|

|

Girard G., Lambot I. Life in Kowloon Walled City. — Hong Kong, 1993  City of Darkness : Life in Kowloon Walled City / by Greg Girard and Ian Lambot. — Hong Kong : Watermark Publications (UK) Limited, 1993. — 216 p., ill. — ISBN 1873200137

With contributions by

About this book

I cannot remember, now, when I first heard about the Kowloon Walled City.

It must have been in late 1979, shortly after I arrived in Hong Kong. It was still considered a dangerous place to visit at that time, and I clearly remember the strong feeling of being unwelcome.

I survived my brief forays then, and the few that followed over the years. It was always on my mind that I should photograph the City, but the opportunity never seemed to arise. And then, in 1987, the clearance was announced. It was now or never.

Other commitments intervened, but in the autumn of 1988 I started visiting the City regularly. At a Christmas party that year, a friend introduced me to Greg Girard who, it turned out, was doing just the same. A book was born.

To capture the flavour of the Walled City on the printed page has been an interesting challenge. Its density, its unexpectedness, its smells, its sounds and changing textures are difficult, if not impossible, to convey. The decision to use interviews was an early one. It always struck me that it was the people who lived and worked there who were the key to its extraordinary nature, as much as the place itself. The other contributions fell into place later as a way of rounding out the story.

In designing the book, I have tried to reproduce the 'spirit' of the City. Like the City, the book is crowded and has no real order. Certain themes have been brought together, but otherwise you can dive in anywhere and wander whichever way you choose. Every spread tells its own story, just as every door in the City opened to reveal its own slice of life. And there was no telling what would follow next. One could only explore, and each visit brought fresh rewards. I hope that the book is as enjoyable to 'explore' as it has been to put together.

Ian Lambot, Hong Kong, August 1993

This project and publication were made possible by the generous support of Po Chung and The Urban Council of Hong Kong. Contributions were also received from The Anglo-Hong Kong Trust and Hutchison Whampoa Limited.

A permanent archive of photographs and interviews from the project has been acquired by the Hong Kong Museum of History which has rights to use the material in its publications and activities. A similar archive has been placed with the Hong Kong Documentary Archive, Hoover Institute, Stanford University.

