|

|

European Furniture in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. — New York ; New Haven and London, 2006  European Furniture in The Metropolitan Museum of Art: Highlights of the Collection / Daniëlle O. Kisluk-Grosheide, Wolfram Koeppe, William Rieder ; Photography by Joseph Coscia, Jr. — New York : The Metropolitan Museum of Art ; New Haven and London : Yale University Press, 2006. — ISBN 1-58839-178-7 (The Metropolitan Museum of Art) ; ISBN 0-300-10484-7 (Yale University Press)

This beautifully produced volume is the first to survey the Metropolitan Museum's world-renowned collection of European furniture. One hundred and three superb examples from the Museum's vast holdings are featured. They originated in workshops in England, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Austria, Russia, or Spain and date from the Renaissance to the late nineteenth century. A number of them belonged to such important historical figures as Pope Urban VIII, Louis XIV, Madame de Pompadour, and Napoleon. The selection includes chairs, tables, beds, cabinets, commodes, settees and sofas, bookcases and standing shelves, desks, fire screens, athéniennes, coffers, chests, mirrors and frames, showcases, and lighting equipment. There is also one purely decorative piece, a superb vase made for a Russian noble family who, according to one awestruck viewer, "owned all the malachite mines in the world." The makers of some of the objects are unknown, but most of the pieces can be identified by label, documentation, or style as the work of an outstanding European designer-craftsman, such as André-Charles Boulle, Thomas Chippendale, David Roentgen, or Karl Friedrich Schinkel.

Museum curators Daniëlle O. Kisluk-Grosheide, Wolfram Koeppe, and William Rieder discuss the history and significance of these objects, incorporating information gleaned from new research and conservation studies. The most important techniques of furniture making and decoration are also described—veneering, marquetry, joining, gilding, and inlay, among others—and a glossary offers additional information on these and many additional aspects of the craft. In the introduction, Danielle O. Kisluk-Grosheide discusses the history of the Museum’s collection. Her entertaining essay is accompanied by historical photographs from the Museum’s files and views of several of the Museum’s period rooms.

Photographs in color and black and white of the featured pieces, including full views and many details, were made expressly for this book by Joseph Coscia, Jr., Associate Chief Photographer at the Museum. Three hundred fifty-eight additional color images can be accessed on a CD-ROM disk in a sleeve at the back of the book. Many of them disclose hidden or hard-to-see aspects of the furniture, such as makers’ marks, details of construction and finishing, and secret drawers. Others offer closed and partially open views of folding and multifunctional furniture. In addition, close-ups and zoom shots of intricate inlay, sparkling gilt-bronze and silver mounts, and richly textured upholstery are featured.

292 pages, 134 color photographs, 115 black-and-white details of the objects and comparative illustrations. Bibliography, glossary, index, CD-ROM (with 358 color images and captions).

Foreword

Visitors to the European Sculpture and Decorative Arts galleries and period rooms at The Metropolitan Museum of Art enjoy one of the finest collections of European furniture in the world. The curatorial staff of the department as well as outside specialists research and regularly write about these objects in essays for scholarly journals and exhibition catalogues, and the new information reaches the general public by way of wall labels, websites, and audio tours. Yet neither the collection as a whole nor a selection of its most interesting pieces has ever been the subject of a significant publication.

This eagerly awaited volume presents 103 superb pieces of furniture. Every aspect of these Museum objects is examined, from their craftsmanship to their collection history. The works are of many types and styles, but all were chosen for their exceptionally high level of quality. Most are of French, English, German, or Italian origin, reflecting major areas of departmental strength, but there are more than a few outstanding examples from other countries as well. They range in date from the Renaissance, through the collection’s high point in the eighteenth century, to the last quarter of the nineteenth century.

The three authors of this volume—Daniëlle O. Kisluk-Grosheide, Wolfram Koeppe, and William Rieder—have long experience of this collection, as their numerous publications listed in the bibliography attest. All three began their careers at the Museum during the time when James Parker, who died in 2001 and to whom this volume is dedicated, was the principal curator of furniture in the department.

It is a pleasure to recognize the role played in the genesis of this book by my predecessor, Olga Raggio. She supervised the acquisition of many of the objects discussed here, and her expertise was a valuable resource for the authors. In the field of decorative arts, curators work closely with conservators and scientists. The contributions of members of the Departments of Objects Conservation and Scientific Research are gratefully acknowledged. New photography is an important element of this book. Joseph Coscia, Jr.’s images reveal to the reader not only the beauty of the furniture but also the intricacies of each piece’s fabrication. Multiple views and details are an invaluable aid to comprehending furniture’s many aspects. Accordingly, a CD-ROM of supplementary images has been added to this volume—for the first time in a Museum publication. None of this would have been possible without the approval of Director Philippe de Montebello, whose insistence on excellence set the standard for this as for all projects in the Museum.

As the introductory chapter documents, the Metropolitan’s European furniture collection reflects the taste and generosity of a number of private collectors, beginning a century ago. One of the guiding lights of its formation and enrichment, Mrs. Charles Wrightsman, remains an inspiration to and active supporter of the department. Through the Friends of European Sculpture and Decorative Arts, under the presidency of Frank R. Richardson, she and a number of other collectors generously subsidized some expenses of this publication. Another “Friend,” Andrew Augenblick, made an additional gift. The authors and the department are grateful to all of these supporters for making possible the publication of this splendid and timely book, which we hope will be the first in a series on the departmental collections.

Ian Wardropper

Iris and B. Gerald Cantor Chairman,

European Sculpture and Decorative Arts

Contents

Foreword ... vi

Acknowledgments ... vii

Notes to the Reader ... viii

A Brief History of the Collection by Daniëlle O. Kisluk-Grosheide ... 2

Highlights of the Collection by Daniëlle O. Kisluk-Grosheide, Wolfram Koeppe, and William Rieder ... 7

Glossary by Rose Whitebill ... 247

Bibliography ... 250

Index ... 269

Photograph Credits ... 283

Sample pages and photos

Armchair (fauteuil à la reine)

1779

Jacques Gondouin

Although intended to furnish Marie-Antoinette’s grand cabinet intérieur at the château de Versailles during the winter months, the chair and the rest of the set were removed in 1783, when the grand cabinet intérieur was redecorated and placed in the queen’s billiard room on the floor above. Sold during the French Revolution, the entire set of furniture was acquired by the American statesman Gouverneur Morris, who served as minister of the United States in France from 1792 to 1794. The pieces were subsequently sent to Morrisania, Morris’s country estate in the Bronx.

Set of fourteen side chairs

ca. 1772

Robert Adam British, Scottish

Chippendale executed this set of Neoclassical mahogany dining chairs for Goldsborough Hall, in Yorkshire, which belonged to Daniel Lascelles, younger brother of Chippendale's most extravagant patron, Edwin Lascelles, of nearby Harewood House. The set, which originally included fifteen chairs, remained at Goldsborough until 1929, when it was removed to Harewood House, from whence it was sold in 1976. The chairs represent one of Chippendale's most elegant designs: their tapering backs have arched top rails and molded sides headed by beaded paterae and leaf finials; fan-shaped splats with a central patera are encircled and flanked by pendent bellflower swags; and the square, tapering paneled legs are decorated with pendent husks. He produced several sets of these chairs with minor variations, including one, which has not survived, for Lansdowne House, in London. The present set, which has been reupholstered as it was originally with red morocco leather, re-creates in the Museum's dining room from Lansdowne House the

unity of design between the furniture and Robert Adam's decoration, which was one of the most notable aspects of this great Neoclassical interior.

Pair of side chairs

ca. 1724–36

Attributed to Thomas How British

The set included twelve side chairs, two settees, and two pedestals supplied to Nicholas, fourth Earl of Scarsdale (d. 1736) for Sutton Scarsdale, Derbyshire.

