|

|

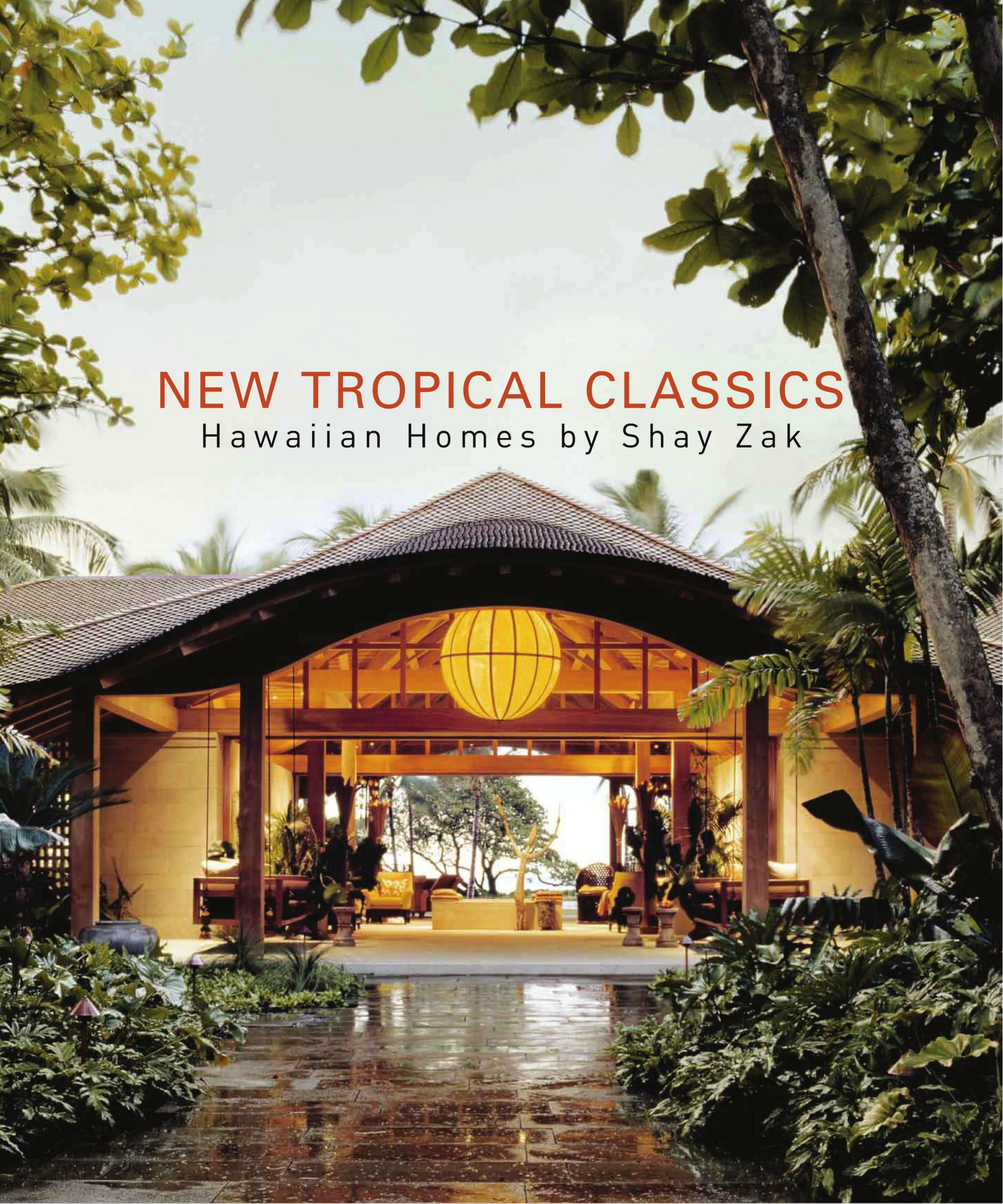

New Tropical Classics : Hawaiian Homes by Shay Zak. — Los Angeles, 2011New Tropical Classics : Hawaiian Homes by Shay Zak / Edited by Carolyn Horwitz and Anthony lannacci; Introduction by Erika Heet; Interview by Paul J. Karlstrom; Text by Carolyn Horwitz; Photography by Matthew Millman Photography. — Los Angeles : Architecture/lnteriors Press, Inc., 2011. — 191 p., ill. — ISBN 978-0-9835132-1-6MALAMA 'AINA: CARE FOR THE LANDErika Heet

For architect Shay Zak, "each house is a direct response to two things: the site and the client."

