|

|

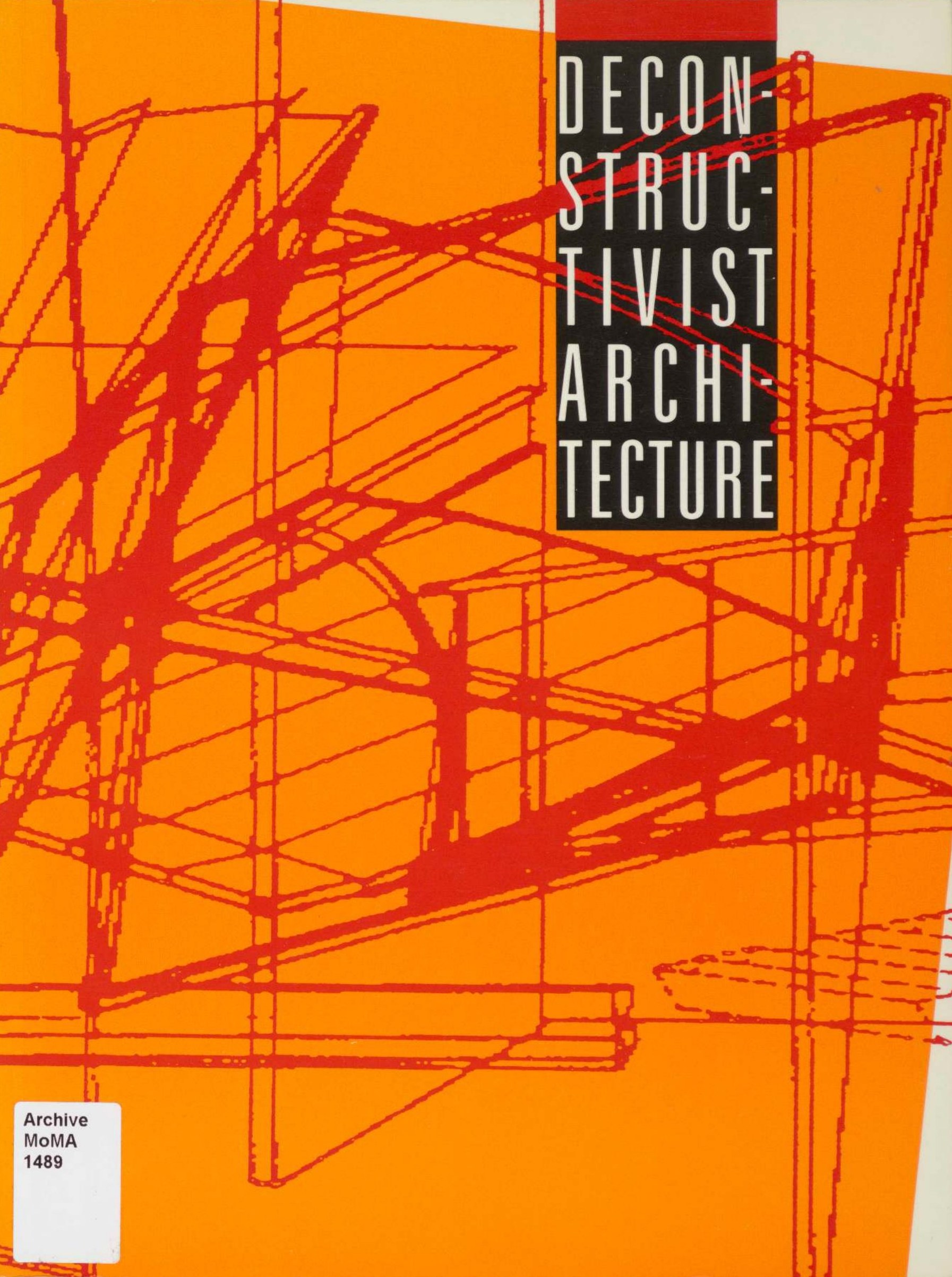

Johnson Ph., Wigley M. Deconstructivist architecture. — New York , 1988Deconstructivist architecture / Philip Johnson and Mark Wigley. — New York : The Museum of Modern Art, 1988. — 104 p., ill. — ISBN 0-87070-298-X

