|

|

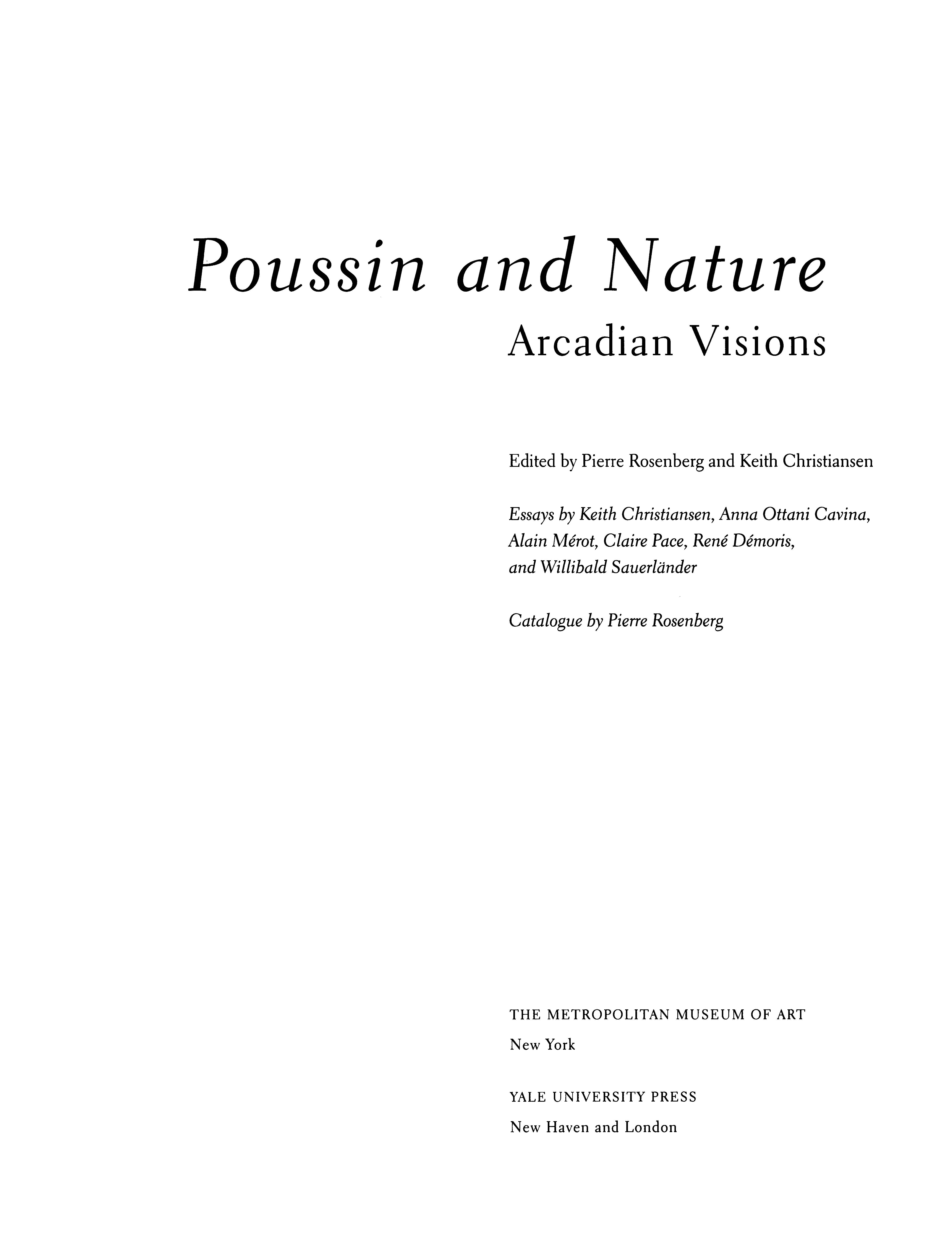

Poussin and Nature: Arcadian Visions. — New York, 2007  Poussin and Nature: Arcadian Visions / Edited by Pierre Rosenberg and Keith Christiansen ; Essays by Keith Christiansen, Anna Ottani Cavina, Alain Mérot, Claire Pace, René Démoris, and Willibald Sauerländer ; Catalogue by Pierre Rosenberg. — New York : The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2007.—XVII, 414 p., ill. — ISBN 978-1-58839-242-8