Faced with the eternal challenge of integrating a home into the landscape, Zak, who consistently extols the virtues of the natural world, uses nature as a divining rod that points to each house's ideal placement. Complementing that positioning is the influence of the people who will live there. On that theme, Zak often cites his mentor, the Pritzker Prize-winning Spanish architect Rafael Moneo, who once claimed: "Having a good client gives you the feeling that the work is wanted and that ultimately it is going to find shelter and protection in a broad sector of society. The client is, to some extent, the guarantee of the work's durability, success, and permanency."*

____________

* Zaera, Alejandro. "Winter 1994." Rafael Moneo 1967-2004: Imperative Anthology. Madrid: El Croquis, 2004. 21.

Zak likens his architectural progression over the last decade to his shifting taste in art, from plein air paintings to the work of abstract artists like Donald Judd and Ellsworth Kelly. Though Zak has made an intriguing evolution from neotraditionalism to a type of deconstructivism, hints of modernism reveal themselves in his more traditional houses, and shades of classical symmetry are apparent in his more minimal commissions. He names the 16th-century classicist Palladio as an influence yet is preoccupied with modern concepts such as negative space, indoor-outdoor living, and clean lines. Like most architects, he avoids being pigeonholed into one particular style, but when pressed to define his own refers to it as "modern classicism."