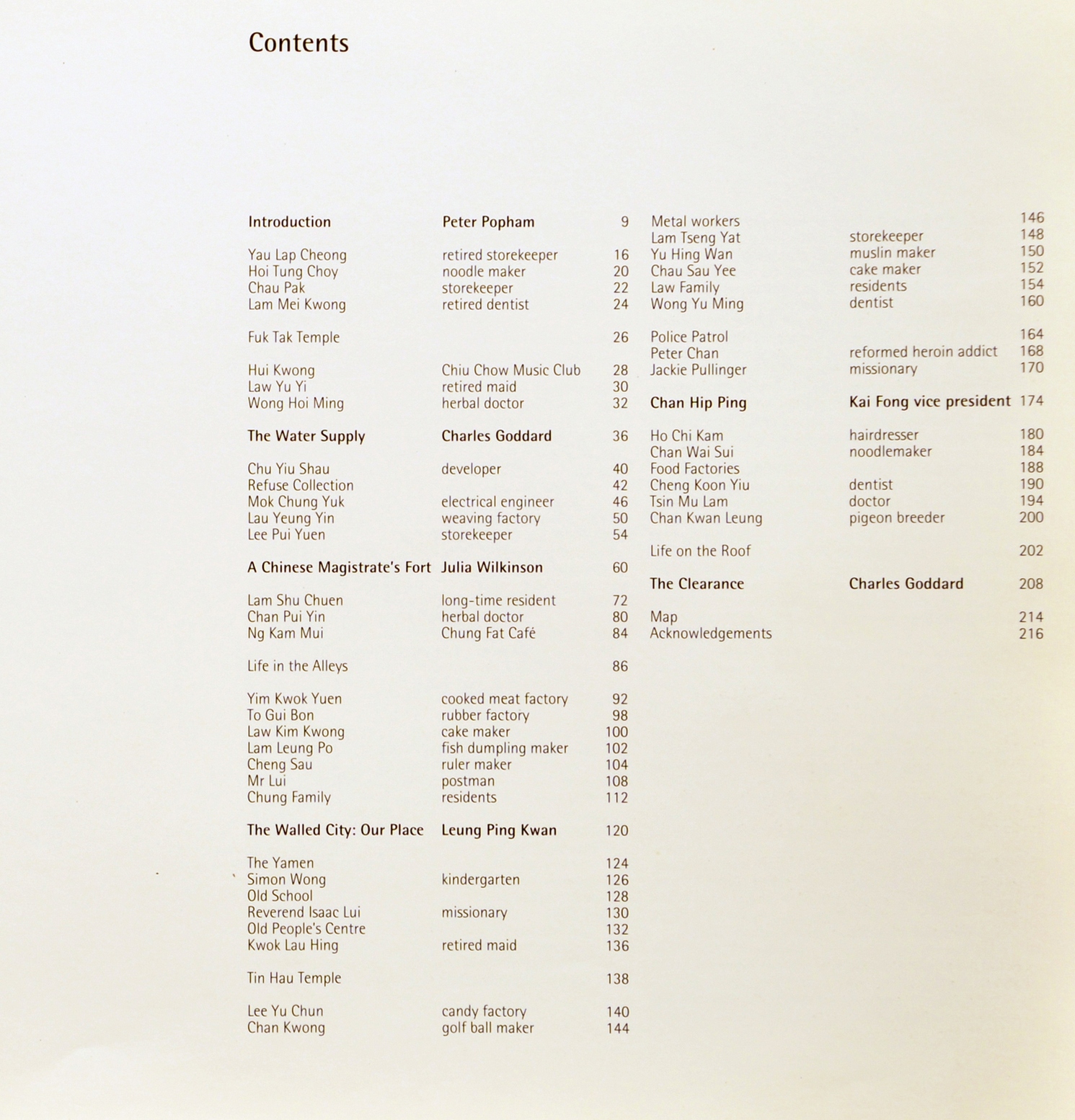

Contents

Introduction Peter Popham 9

Yau Lap Cheong retired storekeeper 16

Hoi Tung Choy noodle maker 20

Chau Pak storekeeper 22

Lam Mei Kwong retired dentist 24

Fuk Tak Temple 26

Hui Kwong Chiu Chow Music Club 28

Law Yu Yi retired maid 30

Wong Hoi Ming herbal doctor 32

The Water Supply Charles Goddard 36

Chu Yiu Shau developer 40

Refuse Collection 42

Mok Chung Yuk electrical engineer 46

Lau Yeung Yin weaving factory 50

Lee Pui Yuen storekeeper 54

A Chinese Magistrate's Fort Julia Wilkinson 60

Lam Shu Chuen long-time resident 72

Chan Pui Yin herbal doctor 80

Ng Kam Mui Chung Fat Cafe 84

Life in the Alleys 86

Yim Kwok Yuen cooked meat factory 92

To Gui Bon rubber factory 98

Law Kim Kwong cake maker 100

Lam Leung Po fish dumpling maker 102

Cheng Sau ruler maker 104

Mr Lui postman 108

Chung Family residents 112

The Walled City: Our Place Leung Ping Kwan 120

The Yamen 124

Simon Wong kindergarten 126

Old School 128

Reverend Isaac Lui missionary 130

Old People's Centre 132

Kwok Lau Hing retired maid 136

Tin Hau Temple 138

Lee Yu Chun candy factory 140

Chan Kwong golf ball maker 144

Metalworkers 146

Lam Tseng Yat storekeeper 148

Yu Hing Wan muslin maker 150

Chau Sau Yee cake maker 152

Law Family residents 154

Wong Yu Ming dentist 160

Police Patrol 164

Peter Chan reformed heroin addict 168

Jackie Pullinger missionary 170

Chan Hip Ping Kai Fong vice president 174

Ho Chi Kam hairdresser 180

Chan Wai Sui noodlemaker 184

Food Factories 188

Cheng Koon Yiu dentist 190

Tsin Mu Lam doctor 194

Chan Kwan Leung pigeon breeder 200

Life on the Roof 202

The Clearance Charles Goddard 208

Map 214

Acknowledgements 216

Introduction

by Peter Popham

Peter Popham grew up in London, and studied at the University of Leeds. Following graduation, he left for Japan in 1977 to practise Zen meditation in the Buddhist temples of Kamakura, later turning to journalism. As a Tokyo-based writer specialising in architecture, his feature articles have appeared in numerous newspapers and magazines around the world, including The Sunday Times and Geo. The author of several books, his exploration of the social genesis of Japan's urban architecture in Tokyo: The City at the End of the World (Kodansha, 1985) was published to considerable critical acclaim. He is currently a feature writer for The Independent Magazine, and lives in London. This article was first published in The Independent Magazine in May 1990.