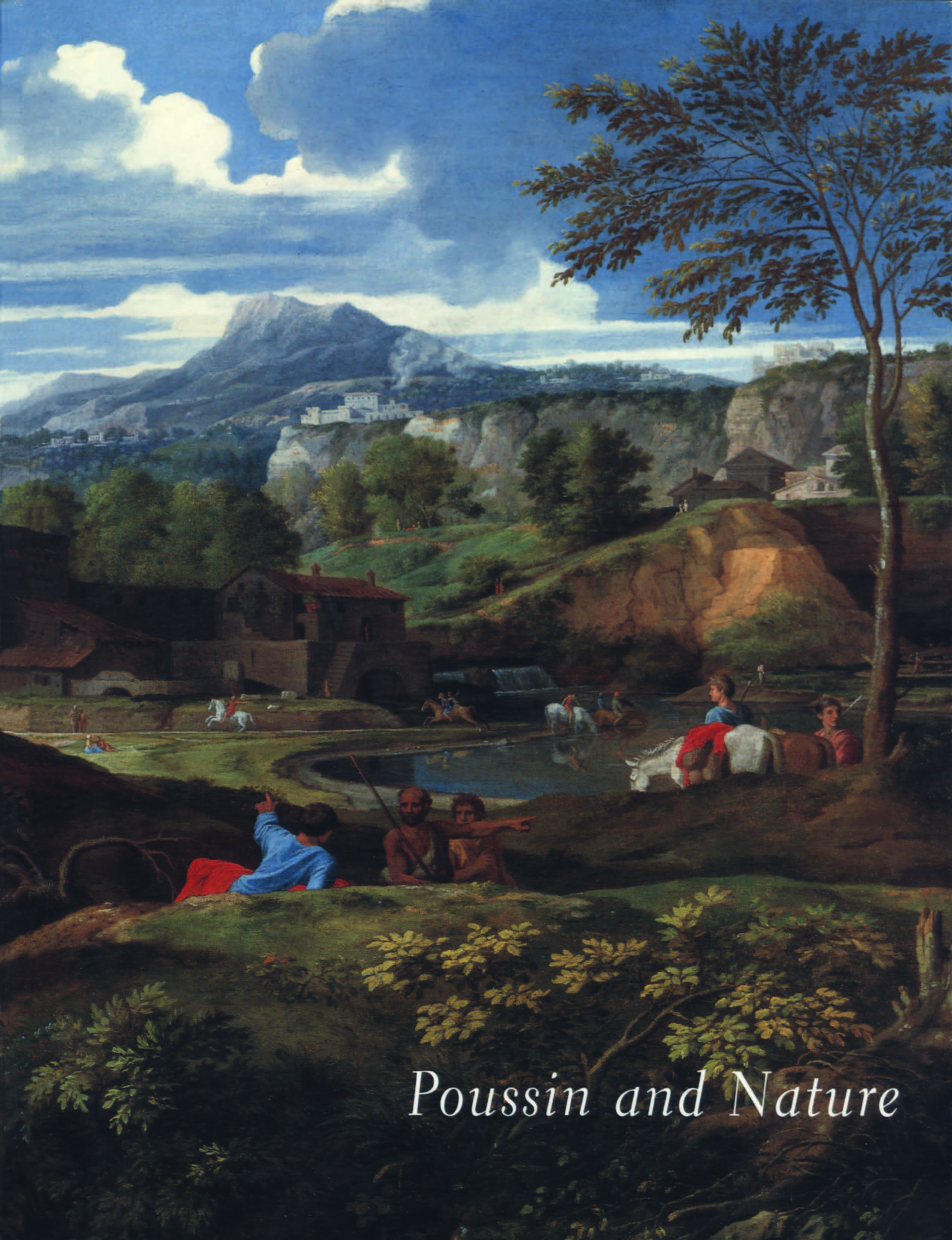

The work of the great French painter Nicolas Poussin (1594–1665) is most often associated with classically inspired settings and figures depicting solemn scenes from mythology or the Bible. Yet he also created some of the most influential landscapes in Western art, endowing them with a poetic quality that has been admired by artists as different as John Constable, J. M. W. Turner, and Paul Cézanne. As the British critic William Hazlitt noted in 1821, "This great and learned man might be said to see nature through the glass of time."

