|

|

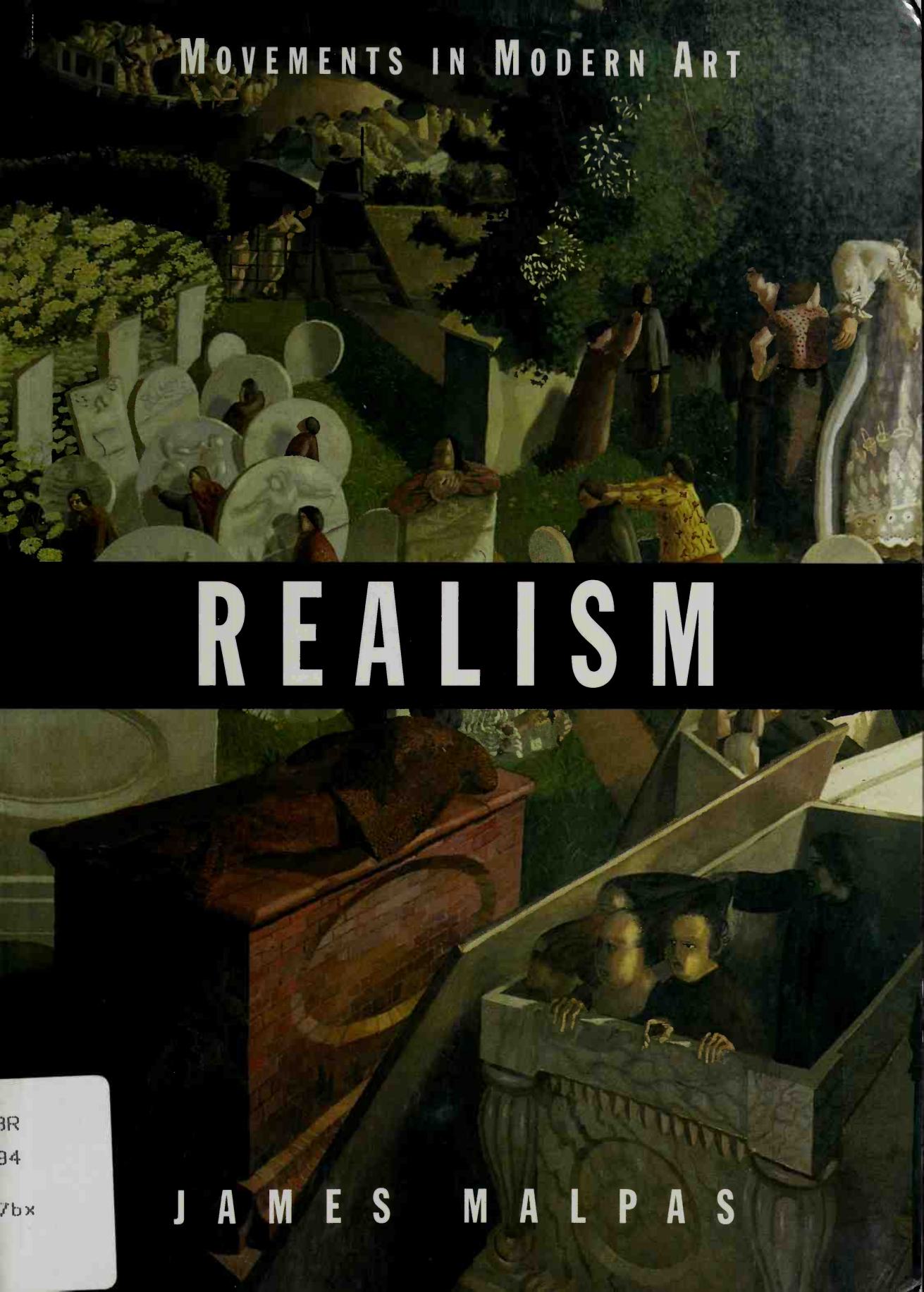

James Malpas. Realism. — London, 1997  Realism / James Malpas. — London : Tate Gallery Publishing Ltd., 1997. — 80 p., ill. — (Movements in Modern Art). — ISBN 0-521-62757-5Movements in Modern Art.

