|

|

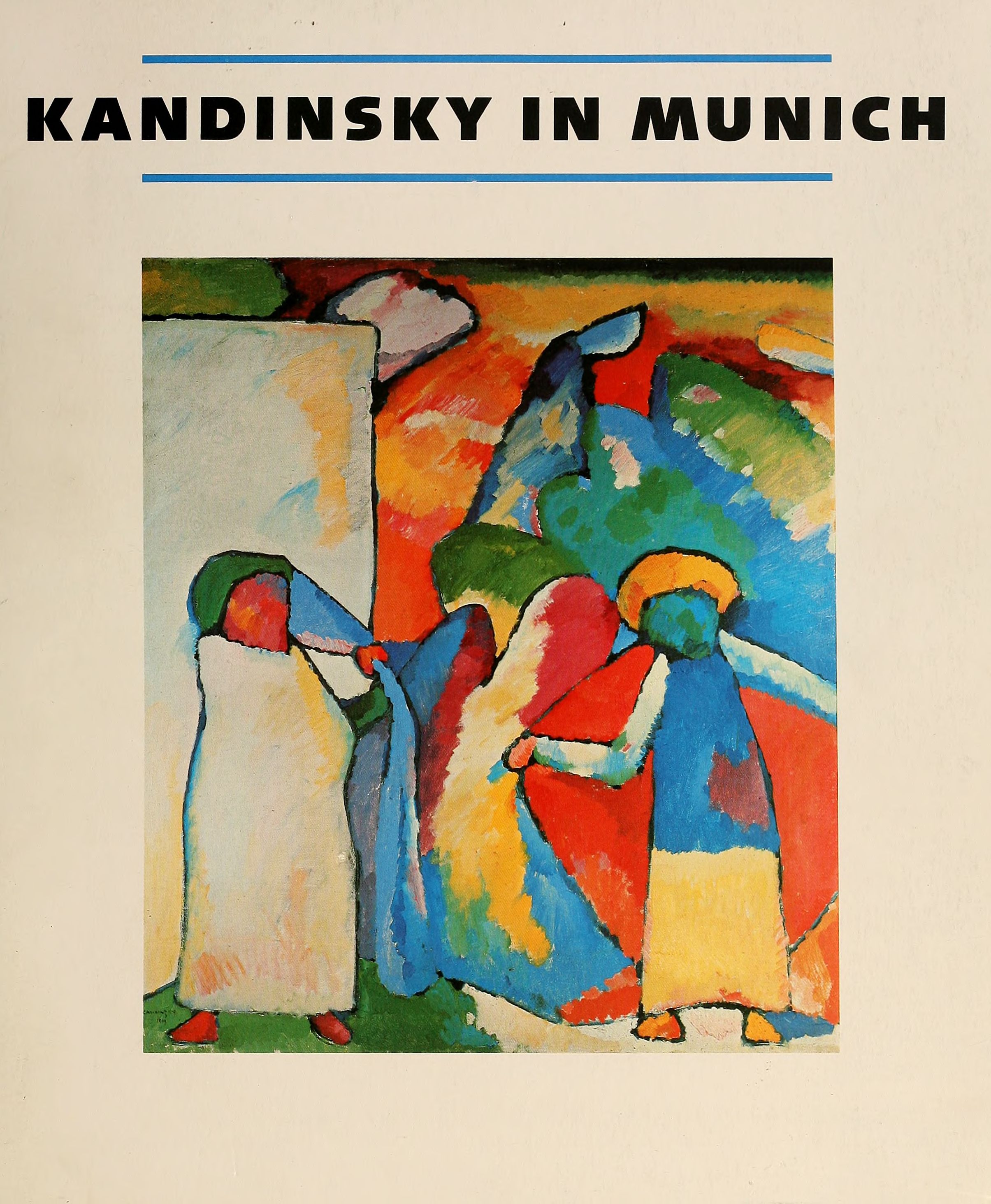

Kandinsky in Munich: 1896—1914. — New York, 1982Kandinsky in Munich: 1896—1914 : Catalogue of the exhibition. — New York : The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 1982. — 312 p., ill. — ISBN 0-89207-030-7PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Vasily Kandinsky, it may be stated fairly, lived at least three lives in one. In the course of his seventy-eight years, despite an exceptionally late start as an artist, his work encompassed three stylistic phases which, though ultimately comprehensible as a unity, nevertheless are more than ordinarily separable from one another. Each of these—in Munich before World War I; at the Bauhaus during the postwar years; and in Paris from the rise of Nazism through World War II—represented a major episode which was more or less self-contained. In each Kandinsky developed a style that corresponded to a particular insight, and each reflected an advanced, visionary sensibility.

Various retrospectives at the Guggenheim and at many other museums around the world have rendered visible, through chronological presentation of his work, the stages of Kandinsky’s stylistic development, thereby providing the necessary background which is a precondition for a more detailed, analytical investigation of his oeuvre. This probing and extensive investigation is now being attempted in a sequence of three exhibitions beginning with Kandinsky in Munich and projected to take place over a period to last beyond the first half of this decade.

