apartments. The two northern quarters of buildings were intended to the use of the imperial guard, of the household and stalls of the emperor, and the southern two to the imperial apartments.

Entering by the Porta Aurea, one would have found oneself in a street twelve meters wide running between massive arcades straight to the vestibule of the imperial residence, and advancing along this street southwards about 100 m, one would have found oneself in the centre of the Palace, where the two main streets crossed with a view between arcades right and left to the Porta Argentea eastwards, and the Porta Ferre a westwards.

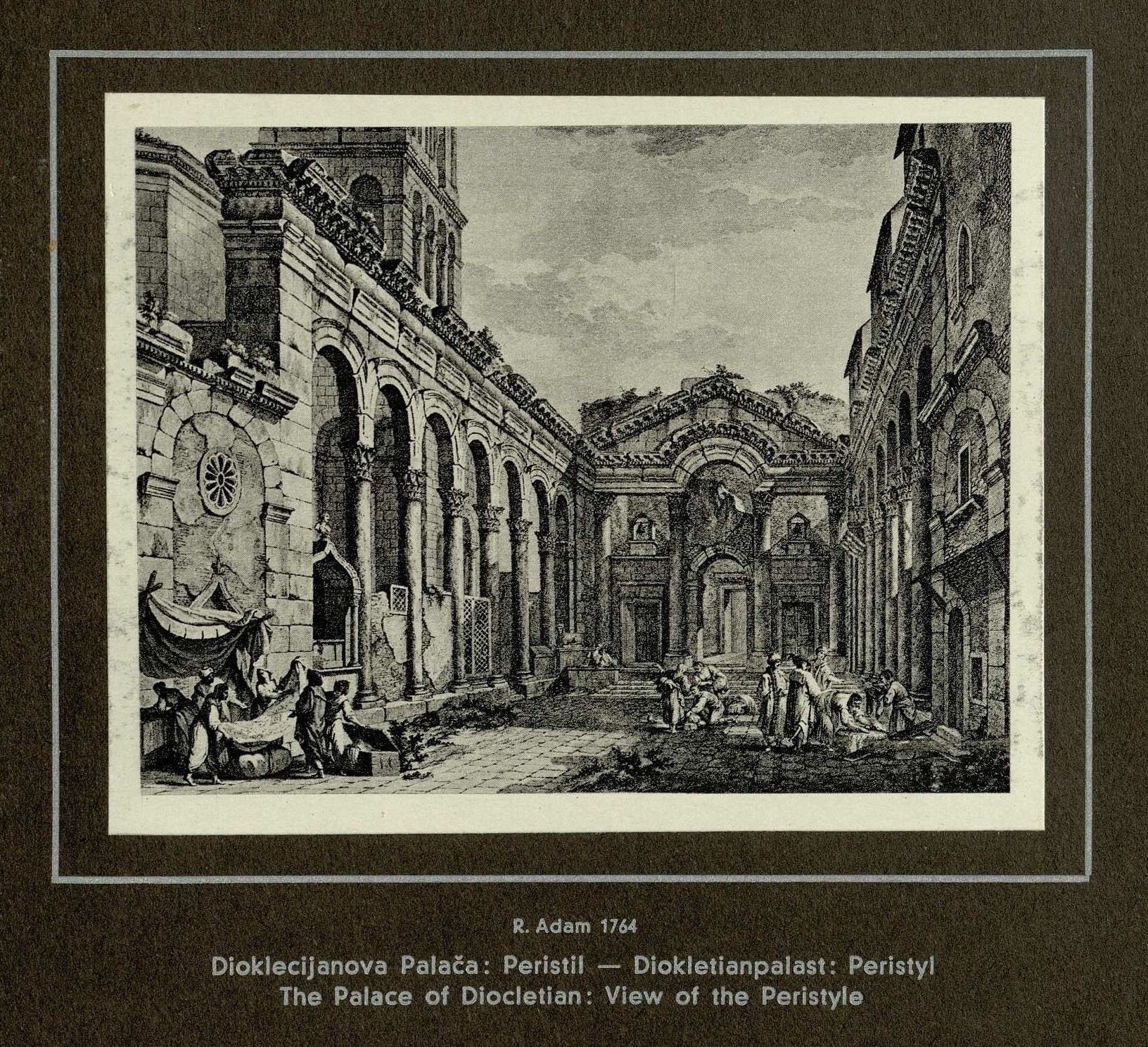

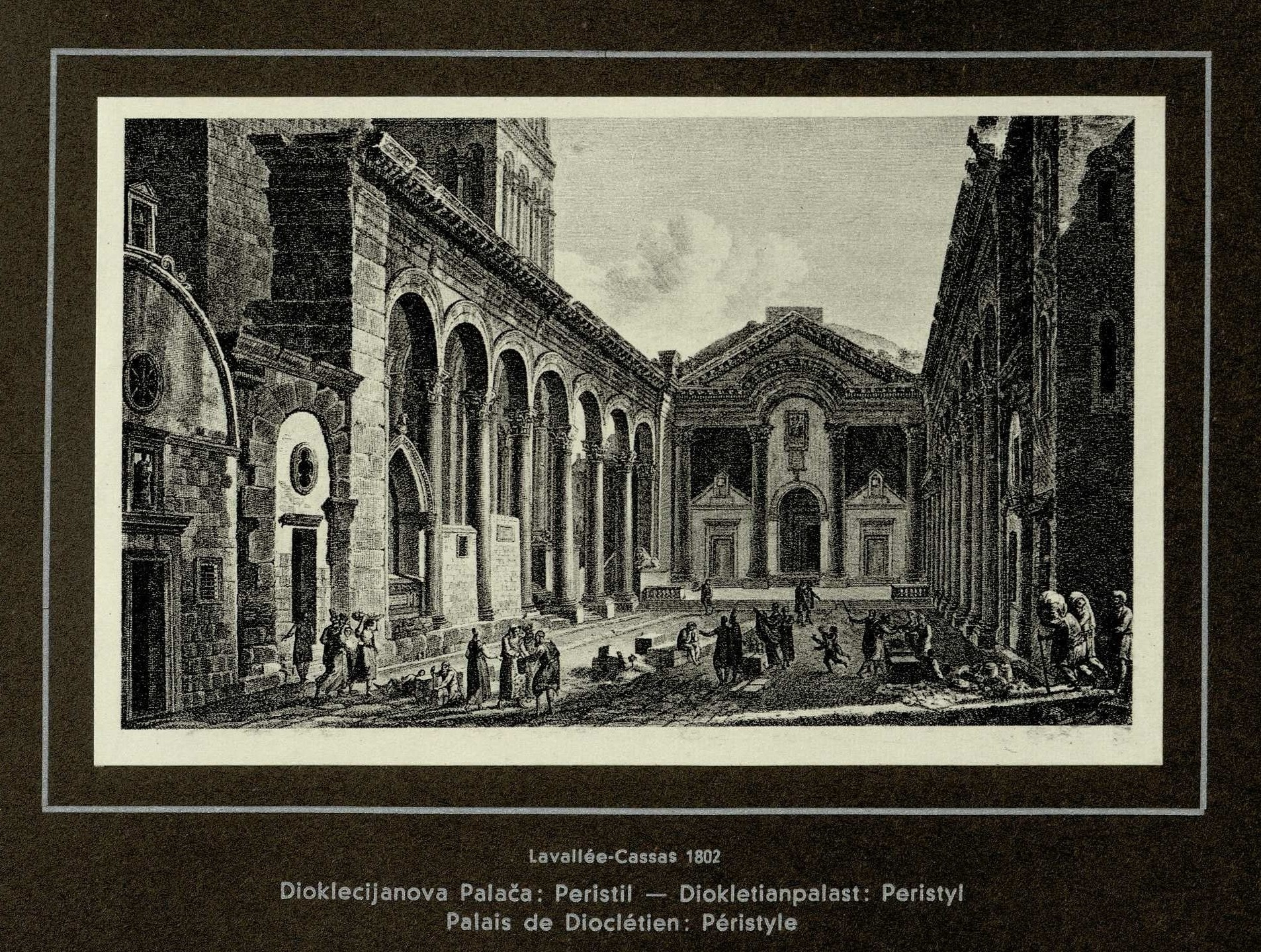

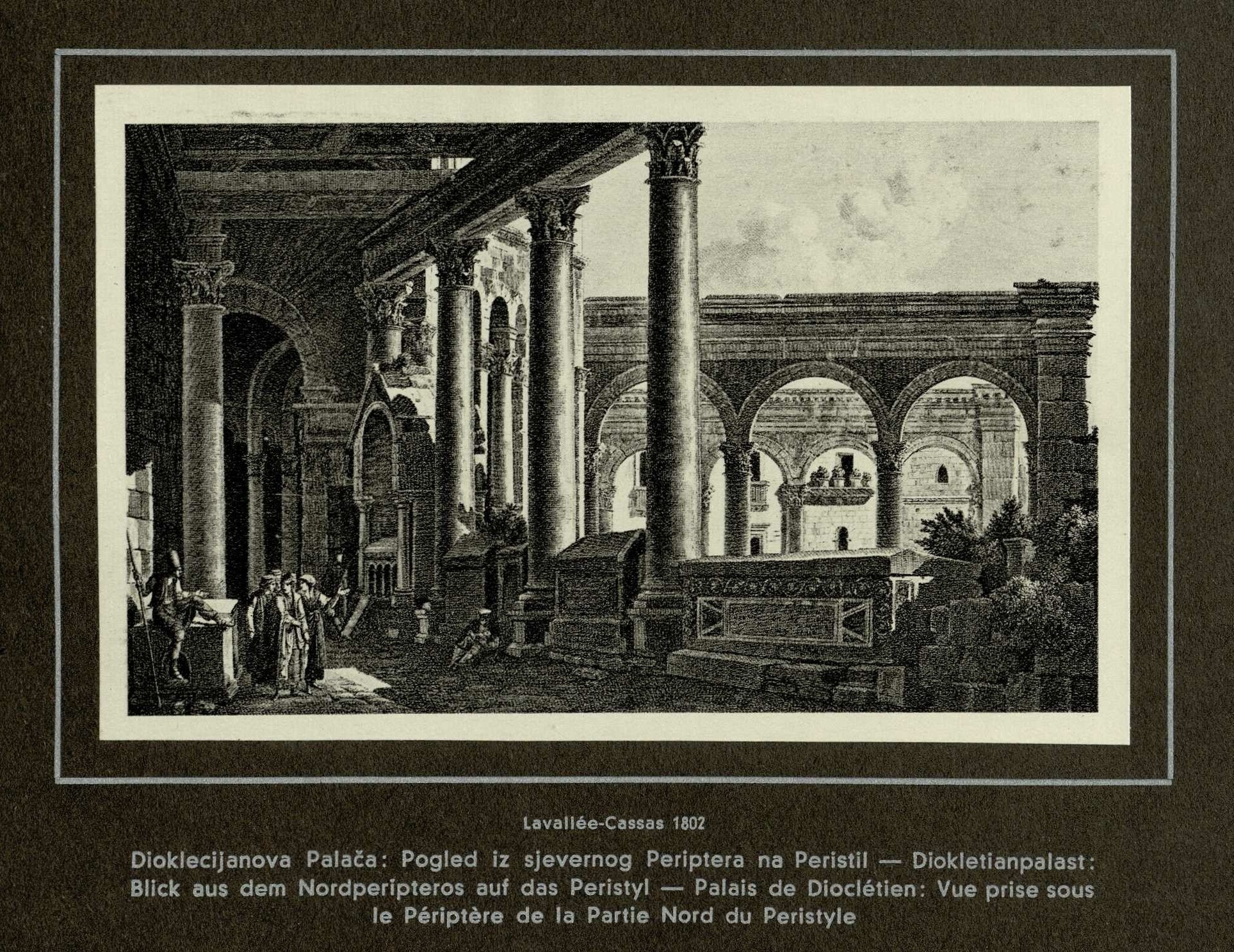

This centre or Peristyle is an almost perfectly preserved square 51m long and 12 m wide, adorned by 16 columns. Everything as far as the entrance to the imperial apartments remains to this day. Beyond the crossing the low simple arcades of the north street were exchanged for the lofty and graceful columns and arcades of the Peristyle, forming on either hand an open screen through which were seen enclosed courts, right and