|

|

Louis I. Kahn: In the Realm of Architecture. — New York ; Los Angeles, 1991  Louis I. Kahn: In the Realm of Architecture / David B. Brownlee, David G. De Long ; Introduction by Vincent Scully ; New photography by Grant Mudford. — New York : Rizzoli International Publications ; Los Angeles : The Museum of Contemporary Art, 1991. — 448 p., ill. — ISBN 0-8478-1323-1 (HC) ; ISBN 0-8478-1330-4 (PBK)

Louis l. Kahn: In the Realm of Architecture is the first comprehensive documentation and analysis of the complete architectural oeuvre of Louis I. Kahn, one of this century's greatest architects and teachers.

Although revered and studied for years, Kahn’s work and his philosophy of architecture have never before been thoroughly examined in one volume. The book’s primary texts critically address different dimensions and periods of Kahn’s architecture. They are followed by a 160-page color portfolio of illustrations—consisting primarily of newly commissioned photographs by Grant Mudford—and descriptive analyses of individual buildings and projects, including the Salk Institute, the Kimbell Art Museum, the Yale Center for British Art, and the National Assembly complex at Dhaka, Bangladesh. A biographical chronology of the architect, a complete list of his buildings and projects from 1925 to 1974, an extensive bibliography, and an index conclude the book.

This volume, published to accompany a major traveling exhibition organized by The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, is the definitive scholarly and illustrative source for Kahn’s architecture.

David B. Brownlee is associate professor of the history of art. University of Pennsylvania.

David G. De Long is professor of architecture and chairman of the graduate program in historic preservation, University of Pennsylvania.

Vincent Scully is Sterling Professor emeritus of the hislory of art at Yale University.

Foreword and Acknowledgments

Richard Koshalek, Director

Sherri Geldin, Associate Director

Elizabeth A. T. Smith, Curator

Organized by The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, “Louis I. Kahn: In the Realm of Architecture” is the first comprehensive retrospective of this extraordinary architect’s work. It occurs at a highly appropriate time in the evolution of late twentieth-century architecture and underscores MOCA’s continued commitment to the investigation of the pivotal ideas and practices that have constituted the field of architecture since the mid-century. For contemporary architects searching for original expression in their work while seeking to connect it to larger cultural and societal forces, a study of the intensely focused career of Louis I. Kahn holds renewed value and relevance. For historians and critics grappling with the continuing evolution of architectural movements and directions, insights may be gained from contemplation of a body of work that defies simple categorization. For the general audience striving for a greater understanding of the world of architecture, the exhibition and the publication present a portrait of a great innovator, thinker, and teacher who believed passionately in architecture as one of the noblest, most spiritual, and most fundamental of human pursuits.

Closely examining all phases of Kahn’s work, MOCA’s exhibition and publication are organized into six major sections that interweave chronology, typology, and Kahn’s personal philosophy of architecture. The exhibition explores the entire body of Kahn’s work through a diverse selection of documents—drawings, sketches, paintings, scale models, archival and newly commissioned photographs, and artifacts. The exhibition and publication not only highlight the most significant and best-known architectural works by Kahn, but also examine and illuminate aspects of his career that have until now received only minimal attention.

The first section of the exhibition, titled “Adventures of Unexplored Places,” chronicles Kahn’s formative years—his Beaux-Arts training at the University of Pennsylvania, his early travels in Europe, his years of work in the offices of other architects, and his early independent designs for houses—through numerous drawings and artifacts that have never before been exhibited or published. Also presented here is a substantial subsection devoted to the crucial and innovative Philadelphia urban designs and City Tower series, spanning from the mid-1940s to the mid-1960s. The second section of the exhibition, titled “The Mind Opens to Realizations,” marks the true beginning of Kahn’s mature phase. With such works as the Yale University Art Gallery (1951—53), the Jewish Community Center, near Trenton, New Jersey (1954—59), and the Alfred Newton Richards Medical Research Building in Philadelphia (1957—65), Kahn began to firmly establish his national and international reputation.

