|

|

H. Avray Tipping. English Homes of the Early Renaissance : Elizabethan and Jacobean Houses and Gardens. — London, 1900  English Homes of the Early Renaissance : Elizabethan and Jacobean Houses and Gardens / Edited by H. Avray Tipping, M.A., F.S.A. — London : Published at the offices of Country Life, 1900. — LXIV, 423, 16 : ill. — (In English Homes).CONTENTS.

INTRODUCTION ... xiii.

BATEMANS

Near the Sussex village of Burwash, which was a centre of the old iron trade, was no doubt built by a local ironmaster, the date on the porch being 1634. It is now the property of Mr. Rudyard Kipling ... 285

BORWICK HALL

Was a “berewick” or subordinate manor of the extensive Lancashire parish of Warton. An older Peel-towered home was remodelled by Robert Bindloss, a Kendal clothier, in 1595. It is now the residence of Mr. J. A. Fuller-Maitland ... 163

BOYTON HOUSE

In the Wiltshire Valley of the Wylye, was completed by Thomas Lambert in 1618. It has descended through heiresses to its present owner, Mr. M. H. N. Fane, but owes much of its charm to the late tenant, Mr. H. Moffat ... 299

BRECCLES HALL

Near the Norfolk town of Attleborough, dates largely from about the middle of the sixteenth century, but was added to in 1583 by Francis Woodhouse. It was recently carefully renovated and enlarged by the Hon. Charles Bateman-Hanbury, under the advice of Mr. Detmar Blow, and is now the property of Mr. J. G. Hossack ... 35

BRERETON HALL

Near Sandbach in Cheshire, was built by Sir William Brereton in 1586. Although it suffered much from alterations in the early part of the nineteenth century, it retains many fine original features. It is the residence of Mr. A. Moir ... 199

BROUGHTON HALL

On the borders of Staffordshire and Shropshire, is a timber-framed house completed by Thomas Broughton as late as 1637, but very Elizabethan in character. The timber-work has mostly been buried under rough-cast. It is the property of Sir Delves L. Broughton, Bart. ... 321

BURFORD PRIORY

In Oxfordshire, was built by Sir Lawrence Tanfield in the latter part of Elizabeth’s reign. Speaker Lenthall afterwards owned and altered it. It became ruinous at the close of the nineteenth century, but has recently been well renovated, and is owned by Mr. Horniman ... 217

CASTLE BROMWICH HALL

Lying five miles out of Birmingham, was built by Sir Edward Devereux about 1600. It became the property of Sir John Bridgeman in 1657, to whose descendant, the Earl of Bradford, it belongs ... 337

CAVERSWALL CASTLE

In North Staffordshire, was built on the site of a mediæval castle by Mathew Cradock in James I.’s time. The moat is now drained and gardened. It is the residence of Mr. W. A. Bowers ... 329

CHARLTON HOUSE

Near Greenwich in Kent, was built by Sir Adam Newton in 1612. It has retained most of its original features and is a seat of Sir Spencer Maryon-Wilson, Bart ... 393

THE CHARTERHOUSE

In London, was transformed from a monastic house to a lay residence by Sir Edward North, who acquired it in 1545. The Duke of Norfolk altered it before 1571, and in 1611 it was acquired by Thomas Sutton, who turned it into a hospital for old men and boys ... 81

CHAVENAGE

In the Cotswold district of Gloucestershire, was built or remodelled by Edward Stephens in 1576. It has recently been enlarged by its present owner, Mr. G. Lowsley-Williams ... 1

CHEQUERS COURT

In Buckinghamshire, lies amid the Chilterns, and was largely built by William Hawtrey about 1563. The interior was treated in mock-Gothic manner a century ago, but has recently been put back into much of its original condition by the present tenant, Mr. Arthur Lee, M.P., under the advice of Mr. Reginald Blomfield ... 99

COBHAM HALL

In North-East Kent, was built in 1584 by Lord Cobham, but partly rebuilt under Charles I. by the Duke of Lennox. It is the seat of the Earl of Damley ... 157

COTHELSTONE MANOR

Situate on the slopes of the Quantocks in Somerset, was built by Sir John Stawel about 1600. It suffered in the Civil Wars and was deserted by the Stawels at the Restoration. The remaining portion was carefully repaired in 1867 by the grandfather of the present owner, Mr. C. E. J. Esdaile ... 305

DANEWAY HOUSE

Near Cirencester, is a small Cotswold house typical of the good local work that prevailed in the sixteenth century. It is now owned by Earl Bathurst ... 251

DERWENT HALL

In the High Peak district of Derbyshire, is a Jacobean house remodelled by Henry Balguy in 1676. It is now the property of the Duke of Norfolk ... 271

DODDINGTON HALL

Near Lincoln, was built by Thomas Tailor in 1600. Sir Thomas Hussey, under William III., and Lord Delaval, under George III., altered the interior. It was bequeathed to Colonel Jarvis in 1829, and is now owned by his grandson, Mr. G. E. Jarvis ... 387

EAST QUANTOCKSHEAD COURT HOUSE

In West Somerset, is a very ancient seat of the Luttrells, but the house was remodelled by George Luttrell in James I.’s reign. Long used as a farm, it is now again a residence of the family ... 313

GWYDIR CASTLE

Near Llanrwst in North Wales, was acquired by the Wynns ere the fifteenth century closed. The present house was mostly built by John Wynn in 1555. There is also much Jacobean work. It is now owned by the Marquess of Lincolnshire, who had a Wynn ancestress ... 111

HALL I’ TH’ WOOD

Close to Bolton in Lancashire, is a house of which the timber-framed portion dates from Elizabeth’s reign, and the stone-built part from that of Charles I. It is now owned by the Corporation of Bolton and used as a museum ... 191

KILDWICK HALL

Is a little Yorkshire manor house near Keighley which was built by the Currers in the early part of the seventeenth century. Its ownership has continued by inheritance, but it was long the residence of the late Sir John Brigg, M.P. ... 277

KIRBY HALL

Near Kettering in Northamptonshire, was built from Thorpe’s plans by Sir H. Stafford about 1570, but altered and completed by Inigo Jones for Lord Hatton in 1640. It fell into ruin from neglect towards the end of the nineteenth century, but what remains is now well cared for by the present owner, the Earl of Winchilsea ... 69

LAKE HOUSE

Near Stonehenge in Wiltshire, was built by George Duke soon after he acquired the estate in 1578. It became the property of Mr. J. W. Lovibond in 1897, who repaired it under the direction of Mr. Detmar Blow. It was gutted by fire in the spring of this year (1912), but is being rebuilt ... 293

MADINGLEY HALL

Four miles from Cambridge, was built by Sir John Hynde in the middle, and altered by his descendants at the close, of the sixteenth century. It was occupied by the late King Edward VII. in his undergraduate days, and is now the property of Colonel T. W. Harding, who has carried out extensive renovations under the advice of Mr. Alfred Gotch ... 57

NETTLECOMBE COURT

Nestles under Exmoor in Somerset. It passed from Raleighs to Trevelyans in the fifteenth century, of whom John Trevelyan built the present house in the latter days of Queen Elizabeth. His descendant, Sir Walter Trevelyan, Bart., is the present owner ... 139

OWLPEN MANOR

Near Dursley in Gloucestershire, belonged for many generations to the Daunts, one of whom will have built the house under Elizabeth. It has descended to Mrs. Trent-Stoughton ... 257

PARNHAM HOUSE

Near Bedminster in Dorset, was built by Robert Strode before the end of Henry VIII.’s reign. Nash did much damage in 1810. Recently it was renovated by the late Mr. Vincent Robinson, after whose death it was acquired by Mr. Hans Sauer ... 9

PLAS MAWR

In the Carnarvonshire town of Conway, was built in Elizabeth’s reign by Robert Wynn, whose descendant, Lord Mostyn, owns it, but it is rented by the Royal Cambrian Academy of Art ... 121

QUENBY HALL

Near Leicester, was built in James I.’s reign by George Ashby. It continued in his line until recently, but is now the property of Lady Henry Grosvenor, who has renovated it with judgment ... 371

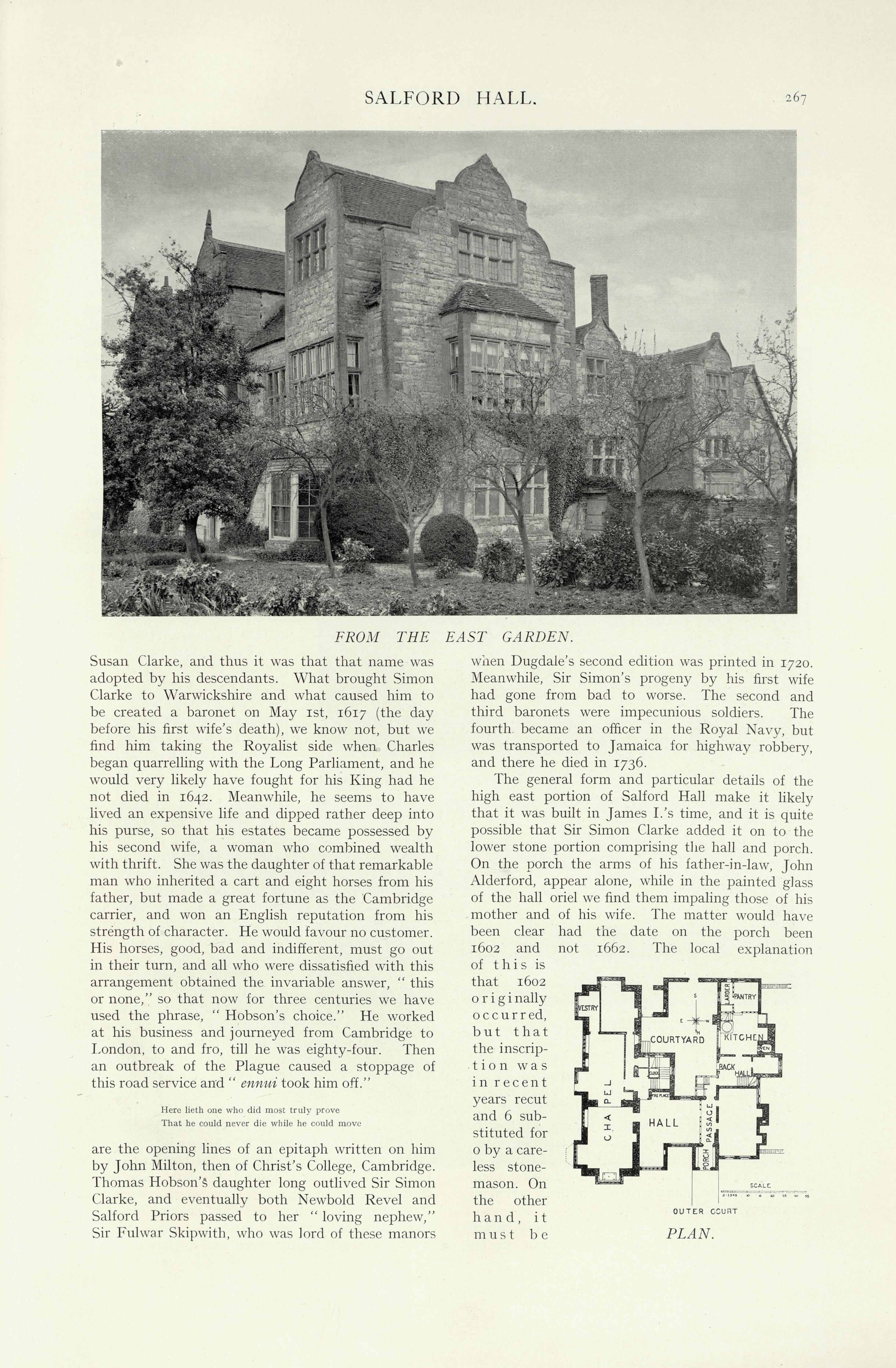

SALFORD HALL

On the Warwickshire Avon, was built about 1600, probably by John Alderford. It is now the property of Mr. C. Turberville Eyston ... 263

SECKFORD HALL

Near Ipswich in Suffolk, was built by Thomas Seckford in late Elizabethan times. Part is in ruins and part used as a farm. It is the property of Mr. E. G. Pretyman, M.P. ... 51

SHAW HOUSE

Near Newbury in Berkshire, was largely built by Thomas Dolman, who completed his work in 1581. Alterations were made about 1700, and the present owner, Mrs. Farquhar, has renovated it under the advice of Mr. Fielding ... 207

SHERBORNE CASTLE

In Dorset, is a house, long known as the Lodge, which Sir Walter Ralegh built near the older castle in Elizabeth’s time. It was enlarged and altered by the Digbys under the Stewarts. It is now the seat of Mr. F. Wingfield Digby ... 147

SHIPTON HALL

Near Wenlock in Shropshire, dates from about 1600. Alterations, especially in the interior, were made in the early part of the eighteenth century. Long a seat of the Myttons, it now belongs to Mr. C. Bishop ... 243

STONYHURST COLLEGE

On the edge of the moorlands that divide Lancashire and Yorkshire, was the Elizabethan home of Sir Richard Shirburn, altered by his descendant, Sir Nicholas Shirburn, under William III. It became a Roman Catholic College in 1794, and is now owned by the Society of Jesus ... 171

STUDLEY PRIORY

On the high ground above Otmoor in Oxfordshire, was a Benedictine nunnery which, at the Dissolution, was bought by John Croke. He and his immediate descendants transformed it into a lay habitation, and it remained in the family till the middle of the nineteenth century. It is now the property of Mrs. Henderson ... 25

TISSINGTON HALL

Near Ashbourne in Derbyshire, came to the Fitzherberts in the fifteenth century. It is rich in panelling and other interior fittings of the Jacobean period. It has recently been renovated and enlarged from plans by Mr. Arnold Mitchell, and is the seat of Sir Hugo Fitzherbert, Bart ... 357

TRERICE MANOR HOUSE

Near Newquay in Cornwall, was built by John Arundell in 1573. A portion only remains, and is owned by Sir C. T. Dyke-Acland, Bart ... 129

WATER EATON MANOR

Near Oxford, was built by one of the Lovelaces in 1585. It was carefully renovated by the late Mr. Bodley, R.A., who occupied it until his death, and it is now the residence of Mrs. Bodley ... 229

WISTON PARK

Near Steyning in Sussex, was for long the home of a branch of the Shirleys, and was built by Sir Thomas Sherley in the early part of Elizabeth’s reign. It is now the seat of Mr. Charles Goring ... 89

WOOTTON LODGE

In the Staffordsnire parish of Ellastone, was built by Sir Richard Fleetwood in James I.’s reign. Injured during the Civil Wars, it was renovated after the Restoration, and is now the residence of Colonel B. C. P. Heywood ... 347

YARNTON MANOR

Near Oxford, was built by Sir William Spencer about 1612. It fell into decay and was used as a farmhouse, but was renovated a few years ago by Mr H. R. Franklin. It is now owned by Mrs. Franklin ... 237

INTRODUCTION

THE object of this volume is to bring clearly before its readers, by means of description and illustration, the nature and characteristics of country homes built by Englishmen during the hundred years that elapsed between the close of Henry VIII.'s reign and the outbreak of Civil War in 1642.

It was a time when many men—those of moderate means quite as much as the very wealthy— were rehousing themselves, and a very considerable amount of their work survives to our day. It is not, of course, wholly untouched. We have no house of which either fabric or furnishing is just as it was when its builder held his house-warming under Elizabeth or James. To greater or less extent succeeding generations of owners have left their mark, and often much of the charm of our country places depends on such changes, which afford not only a pleasant variety, but also add a human interest and a sense of historic continuity altogether agreeable and sympathetic. As regards the forty-three places that form the body of this work, however, it may be said of nearly all of them that they have so largely retained their original character as to be, in their entirety, almost as typical of the style which we call Early Renaissance as are the selected details that illustrate this Introduction.

The style is not very felicitously named, since it uses a French word to describe a product very largely English and of which the foreign elements came from Italy and Flanders rather than from France. But no satisfactory substitute has been found. It were apt indeed if styles could be called after dynasties. But they will not run in pair-harness, and their changes refuse to be accommodatingly synchronous. The somewhat persistent habit of speaking of a “Tudor” style merely leads to confusion. The century of the Tudors saw as many revolutions of mind as the previous century had suffered revolutions of government. When it opened, a quite mediæval and native style of architecture prevailed, and for some decades continued to prevail. When it closed, the new spirit that had come across the Continent from Italy had fully leavened all branches of English thought and endeavour. Moreover, it had done its work with sufficient completeness to produce a lull, and so, for a while, there was little onward movement. And thus, just as the new style of architecture came, not with the advent of the Tudors, but forty years later, so did it continue for forty years after the passing away of the last of that line. Hence we must abandon not only the dynastic name, but also one combining that of the last Tudor and the first Stewart. This is perhaps no misfortune, for Elizabetho-Jacobean would have been a rather terrible word to adopt. As a matter of fact, the new architectural style was so sturdy an infant before Henry VIII. died that it were a preposterous concealment of birth to date it so late as the accession of Elizabeth. And though its period of amplest growth and fullest development did coincide with her reign and that of James I., yet it did not end with him. English conservatism was strong enough to resist any rapid and general spread of the full classic manner that Inigo Jones adopted in 1619 for the Whitehall Banqueting House. Thus English Renaissance architecture cannot be said to have definitely passed from its Early to its Late phase until the monarchic Restoration of 1660.

In the absence of a better name, therefore, that of Early Renaissance must be retained for the period under review, and that period may be taken to extend from rather before the middle of the sixteenth century to rather beyond the middle of the seventeenth. But it must be borne in mind that no style begins or ends suddenly. When Henry VIII. came to the throne in 1509 he employed Pietro Torrigiano to make his father's tomb, and that tomb remains to this day as the earliest example of Italian Renaissance work made in England. The King, and some of the leading men of his Court and Camp, headed by Wolsey, were keenly alive to those foreign influences with which their own Continental journeyings and campaigning brought them in contact. They were, however, the select few among whom may not be included a single one of those with whom the first and last word in architecture then really lay—the master-masons and the various craftsmen associated with them. In the days of powerful guilds and strict apprenticeship, inherited instincts and transmitted aptitudes held dominant sway. Stirred by the rising intellectual movement, a young man might, here and there, seek to reap of the fertile crop of reborn classic architecture which was beginning to overflow from Italy. But teachers and examples were wanting, and the little he could learn from the few foreign artificers that had been attracted to England by Royal patronage in no way sufficed to free either mind or hand from the bondage of custom and environment. By the Italians and their English copyists a sprinkling of new ornament was set upon old forms, but the late phase of Gothic continued during the first half of the sixteenth century in such strength that the Renaissance spirit, in its attack, for long only effected a very occasional and superficial lodgment, and, at length, when Elizabeth was Queen, made terms and signed a partition treaty.

The Early Renaissance style, in England, is a welding of new and old, a classic veneer upon a Gothic framework, and it is not until the Later Renaissance period, that is, after 1660, that the heritage of mediævalism was entirely discarded.

