|

|

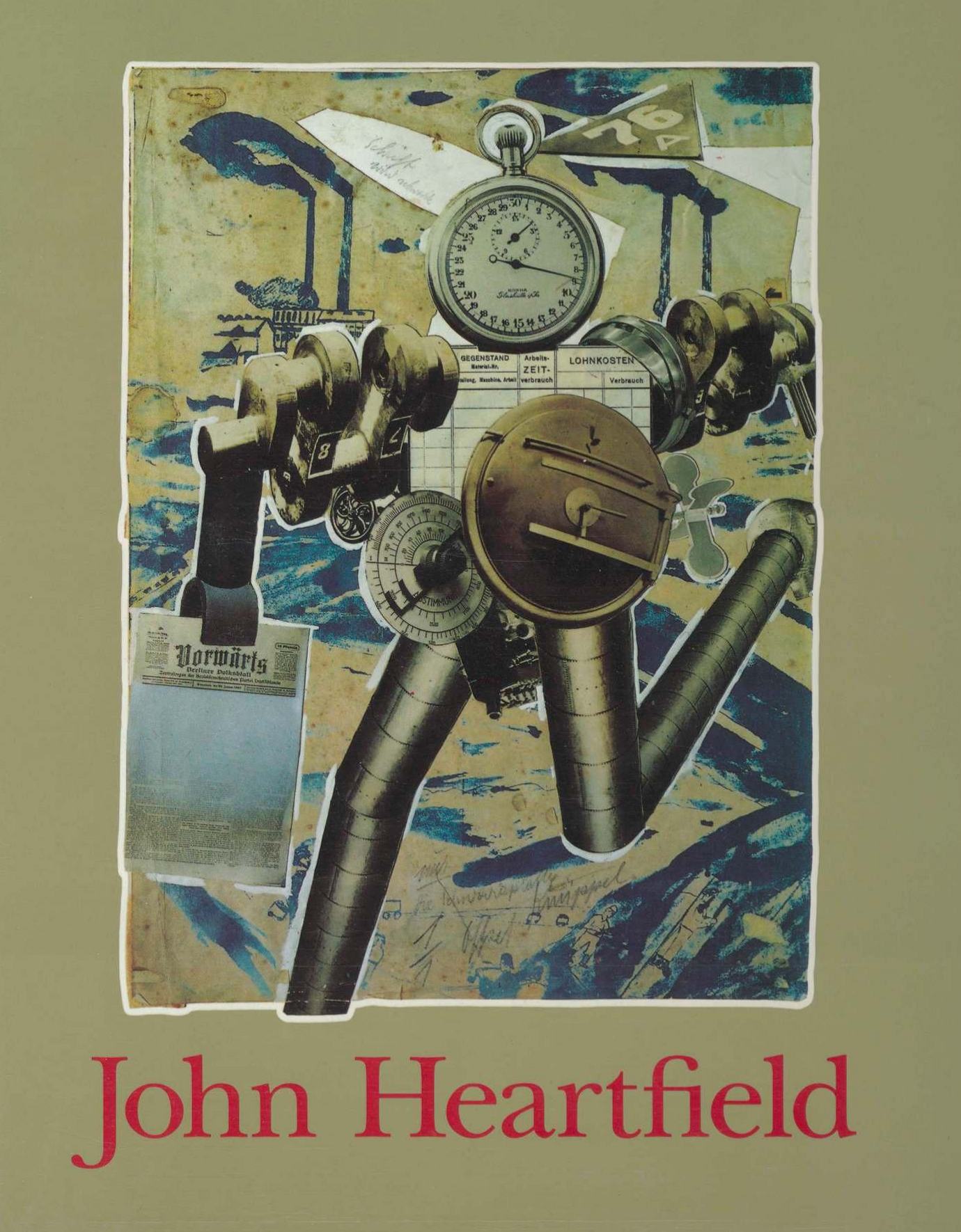

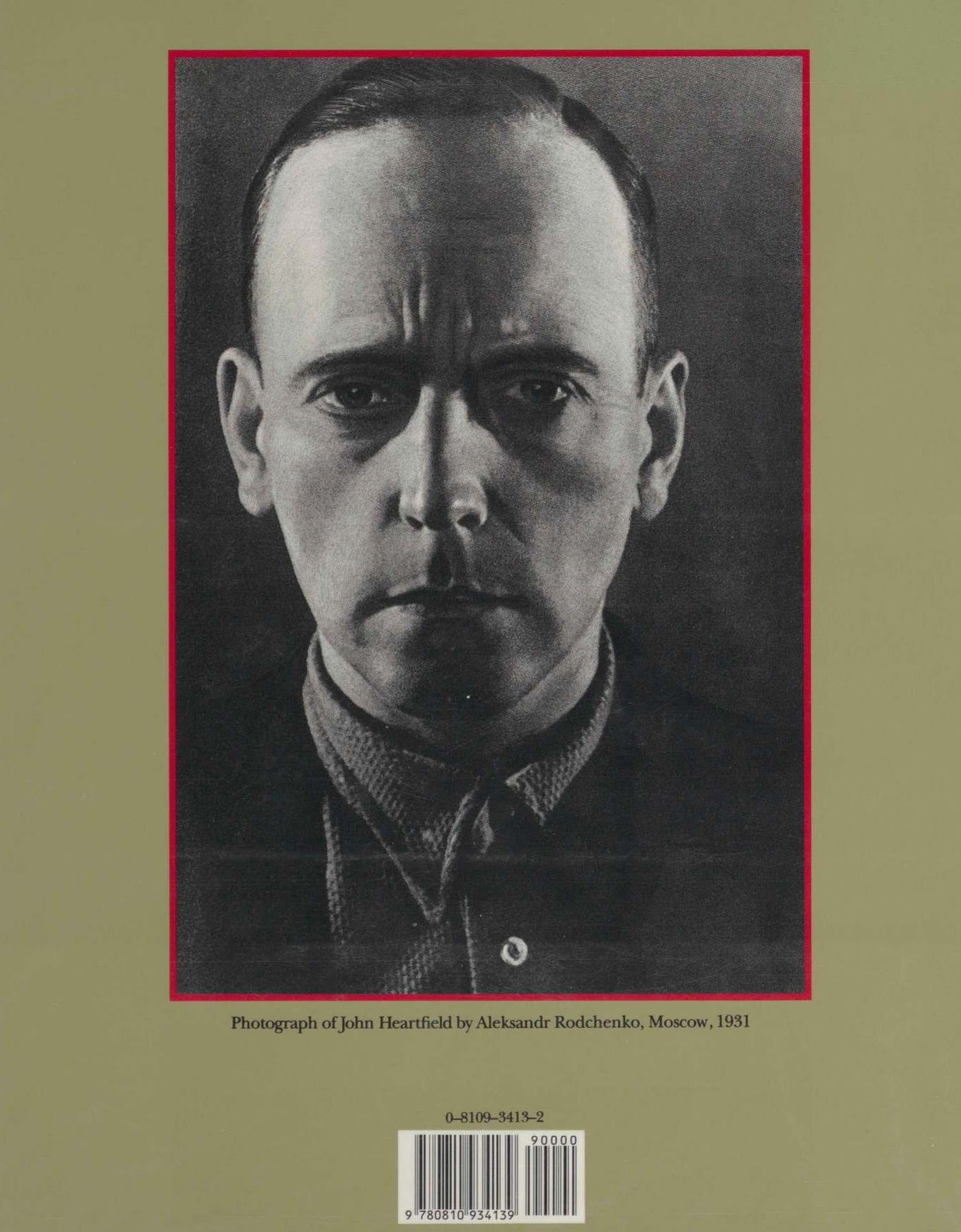

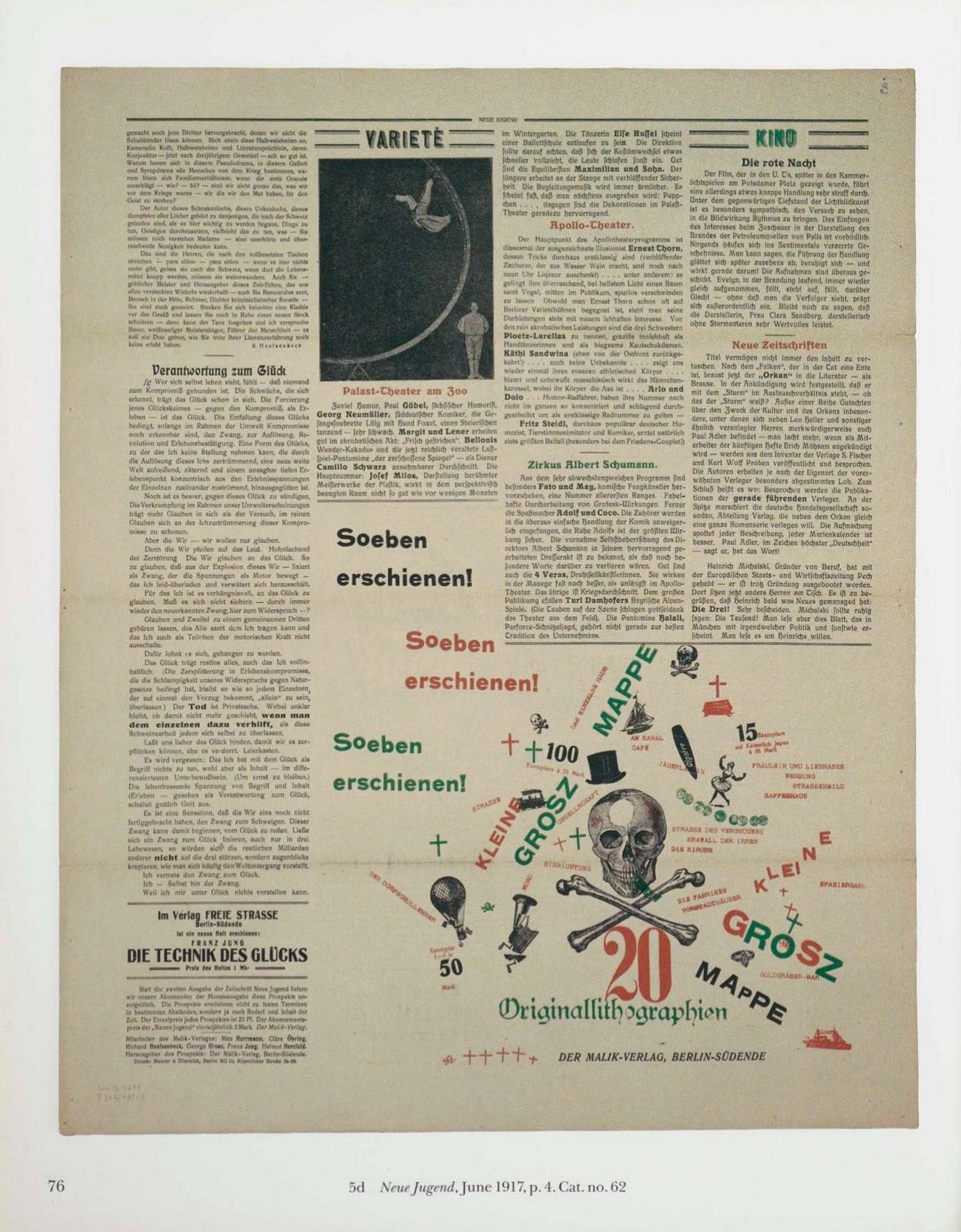

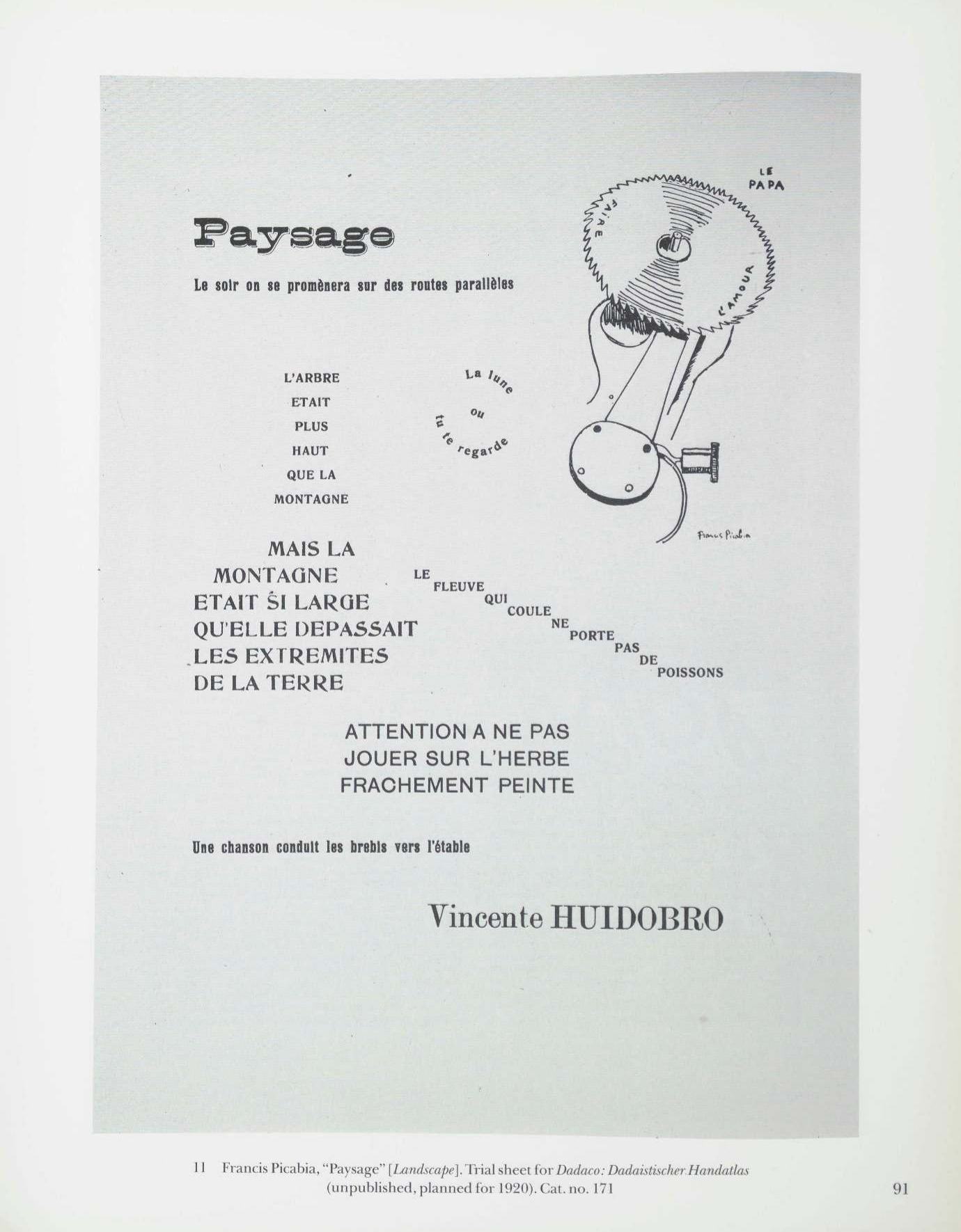

John Heartfield : Catalogue of an exhibition. — New York, 1992John Heartfield : Catalogue of an exhibition / Edited by Peter Pachnicke and Klaus Honnef. — New York : Harry N. Abrams, Inc., Publishers, 1992. — 342 p., ill. — ISBN 0-8109-3413-2

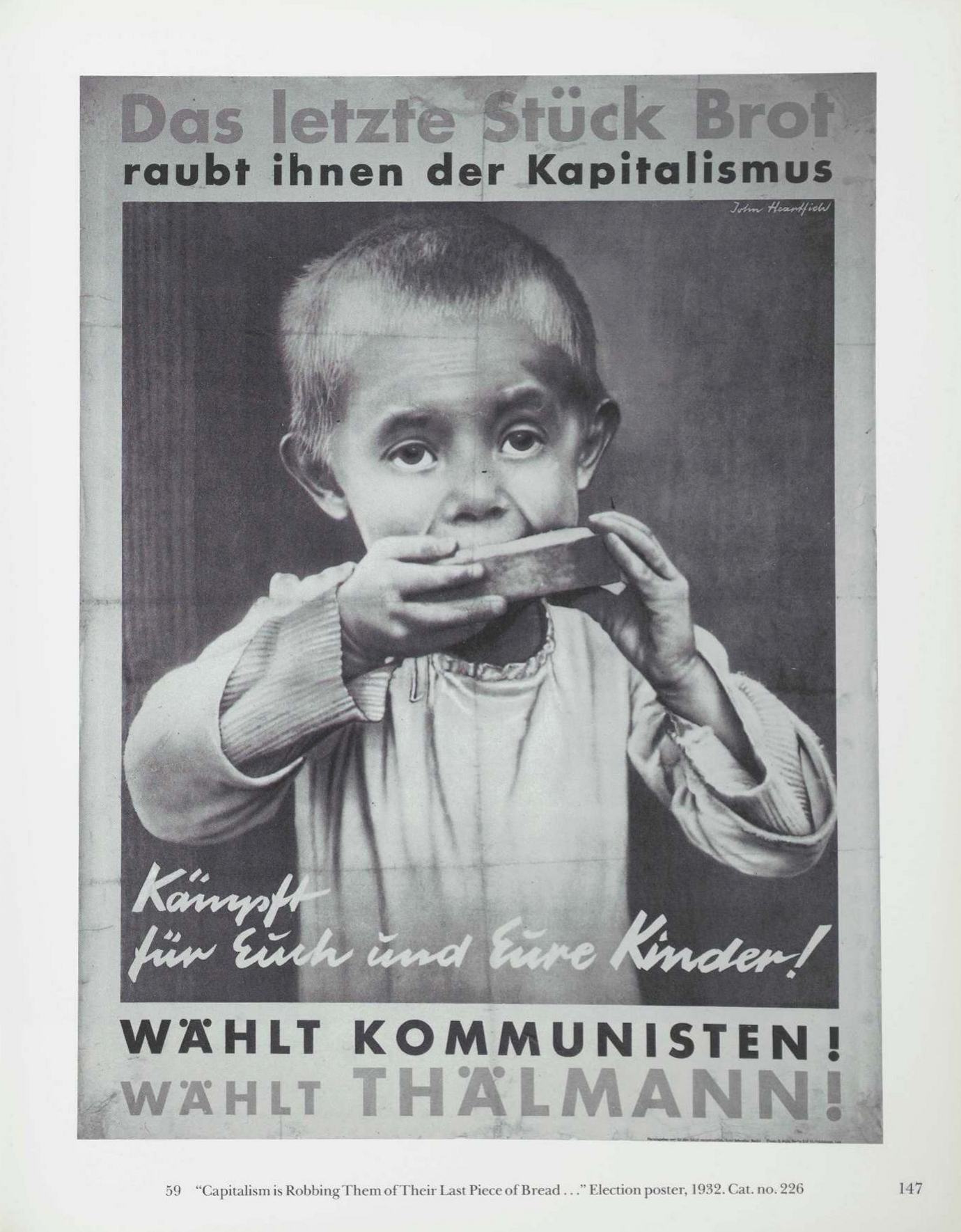

Born Helmut Herzfeld in 1891, John Heartfield anglicized his name as a protest against German nationalism during World War I. In 1929 Heartfield began his long collaboration with AIZ, furnishing full-page photomontages nearly every month. Forced to flee Germany after Hitler came to power, he continued to create work for AIZ while in exile. He spent the war years in England, where he worked as a graphic artist. Heartfield was an active supporter of Communism and in 1950 returned to what was then East Germany. He continued to work there, mostly designing scenery and posters for the Berliner Ensemble and Deutsches Theater. Heartfield died in East Berlin in 1968, leaving an extensive archive, which, upon his widow’s death, was transferred to the Akademie der Künste zu Berlin. Given Heartfield’s leftist political leanings, his work has rarely been shown in the West. His first exhibition in New York was in 1938; the next was in 1991, when pages from the AIZ were shown.

The works in the exhibition were chosen from the 1991 touring retrospective commemorating the centenary of the artist’s birth, organized by the Akademie der Künste zu Berlin, the Landesregierung Nordrhein-Westfalen, Düsseldorf, and the Landschaftsverband Rheinland, Cologne.

