|

|

Dmitri V. Sarabianov. Russian art : From Neoclassicism to the Avant Garde : 1800–1917 : Painting, Sculpture, Architecture. — New York, 1990  Russian art : From Neoclassicism to the Avant Garde : 1800–1917 : Painting, Sculpture, Architecture / Dmitri V. Sarabianov. — New York : Harry N. Abrams, Inc., Publishers, 1990. — 320 p. : ill. — ISBN 0-8109-3750-6

If, as Winston Churchill put it, Russia “is a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma,” the wraps are coming off now. And among the most exhilarating discoveries for the world outside are little-known aspects of Russian art.

As the eminent art historian Dmitri Sarabianov tells us in this lively book, Russia first turned its face to Europe at the beginning of the eighteenth century, when Peter the Great started the momentous process of “catching up” with the West. By the start of the nineteenth century, European ideas had been assimilated into the rich substratum of Russian culture and a unique amalgam began to emerge. Professor Sarabianov traces the passage of Classicism, the last vestige of the eighteenth century, as it gives way to Realism, and the accompanying triumphs of Russian portraiture. Other indigenous subjects—peasant life, religious ritual, historical confrontations, landscapes with the ubiquitous birches, urban boulevards—became the focus of Russian art. In architecture there was a parallel stylistic development: elegant classical facades gave way to reconstructions of medieval Russian buildings.

In 1870, the Society for Traveling Art Exhibitions, whose members were known as the Wanderers, was founded. Its dual purpose was to educate the people through traveling exhibitions and to work for social reform. In these concerns, the Wanderers presaged the Populist goals that were among the driving forces behind the 1917 Revolution.

At the turn of the century, the dominant mode was Symbolism, exemplified by such works as Mikhail Vrubel’s The Demon. But Modernist tendencies and other currents were simultaneously gaining strength and displacing “Russian Impressionism,” as Professor Sarabianov skillfully shows. The World of Art—a group and periodical whose aims were articulated by Sergei Diaghilev, then not yet a ballet impresario—pursued a course roughly equivalent to Art Nouveau. Some artists found inspiration in the “primitive” art on peasant signboards and in popular prints. Pieces appeared that revealed the germs of abstraction as, early in the new century, Kandinsky, Larionov, Goncharova, Malevich, Tatlin, and others began to experiment with nonrepresentational art under such labels as Constructivism, Suprematism, and Rayism. Malevich’s famous White on White, consisting of one rectangle superimposed at an angle over another, was the exemplar of the extremes of this experimentation.

These diverse aesthetics had to be rethought in 1917, when the Revolution brought the Bolsheviks to power. Functional, applied design came to the forefront. It is here, with the close of the most brilliant and innovative period in Russia’s artistic life so far, that Professor Sarabianov ends his account of the pivotal years that led to the dazzling abstract, geometrical breakthroughs of Russian art in this century.

Even specialists in Russian art will find unknown and surprising works here. Many of the 354 plates (81 in full color) have never been seen outside the Soviet Union. In treating architecture and such applied arts as book illustration—in addition to painting and sculpture—Professor Sarabianov emphasizes the democratization of art in the Soviet Union.

Dmitri Sarabianov is superbly equipped for the task he has undertaken in this volume. He has published more than 250 books and articles on Russian art, chiefly of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, including monographs on numerous artists. Valentin Serov, Pavel Kuznetsov, Ilya Repin, Alexei Venetsianov, and Robert Falk among them. His biography of Liubov Popova is soon to be published by Abrams. A corresponding member of the Academy of Sciences of the U.S.S.R., he is a veteran of World War II and teaches in the Department of Russian and Soviet Art History of Moscow University.