left, each containing a monument, the Mausoleum to the left, the Temple of Jupiter to the right. Architecturally the most important of the many striking features of the Palace is the arrangement in the Peristyle by which the supporting arches spring directly from the capitals of the columns. This, as far as the known remains of ancient art are concerned, is perhaps the first instance of such a method.

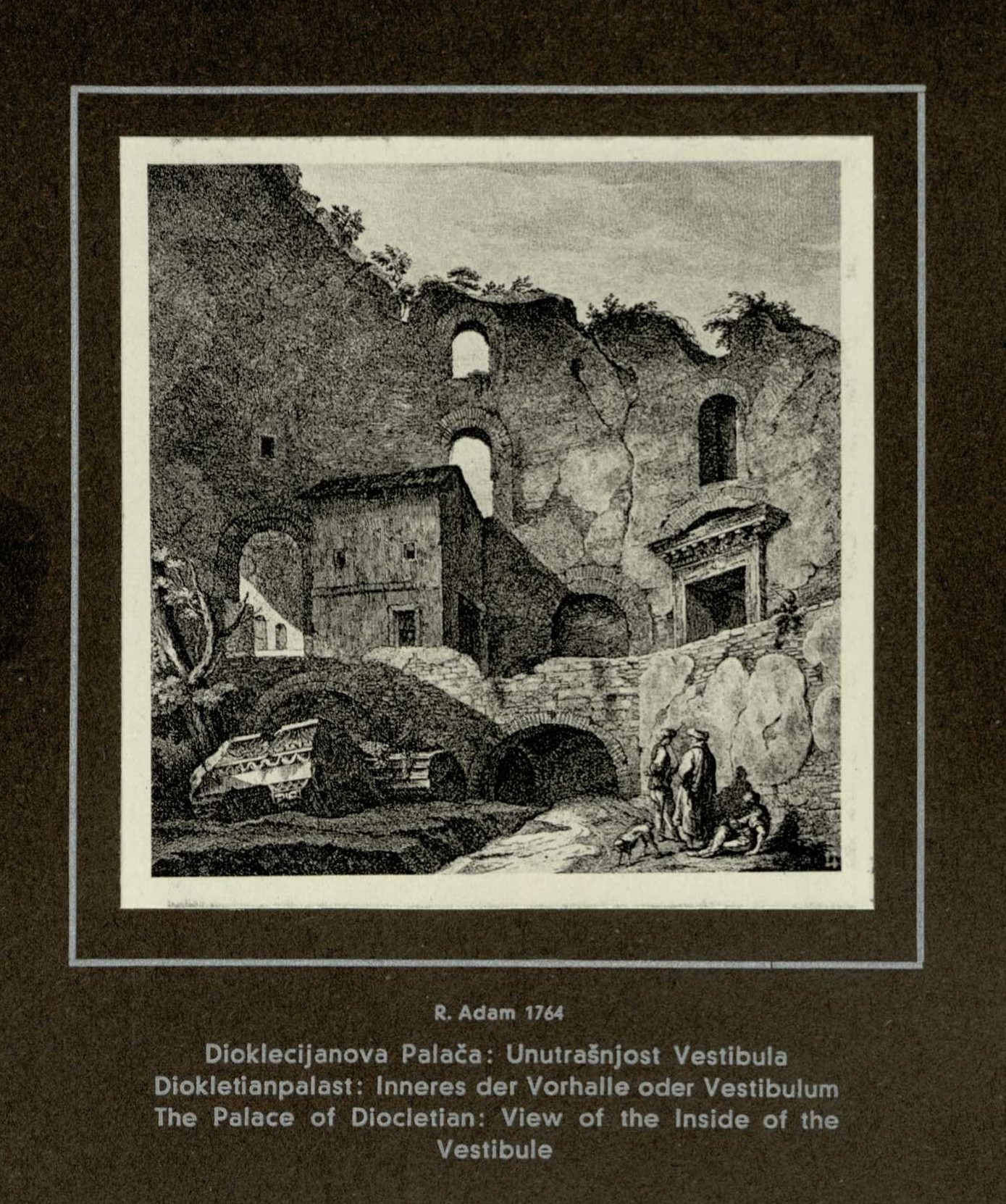

Passing through the Prothyron we enter firstly the circular Vestibule, which has now unfortunately fallen in, but still preserved, and then in the Tablinum or the Great Hall of the Court; to the right there was a set of six living-rooms for the guests of the emperor, next to them the library and the cabinet, further on the Exedra or waiting-room, the sleeping-room and the bath-room. To the left side of the great-hall there were disposed six spare rooms for the women, the kitchen and accessories, the Triclinium or dining-room, the lodgings — Nympheum for the empress Prisca and her daughter Valeria who never came in the Palace owing to political motives arisen from the fourth edict forced upon the emperor by his collegue Galerius.