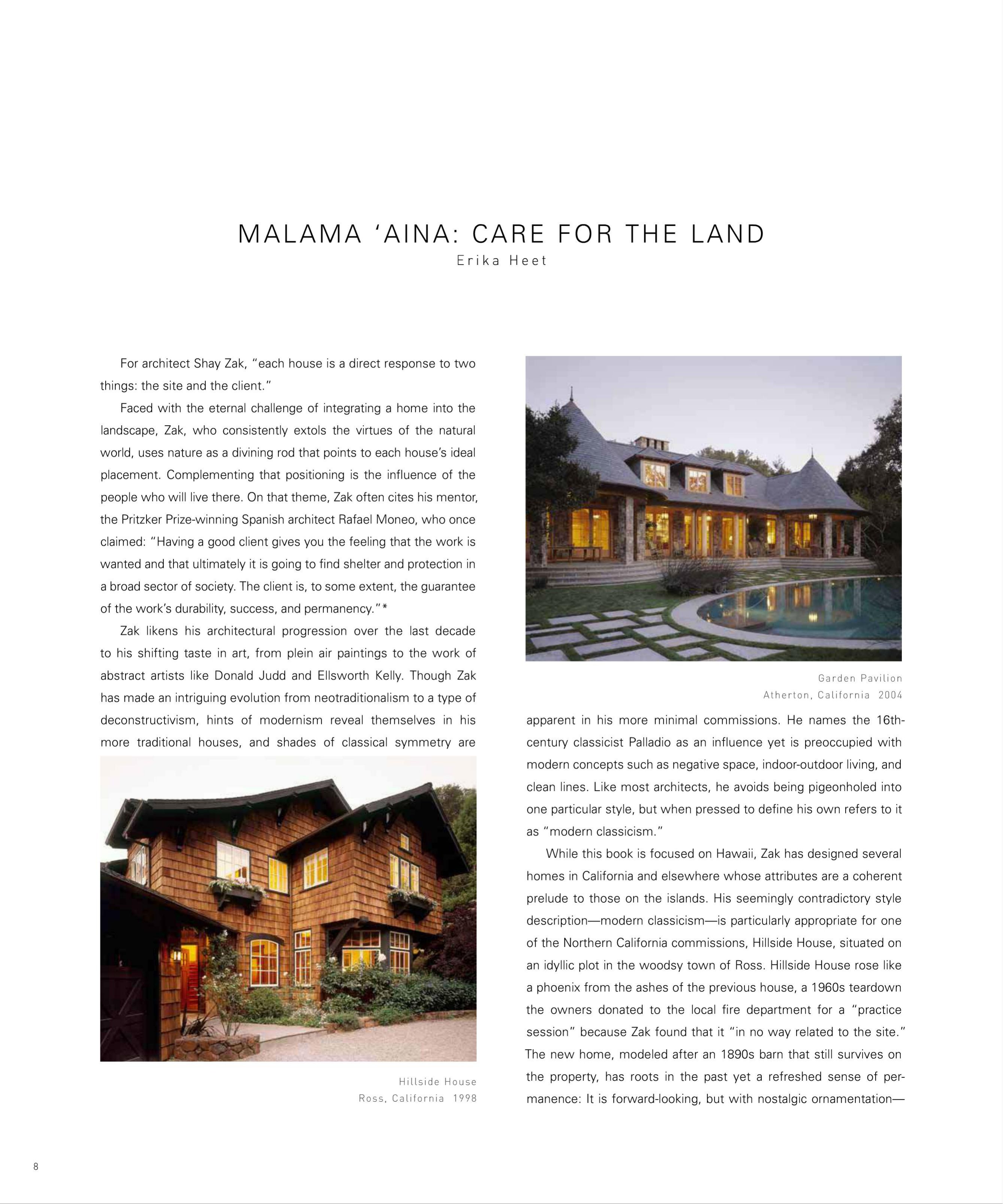

While this book is focused on Hawaii, Zak has designed several homes in California and elsewhere whose attributes are a coherent prelude to those on the islands. His seemingly contradictory style description—modern classicism—is particularly appropriate for one of the Northern California commissions, Hillside House, situated on an idyllic plot in the woodsy town of Ross. Hillside House rose like a phoenix from the ashes of the previous house, a 1960s teardown the owners donated to the local fire department for a "practice session" because Zak found that it "in no way related to the site." The new home, modeled after an 1890s barn that still survives on the property, has roots in the past yet a refreshed sense of permanence: It is forward-looking, but with nostalgic ornamentation—shingle cladding, Shaker paneling, wildflowers spilling from window boxes—that suggests an almost fairy-tale character.

Other Zak houses, mainly those in California, have a storybook quality as well, slightly reminiscent of the work of another Bay Area architect, Julia Morgan—only without the Gothic reverie. Architectural levity is found in the gently tapering turrets of Garden Pavilion, the corrugated roof of Ranch House, and the lodge-like brackets of Corner House that recall those in Greene and Greene bungalows. Quite conversely, most of the Hawaii houses are beachy and exhibit a beautiful practicality. Yet these houses are all related, and should be contemplated as an evolution, from the very well-behaved Hillside House to Hawaii's Assembly House and its devilish disarray of spaces.

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe is said to have remarked that "God is in the details," a deliciously arrogant, and inherently architectural, take on an old adage. Zak's singular designs include the siding on Ranch House, whose edges are finished with a wavy pattern, making the exterior appear, from some distance away, to breathe. Its corrugated metal overhangs, reminiscent of early homesteaded outbuildings of the West, are modernized as they jut out at stark angles. The gate pavilion at Assembly House, in addition to being clad in meticulously hand-set stonework, has a slim, vertical gun-slot detail facing the mountains to balance the huge floor-to-ceiling views to the sea. The hidden gardens of Courtyard House are a triumph. The "woven" stone walls that accent Stone House are an ingenious middle ground between open and closed. They long for secrets to be passed between them; they are a play within a play, a manifestation of the tinker's open fingers in A Midsummer Night's Dream. The cost and effort required to achieve these effects are not often referenced, though Zak admits that "it takes a lot of work to make them look this simple."

Every architect has signatures; Zak's include his Hawaiian roofs, heavily influenced by the Asian pagoda style. He begins each project from above, declaring, "I cannot conceive a floor plan without first thinking about what I'm going to do with the roof." At Stone House, the roof is topped with Balinese-inspired diamond-cut shingles that read as smooth fish scales, stacked exaggeratedly on the overhangs and poised like perfect rows of teeth. The home's arched "eyebrow" roof resembles the wings of a great bird, in the process of retracting as it settles back down to the ground. The houses are low-slung, nestled to the point of almost invisibility and seen from the air as a series of rectilinear pods.

Also fundamental to Zak's designs is the orientation of homes to their views. The California houses are strengthened by vistas of the inland topography—old oaks, Pacific Madrones, brush-covered hills, and verdant woods—but views are especially important at the seaside. With good reason, Zak is reluctant to change from the courtyard-home-lanai-pool-sea formula—one does not buy an ocean-front lot to turn one's back to it, and the seaside homes' more memorable features include the views across the great room and lanai to the pool and ocean beyond. In this book, in addition to architectural details, photographer Matthew Millman captures sweeping shots of what one looking out to open land or sea would frame with his hands, well before sinking the first shovel.