This book presents a radical architecture, exemplified by the recent work of seven architects. Illustrated are projects for Santa Monica, Berlin, Rotterdam, Frankfurt, Hong Kong, Paris, Hamburg, and Vienna, by Frank O. Gehry, Daniel Libeskind, Rem Koolhaas, Peter Eisenman, Zaha M. Hadid, Bernard Tschumi, and the firm of Coop Himmelblau.

Published on the occasion of the exhibition "Deconstructivist Architecture" June 23 — August 30, 1988, directed by Philip Johnson, guest curator, and Mark Wigley, associate curator, assisted by Frederieke Taylor.

Foreword

This book is published on the occasion of the exhibition “Deconstructivist Architecture,” the third of five exhibitions in the Gerald D. Hines Interests Architecture Program at The Museum of Modern Art.

It is with great pleasure that we welcome back Philip Johnson as the guest curator of the exhibition. Having founded the Department of Architecture and Design in 1932, Philip Johnson was also responsible for many of the early landmark exhibitions organized by the department, including “Modern Architecture: International Exhibition” in 1932, “Machine Art” in 1934, and “Mies van der Rohe” in 1947. This is the first exhibition he has done since 1954, when he relinquished the directorship of the department, though the Museum has had the good fortune of having him serve as a Trustee since 1957. He also served as Chairman of the Trustee Committee on Architecture and Design until 1981, and since then has been Honorary Chairman of the Committee. His critical eye and keen ability to discern emerging directions in architecture have once again produced a provocative exhibition. We are also grateful to Mark Wigley, who has been Philip Johnson’s associate in organizing the exhibition, and to the seven architects whose work is featured, for their enthusiastic cooperation.

Finally, we would like to extend our thanks once again to the Gerald D. Hines Interests for their generosity and vision in making this series on contemporary architecture possible.

Stuart Wrede

Director, Department of Architecture and Design

Preface

It is now about sixty years since Henry-Russell Hitchcock, Alfred Barr, and I started our quest for a new style of architecture which would, like Gothic or Romanesque in their day, take over the discipline of our art. The resulting exhibition of 1932, “Modern Architecture,” summed up the architecture of the twenties—Mies van der Rohe, Le Corbusier, Gropius, and Oud were the heroes—and prophesied an International Style in architecture to take the place of the romantic “styles” of the previous half century.

With this exhibition, there are no such aims. As interesting to me as it would be to draw parallels to 1932, however delicious it would be to declare again a new style, that is not the case today. Deconstructivist architecture is not a new style. We arrogate to its development none of the messianic fervor of the modem movement, none of the exclusivity of that catholic and Calvinist cause. Deconstructivist architecture represents no movement; it is not a creed. It has no “three rules” of compliance. It is not even “seven architects.”

It is a confluence of a few important architects’ work of the years since 1980 that shows a similar approach with very similar forms as an outcome. It is a concatenation of similar strains from various parts of the world.