This series introduces the most important movements in late nineteenth- and twentieth-century art. Each book is illustrated chiefly in colour with works from the Tate Gallery and other major collections around the world.

Realist art of the twentieth century is striking for its diversity. It has no shared style or manifesto of intention. Yet a common thread in realist art is a commitment to the modern world and to things as they are. This book examines realism in Europe and America, beginning with its roots in the aims of Gustave Courbet in nineteenth-century France.

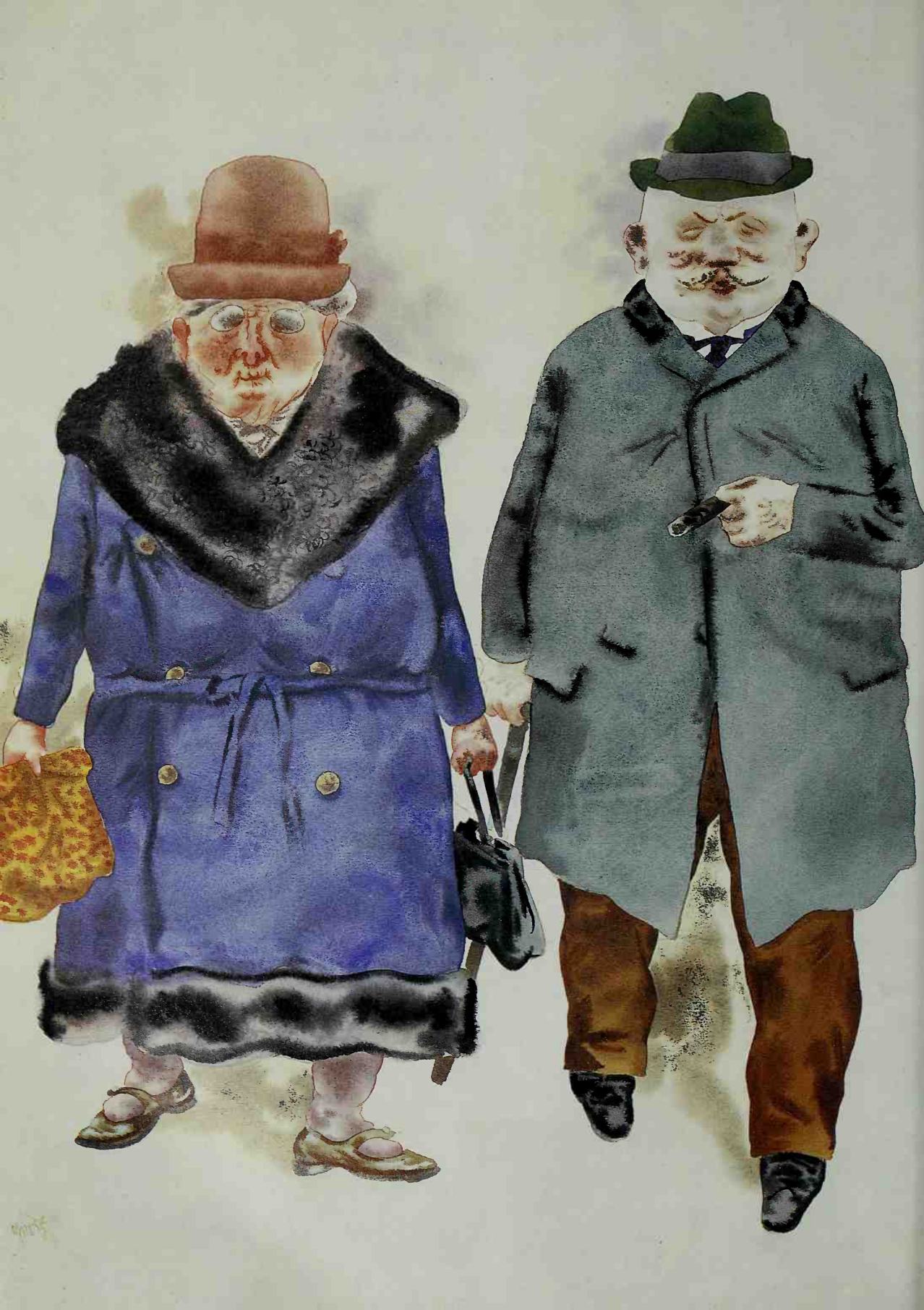

The realist outlook is exemplified in the work of Georg Grosz in his observations of urban life in Weimar Germany or, in America, in the high focus paintings of Edward Hopper and Grant Wood. The author also examines the so-called ‘socialist realism’ of Stalin’s Soviet Union and the condemnation in Germany of artists not conforming to Nazi academic-realist demands. He describes French and Italian painting between the wars and the political intentions of Mexican muralist Diego Rivera. British realists, amongst them Stanley Spencer, Lucian Freud and David Hockney, are discussed in detail, as are the Pop artists Richard Hamilton and Andy Warhol.

Introduction

Realism is in danger of becoming, to use Henry James’s phrase, a 'baggy monster', spilling out into virtually every art movement and group since it came of age in the declarations and work of the Realist painter Gustave Courbet in France from the 1840s, and in the contemporaneous commitment of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood in England to a return to nature. After all, no artist refers to their work as unreal, or anti-real. Indeed, even the most extreme abstract art has consistently been claimed by its practitioners as a form of realism: in 1920 the Russian Constructivist, Naum Gabo, published his Realistic Manifesto; in the early 1960s the New Realist group in France comfortably accommodated Yves Klein, known for his monochrome canvases. These artists stood the term realism on its head to make it mean an art which opposed the imitation of reality in order to establish itself as a new reality in its own right. This definition is a crucial cutting-off point for this book; for a work of art to be included here it has to have some perceptible root in the considerations, both of subject matter and technique, of the nineteenth-century exponents of Realism.