John Heartfield

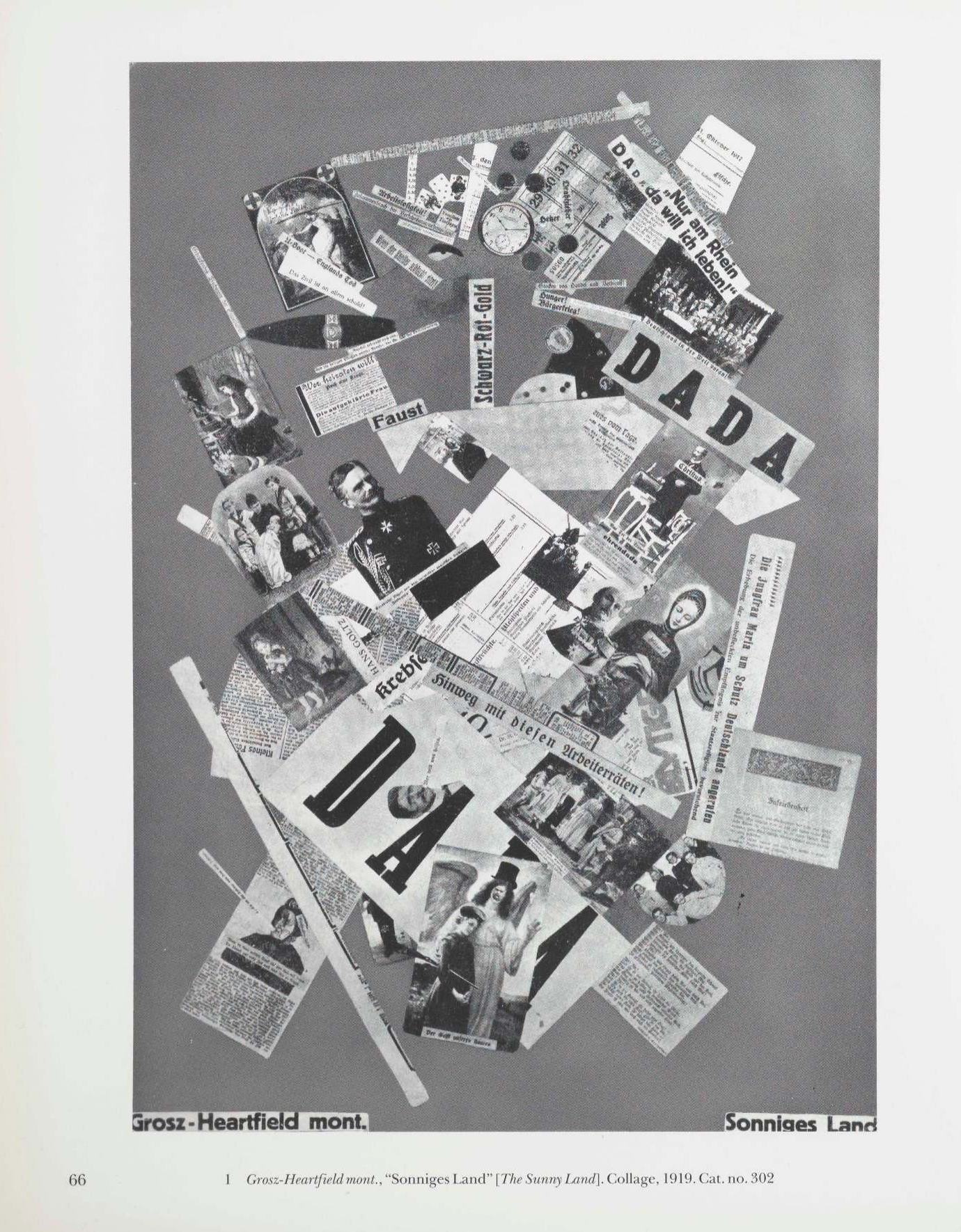

The German artist John Heartfield (Helmut Herzfeld, 1891—1968) is known primarily as one of the inventors of photomontage—pictures made from fragments of photographs and other visual material—and as a member of the Berlin Dada group in 1920. But he soon broke with the Dadaists, since they did not fulfill his radical conception of the artist’s role in society. He shared with the more widely known artist George Grosz a distaste for the materialism, greed, and immorality rampant in Germany in the 1920s, and both artists changed their names at the same time as an anti-German protest. But Heartfield’s aim was to mobilize social energy, to expose with his forceful political art the evils, corruption, dangers, and abuses of power in the Nazi regime.