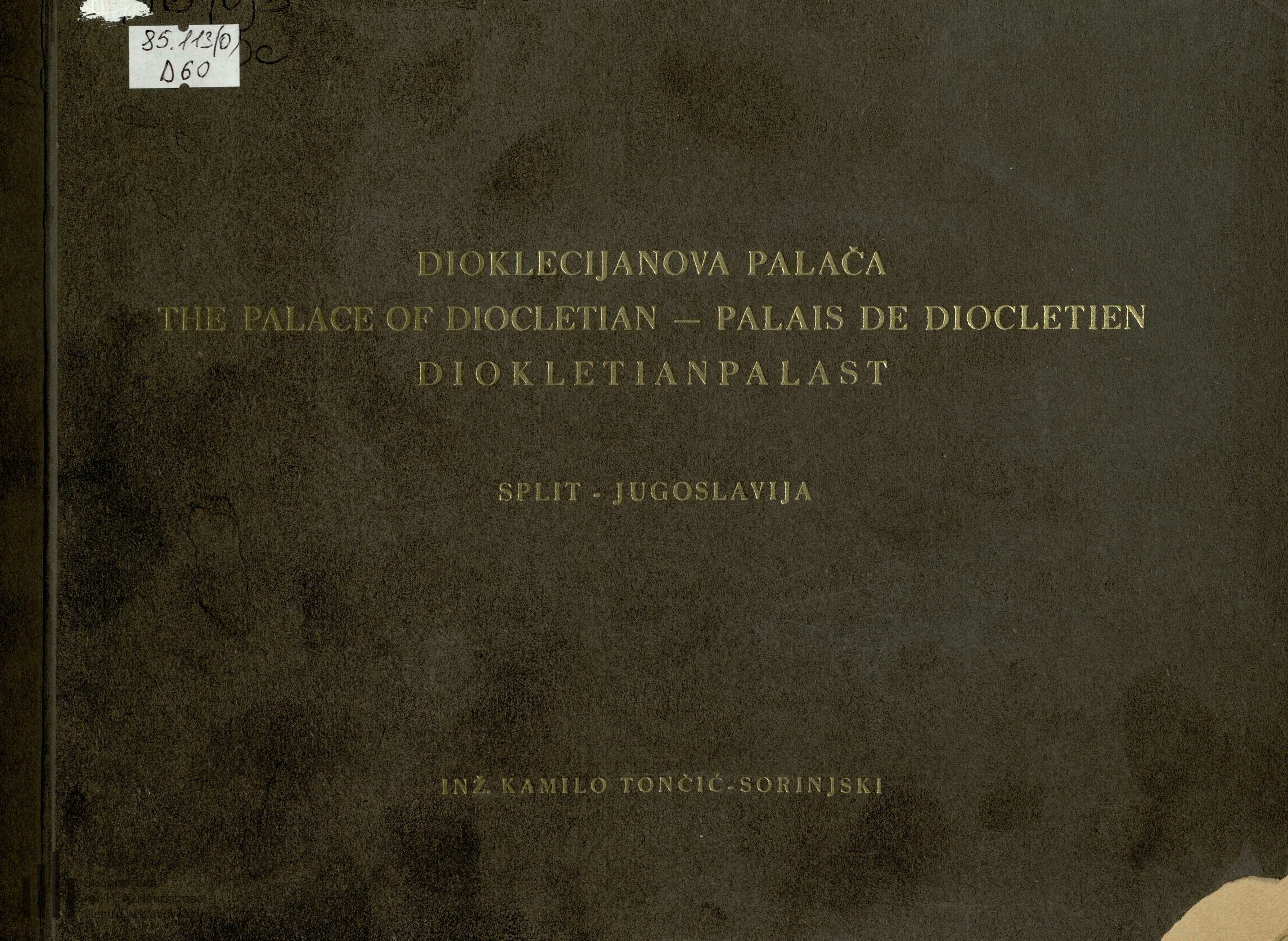

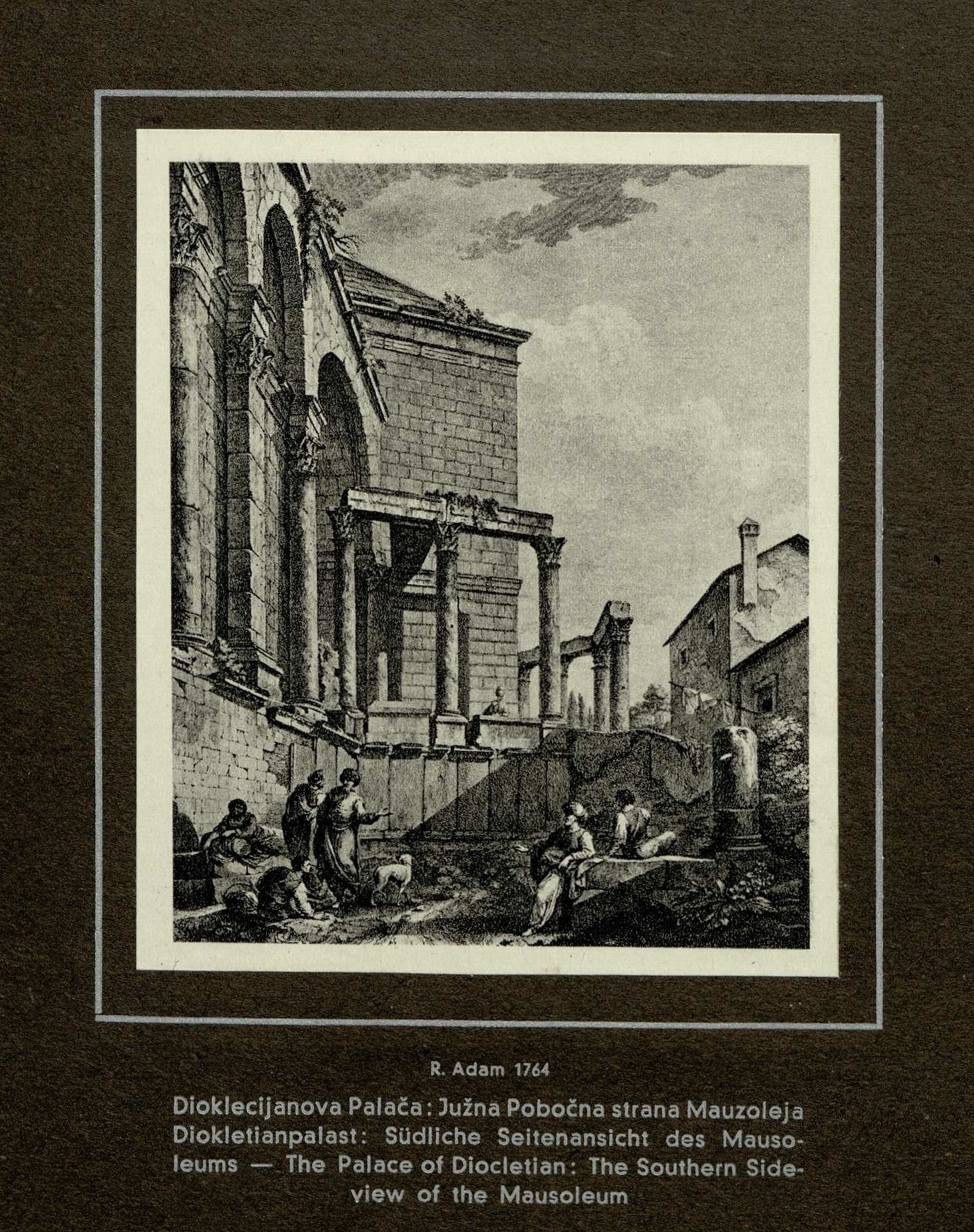

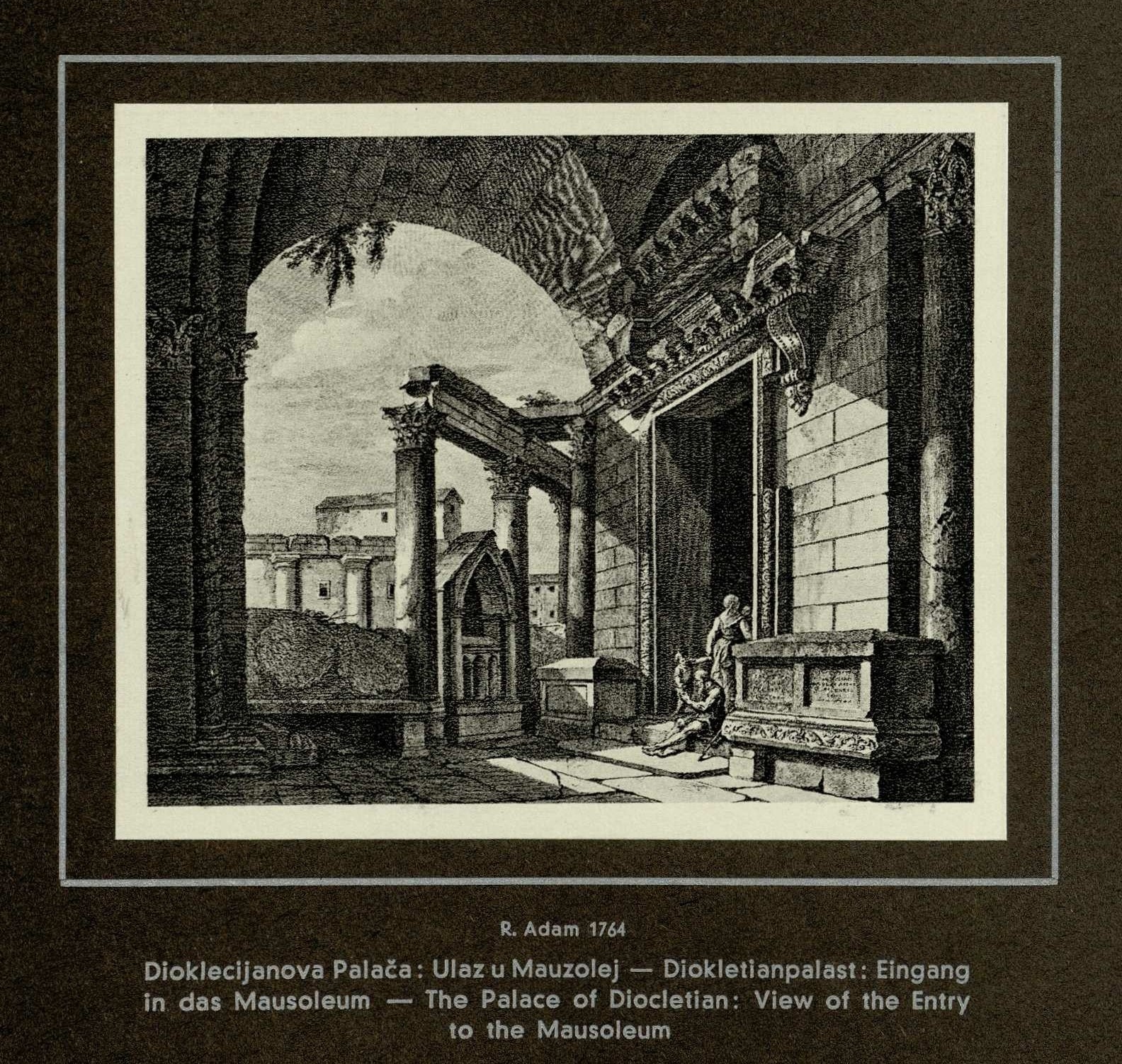

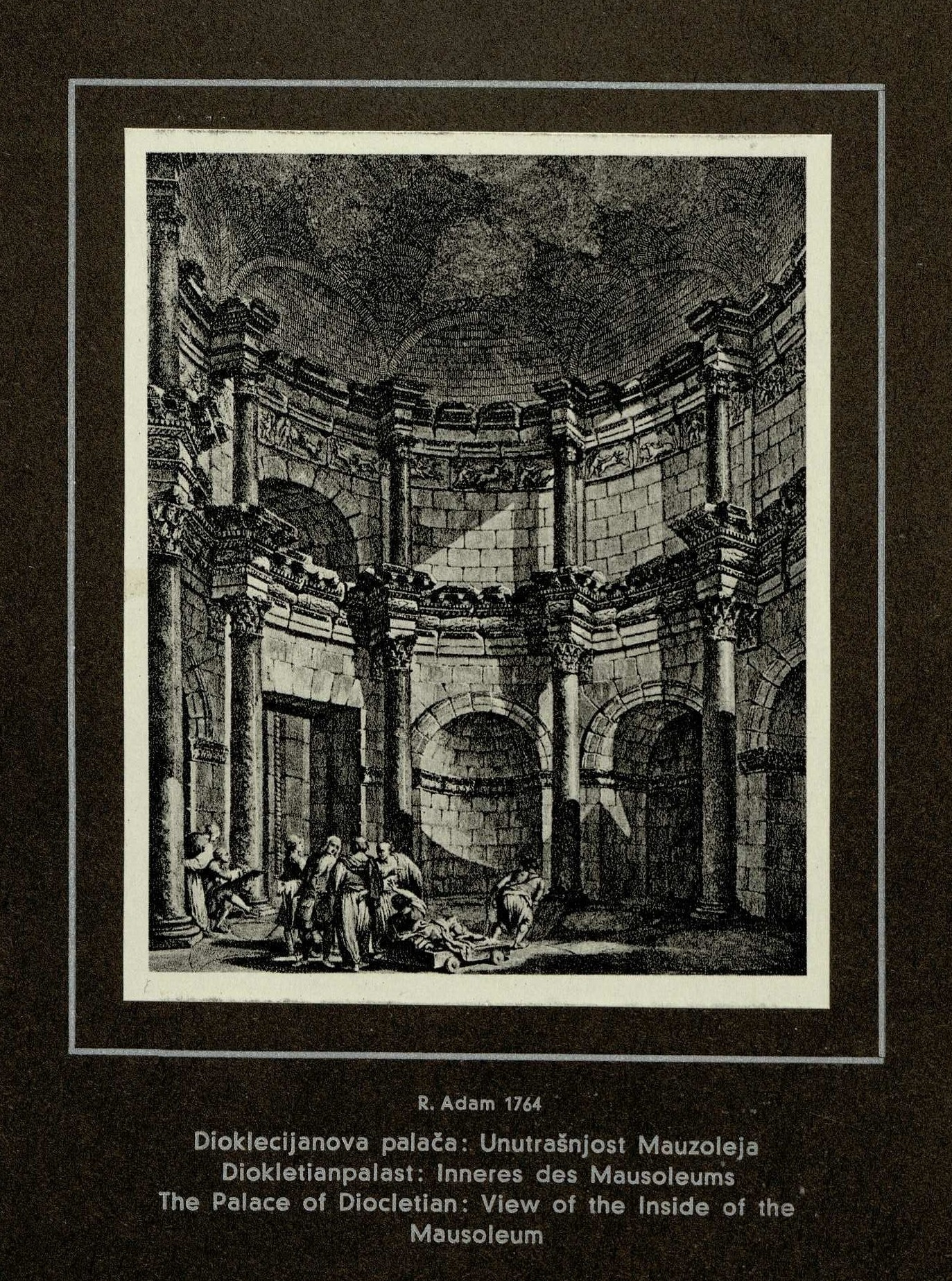

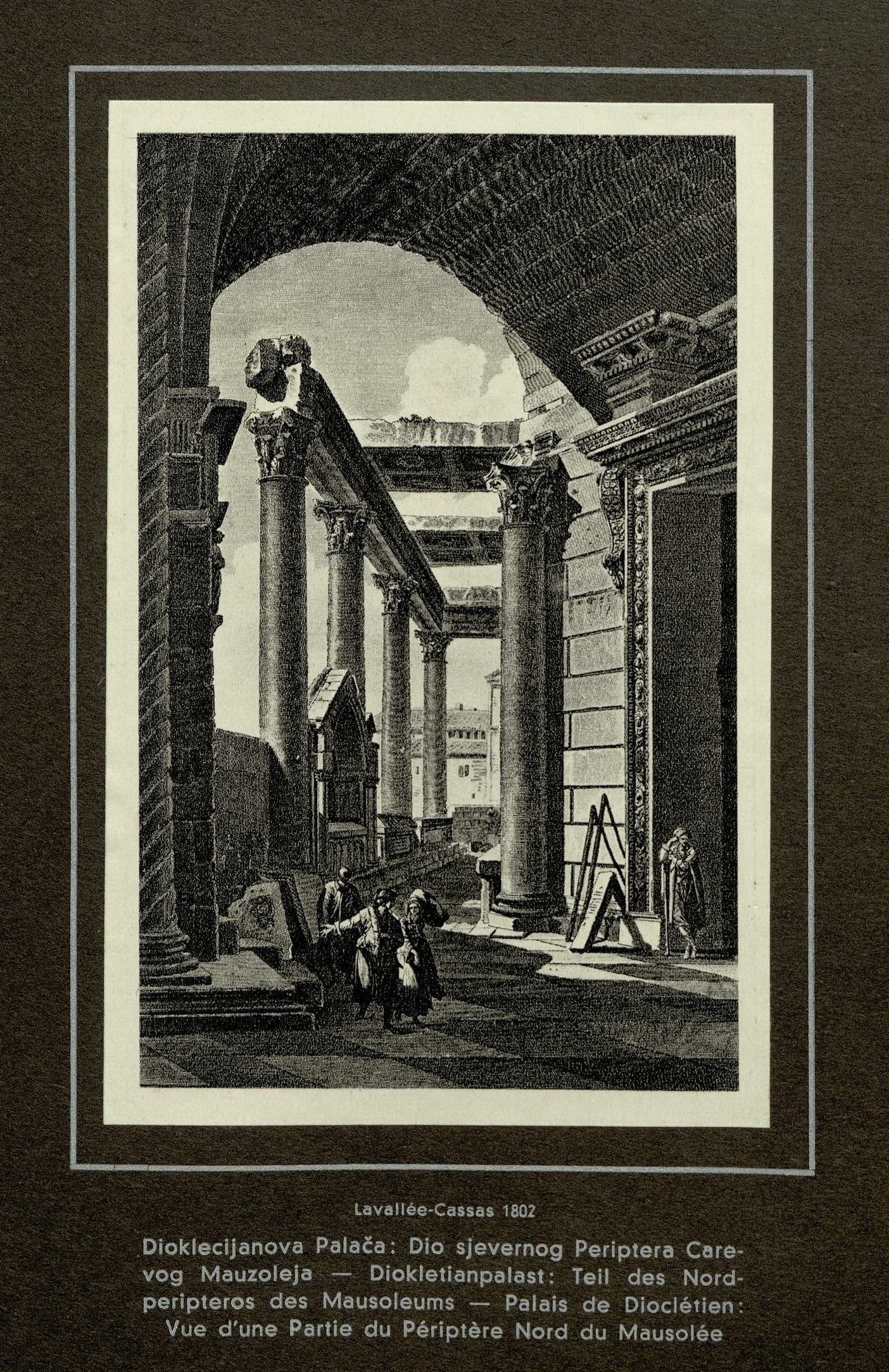

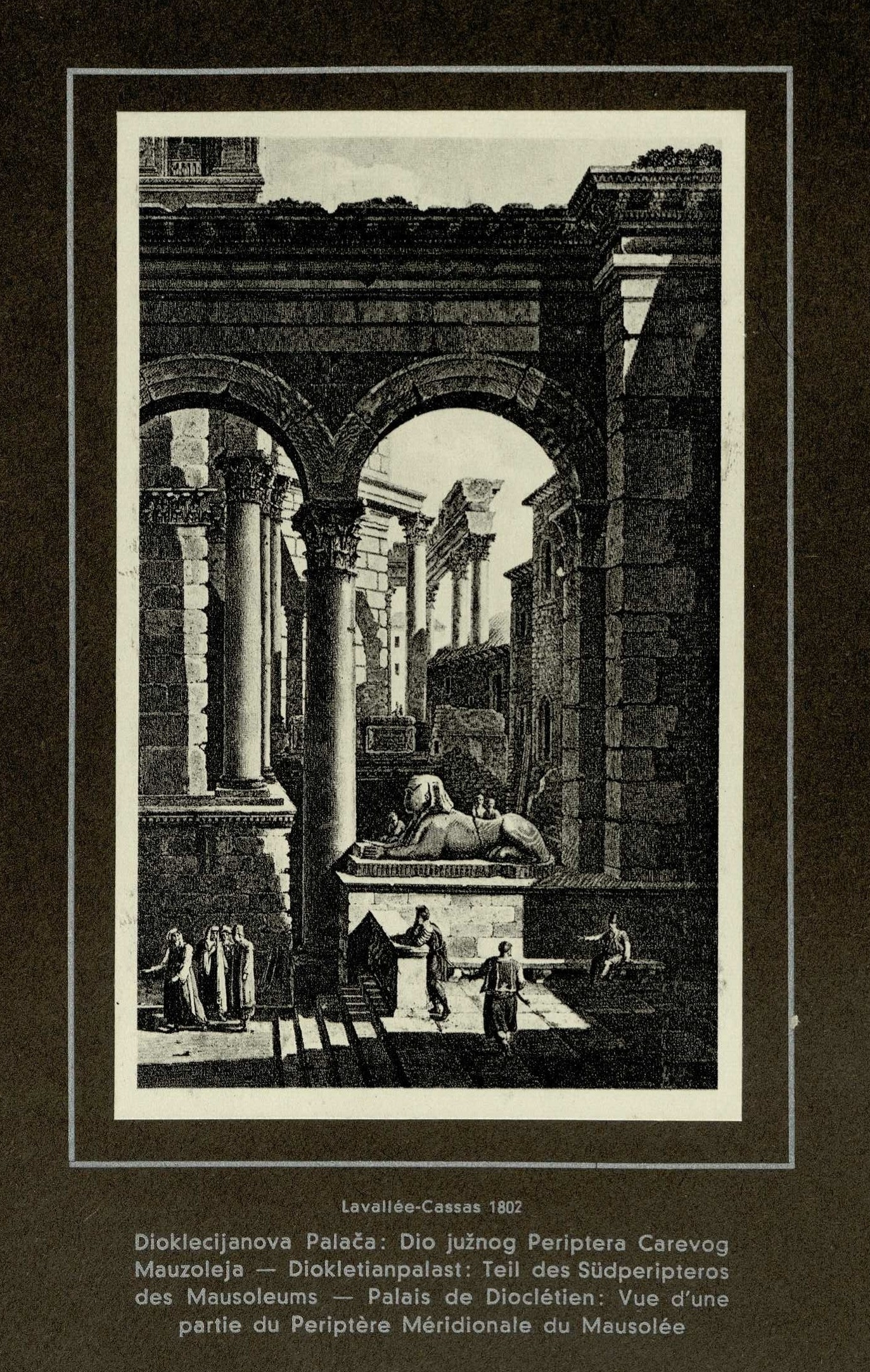

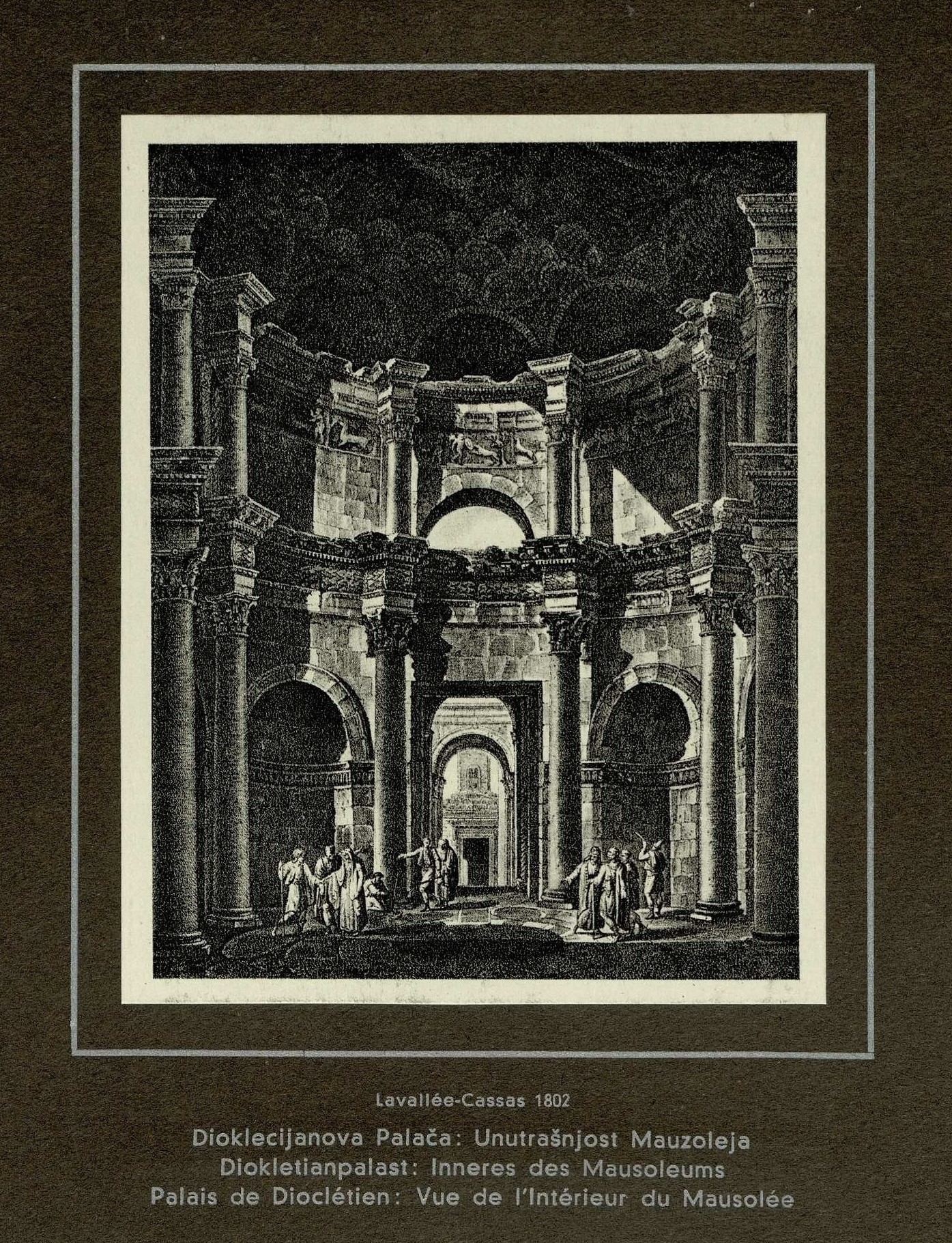

From the peristyle, with his columns of cipollino and rose-coloured granite, a flight of steps leads to the Mausoleum. The building is externally an octagon surrounded by a peristyle of his own — the Peripteron, and had originally a projecting portico in front — the Prostasis, but the latter is now supplanted by a splendid mediaeval campanile entirely renewed at the end of the 19th century. The interior is circular and covered by a dome once set with mosaic. The circular wall is divided into eight bays by detached columns two orders in height, those of the lower order of granite, those of the upper of porphyry and granite in alternate pairs, the capitals of the former being of Roman character and those of the lower of Greek character. Between the two orders of columns is a frieze consisting of little figures of winged boys riding on horseback or driving chariots, or engaged in the chase with hounds in pursuit of stags or goats, or fighting with wild beasts. Among these a few masks with festoons and some medallions among which Hermes Psychopompos and the portraits of Diocletian and Prisca may be presumed.

In the quadrangular niche, opposite the door was placed the sarcophagus of Diocletian, but it finally disappeared in the eighth or nineth century. Two or four sphinxes were set on either side of the steps leading up to the monument to be as it were the watching guardians of the imperial tomb!