Side chair (one of a pair)

ca. 1755–60

After a design by Thomas Chippendale British

The design is based on one of several "ribband back chairs" in the first edition of Thomas Chippendale's influential patternbook The Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker's Director (1754).

Armchair (one of four)

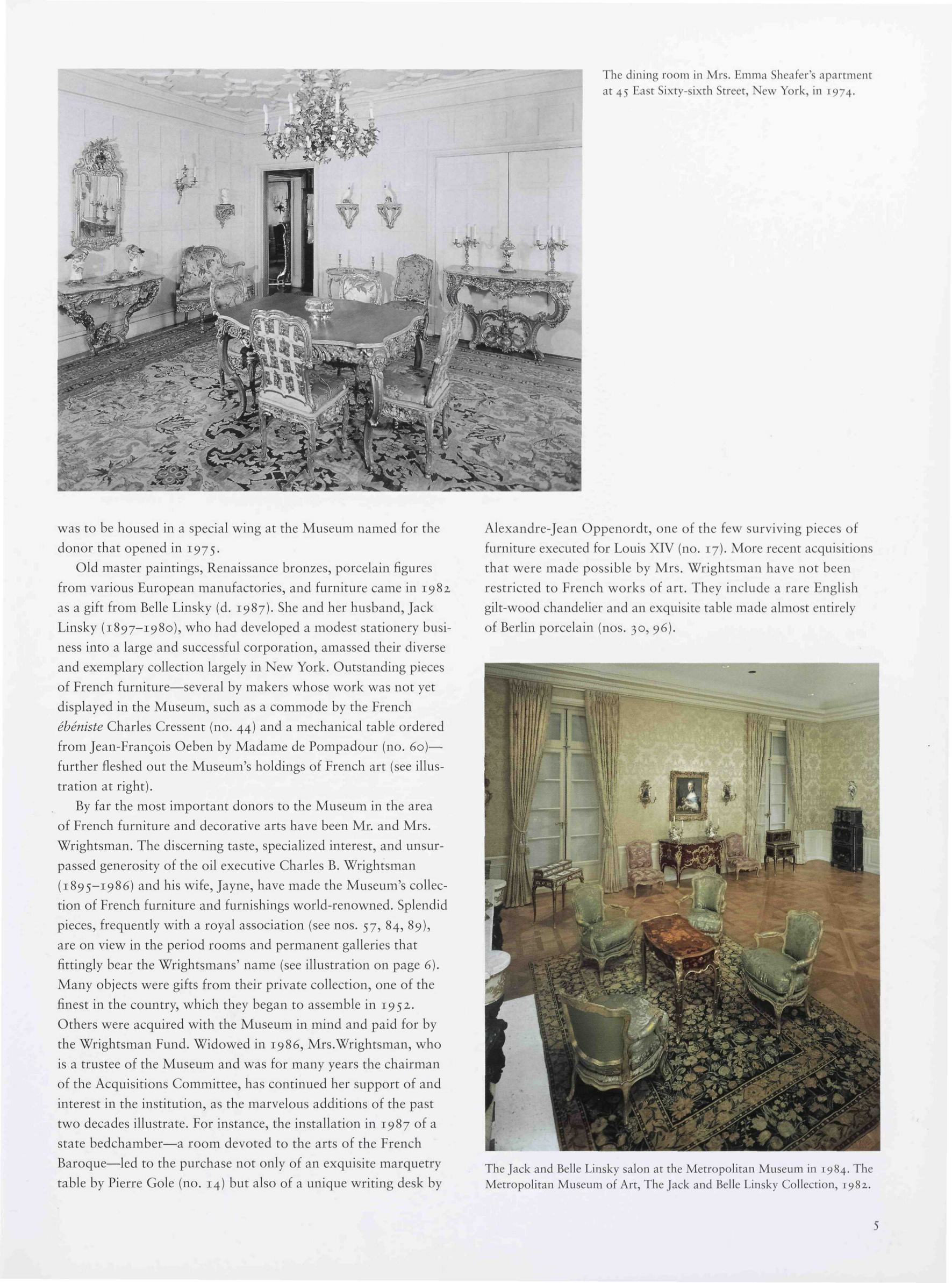

1755–65

Tapestry probably woven at Royal Manufactory Beauvais 1664-1789

This rococo chair is part of a larger set of seat furniture supplied to the third Duke of Ancaster (1714–1778) for Grimsthorpe Castle, Lincolnshire. Executed in the French taste, fashionable in mid-eighteenth century England, the set was originally partly gilt and upholstered with Gobelins tapestry (now in the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam) after designs by the painter François Boucher. The present covers were applied between 1934 and 1958.

Chandelier

ca. 1710–15

Attributed to John Gumley British

This is one of a pair of chandeliers commissioned about 1710 by James, third Viscount Scudamore (1684–1716), for the state apartments at Holme Lacy, Herefordshire. They may have been ordered to celebrate his marriage in 1710. In the richly decorated Baroque plasterwork of the saloon and dining room where they were hung, the chandeliers were a particularly harmonious addition. Holme Lacy later descended to the earls of Chesterfield; it was sold in 1910 by the tenth earl, who in 1917 moved many of the contents to Beningbrough Hall, North Yorkshire, where the chandeliers remained until 1958.

With its eight acanthus-scroll branches, its lambrequined octagonal stem, and its gilt-metal mounts in the form of feather-plumed masks, the chandelier is in the French "arabesque" manner of William III's architect Daniel Marot (1661-1752), who included designs for similar chandeliers in his Nouveau livre d'orfèvrerie, a pattern book for goldsmiths.

They are attributed on stylistic grounds to the court cabinetmakers James Moore and John Gumley, who specialized in finely carved gilt-gesso furniture. A closely related pair of chandeliers was commissioned from Moore and Gumley by King George I (1660–1727) for Kensington Palace.

Settee

ca. 1730

Possibly made by Benjamin Goodison British

This piece is from a large set of at least eight side chairs, four settees, four stools, and two side tables formerly attributed to James Moore (ca. 1670–1726) and said to have been made for Stowe, Buckinghamshire, a provenance now questioned.

Small desk with folding top (bureau brisé)

ca. 1685

Marquetry by Alexandre-Jean Oppenordt Dutch

This desk and its pair were supplied in 1685 for use by Louis XIV in his study, or petit cabinet, in the north wing of the château de Versailles. The form is called a bureau brisé, literally a "broken desk," because the hinged front half of the flat top can be folded back, or "broken," to reveal a narrow writing surface. The elaborate decoration on top includes the king's crowned monogram of interlaced L's beneath a radiant sun symbol engraved with a now indistinct Apollo mask.

Small writing desk (bonheur-du-jour)

ca. 1768

Martin Carlin French

Madame du Barry (née Jeanne Bécu; 1743–1793) became the official mistress of Louis XV after the death of Madame de Pompadour. In 1770 she was described in less than favorable terms by Elizabeth Seymour Percy, Duchess of Northumberland (1716–1776): "She is rather of a tall, middle size, full breasted, and is pretty but not to be call’d handsome . . . & has a strong Look of her former profession. Her Complexion is fair & clear & her skin very smooth but her Bloom is entirely gone off. . . . She is lodged in parts of the Kings apartment in the Attic."[1] Madame du Barry bought luxury furnishings from the dealer Simon-Philippe Poirier for those private rooms at Versailles, including a small writing table with a raised section at the back, on November 18, 1768. It was recorded in her apartment at the palace, which she occupied until a few days before the king’s death, in May 1774, and described as “a very pretty stepped table with French porcelain on a green ground with floral cartouches.” Quite possibly the Museum’s bonheur-du-jour, as this type of small writing desk is called, was the one formerly in the possession of the king’s favorite. The model was repeated a number of times, and today eleven such bonheurs-dujour are known, but this is the only one that can be dated to 1768, based on the date letter P for that year painted on the back of twelve of the porcelain plaques. The desk has been attributed to Martin Carlin, who made some eighty pieces of porcelainmounted furniture between 1765 and 1778, intended for a fashionable and distinguished clientele consisting mostly of aristocratic ladies. Carlin supplied furniture to Poirier and later to his partner and successor, Dominique Daguerre (d. 1796 ), who were the principal buyers of porcelain plaques at the Sevres manufactory. Supported on four slender cabriole legs, this small piece is fitted with a single drawer in the frieze of the lower section, which has a hinged writing surface as well as a compartment that used to hold an inkwell, a trough for a sponge, and a box for sand to blot up excess ink.

