|

|

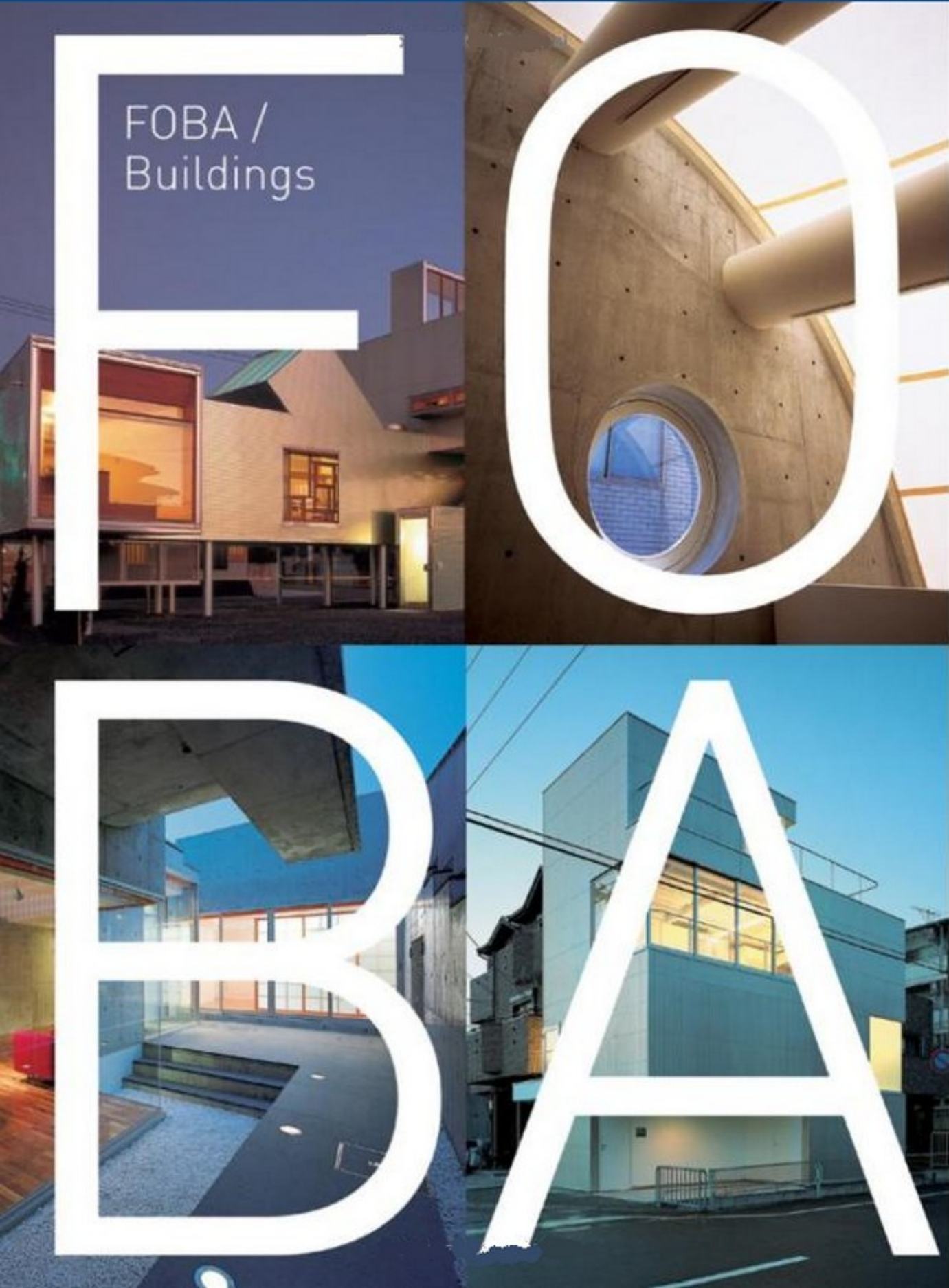

Katsu Umebayashi, Thomas Daniell, Michael Webb, Peter Allison, Kazuhiro Kojima. FOBA : Buildings. — New York, 2005  FOBA : Buildings / Essays by Katsu Umebayashi, Thomas Daniell, Michael Webb, Peter Allison, Kazuhiro Kojima. — New York : Princeton Architectural Press, 2005. — 224 p., ill. — ISBN 1-56898-527-4Table of Contents