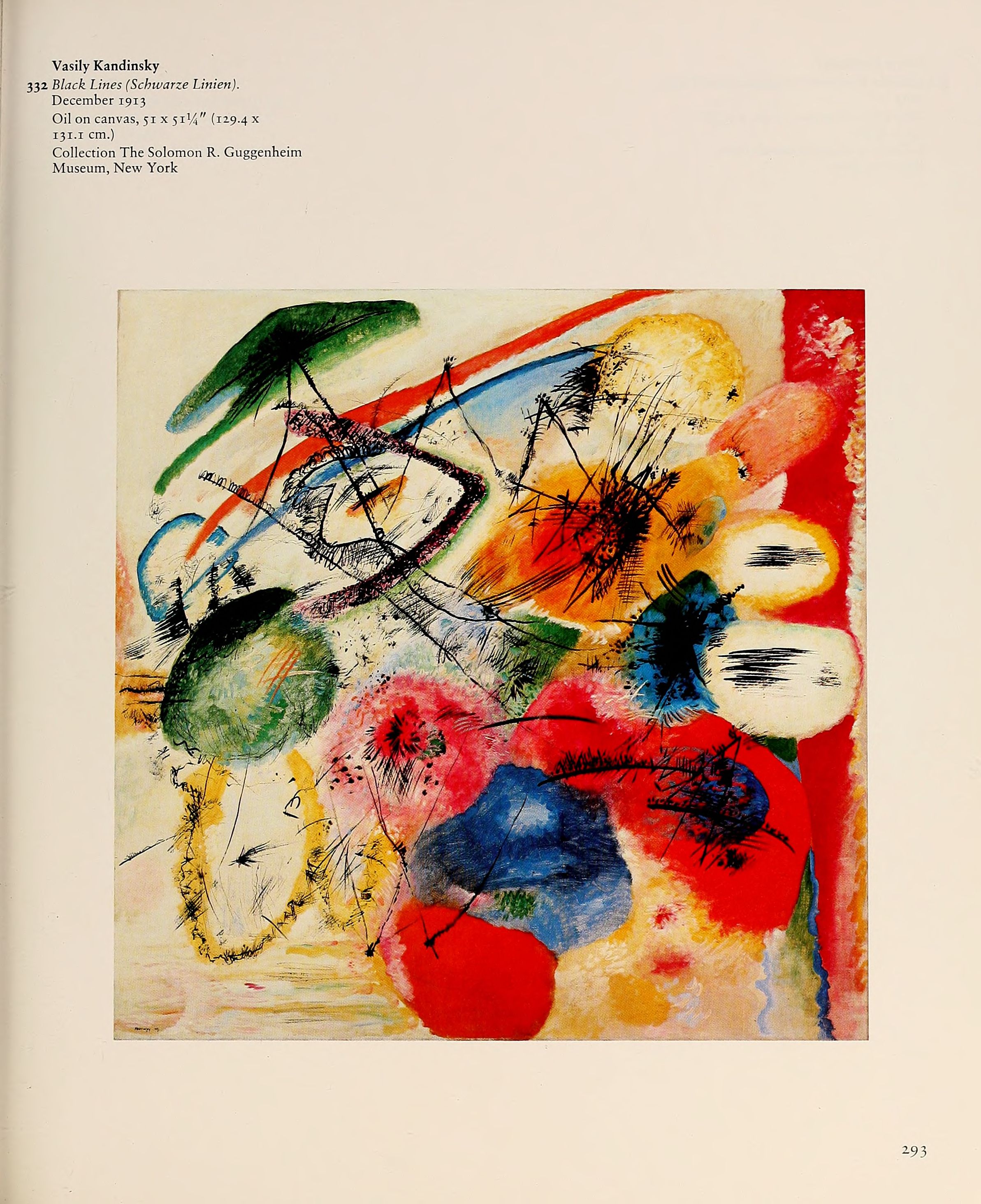

It is of course not by happenstance that so ambitious and demanding an undertaking concerning Kandinsky’s art should have taken shape at the Guggenheim Museum; for if institutions may lay claim to patron saints and may be said to issue from and be propelled by single identifiable impulses, mitigating influence of stylistic crosscurrents notwithstanding, Kandinsky and the Guggenheim exemplify such an interrelationship. In this context it is sufficient to recall that the Guggenheim Museum’s original name, which it bore from its creation in 1937 until 1952, was the Museum of Non-Objective Painting and that among the artists who provided the basis for a designation derived from this stylistic attribute, Kandinsky was preeminent. Throughout the decades succeeding its initial phase, the Museum’s focus upon Kandinsky has continued, so that the concentration of his works in the collection and the frequency of their exhibition surpasses that of all other artists.

But it is obviously not merely because of the large quantity of Kandinsky’s works in our holdings that such an emphasis could have been established and sustained; rather it is Kandinsky’s enduring relevance to thought and art in our era that has justified the frequent and prominent exposure of his oeuvre and has invited constant reevaluation of its meaning. It is, in fact, at a moment when the connotations of “abstraction” are changing quite radically that we have approached Dr. Peg Weiss, Adjunct Professor at Syracuse University, New York, and author of the recent volume Kandinsky in Munich: The Formative Jugendstil Years, to act as guest curator and make the selection for an exhibition similar in title and concept to that of her book. At the same time we have asked Ian Strasfogel, former Director of the Washington Opera at Kennedy Center, Washington, D.C., to produce Kandinsky’s opera The Yellow Sound (Der gelbe Klang).