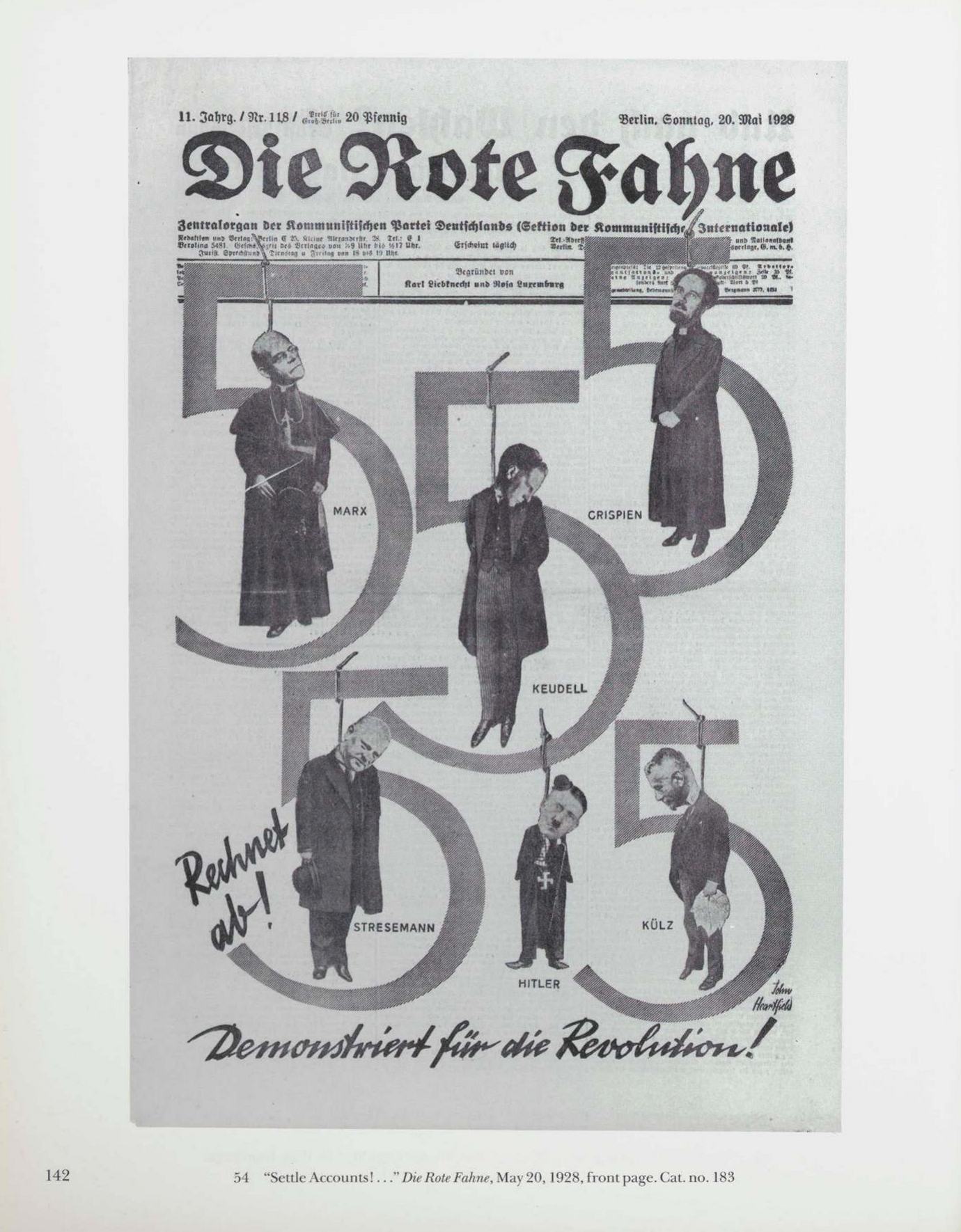

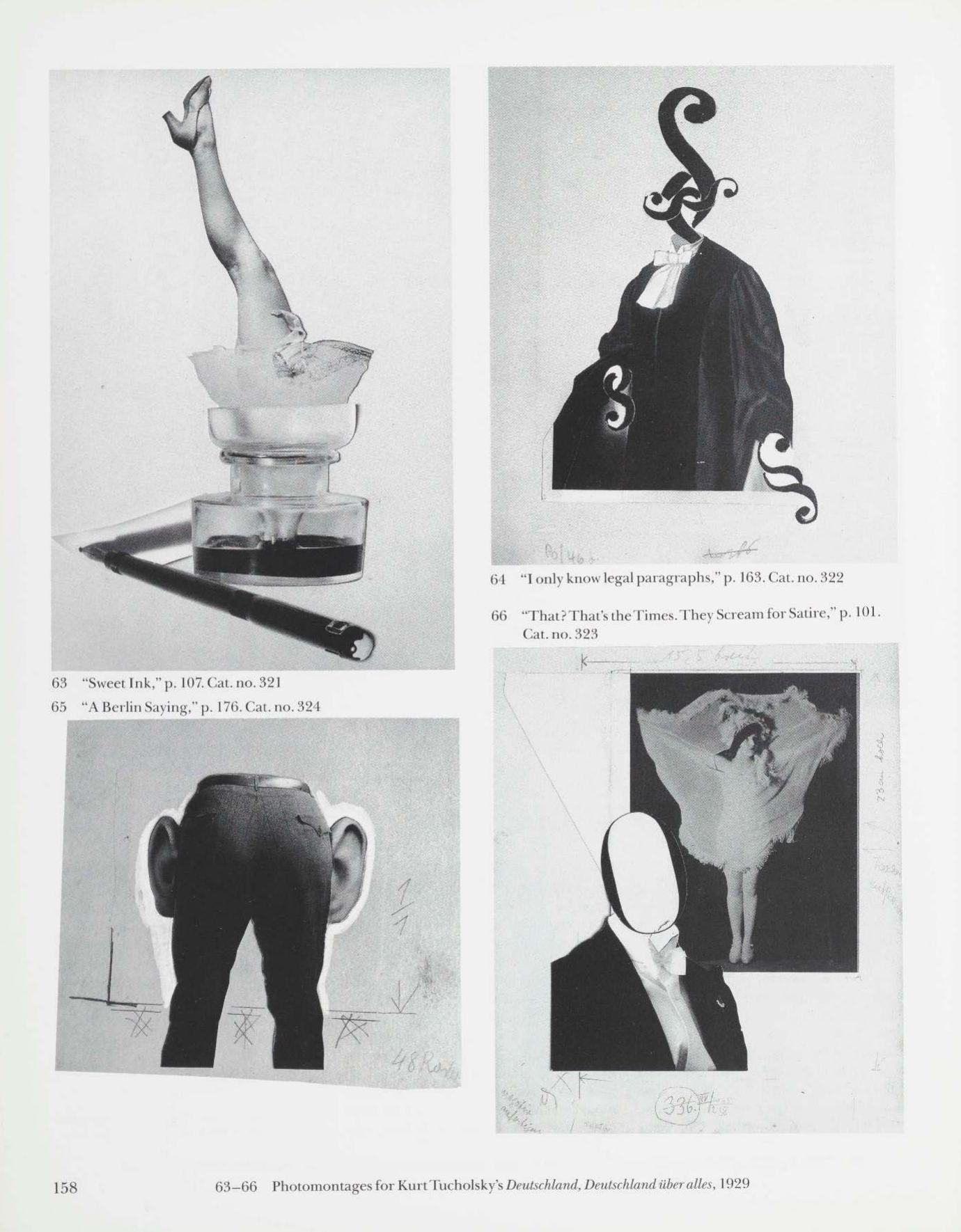

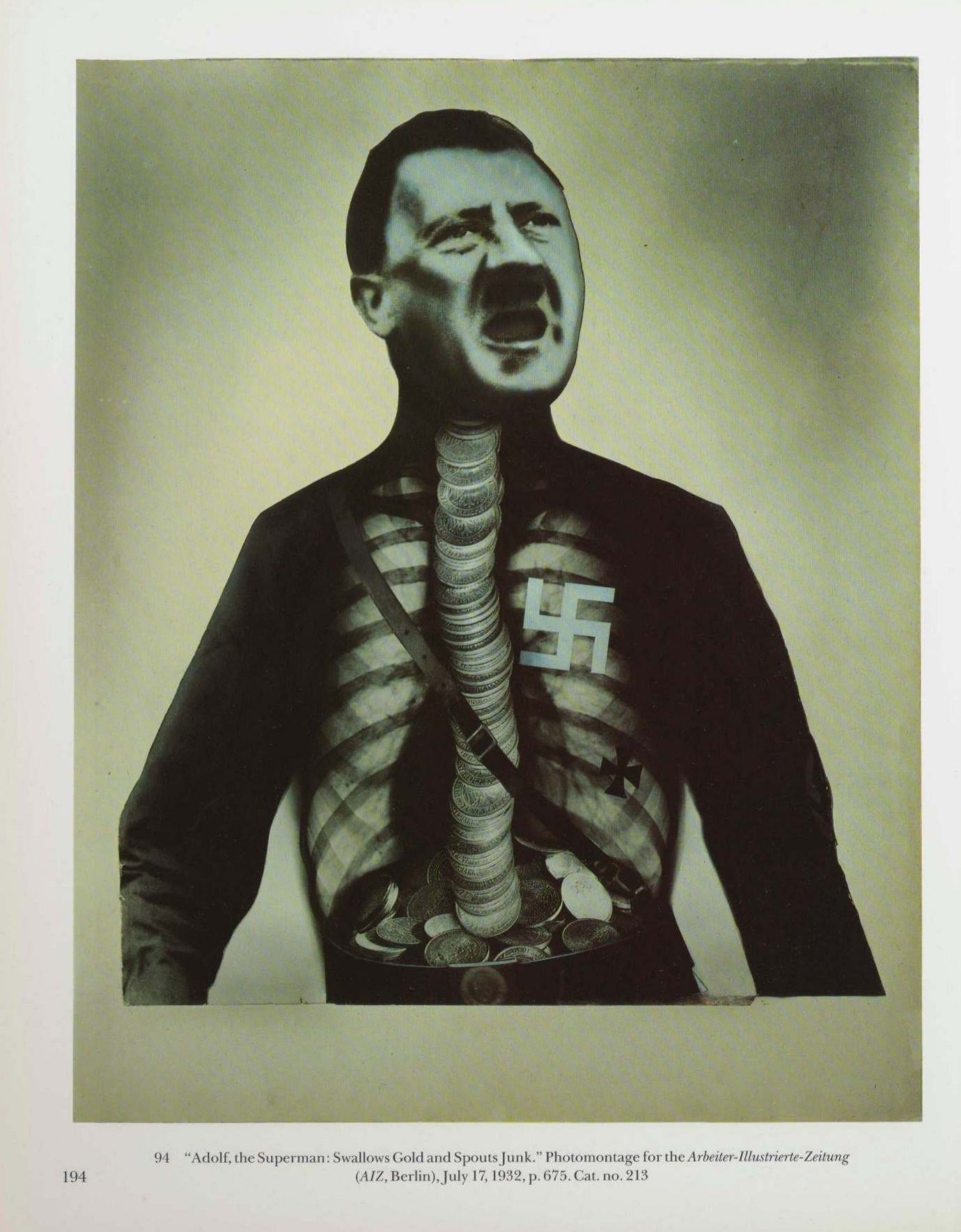

Heartfield was a master of bitter, satiric art. Using images from newspapers, magazines, and advertisements and juxtaposing incongruous details, he created startling pictures with strong meanings. Many of his photomontages appeared in the German leftist newspaper AIZ (Arbeiter-Illustrierte-Zeitung, or Workers’ Illustrated Newspaper) between 1930 and 1938; they remain powerful even today, instantly comprehensible although they deal with figures and events of more than half a century ago.