Table

ca. 1660

Attributed to Pierre Gole

When it was sold from Mentmore Towers, Buckinghamshire, in 1977, this exceptional table was described as in the manner of Leonardo van der Vinne. A talented artist of Flemish or Dutch origin, Van der Vinne made marquetry furniture at the Medici court in Florence during the second half of the seventeenth century. In the mid-1980s, however, the table was reattributed to Pierre Gole, based on documentary evidence and after comparison with a few extant pieces thought to be by the same hand.

Commode

ca. 1745–49

Charles Cressent French

One of a group of six known commodes of this model, it shows the cabinetmaker (ébéniste) Charles Cressent’s highly individual and very sculptural manner. Although Cressent did not sign a single piece of furniture, a considerable body of work has been attributed to him. This commode with its unusual shape matches a detailed description in the 1749 sale catalogue for one of the three auctions that Cressent, when pressed by financial difficulties, organized of his own stock and art collections.

Supported on four tall legs, the front of the commode contains two drawers and each of the sides has a single door opening to a cupboard. The undulating outline of the front and sides is repeated in the marble top while the carcass is entirely covered with marquetry veneer in a fine geometric pattern known as parquetry. Particularly noteworthy are the bold and highly decorative gilt-bronze mounts which are so distinctive of Cressent’s work: Zephyr heads, large scrolling acanthus leaves and, most characteristic, a charming scene of two boys who swing a monkey on a knotted rope. These inventive gilded bronzes are clearly foreshadowed in the outline of the amaranth veneer, creating a marvelous harmony of design.

Drop-front desk (secrétaire à abattant or secrétaire en cabinet)

ca. 1776

Attributed to Martin Carlin French

Attributed to the cabinetmaker Martin Carlin, who was known for his graceful furniture mounted with Sevres porcelain, this exquisite two-piece desk was made about 1776. A date letter for that year is painted on the back of the central porcelain plaque, together with the mark of Edme-Francois Bouillat (1739/40–1810), a painter at the Sevres manufactory. A specialist in different kinds of floral ornament, Bouillat decorated the main plaque with a flower basket suspended from a large bowknot. The history of this secretary is well documented. During the eighteenth century it graced the collections of two remarkably different women. Its first owner was the popular soprano Marie-Josephine Laguerre (1755–1783), who as a fille d'Opera enjoyed a luxurious and dissolute existence made possible by her wealthy lovers. Her personal property was publicly sold in April 1782, less than a year before her untimely death. The catalogue indicates that she owned this secretary as well as two other pieces of furniture embellished with porcelain plaques. Some of the Sevres decorative wares in her collection may have been displayed on the marble shelves of the secretary. It is likely that Dominique Daguerre, who with his partner, Simon-Philippe Poirier, had a virtual monopoly on the purchase of Sèvres plaques, supplied the piece of furniture to Laguerre and bought it back at the 1782 sale, but this is not documented. In May of that same year, Maria Feodorovna, grand duchess of Russia, and her husband, Paul (1754–1801), visited Paris incognito as the comte and comtesse du Nord. The future empress was described by Jeanne-Louise-Henriette Campan (1752–1822), first lady-in-waiting to Marie-Antoinette, as being “of a fine height, very fat for her age, with all the stiffness of the German demeanour.” In Paris, Maria Feodorovna frequented the shops of the fashionable dealers, where she is likely to have acquired the porcelain-mounted secretary and other furnishings for her country residence at Pavlovsk.

According to a detailed description of her private rooms written in 1795 by Maria Feodorovna herself, the secretary was placed in her boudoir. It remained at the imperial palace until the Soviet government, which had taken possession of Pavlovsk after the Revolution of 1917, offered works of art for sale to the dealer Joseph Duveen (1869–1939), who had traveled to the Soviet Union in 1931.

Cabinet

1867

Designed by Jean Brandely French

When the prototype for this compelling cabinet, now in the collection of the Musée d'Orsay, Paris, was exhibited at the Exposition Universelle in 1867, it received mixed criticism. The cabinetmaker must have been pleased with the controversial piece because he commissioned this second, nearly identical one for himself. The central plaque by the sculptor Emmanuel Frémiet commemorates the military triumph of Merovech (d. 458), leader of the Salian Franks, over Attila and his marauding Huns at the Battle of the Catalaunian Field in 451. In a vivid and unsettling representation, Merovech stands before his troops at the front of the chariot as it passes over the dead body of an opponent.

Mirror

ca. 1710

Johann Valentin Gevers German

This sumptuous mirror beautifully evokes the wealth of silver furnishings at the Versailles of Louis XIV (1638–1715) and, to a lesser extent, at other European Baroque palaces. Well documented in contemporary descriptions, the 167 pieces of silver furniture in Louis's state rooms, as counted by a Swedish architect, Nicodemus Tessin the Younger (1654–1728), were mostly made at the Manufacture Royale des Meubles de la Couronne at the Hôtel des Gobelins, in Paris. Symbolizing the glory and magnificence of the Sun King, this opulent furniture astonished and dazzled all who saw it. Foreign rulers sought to emulate the example set by Louis, and long after his silver furniture had been melted down to pay for his military campaigns, similar costly pieces were still ordered for the state apartments of princely and other aristocratic residences all over Europe.

One of the most important centers for working precious metals was the German city of Augsburg, and many of the pieces of silver furniture known today originated there. Unlike the furnishings executed for Louis XIV, which were nearly all made of solid silver, the objects executed in Augsburg consisted of a wooden core covered by thin silver plates. Augsburg silversmiths also supplied silver and silver-gilt mounts for the embellishment of luxurious objects veneered with tortoiseshell and tinted ivory, such as the Museum's mirror.

The pronounced geometric projections of the mirror's colorful frame are typical of the South German Baroque. The feature seems to have been particularly fashionable in Augsburg, as is seen in the stepped stands of clock cases, altars, and cabinets that were also executed there. The elaborate silver and silver-gilt mounts, however, rendered in a strictly symmetrical manner, are French in character. The volutes, bandwork, acanthus foliage, tasseled lambrequin motifs, fruit and flower baskets, birds, masks, and drapery ornament appear to have been inspired by the designs of the influential French architect Jean Bérain (1638/39–1711). Bérain's decorative style was disseminated abroad by Huguenot craftsmen who left France in 1685 after the revocation of the Edict of Nantes. Jeremias Wolff (1663/73–1724) and other Augsburg publishers sold pirated copies of Bérain's designs during the late seventeenth century and early eighteenth century. In addition, many German silversmiths had spent several years of training abroad, often in Paris, and foreign journeymen came to work in Augsburg, stimulating the exchange of ideas and adoption of new styles.

Standing shelf (one of a pair)

ca. 1753–54

William Linnell

Supplied to the fourth Duke of Beaufort (1709-1756), the set of japanned furniture for the Chinese Bedroom at Badminton House, Gloucestershire, included a bed, eight armchairs, two pairs of standing shelves, and a dressing commode.