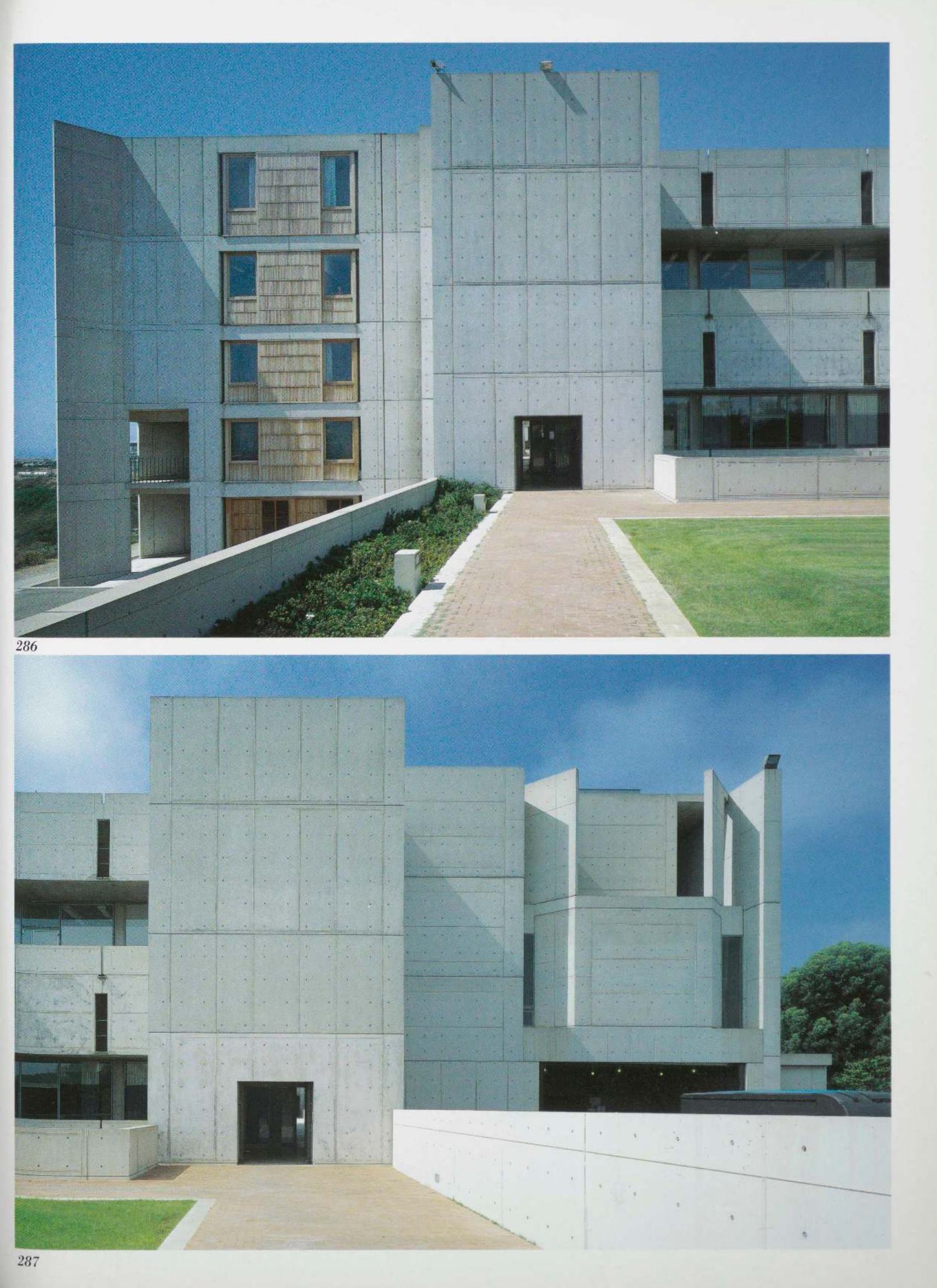

“Assembly ... a Place of Transcendence,” the third section of the exhibition, takes as its theme Kahn’s contribution to the design of religious and governmental institutional structures, notably Sher-e-Bangla Nagar, the Capital of Bangladesh in Dhaka (1962—83), and the unexecuted Hurva Synagogue, Jerusalem (1967—74). The exhibition’s fourth section, titled “The Houses of the Inspirations,” includes Kahn’s designs for centers of learning and research such as his Salk Institute for Biological Studies in La Jolla, California (1959—65), and the Indian Institute of Management in Ahmedabad (1962—74).

“The Forum of the Availabilities,” the fifth section, traces Kahn’s ideas at work in such projects as the Fine Arts Center, School, and Performing Arts Theater in Fort Wayne, Indiana (1959—73), and his late designs for public spaces including the Baltimore Inner Harbor (1969—73) and the Philadelphia Bicentennial Exposition (1971—73). Finally, in “Light, the Giver of All Presences,” Kahn’s reverence for light as the ultimate formgiver is shown through an examination of such works as the Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth, Texas (1966—72), the Yale Center for British Art (1969—74), and the unrealized Memorial to the Six Million Jewish Martyrs, designed for New York’s Battery Park (1966—72).