The two related, simultaneously scheduled enterprises demarcate the sizeable scope of our Kandinsky projects, particularly in the context of the future exhibitions in the series. Both call for capabilities beyond those normally at our disposal—the exhibition, because its documentary emphasis requires the installation of a great many heterogeneous objects; Der gelbe Klang, because of the problems inherent in the production of an unfinished musical score, as well as the many circumstances, unfamiliar to us, associated with theatrical presentations in general. Dr. Weiss and Mr. Strasfogel, therefore, depended upon expert help on many levels. Thus Gunther Schuller undertook to arrange Thomas de Hartmann’s incomplete score and Hellmut Fricke-Gottschild assumed responsibility for the choreography of the opera. Two teams of designers, Robert Israel and Richard Riddell for Der gelbe Klang and Charles B. Froom and Richard Franklin for Kandinsky in Munich, fulfilled creative roles in the area of stage design and exhibition installation respectively.

The demands of the project throughout its conception, selection, documentation and staging involved many individuals in addition to the principals, and, therefore, much credit is due to virtually the entire Museum staff —members of its curatorial, technical and public affairs divisions who assured the punctual presentation of exhibition and publication. The Museum’s Research Curator Vivian Barnett coordinated all aspects of the undertaking; she is the primary link between the current Munich-centered phase of our sequence and the two subsequent installments in preparation. Susan Hirschfeld, Exhibitions Coordinator, conscientiously served as the Guggenheim’s liaison with authors and Guest Curator, while Carol Fuerstein edited the catalogue with her usual precision.

The publication as a whole and its principal essay in particular benefitted from Dr. Weiss’s extensive research and the catalogue is further enriched by two essays written for the occasion by Dr. Carl E. Schorske and Peter Jelavich. We are most grateful to these authors for providing conceptual clarifications and for establishing a historical context for the Kandinsky in Munich exhibition.