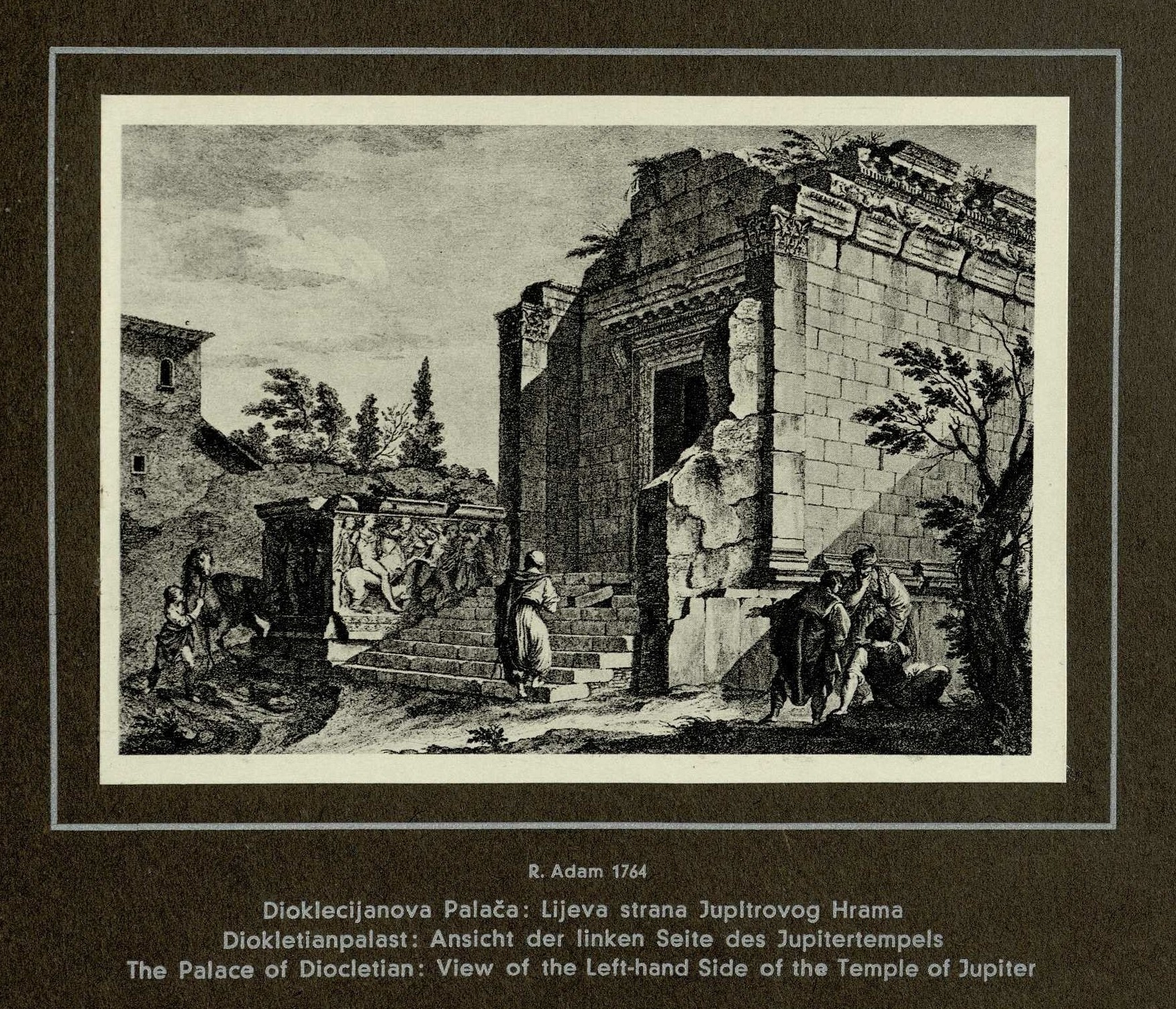

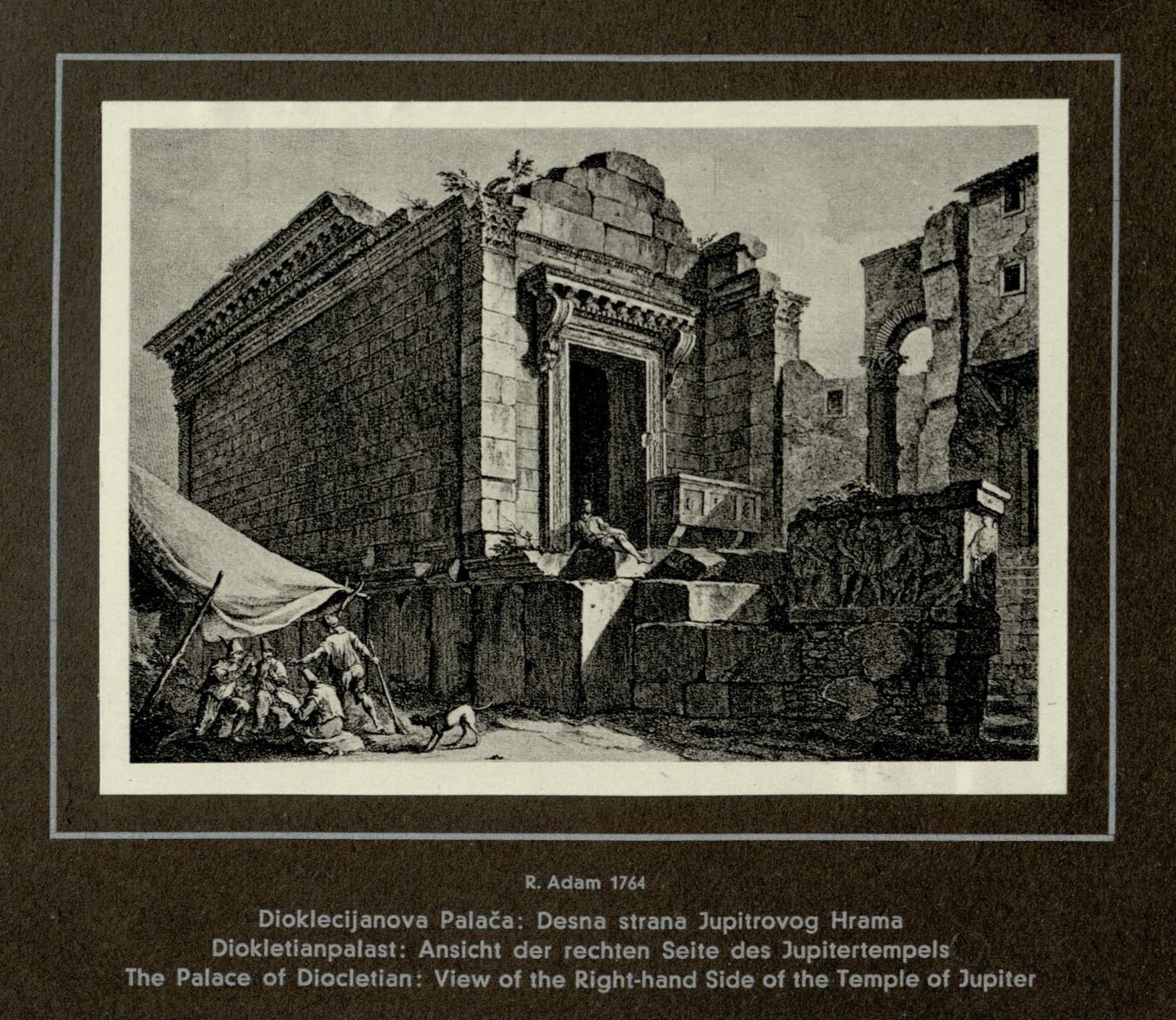

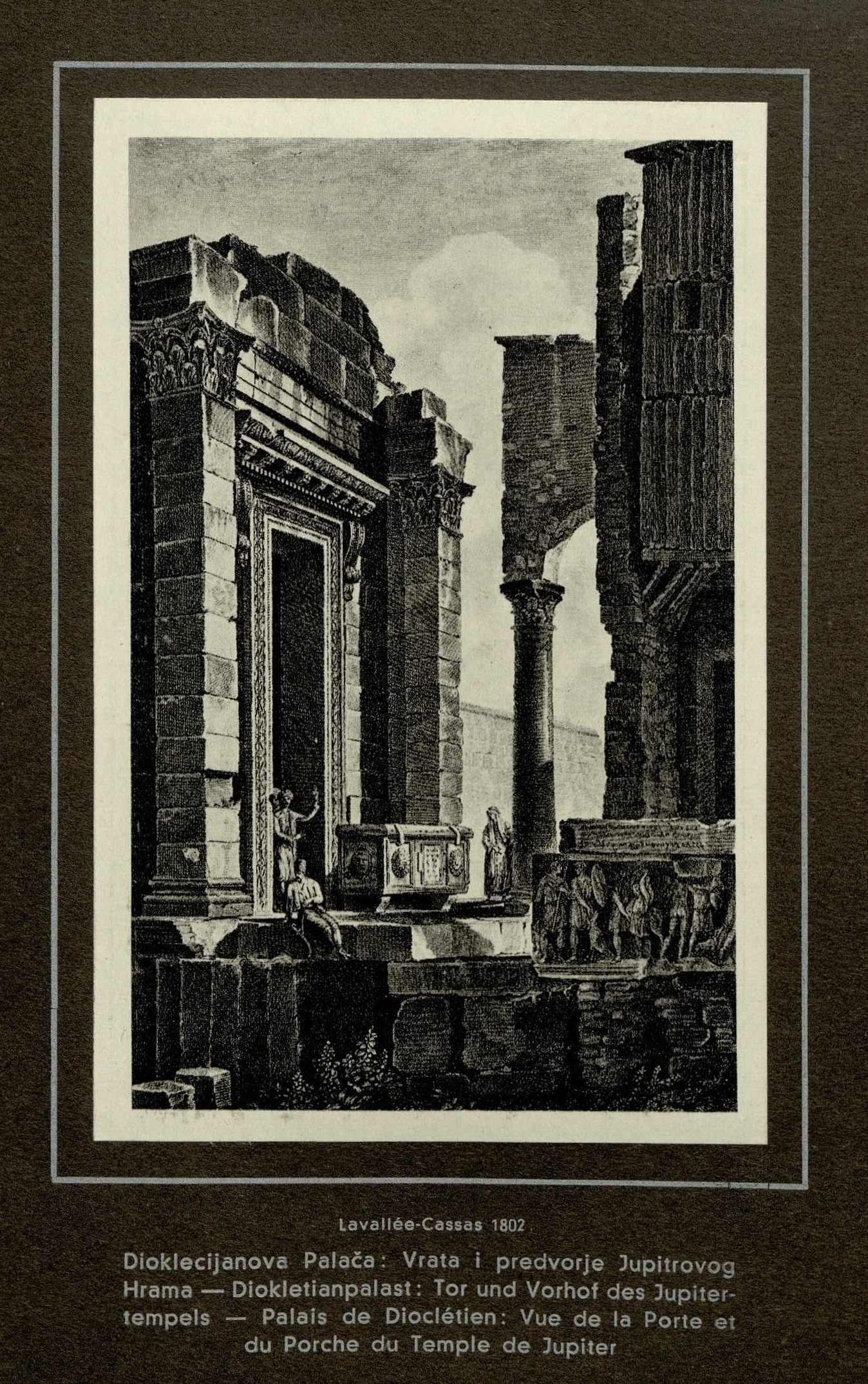

Opposite the Mausoleum is the Temple of Jupiter, now the baptistery of Split. It was a small rectangular temple on a lofty podium with a tetrastyle pronaos or front portico and two pilasters on the wall, consequently an exastylos prostylos in antis. The cella, which is, perhaps the best preserved cella in existence, is covered by a semi-cylindrical roof finishing at either end with a triangular pediment, and by a fine waggon vault of stone sunk into coffers. The portico has gone and with it the triangular pediment which crowned it, but the rest of the building, included the barrel vault is perfectly preserved.

The great doorway of the temple is surrounded by scrollwork, with little figures and animals introduced among the ornament. Its work is still classical, but it shows details announcing the byzantine art.

Diocletian, emperor 284—305, was born probably near Salona, the capital of Roman Dalmatia, in the year 245. On the twentieth anniversary of his accession he abdicated at Nicomedia and withdrew into his Palace built in the meantime. After his death in 313 it became a property of the state or rather estate of the Crown, and its northern part was turned in a factory for military cloth weaving in which the staff of the workers were women — Gynaeceum Ioviense, whilst the imperial apartments retained their former use.

After the fall of Salona in 615 under the strokes of the Avars who were followed by the Croats, the inhabitants fled at first to the neighbouring islands, but a short time after, taking the opportunity of friendly intercourse with their Slavonic neighbours, they returned in considerable numbers to the empty house of Diocletian and made it their final settlement, beginning to reestablish civil order, and in that way they founded the town of Split.