That is true of the disposition as well as of the design of houses—of their ground plan as much as of their elevations and decorations. In this volume we shall come across the direct descendant of the Gothic hall and its adjuncts as frequently as we shall see the finialled gable, the mullioned window, the arched fireplace and the ribbed plaster ceiling, all of which have much more indubitable mediæval pedigrees than some of the great Elizabethans for whom they were wrought. When we consider that, as a classic innovator, seventeenth century Inigo Jones was somewhat before his time, we cannot wonder that sixteenth century John Shute had so little influence upon his generation that he left scarce a record of his architectural effort beyond a meagre treatise with an ample title. Mr. Lawrence Weaver, who has recently given us an admirable fac-simile edition of “The First and Chief Grounds of Architecture,” sought earnestly for new material to make a satisfactory biography of Shute. But he found little flesh to clothe the skeleton that has come down to us. John Shute and his book are chiefly of importance to us as showing that, as early as the reign of Edward VI., there was an Englishman, styling himself “Archytecte,” who visited Italy to study classic architecture at its source, and who prepared an illustrated work with a view of bringing the principles of the art, as laid down by Vitruvius and interpreted by Serlio, definitely and exactly before English builders. That they took little heed of the opportunity may have been partly due to the sudden fall of Shute’s patron, the Duke of Northumberland, in 1553. Some time before that date Shute had returned from Italy, whither the Duke had sent him, with portfolios of “tricks and devices,” and these had been submitted to Edward VI. The political crisis which cost the Duke his head seems also to have relegated the portfolios to an upper shelf. A decade passed before “The First and Chief Grounds” found a publisher, and the year 1563 on its title-page is also the year of its author’s death. A few designers, such as the builder of Longleat, must have known the book, if not also the Italian sources that inspired it. But popular as the classic orders (with which it almost exclusively deals) were from the first days of Elizabeth, yet they were habitually used as mere ornaments to a building alien to them in origin and principle, and without knowledge of the strict mathematical and geometrical rules that should govern their form and arrangement.

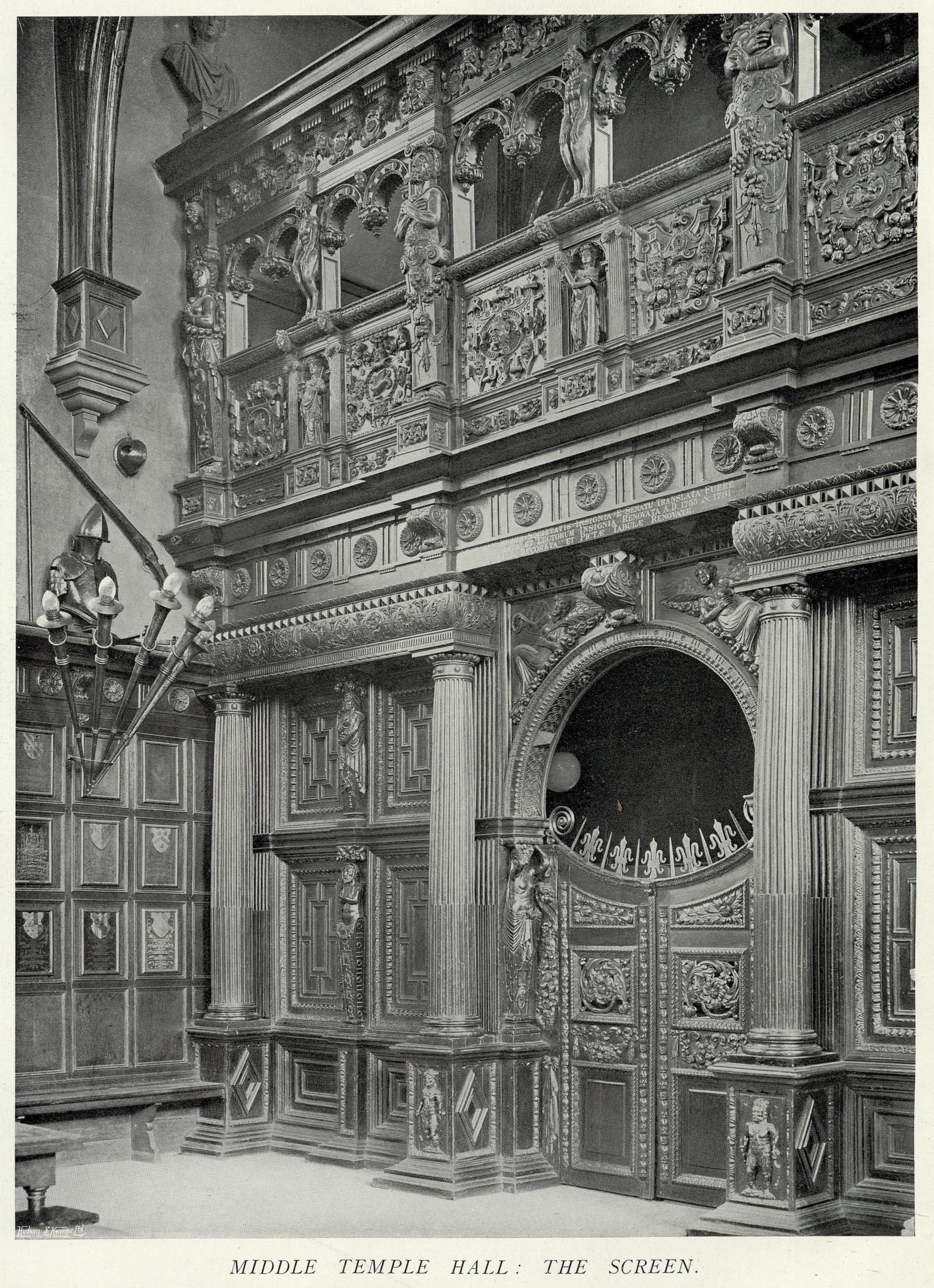

MIDDLE TEMPLE HALL.

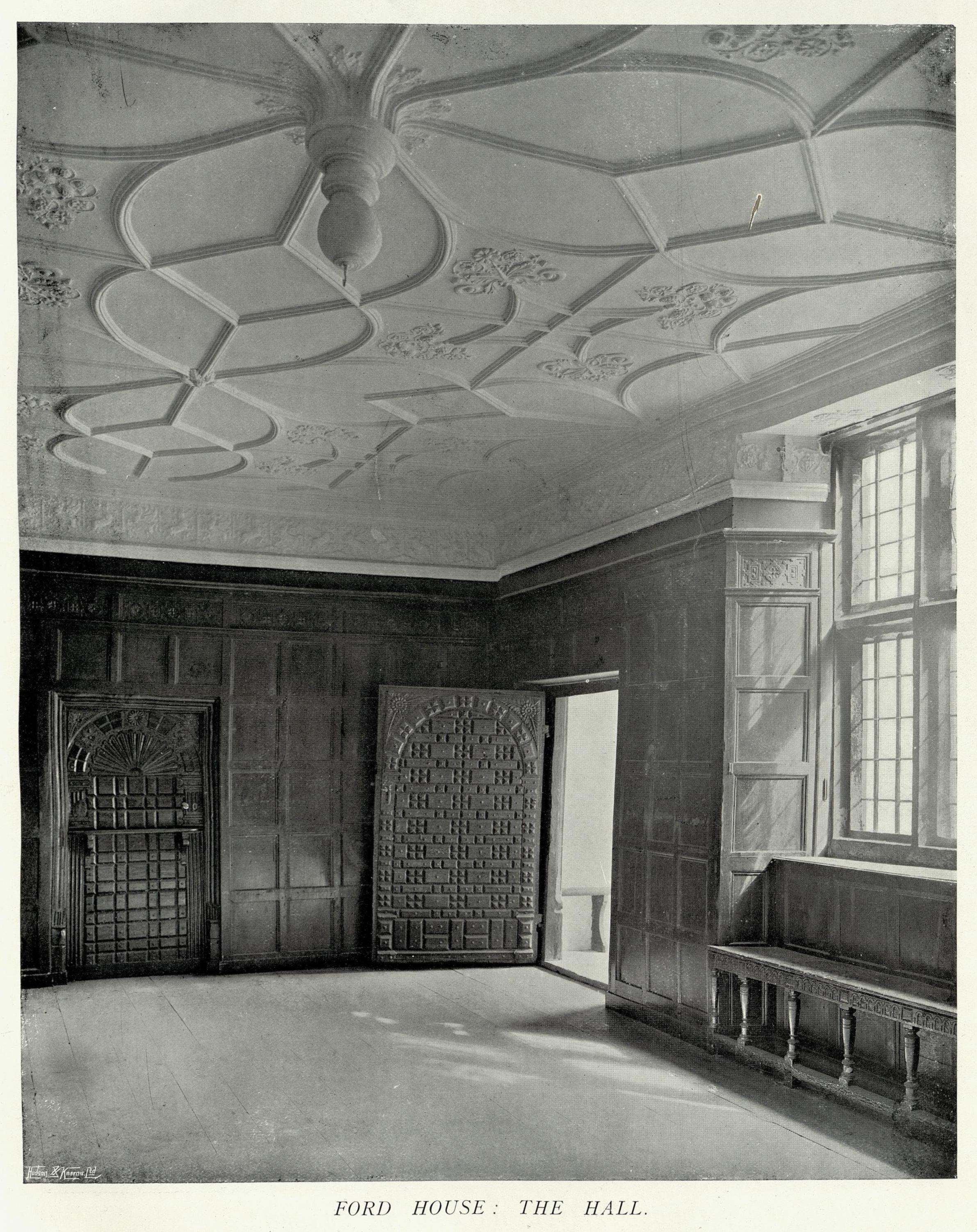

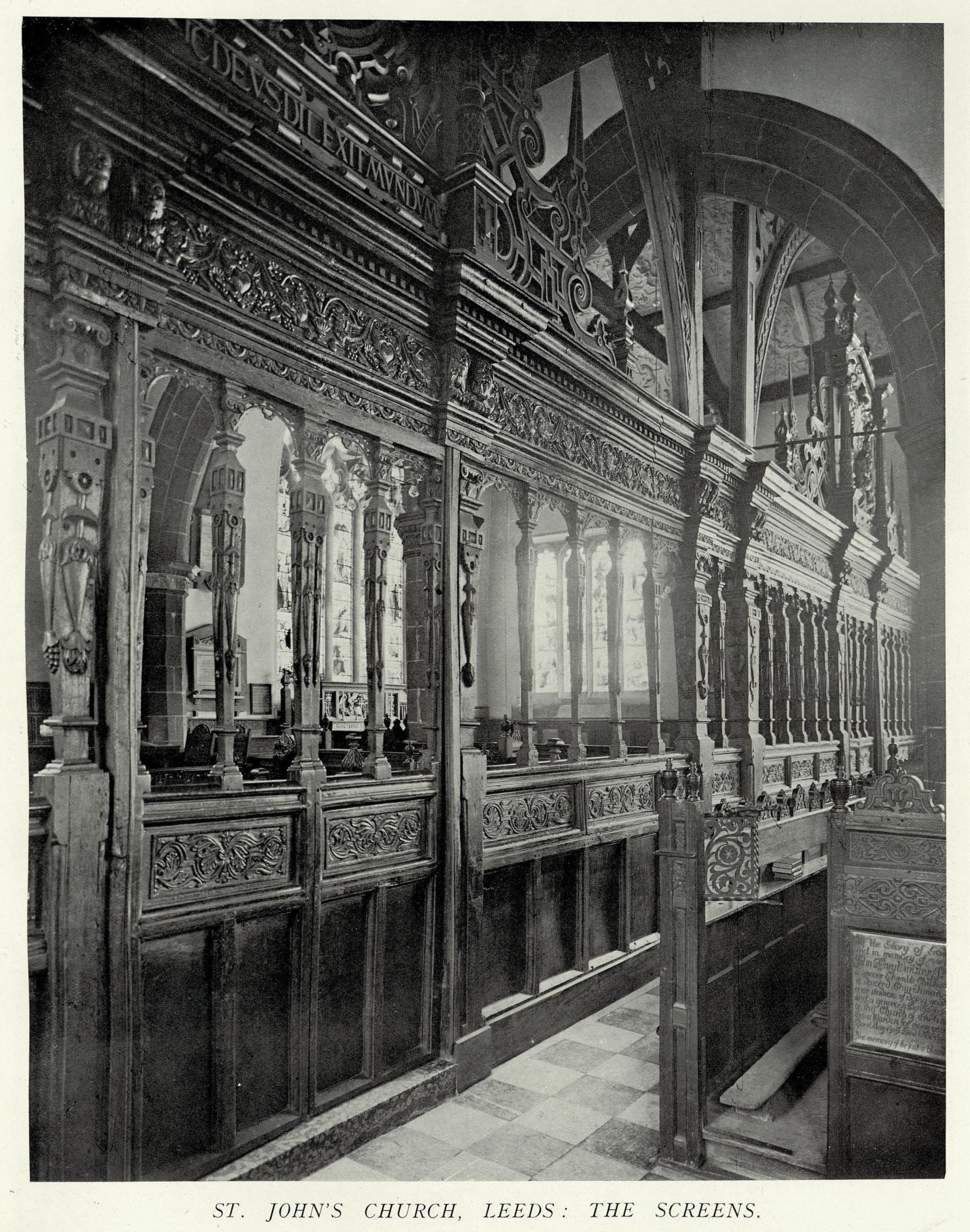

To reach an appreciative understanding of an Elizabethan country home, it is, therefore, well for us to glance less at sixteenth century Italy than at fifteenth century England. Despite the check given to the arts of peace by the Wars of the Roses, the question of ample and more commodious housing was receiving much attention for some while before the Tudors gave peace to the land. There is considerable commodiousness as well as architectural charm in what remains to us of the domestic buildings of that age, wherein there appears a strong tendency to diminish the importance of the hall. It may almost be said that, except in the castles of the great, the mediæval Englishman’s hall was his house. It was the chief and central building, attached to the two ends of which were subsidiary buildings. Their length ran at right angles to the length of the hall, and so the gable ends of the latter rose up above and independently of the roofs of the former. Thus, even from the exterior, the hall proclaimed itself. It was the one large apartment and was for general use by all the inmates—high or low—when the calls of work or the desire for seclusion did not cause them to occupy their respective quarters in the end buildings. Across the lower end of the hall stretched the screen, and over it was a gallery used occasionally by minstrels. The doors from the body of the hall through the screen gave into a passage, at one end of which was the porch or principal entrance, and at the other end a subsidiary door leading to outbuildings, probably arranged round a base court. Facing the screen doors were others piercing one of the main end walls of the hall. The full arrangement here was to have three doors, of which two opened respectively into buttery and pantry, while through the centre one a passage was entered leading to the kitchen. This disposition may still be traced on the plan of The Charterhouse on page 84. The opposite or upper end of the hall was habitually raised a step. On the dais thus formed stood the high table for the owner, his family and guests. A great oriel window here offered a pleasant and light recess, while one or more doorways led to a solar or parlour and to one or more principal chambers. Over the buttery and its associated offices were other chambers, and a staircase in each of the end buildings was a necessity, for the hall occupied the whole width of the central building, was lit from both sides and went up to the roof, so that there was no possible upstair access from one wing to the other. Such was the altogether dominant position of the mediæval hall, which the later fifteenth century builders sought to lessen relatively by increasing the accommodation at either end. Offices were enlarged, chambers multiplied. Parlours were greater in number and size, and were differentiated in their use, the owner and his family habitually dining apart in one of them. Yet even a century later this description of the mediæval hall and its adjuncts will very nearly answer for that at Kirby (page 69), a house designed to incorporate the most advanced views of its time. Designers may have been anxious to show their knowledge of foreign “tricks and devices,” but they were merely treated as details. Houses in plan and elevation were made by Englishmen for Englishmen whose habits and ideas in the matter of their domicile and mode of home living proved more conservative than in the matter of religion and politics, education and commerce. The fifteenth century began the work of deposing the hall from its pre-eminence, yet it took the whole of the sixteenth to complete the task.

