|

|

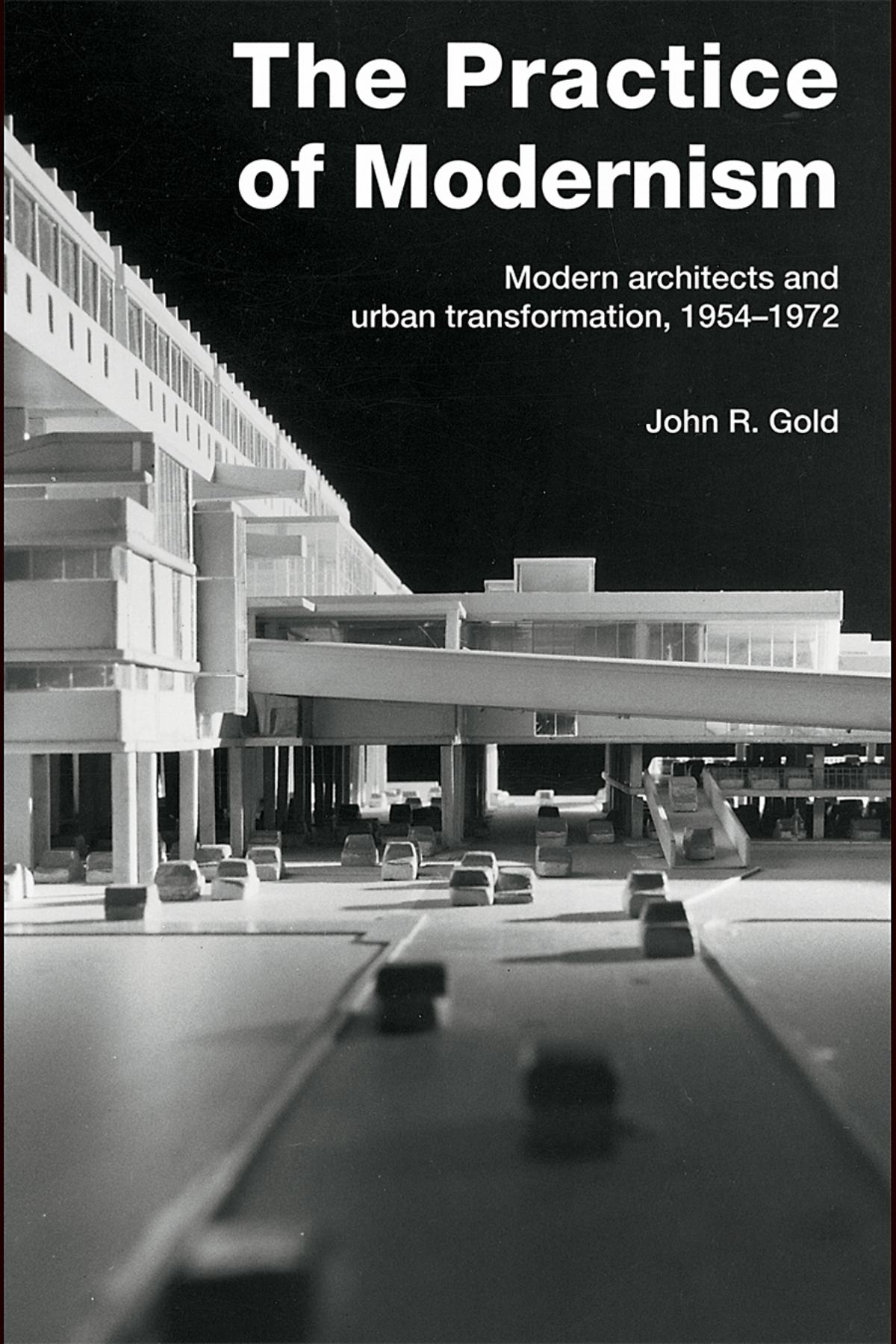

John R. Gold. The Practice of Modernism : Modern architects and urban transformation, 1954–1972. — London ; New York, 2007  The Practice of Modernism : Modern architects and urban transformation, 1954–1972 / John R. Gold. — London ; New York : Routledge, 2007. — XVI, 336 p., ill. — ISBN10: 0–415–25842–1 (hbk) ; ISBN10: 0–415–25843–X (pbk) ; ISBN10: 0–203–96218–4 (ebk)The Practice of Modernism

The postwar period saw greater change in the appearance, structure and skyline of cities than any comparable period in modern history. During the late 1950s and the 1960s, municipal councils routinely devised and implemented radical schemes to reshape and modernise their towns and cities. This book, following on from the author's widely acclaimed The Experience of Modernism, traces the involvement of modern architects in this process.