Hak Nam, "the City of Darkness", the old Walled City of Kowloon has come down. Many people in Hong Kong, both Chinese and foreign, for whom it was never more than a disgusting rumour, believed it went years ago. Not so. Almost to the end it retained its seedy magnificence. It had never looked more impudent, more desperate, more evil to some eyes, more weirdly beautiful to others.

For many years its limits were blurred by a dense undergrowth of squatters' shacks that spread outward from it. As the first step towards clearing the whole site, these were swept away and replaced on two of the City's four sides by a dusty park where the landscaping is only now taking hold. The City reared up abruptly from the bare ground, 10, 12, in places as many as 14 storeys high, and there was no mistaking it: six-and-a-half acres of solid building, home to 33,000 people, the biggest slum in the world. It was also, arguably, the closest thing to a truly self-regulating, self-sufficient, self-determining modern city that has ever been built.

For a long time the Walled City was synonymous with all that was darkest and most threatening in China: opium dens, warring Triad gangs, huge rats and terrible drains. But during its final years, when proper policing meant that foreign intruders and inquisitive strangers no longer risked having their cameras smashed or their throats slit, it became possible to look at it in a different, more detached light.

What is a city in essence? How do we arrive at one that really works, that satisfies the deep emotional as well as the everyday needs of the people who live in it, to the same degree as the ideal sort of village? For all its squalor and its legacy of vice, Kowloon's Walled City offered some intriguing answers.

The City in its final, massive high-rise form went back barely 20 years. In origin, however, it was much the oldest part of Hong Kong, and one of the few areas in Kowloon populated in 1898 when the British acquired their 99-year lease on the New Territories. Hong Kong, the island, in the famously dismissive words of its first British governor, was no more than "a barren rock". By contrast, a settlement had existed on the site of the Walled City since 1668, and the 'city' itself was built in the mid-nineteenth century.

It was a proper Chinese town, laid out with painstaking attention to eternal principles: the Chinese believed that a town should face south and overlook water, with hills and mountains to the north. Given such conditions, the Yin elements (from the water) and the Yang (from the mountains) combine in such a way as to bless the lives of the inhabitants with harmony. The Walled City was in these terms very happily placed, with the great Lion Rock just to the north of it, and Kowloon Bay immediately to the south.

What the geomantic sages could not control were the infringements of the barbarians: first, marauding anti-dynastic rebels, and second, and far more devastating, the British. Under the terms of the 99-year lease, it was agreed that the Chinese would keep this, their ancient toehold on the peninsula, and would continue to exercise jurisdiction there until - or so the British believed - the colonial administration for the area had been established. This condition was never resolved, however, and the situation rapidly became irksome to the British. After military skirmishes between British and Chinese troops, they issued an Order in Council announcing that British jurisdiction was to be extended over the Walled City as well.

But the Order in Council remained unilateral, and a diplomatic stalemate ensued which was only ended in 1984 in the Thatcher-Deng agreement on the colony's future. Throughout the century of British rule, the Walled City has been an anomaly: within British domain, yet outside British control. Chinese officials left for good in 1899, but whenever the colonial authority tried to impose its will, the residents threatened to turn the attempt into a diplomatic incident. Until the Second World War the Walled City kept much of its old character, and offered a popular glimpse into the world of Old Cathay for foreign tourists.

The first body-blow to the place was delivered by the invading Japanese: they tore down the huge granite ashlar walls and used them to build Kai Tak Airport (the nucleus of which is still the colony's airport) on artificial land created in the shallows of Kowloon Bay. The former harmony was destroyed: the creation of the airport drove away the Yin spirit, which had been provided by the water. The City was abandoned. And with both walls and residents gone, effectively it ceased to exist.

What remained, however, was its status as a diplomatic black hole, and in the chaos of the War's aftermath it provided the perfect place of asylum for the great waves of refugees pouring south to escape famine, civil war and political persecution. Hong Kong remains to this day a territory peopled almost entirely by refugees and their descendants, which is the underlying reason for the universal uncertainty about reversion to China in 1997.