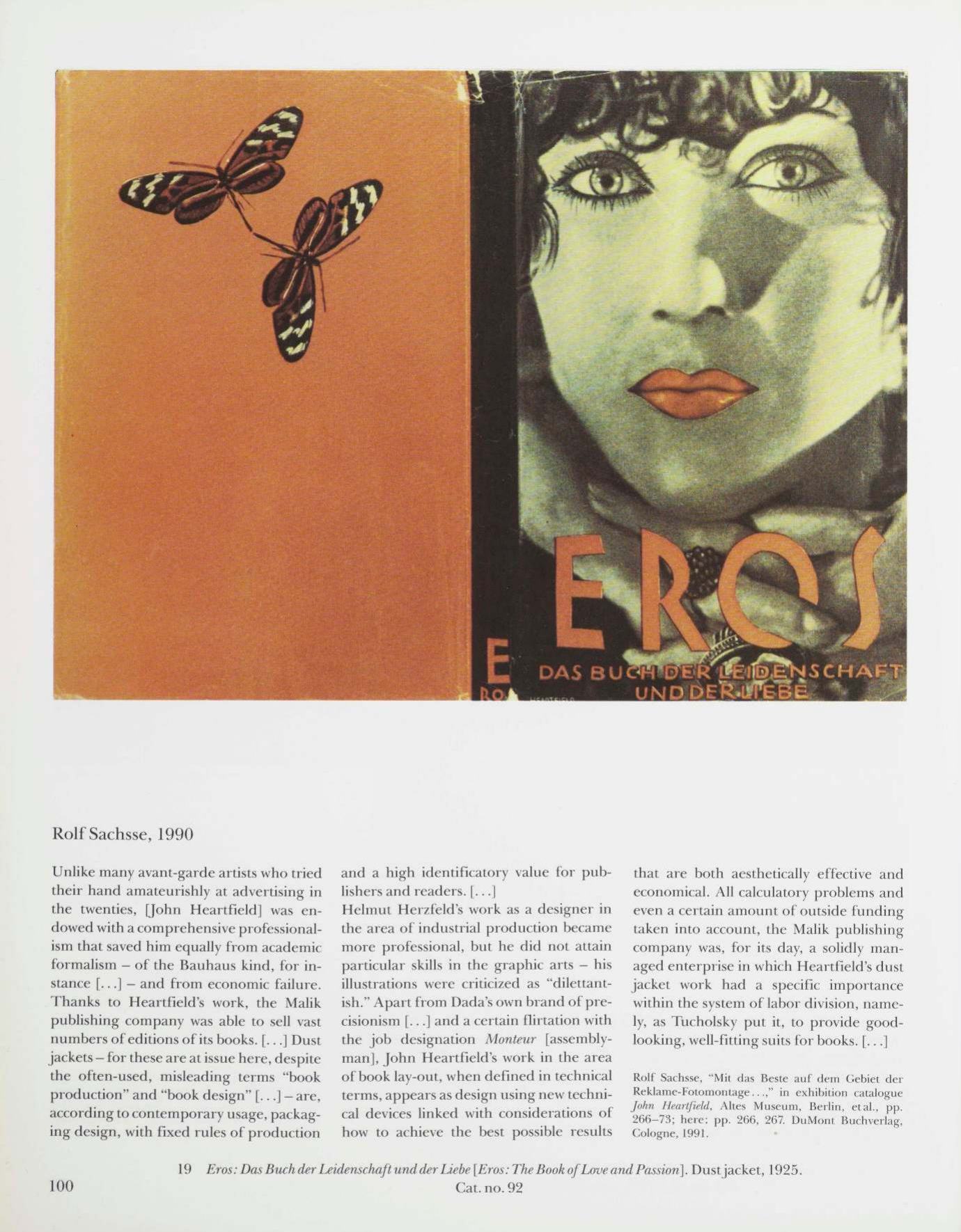

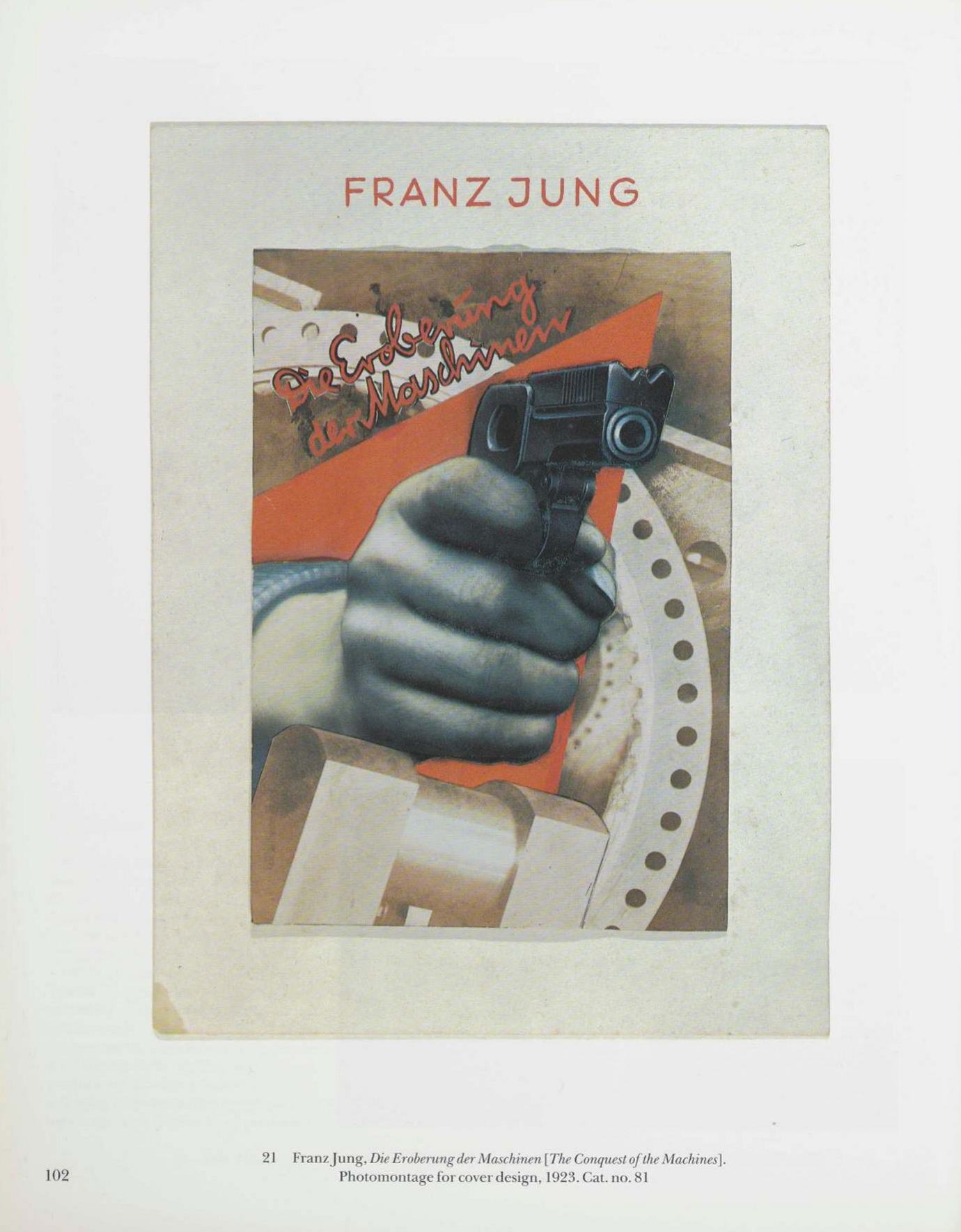

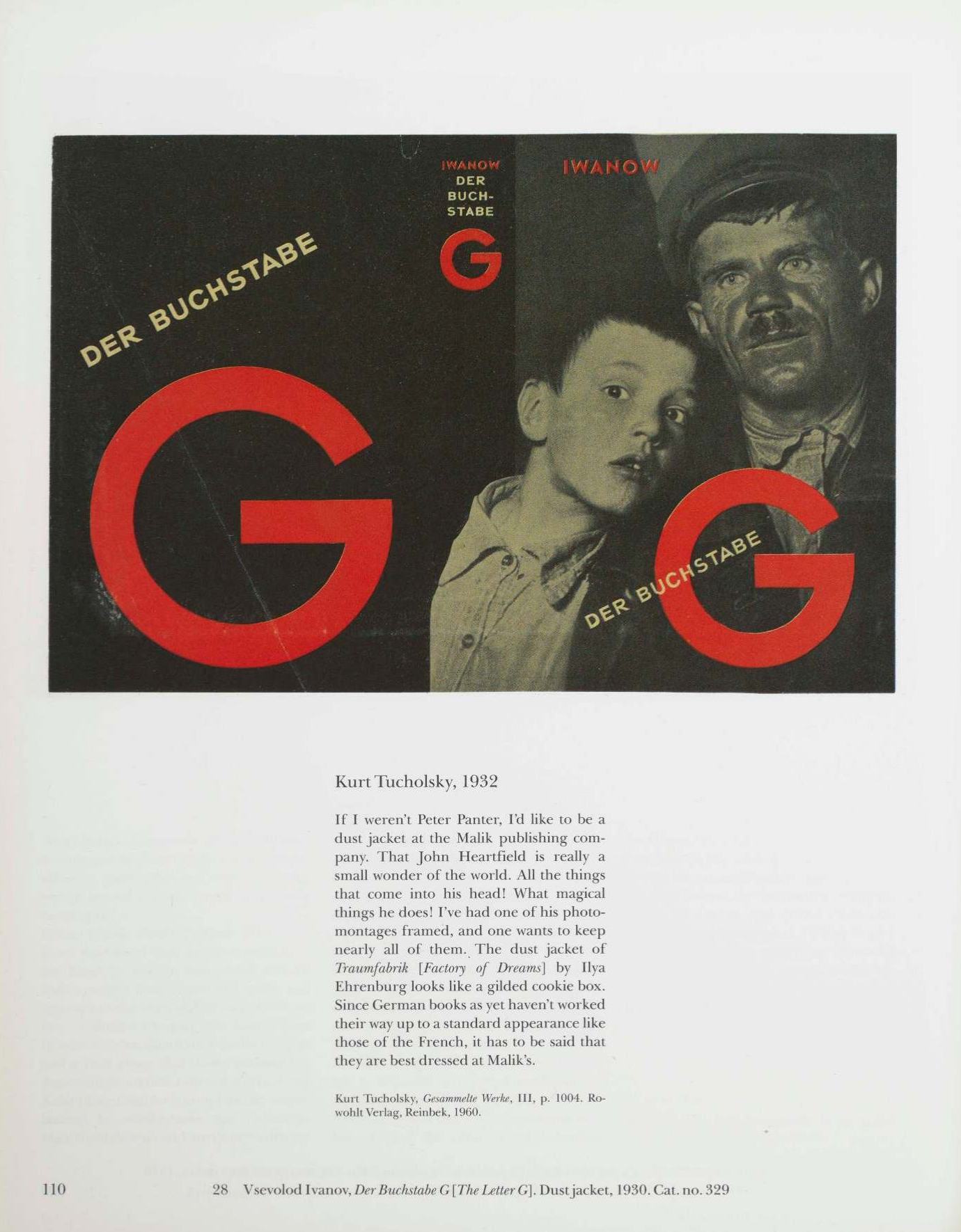

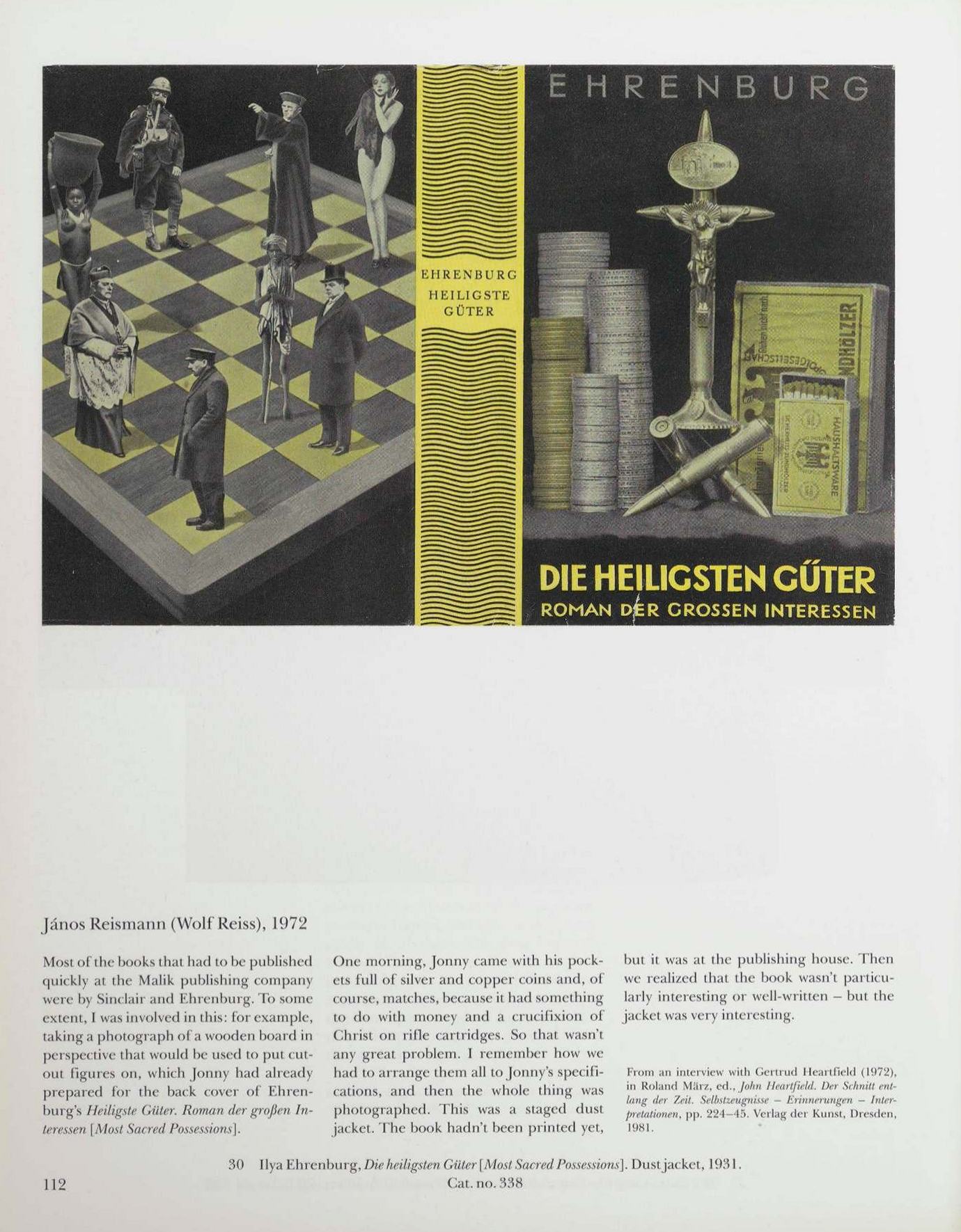

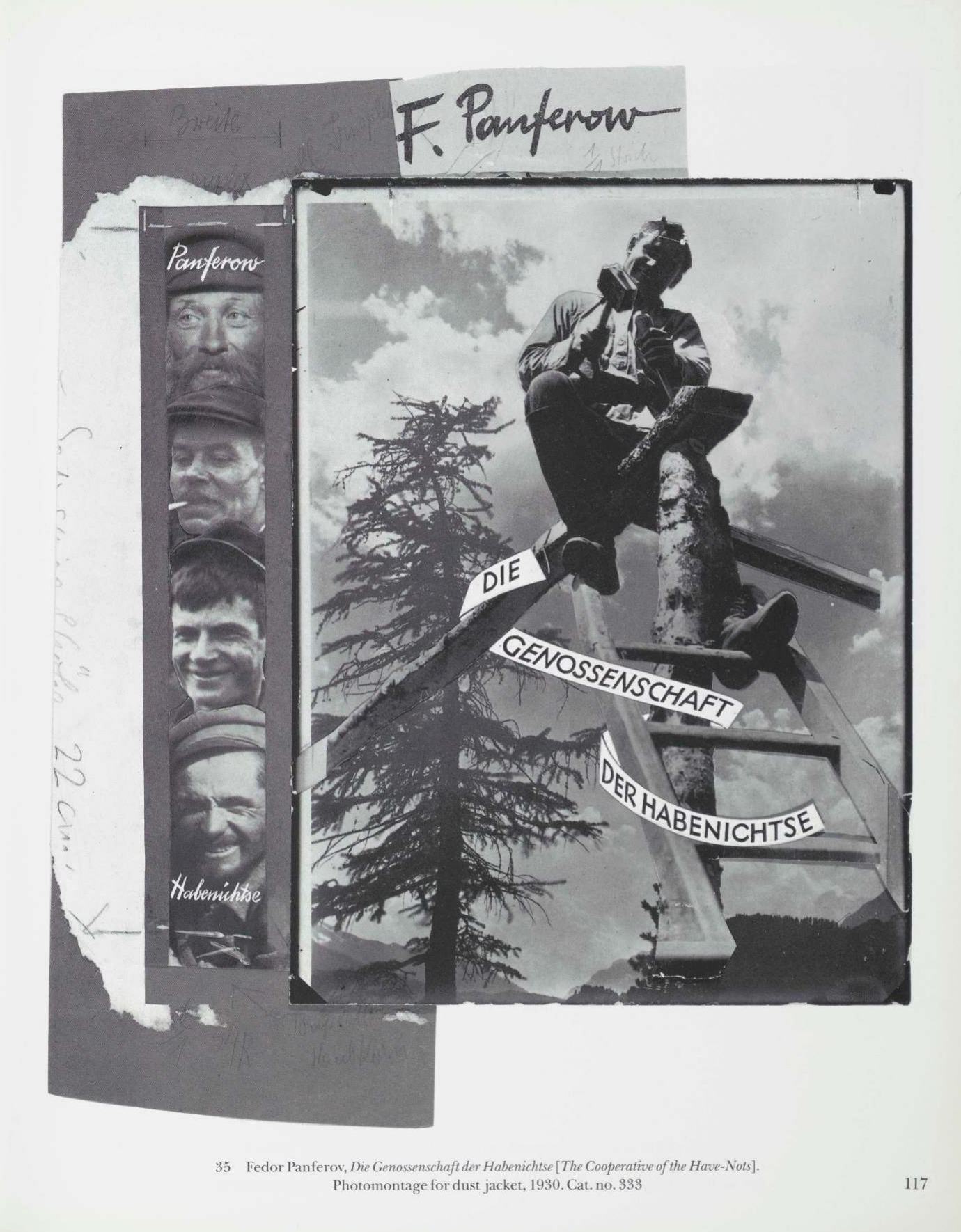

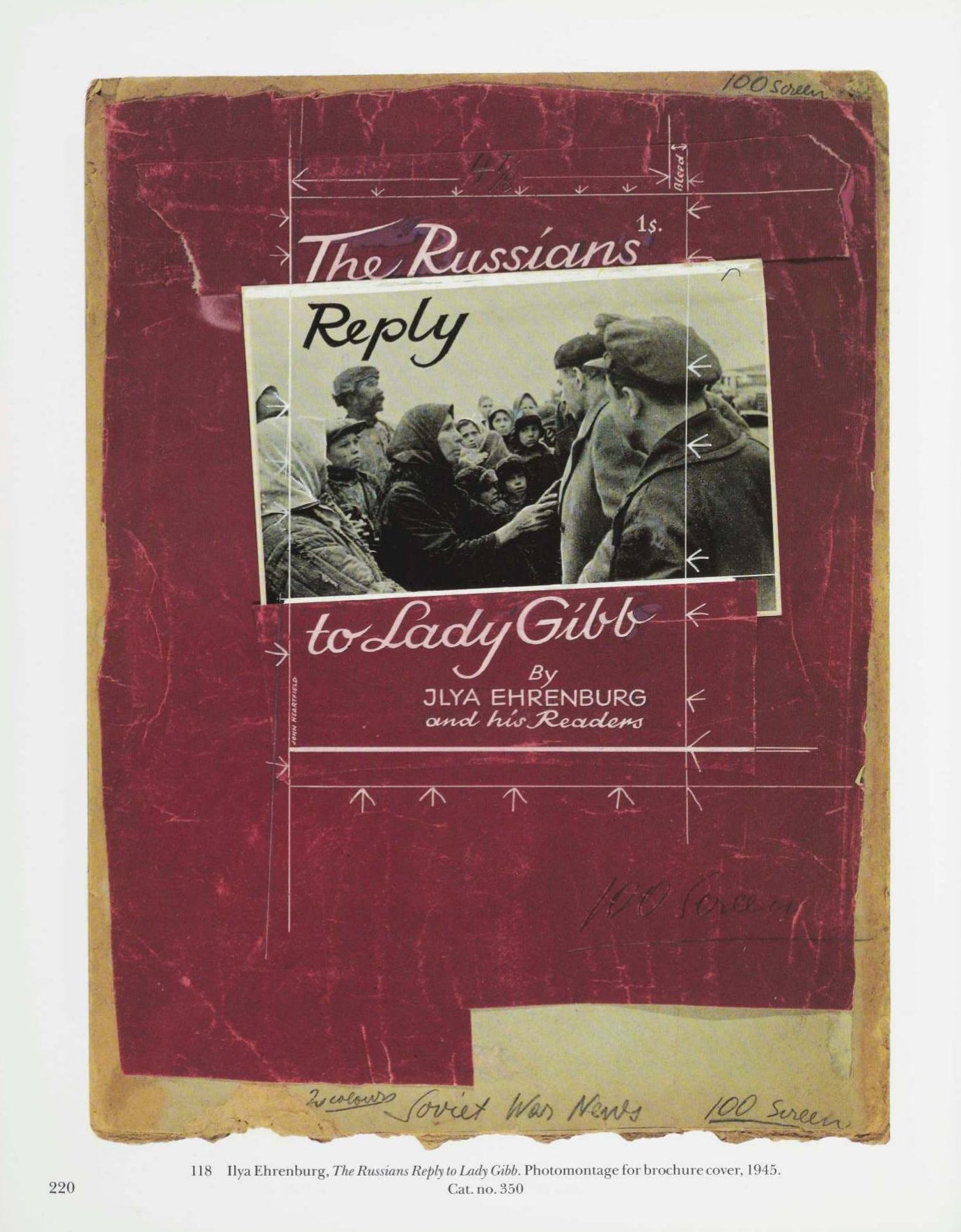

Heartfield also became known for his strikingly original book jackets, which he designed for his brother’s publishing firm, Malik-Verlag, for works by such authors as Upton Sinclair, John Dos Passos, and Ilya Ehrenburg. He placed images on the front and back of the jackets to instantly convey the books’ content. This was a dramatic departure from the plain book jackets of the period.

Forced to flee Germany after Hitler came to power, Heartfield continued to create work for the AIZ while in exile. He spent the war years in England, where he eventually found work as a graphic artist for publishers such as Penguin Books and Lindsay Drummond. As an active supporter of Communism, Heartfield returned to what was then East Germany in 1950. After some years without recognition, he was finally honored by the state, and for the first time in his life he was supported by the existing political regime.

This extensively illustrated volume is the most comprehensive study yet published of the artist’s work. Heartfield’s Dada pieces, virulent photomontages, posters, theater sets, and book designs show brilliantly his technique of combining ironic political slogans with stirring imagery. His life and career are placed in historical context, with the use of documents and letters, by a number of eminent scholars led by Peter Pachnicke and Klaus Honnef, who based their work on the material in the Heartfield archive in Berlin.

John Heartfleid is published to accompany a major exhibition of the same name that originated in Germany before traveling to London, Dublin, Edinburgh, New York, San Francisco, and Los Angeles.

289 illustrations, including 83 plates in full color.

Foreword