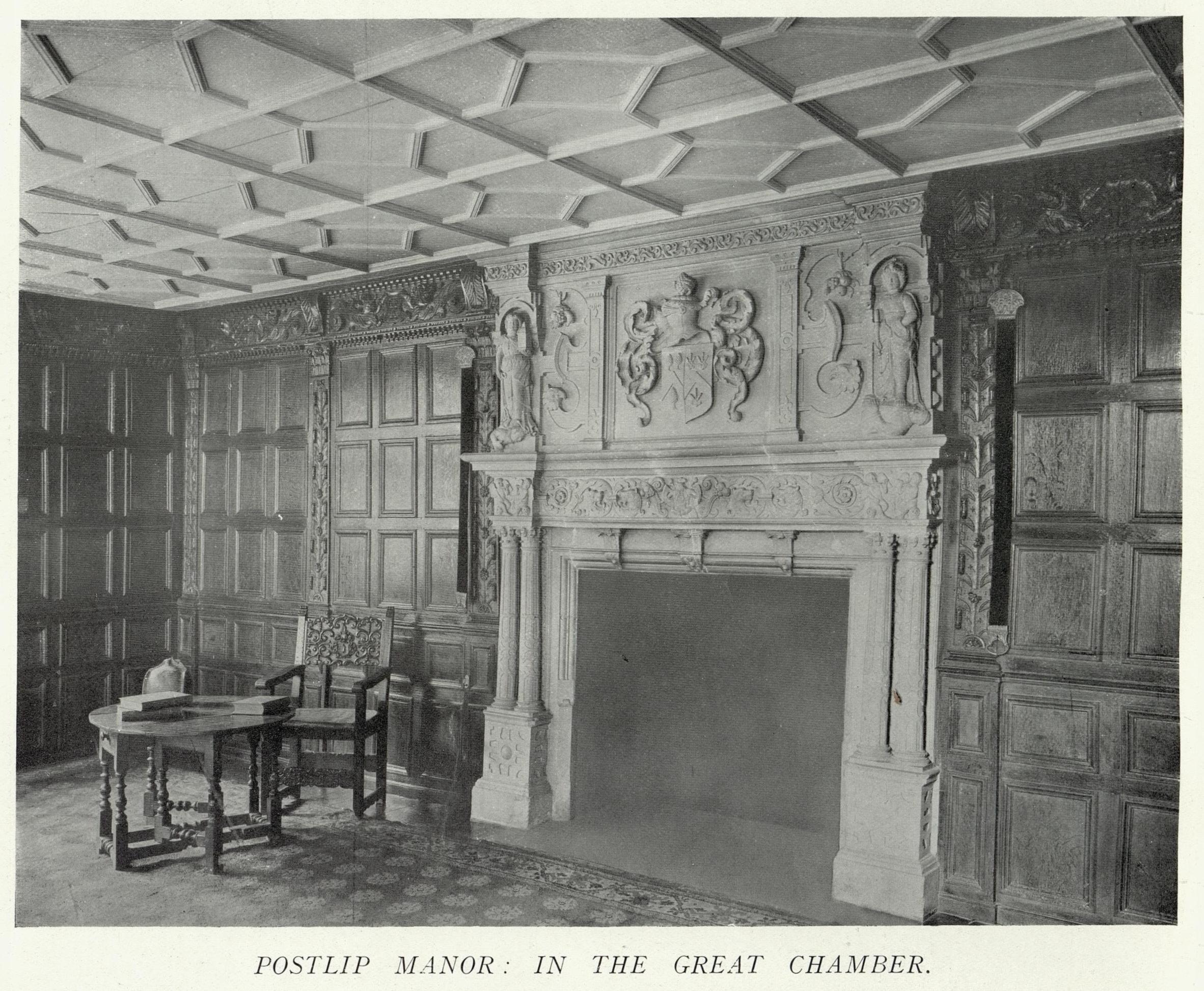

Nowhere can the effort to accomplish this be better studied than in the book of drawings of plans and elevations preserved at the Soane Museum and attributed to John Thorpe. Almost less of him is known than of John Shute ; in fact, it is not absolutely established whether he is one or two persons—a father and a son of the same name—but the latter is the accepted view. Authorities agree that many, if not all, of the drawings in the book, whether of ground plans or of “uprights,” are by the hand of the elder Thorpe. On the plan of Kirby (page 74) will be seen, in his own handwriting, the statement that he had himself laid the first stone in 1570. In the case of what is now known as Holland House, the drawing shows different coloured inks, as if suggesting alterations and enlargements, and on it is written: “Sir Walter Coap at Kensington perfected by me J. T.” It is, then, certain that Thorpe was closely connected with the designing and building of Kirby and of Holland House. We shall find it most probable that he also had much to do with Charlton (page 396). A certain number of the drawings that make up the collection represent plans of houses that never were built or that have long ago disappeared. Some, again, are mere exercises in ingenuity, while a few are speculative adaptations from Flemish books of design. But taken together they show an effort at setting aside mediæval dispositions and forms, and at adopting an arrangement and a style consistent with the new taste inspired from Italian sources and with habits of life which surely, though slowly, were undergoing modification. The same lesson is taught by surviving houses of the period, such as those selected for this volume. In the department of planning, the chief tendency was to reduce the importance of the hall, not merely relatively but actually. In houses of considerable extent, a hall great in size and rising to the roof is occasionally retained under Elizabeth, as by Thorpe himself at Kirby (page 79). Among other examples included in this volume is the hall at The Charterhouse (page 87), where the roof dates from about 1568, but merely replaced one of Gothic period—the hall being adapted from the monastic guest house by its lay owners. The roof modestly resembles that of about the same date in the hall of the Middle Temple (page xv.), a building begun in 1562, and first used ten years later. The roof assimilates in construction to those erected by Edward IV. at Eltham Palace and by Wolsey at Hampton Court. Even the latter is still essentially Gothic in both form and detail, although its corbels, pendants and spandrels exhibit Italian details such as Torrigiano had then recently introduced into the tomb of Henry VII. At the Middle Temple the roof retains the old hammer-beam principle, but instead of one, a double superimposed tier of brackets is introduced, and the lessened size and prominence thus given to the arching mitigates the Gothic feeling. As regards detail, both the Gothic and the Italian forms present at Hampton Court have disappeared. There is no carving, but the mouldings, turned work and panels are all in the manner adopted by English handicraftsmen as their own, but founded on models based-on that Flemish interpretation of the Renaissance which so strongly influenced Thorpe. Approximate in style and date to the Middle Temple roof is that in the hall at Wiston (page 96), which, moreover, is contemporaneous with that at Kirby, completed before Sir Humphrey Stafford’s death in 1575. All, therefore, belong to the earlier years of Elizabeth, as does the hall at Chavenage (page 5), which is now ceiled at the roof plate, but very likely originally was open. Such halls, already exceptional, were entirely superseded by the end of her reign, except in huge houses like Hatfield, and even then the size was not very great. Even before her accession there were halls in fairly important houses that had a storey over them. Such will be found at Parnham (page 14), where the original corbelled out chimney above the hall windows shows that the ceiling is no later introduction, but contemporary with the building of the hall by Robert Strode some time before his death in 1558. Under Elizabeth the normal plan, frequently occurring in Thorpe’s book, was to make the hall a large oblong room of single-storey height, and place above it a withdrawing-room—or “great chamber” as Thorpe calls it. Such there was at Shaw (page 212), completed in 1581; and such there still is at Doddington (page 387), completed in 1600. At Quenby (page 379), the withdrawing-room is a careful replacement of the original arrangement, which was, therefore, still usual in James I.’s reign, when Quenby was built.

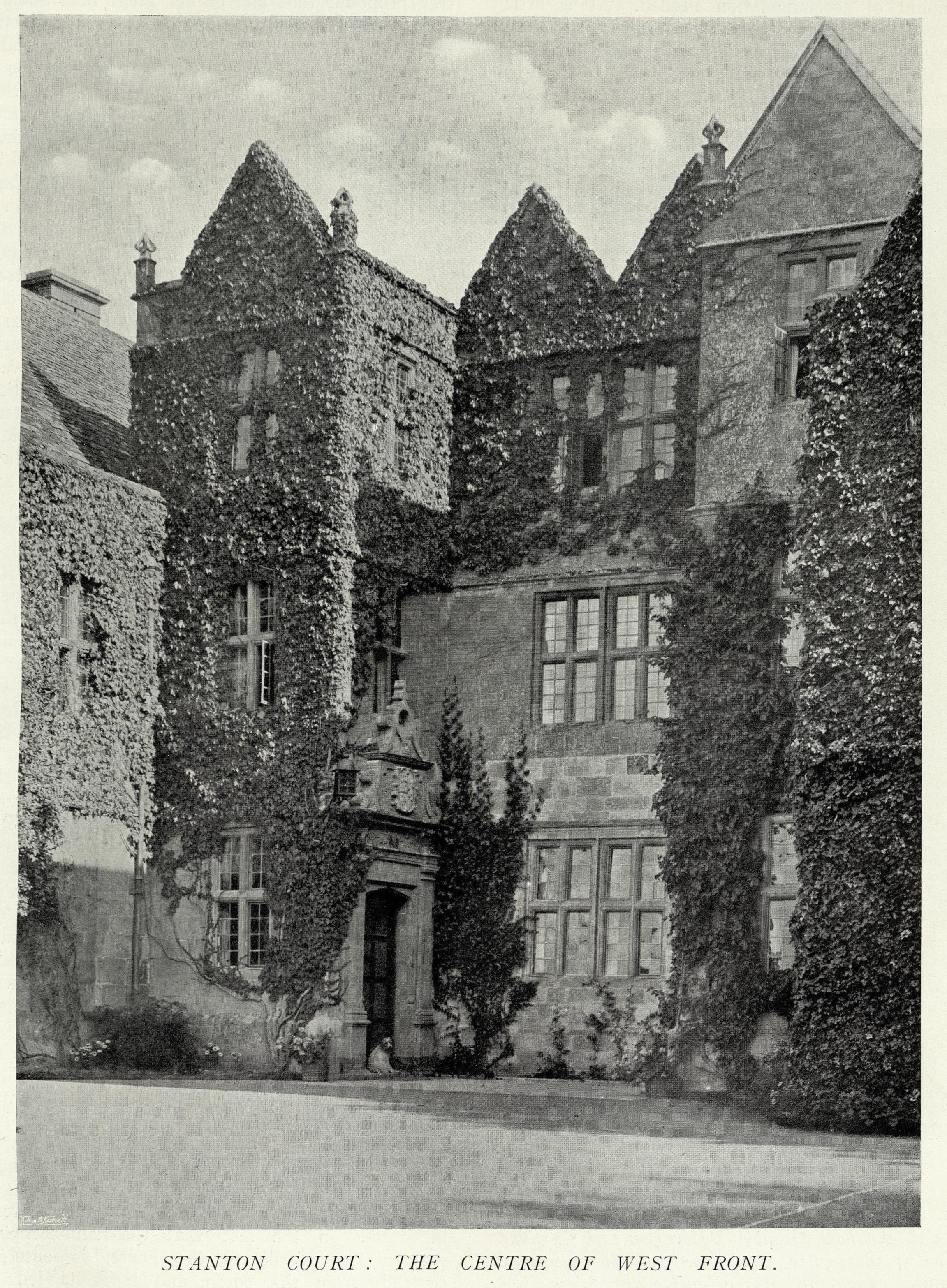

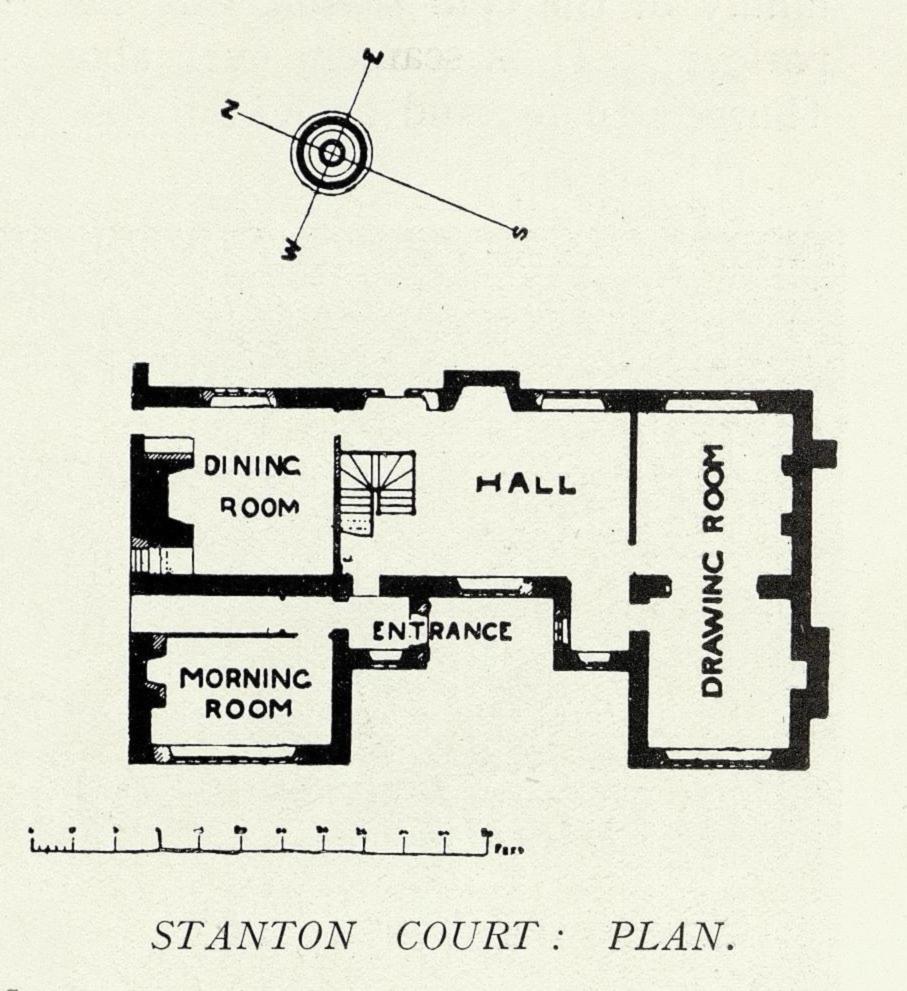

STANTON COURT: THE CENTRE OF WEST FRONT.

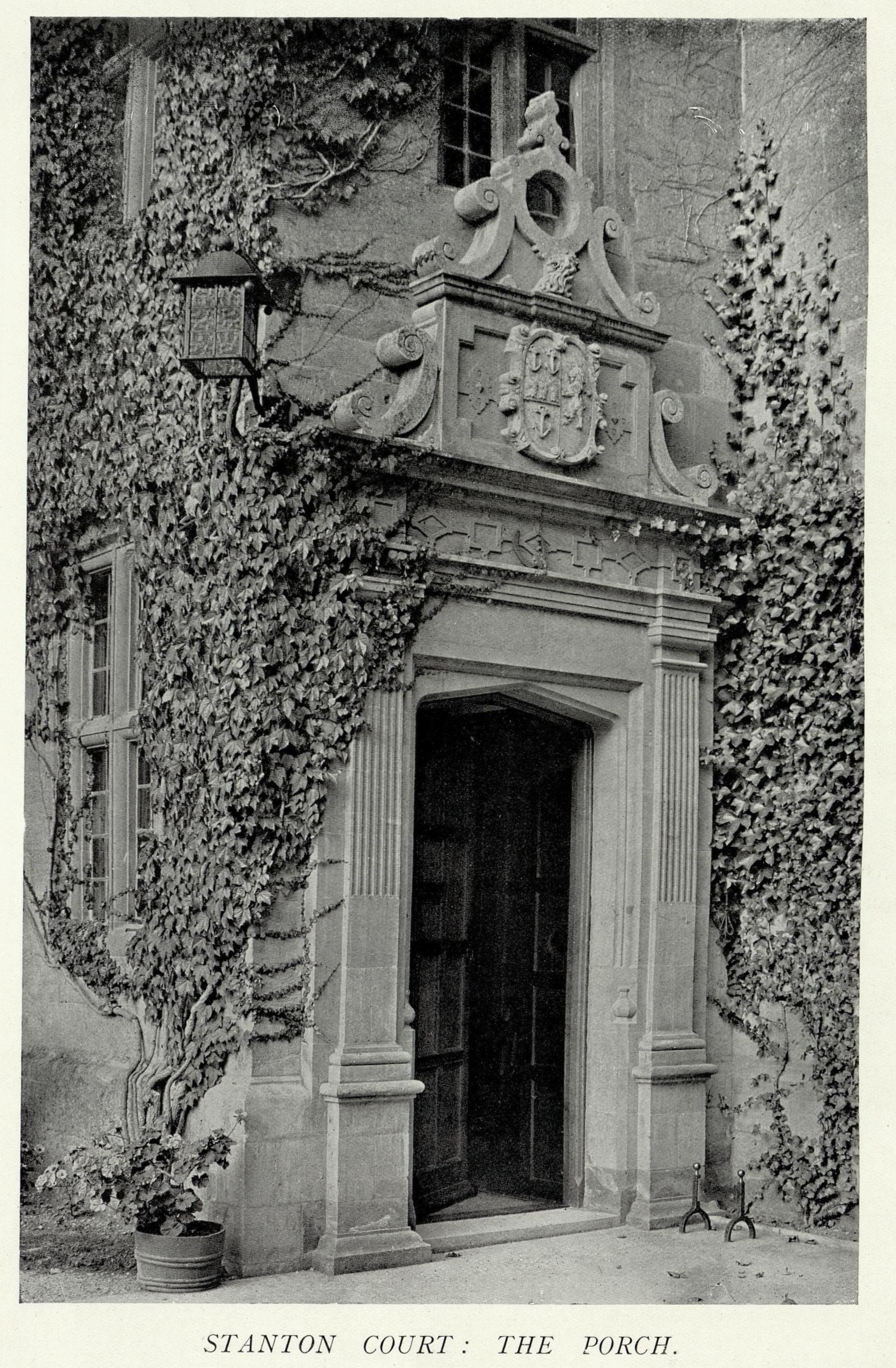

But this modification in size and height did not affect the customary position and general arrangement of the hall. It was still an oblong, of which the width was the width of the central part of the house; it was still lit from both sides and entered from one end through screens, facing which were the office doors, reduced from three to two in most of Thorpe’s plans. This conservatism was apt to create a difficulty in the way of the designer who was imbued with the desire of making his elevation symmetrical, and symmetry was a Renaissance principle that gained early and strong support. Where the lofty hall was retained, its great windows had to be given a counterpart, although such was not called for by the interior arrangement. Thus the old and excellent scheme of an exterior in sympathy with, and telling the tale of, the interior had to be replaced by an architectural trick that told a deliberate untruth. Symmetry required the porch to be central. But inherited habit placed it at one end of the hall. The hall, therefore, could not occupy the centre, but only one side of the elevation, and the subsidiary rooms on the other side of the porch and screens, though they were of different size, height and character to the hall, had to have their windows made similar to it. A glance at the illustrations of the south end of the Kirby quadrangle (pages 70 et seq.) will show that the great, lofty windows of the ruined part lying on the left of the porch are an exact counterpart to those of the hall on the right, although they light small rooms on two floors. The same lapse from truthfulness occurs at Wiston (page 89), but, on the other hand, at Chavenage (page 2) truth is retained and symmetry is wholly ignored. The reduction in the height of the hall lessened the difficulty. But even then the hall was one of an important suite of fairly lofty rooms, while the pantry continued to be placed on the opposite side of the porch. This led to its being overwindowed, as at Quenby (page 372), or to the abandonment of complete symmetry, as at Shaw (page 210). All these are large houses, with long central portions between the outstretching wings. But how could symmetry be attained in smaller houses where the central part was to be no longer than the hall itself, and yet that hall be entered at one end from behind screens? Clearly the porch could not occupy the centre of the elevation. That place was given to the main window of the hall, on each side of which were projections, the one containing either an oriel recess or a staircase, and the other the porch. The doorway to this was set in the side, in order that there should be no break in the perfect balance of the arrangement of windows. Beyond these small excrescences it was usual to bring forward the gable-ended wings, normal at the time. Dorfold in Cheshire and Whitton in Salop are among this not very large class, but there is no better example, now that the original arrangement has been replaced, than Stanton Court. It is a Gloucestershire house of the full Cotswold type, and the picture given below, together with the plan on page xix., fully illustrate the disposition which has been described. At Shipton (page 245) there is the same manner of entering, but a lapse from symmetry, as the porch rises up into a tower and is balanced by no other excrescence.

STANTON COURT: THE PORCH.