Even today illegal immigrants sneak across the border all the time, though many are booted straight out again. For many thousands of those who arrived in the 1940s and '50s, the City, surrounded now only by walls of political inhibition, was the place where they got their breath back: where they could live as Chinese among other Chinese, untaxed, uncounted, untormented by governments of any kind. Here the rents were mercifully low and no colonial busybodies snooped around asking questions about visas or licences, or working conditions or wages, or anything else.

Seemingly a single organic block, the 350 or so buildings of the Kowloon Walled City appeared as a rough parallelogram when seen from the air. Enclosing 2.7 hectares - or nearly 7 acres — the perimeter of the City followed the line of the old fort's former wall. As this could no longer be accurately pinpointed, the City had undoubtedly grown or receded in places. Taken in 1989, this aerial view shows the new park laid out on the site of the Sai Tau Tsuen squatter settlement which once mushroomed from the southern and western edges of the City.

The Walled City became that rarest of things, a working model of the anarchist society. Inevitably, it bred all the vices that the enemies of anarchism denounce. Crime flourished. The Triad gangs made the place their stronghold, and amassed fortunes operating their brothels and opium 'divans' and gambling dens. Undoubtedly, they kept many residents in a state of fear and subjection, which is the reason why, until very recently, outsiders trying to penetrate were given the coldest of shoulders.

But the City's economic activity was not restricted to vice. Many legitimate businesses flourished too, albeit in conditions of great squalor and exploitation. Refugees, who did not dare leave the place for fear of being picked up by the colonial police, lived there in a state of virtual slavery, penned up in cages when they were not sweating in the factories. The Walled City housed some of the colony's most prosperous textile factories, as well as plants turning out toys, sweets, metallic bits of this and that such as watch straps, and huge amounts of food. It was, for example, the principal source of that sine qua non of Hong Kong gourmandise, the fish ball.

Gruesome though these factories are up close, it is the presence of the legitimate businesses in the City which enables us to get a clearer perspective on the place. For a long time images of lurid evil dominated public perception of it. This satisfied the prurient, and often quite racist, curiosity with Chinese low-life, but obscured the Walled City's many positive achievements - some of which were really quite astounding, and might even lend new credibility to that old anarchist model.

Here you had a totally self-contained, land-locked, extra-legal community of tens of thousands of people crammed into a tiny space, each with one idea in mind: survival. Their needs were no different from anyone else's: water, light, food and space. Of these, water was the most indispensable. The only way to get it was to go down, and so that's what they did, just as they had back in the old ancestral village, sinking 77 wells in all around the City, to a depth of some 300 feet. Electric pumps shot water up to great tanks on the roof-tops, from where it descended via an ad hoc forest of narrow pipes to the homes of subscribers. Plumbing was created in the same pragmatic fashion, though not to a standard that would satisfy any rational authority. (What is amazing is that the sewers and the water supply did not get mixed up.)

To run the pumps and to light up the City's alleys required electricity, and this challenge was tackled in typically robust fashion: they stole it from the mains. Only in the 1970s, after a serious fire (much the most terrifying hazard in the City), were the electricity authorities allowed in with their meters.

Lo Yan Street, one of four major olleys that crossed the City from north to south.

Thus was the substructure of urban life banged roughly but workably into shape. And on top of this a crude - and, from our elevated standpoint, no doubt a dingy, seedy and undesirable - sort of society came to flourish. As already mentioned, there was industry of every description. There were also several schools and kindergartens, some of them run by organisations such as the Salvation Army.

Medical and dental care were no problem at all: many of the residents were doctors and dentists with Chinese qualifications and years of experience but lacking the expensive pieces of paper required to practise in the colony. They set up their neat little clinics in the City, oases of cleanliness and order, and charged their patients a fraction of what they would pay outside.

For the moments of relief from toil there were many restaurants on the City's fringes. Embedded deep in its heart, one of the few physical relics of the past was a temple, and there was a church as well. A born-again Christian English woman called Jackie Pullinger, who arrived in the 1960s, was quick to spot the potential harvest of souls to be had among the addicts and the downtrodden, and since then has been weaning addicts in the City off heroin with amazing passion and success. For the many residents who retained their poise and pride despite the living conditions, the City offered opportunities for relaxation too. Every afternoon the alleys were alive with the clacking of mahjong tiles. Up on the roof, in cages not much smaller than some of the City's homes, cooed hundreds of racing pigeons. A part-time Chinese orchestra got together twice a week, and the melancholic, sinuous notes of the old instruments filtered up and down the alleys.