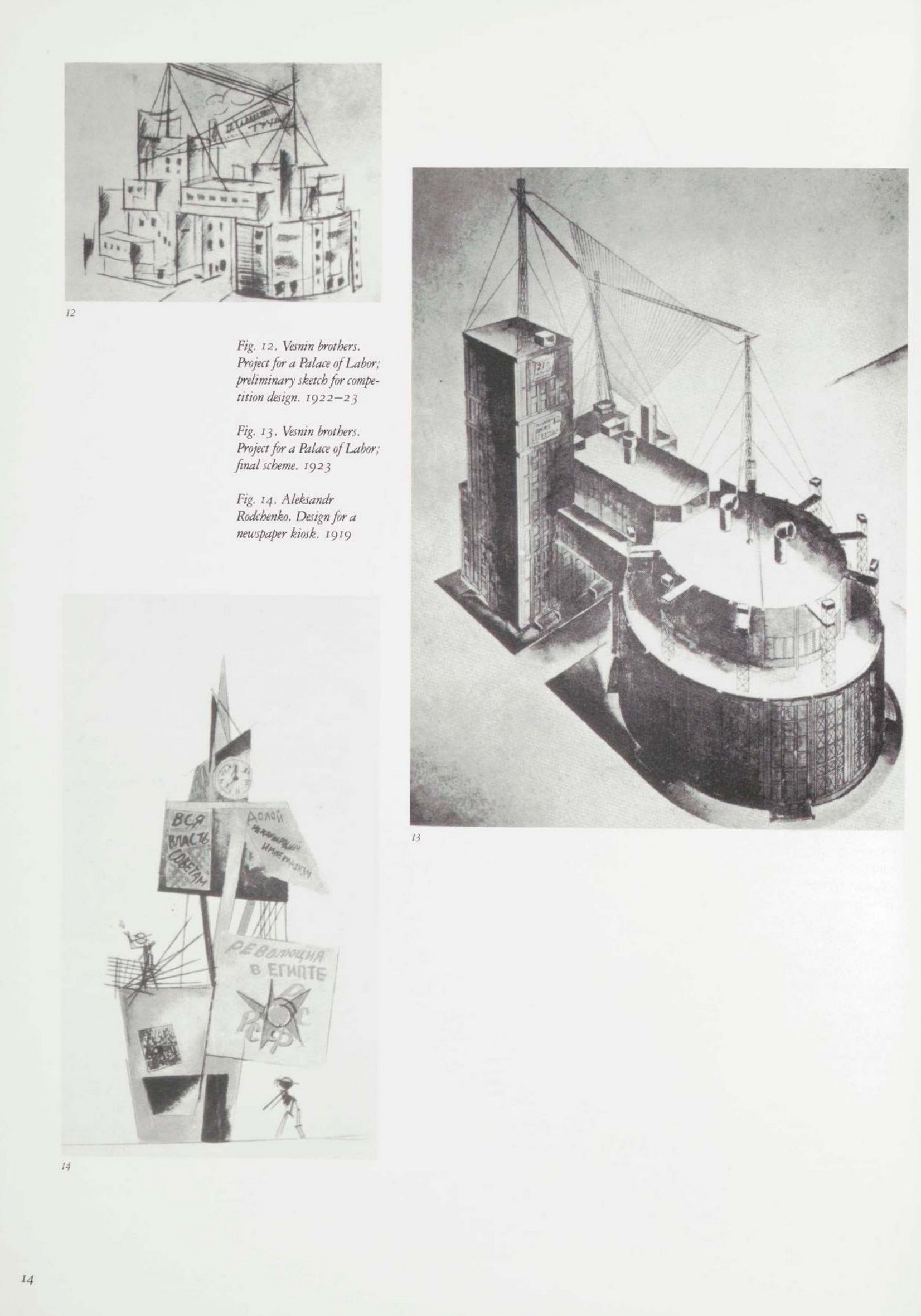

Since no forms come out of nowhere, but are inevitably related to previous forms, it is perhaps not strange that the new forms of deconstructivist architecture hark back to Russian Constructivism of the second and third decades of this century. I am fascinated by these formal similarities, of our architects to each other, on the one hand, and to the Russian movement on the other. Some of these similarities are unknown to the younger architects themselves, let alone premeditated.

Take the most obvious formal theme repeated by every one of the artists: the diagonal overlapping of rectangular or trapezoidal bars. These are also quite clear in the work of all of the Russian avant-garde from Malevich to Lissitzky. The similarity, for example, of Tatlin’s warped planes and Hadid’s is obvious. The “lini-ism” of Rodchenko comes out in Coop Himmelblau and Gehry, and so on.