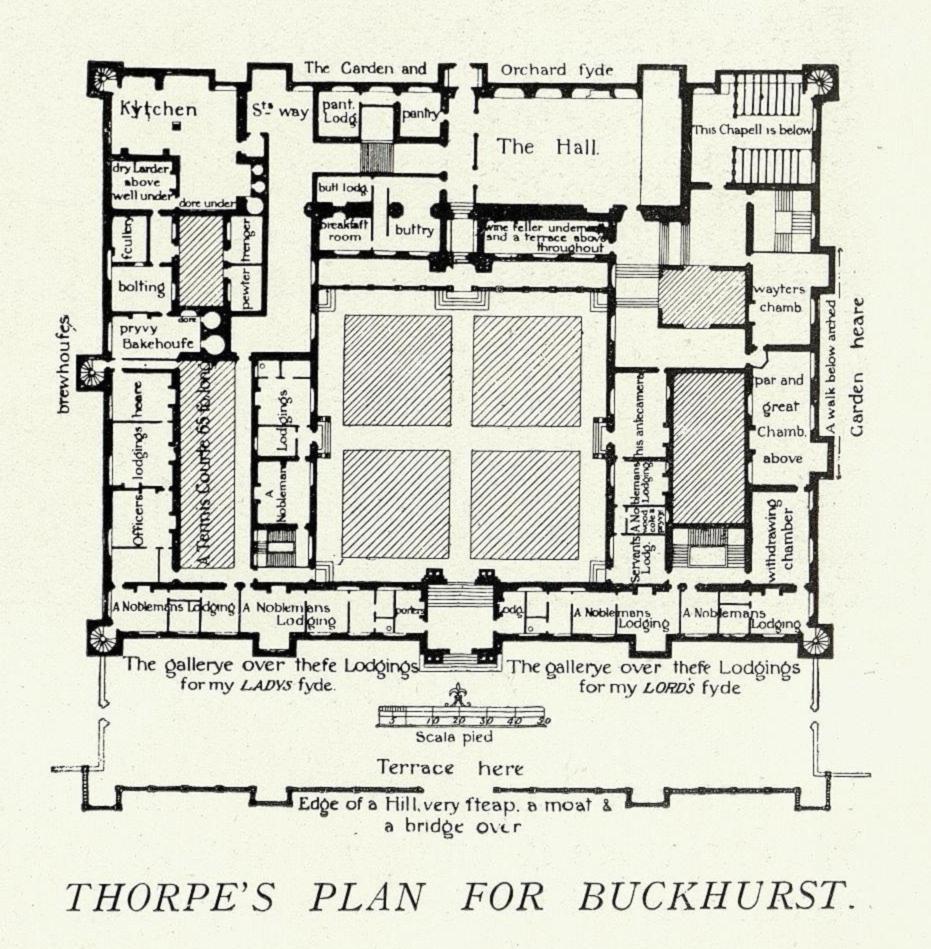

So long as the old hall arrangement was the dominant factor, the house-plan fell naturally into the shape of a narrow centre, with wings more or less out-stretching, according to the amount of accommodation needed. At a little manor like Stanton the wings would not project very far, and only on one side, and thus the E shape arose. But so soon as the scale was larger, the projection would increase and occur on both elevations, making the typical H plan found at Shaw, Quenby, Doddington and Charlton. The quadrangular plan, favoured in mediæval times owing to its defensive qualities, was seldom resorted to, except in very large houses, where, as at Kirby, “lodgings” for married members of the family or for guests with retainers opened direct into the quadrangle, as still do sets of rooms in Oxford and Cambridge Colleges. In bigger manner than at Kirby, Thorpe worked on the same lines in preparing his plan for Buckhurst (page xix.). It never was carried out, but is valuable as showing how an Elizabethan architect proposed that one of her great men should house himself. It forms a parallelogram, with one large central court and several subsidiary ones. Thus the system of narrow roof-spans was retained, while the hall arrangement is quite mediæval, the treble doorways from behind the screen to the offices being in this case retained. But it is clear from the plan that symmetry ruled on every elevation. Another quadrangular plan, but on so small a scale as to make the central court little more than a well, appears on pages 217 and 218 of Thorpe’s book. It is very like that of Castle Bromwich (page 344), and perhaps the likeness was originally greater, as the present first-floor plan may be a later rearrangement. Thorpe, as usual, placed his “great chamber” exactly over hall and porch, and his gallery was at the back of the house. The hall was still lit on both sides, for one window opened on to the court. But as the quadrangular arrangement made one of its ends an outer wall, he lit it with a bay to match two others on that elevation. He was by no means a man to adhere to a cut-and-dry set of plans. He was even fond of freaks, as we see from his scheming an altogether eccentric and uncomfortable plan for a house for himself, taking the form of the letters I T. Probably he was in advance of his clients, who were slow to adopt any new arrangement, and was more than ready to abandon the old hall plan when he got a chance. This was given to him by a certain “Mr. Willm Powell.” Who he was we know not, nor where his house stood if ever it was erected. But plan and “upright” appear on pages 265 and 266 of Thorpe’s book, and the interest in it lies in the fact that the hall occupies exactly the middle of the house, is entered centrally from the porch, and it is its length and not its width that occupies the width of the house. Such is precisely the arrangement we find at Charlton (page 412), which was begun in 1607, so that we shall probably be right in calling this advance Jacobean rather than Elizabethan. Did Thorpe monopolise it and use it at Charlton as well as for “Mr. Willm Powell”? That is uncertain, but there is a plan included in his book which is almost a fac-simile of that of Charlton. There is no elevation and no name, but on it is written “Ld Clanrickarde.” Now, Richard Burgh, fourth Earl of Clanricarde, married the widow of the Earl of Essex in 1601, and through her he became seized of “the South Frith manor in the Liberty of the Lowey of Tonbridge.” There, about the same time that Charlton was building, he erected a house on high ground and called it Somerhill. A comparison of the view of Somerhill as engraved in Hasted’s “Kent” with the ground plan called “Ld Clanrickarde” in Thorpe’s book shows that they both refer to the same house, and though that house was added to and altered in the nineteenth century, the old plan and its disposition can still be traced.

Thus Somerhill and Charlton, both of which we may owe to Thorpe, show the same break with tradition. The shape of the hall gives a greater depth to the central block, and thereby lessens the projection of the wings. Indeed, at Tissington (page 358), which originally was a small house with the same hall plan, there were no wings at all. These houses are a link between the scattered, wide-spreading sets of buildings on the plan which the Elizabethans had received from mediæval times and did not largely alter, and the square, close-knit, two-room-deep houses which, direct from Italian sources, Inigo Jones introduced at Raynham and Coleshill, and which became the accepted model for country residences after the Restoration of 1660. To Charlton, therefore, as marking the close of the earlier manner of planning and designing, is given the last place in this volume.

STANTON COURT: PLAN.

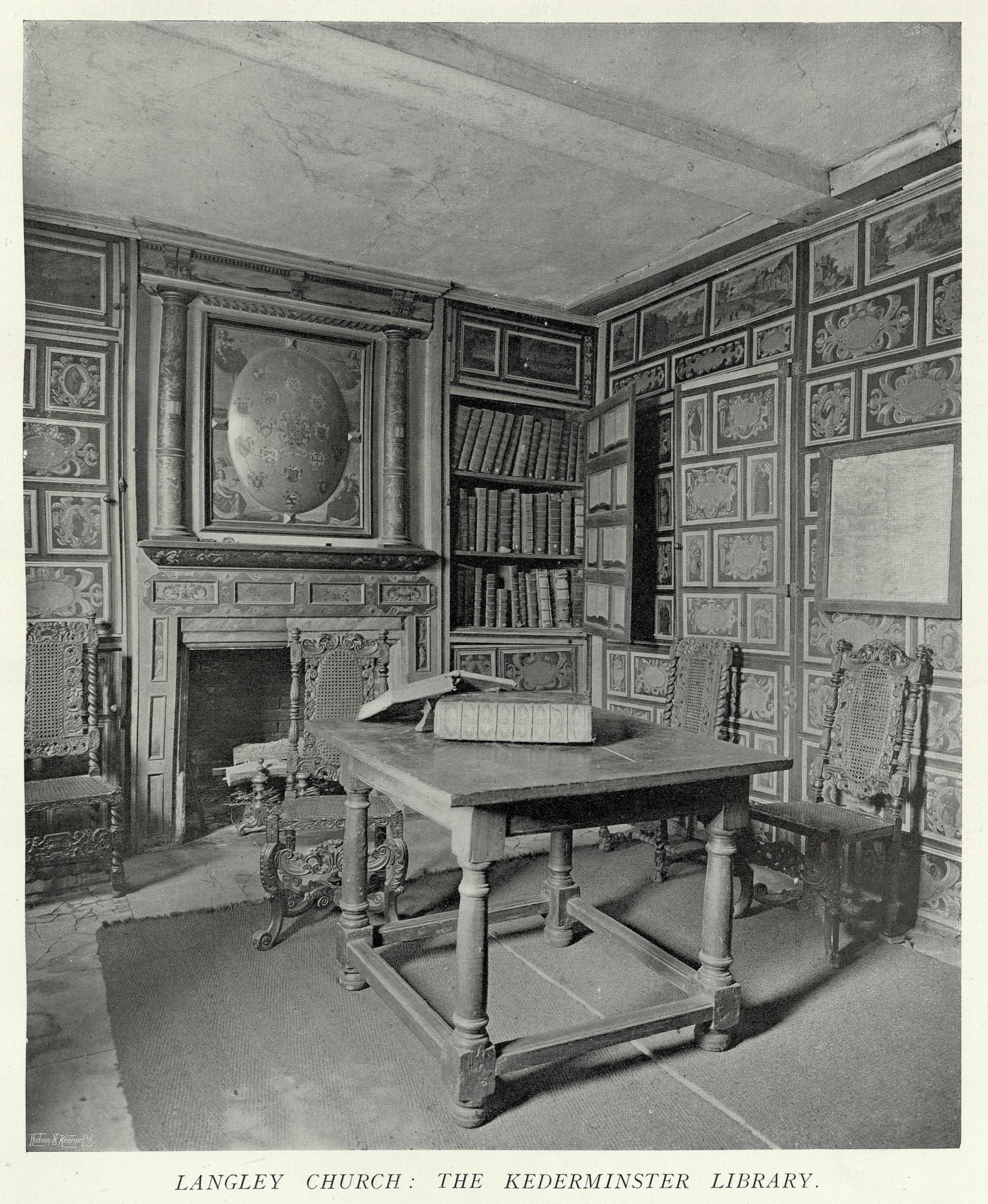

The hall, as retaining well into the Early Renaissance period its mediæval importance, has so far monopolised our attention. Now we must survey those portions of the house which continued to lie on each side of it. Several of the plans in this volume still show something of the old arrangement of the offices. At Salford (page 267) there are still two doorways on the right of the screen, though they no longer admit to pantry and kitchen passage.

At Shaw (page 212) the pantry retains its original place, but its door must have been blocked up. At Quenby (page 378) what was the pantry arid another small room have, together with the kitchen passage, been made into a new dining-room, but the old arrangement appears on the plan made in 1790, although by that time the door from the screen passage had been blocked up as at Shaw. In all these cases there no doubt existed the disposition usual in Thorpe’s plans, as shown by those of Buck-hurst on this page and of Kirby (page 74). At Buckhurst both pantry and “buttry” remain, and so there is the full mediæval arrangement of three doorways, the central one, opening into the kitchen passage, being larger than those that flank it. At Kirby, ample as is the house, one of these subsidiary offices is abandoned, as was customary under Elizabeth, that which was retained being always called not pantry, but buttery. Being used by the butler or boutillier, it had in it steps to the cellar, as we see on the Kirby plan and as they still exist at Charlton, where, however, the old cellar is now the muniment-room and the buttery a lavatory. The second door from the Kirby screens leads eventually to the kitchen, which, however, is reached through a servery or store-room, then always styled a “survaying place.” The kitchen has two great fire-arches, ten and twelve feet across respectively. In smaller houses there would be only one, but a twelve-foot span was by no means large for it, as we may judge from the illustrations of those at Plas Mawr (page 128) and Quenby (page 384).

THORPE’S PLAN FOR BUCKHURST.

Within the arch was a small brick oven, but it was normal to have two very large ones in a room beyond the kitchen seen in the Kirby plan and generally termed the “pastry” or bakehouse. Larders “wet” and “dry” would complete the customary indoor office accommodation, except that there was habitually included within this section of the house a warm, sunny, family living-room handy for the housewife, who spent much time in the kitchen and with her maids. These were the days of home industries—of home brewing and distillation, of home curing and baking, of home production of monumental cakes, pasties and sugar-work constructions. The lady of the house was expected to do more than give the cook orders.

“The tables were newly covered with costly banquets, wherein everything that was most delitious for taste prooved more delicate by the arte that made it seem beauteous to the eye; the Lady of the house being one of the most excellent Confectioners in England, though I confesse many honourable women very expert.” Such is the description by an eye-witness of the preparations made in 1603 to entertain James I. at Apethorpe, which is close to Kirby. The room which such a lady would often use, and which seems to have been much frequented by the family in the cold season, was called the “winter parlour.” It is scarcely ever absent from any of Thorpe's plans, and at Kirby was entered through the left door at the end of the kitchen passage. We can trace it under a different name in many a recent plan of a home of this period. For instance, it is the housekeeper’s room at Castle Bromwich, the gunroom at Shaw and the dining parlour in the Quenby of 1790.

CHELVEY COURT: THE STAIRCASE.

Where, in Thorpe’s plans, there is also a dining parlour—for the hall had ceased to be used for such a purpose except on an exceptional feast day—it is one of the principal downstair rooms reached from the other or upper end of the hall. Judging from its position in the house plan “for Mr. Willm. Powell” already alluded to, it would have been what the 1790 Qaenby plan calls the withdrawing-room, while at Shaw it has retained its name and use.

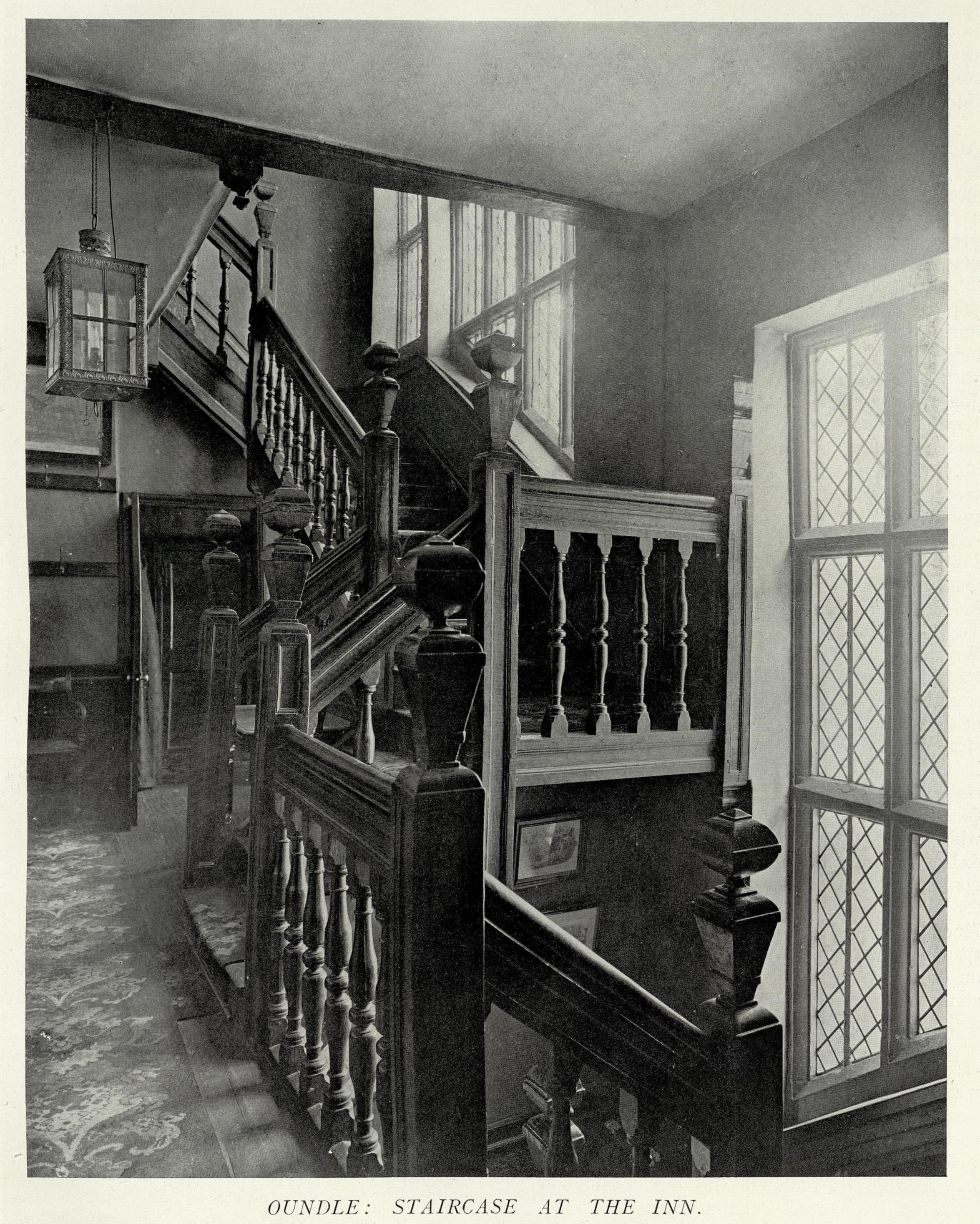

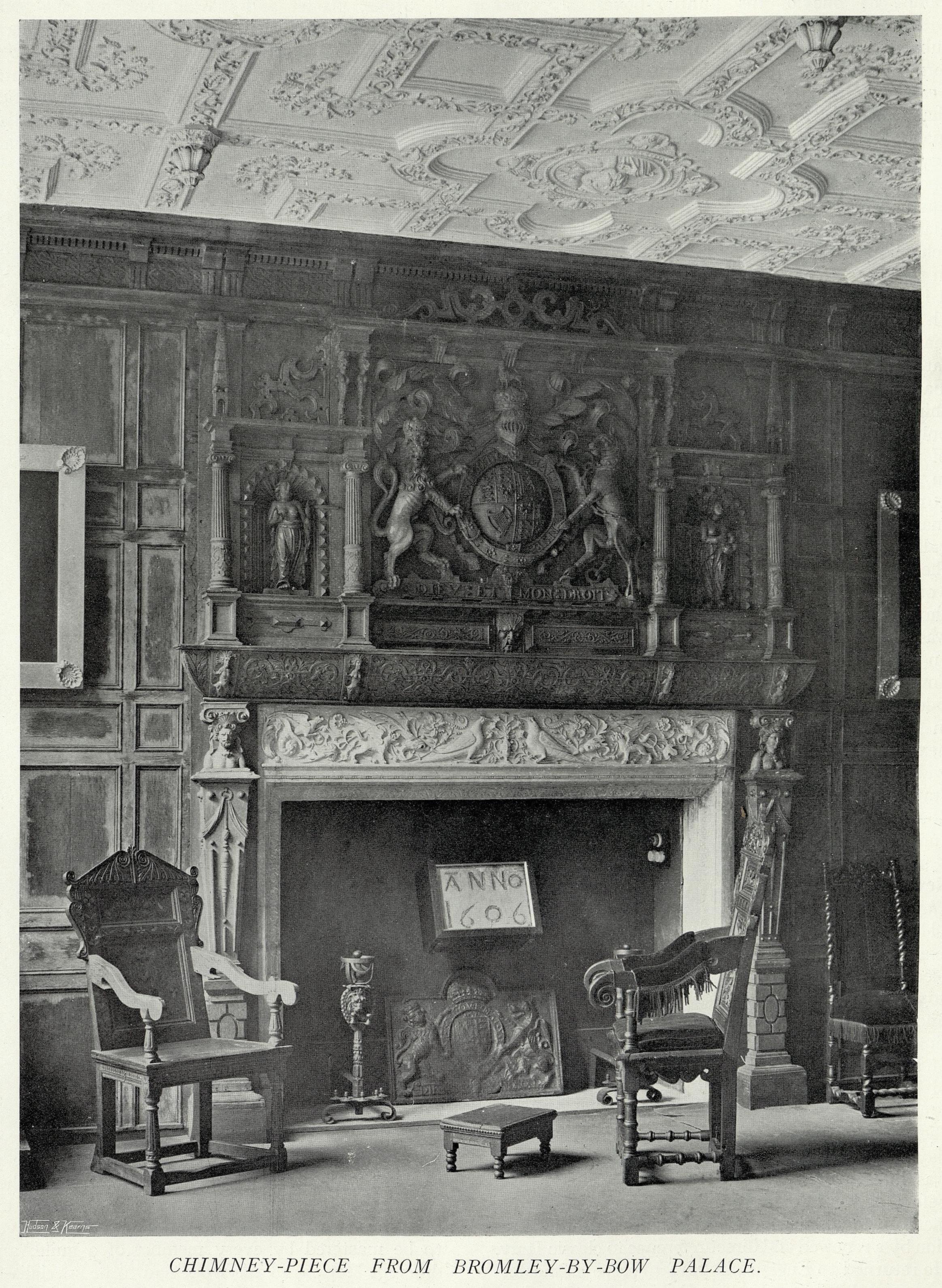

OUNDLE : STAIRCASE AT THE INN.