Representing the culmination of almost a decade’s work, the exhibition and the publication seek to examine Kahn’s career anew and to redefine his significance for our own time. They have been realized through the intense and longterm commitment of numerous individuals. Early in the planning phase, MOCA drew together a uniqrie group of collaborators whose expertise has greatly enriched all aspects of the project.

<...>

Introduction

Vincent Scully

This exhibition, like any work dedicated to Kahn, has been profoundly worth doing. Kahn was a supremely great architect. That fact is becoming more apparent with every passing year. His work has a presence, an aura, unmatched by that of any other architect of the present day. Far beyond the works even of Frank Lloyd Wright, Mies van der Rohe, and Le Corbusier, it is brooding, remote, mysterious. Wright’s buildings richly resolve the play of wonderful rhythms; those of Mies reduce space and matter to ultimate essentials, while Le Corbusier’s do something of everything, embodying the twentieth-century human gesture most of all, at first light and urbane, at the end heavy, primitive, violent. Kahn’s buildings, the very distillation of the twentieth century’s later years, are primitive too, but they are wholly devoid of gesture, as if beyond that, or of a different breed. Their violence is latent, potential, precisely because they do not gesture or seem to strike any attitude at all. They are above all built. Their elements—always elemental, heavy—are assembled in solemn, load-bearing masses. Their joints are serious affairs, like the knees of kouroi, but have the articulation of beings not in human form. Their body is Platonic, abstractly geometric in the essential shapes of circle, square, and triangle translated into matter, as if literally frozen into mute musical chords. They shape spaces heavy with light like the first light ever loosed on the world, daggers of light, blossoms of light, suns and moons. They are silent. We feel their silence as a potent thing; some sound, a roll of drums, an organ peal, resonates in them just beyond the range of our hearing. They thrum with silence, as with the presence of God.