Settee

ca. 1885

Designed by Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema British, born The Netherlands

Part of a set of furniture designed for the music room in the New York residence of Henry G. Marquand on Madison Avenue at Sixty-eighth Street. Marquand was one of the founders of the Metropolitan Museum and its president from 1890 until 1902. The upholstery is modern: silkscreened designs were specially commissioned in an attempt to evoke the original richly embroidered panels of the settee's seat and back.

Side chair (one of a pair)

ca. 1815–20

Circle of Josef Danhauser

The years between 1815 and 1848 in Germany and Austria were characterized by a conservative political and cultural climate. The period and its style of interior decoration are both called Biedermeier, after a fictional character invented by the poet Ludwig Eichrodt (1827–1892) in the 1850s. Although the term invokes qualities typical of the German bourgeoisie (unpretentiousness, thrift, domesticity), the origin of the Biedermeier furniture style was totally aristocratic. The simple, elegant forms with their clean lines and light-colored wood veneer derived from the ornamentally restrained furniture that had been made for the royal and princely households of Germany, Austria, and France beginning in the late eighteenth century. For this market, even Parisian ébénistes, such as Canabas, Saunier, Jacob, and Molitor, produced simple mahogany pieces that were set apart only by their excellent materials and outstanding craftsmanship. Berlin, Munich, and Viennese cabinetmakers followed suit, creating similar, refined furniture.

Contemporary watercolors document that Biedermeier interiors were characterized by the use of strong colors for paint, wallpaper, and fabrics. Consequently, the upholstery specialist of the Metropolitan Museum's Objects Conservation Department was delighted but not surprised to discover some silk threads of a strong aquamarine color beneath the former show covers on the present chair and its pair, which is also in the Museum's collection. An appropriate fabric was acquired and dyed to match these remnants of the earliest upholstery. Seldom are curators and conservators given such a splendid opportunity to recreate the original appearance of a piece of furniture and to do it with the correct material, in this case, precious silk. The spring upholstery on the drop-on seats is original, as are large parts of the surface finish. The quest for truly comfortable seating furniture characterized the Biedermeier period: in 1822 Georg Junigl obtained a patent in Vienna "for his improvement on contemporary methods of furniture upholstery which, by means of a special preparation of hemp and with the assistance of iron springs, he renders so elastic that it is not inferior to horsehair upholstery."

The Museum's side chairs, originally part of a set of six, can be attributed to the firm of Josef Ulrich Danhauser (1780–1829), the leading furniture manufacturer in Vienna. He had many royal patrons, including Archduke Karl von Sachsen Teschen (1771–1847) and Duke Albert von Sachsen Teschen (1738–1822). The Danhauser factory produced some items in large quantities, and these pieces established the firm's reputation throughout Central Europe and Northern Italy.

Armchair (fauteuil à la reine)

ca. 1690–1710

French, Paris

In the most recent catalogue of the furniture at Versailles, where two related armchairs à châssis (with drop-in seats) are on display in the refurbished bedroom of Louis XIV, this extraordinary chair model was described as "to be dated probably to the second quarter of the eighteenth century." This proposed dating was based on "the setting back of the armrest supports" and "the absence of a stretcher" between the legs. The chair's overall appearance, however, as well as the Italianate, trapezoidal form of the seat make an earlier date much more plausible. Also, the ornamentation and the minimally curved, rather straight-looking arms with their stylized-volute "hand knobs" betray the pervasive influence of Charles Le Brun (1619–1690), director of the royal manufactory at the Gobelins and of the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture (since 1663) under Louis XIV. Le Brun's playfully arranged designs are echoed in many decorative works of the late seventeenth century, for example, four embroidered wall hangings of about 1685 and an ingeniously designed side table of about 1690, both in the collection of the Museum.

Traveling table (table de voyage or table pliante)

ca. 1700–1720

French

The Château de Saint-Cloud, near Paris, belonged to the ducs d'Orléans until 1785. In the estate inventory of the furnishings in the rooms of Duchesse Élisabeth Charlotte (1652–1722), called Madame, sister-in-law of Louis XIV, there is mentioned a carved writing desk made of walnut on pieds de biche (doe's feet). The French term could be taken literally, because zoomorphic feet for furniture was a very fashionable conceit in the seventeenth century. But the term could also refer to the slim, stylized S-curved legs of late Louis XIV and early Régence style that suggest the sweetly elegant stance of the deer. This leg shape, seen also on the Museum's table, appeared about 1700 at the latest-certainly not in the Rococo period, as has long been maintained.

This refined and ingeniously constructed table is a very rare example of a type of multifunctional furniture that was specifically invented for rough and space-limited journeying via coach. Before the advent of the automobile, a traveler could not count on finding the comforts of home at a place where he found himself benighted or stranded by unforeseen events, such as a broken axle-a misfortune that occurred often on unpaved roads.

Cabinet

ca. 1655–59, engraved decorations ca. 1825–50

Cabinetry by the workshop of Melchior Baumgartner German

During the sixteenth century, collecting rare, beautiful, and valuable objects became a fashionable pursuit among the princes and wealthiest citizens of the Holy Roman Empire. Many of their palaces contained a room called a Kunstkammer or a Kunst- und Wunderkammer (chamber for artworks and curiosities). Here the treasures were displayed, frequently in a sequence of interconnected spaces dedicated to various fields of collecting. The three principal categories were naturalia (products of nature), artificialia or artefacta (products of the human hand), and scientifica (scientific instruments, such as astrolabes and clocks). The intention was to suggest the wealth and learning of the collector and to impress foreign guests.

Some collectors of small objects commissioned elaborate cabinets decorated with semiprecious stones or exotic woods, such as ebony, or other sumptuous material. These pieces were furnished with many drawers and secret compartments, which offered diverse storage opportunities. Some were designed to stand against a wall in the company of other display cases. Others stood independently, like the Metropolitan's example, which is finished on all sides; this type of cabinet could be said to represent in miniature format an entire Kunstkammer, which was itself a metaphor for the known world in all its diversity.

The Museum's cabinet is completely encased in ivory and has only a few gilded yellow-metal mounts that are essential for its use, such as the auricular-style handle on each side and the key plates. The many wooden moldings—on the attic story and the base, as well as around the vertical panels on the facade—are decorated with a ripple pattern and gilded. During the day these would reflect the incoming sunlight, but at night the myriad silver notches would catch and intensify every flickering ray of the candles, giving a satin-like sheen to the smooth ivory panels. This river of silver ripples must always have drawn viewers, like bedazzled moths, to a closer inspection of the piece.

Exotic ivory, purchased by the ounce like silver or gold, was prized for its creamy white, fine-grained surface, which was frequently compared to a woman's skin and for that reason, perhaps, often used for implements and requisites of the toilette. Since the Middle Ages such items were stored in ivory-decorated boxes, some of the finest examples of which were made at the Embriachi workshop in Venice.

The decoration engraved on the ivory veneer—large figures representing Wisdom (left side), Strength and Tolerance (front), and Knowledge (right side)[4] and a wealth of abstract and naturalistic ornaments—were probably applied in the second quarter of the nineteenth century in England. That the original intention had been to make a strong contrast between a grand but plain exterior and a dazzling display concealed behind the cabinet's doors was not taken into consideration. The style of the engravings, especially the rocaille-like formations in the corners of the doors and the clumsily stylized Tudor rose on the top, is typical of the nineteenth-century taste for reviving earlier stylistic forms and combining them haphazardly.