This name is derived from the Greek word 'σκαλευτρον' — »skaleutron« — which means the »poker«, according to the shape of the peninsula on which Split is situated resembling an ancient Greek poker; thence were formed the denominations of Aspalathos, Aspalathum, Spalatro, Spalato, and the Croatian Split.

For a long time past archaeologists, writers, artists, and travellers were captivated by these peculiar ruins and they conceived the idea of giving a description of the Palace. Andrew Palladio, the renowned Italian architect of the 16th century and successor of Michelangelo in the construction of the Saint Peter’s church at Rome, had left two designs of the Mausoleum which are nowadays kept in the Library of the Royal Institute of British Architects at London.

In 1678 a physician and antiquary of Lyons, Jacques Spon, published a diary of a journey made in company of an Englishman, George Wheler, under the heading of Voyage d’Italie, de Dalmatie et du Levant, Lyon, with a description of the Palace and several details accompanied by drawings of the monuments which had stroken their attention. Wheler resumed the theme on his own authority and published it some time later under the heading of »Journey into Greece by George Wheler Esq., in company of Dr. Spon of Lyons«, London 1682, which he caused to be translated in French, and Menudier, on the other hand, translated it in German and published at Nürnberg in 1690.

But it was not before half a century after the publication of the accounts of Spon and Wheler that a first general reconstruction on paper was attempted. That was performed by the great Austrian architect Fischer von Erlach in 1735 in a thoroughly fantastical drawing which was inserted in the big work on religions history of Dalmatia of the Venetian Jesuit Daniele Farlati: »Illyricum Sacrum« 1751—1775.