Defined by those Pacific views, Zak's Hawaii houses—under the spell of native customs and begging to be experienced barefoot—possess a sensuality that is wildly conducive to human existence. There is no feeling comparable to walking unshod over the island's spongy seashore paspalum grass, then onto the houses' varying surfaces of slate, stone, and smooth ipe wood. Trade winds sweep through their well-planned yet unseen axes, upending papers and flipping magazine pages as if by an invisible hand. From their floors to their splayed-radial ceilings, the houses are appointed with the unfussy, refined finishes for which Zak has scoured the world: teak, Western red cedar, Chinese slate. "Ultimately," he says, "I always search for creating the most appropriate and moving architecture experience while using the fewest elements possible."

Most notably in the Hawaii homes, family members and guests are given increasing architectural autonomy. When comparing the plans for the houses, a clear pattern emerges. Beginning with Beach House, one guest pavilion has snuck away from the main house, then Courtyard House is split into several freestanding buildings. Cluster House marks the first time Zak really "pulled everything apart," he says; followed by the Stone and Assembly houses, which became totally abstracted independent forms. The freestanding guest pavilions of Stone House—complete with private entrances and enclosed courtyards with inviting stone tubs and discreet outdoor showers—are a destination unto themselves, more secluded even than the master suite, which enjoys a place of prominence and shares an ocean view with the other primary spaces of the house. The sense of retreat at Stone House is underscored by the interior spaces, designed by San Francisco firm the Wiseman Group, where exquisite furnishings and soulful local art sing with subtle luxury and meld triumphantly with the architectural shell.

Zak's Hawaii houses mainly rest in the adjoining Hualalai and Kukio communities, on the temperate Kona-Kohala coast of the Big Island. Because he has designed many homes there, areas exist in which several of his commissions are situated together, giving certain streets more cohesion than others. In the case of the Courtyard and Stone houses, the two make for stunning next-door neighbors that play off one another with understated variations in tone. Subtly attacking the sameness of many of the surrounding buildings, Zak strives for the sublime. Because there is a tension that arises from the undeniable spirit that flows through the Hawaiian islands, and from the fact that the limited open land is sacred to its people, one does not dare go into a building project without first considering what the Hawaiians call malama 'aina, or care for the land. This dictum has guided the locals for centuries in their quest to maintain a deep appreciation for living in harmony with nature. Zak's work thrives especially in concert with clients who honor his respect for what and who was here before, and for what and who may exist here later.

Reverence for the land is not limited to Zak's Hawaii houses; it has driven his California commissions as well. He has walked each site with the clients and studied every plane, every view, to find the proper placement. He has eschewed slavish interpretations of local vernacular, yet has paid very close attention to this language, allowing the houses, though unique, to suggest that they and their inhabitants truly belong where they are. They evoke the feeling of having remained in-situ for decades among the historic farms and barns.

More than two thousand miles across the sea, on the shores of Hawaii, the owners are rewarded with the same sense of home. They light their tiki torches when they are, as they say, "in residence." And when they are not, they shut the rows of pocket doors—first the screens, then the slat blinds, then the heavy wood doors—and the houses sleep, and wait for their inhabitants to return and allow them to come alive again.

[CONTENT]

MALAMA 'AINA: CARE FOR THE LAND. Erika Heet 8

BUILDING CHARACTER Paul J. Karlstrom 14

BEACH HOUSE 20

COURTYARD HOUSE 30

CLUSTER HOUSE 48

STONE HOUSE 64

ASSEMBLY HOUSE 86

DOGLEG HOUSE 118

DESCEND HOUSE 140

CLOISTER HOUSE 164

Credits 188

Sample pages

Download link (pdf, yandexdisk; 112 MB).

Все авторские права на данный материал сохраняются за правообладателем. Электронная версия публикуется исключительно для использования в информационных, научных, учебных или культурных целях. Любое коммерческое использование запрещено. В случае возникновения вопросов в сфере авторских прав пишите по адресу 42@tehne.com.

13 января 2018, 16:31

0 комментариев

|

Партнёры

|

Комментарии

Добавить комментарий