The front opens to reveal a pyrotechnical sparkle of silver and partly gilded applications. There are three figural silver plaques, three richly carved architectural structures, and many drawer fronts, each decorated with ornamental pressed silver foil. The central plaque, framed within a columned aedicula, conceals a door to a compartment that is veneered on all sides with ebony, ivory, and other exotic woods in a four-pointed-star pattern. The back wall can be removed to access ten drawers of different sizes. A toilette mirror is contained in the drawer below. In the large base drawer of the cabinet there is a tablet inlaid with ivory and exotic woods. This could be used for writing or gaming. An inkwell, a sander, and gaming pieces could be stored here in drawers with a sliding top. The tablet could also serve as a tray to display precious objects ordinarily hidden away in the drawers. The attic story is fronted by doors concealing a nest of drawers, and there are drawers in the sides of the top as well.

Mirror

ca. 1680–1700

German, Danzig (Gdansk)

Large parade mirrors became increasingly fashionable throughout Europe during the Baroque period, and they were often conceived as part of an ensemble, with matching console tables and candlestands. This development was supported by technical advances that made it possible to produce larger plates of mirror glass and driven by the ambition of princes to imitate the magnificent Galerie des Glaces in the suite of state rooms at Versailles, created in 1681-84 by Charles Le Brun (1619–1690) for Louis XIV of France.

At the end of the seventeenth century, goods and artistic ideas flowed through northeastern Europe along trade routes that connected English and Netherlandish ports with the cities along the Baltic Sea and points east. The latest fashions were eagerly received and copied as closely as local craftsmen could manage and local patrons could afford. This mirror was once believed to be of Dutch origin, but its putti nestled among a tangle of jaggedly lobed acanthus leaves have proved to be very similar to works in wood by the cabinetmakers and virtuoso carvers of the independent town of Danzig, one of the most prosperous trade centers on the Baltic seacoast and a gateway to Russia. Large quantities of household goods, such as Dutch case furniture and English chairs, were imported into Danzig during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, as were luxury items like the popular Chinese blue-and-white porcelains. The grotesque dragon-monsters on this mirror, with their intriguingly intertwined necks and long tails, were obviously inspired by the decorations on the porcelain exported from East Asia. Dragons have been part of both Eastern and Western imagery for millennia, but seventeenth-century European craftsmen were probably unaware of their symbolism as water deities in the East and of Satan in the West.

This frame offers an ingenious combination of decorations from both traditions. The elements of chinoiserie are dominated by the acanthus-leaf ornament, however, which was especially popular in Europe at just the time this mirror was made. The plant's twisting and luxuriant pattern of growth fulfilled the Baroque period's desire for ornate and extravagant ornamentation. The acanthus designs by the French engraver Jean Le Pautre (1618–1682) and by his follower Paul Androuet Ducerceau (1630–1710) were adapted and exaggerated by such ornamentists in the German-speaking world as the Viennese court cabinetmaker Johann Indau (1651–1690) and the Augsburg masters Johann Unselt and Johann Conrad Reuttimann. In Bohemia and parts of Silesia, acanthus decoration was taken to an unprecedented extreme in the altarpieces called Akanthusaltäre. These were conceived in the pure spirit of ornamental fantasy, as the rioting vegetation completely conceals the function of the objects it decorated. In the entrance and banquet halls of grand town houses the acanthus crept across chairs, tables, and large armoires and up staircases and along wall paneling; in the form of stucco ornament it also decorated ceilings. The result was an impressive decorative unity that transmitted a feeling of lushness and prosperity, which reflected the owner's social status.

Rolltop desk

ca. 1776–79

David Roentgen German

This splendid rolltop desk is distinguished by having six legs instead of the usual four. The added pair and the lavish mounts changed the frontal view into a more facadelike structure. The presence of the mounts and the use of exotic marquetry woods point to an affluent patron. Even so, it is not the most elaborate desk designed by David Roentgen during this period. Traditionally, however, it is considered a preeminent example of his technical skill and artistic creativity. The monogram DR inlaid on the drawer above the kneehole indicates the cabinetmaker’s satisfaction with what he must have considered an exceptionally refined desk, as access to its inner secrets can be gained only via the keyhole above his initials.

When the key is turned to the right, the compartment to the right of the kneehole slides forward. A button underneath can be pressed to release its front half. This swings aside to reveal two drawer panels, each with four Birmingham Chippendale-style pulls. Not every pull is functional, however, for the compartment contains only two deep drawers, not four shallow ones. The veneer, which was cute from matching sheets, has a curtain-like look, even though the grain lines are broken by brass moldings. Pressing in and turning the key to the left opens the compartment to the left of the kneehole; pressing it in halfway and turning it to the left disengages the writing surface, which can then be pulled forward by means of the drop-loop handles; simultaneously, the curved top opens, revealing the interior. The rectangular structure above the rolltop consists of a single side drawer. It is crowned on three sides by a pierced gilt-bronze gallery chased on both the front and the reverse and decorated with gilt-bronze acanthus cones, ornaments that were favorited by the workshop during the entire neoclassical period. The sparkling ormolu and brass moldings have preserved some residue of their original gold-lacquered surface.

The colorful chinoiserie marquetry on the desk’s front and sides is set into large panels of maple wood, which may originally have been stained a shade of blue gray. In this case, a blue-gray background would have been exceptionally striking, for the visible grain of the maple would have evoked a steel-blue fabric that was popular in the late 1770s. Like a theater scrim, it would have set off the lively scenes of Chinese life, confining them within an apparently shallow, three dimensional space. The workshop used the vignettes on numerous pieces; they are based on drawings by Januarius Zick.

Armchair

ca. 1828

Karl Friedrich Schinkel German

Between 1826 and 1828, at the height of his influence as Germany's leading architect and most sought-after designer, Karl Friedrich Schinkel was commissioned by Prince Karl of Prussia (1801-1883) to remodel the prince's Berlin palace (destroyed in World War II). It seemed appropriate that Karl, a son of King Frederick William III of Prussia (1770–1840) and the younger brother of King Frederick William IV (1795–1861) and Emperor William I (1797–1888), would engage the court architect Schinkel to draw up the plans. For the Marble Hall (or Reception Hall) Schinkel designed a luxurious suite of gilded furniture, comprising two sofas and eight armchairs, one of which is the present piece. Many of the details reflect the designer's sensitivity to all aspects of the room's decor. One of the most intriguing of these is the similarity between the sides of the sofas and the pattern of the inlaid border of the wooden floor. Like most display furniture, all ten pieces would have been placed against a wall. The details of the show covers and the ornaments on the front, such as the sphinxes looking forward from the arm supports and the lion mascarons on the armrests, give the furniture a ponderous grandeur; however, the chairs, which are indeed extremely heavy, have casters and can be moved-belying their monumentality and very much to the astonishment of the viewer, who can thus appreciate them from all sides.

Until recently there was much confusion as to how many examples of the chairs of the former suite were still in existence. The situation is now thought to be as follows. The Stiftung Preussische Schlösser und Gärten Berlin-Brandenburg currently displays two chairs in the Schinkel Pavilion at Schloss Charlottenberg, Berlin, and there is a further example in storage at Schloss Charlottenburg. The Kunstgewerbemuseum in Berlin owns two chairs, and there is another example, which has possibly retained much of its original upholstery under a later show cover, in the Danske Kunstindustrimuseum in Copenhagen. Therefore, it seems that seven chairs (including the Museum's piece) have survived, leaving one example as well as the pair of sofas unaccounted for.

It is generally acknowledged that the Museum's chair is the prototype for the series and was made under the architect's supervision. It retains most of its original gilding and the original casters, and, in addition, the decorative parts, such as the fully three-dimensional sphinxes and the flat relief ornamentation, are carved in wood following traditional chairmaking techniques. Molds were later made of these elements in lead, zinc, iron, and composite mass in order that casts might be applied to the other pieces in the suite. As the chair prototype was one of the most expensive ever produced, this was clearly done in order to simplify production and reduce costs. The use of different materials for the decorative parts of the later chairs reflects Schinkel's passion for exploring new production methods.