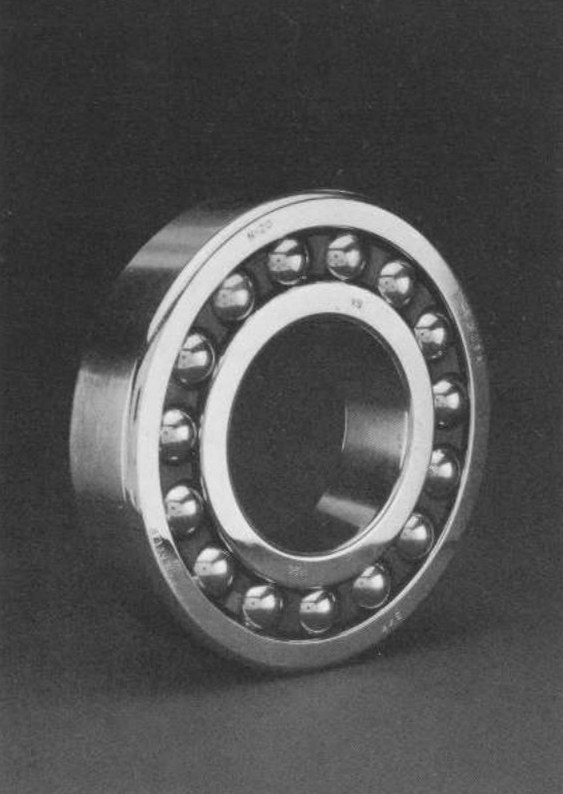

The changes that shock the eye of an old modernist like myself are the contrasts between the “warped” images of deconstmctivist architecture and the “pure” images of the old International Style. Two favorite icons of mine come to mind: a ball bearing, featured on the cover of the catalogue of The Museum of Modern Art’s “Machine Art” exhibition, in 1934, and a photograph taken recently by Michael Heizer of an 1860s spring house on his property in the Nevada desert.

Both icons were “designed” by anonymous persons for purely non-aesthetic aims. Both seem significantly beautifial in their respective eras. The first image fitted our thirties ideals of machine beauty of form, unadulterated by “artistic” designers. The photo of the spring house strikes the same chord in the brain today as the ball bearing did two generations ago. It is my receiving eye that has changed.

Think of the contrasts. The ball bearing form represents clarity, perfection; it is single, clear, platonic, severe. The image of the spring house is disquieting, dislocated, mysterious. The sphere is pure; the jagged planks make up a deformed space. The contrast is between perfection and violated perfection.

Spring house, Nevada. 1860s

The same phenomenon as in architecture is happening in painting and sculpture. Many artists who do not copy from one another, who are obviously aware of Russian Constructivism, make shapes akin to deconstructivist architectural forms. The intersecting “cones and pillars” of Frank Stella, the trapezoidal earth lines of Michael Heizer, and the sliced, warped volumes of a Ken Price cup come to mind.

In art as well as architecture, however, there are many—and contradictory—trends in our quick-change generation. In architecture, strict-classicism, strict-modernism, and all sorts of shades in between, are equally valid. No generally persuasive “-ism” has appeared. It may be none will arise unless there is a worldwide, new religion or set of beliefs out of which an aesthetic could be formed.

Meanwhile pluralism reigns, perhaps a soil in which poetic, original artists can develop.

The seven architects represented in the exhibition, born in seven different countries and working in five different countries today, were not chosen as the sole originators or the only examples of deconstructivist architecture. Many good designs were necessarily passed over in making this selection from what is still an ever-growing phenomenon. But these seven architects seemed to us a fair cross-section of a broad group. The confluence may indeed be temporary; but its reality, its vitality, its originality can hardly be denied.