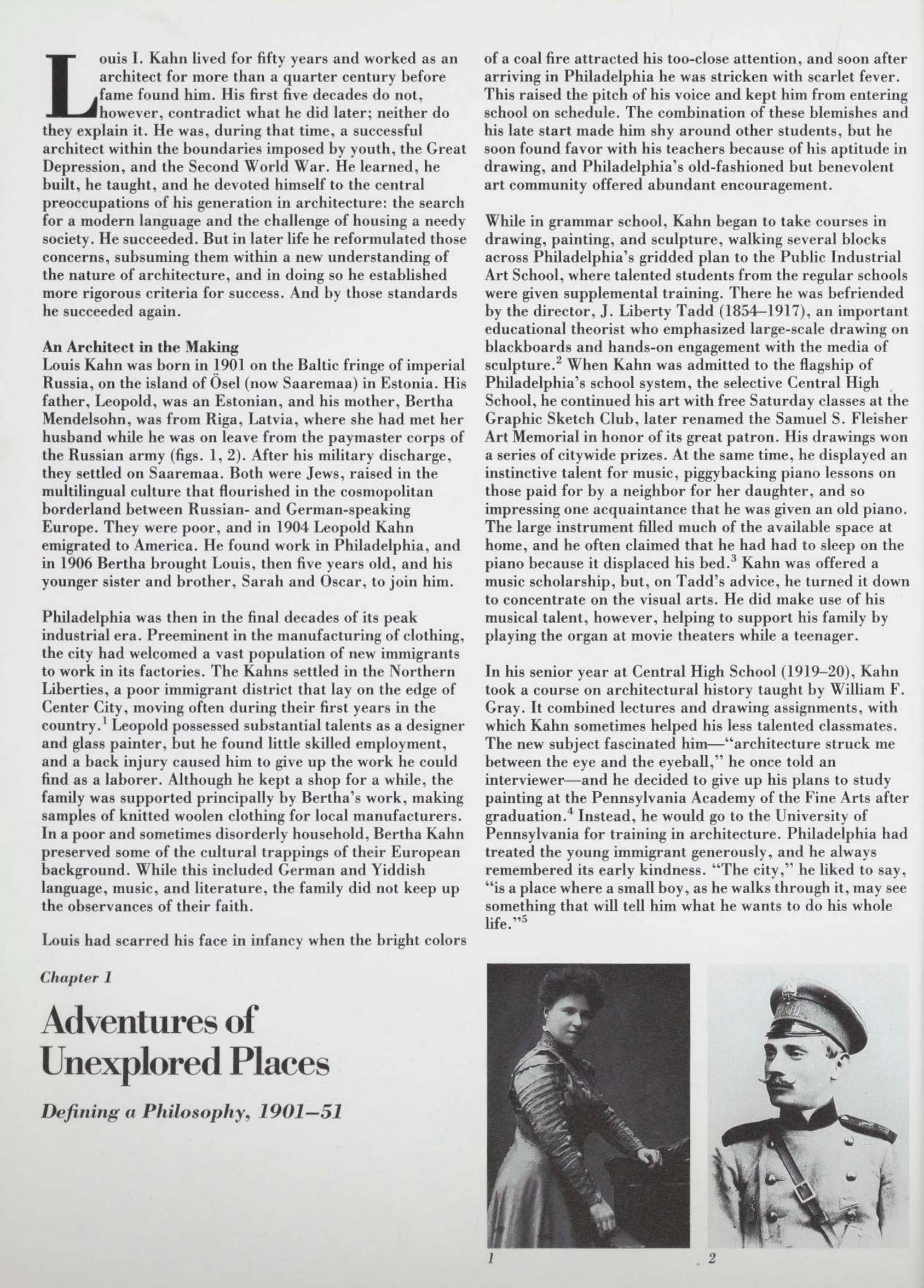

We try to think what other works of modern art have this curious high seriousness in the same degree: this determined link to the Ideal, this wholly specific physicality. Perhaps only some Russian novels come to mind, the works of Tolstoy most of all, perhaps those of Dostoyevski. I am reminded of the remark of a Russian student in Leningrad in 1965. It was at an exhibition of American architecture. Kahn and I were present. I ran a little seminar for especially interested students. Robert Venturi’s house for Vanna Venturi came under discussion. One student, mindful perhaps of the Soviet Union’s massive needs in housing and so on, asked, “Who needs it?” But another student instantly replied, “Everybody needs everything.” And I thought, there it is, the real stuff, the generous, excessive Russian soul. We tend to forget that Kahn was Russian, after all. Those blue Tartar eyes didn’t come from nowhere. Here we have to thank David Brownlee and David De Long for finding a photograph of Kahn’s father in his uniform. Poor, Jewish, Estonian, only a paymaster, and noncommissioned, he nevertheless comes across as an Imperial Russian officer to the life, a veritable Vronski, played by Fredric March. He looks much like his son, jaunty and proud, while Lou Kahn himself, at his graduation from the University of Pennsylvania, glares ferociously at the camera like the young Gorky or the student Tolstoy. And like them Kahn wanted “everything,” wanted to make everything true, right, deep, ideal, and whole if he could. I suppose he wanted all that more passionately than any other architect of our era has ever done. That is surely why, despite their obvious deficiencies in many fundamental aspects of architecture—contextuality, to name a contemporary interest, for one—Kahn’s works convince us that their own intrinsic being is enough. They are thus the single wholly satisfactory achievement of the late modernist aim in architecture: to reinvent reality, to make all new.

They are more than that, though. They begin something. They effectively bring the International Style to a close and open the way to a much solider modernism, one in which the revival of the vernacular and classical traditions of architecture, and the corollary mass movement for historic preservation, would eventually come to play a central role. Kahn’s greatest early associate, Robert Venturi, was to initiate these revivals of the urban tradition and to direct architecture toward a gentle contextuality unsympathetic to Kahn. Aldo Rossi in Italy was to move in a similar direction, creating a haunting poetry of urban types out of a vision of Italian vernacular and classical traditions not so different from that Kahn revealed in his pastels of Italian squares in 1950—51 and in some of his greatest buildings thereafter. Indeed, Kahn changed architecture for the better in every way, to some considerable degree changed the built environment as a whole and, beyond his knowledge or intention, made us value the fabric of the traditional city once more.