In both these house plans it will be seen that the great staircase is placed between the two downstair rooms, of which one was the dining parlour. That was the most normal arrangement, and thus we find it placed in various houses included in this volume—at Doddington and Tissington, at Breccles and Broughton. At Castle Bromwich the quadrangular plan causes only a slight variant. No part of the house was more revolutionised in the sixteenth century than the main stairway. The winding newel form, sometimes of wood but more often of stone and never very wide or easy in gradient, had persisted through the fifteenth century as the exclusive type, and continued in Elizabeth’s time as one of the forms for subsidiary stairs, such as that at Breccles illustrated on page 45. But even before Thorpe’s time there was a disposition to make one stairway—henceforth to be called the “great stair”—adequate to its purpose of leading up to the withdrawing-room or “great chamber” which was being placed over the hall. Instead of a winding and continuous ascent it was sometimes placed in a square compartment and made, as at Salford (page 267), to work round a small, central enclosed well in a series of short flights and landings. Or it was composed of two longer flights rising up to and away from a single half-landing, such as we see it at Breccles (page 44). Here, too, it was enclosed and composed of solid oak treads. Soon, however, its decorative possibilities were recognised, and it mounted around an ample open space and had ornamental newel-posts, balusters and strings. The staircase at Chelvey (page xx.) has exactly the same arrangement of short flights and landings running round a square as that at Salford, but it is on a much larger scale, and the central well being left open, massive turned balusters and panelled newel-posts topped with great balls are introduced, with the result that an air of rich dignity and spacious ease is given, although there is no carving or other ornamental elaboration of the woodwork. The Chelvey staircase probably does not date before the reign of James I., and its simplicity comes from its being in a house built by a Somerset squire of no great fortune or position. Long before that men of wealth and leading, employing the best foreign or native craftsmen of the day, had given to their staircases the richness of carving which characterises Elizabethan woodwork. Such was the stair (page 86) that Thomas, Duke of Norfolk, introduced into The Charterhouse shortly before his execution in 1571. The carving is excellent in design and execution, and has rather more of the Italian flavour than most Elizabethan work, which generally saw Italian Renaissance ornament through Flemish spectacles and then gave it a native interpretation. Such we find at Charlton (pages 408 and 409), where flat strap work is the leading motif, while at The Charterhouse, though the strings are in this manner, the posts have ribbons and groups of implements introduced into the scrollwork.

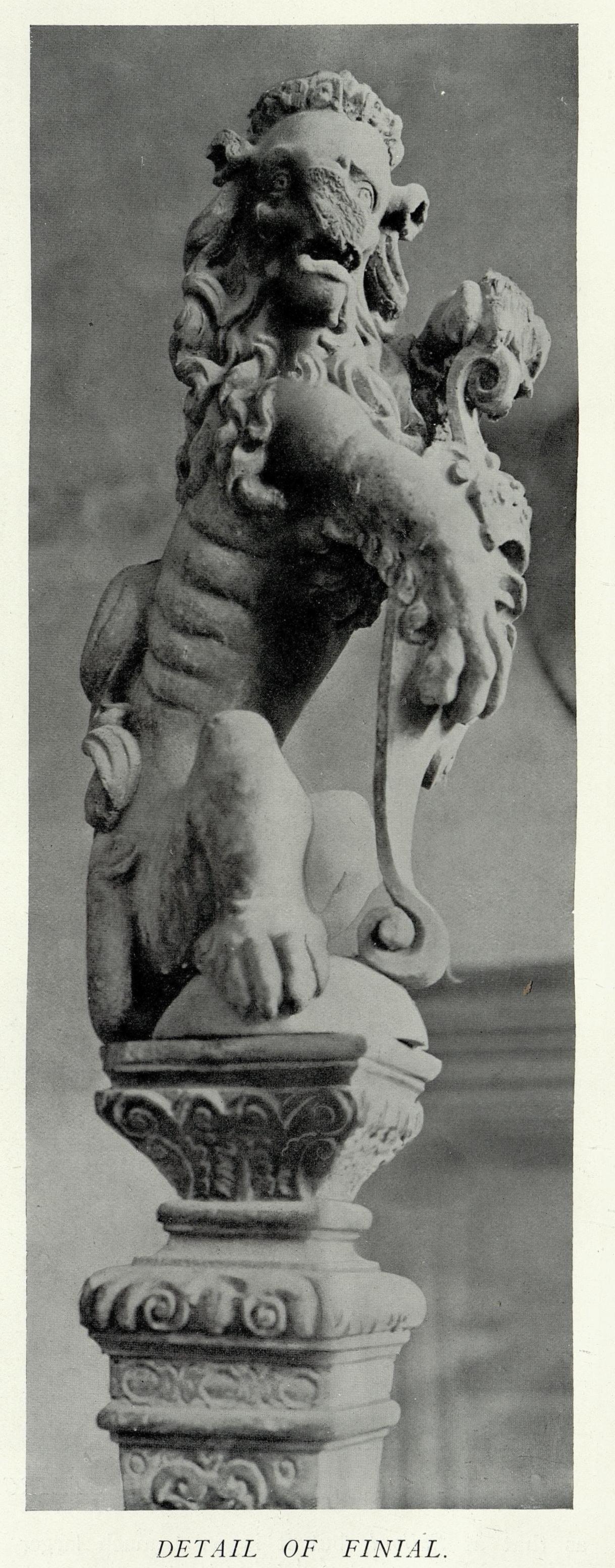

At Charlton the original finials are wanting. At The Charterhouse they are of tall vase shape, topped by a crest. Newel finials of the same form but surmounted more ambitiously are to be found on a rich though small staircase illustrated on this page and the next, and now existing in a much-decayed little manor house. Heraldic “beasts” holding shields or a flag were extremely popular as stone finials to gables or on garden posts during the reign of Henry VIII., who used them largely at Hampton Court. They remained popular with his children, and even into the reign of James I., when the Earl of Dorset placed them at Knole both in stone on his gables and in wood on his newel-posts. But it is curious to find such remarkable examples in a little house, and the whole staircase may have been an introduction from a more sumptuous abode, just as the Staircase (page xxi.) now in the Inn at Oundle is reputed to have come from Fotheringhay. The “beasts” may have come from another Royal domicile, as they are Royal supporters holding shields with Royal emblems, such as a Tudor rose crowned. The presence of the Welsh dragon, which Elizabeth was the last to use, together with the unicorn which James I. adopted, seems to place the date at about 1603. The carving of the posts, string and balusters is all of the flat strapwork kind used at Charlton, which dates from half-a-dozen years later. Modest staircases of much charm and some richness will be found at East Quantockshead (page 318) and Tissington (page 366), while that at Quenby (page 377) is, like the Chelvey example, ample, but plain. There the newel-posts continue up, wherever there is structural reason for it, as a column supporting an upper flight. Much the same device was resorted to at Chilham (page xxiv.), where it is combined with an arcading—an infrequent though charming finish to such a staircase, of which one of the best examples is that at Knole.

DETAIL OF FINIAL.

The size and sumptuousness of the great staircase was of much importance because of the ceremonious use that was habitually made of the first floor of houses. In the more palatial houses, such as Burghley and Knole, the Italian mode of placing the whole of the reception suite over a lower storey was resorted to, although this did not become a habit until the Later Renaissance period. But in much humbler houses it was usual not merely to have a “great chamber” over the hall, but also an upstairs gallery. This was the most marked and extensive of the Elizabethan innovations. Thorpe introduced it into very moderate-sized houses, and in large ones gave immense space to it. At Kirby it occupied the first floor of the west side of the court, and was one hundred and fifty feet in length. In his plan for Buckhurst the whole of the first floor of the entrance side of the great parallelogram was given up to a gallery over two hundred and fifty feet in length, but divided into two, the halves being marked respectively “for my Ladys syde” and “for my Lords syde.” This “vast pile,” as Horace Walpole afterwards called it, believing it to have been built, never got beyond Thorpe’s drawing board. But in the real Buckhurst, a house of older date, there was a gallery. This is of importance, as showing that such an apartment was included in the house of a well-to-do country squire even before Elizabeth ascended the throne. Mr. Gotch, on page 197 of his “Early Renaissance Architecture in England,” after stating that "at Hampton Court in the time of Henry VIII. and Jane Seymour there was the Queen’s long gallery, which was 150 feet long and 25 feet wide,” adds : “But although the palace had such an apartment there is no evidence that the smaller houses in general possessed them until the time of Elizabeth.” “In general” no doubt they did not, but that they existed and were considered normal is clear from the will of John Sackville, who died in 1557. As the gatehouse tower, which alone survives of his buildings at “Old” Buckhurst, has the pomegranate, together with the rose and fleur-de-lys, among its sculptured ornaments, it would seem that John Sackville, who succeeded to Buckhurst in 1524, did his building while Catherine of Aragon was still Henry VIII.’s undisputed and honoured wife. If so, his gallery would be earlier than Jane Seymour’s at Hampton Court. In any case it must date from some years before Elizabeth’s accession. In his will he mentions his gallery in connection with the right which he bequeaths to his widow to use his “newe chambers” so long as she lived, and have free access for herself and her servants to the kitchen and the garden, the gatehouse and the chapel, the latter being approached through the “Gallarie.” This not infrequent arrangement of a widow having a legal right of retaining for her use part of the chief family home after it had passed into the possession of her husband’s eldest son continued into the seventeenth century, and there are other cases of the right including access to the gallery. The Sackvilles owned the estate of “Sheffield” in Fletching parish some miles south of Buckhurst. Of Sheffield Place John Wilson, ancestor to the present owner of Charlton, became tenant in 1620. Dying twenty years later, he left to his wife, besides plate and linen and “two of my best beds all furnished,” full possession of two bedrooms — one being “the chamber wherein we usually lodge” — “with free libertye of access e egresse & regresse in and to and from the said roomes at all tymes for her & her servants, with lyke libertye to walke and recreate herselfe at all tymes in the gallerye.” Here we get mention of one of the uses to which these extremely long but often very narrow apartments were put. They were the ladies’ promenade in bad weather. At Charlton House in 1644 took place the love-affair between Anne Murray and Thomas Howard shortly related on page 407. In her full account of it she says she “did give him liberty one day when I was walking in ye Gallery to come there and speake to mee.” No doubt galleries had many other uses. In that at Apethorpe there is incorporated in the great mantel-piece a figure of David playing the harp and an inscription dedicating the spot to the Muses. Like most girls of her time, Anne Murray had been taught, besides writing and French, all kinds of needlework, and also to dance and “play on the lute and virginals.” These probably are the same “2 severall Instruments” that were being taught a few years later to the grand-daughters of John Wilson of Fletching. Besides walking and music and dancing, the gallery in large houses was generally arranged to be one of the suite of principal rooms used for receptions. At Charlton it communicates through another room, and also across the chief landing, with the withdrawing-room. At Castle Bromwich it is next to the upstair drawing-room, while in Thorpe’s similar plan it is, as at Charlton, entered from the opposite end of the chief landing, and occupies the whole length of that side of the house. But in many houses sufficient accommodation for it could not be given on the first or principal floor, and it was located above. At Quenby and Doddington it ran from end to end of the central block of the house, that is, over the withdrawing-room and the rooms next it. Here, the roofs being flat, the galleries were of fair height and had straight walls. But in gabled houses they went up into the roof as at Broughton (page 325), or were wholly accommodated within it as at Salford. Such a space, when existing unused in a mediæval house, was often transformed into a gallery by the Elizabethan owner, as by Waldegrave at Hever.

STAIRCASE WITH HERALDIC NEWEL FINIALS.

CHILHAM CASTLE: THE STAIRCASE.

The withdrawing-room over the hall is habitually called by Thorpe the “great chamber.” The name came down from mediæval times, when an important upstair room in great houses would be used on ceremonious occasions for reception, although it contained a bed. The custom of receiving in the bedroom long continued in England, and still exists in France. The magnificent carved oak beds of Elizabeth’s day, such as the one at Derwent illustrated on page 275, and the extraordinarily sumptuous and costly ones in silks and cloth of gold of Jacobean date, such as that on which Richard Sackville, third Earl of Dorset, is said to have spent eight thousand pounds, were not intended to be hidden away. That a family made common use of the “chamber” of the heads of the house is seen from the account of an affray which took place in 1534 at Ufton, an old Berkshire house, of which more will be said when we come to speak of special arrangements made in houses belonging to Catholics. Ufton then belonged to Richard Perkins, against whom his neighbour at Alder-mast on, Sir Humphrey Forster, had a grudge. One morning the latter “riotously entered” Ufton, found the whole family breakfasting in the parents’ bedroom and accosted Richard with “Abbomynable othes.”

As regards the great room over the hall, however, there is nothing to show that it was usual to place a bed in it in Thorpe’s time. The number of “chambers” in a house had been increasing since the fifteenth century, and so, as most people “lay” with one or more bedfellows, it became decreasingly necessary to place beds in rooms dedicated to day uses. Of course, where so much of the first floor was taken up by reception-rooms, there was not much space left there for chambers, and so, especially where there was only an attic above, we are apt to find them on the ground floor. Thorpe nearly always has some downstair “lodgings” even in small houses, while at Kirby his arrangement of them is alluded to on page 74.

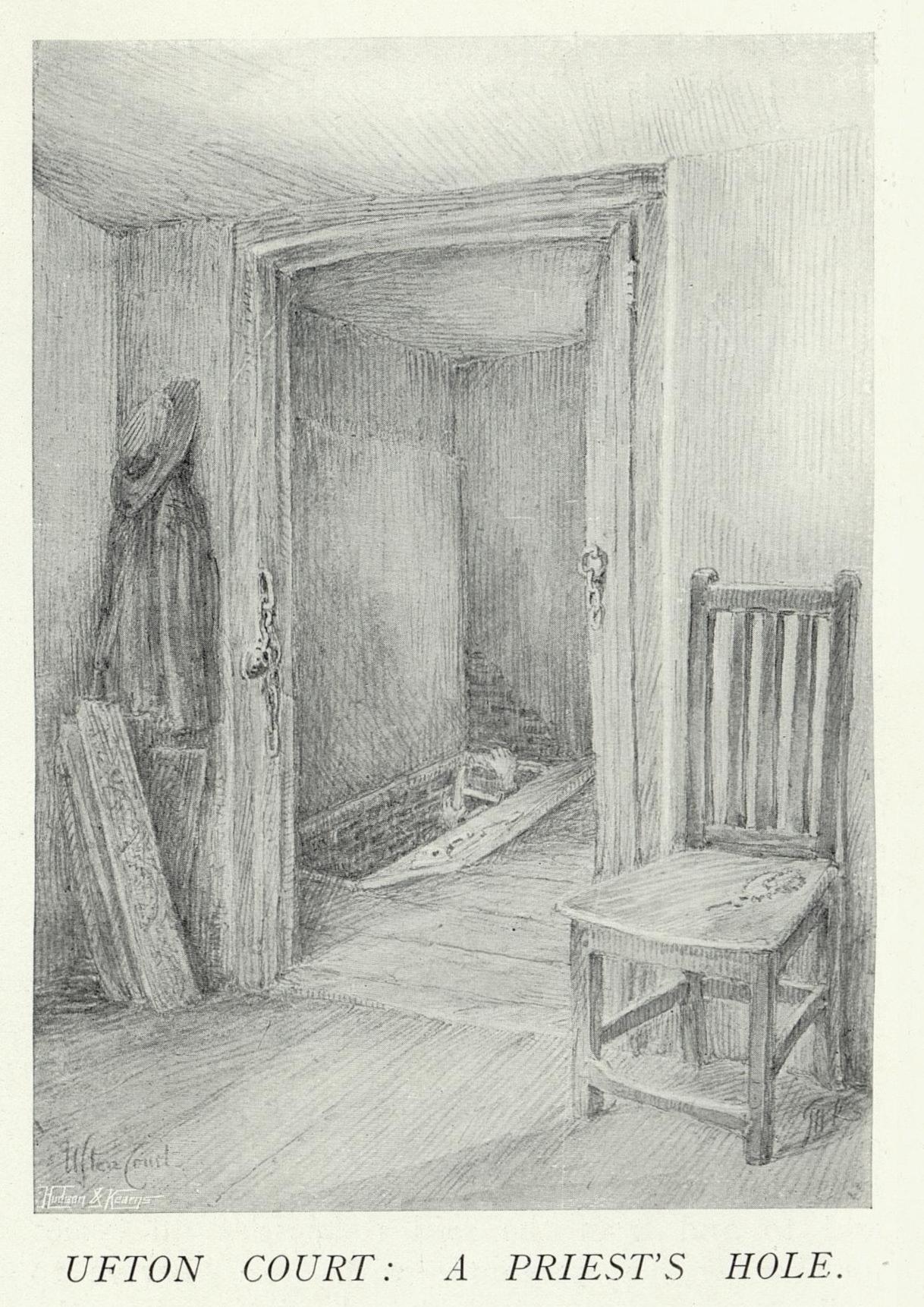

UFTON COURT: A PRIESTS HOLE.