CONTENTS

Foreword 7

PART I. 1800–1860

1 The End of Russian Classicism ... 11

2 Early Romanticism ... 27

3 Early Realism ... 47

4 The Fate of Romantic Academic Art ... 57

5 Alexander Ivanov ... 68

6 The Beginnings of Critical Realism ... 86

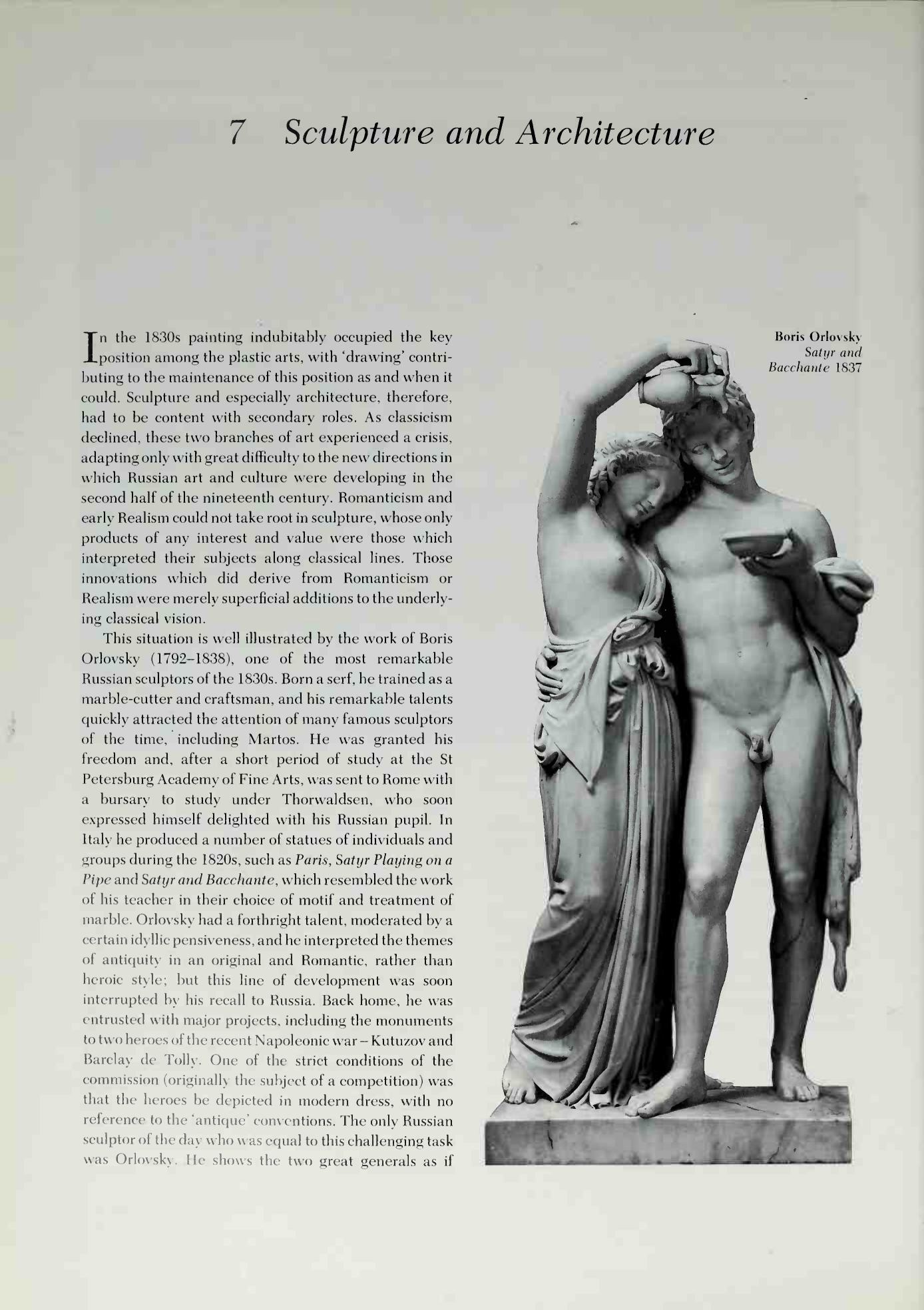

7 Sculpture and Architecture ... 94

PART II. 1860–1895

1 The Realists of the 1860s ... 102

2 The Society for Travelling Art Exhibitions ('The Wanderers') ... 111

3 Genre Painting and Ilya Repin ... 133

4 History Painting ... 146

5 Landscape Painting ... 160

6 Sculpture and Architecture ... 182

PART III. 1895–1917

1 The Beginnings of Symbolism and Russian Art Nouveau ... 201

2 From Impressionism to Russian Art Nouveau ... 207

3 The Moscow Painters ... 213

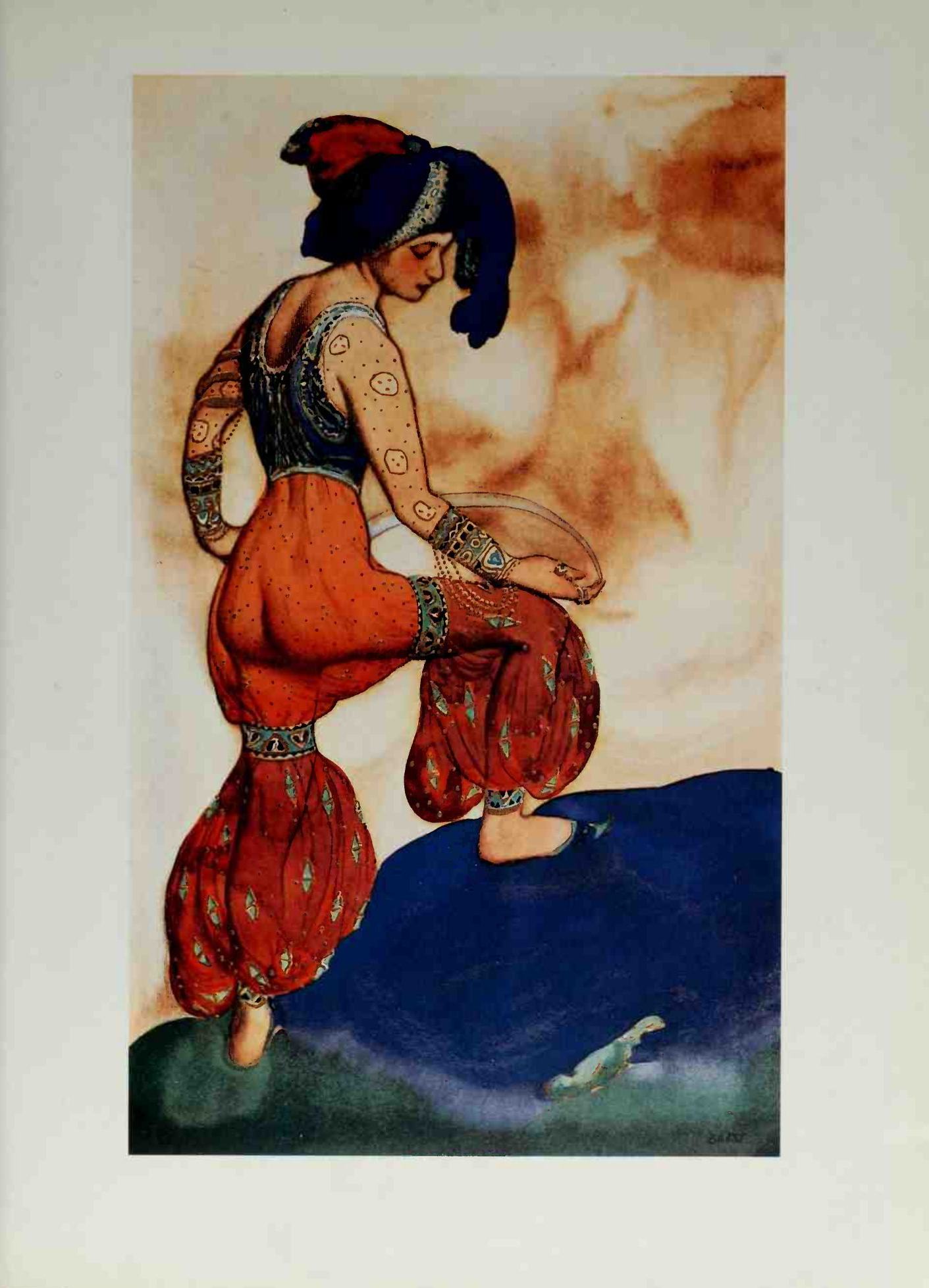

4 The ‘World of Art’ Group ... 222

5 The ‘Blue Rose’ Group ... 232

6 The ‘Knave of Diamonds’, the ‘Donkey’s Tail’, and Neoprimitivism ... 249

7 The Avantgarde ... 269

8 Sculpture and Architecture ... 293

AFTERWORD ... 305

NOTES ... 306

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY ... 307

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS ... 308

INDEX ... 314

Foreword

Anyone familiar with Russian avantgarde painting, and with artists such as Mikhail Larionov, Natalia Goncharova, Marc Chagall, Vasily Kandinsky, Kazimir Malevich, Pavel Filonov and Vladimir Tatlin, may well ask the question: what were the antecedents of this movement? To put it another way, was the avantgarde the continuation of an essentially Russian tradition, or rather the response of Russian artists to Western European influences?