Schinkel's design for the prototype is based on an ancient Roman chair depicted in wall paintings that had been excavated in Herculaneum in the eighteenth century. The sketch of a related but bolder chair in the Egyptian taste appears in plate 29 of Charles Percier and Pierre-François-Léonard Fontaine's Recueil de décorations intérieures, of 1801. A closer comparison, however, is provided by plate 59, fig. 1, in Thomas Hope's Household Furniture and Interior Decoration, of 1807, a publication well known to the German architect. Hope's and Schinkel's interpretations clearly follow the ancient paintings, even to the extravagantly conceived but structurally weak armrests. If Schinkel's chairs are picked up by the arms rather than moved on their casters, the thin armrests and their fragile supports may break. A regilding of the repaired areas is then inevitable. This must have happened to the Museum's example before it was acquired.

Cassone with painted front panel depicting the Conquest of Trebizond

after ca. 1461

Attributed to workshop of Apollonio di Giovanni di Tomaso Italian

This impressive marriage chest is said to have come from the Palazzo Strozzi, and it has the Strozzi emblem of a flacon perched on a caltrop (a spiky metal weapon) with a banderole inscribed ME[Z]ZE—probably a reference to the half-moons in their armorial device. The form of the cassone evokes classical sarcophagi. The painted front does not belong to this chest but is contemporary with it. It shows a battle before the city of Trebizond; Constantinople is seen at the upper left. In the foreground is a battle between Ottoman and Byzantine troops. Trebizond fell to the Ottomans in 1461, but the ruler seated beneath a canopy is identified as Tamerlane (ca. 1336–1405), the Mongolian emperor who defeated the Ottoman sultan at Ankara in 1402. These historical anachronisms have not been explained, but the advance of the Ottomans was something that preoccupied all of Europe—not least those with mercantile interests in the Middle East.

Chair (Sgabello)

ca. 1489–91

Attributed to the Workshop of Giuliano da Maiano (1432–1490) and Benedetto da Maiano (1442–1497)

The Strozzi chair is one of the best-known and most often published pieces of seating furniture in the world. Shortly after 1900, in a period when Italian Renaissance furniture was as highly prized as old-master paintings, Hans Stegmann called it a "unicum known the world over. . . a masterwork of charming beauty, one of the most beautiful Florentine pieces of furniture around." Given its celebrity, it is astonishing that the most recent publications on the chair rely on information in the 1930 catalogue of the collection of the Viennese banker Albert Figdor, who acquired it in the 1870s from Prince Strozzi in Florence, and ignore later investigations.

The form of the sgabello derives from a low stool with three legs (a tre gambe) mounted at an angle, a very simple type of seat that had been popular since ancient times. By adding an elongated backrest, the designer demonstrated unusual sensitivity to shape and ornament and a degree of subtlety that is rarely found in furniture. The decoration on the back, sides of the seat, and feet consists of delicately carved elements and a small line of geometric inlay. The latter is consciously contrasted with the dramatic veining of the walnut wood. The elegant concept and the attention given to minute details indicate that this was a very special commission for all the artisans involved.

The backrest seems comparable in silhouette to a peacock's feather. A plain center panel supports the tondo on top, in the "eye" of which the Strozzi coat of arms with three crescent moons (arme delle tre lune) and lavish acanthus decoration stand out against a punched background. Crowning this is the image of a molting falcon. In the background, feathers cascade down in a circular movement from the spread wings of the bird.

The three crescents within a shield can be seen again on the reverse of the tondo, in front of a fluted sun motif. The encircling band consists of four rosettes at the cardinal points connected by feathered scales arranged in divergent directions. The whole tondo-front and back-is framed by a wreath of crescent moons, another allusion to the house of Strozzi. Following Wilhelm von Bode, Frida Schottmüller remarked that the reverse of a medal made for Filippo di Matteo di Simone Strozzi (1428–1491), in the "manner of Niccolò Fiorentino," was used as the model for the front of the tondo. Other early writers ascribed the medal as well as the design of the sgabello to the workshop of Giuliano and Benedetto da Maiano. Both brothers were regularly employed by Strozzi. Documents show that in 1467 Filippo Strozzi ordered from Giuliano da Maiano a richly inlaid cassone for himself, as well as a lettuccio, or bench. The medal, which has now convincingly been attributed to Niccolò Fiorentino (1430–1514), was probably commissioned for the cornerstone ceremony at the Strozzi Palace, on 6 August 1489. It exists in multiple copies and could easily have been examined by other artisans.

Barberini Cabinet

ca. 1606–23

Galleria dei Lavori, Florence

The arms are those of a Barberini cardinal, probably Maffeo Barberini (1568–1644), who became Pope Urban VIII in 1623. The scenes from Aesop's Fables are after woodcut illustrations in the edition by Francisco Tuppo published in Naples in 1485.

Side chair (part of a set)

ca. 1790–1800

Italian, Sicily

The gilded moldings and carved decoration on this chair and a matching settee (acc. no. 1992.173.1) frame reverse-painted glass panels, which imitate in different colors the hardstones agate, marble, and lapis lazuli. Close inspection reveals the high quality and intriguingly delicate structure of the paint and the fragility of the panels, which is not evident at first glance. That the chair and settee have survived in such good condition is testimony to the technical skills of the maker, who provided a sound base for the heavy glass strips, preventing them from peeling away over time. Nevertheless, these are display pieces that were clearly not intended for regular use. The smallest body movement of a user or any attempt to shift or lift the heavy objects puts divergent forces and pressure on their ostentatious "skin."

The Museum's chair and settee are part of a large suite that originally consisted of at least four settees and twenty side chairs. Early in the twentieth century the set was in the collection of the earl of Derby, at Derby House, London, from where it was sold in 1940 to Mrs. Violet van der Elst, also of London. The pieces were dispersed in 1948. At that time, all items of the suite were covered with the bold red and gold baroque-cut velvet that still decorates the Museum's pieces. For many years it was assumed that the initials "PPL" displayed in a medallion on the backs referred to the Villa Palagonia in Bagheria, near Palermo, and, more specifically, to a member of the illustrious Gravina family as a patron; however, as James David Draper pointed out, although "the peculiarly Sicilian penchant for fashioning an overall look out of glass was most memorably given free rein at the Villa Palagonia, . . . the initials 'PPL' . . . do not correspond with those of any prince of Palagonia and in truth the pieces have a much more pronounced neo-classical severity than the Villa Palagonia ballroom."

John Richardson, the donor of the Museum's pieces, which he had acquired on the London art market, kept them at one point in the Château de Castille in Provence, the home of the Cubist scholar Douglas Cooper, who himself owned at least three chairs from the set. For the moment, the original location of the suite remains a mystery, although the preciousness and labor-intensive nature of the work narrows the source of the commission to one of the great, prosperous, aristocratic families of Sicily.

The back of the settee is tripartite; the medallion with initials appears at the top of the center section, but in the same place on the side sections there is a military trophy in the form of a helmet superimposed on a saber. There is a gilded openwork frieze of overlapping ellipses along the top of the back of both the chair and the settee; this appears also along the bottom of the back of the settee but not on the Museum's chair. These ellipses, rather freely adapted from ancient vase paintings, reflect the so-called Etruscan fashion of the last third of the eighteenth century. A very similar pair of chairs, each, however, with an octagonal verre églomisé panel set into the back in place of upholstery, is part of the collection of Juan March Ordinas at Palau March in Palma de Mallorca. That those panels show a mythological chariot in the manner of an ancient vase painting is also very much in the "Etruscan" style. The incorporation of glass panels in the center of the backs makes the March chairs even more fragile than the Derby House suite.