The person responsible for bringing this exhibition into existence is the Director of the Department of Architecture and Design, Stuart Wrede. He generously invited me to be guest curator of the exhibition and since then has been an authoritative and caring leader, sacrificing time from his own tight schedule to devote energy and direction to ours.

There could have been no exhibition or book without the contribution of my associate, Mark Wigley of Princeton University, theorist, architect, and teacher. In every field, from concept to installation, his judgment, knowledge, and hard work have been paramount.

Assisting myself and him has been Frederieke Taylor, coordinator of the exhibition. Her tireless work, tactfulness, and patient loyalty to the project were irreplaceable.

To Debbie Taylor, my gratitude for her dedication and organizational efficiency; also to John Burgee and his staff for helpful criticism and support.

At the Museum I owe thanks to my co-workers on the publication staff: most especially the editor, James Leggio; also Bill Edwards, Tim McDonough, and Susan Schoenfeld; and the designer, Jim Wageman. In addition, the following individuals contributed to the realization of the exhibition: Jerome Neuner, Production Manager, Exhibition Program; Richard L. Palmer, Coordinator of Exhibitions; James S. Snyder, Deputy Director for Planning and Program Support; Sue B. Dorn, Deputy Director for Development and Public Affairs; Lynne Addison, Associate Registrar; Jeanne Collins, Director of Public Information; and Priscilla Barker, Director of Special Events.

My thanks also to William Rubin, Director of Painting and Sculpture; John Elderfield, Director of Drawings; Riva Castleman, Director of Prints and Illustrated Books; and John Szarkowski, Director of Photography, who so generously lent paintings, drawings, prints, and photographs from the Museum’s collection of Constructivist art. Magdalena Dabrowski, Assistant Curator in the Department of Drawings, was especially helpful with our research of the Constructivist work.

We also thank the following institutions, which so kindly lent works from their collections: the Museum für angewandte Kunst, Vienna; the Senator für Bau- und Wohnungswesen, I.B.A. Archive, Berlin; and Land Hessen, represented by the Staatsbauamt, Frankfurt am Main. Coop Himmelblau wishes to express their gratitude to EWE Küchen, Wels, Austria, for financial assistance in transporting their project models. Lastly, on behalf of Peter Eisenman and Daniel Libeskind, we wish to thank the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Federal Republic of Germany for underwriting the transportation of their models from Frankfurt and Berlin, and we thank Richard Zeisler for assisting us in enlisting the Ministry’s support.

For the impetus to undertake this exhibition I must thank two men who are working on books related to our theme. First there is Aaron Betsky, who called my attention to the telling phrase "violated perfection"—originating from the title of an exhibition proposed by the team of Paul Florian and Stephen Wierzbowski for the University of Illinois, Chicago. The second man is Joseph Giovannini, who was another valuable source of preliminary information on the subject.

Special acknowledgment must go to Alvin Boyarsky and the Architectural Association of London, who acted as the key patron of most of the seven architects in their formative years. The A.A. has been the fertile soil from which many a new idea in architecture has sprouted.

I must thank the artists whose visions have moved me more even than any purely architectural drawings: Frank Stella, Michael Heizer, Ken Price, and Frank Gehry.

In the end, of course, the chief credit must be given to the seven architects and their teams, who not only produced the work, but prepared new drawings and models specially for the exhibition.