We are now so used lo the ubiquitous use of photomontage in advertising and other forms of propagandistk artwork that we find it hard to conceive of them without its witty, disruptive, or startling contribution. We are no longer surprised to see two or more different realities juxtaposed in the same image. The satirical and the surreal have become part of our way of thinking about and seeing the world. We are suspicious of an homogeneous image and almost automatically try to deconstruct it, to try and show the true realities that lie behind its seamless surface. If the Surrealists have taught us to seek out the hidden sexual motives of human behaviour, John Heartfield has shown the base materialism of so much political power, the links between war and money. No one has been more effective than Heartfield in exposing the lies of fascist politicians. His work speaks powerfully to us today despite the intervening half century and more. The basic subjects which he treats – war, poverty, political misuse of power, injustice – have not disappeared from the world. They are still unfortunately universals that can arouse feelings of pity, fear, and anger.

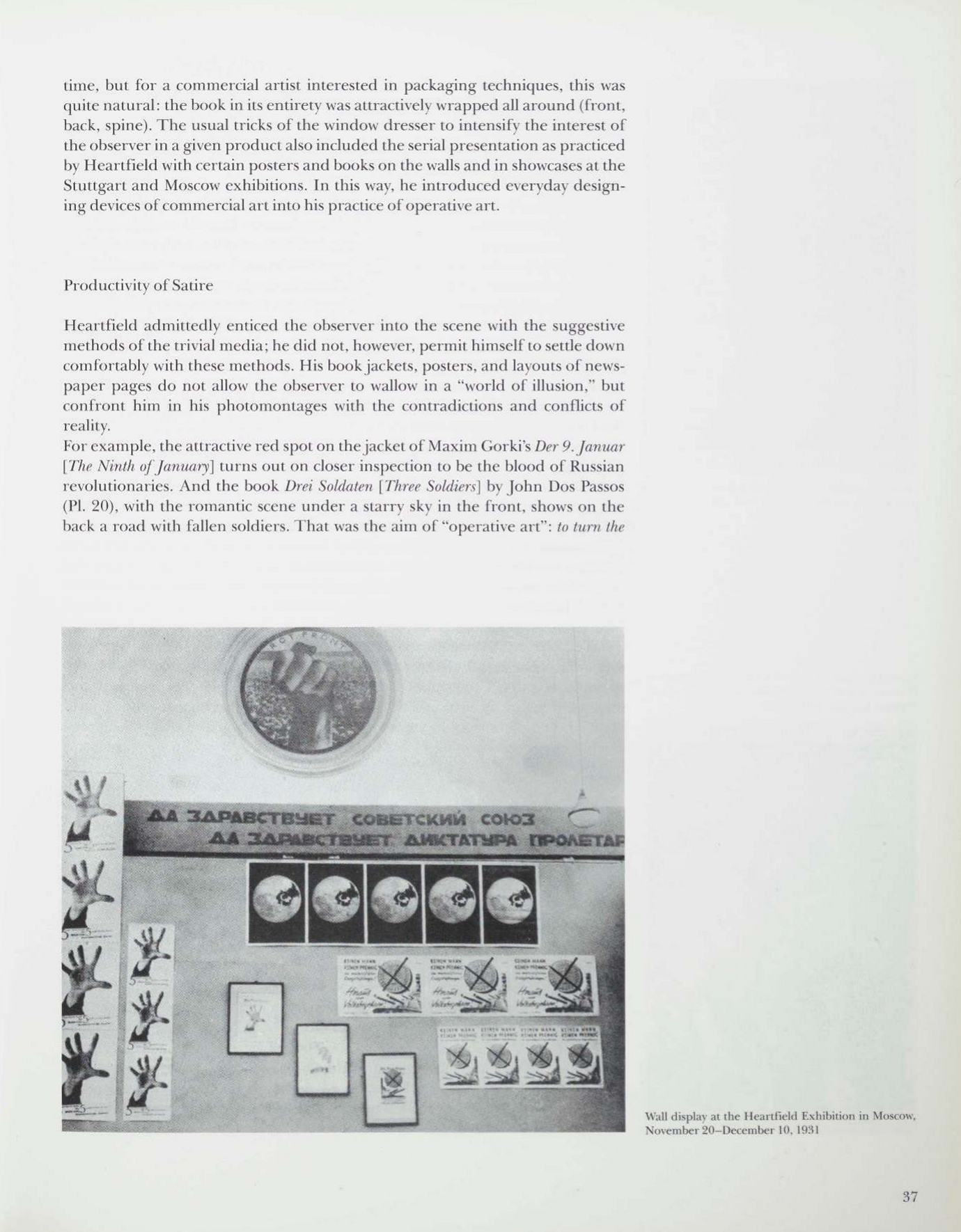

We are extremely pleased to be able to present this major exhibition of Heartfield’s work that shows not only the range of his achievements, from political satire to book covers, from posters to theatre sets, but how he achieved the eye-deceiving brilliance of his montaged images. For the first time in a touring exhibition Heartfield’s original montages will be shown, thus allowing an unique opportunity to observe his working methods at close quarters. In addition the recreations of the First International Dada Fair held in Berlin in 1920 and of the FILM UND FOTO exhibition held in Stuttgart in 1929 will show the importance that Heartfield (and his colleagues) gave to the installation of his works, so as to achieve their maximum impact.