Center table

ca. 1780–85

Imperial Armory, Tula (south of Moscow), Russia

From 1712, when the imperial armory in the town of Tula, south of Moscow, was founded by Peter the Great (r. 1682–1725), the master armorers regularly enjoyed imperial patronage. During the reign of Empress Elizabeth (1741–61), they began to produce a sideline of cut-steel decorative items and furniture now known as Tula ware. These were richly and elaborately worked using many different techniques in addition to the faceting that gives them their characteristic diamond-like sparkle. Although in their shapes Tula chairs, tables, and stools resemble traditional wooden furniture, they are chased, blued, chiseled, gilded, pierced, and inlaid like parade weapons. They have come to embody for the eighteenth century the Russian decorative arts, as Fabergé objects have for the decades just before and after 1900. So greatly admired was Tula ware in Western Europe that around 1775 its steel-cut look was imitated in silver and silver-gilt by Augsburg goldsmiths.

In 1785 Empress Catherine the Great, during whose reign (1762–96) the Tula factory flourished, sent two of the armory's most experienced steelworkers to England in order to hone their skills and broaden their creative outlook and ideas; however, English pattern books such as Thomas Chippendale's The Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker's Director (1754) were already in circulation among Russian cabinetmakers. The most imaginative pieces of Tula furniture-objects like the Museum's table-were either delivered directly to Catherine the Great or purchased by her and her family or at the annual Sofia Spring Fair near the palace of Tsarskoye Selo. Made in a cooperative effort by designers and specialist craftsmen, such illustrious pieces were seen as objets d'art and were intended for display and not for daily use. So great was Catherine's passion for these fabulous objects that in 1775 she merged her Tula ware collection of several hundred pieces with some of the crown jewels and placed them together in a special jewelry gallery at the Winter Palace. The empress loved the reflection of light from the thousands of cut-steel facets that caught the rays of the sun by day and the flickering light of candles by night.

Hip-joint armchair (sillón de cadera or jamuga)

ca. 1480–1500

Spanish, Granada

This armchair consists of four S-shaped supports on two runner-like stands. The disks that join two of the supports at front and two at back suggest that the chair can be folded up like a pair of scissors. This is not possible, however. The supports will collide above the turning point, allowing only a small degree of movement. This impractical arrangement can easily be explained by the chair's derivation. It descends from the sella curulis, or curule chair, an ancient Roman folding seat used by consuls and high officials. In its elegant medieval interpretation, the throne-like chair—by then called a faldistorium—continued to symbolize secular power, and as the customary seat of the higher clergy, it also came to express the authority of the church. The folding mechanism was eventually eliminated, and the place where the joint had been was marked with an ornamented disk.

Commode

ca. 1710–20

André Charles Boulle French

In 1708, the prototypes for this commode, then called a pair of bureaux, were delivered to the Grand Trianon by André-Charles Boulle. The duc d'Antin, director of the king's buildings, wrote to Louis XIV: "I was at the Trianon inspecting the second writing desk by Boulle; it is as beautiful as the other and suits the room perfectly." Not until the Trianon inventory of 1729 were the pieces described as "commodes." (They are often called commodes Mazarines because they stood during the nineteenth century and the first third of the twentieth in the Bibliothèque Mazarine in Paris.) From the beginning, the design proved to be immensely popular, although it has also been criticized for an "awkward treatment of forms," meaning, in particular, the four extra spiral legs that were required to support the weight of the bronze mounts and marble top. Nevertheless, the Boulle workshop made at least five other examples of this expensive model, including the Metropolitan's. Traditionally, they have been dated between 1710 and 1732, the year of Boulle's death; by 1730, however, the decorative style of the Sun King's long reign had been supplanted by the lighter forms of the Régence and early Rococo, and a date of 1710–20 is probably more accurate.

It seems strange that the duc d'Antin and probably Boulle himself should have called this new type of chest a bureau, yet they may have seen it in connection with the bureau plat, a flat-topped desk with a large writing surface that was currently being developed. A very fine example of the celebrated Boulle bureau plat is the one made for Louis-Henri de Bourbon (1692–1740), prince de Condé, for the Château de Chantilly.

The design of the commode reflects the view of the late Louis Quatorze period that court art should be characterized by opulence and swagger. John Morley has pointed out that "the extraordinary way in which its body is, as it were, slung between the eccentric legs is somewhat reminiscent of carriage construction." Indeed, if the tapering spiral supports behind the paw feet could be removed, the resemblance would be even more striking. Like one of the splendid carriages that rolled down the road to Versailles––a moving "billboard" for the glorification of its owner––this commode was intended to impress.

Armchair

ca. 1685–89

British

The carved decoration includes lion and eagle heads, a lion and a unicorn, and the cipher JMRR within a wreath between them, indicating that the chair was made during the brief reign (1685–88) of James II and his queen, Mary of Modena, possibly as a gift to a high functionary of the court or an institution in the king's favor.

Sofa and Pair of armchairs (part of a set)

ca. 1835

Designed by Filippo Pelagio Palagi Italian

This sofa and two armchairs are from a set of furniture that also included a daybed, six side chairs, and two additional armchairs. The set was designed by the Bolognese architect Filippo Pelagio Palagi, who in 1832 was commissioned by Carlo Alberto, king of Sardinia, to redecorate his royal palaces. One of these palaces was at Racconigi, and Palagi designed this set of furniture for the principal drawing room next to the royal bedroom.

The armchairs and sofa are distinguished by the sculptural treatment of the crest rails and by the quality and refinement of the veneering. The set of furniture was executed by Gabrielle Cappello, whose workshop produced many of Pelagi's designs for Racconigi. The silk upholstery fabric on the armchairs and sofa is a reproduction of the original covering; it was woven by the textile firm that originally produced the fabric in the 1830s.

Medal cabinet

1760–61

Attributed to William Vile British

This medal cabinet, with 135 shallow drawers that can accommodate more than six thousand coins and medals, is one of two cabinets that probably formed the end sections of a larger piece of furniture, called His Majesty's Grand Medal Case. (Its mate is in the Victoria and Albert Museum, London.) The pair appears to have been commissioned by the future George III; the door of the top section is carved with the star of the Order of the Garter, to which the Prince of Wales had been elected in 1750. Originally the cabinets rested on open stands. William Vile made alterations to both cabinets, the most extensive of which was the filling in of the space between the legs.

Wig cabinet (cabinet de coiffure)

ca. 1685

Johann Daniel Sommer II German

This wig cabinet is one of the most elaborate examples of its kind, a work of great refinement and supreme craftsmanship. The exterior is decorated with extremely fine boulle marquetry, which retains many of the original engraved details. Furthermore, it is an early example of the migration of this type of metal-and-tortoiseshell (or horn) marquetry and the High Baroque style in French furniture to the German-speaking cultural areas (see the catalogue entries for acc. nos. 1986.38.1, 1986.365.3). It is obvious that the creator of this cabinet, Johann Daniel Sommer II, occupies a key position in the history of European furniture-making. Unfortunately, the most important facts about his career remain obscure. He was born in 1643 into a dynasty of craftsmen. His grandfather was a carpenter, and his father, Eberhardt Sommer (1610–1677), worked as a carpenter, master builder, and gunmaker in the Franconian town of Künzelsau beginning in 1642. Other members of the family are documented as skillful craftsmen and gifted sculptors. Johann Daniel married in Künzelsau in 1667 and lived there until 1679. Then he sold his properties and moved to an unknown destination. One of his elaborate pieces, a traveling apothecary made for Karl August, margrave of Brandenburg-Kulmbach (1663–1731), contains silver utensils stamped with the Augsburg town mark for 1692–1700. One of these objects, a mortar, is dated 1692. By the late 1600s, however, Augsburg silver, especially sets of toiletry and pharmaceutical items, was esteemed all over Germany; thus, the assumption that Sommer lived in Augsburg must remain speculative. Besides, in Augsburg Sommer could not have used painted horn as a substitute for tortoiseshell as is done in the Museum's piece. The town guaranteed the quality of its luxury goods and ruled that "nobody should be deceived with oxhorn."