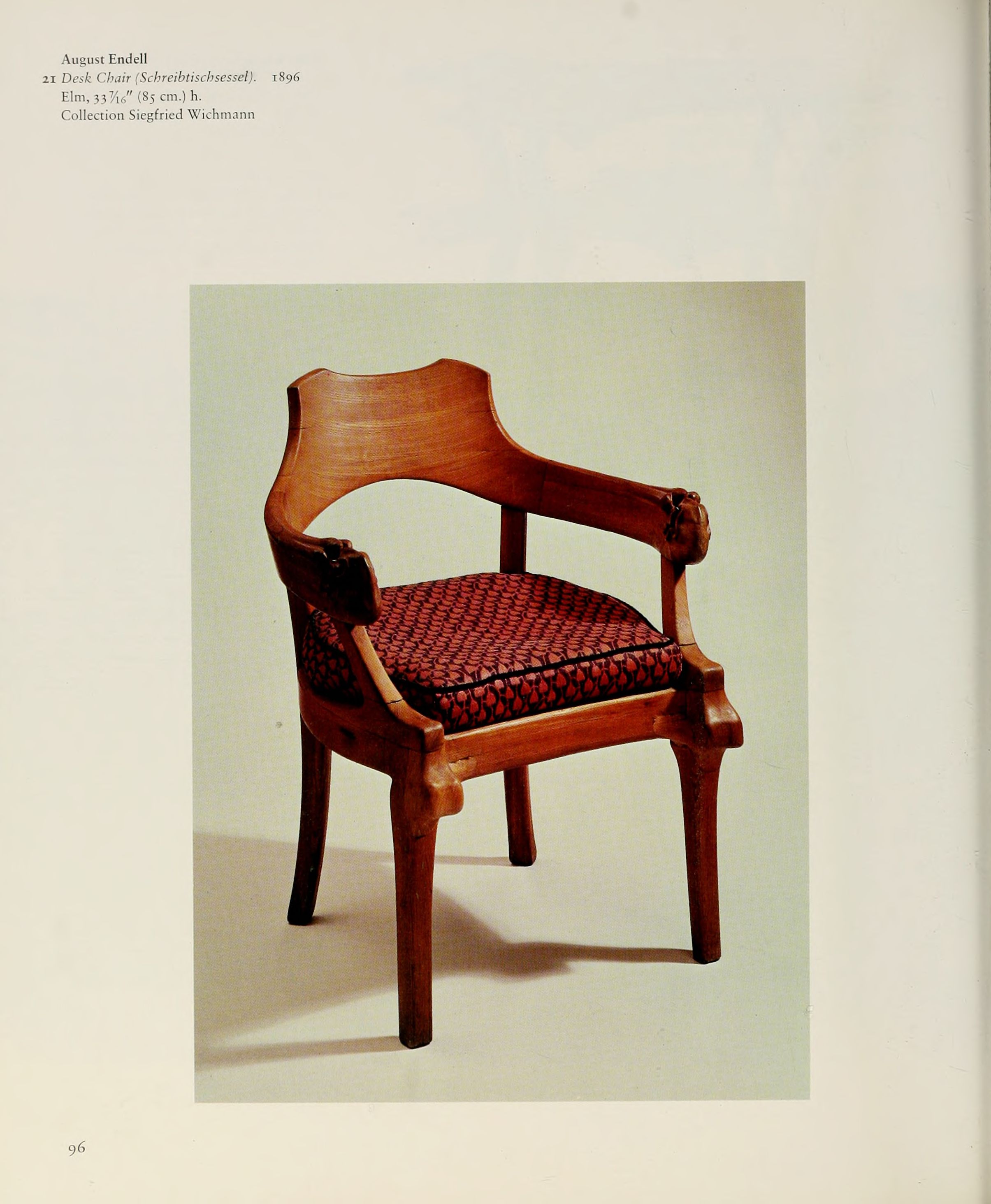

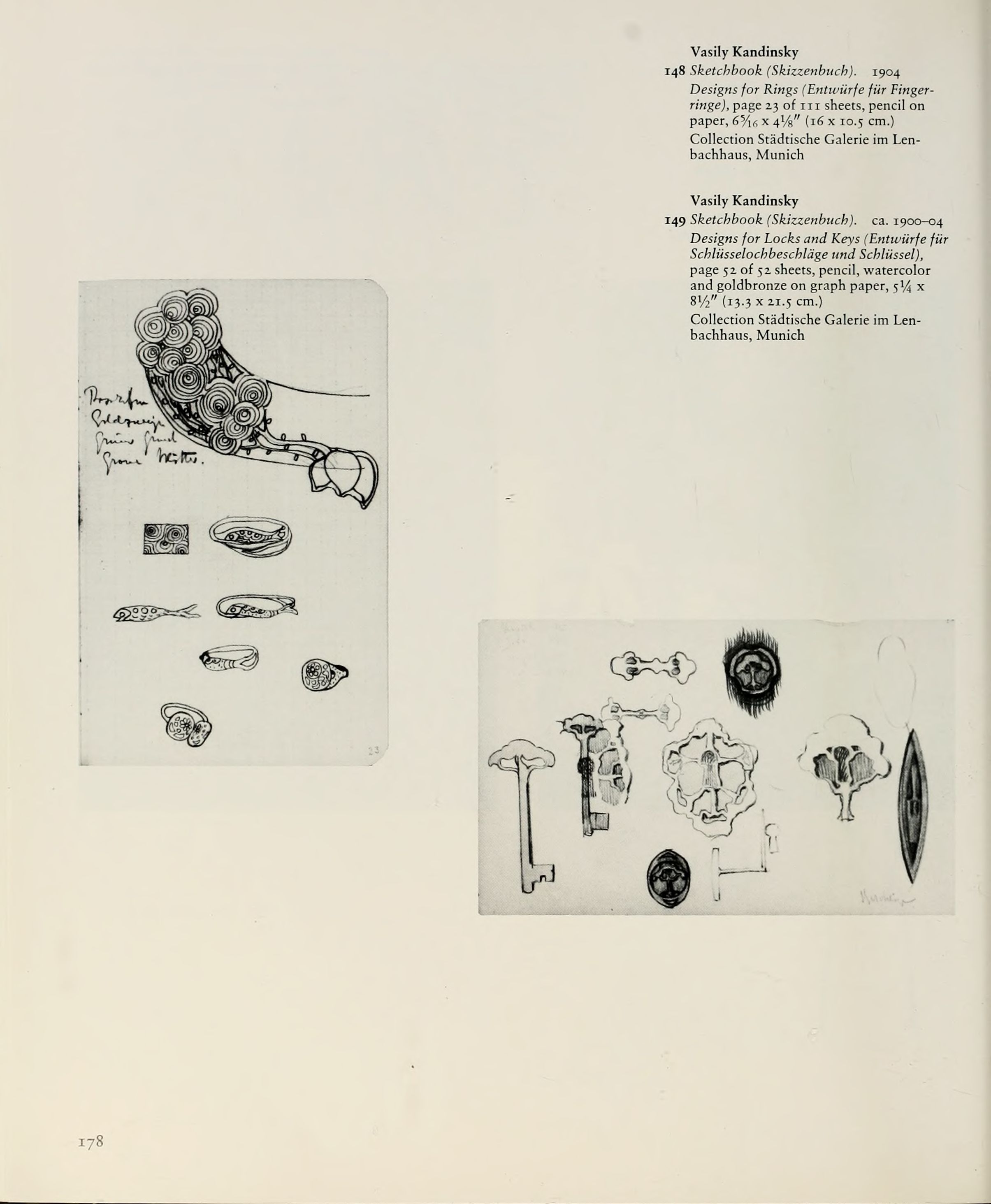

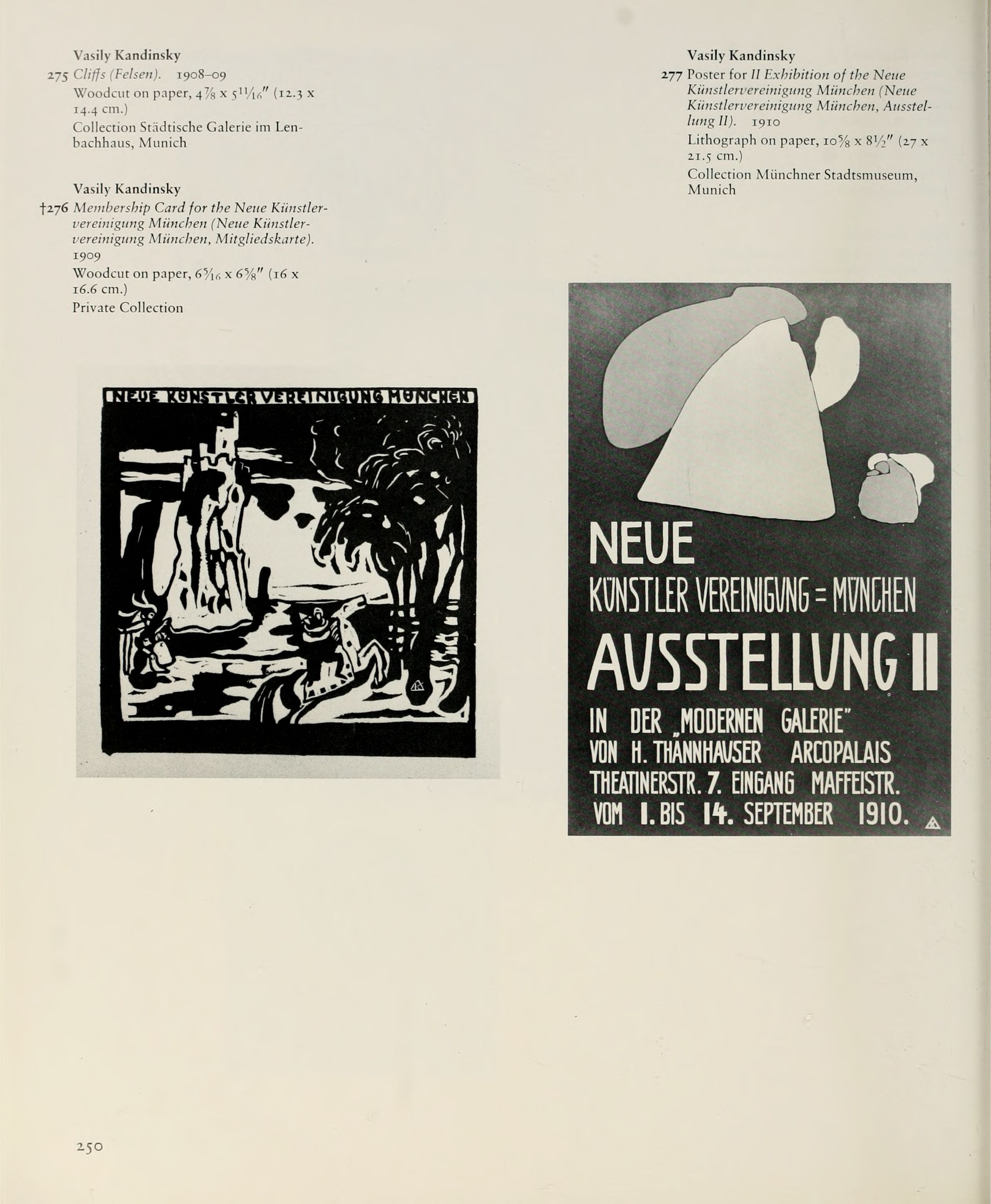

Neither the scholarship brought to bear upon Kandinsky’s art nor the expertise of the technicians charged with the staging of the exhibition would have fully accomplished their objectives had we not also profitted from the extraordinary generosity of the lenders who are listed in a separate section of this catalogue. The need to secure particular works of art in order to make specific stylistic and historical points allowed us to make very few substitutions for our original choices. Our persistence as borrowers increased, therefore, as options for replacements diminished and deeply felt gratitude is due to the many generous owners who responded to our entreaties and allowed us to incorporate their precious objects in the present exhibition. Among the lenders we are indebted to numerous public and private collections in Munich for making many crucial works available to us. Special mention and thanks are extended to the Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus, Munich, for the loan of over one hundred works; in particular, we would like to thank Dr. Armin Zweite, Director, and Dr. Rosel Gollek, Curator, for their efforts on our behalf. We would also like to single out the Münchner Stadtmuseum and Prof. Dr. Siegfried Wichmann for their numerous and invaluable loans. The exhibition has benefited from important works borrowed from the Gabriele Münter-Johannes Eichner Stiftung, Munich. We are grateful to Jean-Claude Groshens, President of Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris, and Christian Derouet of the Musée National d’Art Moderne, Paris, for their assistance regarding works from the Estate of Nina Kandinsky, the artist’s widow.

The demanding nature of this endeavor was, of course, felt in the area of finances. Fortunately, the National Endowment for the Humanities displayed an enlightened interest in the exhibition at an early moment and provided initial funding, enabling us to secure the essential additional resources. Philip Morris Incorporated first matched the initial grant of the National Endowment for the Humanities and subsequently donated the necessary funds for the production of Der gelbe Klang. By so generously affirming their confidence in the Guggenheim’s project, Philip Morris Incorporated and its Chairman George Weissman have once again demonstrated their leading position among the country’s corporate supporters of cultural events. The far-reaching assistance received from the complementary sources of government agency and corporate sector has exemplary value, of course, as well as tangible worth in the present circumstances.

In closing, I should like to thank my colleagues Henry T. Hopkins, Director of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, and Dr. Armin Zweite, Director of the Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus, Munich; much to the benefit of the exhibition, they have participated in the lengthy preparations for the presentation of Kandinsky in Munich: 1896—1914 at the Guggenheim and their own museums.