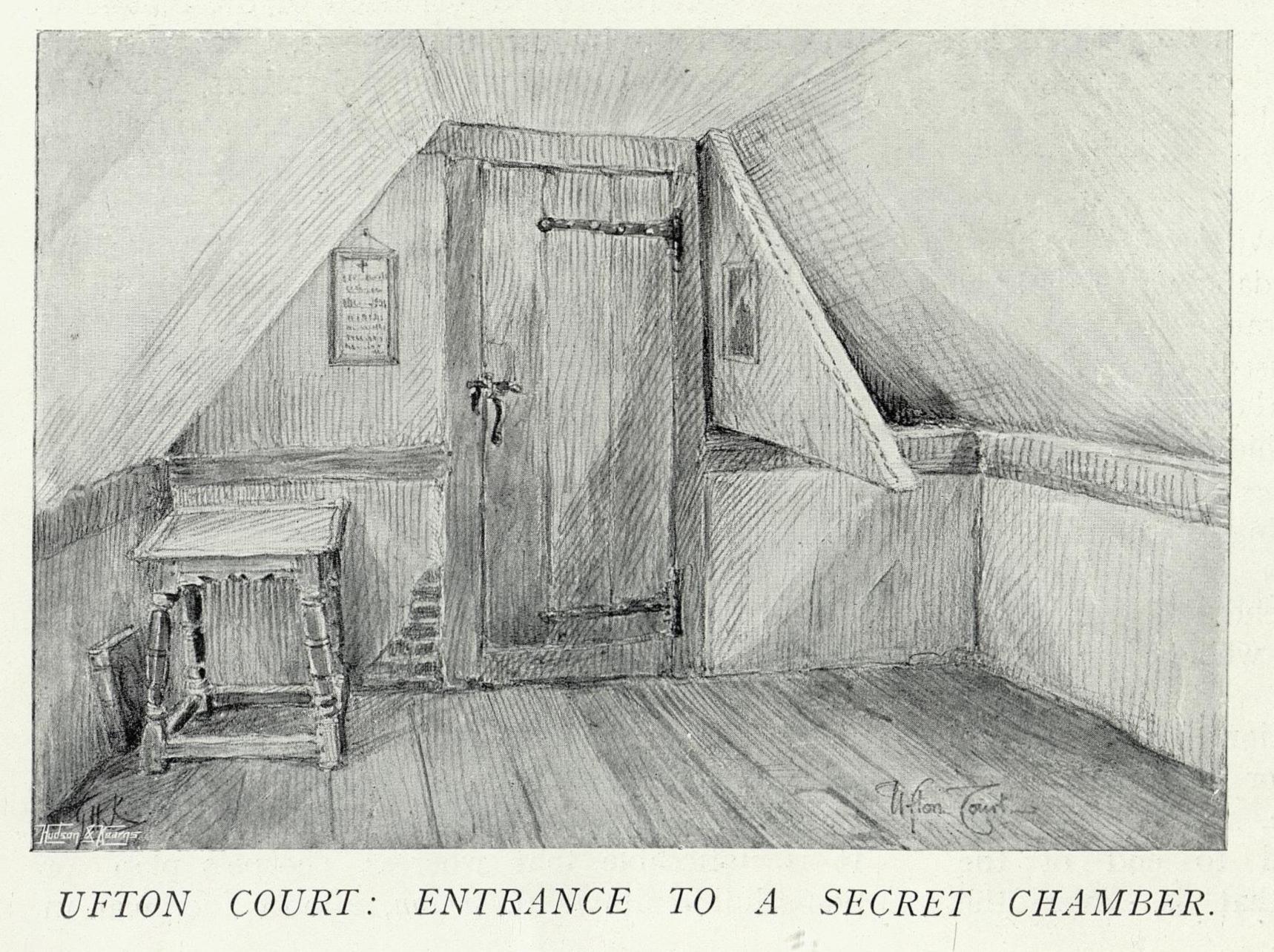

UFTON COURT: ENTRANCE TO A SECRET CHAMBER.

If the Elizabethan house plan shows many additions to that which obtained previously, it tended, in one instance, to an omission. Before the Reformation a chapel was one of the most recognised and important adjuncts to a house of any pretension. But Thorpe habitually left it out, except where he planned ambitiously, as at Buckhurst. Great noblemen must needs have a chaplain among their household, and therefore their houses, such as Burghley, Hatfield and Audley End, of course had a chapel. But it formed no part of the normal manor house plan of the Early Renaissance period. It is noticeable that whereas Thorpe’s plan for Somerhill omits it, Charlton, almost identical in disposition, has one. The builder, Adam Newton, be it observed, was, though a layman, Dean of Durham. He was also tutor to King James I.’s heir, and James was a believer in religious ceremonial, and made bishops of men like Laud. His views would certainly also be reflected by those into whose charge he placed his son. Charlton, therefore, is very much one of those exceptions that prove a rule. Burford (page 223) is another. There was no chapel there, so far as we know, until it belonged to Sir William Lenthall, and he as Speaker of the House of Commons no doubt thought, Commonwealth man though he was, that a chapel agreed with his office. As a rule, however, the type of house illustrated in this volume had no chapel unless it was occupied by adherents of the old faith. But in that case, instead of being an outstanding and noticeable building, as at Burford, or one of the considerable rooms in the house, marked out by a special window as at Charlton, it was hidden away in a remote corner, and except for removable gear did not confess its purpose. Such there was at Breccles, and also at Ufton, where we have seen Richard Perkins assaulted by Humphrey Forster. The rambling nature of Francis Woodhouse’s additions to Breccles and the troubles his third wife’s sympathy with Jesuit priests brought upon him may be read on pages 42 and 44. Not only a secret chapel, but secret accesses thereto and secret hiding-places for the proscribed priests had to be devised, and so Romanist houses of the Early Renaissance period were apt to be partially planned in an abnormal manner. As with Francis Wood-house at Breccles, so with Francis Perkins—a nephew of Richard—at Ufton. He was a strenuous adherent of the older faith, and was determined', to have it exercised under his roof at all risk of pains and penalties. Under his roof not metaphorically merely, but practically, for that is where the chapel is, reached tortuously through rooms and passages and up an unexpected staircase. Secret cupboards, priests’ holes, hidden apertures occur at intervals. Two of these devices are illustrated on this page; one is the section of the wall of an attic which, by means of a spring and a pivot, opens and gives access to a place of concealment; the other is a trapdoor in the floor fitted with a quaint spring fastening within, and whence a ladder leads down into a dark and narrow enclosure. At the very other end of the house a bedroom cupboard connects with a well-like hole which debouched into a subterranean passage leading out of the house, under the terrace, and ultimately permitted escape into the woody declivities to the north. These devices were not only used, but served their purpose, for more than once search was made, but no priest was caught. This was fortunate for both priest and layman, for to be found on English soil in Elizabeth’s day was high treason for a popish priest, and he who harboured him was imprisoned at the Queen’s pleasure. Fines, heavy and frequent, were ever threatening the recusant, and of these the informer got half. So a tailor in the next parish thought it would be more interesting and profitable to spy into the Ufton comings and goings and listen to the gossip of the country-side rather than to sit ever cross-legged at his needle. There followed domiciliary visits by magistrates and reports to the Secretary of State. Francis was absent, but they “made search in his studdy, closette and all other secreate places,” with the result that they found “nothinge contrary to the Lawes,” and the tailor went back to his board with an empty pocket. This was in 1586 ; but in 1599 came another and more serious search. Upon information received at headquarters that great treasure “to be employed to some ill-purpose” was certainly hid at the Court, if not also two “notorious Traytors,” it was determined to take action, the house being “reputed to be a common receptacle for priestes, Jesuytes, Récusantes and other such evill desposed persons.” Accordingly, Sir Francis Knollys with a party of men went to Ufton in the dead of night. Again Francis was away (he seems to have been a man of some prudence and foresight in these matters), but his cousin Thomas was in charge, and opened all doors but one, of which he claimed to have no key. A vigorous kick remedied this deficiency, and revealed the chapel full of “popische Trashe.”

The “secret place” was also opened up, and hence was extracted a ”poke mantua” containing divers “bagges of gold.” But though there were traces—such as half-burnt candles on the altar—that mass had recently been said, there were no “notorious Traytors” to be found. Perhaps the well cupboard and subway had proved opportune.

POSTLIP MANOR : FROM THE SOUTH-EAST.

Enough has now been said of the plan of the Early Renaissance country house in England to enable the reader to understand the character and uses of its component parts. He will also have gathered a general idea of the social habits that led to their adoption. It will now be well to glance at the subject of design and see what were the typical forms and features adopted for such a house.

BROADWAY: FRONT OF “TUDOR” HOUSE.

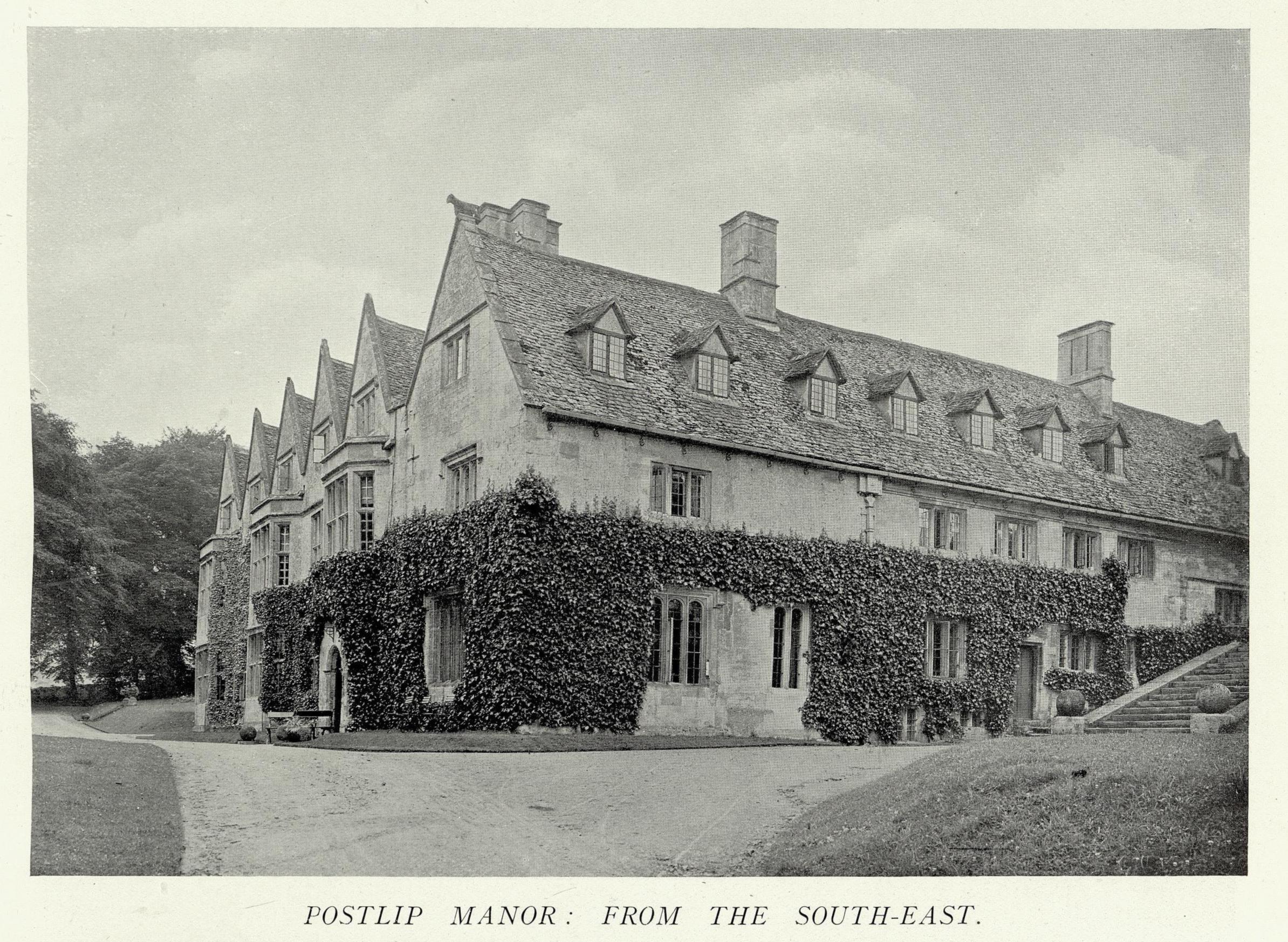

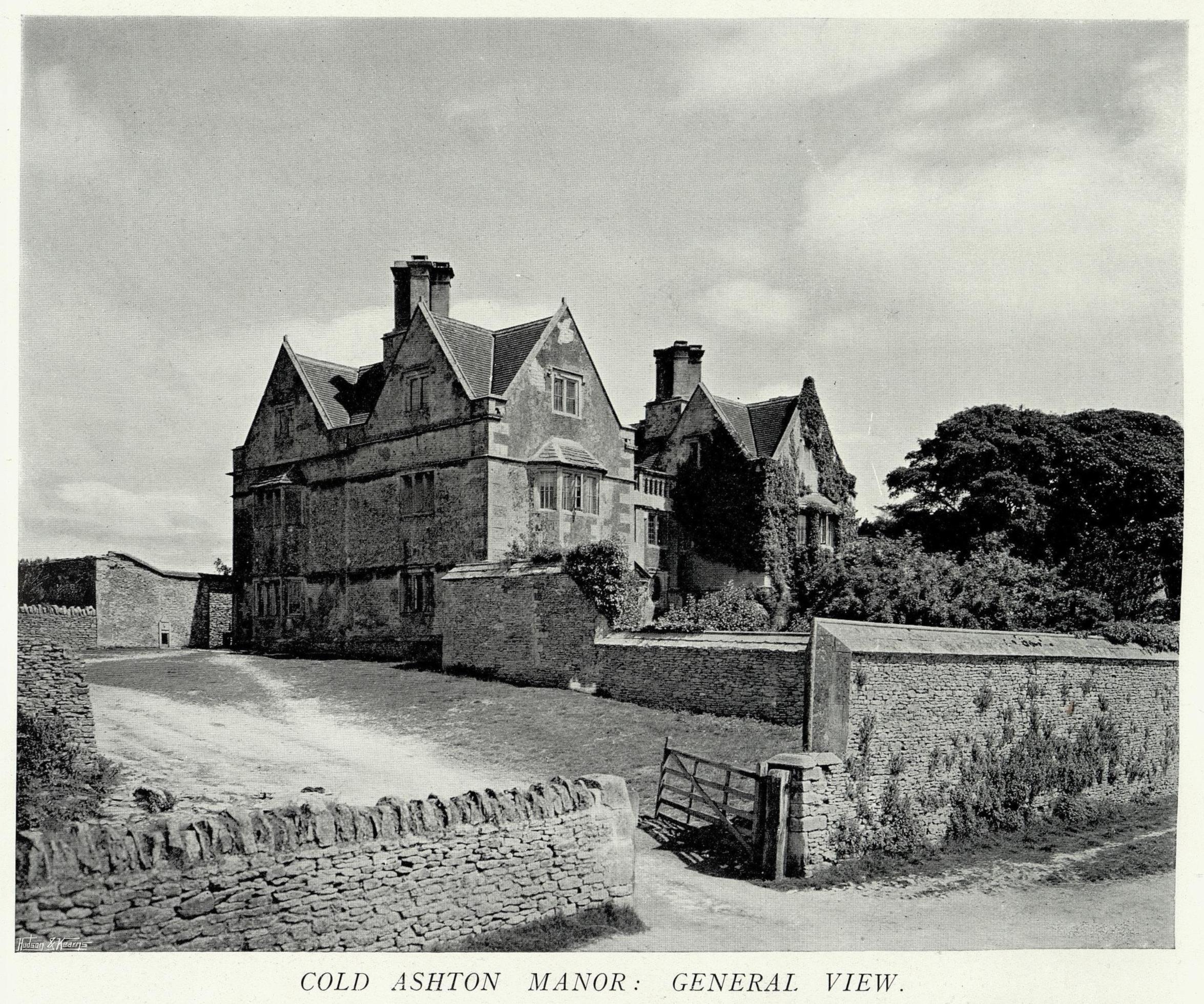

What we shall find, speaking generally, was a grafting of foreign twigs upon a native stock. The sturdy English oak which played so large a part in construction is typical of the attitude of the English sixteenth century craftsman towards the Renaissance onset. For details of embellishment he was, indeed, willing, and often eager, to take what the Continent sent to him. But for structural methods and shaping of the mass he relied upon his home teaching. He retained high-pitched gabled roofs spanning narrow, much-spreading buildings; chimney-stacks, massive, many-shafted and often used as architectural features projecting from exterior walls; windows that have, indeed, lost the arch and the tracery, but retain the structural mullion and transom. At first the treatment of the gable is little altered from the fifteenth century. In stone construction it is coped, the moulded coping rising unbroken from kneeler or parapet to apex, as at Bibury (page xxx.), Postlip (above), Cold Ashton (page xxxiv.), and, indeed, passim throughout this volume.

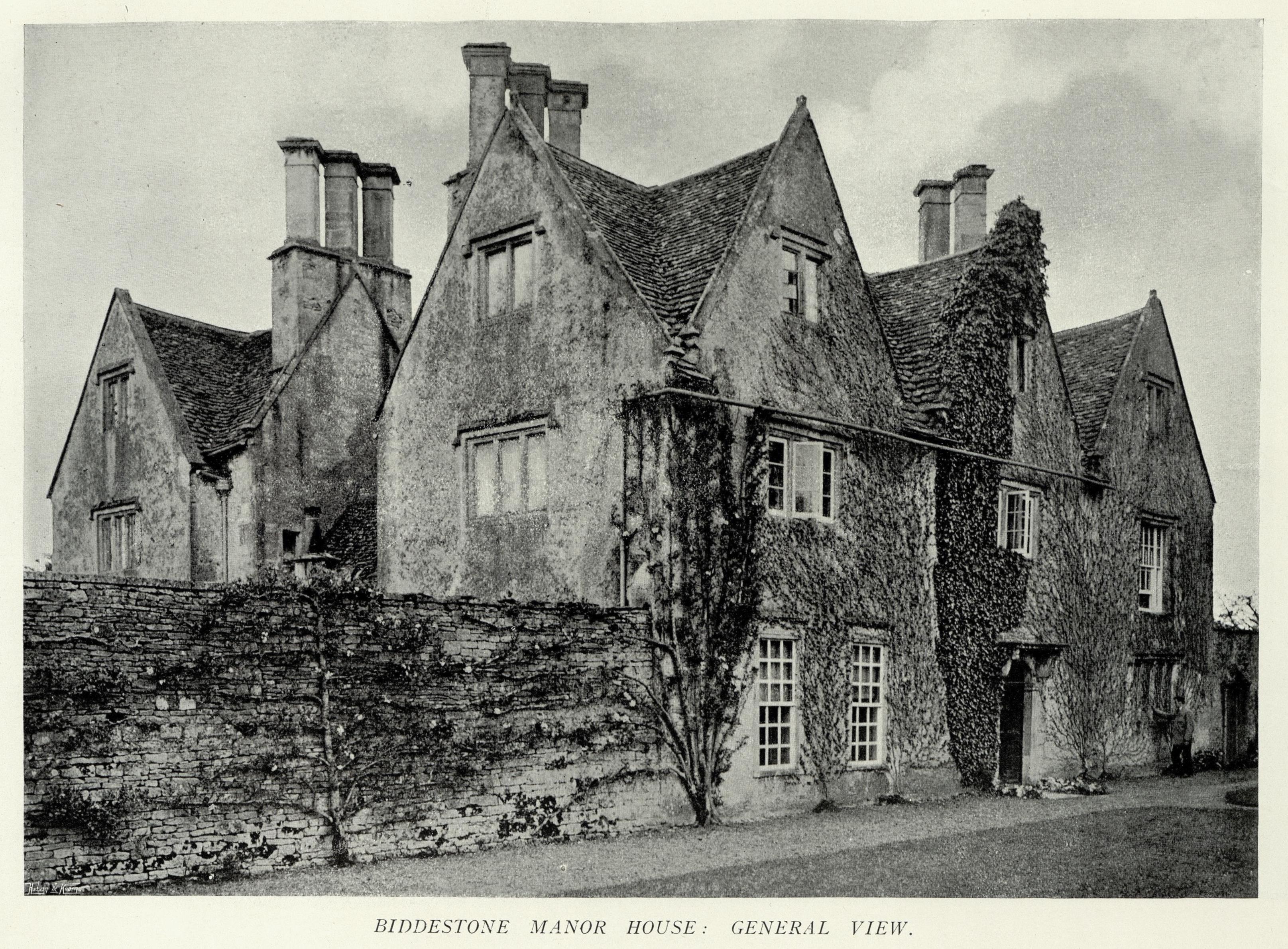

BIDDESTONE MANOR HOUSE: GENERAL VIEW.