For anyone who has wandered, enchanted and appalled, through the working-class back streets of Hong Kong or Macau, Greg Girard and Ian Lambot’s pictures will readily evoke the feel - and more particularly the smell - of the interior of the Walled City. But no images can do full justice to the experience of having been there.

There were no thoroughfares in the City - and no vehicles except the odd bicycle - only hundreds of alleys, each different. From the innocuous, neutral outside you plunged in. The space was often no more than four feet wide. Immediately, it dipped and twisted, the safe world outside vanished, and the Walled City swallowed you up.

It was dark and incredibly dank. It was impossible to stand upright because the roof of the alley was lined with a confusion of plastic pipes carrying water, many of them dripping. Immediately you were in, the symphony of stinks commenced: the damp, first of all, and underlying all the others; then, as you progressed, smells of incense - burned outside the homes - or charcoal, of putrefying pig's guts, of sweet-and-sour cooking, of raw and probably rotting fish, of burning plastic from a factory, of some sort of polish, of incense again, of mildew.

The light was dingy at best, deep green; there was the endless spatter of water leaking on to stone. One particularly ghastly little ginnel — spongily wet underfoot, a big rat hopping off - brought you to the gate of the Tin Hau temple, its courtyard had been shielded from the rubbish routinely heaved out of upstairs windows by wire netting which, as a result, was liberally spotted with bits of ancient filth, through which some real light occasionally filtered down, just like the light which dapples through leaves in a forest.

All this intensity of random human effort and activity, vice and sloth and industry, exempted from all the controls we take for granted, resulted in an environment as richly varied and as sensual as anything in the heart of the tropical rainforest. The only drawback is that it was obviously toxic.

We climbed and climbed the steps of an apartment block. Who would have been a postman in such a place? Yet there was a postal service, and because the alleys and blocks often had no names or numbers, the postmen had devised their own system, roughly daubing complicated numbers on each door to guide them.

We kept on climbing and slowly it got a little better. The smells were diluted. Something like oxygen made its presence felt. The light brightened. We emerged finally at roof level, the only part of the Walled City where there was any space to spare. From there the awesome size of the place, which was essentially a single lump of building, became apparent.

A typical section of external facade, horizontally uneven ond animated with balcony life.

The blocks were built at different times, of different heights and materials. Some were quite sophisticated: one of the largest, for example, was a copy of an early Hong Kong municipal housing block, designed by housing authority architects in their spare time. Some had home-made annexes of brick or iron or plastic fastened on to the roofs, but all were jammed up flush against each other so that an agile cat could circle the place at roof level without difficulty. The roof had various functions. One of the municipal services which the Walled City never really got to grips with was rubbish collection. Somehow or other they disposed of the organic, but the inorganic - old television sets, broken furniture, worn-out clothes, bedsprings and the like - they lugged up to the roof and abandoned. In among these unaesthetic piles of junk, village life continued.

Washing was strung up between the thousand television aerials. Small children played something like hopscotch under the eyes of old ladies. Pigeons cooed sonorously. And every 10 minutes or so another jumbo jet descended on Kai Tak Airport - heading straight for the Walled City and, skimming so low, it was surprising that it did not make its final descent festooned in laundry.

What fascinates about the Walled City is that, for all its horrible shortcomings, its builders and residents succeeded in creating what modern architects, with all their resources of money and expertise, have failed to: the city as 'organic megastructure', not set rigidly for a lifetime but continually responsive to the changing requirements of its users, fulfilling every need from water supply to religion, yet providing also the warmth and intimacy of a single huge household.

As the sun finally sets on this vast slum, there is perhaps cause enough to don rose-coloured spectacles and praise it.

In this photograph of 1990, the south side of the Walled City is seen facing on to the new public park, its formal greenery yet to take hold.

Скачать книгу в формате pdf (яндексдиск; 506 МБ). Издание выкладывается в научных и образовательных целях.

17 ноября 2014, 3:13

0 комментариев

|

Партнёры

|