Acknowledgments / 6

Nesting: Beyond Objects to the Bodily Experience of Space / 9 Katsu Umebayashi

FOBA: It's Not What It Looks Like / 13

Thomas Daniell

Clarity and Complexity / 17

Michael Webb

Aura / 27

Pleats / 41

Porous / 59

Strata / 73

Skip / 87

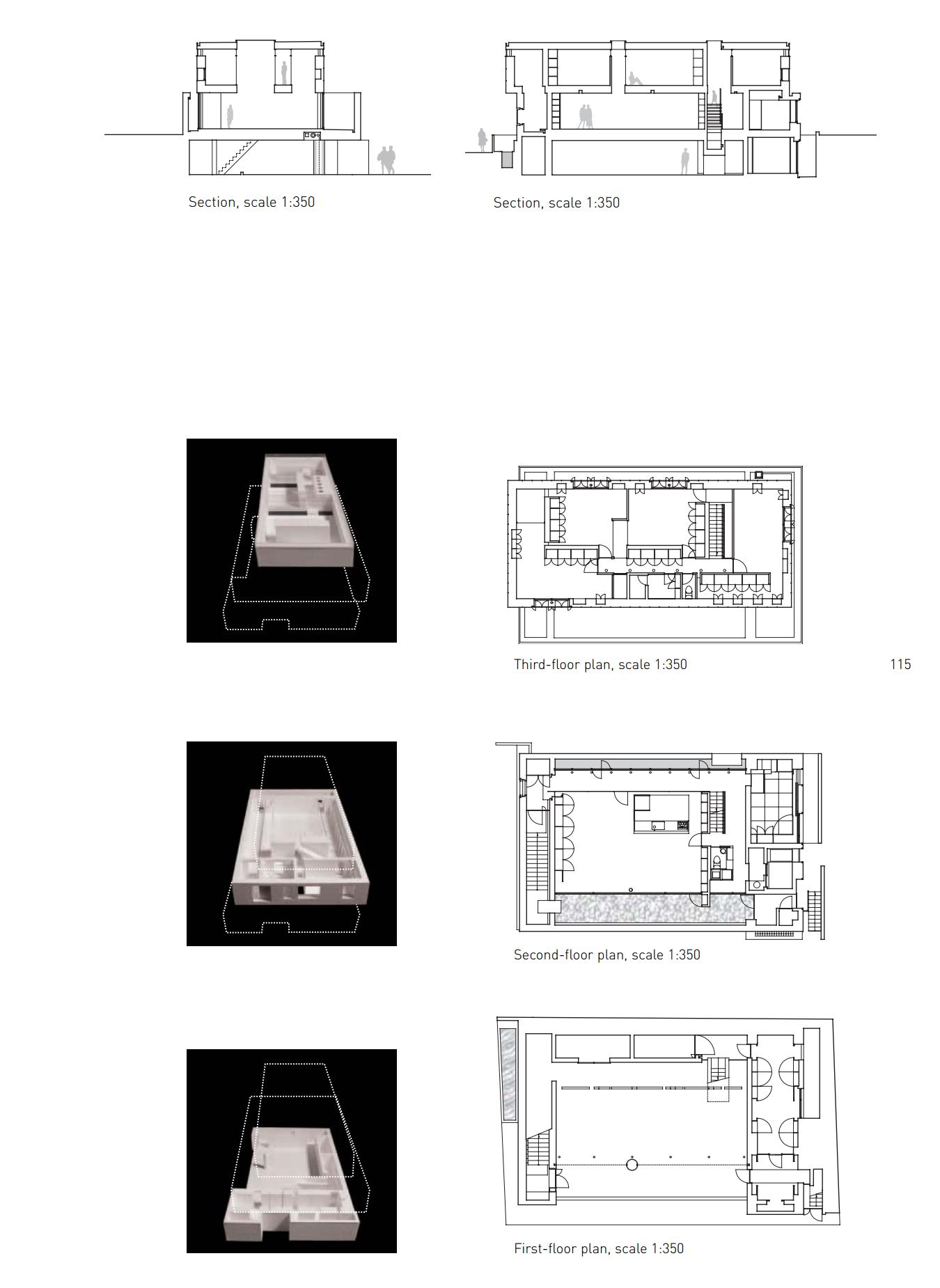

Stack /105

Organ / 119

Myougei /135

Asphodel /145

Orient / 159

FOB Homes: Brand Recognition / 169

Thomas Daniell

FOB Homes Typologies / 172

Prototypes in Suburbia / 177

Peter Allison

FOB Homes Examples /

F-House / 186

H-House / 192

T-House / 196

K-House / 200

I-House / 204

F-Blanc / 208

S-Blanc / 212

Afterword / 219

Kazuhiro Kojima

Selected Bibliography / 222

Author Biographies and Credits / 224

Nesting: Beyond Objects to the Bodily Experience of Space /Katsu Umebayashi

Although the Japan in which I live can no longer be described as an economic superpower, the rest of the world may view the majority of the population here as enviably wealthy. Yet many of us here feel that the spaces of our daily lives are somehow impoverished. Why should that be so? It seems that the origin of this poverty lies partly in our architecture. With the motivation of simply trying to address this issue, I have devoted the last decade to designing small buildings.