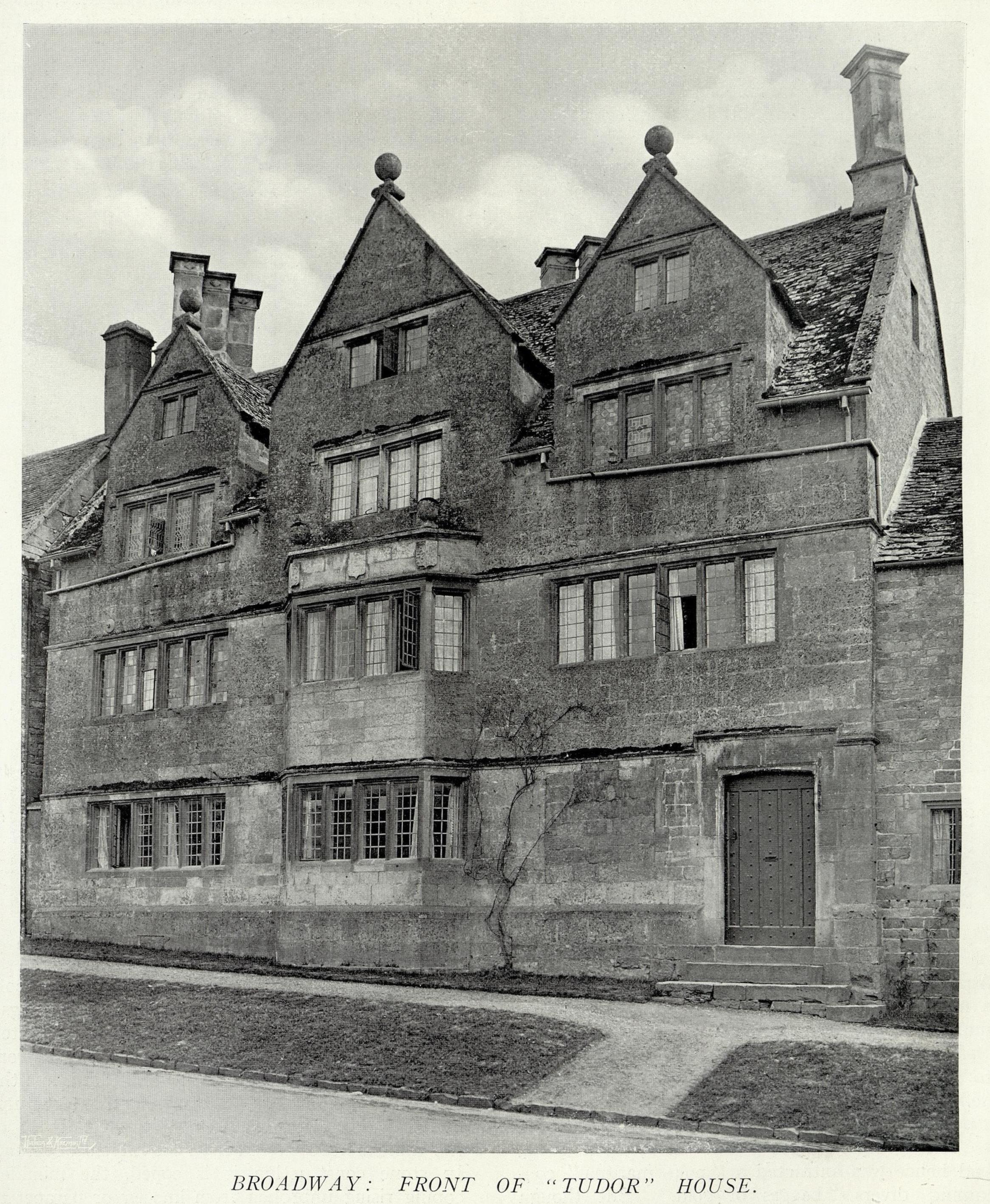

Kneelers and apex are frequently embellished with finials, at first somewhat Gothic in feeling, as at Sandford Orcas (page xli.) and at Parnham (page 9). Still more are they so in East Anglian brick houses in association with crow-stepped gables, as at Barningham (page xxxi.). The tendency, however, was towards some variety of the classic obelisk, ball or acorn, as at Chantmarle (page xii.), Tudor House (below) and Studley Priory (page 25). The gable was freely used, not merely at the ends of a long line of roof, but also along its sides, to give ample light to attic rooms, as at Biddestone (page xxix.). Thus its full value as an incident in the general composition was appreciated, and ambitious designers seized upon the Low Country fashion of breaking its outline by curves, angles, scrolls and additional finials, as at Trerice (page 129) and Kirby (page 69). The latter is very typical of Thorpe and his school, who, besides the elaborated gable, also used in brick houses the cupolaed tower to give variety to the sky-line, as at Madingley (page 59) and Cobham (page 157). This was of still greater value when, towards the end of the period, a flat roof was not infrequently adopted, and thus Doddington (page 391) and Charlton (page 393) look much less gaunt and four-square than Quenby (page 372) and Wootton (page 350). There not only the cupolaed towers are absent, but the chimneys are ineffective, for they do not rise high in well-grouped shafts as in the two first-mentioned houses.

BIBURY COURT: SOUTH FRONT.

BARNINGHAM HALL: THE WEST FRONT.

The English builder of the Early Renaissance period still insisted on the chimney as a prominent factor in design. Such recognition that it was a most necessary adjunct to every habitation in Northern latitudes, and should, therefore, be given an aesthetic consideration conformable to its material importance, continued where and when the native spirit prevailed. In great houses where a designer who knew and followed his Italian authorities was given a free hand, it gradually assumed diminished proportions and eventually became a thing to be hidden or disguised. But even beyond the Early Renaissance period it asserted itself in small manor house and cottage, while well into the seventeenth century it was habitually treated with respect even where stateliness was aimed at, as we have just seen at Doddington and Charlton. It is, however, in smaller and simpler buildings that it plays the most important part, and such houses as Biddestone (page xxix.) and Owlpen (page 257), Batemans (page 285) and Derwent Hall (page 272) depend largely upon it for their exterior charm.

It is, however, neither the gable nor the chimney, but the particular form of the window that is so marked during this period as to make it the most typical feature. It has departed from Gothic tradition by a loss of arched head and tracery, and by a gain in size and frequency. But it continues to have closely-set structural mullions and transoms, whereas the window of the Later Renaissance is a wide, keystoned aperture tilled in with a light wood frame unnecessary to the stability of the building.

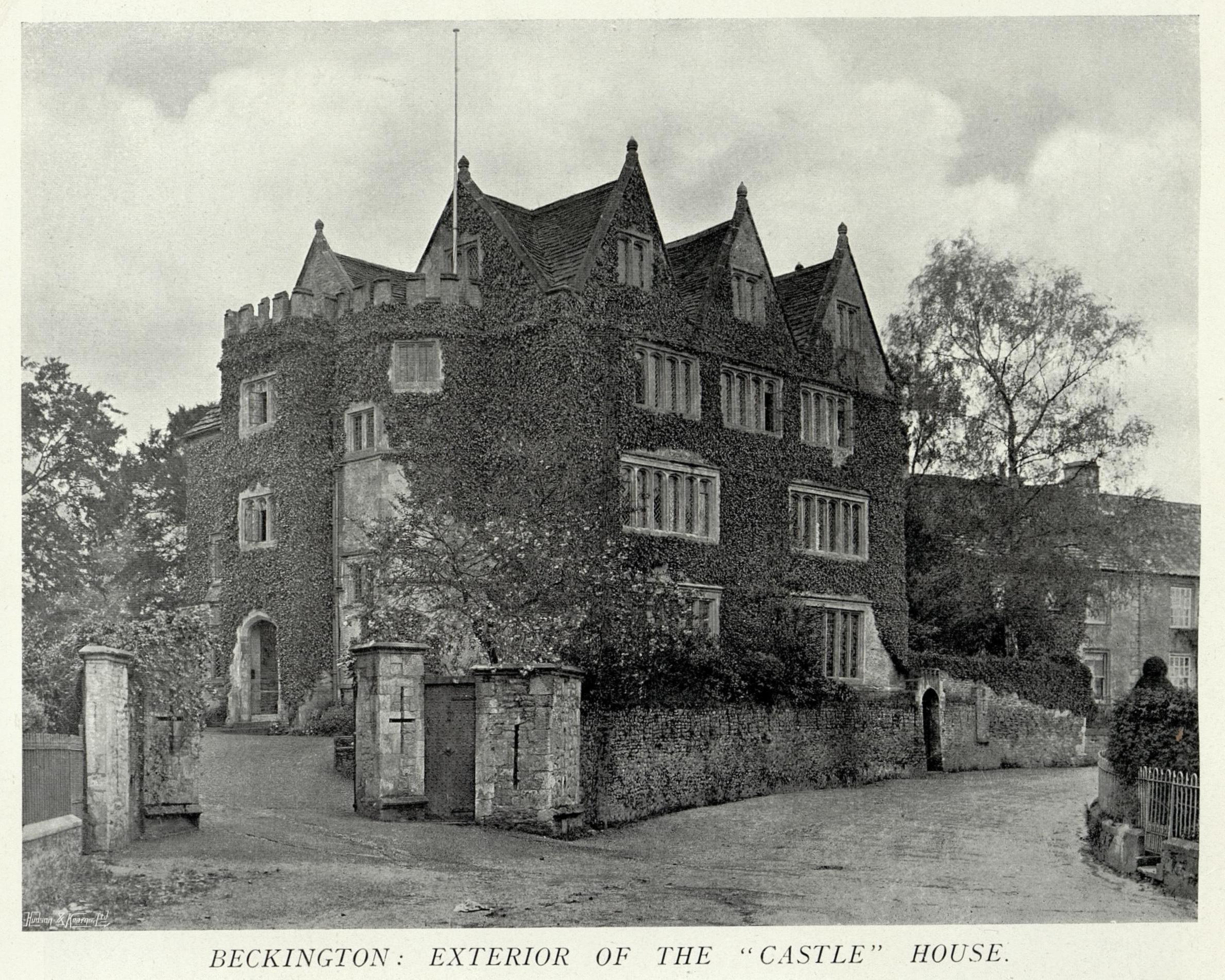

BECKINGTON: EXTERIOR OF THE “CASTLE“ HOUSE.

We find over the Chavenage porch (page 3) a survival of the full arched form. That is unusual, but it was quite customary in Elizabeth’s earlier days to continue the depressed arch for the individual lights that obtained in Henry VIII.’s day when Parnham (page 9) was built, and it is therefore quite likely that the great hall windows at Chavenage date from the year carved on the porch, namely, 1576. It will be seen, however, that the form varies from that at Parnham, in that the arch has very nearly or entirely lost its top angle and gives the impression of being an unbroken curve. So it is at Studley Priory (page 25) and at the Beckington “Castle” House (on this page), and such it continued to be occasionally used even in James I.’s reign when Sir John Strode built Chantmarle (page xii.) before he inherited Parnham, as related on page 16. The square head is, however, the typical form throughout the period. At first we are apt to find the mullioning chamfered or even incurved, as it had been in the fifteenth century, but gradually the ovolo form asserted itself, and little else is found in the later days of Elizabeth and throughout James’ reign except when some special attempt at original treatment was made, as at Brereton (page 205) and still more at Cothelstone (page 311).

SANDFORD ORCAS: THE GATEHOUSE.

That our mediæval ancestors used comparatively small and few windows, not because they liked them so, but because there was danger in large ones and either expense in glazing them or discomfort in leaving them unglazed, is made quite clear when we see how the first generation that enjoyed comparative safety and a sufficiency of glass multiplied and enlarged its windows until Hardwick Hall could be described as “more glass than wall.” Caverswall (page 329) and Wootton (page 349) are in that manner, but earlier houses adopted the fashion, as we note at Kirby, while even in remeto Cornwall a modest manor house, such as Trerice, would have a hall window of eight doubly-transomed lights (page 130). The width of such lights, though greater than in Henry VII.’s days, was very little increased after the death of Henry VIII. There is, for instance, little difference in this respect between those at Chavenage and those at Charlton—the first and last places included in this volume. That was because the mullion was an integral and necessary portion of the structure, built in with the walling at its side and supporting that above it. Therefore increase in the size and number of the windows meant a maintenance of the number and solidity of both mullions and transoms. The Early Renaissance fenestration, when it reaches the development we find at Howsham (frontispiece), almost assimilates itself to the contemporary wainscoting formed of small panels set in proportionate stiles, only in the window the panel is a leaded light and the stile a transom or mullion.

COLD ASHTON MANOR: GENERAL VIEW.

COLD ASHTON MANOR: THE GATEWAY.

The added sense of security which enlarged the windows had a marked effect upon the character and disposition of the structures that adjoined the dwelling proper and formed part of the group of buildings. The mediæval country house generally had a quadrangle of offices in front of the inhabited portion, even though that portion was itself quadrangular, as was usual in a large place. It will be seen on page 358 that in the fourteenth century the Fitzherbert who was the ancestor of the present owner of Tissington rebuilt Norburv with “an outer court of farmery and office buildings and an inner court on to which the new house opened.” No doubt the old house at Charlton which Adam Newton pulled down in James I.’s time was on the same plan, for the lease granted under Henry VIII. and alluded to on page 394 speaks of “buildings within the two inner courts of the manor.” The Renaissance householder did not need such a protection, and asked for a tidier and more dignified approach. The farmery and office quadrangle was therefore placed on the side of the house on to which the kitchen department looked, and there we find it at Chavenage, Quenby, Charlton and many another place included in this volume. But a habit dies hard, and that which dictated an enclosed square before the porch or front door of a house continued in England even beyond the Early Renaissance period. It ceased, however, to be an irregular and untidy yard surrounded by buildings. It took the form of a balanced and well-kept forecourt enclosed by walls of no great height, and sometimes even with open balustrading. Yet buildings were not necessarily entirely abolished. They sometimes formed architectural features at the outer corners, of plain, useful type as at Wootton (page 350) and Water Eaton (page 230), or sumptuously wrought as in the well-known instance of Montacute. Sometimes, too, the idea of a gatehouse was retained, as at Doddington (page 392), where it would conveniently lodge a porter but was not calculated to repel a hostile assault. If there was no gatehouse, the entrance must none the less be made a marked and architectural feature. The archway of the gatehouse was therefore frequently retained and was given some of the newly adopted classic details for its ornamentation. Even the country squire dwelling simply in his small manor house would permit himself such an amenity, as at Cold Ashton, situate on the hills above Bath, and illustrated on this page and the next. There the archway was designed by a man who had studied his John Shute or some other classic authority. The round arch, the rustication and the restraint of pilasters and entablature hint at a fairly direct Italian inspiration, such as we find occasionally in Elizabeth’s early years, but which did not prevail until Inigo Jones’ influence began to be felt in the second half of James I.’s reign, and produced such an archway as that at Charlton (page 399). It offers a decided contrast to the example (below) at Iron Acton in Gloucestershire, probably erected in anticipation of Oueen Elizabeth’s visit there in 1575. The flat-pointed arch with its spandrels and returned drip moulding indicate a traditional designer who, nevertheless, is sufficiently advanced to surmount his design with a classic pediment.

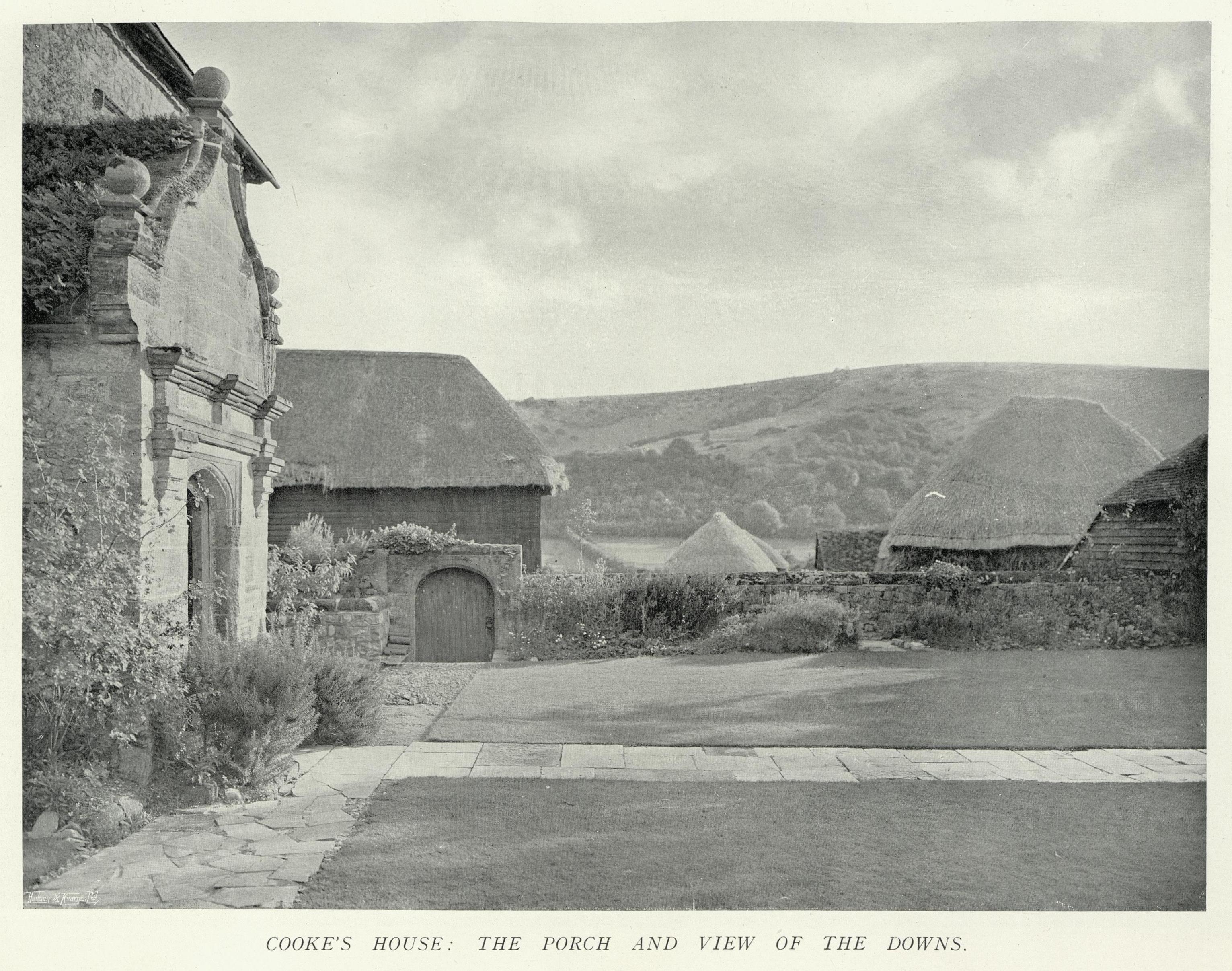

COOKE’S HOUSE: THE WAY UP TO THE GATEWAY.