It is worth asking how this came about for Kahn. Here we should be as specific as Kahn himself. It came about because, after a lifetime of worrying about such things, Kahn discovered late in life how to transform the ruins of ancient Rome into modern buildings. This relationship, improbable enough on the face of it, is copiously demonstrated by the scores of photographs of Roman ruins that can be directly paired with views of almost all of Kahn’s buildings from the Salk Institute onward. Before this Kahn had already spent some years trying to find his way back to history. Cut off from his modern-classical education at Pennsylvania, and thus from history, by the rise of the iconoclastic International Style in the 1930s, Kahn was ready to look sympathetically at history once again at least from the time he began to teach at Yale in 1947. In 1950—51 he was reintroduced to Rome during his term as a fellow at the American Academy, where he studied Roman archaeological sites on his own and in the company of the great classicist Frank E. Brown, and traveled in Greece and Egypt as well. Soon he was making use of the Pyramids at Gizeh and of the Temple of Ammon at Karnak in various ways that I have discussed elsewhere.¹ It was only after he had adopted his early watercolors of San Gimignano for the towers of the Richards Medical Research Building, with attendant problems having to do largely with the reception of light, that the more purely Roman forms began to appear. They did so in a manner that suggests conversations with Robert Venturi, who had also spent a year in Rome, and most strikingly at the Salk Institute, especially in the project for the community center. “Ruins wrapped around buildings,” Kahn called the resultant glass-free, keyhole-arched, thermal-windowed Roman forms.

____________

¹ As in my introduction to the exhibition of Kahn's work at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in 1978 (The Travel Sketches of Louis I. Kahn [Philadelphia: Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, 1978]), to the Garland edition of Kahn’s drawings (The Louis I. Kahn Archive: Personal Drawings, 7 vols. [New York: Garland Publishing, 1987]), and to Jan Hochstim, The Paintings and Sketches of Louis I. Kahn (New York: Rizzoli, 1991). These articles touch on the Roman relationships as well.

Coincidentally enough, those ruins, open to the air, proved exactly suited to the climate and the simple brick technology of the subcontinent of India. They shaped Ahmedabad and Dhaka, where the crypto-portici can be compared with the Thermopolium at Ostia, while the main rooms at Ahmedabad closely echo the brick and concrete basilica of Hadrian’s market, and the National Assembly Building at Dhaka combines the Temple of Jupiter above Ostia’s forum with forms derived from plans of English castles and, as Brownlee and De Long suggest, with heaven knows what else. Most of all, Kahn’s “brick order” at Ahmedabad and Dhaka derives from Roman brick and concrete construction heavily filtered through Piranesi’s etchings of braced brick circles,² while a similar configuration in the portico of the outpatients’ clinic at Dhaka closely resembles Ledoux’s drawing of the architect’s all-seeing eye.³ Here the main historical point emerges clearly: Kahn was a Romantic-Classic architect, exactly as Piranesi and Ledoux had been. Like Piranesi he desired sublime effects (I have already tried to describe them), and like Ledoux he wanted them embodied in perfect, hard, geometric forms. Like those architects, and their many colleagues at the dawn of the modern age, Kahn wanted to begin architecture anew by concentrating upon the ruins of the ancient world and starting afresh from them. This is, I think, precisely why Kahn was indeed able to reinvigorate architecture toward the end of the late phase of the International Style. He was beginning modern architecture again as it had begun in the eighteenth century: with heavy, solid forms derived from structure rather than from the pictorial composition through which modern architects of the twentieth century had later attempted to rival the freedom of abstract painting. So Kahn’s work, despite his travel sketches, is itself never pictorial. It is primitively architectural, thus pre-pictorial. That is why Kahn was, like Cézanne in painting, a true primitive in the way he had chosen, always saying that he liked “beginnings” and that a “good question was better than the best answer.” It is no wonder that his buildings are full of ancient power. And, though he opened the way to the full classical revival of the present, he persistently refused to use classical details himself, confining himself always, in his own kind of modernist way, to the abstraction of the stripped ruin. Just so, in the last great years of his career, he would hardly use glass. This is true at Exeter, where he simply jammed the glass he did not need in India into the frame of a ruin and would not permit the four walls to join together as a completed building. At the Kimbell he employed only Romanoid arches, directly reflecting a specific set of ruins, and that was all, inside and out. Neither scheme could have been more purely Romantic-Classic.

____________

² As in his Antichità Romane, vol. 4, in H. Volkmann, G. B. Piranesi (Berlin, 1965), pl. 37.

³ Reproduced at about the same time, along with Piranesi’s Carceri and a number of nineteenth- and twentieth-century derivatives, in my Modern Architecture (New York: George Braziller, 1961), figs. 3—14.

This renders Kahn’s achievement at the Yale Center for British Art all the more surprising. Because there, in his last building, Kahn made what amounted to a great step forward in time and in the development of modern architecture itself. He stepped, in fact, from the eighteenth-century Romantic-Classicism of Piranesi and Ledoux to the nineteenth-century Realism of Labrouste. When, in the Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève, of 1843—50, Labrouste asked himself how the ruins of Greece and Rome could be truly rationalized into modern buildings on modern streets, he worked out a system of base, block, column frame, and infilling panels of solid and glass which became the classic modern solution to the problem of the urban building all the way on through Richardson and Sullivan to Mies van der Rohe and the present time. It is this system that Kahn adopted at Yale and in which, for the first time and with miraculous reflection, glass came to life in his design.