Making extensive use of primary documentation and in-depth interviews with architects of the time, The Practice of Modernism examines the intricate relationship between vision and subsequent practice in the saga of postwar urban transformation. The first part of the book traces the personal, institutional and professional backgrounds of the architects involved in schemes for reconstruction and replanning. It then goes on to deal directly with the progress of urban transformation, focusing on the contribution that modern architects and architectural principles made to town centre renewal and social housing. Finally, the book highlights how the exuberance of the 1960s gave way to the profound reappraisal that emerged by the early 1970s.

At a time when popular understanding of mid-twentieth century urban transformation remains clouded by generalisation and blanket condemnation, The Practice of Modernism provides an incisive and timely view of the true complexity of the processes and agencies that brought about change. It will interest urban and architectural historians, urban geographers, planners and all concerned with understanding the recent history of the contemporary city.

John R. Gold is Professor of Urban Geography and a member of the Institute for Historical and Cultural Research at Oxford Brookes University.

Contents

List of figures viii

List of tables xi

List of illustration credits xii

Preface xiii

1 On the threshold 1

2 Practising modernism 18

3 Public and private 42

4 Professions 61

5 Towards renewal 77

6 Heart and soul 105

7 Second generation 146

8 The pursuit of numbers 165

9 With social intent 204

10 Succession 228

11 Late-flowering modernism 246

12 Storm clouds 270

Notes and references 290

Index 329

Preface

In 1963, my family was on an outing to central London. As we headed back to where the car was parked off Tottenham Court Road, I looked up at the emerging skeleton of a building under construction at what appeared to be an enormous traffic island at the junction of New Oxford Street and Charing Cross Road. 'What are they building?' I asked. 'I'm not sure', said my Mother, 'but there are a lot of new flats and offices going up. You won't be able to recognise the place soon.' Recalling that now, it sounds like there should have been a wistful tone in her voice – noting the passing of an era as the historic city in which she was brought up was ripped apart. Yet, as far as I can remember, she said it in a perfectly matter-of-fact sort of way. She was neither excited nor alarmed at the prospect. This was just the way of the world at that time. Things were irrevocably changing, or so it seemed, and the city was changing with them. This was progress, change was normal, and cities needed to be brought up-to-date to match the new sensitivities.

Normality, however, has a habit of being a strangely short-term phenomenon in the world of urban development. Within a short space of time, those 'new sensitivities' were themselves under scrutiny and attack. The structure to which I had addressed my chance remark was none other than Centre Point, the office block built at the site of a proposed, but shortly to be abandoned, traffic roundabout. Centre Point, which remained vacant for many years due to anomalies in the financing and rating of property development, was a powerful symbol. Not only was it a good example of what Ted Heath might have considered the 'unacceptable face of capitalism', but also it was a highly visible symbol of the ills of urban renewal. By the end of the decade, there would be other symbols of equal potency. They included Westway, the elevated section of the A40(M) roadway that divided communities in the west of the city; Ronan Point, the partially collapsed tower block in Canning Town that prompted far-reaching inquiries into the condition and safety of system-built public housing; and the Coal Exchange and Euston Station's Doric arch – two important historic structures demolished because they happened to stand in the way of developers' plans. Each became an emblem of resistance for those who opposed the accepted approaches for redesigning the modern city. Each too, in widely differing ways and with varying degrees of fairness, could be associated with the application of architectural modernism.

London's experience was not unique. Many other British cities witnessed the same cycle in which the peak of enthusiasm for things associated with modernism turned sour within a remarkably short period. Similar protests were experienced elsewhere, particularly in the older cities of the USA, as groups concerned about the transformation of the urban environment started to challenge the prevailing orthodoxies and the values that lay behind them. The trend proved infectious. Inner-city neighbourhoods threatened with clearance saw campaigns mounted that, just occasionally, held off the developers. A number of recently redeveloped housing estates, both low- and high-rise, started to show patterns of social disorder that called into doubt aspects of renewal policy. What started as sporadic protests over specific issues consolidated into something larger that challenged the accepted policies of planned urban reconstruction and undermined the authority of architects and planners deemed responsible for them. 'Modernism', however nebulously defined, became characterised as the derided inspiration for the architecture of another, now happily concluded, phase in the life of cities. Indeed, it was well on its way to becoming the dragon that a new generation of critics queued up to slay.

This dramatically changing climate of opinion provides a backdrop to the ideas, processes and events discussed in this book. In essence, this is the second part of a personal inquiry into the experience of architects, who subscribed to a school of thought with many different strands but with a broadly shared sense of direction. My earlier book, The Experience of Modernism, traced the ways in which a group of radical architects and their colleagues in the planning, engineering and quantity surveying professions – loosely referred to as the Modern Movement – staked their claim to a place in helping to design the future city. Dealing with the years 1928–53, it focused on what I termed the 'urban imagination' – the anticipation of future urban forms and patterns of city life – exhibited by those who were part of that movement. This book explores what happened when, at last, those ideas came to influence practice. It focuses on the years between 1954 and 1972 and examines the experiences of those architects, working in the public sector or for private practices, as they thought about or participated in projects destined to transform cities. A further and final book, in what has now become a trilogy, will examine the enduring legacy of modernism – direct and indirect, positive and negative, substantive and mythologised – for architectural thought and practice after 1972.