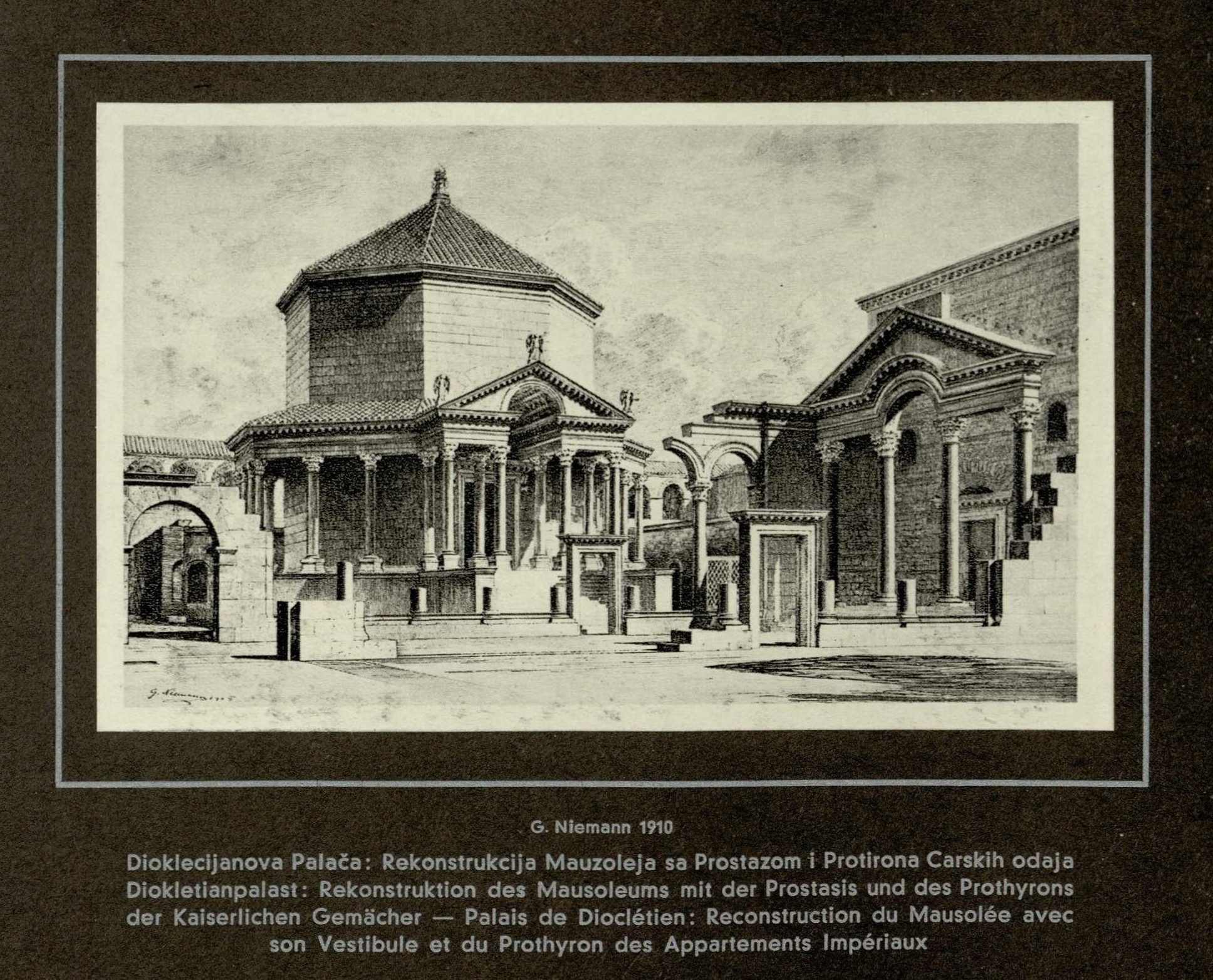

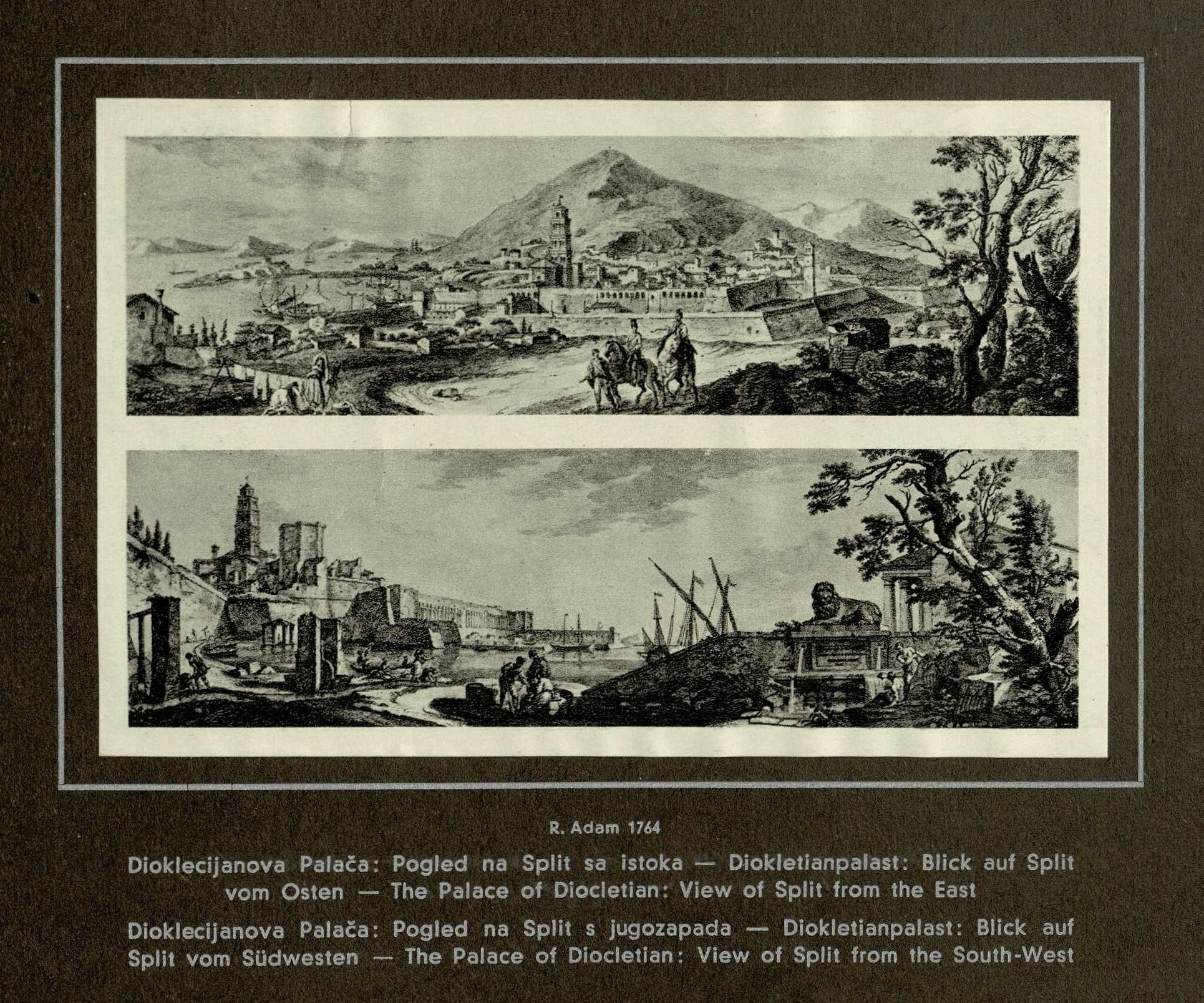

This restauration however ranks by far below the epoch-making work of the English architect Robert Adam, one of the »Adelphi«, the inventor of that style of architecture which was transplanted from England to France and hencefrom, under the denomination of Empire, applied all over the world.

It is further to be noticed a work more, published at Paris in 1802: »Voyage pittoresque de l’Istrie et de la Dalmatie, publié d’après l'itinéraire de L. F. Cassas, par Joseph Lavallée«, which is of some interest in so far as it is a simple plagiarism from the rich treasury amassed by Adam.

But at the beginning of the 20th century time was come already proper to synthesize all the results acquired in hundred years past and to attempt a general work on reconstruction like that of Adam, and to perfect it. For that purpose two important works came out: Mr. Niemann Georg, architect and professor in the Fine Arts Academy at Vienna published his work: »Der Palast Diokletians in Spalato«, Vienna 1910, and hereafter, in 1911, the fine work of »Hébrard-Zeiler, Le Palais de Dioclétien: relevés et restaurations par Ernest Hébrard, texte par J. Zeiler, with a preface of M. Charles Diehl, and, at last, with an explication of the hieroglyphical inscriptions on the footing of the Sphinx.

Whereas Niemann employed some years to survey in the slightest details all the remains of the Palace in existence, the gifted French architect, owing to his independent and deep researches, achieved a reconstruction which surpassed all the precedent attempts. It has been admired on the exhibition of the French »Salon des Artistes«, and it procured to the author the »Médaille d’Honneur«.

We have published this collection of pictures on the purpose both to procure diffusion to this treasure of the antiquity and to offer to the lovers of arts instruction and pleasant entertainment — Utile dulci.

Все иллюстрации издания

Скачать издание в формате pdf (яндексдиск; 49,6 МБ).

31 августа 2022, 10:22

0 комментариев

|

Партнёры

|

Комментарии

Добавить комментарий