There are also areas of painting where realist subject matter is married to an Expressionist use of paint, loaded with emotional charge, as in much of the Kitchen Sink school in the Britain in the 1950s (John Bratby for example) and in the very painterly work of the British artists Frank Auerbach and Leon Kossoff, where realism seems to be abandoned rather than enhanced. (By contrast, Lucian Freud never goes into the same arena of gestural commitment in his brushwork, maintaining something of a Ruskinian humility before the subject.) If one included such expressionistic gestural painters, one would also need to refer to Meidner, Soutine and de Kooning's majestic Women series, as well as earlier German Impressionism as a whole, which would widen the frame of reference so much as to make the term 'realist' almost meaningless in a book of this length.

It is impossible to ignore the relationship of photography to the realist tradition in painting and of course to modern art in general. Photography both provoked painters to become less realistic, to distance themselves from this rival, and gave them the means to become more realistic. In the latter case, their often unacknowledged use of the ‘foe-to-graphic’ art (Edwin Landseer’s pun) shows how sensitive they were to accusations of plagiarism. However, photography, though an eminence grise of realism, needs far more extensive treatment than the scope of this book will allow; and there are many easily available histories of the subject (see Further Reading).

As a quality, realism is positive, denoting toughness, down to earth attitudes to life or death and a practical outlook on the way things should be managed. It also presupposes the need for management of, or at least of some measure of control by man over, the environment or his fellow human beings. The need for realism, in both life and art, may be the result of a sense that fantasy, imagination, speculation have all run away with human attention and that things as they are have been shunted into the area labelled ‘ordinary, everyday, uninteresting’.