As with its predecessor, this book draws on oral history and so, when turning to acknowledgements, my thanks go first and foremost to all those who agreed to be interviewed for this study. Given that this book draws on more than fifty lengthy interviews, I hope that the individuals involved will forgive me for thanking them collectively for the time that they spared to be interviewed, for their generous hospitality, for the way that they put me in touch with others who 'you really must talk to...', for the trusting way in which they loaned me personal records and documents – 'bring them back next time you are passing' was the sole condition usually placed on the loan. Without them, this book could not have been written. Naturally I have attempted to follow their wishes, whenever it was indicated that material was sensitive or at points where they requested that there should be no direct attribution of source. At the same time, all interpretations of their testimony, along with any errors of omission or commission, are entirely my responsibility.

Next, a special word of thanks goes to a group of colleagues who also share an interest in the history of architectural modernism in Great Britain. In an academic environment that encourages secrecy and publication at all costs in case other people come across the same ideas, it is extraordinarily gratifying to report the willingness with which scholars in this field of research share information. Miles Glendinning and Stefan Muthesius, for example, allowed me access to the unpublished interview transcripts that they had undertaken in connection with their own seminal research on public sector social housing. These not only yielded valuable nuggets that appear in this text, but also supplied me with a series of important leads that I could pursue further. Much the same may be said for Alan Powers and Elain Harwood. Although both working in this field themselves, they willingly shared with me the names of contacts that they had found valuable and pointed me to sources that I never knew existed. David Whitham kindly gave me access to files and unpublished materials on Cumbernauld and allowed me to take advantage of the considerable amounts of effort that he had already devoted to collecting data about that remarkable New Town.

Particular thanks go to the librarians and curators of the following institutions: the National Monuments Record of Scotland Library (Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland); the Percy Johnson-Marshall Collection (PJMC, Special Collections, Edinburgh University Library); the National Archives (formerly the Public Records Office) at Kew (London); the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA, London) and the Architecture Archives at its new partner the Victoria and Albert Museum (South Kensington, London); the British Library and the National Sound Archive (at St Pancras, London); the British Library (Newspapers Division) at Colindale, London; the London Metropolitan Archives (Clerkenwell); the Canadian Centre for Architecture (Montreal), and the Special Collections Archive at the Francis Loeb Library, Harvard University (Cambridge, Massachusetts). Robert Elwall and Jonathan Makepeace, curators of the RIBA's Photographs Collection, again lavished time on my behalf to find many of the images that accompany this text.

Writing books, of course, needs time. In this respect, I would like to record my thanks to the Arts and Humanities Research Council for the grant of a matched sabbatical under its Research Leave scheme. This allowed the conclusion of the fieldwork and a period of concentrated time to work on the manuscript. This would not have been possible, however, without the grant of sabbatical leave in the first place. I therefore owe a considerable debt of gratitude to Oxford Brookes University for instituting and maintaining its enlightened sabbatical policy and to my colleagues David Pepper, Martin Haigh, Judy Chance, Adrian Parker, Simon Carr, Brad Blitz and Helen Walkington for their support. Avril Maddrell covered my teaching marvellously well during my period of leave. My former colleague George Revill was a major source of encouragement and a welcome fellow traveller throughout the years that we worked together at Brookes. At the start of my research, the late Valerie Karn gave me the benefit of her encyclopedic knowledge of the development of British housing policy. Next in this list come a number of individuals who contributed in many different ways to this book. They include: Mike Barke, Peter Carter, Jon Coaffee, Mary Daniels, Roy Darke, Sir Andrew Derbyshire, Derek Elsom, Clive Fenton, Graeme Ford, Margaret Gold, Sir Peter Hall, Dennis Hardy, Mike Hebbert, Julian Honer, Bob Jarvis, Phil Jones, Peter Larkham, Susan McRae, John Sheail, Colin Ward, Jeremy Whitehand and Sir Colin St. John Wilson. As ever the deficiencies that remain are entirely my responsibility. Maggie, Jennifer, Iain and Josie still somehow seem to put up with me. Finally, this book is dedicated to Stephen Ward, with sincere thanks for his support, collaboration and friendship over the last – whisper it softly – 37 years.

West Ealing, London

Sample pages

Download link (pdf; yandexdisk; 6.0 MB)

The electronic version of this edition is published only for scientific, educational or cultural purposes under the terms of fair use. Any commercial use is prohibited. If you have any claims about copyright, please send a letter to 42@tehne.com.

5 января 2025, 17:18

0 комментариев

|

Партнёры

|

Комментарии

Добавить комментарий