COOKE’S HOUSE: THE PORCH AND VIEW OF THE DOWNS.

IRON ACTON: GATEWAY TO THE COURT HOUSE.

On a still humbler scale than Cold Ashton is the delightful little scheme of entry at Cooke s House (page xxxvi.)—a place “of no importance” in Sussex. It stands on a south slope with a fine view of the Downs, and the ground which forms its garden lies some feet above the road. A little higher up the hill, therefore, a causeway leaves the road and carries a path of easy gradient up to the level of the garden or forecourt entrance—a little arched doorway of considerable presence, being made of ashlar and having a pediment and ball-topped finials above its arch. The boundary wall to the north is kept high, so that no one walking up the path and knocking at the door can see over. But south of the doorway the wall is lower, for the rapidly-descending road even thus ensures privacy to those within, and yet gives them a view on to the road and over the prospect beyond. A broad flagged way bisecting the trim grass plat leads from the entrance to the porch (page xxxvii.), which forms a corresponding architectural feature, and the only one the little house can boast of.

KIRBY: THE SIDE ENTRANCES TO THE FORECOURT.

That the forecourt was the successor of the old outer farmery court is made clearer when we remember that, where, owing to the requirements of a great man, the quadrangular plan was retained, there was a forecourt beyond it. At Kirby this was added to Sir Humphrey Stafford’s unfinished house by Sir Christopher Hatton, who is also responsible for the similar one at Holdenby, where the entrance arches are dated 1685. His forecourts were so large that he was not content to enter them from the side facing the house only, but also through the flanking walls. The latter entrances at both houses took the form of high, round-headed arches between two masses of masonry set with niches.

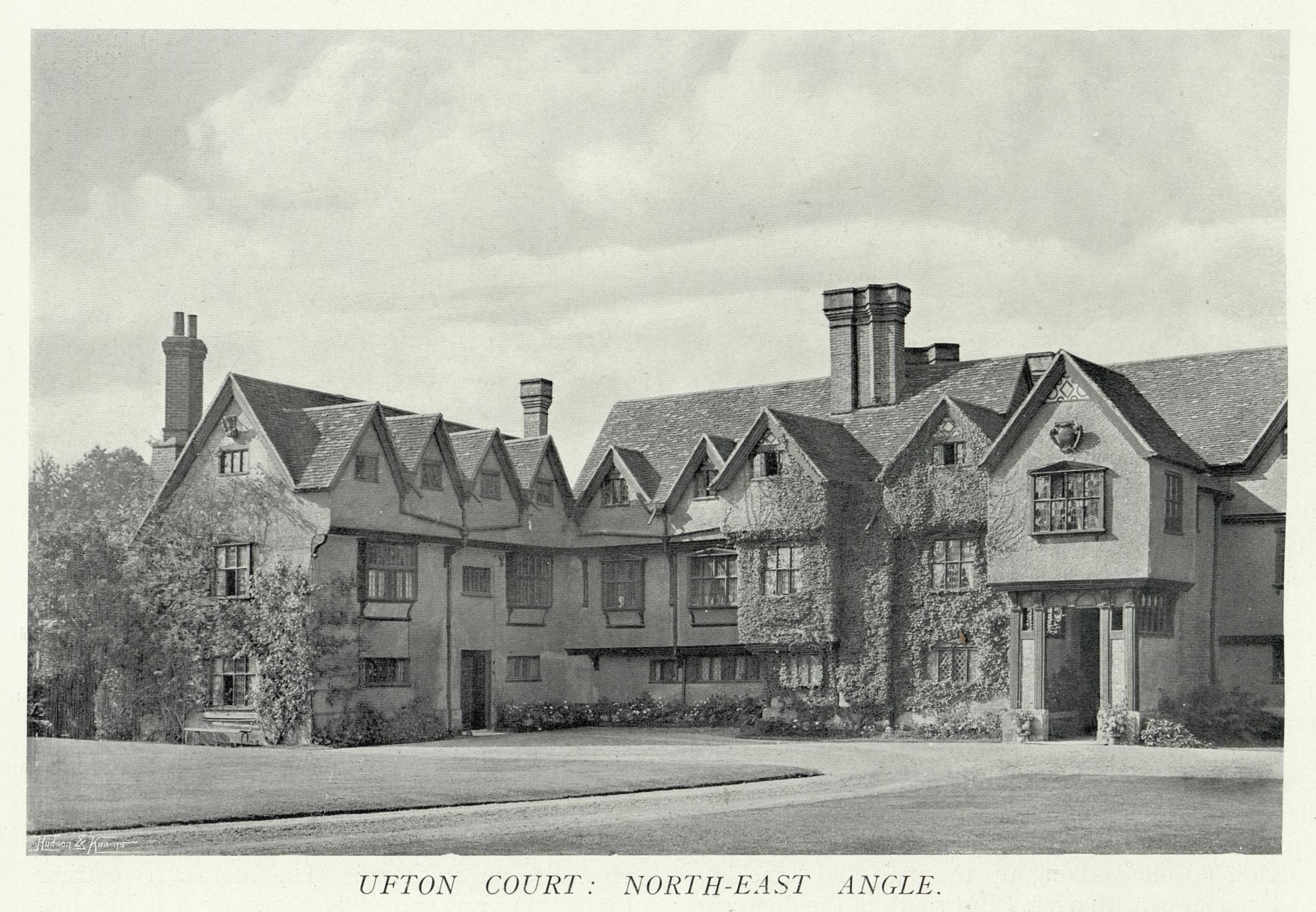

At Holdenby the superstructures, which can hardly be called pediments, but resemble the achievements of strapwork and other Flemish motifs that often topped great chimney-pieces, remain, but over the east and west archways of Kirby they are gone, as the illustration on this page shows. The northern entrance (page 71) was no doubt remodelled by Inigo Jones when he redid the north front of the house. Both the broken pediment and the niche were favourites in the Late Renaissance period, but they were also used, especially the latter, under Fdizabeth. Sir Christopher Hatton’s gateways, that depend for effect so largely upon the niches, may be in this respect compared with Sir John Stawel’s Cothelstone gatehouse (page 310), which, however, is a little structure rather apart and distinct in design. Much more normal in design are the gatehouses at Sandford Orcas (page xxxiii.) and at Borwick (page 163), but in position they are singular in not facing the porch in the manner that symmetry was demanding. As soon as the gates were opened it was the porch that the visitor was to see before him. It was therefore the leading feature of the most important elevation, and it became customary to heap upon it the new ornament derived circuitously from classic sources and adapted—often with more zeal than learning—by the English craftsman. But the whole idea, of the porch and, for long, its general form and main lines were a legacy from Gothic times. The porches at Ufton on this page and at Sandford Orcas on the next, one in timber and the other in stone, have a general resemblance to those of fifteenth century houses and churches—an archway into a lobby, over which is a room with mullioned window under a gable. In the stone example the octagon corner shafts and the finials to the gable copings are mediæval forms with only small Renaissance influence in their details.

UFTON COURT: NORTH-EAST ANGLE.

So also in brick at Barningham (page xxxi.), an East Anglian house reminding us of Breccles and of Seckford, but rising to a height of four storeys, and having great dignity. The blending of Gothic and classic is interesting. Associated with octagon shafts, domical finials, crow-stepped gables and corbelled cornice are low-spreading pediments to the windows and to the doorway (page xliv.). Here the round-headed arch, the acanthus-leaved consoles and the flat strapwork ornamentation of the entablature frieze speak of the new influence, which, however, is most fully present in the temple-front framing of the heraldic panel. The same scheme occurs over the Bibury doorway (page xlv.), where the rusticated arch and flanking pilasters show a more thorough invasion of the Renaissance which imposed the classic orders, with more or less completeness, upon almost every porch of the period. It might merely have a pair of very flat pilasters supporting a simple entablature, as at Ablmgton (page xlii.), or it might reach tower height and have four sets of superimposed twin columns, as at Stony hurst (page 172), where all the four orders display themselves, beginning at the base with the solid Doric and ending at the top with the much-detailed “Composita or Italica the Tryumphant pillor, devised by the Romanes,” as Shute describes it.

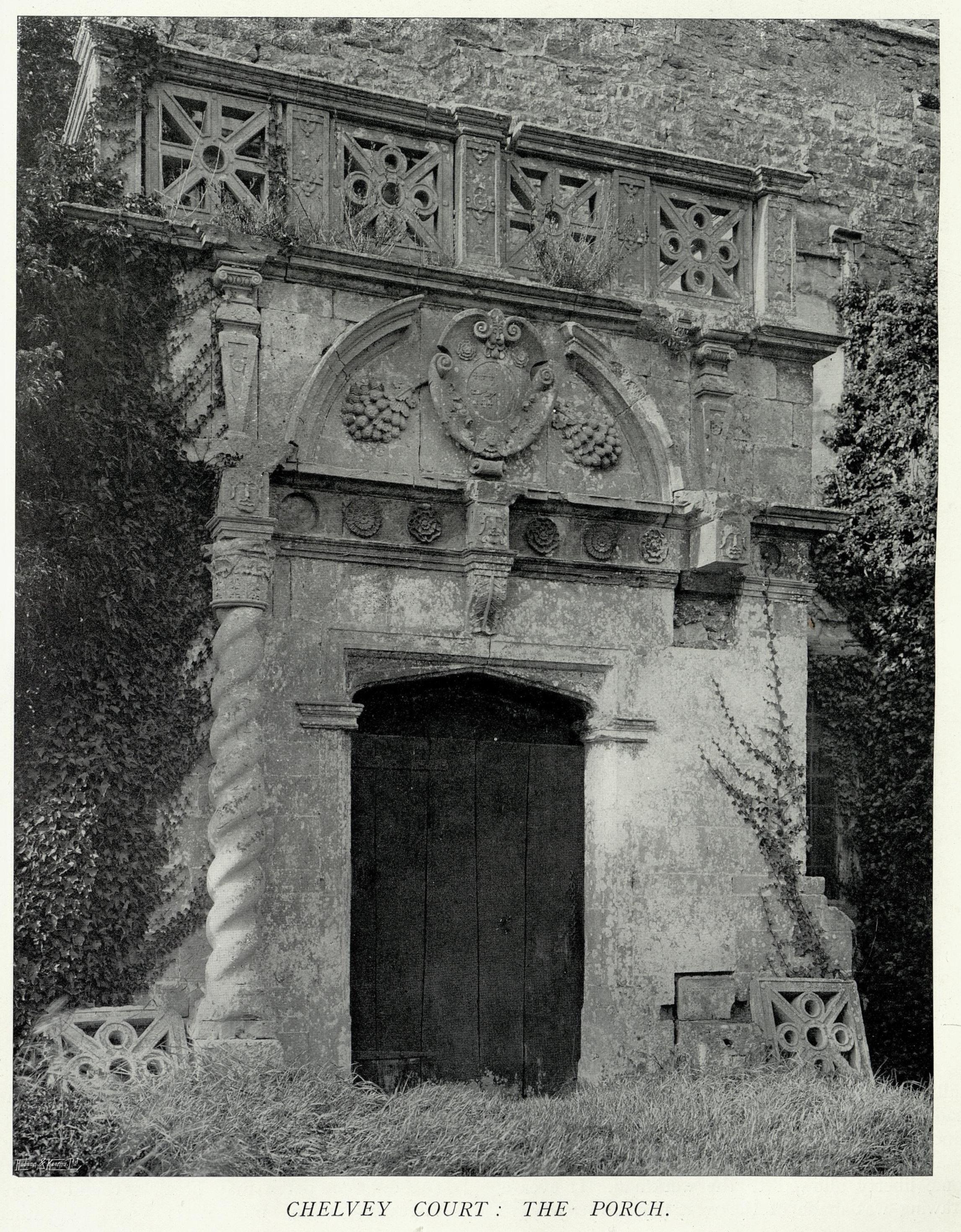

A single-storeyed porch of much charm, though in sad decay, is to be found at Chelvey (page xlvi.). It is rather a late example, having the twisted or “barley sugar” columns that were so popular an introduction from Italy in James I.’s later years, as we see them in wood at Gwydir (page 116). But the Chelvey porch is by a local designer, who still forms his doorway with a touch of Gothic, and does not quite know how to set his broken pediment on to his entablature.

SANDFORD ORCAS: THE PORCH.

At Flow sham (frontispiece) there is the same idea as at Stony hurst, but limited to two storeys, the Corinthian order being set upon the Ionic in due gradation. The proportions are good, following, no doubt, very nearly the exact dimensions laid down by Shute, but the designer has, as was most often the case, failed to grasp the structural purpose of the column, and uses his elaborate superposed arrangement merely as a stand for a pair of little ornaments in the Flemish strapwork manner.

This Flemish influence increased as Elizabeth’s reign went on, and in 1594 de Witte used, on a rather more elaborate scale, the same sort of terminals to his orders on the south porch of Cobham (page 160).

ABLINGTON MANOR: THE ENTRANCE FRONT.

The poor fight made by the Italians and the easy triumph of the Flemings in the realm of Elizabethan architecture is curious, but by no means difficult to understand. For long the trade relations between England and the Low Countries had been exceedingly close. To these were added political and religious ties, especially with those Northern provinces which, throwing off the yoke of Spain and the tenets of Rome, ultimately became the Dutch Republic. To help them in their struggle Elizabeth sent an armed force under her favourite Leicester, and on their soil Sir Philip Sidney died. From the Southern provinces which adhered to Spain came to our shores many a capable craftsman who hated Rome more than he loved his home. Such causes influenced English taste, but besides these, which were in a measure accidental, there was the natural sympathy of two peoples of blood kinship, close neighbourhood and similar climatic needs. Adapting to their own use and taste the Renaissance ideas first developed in Italy, the Dutch and Flemings retained much that was old and local, such as high-pitched roofs, to which also the English builder was wedded. He therefore turned to them for tuition and support rather than to a school with forms and theories alien to his traditional ideas and his native needs. In the decorative sphere there was a similar bond. The Dutch, while basing their efforts on classic foundations, adopted a florid style with exuberant forms of mixed origin and free treatment. Their designers went into print, Hans de Vries—called the king of architects by his own countrymen—bringing out several illustrated books during the second half of the sixteenth century. They were seized upon by English craftsmen, who found them an apt starting-point from which to develop their own particular bent and limited powers. They were thus able to produce a rich and pleasing effect without long training in classic rules, careful study of anatomy and other natural forms or painstaking efforts to reach technical excellence.

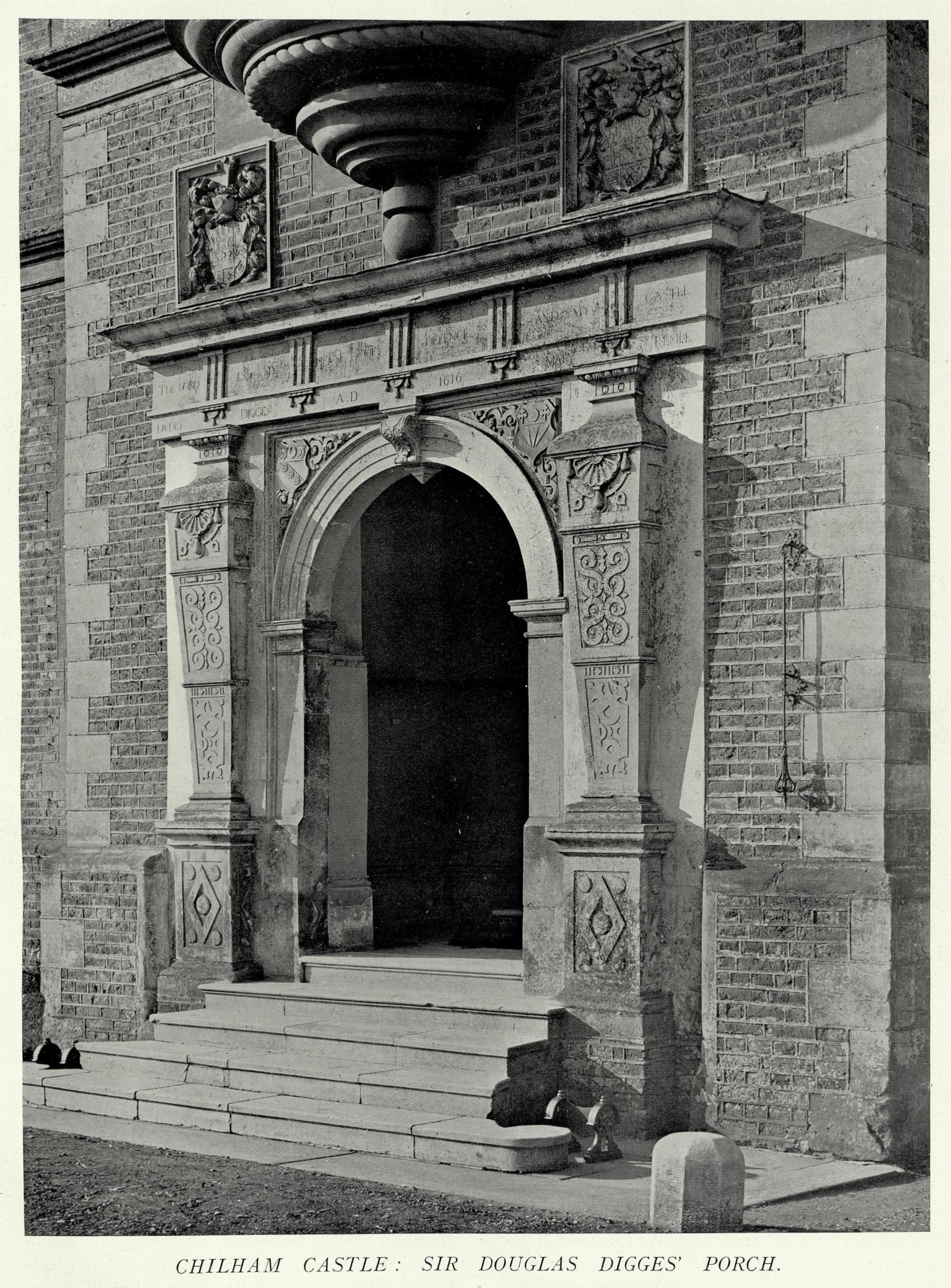

CHILHAM CASTLE: SIR DOUGLAS DIGGES’ PORCH.

BARNINGHAM HALL: THE PORCH DOOR.