In relation to art, realism has the great advantage of ubiquitous subject matter. Anything that actually happens or exists is seen as worthy material. However, it is at the level of interpretation of those events and things that the interesting difficulties in defining realism appear.

In their response to things and events in the world, realists aim at a level of objectivity that ‘romantics’ abhor. Yet what is the nature of this objectivity? That proposed by Courbet in about 1849 is different from that simultaneously embraced by the Pre-Raphaelites, yet both could be accommodated under the realist umbrella.

Paradox underlies the approach of nearly all artists claiming to be ‘realists’ and this applies particularly to those in the twentieth century. Unlike Courbet, these artists do not usually establish a proselytising Realist stance, with defined aims. They are often individuals, defining themselves against the so-called progressive or avant-garde trends of the day, or indeed, simply ignoring them. The concept of an avant-garde, popularised by the critic Julius Meier-Graefe around 1910 to account for the successive waves of isms in European art from the early nineteenth century, is in danger of skewing any assessment of art into the ‘cutting edge’ versus the ‘has-beens’. Certainly, except for brief periods, the realist tendency has been relegated to the also-ran category throughout the twentieth century, by the cognoscenti, the major collectors, and often the avant-garde artists themselves.

Realism in the twentieth century, then, exhibits a protean stylistic and ideological approach. It can range from the passionate and quirky individualism of a Stanley Spencer to, contemporaneously, the most demoralised institutionalism of an ‘apparatchik’ painter like Alexander Gerasimov in the Stalinist USSR, where it appears under the guise of ‘socialist realism’. Any attempt to provide a cogent definition, as one can in the case of a relatively team-based, well-knit ‘ism’ such as Surrealism, will be thwarted at the start. For the most part, realism in the twentieth century is not ‘Realism’, that’s to say, something consciously signed up for, via a manifesto, to show a party allegiance.

From its roots in the nineteenth century, Realism encompasses a bewildering range of styles: we now see Courbet and the Pre-Raphaelites equally as Realist painters, but their stylistic hallmarks and paint-handling are significantly different. And, whereas a Surrealist, having ‘joined up’, made more or less conscious efforts to ensure a correct Surrealist component in his work, no such compunction weighed on so-called ‘realists’, except in totalitarian states. For the realist, the saleability of a work might motivate the artist as much as any ideology. Realism in the twentieth century can thus be seen in terms of highly individual figures appearing almost at random. And yet there were periods when the tide of realism was flowing high, notably after the cataclysm of the 1914—18 Great War (see chapter 2) and to some extent after the Second World War.

Many interesting questions arise when considering realism in later twentieth-century art. How ‘realist’ is Pop Art? On one level its adherence to the trivial, the everyday, the trashy and throw-away is counter to Courbet’s notion of contemporary heroism (let alone Pre-Raphaelite moralising). Yet at the same time this aspect corresponds to the realist idea that art can encompass the most humble and everyday subject matter, and Pop’s heroes were often working class, like Courbet’s.

Contents

Introduction 6

1. The Beginnings of Realism.. 9

2. Realist Painting in England 1900–1940.. 16

3. Realism Between the Wars.. 26

4. European and British Realism after 1945.. 50

5. American Pop Art and Realist Painting since 1955.. 62

6. Superrealism, Photorealism and Realism in the 1980s.. 69

7. American and British Realism Post-Pop.. 72

Conclusion.. 75

Select Bibliography.. 77

Index.. 78

Sample pages

Download link (pdf, yandexdisk; 18,3 MB).

Все авторские права на данный материал сохраняются за правообладателем. Электронная версия публикуется исключительно для использования в информационных, научных, учебных или культурных целях. Любое коммерческое использование запрещено. В случае возникновения вопросов в сфере авторских прав пишите по адресу 42@tehne.com.

5 октября 2020, 1:16

0 комментариев

|

Партнёры

|

Комментарии

Добавить комментарий