Coffer

mid-17th century

Dutch

In contrast to the severe black exterior, the interior is more colorful and has several surprising components. The inside of the lid is embellished with an alabaster plaque painted with a monochrome landscape scene. The tiers of drawers and the central compartment are decorated with painted alabaster as well. Inside the central compartment is a mirrored five-sided recess with a tiled floor known as a perspectiefje (literally, "little perspective"), which held a small, treasured object that could be admired from all sides in the mirrors.

Cabinet

ca. 1700

Attributed to André Charles Boulle French

In 1688 the Parisian cabinetmaker Auburtin Gaudron, who worked for the French court after the death of Pierre Gole (ca. 1620–1684), delivered for Louis XIV's apartment at the Château de Marly a "large and beautiful cabinet with architectural bronze mounts and marquetry of copper and ebony with amaranth." Such armoires (closed cabinets or wardrobes) were ostentatious parade objects intended to stand grandly in a public room. The above description of the marquetry on Gaudron's armoire and of his piece's architectural form document that at this time André-Charles Boulle was not the only maker of these cabinets, for success has always sparked imitation in the competitive Parisian artistic environment. Nonetheless, the products of Boulle's workshop are distinguished from those of his competitors by sculptural details of unusual quality applied to the carcase structure. Boulle's furniture bears some of the best gilt-bronze ornaments ever made (see also 1982.60.82). The eight intricate corner mounts on the doors of the Museum's cabinet depict wind gods with flowing locks––six with a mature face and two with a young, beardless face-blowing a gale through pursed lips. The facade-like front, on a modest base with later toupie feet, is divided by a vertical molding of pilaster form with brass on tortoiseshell (première partie) marquetry. Its small capital penetrates an egg-and-dart molding with a projecting Vitruvian-scroll frieze above. The cabinet's top has concave sides and a rectangular base, lending the whole composition an almost pagoda-like look.

The patterns of the different inlaid panels correspond to those on other Boulle workshop pieces; these panels may have been prefabricated and held for stock, as mounts very often were, especially those frequently applied, such as rosettes, scrolls, and hinges. The mounts on the Museum's cabinet, which are integrated with and partly echo the two-dimensional inlaid decor, intensify the sparkling appearance of the piece. There are similarities between this cabinet and a remarkable drawing by Boulle in the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris that strengthen the attribution to Boulle.

Certain features of this cabinet shed light on the economically oriented nature of Boulle's workshop. The degree of chiseling and finish on the bronze mounts gradually increases as they approach eye level; moreover, the exotic and very expensive ebony––which was purchased by the pound––is replaced by ebonized local fruitwood in the upper quarter of the cabinet (above eye level). A similar thrift was practiced on the inside of the doors, which are not inlaid. Instead, they are veneered with local burl wood that was probably stained to imitate much more valuable tortoiseshell. Still, the interior must have looked strikingly attractive, especially when the three shelves (now lost) were filled with works of art or precious books. The outside of the Museum's armoire is for the most part veneered with contre partie (dark on light) marquetry, which was about 20 percent less expensive than première partie. This suggests that a matching cabinet decorated similarly but predominantly in première partie once existed. In spite of its enormous size, the object is surprisingly easy to dismantle; it comes apart in fifteen to twenty minutes.

The cabinet has unfortunately lost nearly all of its former engraved decoration, which means that its current appearance is distorted. This type of wear may be due to the materials used. Tortoiseshell and wooden veneer are organic, as is the oak used to build the carcase. The inlaid metal has a totally different coefficient of expansion, and as a result the boulle marquetry is constantly "working." Already in the eighteenth century it was said that major parts of the surface would have to be restored "every generation" (roughly every twenty-five to thirty years), and each smoothing of the surface reduced the depth of the engraved decoration and the thickness of the veneers themselves.

Cabinet

ca. 1645, with extensive later alterations

French, Paris

This imposing cabinet on stand belonged at one time to George Gordon Meade (1815–1872), the American Civil War general who led the Union troops to victory at the Battle of Gettysburg. Largely veneered with lustrous ebony, the architectural piece bears eloquent testimony to the importance to the European economy of overseas trade. In the seventeenth century, for the first time, tropical timber and other exotic materials became available in quantity to European cabinetmakers, who prospered as they set new fashions in furniture. Since imported wood was still a costly commodity in mid-seventeenthcentury France, the unknown cabinetmaker carefully layered the nearly black veneer on the cabinet’s superstructure to minimize the amount of ebony needed. Furthermore, he used blackened, so-called ebonized, pearwood for the lower part, which was, after all, not at eye level. The exterior is richly decorated with ripple moldings and engraved ornament and also displays carved biblical scenes from the Old Testament. Some of them, such as Judith with the head of Holofernes, are based on woodcut illustrations from Figures historiques du Vieux Testament by Jean Le Clerc, first published in 1596 and then in a second edition of 1614. In addition, female personifications of faith, hope, and charity, the theological virtues, are represented in the niches on the cabinet’s exterior, while two cardinal virtues, prudence and justice, are rendered on the interior doors. All the differently treated ebony surfaces reflect the light in various ways and give the object life. In marked contrast with the monochromatic decor of the outside, the central compartment, or caisson, on the inside is brightly colored with marbleized and tinted ivory, bone, and various kinds of wood. Treated as a sumptuous architectural interior, it was meant to surprise the viewer and enchant the eye. The use of mirror glass in the recess offers unexpected perspective views and allows a treasured object placed there to be seen and admired from different angles. Certain elements of this interior date to the late nineteenth century, when the cabinet underwent a major restoration by the leading New York cabinetmaking-and interior-decorating firm of Herter Brothers, whose name and the date 1884–85 are stamped twice on the back.

Jewel coffer on stand (petit coffre à bijoux)

ca. 1770

Coffer attributed to Martin Carlin French

Nine nearly identical coffers on stands are known (three in the Museum's collection) that are either stamped or attributed to Martin Carlin. Working in Paris, this successful German cabinet maker specialized in making light and elegant pieces for a fashionable and distinguished clientele. On December 13, 1770, the marchand mercier (dealer in luxury good) Simon-Philippe Poirier (ca. 1729-1785), who had a virtual monopoly on the purchase of Sèvres plaques, delivered "a coffer of French porcelain on a green ground with floral cartouches, very richly embellished with gilt bronze, and its stand" to Madame Du Barry (1743-1793), mistress of King Louis XV. Since seven of the plaques have the date letter R for 1770 painted on their backs, it has been suggested that this may have been the one commissioned by Madame Du Barry.

Boiserie from the Hôtel de Varengeville

ca. 1736–52, with later additions

French, Paris

Superb carving, partly in high relief, constitutes the chief glory of this room's boiserie, or wood paneling, originally from one of the private residences of eighteenth-century Paris, the Hôtel de Varengeville, which still stands, albeit much altered, at 217, boulevard Saint-Germain. Although the painted and gilded oak paneling is richly embellished with C-scrolls, S-scrolls, sprigs of flowers, and rocaille motifs, its decoration is still largely symmetrical and thus does not represent the full-blown Rococo style. The trophies allude to concepts and qualities such as music, gardening, military fame, and princely glory, and the long-necked birds perched on the scrolling frames of the mirrors and wall panels reflect contemporary interest in the exotic.

Download link (pdf, yandexdisk; 186 MB).

8 июня 2022, 14:11

1 комментарий

|

Партнёры

|

Комментарии

Добавить комментарий