Of course, phrasing it in that way makes it seem as though focusing on small buildings was a deliberate choice. In fact, it is because most of the design opportunities available to young Japanese architects are within the vast quantities of tiny, fully detached houses that are constantly being built all across the country. Yet despite the familiarity and banality of these structures, I consider them to be intimately related to a variety of social problems, such as juvenile delinquency and social alienation. Small buildings possess the latent power to jolt our conventional conceptions about architecture.

Japan's chronic shortage of buildable terrain has resulted in a deeply entrenched "myth of land"—the illusion that real estate is an eternal asset. In the period following the Second World War, the Japanese public became such devoted disciples of American-style democracy that possessing one's own plot of land became a fundamental aspect of the government's social policies.

Looking at the built results, it is clear that the desire of the average person for their own private house is so widespread that it has become even more prevalent than among our American role models. From farm village to metropolis, the entire nation has been swamped with endless arrays of fully detached houses. The impact of these small buildings cannot be ignored. The cumulative effect of their multiplication has been to shatter our sense of authentic place. The natural beauty of Japan is now just a poignant memory, blanketed by scenes of capitalist development. At a conceptual level, this is a result of our perception of wealth having been reduced to nothing more than the ownership of things. From the period of Japan's intense economic growth during the 1960s until the collapse of the so-called "bubble economy" in the early 1990s, the clearest indicator of personal economic success was to ostentatiously fill your home with consumer goods. We are only now coming to realize that we have been progressively obscuring the true wealth of our cultural history and natural environment. The apparent wealth of conspicuous consumption only disguises our actual poverty.

Can we invent methods that allow us to escape this systematic impoverishment? It has become a pervasive phenomenon that extends beyond the field of architecture, afflicting every aspect of our lives. Although we may be in control of the processes that produce this phenomenon, our techniques are ineffectual in any situation other than the currently existing one—much like the way the theories and methods of Newtonian physics, Marxist economics, or Darwinian biology are only valid within circumscribed domains. Although the impact of this impoverishment is becoming increasingly clear, it remains insufficiently exposed and theorized.

Our sense of place is relentlessly eroded by the onslaught of information, by communication technologies, and by the volatility of contemporary society. In the field of architecture, we have abandoned our sensitivity to the specificity of place in favor of the neutral freedom promised by Miesian "universal space." Our former harmoniously integrated sense of place has been regimented and fragmented by modernist rationality; the notion of place no longer refers to a permanent location but to an arbitrary and changeable address. With our sense of place now partitioned to the point where it may be seen as an endless array of objects, these deterritorialized objects contain the potential to be reassembled into unprecedented configurations, resulting in new types of place. The creation of modernist universal space relies on a clear distinction between place and object, but in the real world their respective identities have become ambiguous—place is just another commodity to be owned or exchanged. Universal space is therefore now something that can only be produced in a test tube, not in the real world.

How should we build in a world of such total relativity, where places have become objects? Taking a more positive view of this situation, if everything is now relative, we may make design choices with absolute freedom. By treating all phenomena—time, place, history—as equivalent, they may be juxtaposed, superimposed, and blended at will.

Transcending modernist rationality, this new type of place may be assembled at any arbitrary location and is predicated on our ability to freely select materials from the environment, like a bird assembling a nest. Such a nonhierarchical nest of found objects is a phenomenological mirror that reflects its surroundings. Making a nest is a process of accumulating objects, producing ambiguous boundaries that never result in completely isolated spaces. Here, then, is a new way for architecture to attain a sense of wealth.

Sample pages

Download link (pdf, yandexdisk; 14.8 MB)

The electronic version of this edition is published only for scientific, educational or cultural purposes under the terms of fair use. Any commercial use is prohibited. If you have any claims about copyright, please send a letter to 42@tehne.com.

24 августа 2024, 13:08

0 комментариев

|

Партнёры

|

Комментарии

Добавить комментарий