We would like to take this opportunity of thanking the Director of the Akademie der Künste zu Berlin for lending works so generously from their Heartfield Archive and the Director of the Berlinische Galerie for lending works connected with the 1920 Berlin Dada Fair. The exhibition has been conceived and planned by Dr. Peter Pachnicke and Dr. Klaus Honnef. We wish to thank them in particular for helping to edit the English-language version of the catalogue. Through all the stages in the planning and realisation of this exhibition Dr. Beate Reisch of the Akademie der Künste zu Berlin has been an invaluable colleague. We are very grateful to her.

Heartfield (who anglicised his name from the German Herzfeld as a protest against nationalism during the First World War) spent the years from 1938 to 1950 as a refugee in London. The impact and appreciation of his art were limited at that time. We hope that this exhibition will do much to broaden an awareness in Britain and Ireland of the contribution he made to an uniquely twentieth-century art form.

John Hoole, Curator

Barbican Art Gallery, London

Declan McGenagle, Director

The Irish Museum of Modern Art, Dublin

Richard Calvocoressi, Keeper

Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh

Foreword

For scholars of avant-garde and early twentieth-century art John Heartfield represents the quintessential operierende Künstler (activist-artist). To many he embodies the very notion of the engaged critical artist. He is, in essence, an early model of the artist whose singular oppositional voice carries for us all the banner of social and political conscience. As a Dada provocateur, Heartfield worked to undermine the very notion of art as a purely aesthetic entity separated from the fabric of the society in which it is produced. In his efforts to disseminate information to the public, Heartfield made extensive use of photomontage and was, indeed, one of the first artists to use the techniques of the mass media to question, probe, and satirize the growing tyranny of a political regime. Through his innovation of combining contradictory images into spatially unified compositions, Heartfield created a means of communication that was uncompromising in its harsh directness.

In the politically fragile and tumultuous world of today, the role and significance of art and the artist is again being questioned, and it is perhaps in looking at Heartfield’s work that lessons of the past can be applied to the present. His politicizing of art and use of the mass media as a critical tool have a special relevance to the contemporary practice of many European and American artists. Nevertheless, for all the art-historical importance scholars have assigned to Heartfield, few exhibitions have been devoted to his work, and it is with special pride that we are pleased to present the first extensive showing of John Heartfield’s photomontages to the American public.

We are grateful to Dr. Beate Reisch of the Akademie der Künste zu Berlin for her unsparing efforts in bringing this exhibition to the United States and to Dr. Peter Pachnicke, Dr. Klaus Honnef, and Mr. Hans-Jürgen von Osterhausen for their help in organizing this project. The members of the editorial and production staffs of DuMont Buchverlag, particularly Karin Thomas and Peter Dreesen, and the editorial staff at Harry N. Abrams, Inc. made essential contributions to this publication. Without the enthusiasm and professional commitment of the responsible curators at our respective institutions – Magdalena Dabrowski of The Museum of Modern Art, Sandra Phillips of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, and Stephanie Barron of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art – this exhibition might not have been seen in this country, and they all deserve our warm thanks. Finally, The Museum of Modern Art is deeply appreciative to The Robert Lehman Foundation, Inc., for generously supporting the presentation in New York.

Richard E. Oldenburg, Director

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

John R. Lane, Director

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

Earl A. Powell, III, Director

Los Angeles County Museum of Art

June 1992

Heiner MüllerOn Heartfield

John Heartfield is a classic artist in the sense that his work had impact, more in the arts than in politics: German workers, to whom it was primarily addressed, preferred dancing fairies or bellowing stags at the edge of the woods to Heartfield’s photomontages. The dictators of the century had the same conception of art, with the exception, perhaps, of Mao Tse-tung: after all, he loved Immensee just as Napoleon loved Werther. Even the majority of visual artists at the Academy of Arts in the German Democratic Republic needed seven years to accept Heartfield’s work as art, to accept the assemblyman [Monteur] as artist. His photomontages are part of the class warfare of his day, but they are not only documents that keep alive the recollection of the past. They gain in substance from hatred of injustice, just as Tintoretto’s frescoes gained in substance from belief in salvation, a new beauty that can be used for other things. The first lines of Brecht’s unsuccessful attempt to cast the Communist Manifesto in poetry: Kriege zertrümmern die Welt und im Trümmerfeld geht ein Gespenst um [Wars are wrecking the world, and a spectre is haunting the ruins], in perfect verse remain in one’s memory, even if the spectre of communism will probably never materialize. The empires, as well as the cults that are committed to it, come and go; the statues remain. That sentence loses some of its solace with each new war. Recollection of the past presupposes the survival of the species, which is now endangered; the liquidation of the planet is in progress. Surgical war should not be the last resort in order to save the memory of mankind—works of art.

Peter Pachnicke, Klaus HonnefOn the Subject

In 1939, John Heartfield was honored in England with the exhibition One Man’s War Against Hitler. In fact, this vivacious, little, five-foot-two David had openly challenged the fascist Goliath with his satirical picture montages and was the only one, with the exception of Charlie Chaplin, who was able to make a laughing stock out of him.

When he returned from emigration in England in 1930, we Germans, though, put our hero in cold storage for the time being. During the Cold War, the petty-minded opportunists, who solicitously sought to placate the victors’ standards and enemy’s profiles, were incapable of realizing and comprehending Heartfield’s genius. In the West, he was ignored because he was a communist and did not express himself in the international idiom of abstract art.; in the East, he was accused of cosmopolitan formalism because, in giving socialism a sensual countenance by means of avant-garde art, he contravened the know-it-all state-ordered doctrine of art, according to which the artist could make himself comprehensible to the man on the street only in the form of nineteenth-century genre painting.

Heartfield was still able to experience the renaissance of his work during the thaw of the sixties. Due to the unwavering commitment of, above all, his brother Wieland Herzfelde and his friends Brecht, Heym, Uhde, and others, a comprehensive Heartfield exhibition was finally held at the Academy of Arts in the German Democratic Republic in 1957, and in 1962 a monograph, still valid today, was published by the Verlag der Kunst, Dresden. He also received all kinds of government distinctions and tributes. In exhibitions that he arranged himself, his works were sent out around the world as ambassadorial messages from an anti-fascist state – thus reaching the other Germany. If Heartfield’s fate in the German Democratic Republic at that time was more that of the ineffectual classic artist, he certainly struck the nerve of a generation in the German Federal Republic during those years. He became a father-figure for the generation of 1968. His operative conception of art, whereby art should not be shut up in the seclusion of the museum but should instead strive to be active in the political day-to-day life of the street and in the mass media, was for them a basic model for the emancipation of a truly democratic, socialist society.

These dreams did not blossom in the West, and real socialism, in whose all-liberating power Heartfield staunchly believed until his death, is now in a phase of tragic, tragicomic self-destruction. In the year of John Heartfield’s centennial birthday, his works will therefore have to speak for themselves. The philosophy of this exhibition is to put these works under scrutiny – not just examine how they function within the operative conception of art. The starting place was the Heartfield Archive of the Akademie der Künste zu Berlin, where virtually all the designs for his photomontages as well as their printed reproductions in newspapers, magazines, on dust jackets and posters are preserved. Intensive study of the original montages has made it clear that Heartfield’s works were not only of agitatorial use for the cause of the revolution, but, when released from the concrete historical situation, also prove to be varied and ambivalent artistic creations reflecting and penetrating the totality of a world full of contradictions. In this exhibition and catalogue we endeavored to present in a tangible way the original montages in their refined graphic structure and the reproductions from the AIZ (Arbeiter-Illustrierte-Zeitung) [Workers’ Illustrated Newspaper] in their abundant tonal values. We did so to make it clear that Heartfield’s montages did not – like a well-told joke – simply combine picture and text in a provoking manner. For him, montage was more a symbolic form in which, apart from photos and texts, tonal values, the colors and structure of the material, the precisely calculated organization of the visual plane, and the imaginary visual space devised by means of retouching produced many levels of meaning. Heartfield is not being aestheticized. Instead, the diversity and ambivalence of his montages become obvious. Thus his works extend beyond political current events, allowing the viewer to develop his thoughts, imagination, and sensual perceptiveness. The fact that the current political trend has not faded is assured by reality itself, which tries even nowadays to live up to the satirical montages in a violent and impertinent manner.

The debate in the press during this exhibition in Berlin and Bonn demonstrates just how solidified prejudices are when the subject concerns Heartfield in Germany. The Left complained that the exhibition aestheticized Heartfield’s work. The Right contended that the exhibition only confirmed its firmly held opinion that Heartfield was nothing more than a clever propagandist of communist ideology. There is no doubt that Heartfield was a dyed-in-the-wool communist. There is even much less doubt that he handled art as a weapon: against bigoted conservatives, against Nazis and fascists, and even against Social Democrats. Heartfield was a typical representative of the German intelligentsia in the Weimar Republic.