Thomas M. Messer, Director

The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation

FOREWORDCarl E. Schorske

Kandinsky in Munich: the very title of this exhibition suggests a convergence of a person and a place, an artist and a city. It is a convergence too of two kinds of art exhibit usually held apart. One of these has become almost a dominant form of exhibition in our century: the one-man retrospective, such as the great Picasso show of 1980. This form arose as handmaiden to an important mode of intellectual understanding of art in modern times. Under it, art is viewed as the creation of single developing minds, the achievement of which can best be grasped in the temporal sequence of its products. In the 1970s, however, another form of exhibition kindled the public imagination, one that focuses on the collective artistic production of a single time and place. The Philadelphia Museum’s Art of the Second Empire was one variant of this refreshed historical approach to visual culture. It compelled the viewer to place his present-day conceptions of artistically valid mid-nineteenth century French art (i.e., an aesthetic derived from the Impressionists and Post-Impressionists) into the historical context of the culture that produced it, a culture with quite different canons of critical judgment, wider stylistic content and long-forgotten modes of displaying—and therefore seeing—works of art. Another variant of this new historical approach to art explores and exploits the city as a cultural unit. The Centre Pompidou has developed the city exhibition to new heights, placing the visual arts of Paris in an international perspective by comparison with other urban cultures: Paris-New York, Paris-Berlin, Paris-Moscow. Not only are the plastic arts of France clarified in these exhibitions, but they are illuminated in a context of artistic and intellectual expression in other media, especially literature.

Even as they demonstrate the power of their contrasting perspectives, these two types of exhibition—the individual-textual retrospective and the cultural-contextual or city exhibition—have dwelt far apart and ignored each other’s virtues. The concentration on the single painter’s oeuvre has tended to detach it from its social and cultural environment. The concentration on a cultural context, on the other hand, has tended to blur the vision of the special, often isolated values of the individual artist’s product. Thus we confront, on the one side, text without context; on the other, context without text.

Behind this polarization in exhibiting practice lies a division of view that developed over the last century concerning the nature and function of art and its place in society. As painting ceased to be produced primarily on commission to embellish a church, a public building or a residence, the artist won independence from traditional value systems. It was an ambiguous freedom, combining imaginative opportunity with cultural rootlessness. On the one hand, the artist became free to devise his own code of meanings, to project his individual vision onto his canvas, independent of any ultimate social use or destination. On the other hand, he became dependent on a public art market to find an anonymous patron who might share his personal vision. France set the tone for nineteenth-century Europe in organizing the art market in the form of the “salon,” where the artists adjudged qualified might display their wares collectively for the perusal of potential buyers. The salon was a form of exhibition appropriate to the era of democracy and economic laissez-faire, where the individualistic artist-producer and the connoisseur-consumer could find each other as seller and buyer. Although traditional criteria of judgment of aesthetic worth still exercised a restraining influence on what works the salon accepted for display, two important new principles of modern culture surfaced in the salon in uneasy interaction: “art for art’s sake” and “business is business.”

It was only logical that the artist who produced no longer on commission but out of his own powers should separate himself from the values, both in subject matter and in form, traditionally assigned to painting by society. But he could do this in two different ways, one individual, the other, social. The “modern” artist who followed the more individual course formulated new and highly personal pictures of the world, devising his own visual language for the purpose. To the degree that his sense of individuation estranged him from society, his art became less concerned with representation of the world of nature and inherited culture than with the presentation of a personal vision, sometimes of his own feeling, sometimes of the shaping or abstracting powers of art itself.

The retrospective exhibition of a single artist arose as a logical reflection in display practice of this process of artistic individuation, the process by which the very life of art became the expression of a personal vision rather than a shared cultural one. For such an artist as Vasily Kandinsky, who embodied in his own development the passage from “representation” to “presentation,” from realism to abstraction, the temporal array of his oeuvre seems a particularly suitable form of exhibition.

But is it enough? To answer the question, one must turn to the other strand of artistic thought and practice that arose in response to the emergence of the autonomy of art in the nineteenth-century world of commerce: the social strand. In Europe’s intellectual community there were those who could not accept the separation of the artist from the moral and social functions that by tradition had been his. They criticized the artist from a social point of view while they castigated the society from an aesthetic point of view. Above all, they sought to engage the artist in the task of regenerating society and, in the process, of closing the gap that had opened between culture and society, between art and public life.

Where France led the way in the development of a pluralized and individuated modern art, England and Germany pioneered in the creation of an art endowed with redemptive social functions. In England, under the inspiration of John Ruskin and the leadership of William Morris, the Arts and Crafts Movement mobilized the arts to restore beauty to the daily life of an England made ugly by industrialism and socially irresponsible by capitalism. The movement aimed to reunite the imagination of the artist with the skill of the artisan, thus to reinvest the use-objects of the common life—from houses and furniture to printed books and pots and pans—with the simplicity and elegance of medieval design. The painter became a decorator of surfaces—of walls or three-dimensional use-objects—with a resulting tendency to replace three-dimensional perspective with flat, two-dimensional forms and unnuanced color juxtapositions. Both in style and in idea, art was transformed by its purposive application to the world of utility to redeem it with beauty.

While the English medievalizing avant-garde moved toward transforming the outer environment through the applied arts, the Germans, under the vigorous leadership of Richard Wagner, sought to fight the materialism of the age through a different medium: the theater. Exalting in classic German fashion the example of ancient Greece, Wagner sought to create a theater which would perform for his age two functions at once: to restore the broken unity of the arts by bringing all the arts together in music drama; and to provide hyper-individuated and divided modern society with a model of community. “Art for art’s sake” and “business is business” would both be overcome by means of a theater critical of the anomic present and formative of a communitarian future.