The history of Russian art can help us at least to clarify the question, even if it provides no clear-cut answer. Firstly, it illustrates the relationship between the Russian avantgarde and medieval culture, and specifically the painting of ancient Rus. Secondly, we shall see how Russian art of more recent times has generally tended to develop along universal lines, if somewhat spasmodically. In other words, the great achievements of various periods of Russian art cannot be ascribed to foreign influence alone.

Russian culture experienced its first great heyday a thousand years ago, not long after ancient Rus had embraced the Graeco-Byzantine variety of Christianity. It was interrupted by the Mongol and Tartar invasion. Although this tragic event in Russian history set back the country’s cultural progress for many generations, it did have one most positive result: Europe was saved from the barbarians. Russia, however, took two hundred years to recover from the onslaught. Only after liberation from foreign domination was the nation able to regain its momentum. The fifteenth and sixteenth centuries witnessed a new flowering, above all in the art of Andrei Rublev and Dionysius, and in hipped-roof architecture. Thereafter, however, Russian civilization trod its own individual path. It was never to enjoy a Renaissance, and only threw off its medieval character to join the mainstream of European development towards the end of the seventeenth century.

The eighteenth century played a decisive part in the evolution of Russian art. These were the years when Russia finally joined the family of Europe and experienced her Age of Enlightenment. Her art successively developed the great European styles – first Baroque, and later Classicism. It was a tremendous turning-point in the life of the whole nation, and its impact was similar to that experienced by the Western European world at the time of the Renaissance. In Russia all these ideas and tendencies coincided in the eighteenth century, and it was this concentration which enabled her eventually to clear the harriers between the two worlds. The essential character of Russian culture began to manifest itself in its tendency to make up for lost time by initially making dramatic leaps forward, subsequently slowing the pace and finally almost coming to a halt. It proved its ability to perform simultaneously most of the tasks which other nations had been able to confront in a leisurely way over long periods of their historical development.

Russian art of the nineteenth century, and the beginning of the twentieth, fits into the same general pattern of stylistic change that characterizes all European art. The years covered by this book are traditionally divided into three distinct periods corresponding with the artistic and historical developments which were taking place in Russia as a whole. The first period covers the first half of the nineteenth century, whose art, though still a continuation of eighteenth-century concepts, nevertheless opened the way to new movements — Romanticism and the early and middle Realist schools. The second period stretches from the mid-fifties to the nineties, the years when Realism achieved its apogee and thereafter went into decline. The last of our three periods, which includes the end of the nineteenth century and the first two decades of the twentieth, comes to an end with the Revolution of October 1917. These years saw an explosion of ideas and rapid artistic renewal which found their finest expression in the Russian avantgarde.

But not only in the avantgarde. Russian art of the nineteenth century also had its heroes – Orest Kiprensky, Alexei Venetsianov, Alexander Ivanov, Pavel Fedotov, Ilya Repin, Vasily Surikov, Valentin Serov and Mikhail Vrubel – to all of whom the present author has paid special attention in this book, and for one particular reason. Both the Russian avantgarde and ancient Russian icon-painting are well known and highly appreciated in Europe and America; our nineteenth-century painters, however, are virtually unknown outside Russia, and yet they undoubtedly deserve a place in the annals of world art.

The artistic ‘superpowers’ long ago agreed upon a hierarchy of excellence, in which nineteenth-century Russian art appears to have no place. Let us hope that this injustice will be gradually remedied. If the present book contributes in some small way towards that end, the author will feel that his mission has been fulfilled.

Sample pages

Download link (pdf; yandexdisk; 60.8 MB)

The electronic version of this edition is published only for scientific, educational or cultural purposes under the terms of fair use. Any commercial use is prohibited. If you have any claims about copyright, please send a letter to 42@tehne.com.

15 ноября 2024, 13:42

0 комментариев

|

Партнёры

|

Комментарии

Добавить комментарий