Philip Johnson

Curator of the Exhibition

Contents

Foreword. Stuart Wrede 6

Preface. Philip Johnson 7

Deconstructivist Architecture. Mark Wigley 10

Projects. Commentaries by Mark Wigley

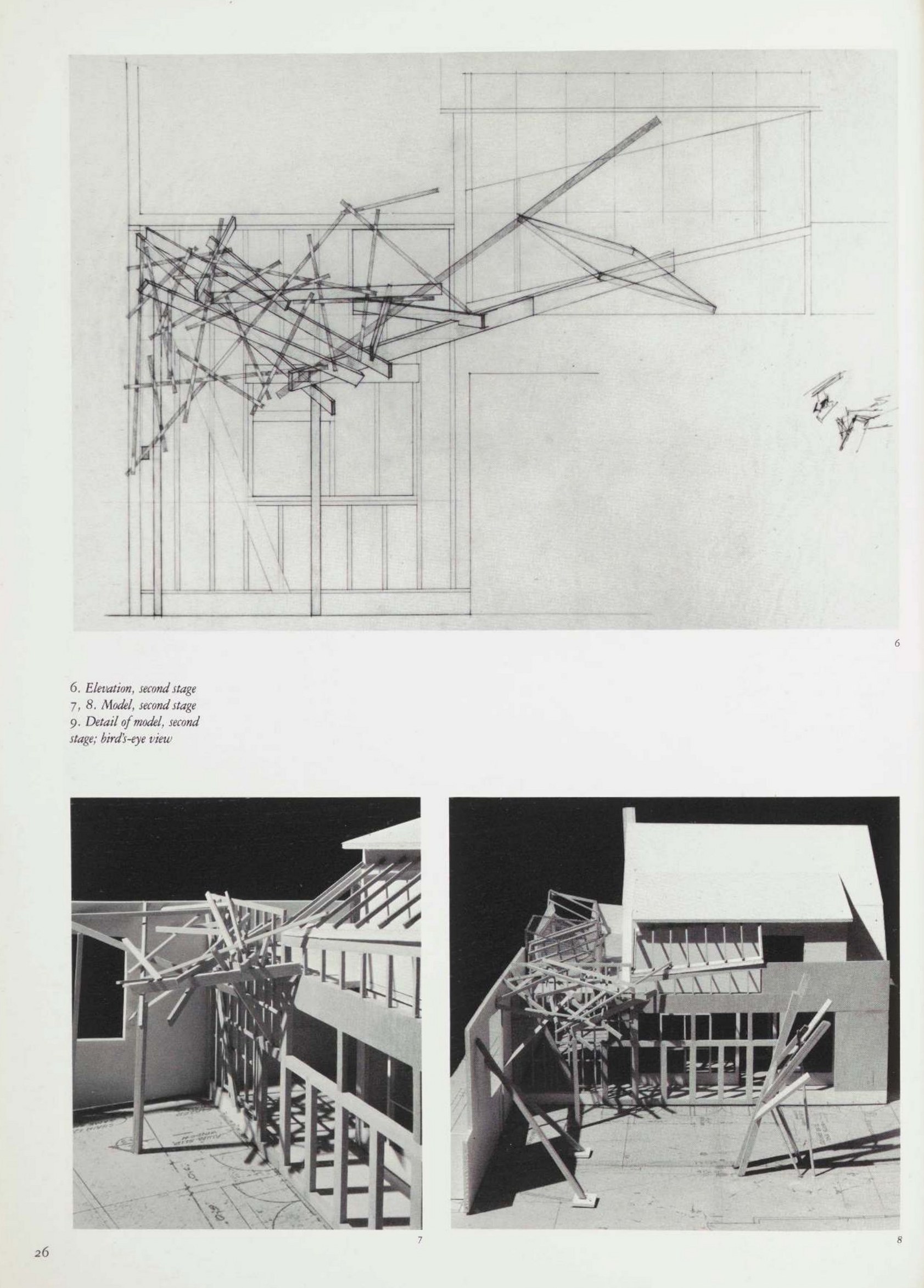

Frank O. Gehry 22

Daniel Libeskind 34

Rem Koolhaas 46

Peter Eisenman 56

Zaha M. Hadid 68

Coop Himmelblau 80

Bernard Tschumi 92

Sample pages

Download link (pdf, yandexdisk; 19,5 MB).

Source: moma.org

4 ноября 2018, 20:24

0 комментариев

|

Партнёры

|