He therefore seems to have been at the beginning of some new integration in his work when he died. What he would have made of his followers, who have themselves remade the profession of architecture and begun to heal the wounds that the modern age has inflicted on our cities, is perhaps not hard to tell. He would not have liked any of their work very much. He was always the lone hero, after all, pursuing a lonely quest. And while it is true that the journey to Canaan was largely initiated by him, he never completed it himself, shaping his own kingdom outside the promised land.

This exhibition and its catalogue represent the first extensive scholarship devoted to Louis I. Kahn’s life and work since his drawings and office files became readily available for study. One is grateful to David Brownlee and David De Long, and to their students, for the good use to which they have put this material and for their painstaking documentation of all of Kahn’s most important buildings and projects.

Contents

Foreword and Acknowledgments.. 7

Richard Koshalek, Sherri Geidin, and Elizabeth A. T. Smith

Introduction.. 12

Vincent Scully

Prologue.. 15

Sherri Geldin

Chapter 1. Adventures of Unexplored Places.. 20

Defining a Philosophy, 1901—51

Chapter 2. The Mind Opens to Realizations.. 50

Conceiving a New Architecture, 1951—61

Chapter 3. Assembly... a Place of Transcendence.. 78

Designs for Meeting

Chapter 4. The Houses of the Inspirations.. 94

Designs for Study

Chapter 5. The Forum of the Availabilities.. 112

Designs for Choice

Chapter 6. Light, the Giver of All Presences.. 126

Designs to Honor Human Endeavor

Portfolio

Travel Sketches.. 146

Philadelphia Traffic Studies.. 151

Margaret Esherick House.. 152

Dr. and Mrs. Norman Fisher House.. 156

Mr. and Mrs. Steven Korman House.. 160

Yale University Art Gallery.. 164

Alfred Newton Richards Medical Research Building.. 172

Salk Institute for Biological Studies.. 180

First Unitarian Church and School, Rochester.. 192

Performing Arts Theater, Fort Wayne.. 202

Eleanor Donnelley Erdman Hall.. 206

Indian Institute of Management.. 214

Sher-e-Bangla Nagar, Capital of Bangladesh.. 232

Library, Phillips Exeter Academy.. 258

Kimbell Art Museum.. 266

Yale Center for British Art.. 288

Selected Buildings and Projects

Philadelphia Urban Design, Peter S. Reed.. 304

Yale University Art Gallery, Patricia Cummings Loud.. 314

Jewish Community Center, Susan G. Solomon.. 318

Alfred Newton Richards Medical Research Building, Alex Soojung-Kim Pang with Preston Thayer.. 324

Salk Institute for Biological Studies, Daniel S. Friedman.. 330

First Unitarian Church and School, Rochester, Robin B. Williams.. 340

Fine Arts Center, School, and Performing Arts Theater, Fort Wayne, Carla Yanni.. 346

Eleanor Donnelley Erdman Hall, Michael J. Lewis.. 352

Philadelphia College of Art, Kathleen James.. 358

Mikveh Israel Synagogue, Michelle Taillon Taylor.. 362

Indian Institute of Management, Kathleen James.. 368

Sher-e-Bangla Nagar, Capital of Bangladesh, Peter S. Reed.. 374

The Dominican Motherhouse of St. Catherine de Ricci, Michael J. Lewis.. 384

Library and Dining Hall, Phillips Exeter Academy, Peter Kohane.. 390

Kimbell Art Museum, Patricia Cummings Loud.. 396

Memorial to the Six Million Jewish Martyrs, Susan G. Solomon.. 400

Palazzo dei Congressi, Elise Vider.. 404

Yale Center for British Art, Patricia Cummings Loud.. 410

Bicentennial Exposition, Marc Philippe Vincent.. 414

The Louis I. Kahn Collection.. 420

Julia Moore Converse

Buildings and Projects, 1925—74.. 422

Chronology.. 430

Selected Bibliography.. 432

Annotated Bibliography.. 433

Index.. 440

Illustration Credits.. 447

Sample Pages

Download link (pdf, yandexdisk; 141 MB)

13 ноября 2019, 21:46

0 комментариев

|

Партнёры

|

Комментарии

Добавить комментарий