Morris and Wagner, both anti-capitalist, both extolling medieval crafts and medieval poetry, both espousing political radicalism, radiated their respective forms of redemption—the one plastic and visual, the other musical and theatrical—throughout Europe. In Munich, the two movements met. Here it was that young Kandinsky encountered both in their fin-de-siècle incarnations.

How ironically fitting it was that the counter-cultures launched by Morris and Wagner should meet in Munich as the nineteenth century neared its end! For Munich had become the major Central European center of art on the official French model, with a vigorous, dominant, traditional academy and a salon that ranked as the outstanding display and exchange center for painting east of the Rhine.

Kandinsky came to Munich to study painting in the French-inspired academic tradition, and the autonomous canvas remained the principal vehicle for his ultimate, highly personal vision. But to understand the ideational content and increasingly atomized and condensed visual form of his work, one must see his Munich experience whole, with the powerful countercurrents which swept him up—of arts and crafts, of socially critical theater, of artistic synaesthesia—that in their separate ways challenged the autonomist aesthetic of painting. Accordingly, Kandinsky in Munich combines the genre of a retrospective exhibition with that of a collective city-culture, for only thus can his oeuvre emerge as both individual creation and historical condenser.

This catalogue is designed to open for the viewer/reader the multiple dimensions of the exhibition. Accordingly, two professional disciplines are represented in it. Peg Weiss who, as guest curator, has conceived and mounted the exhibition, is an art historian. In the principal essay in the catalogue, Dr. Weiss analyzes Kandinsky’s development in terms of the varied cultural movements—decorative, folkish, theatrical, poetic—showing how the painter ingested them in thought and projected them as vision in his works. A social historian of culture, Peter Jelavich, provides a wider background. Bringing into conjunction the rich if contradictory legacy of Munich as cosmopolitan art-capital of Central Europe, he illuminates the crises in both politics and culture that opened new problems and new possibilities for art and for the function of the artist in the first decade of our century.

To appreciate so powerful an artist as Kandinsky, so sensitive a respondent to the contradictory pressures of Munich’s vital cultural environment, one needs more than the texts that are his works. Conversely, to appreciate historically the full affective and intellectual reality that was Munich culture before 1914, one needs the formed feeling that only a great artist can provide. Kandinsky in Munich, therefore, aims to join together the aesthetic and historical modes of understanding and of exhibiting, to present text and context, the artist’s work and his cultural environment, in reciprocal illumination.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