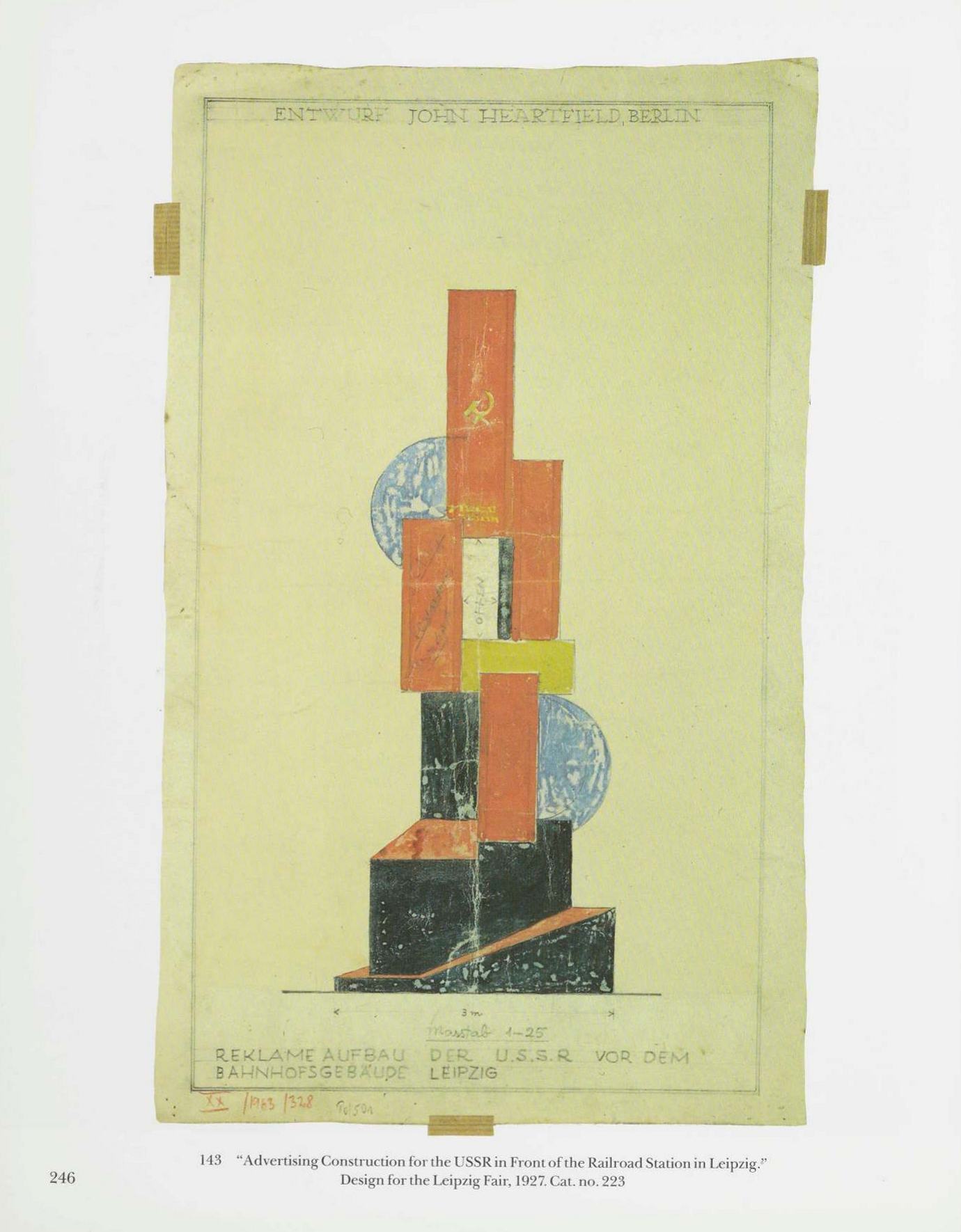

Heartfield was a rigorous moralist and an aesthetic fireball. This at least is emphatically seen in this exhibition. He consistently used a wide range of artistic media of the day for his political and aesthetic ideas – the new media of film and photography, illustrated magazines published for the masses, the theatre. He was an artist to whom impact mattered. He was not one of those whose only ambition is to go down in the annals of art history. Nevertheless, Heartfield is one of the great figures in the history of German art in the twentieth century. He was certainly the first German artist who was capable of looking beyond conventional practices and, as a matter of Tact, anticipated most of what is now celebrated as innovation: interrelated media and disciplines. Heartfield did not think, feel, or work in such divergent terms as fine or commercial, legitimate or illegitimate, high or low art. He took every job with equal seriousness, regardless of whether it was an advertisement, a dust jacket, a newspaper, a stage set, or a display. Every aspect of everyday living was also to be aesthetically revolutionized, and was to acquire a face and body in which people could also see the NEW with their own eyes, hear it with their own ears, taste it with their own mouths, smell it with their own noses, and touch it with their own hands. He was not only the most significant satirist of the German plight; he would have been the most significant designer of a socialist world had he been, to use his own words, “left alone to do it.”

The idea for this exhibition originated in 1988. It did not need to be altered in the period of political change because it came from the Akademie der Künste specifically from Heiner Müller. This exhibition would not have been possible without the special political and financial involvement of the Landesregierung Nordrhein-Westfalen, the Landschaftsverband Rheinland, the Foundation for Art and Culture of the State of North Rhine-Westphalia, as well as the Ministry of the Interior of the Federal Republic of Germany.

The overall organization of the project was in the hands of Beate Reisch on behalf of the Akademie der Künste zu Berlin, and Hans-Jürgen von Osterhausen at the Landschaftsverband Rheinland. The staff of the Heartfield Archive, above all Elisabeth Patzwall, Michael Krejsa, Petra Albrecht, and Lia Manouri, have made a variety of scholarly and archival contributions. The first reconstruction of the Heartfield Room from the Stuttgart FILM UND FOTO exhibition is the scholarly merit of Elisabeth Patzwall. The interpretation of the Dada Fair on the basis of the Stationen der Moderne exhibition was rendered by Helen Adkins and supported by generous loans from the Berlinische Galerie, Berlin.

The editors thank the staff of DuMont Buchverlag, Karin Thomas, Winfried Konnertz, and Peter Dreesen, who supervised the editorial work, the layout, and the technical production of this catalogue with tremendous personal commitment. Thanks go also to Nora Beeson and the staff of Harry N. Abrams, Inc. for the English edition.

Additional thanks go to Dieter Route of the Sprengel Museum in Hannover, Götz Adriani, of the Kunsthalle Tübingen, and especially to Magdalena Dabrowski of The Museum of Modern Art in New York, and to all the museum directors and curators who are showing this exhibition in London, Edinburgh, Dublin, New York, Los Angeles, and San Francisco.

The editors are especially pleased with the extraordinary interest shown by prominent art institutions abroad, not only because Heartfield is finally receiving the international recognition that his work deserves, but also because it can prove abroad what a diverse intellectual heritage the reunified Germany possesses.

John Heartfleid, 1967

[...] how I got the idea of making photomontages. I’d say [...] I started making photomontages during the First World War. There are a lot of things that got me into working with photos. The main thing is that I saw both what was being said and not being said with photos in the newspapers. The most important thing for me was that I intrinsically became involved in the opposition and worked with a medium I didn’t consider to be an artistic medium, photography. [...] I found out how you can fool people with photos, really fool them. [...] You can lie and tell the truth by putting the wrong title or wrong captions under them, and that’s roughly what was being done. Photos of the war were being used to support the policy to hold out when the war had long since been settled on the Marne and the German army had already been beaten. [...]

I was a soldier from very early on. Then we pasted, I pasted and quickly cut out a photo and then put one under another. Of course, that produced another counterpoint, a contradiction that expressed something different. That was the idea. It still wasn’t all that clear to me where it would lead to, or that it would lead me to photomontage.

From a conversation with Bengt Dahlbäck (Moderna Museet, Stockholm)

Table of Contents

Foreword.. 7

Foreword.. 8

Heiner Müller

“On HeartField”.. 9

Peter Pachnicke / Klaus Honnef

“On the Subject”.. 10

Nancy Roth

“Heartfield and Modern Art”.. 18

Peter Pachnicke

“Morally Rigorous, Visually Voracious”.. 32

Klaus Honnef

“Symbolic Form as a Graphic Cognitive Principle: An Essay on Montage”.. 49

Catalogue.. 65

Hubertus Gassner

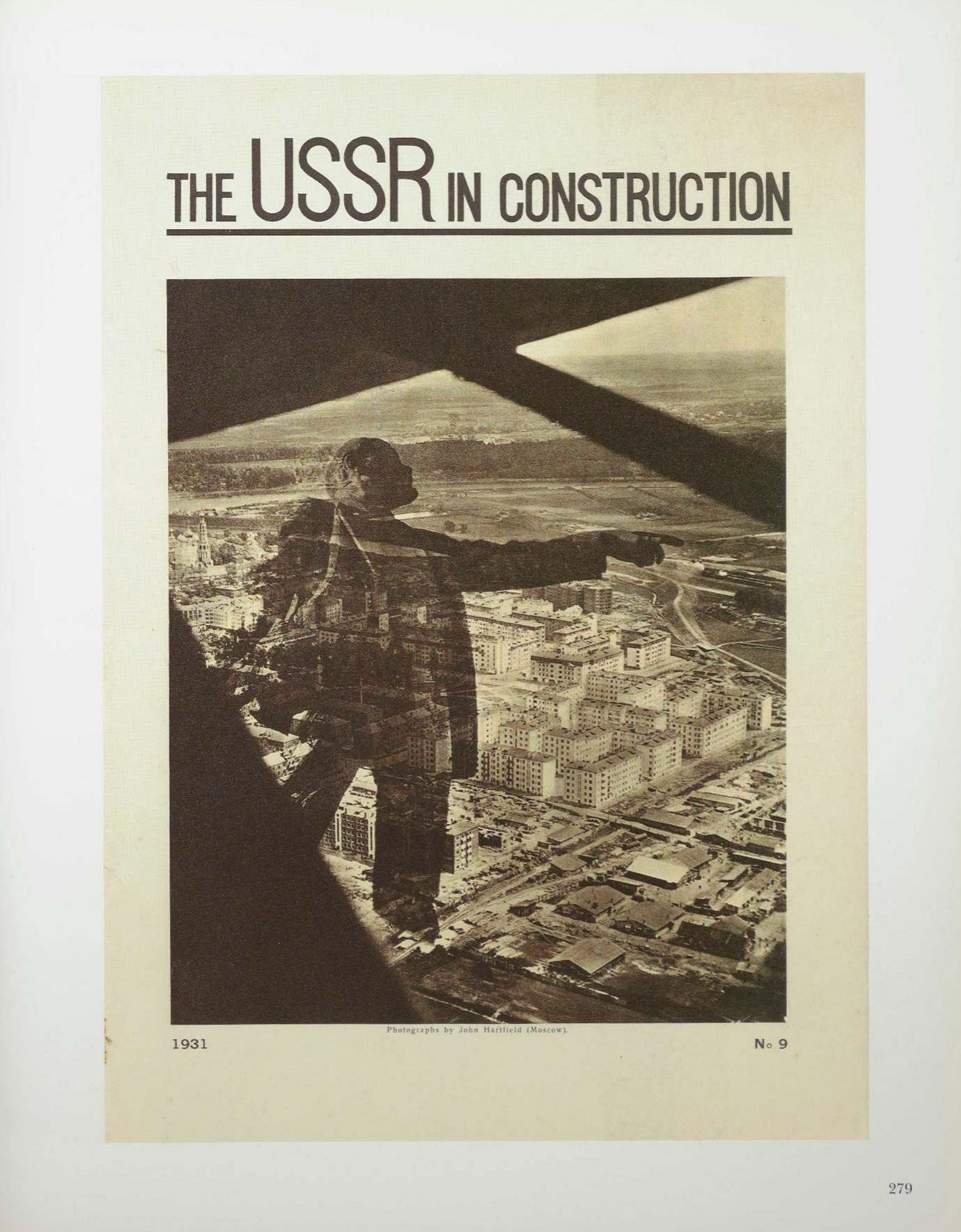

“Heartlield’s Moscow Apprenticeship, 1931—1932”.. 256

Sergei Tretyakov

“Montage Elements”.. 291

Michael Krejsa / Petra Albrecht

“Biographical Chronology”.. 300

Checklist of Exhibited Works.. 319

Selected Bibliography.. 338

Index.. 339

Photographic Credits and Copyrights.. 342

Sample pages

Download link (pdf, yandexdisk; 100 MB)

Source: MoMA

Все авторские права на данный материал сохраняются за правообладателем. Электронная версия публикуется исключительно для использования в информационных, научных, учебных или культурных целях. Любое коммерческое использование запрещено. В случае возникновения вопросов в сфере авторских прав пишите по адресу 42@tehne.com.

12 сентября 2019, 10:33

0 комментариев

|

Партнёры

|