8 Sponsor’s Statement

9 Preface and Acknowledgements. Thomas M. Messer

13 Foreword. Carl E. Schorske

17 Munich as Cultural Center: Politics and the Arts. Peter Jelavich

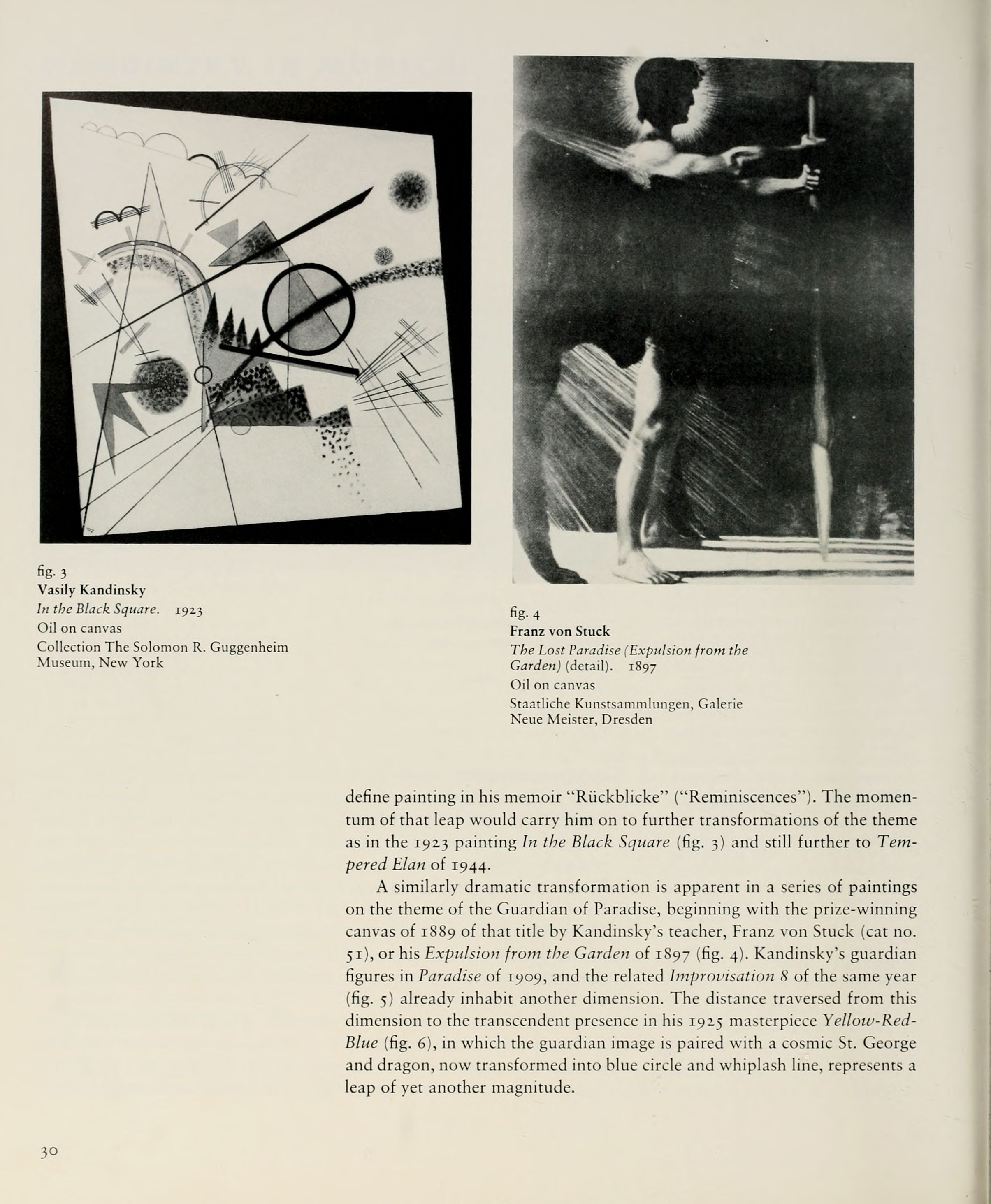

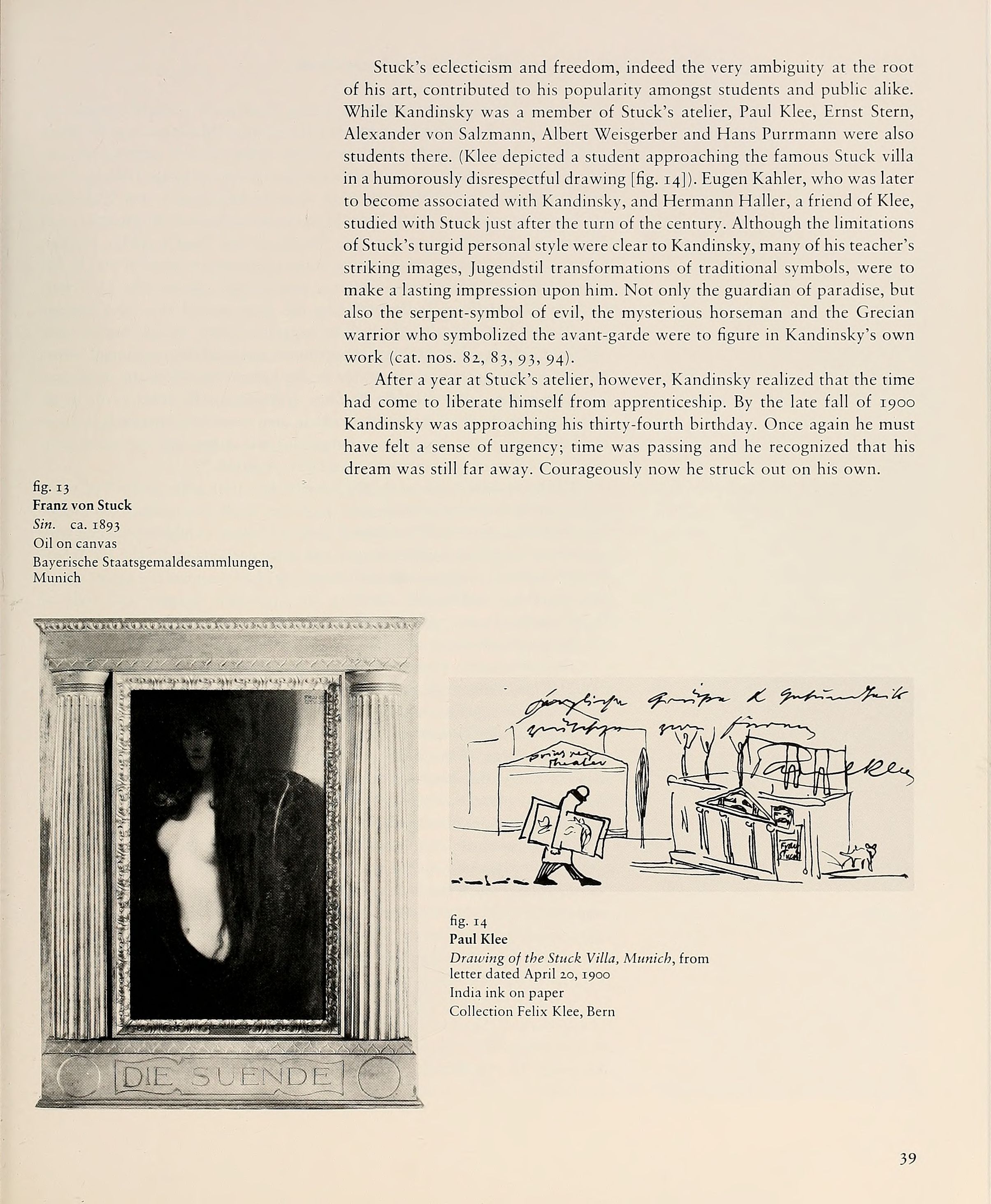

28 Kandinsky in Munich: Encounters and Transformations. Peg Weiss

83 Catalogue

303 Chronology. Peg Weiss

307 Selected Bibliography. Peg Weiss

310 Index of Artists in the Catalogue

311 Photographic Credits

Sample pages

Download link (pdf, yandexdisk; 109 MB).

8 мая 2018, 18:03

0 комментариев

|

Партнёры

|

Комментарии

Добавить комментарий