This volume, which accompanies a major exhibition at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, is the first in-depth examination of landscapes in Poussin's work. The artist's pictorial imagination and intelligence are affirmed in forty-five canvases, ranging from early Venetian-inspired pastorals to austere, grandly structured scenes and deeply poetic landscapes designed as metaphors for or allegories of the processes of nature. It is in his late landscapes that Poussin's imagination and his preoccupation with fate and humankind's interactions with nature are given free rein. Nearly fifty of the artist's drawings—the most luminous of which were done en plein air—provide fascinating insight into Poussin's thematic interests and working methods. Essays by internationally renowned scholars examine the visual, literary, and philosophical influences on Poussin as well as his relationships with his patrons and his place in the art-historical canon. Comparative paintings, drawings, and engravings by Poussin and others illuminate the essays and complement the exhibited works.

Following the essays and a brief overview of key dates in the artist's life, noted Poussin scholar Pierre Rosenberg provides a detailed catalogue of the 113 works in the exhibition, exploring questions of authorship, dating, interpretation, and execution, often righting earlier mistakes and raising new questions. In a separate section of the catalogue, Rosenberg considers a selection of drawings traditionally attributed to Poussin but now considered more likely to be by followers and contemporaries.

This groundbreaking book gives the fullest possible representation of Poussin as a painter of landscapes, at the same time providing a unique occasion to explore the most personal side of this great artist's creative achievement.

Pierre Rosenberg is a member of the Académie française and Honorary President-Director of the Musée du Louvre, Paris.

Keith Christiansen is Jayne Wrightsman Curator of European Paintings at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

This catalogue is published in conjunction with the exhibition “Poussin and Nature: Arcadian Visions,” on view at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, from February 12 to May 11, 2008. It was held at the Museo de Bellas Artes, Bilbao, from October 8, 2007, to January 13, 2008.

Directors' Foreword

That Nicolas Poussin (1594–1665) was one of the major figures of seventeenth-century painting and the founder of French classicism is well known. That he was also one of the great painters of landscape, and that his landscape paintings have had a profound impact on European art, are far less widely recognized. This is the first exhibition devoted exclusively to Poussin as a painter of landscapes, and we fully expect that these supremely poetic works of art will come as a revelation to many viewers.

Landscape painting was an activity that engaged Poussin only sporadically, and more so at the end of his career than at the beginning. Visitors will discover, however, that from the outset Poussin was as concerned with the landscape settings of his pictures as he was with their narrative subjects. An ardent student of nature, he transformed the genre to suit his elevated notion of the maniera magnifica, or Grand Manner, and in so doing conferred on it a new status. The mere recording of visual experience—landscape as an imitation or transcription of the world around us—did not interest him. He painted no topographical “views,” and even in his drawn oeuvre—abundantly represented here—identifiable sites are few; rather, in his landscapes we encounter nature reconfigured and ennobled—not as we encounter it in our everyday life, but as we might imagine it to be (to paraphrase the seventeenth-century critic Roger de Piles). Dense with literary associations and profoundly poetic, the artist’s landscapes propose—again in the words of de Piles—“an agreeable illusion, and a sort of enchantment.” In his conception of landscape painting, Poussin represented the polar opposite of most of his contemporaries in Holland, and also of those later, nineteenth-century traditions of realism that have so influenced our own ideas about landscape painting.

As in the work of his great compatriot Claude Lorrain, Poussin’s pastoral landscapes are embellished with subjects derived from classical and Renaissance literary sources. Although the two artists were friends and made excursions together into the Roman Campagna to draw from nature, the spirit of their drawings and paintings could not be more different. Almost invariably, a Claude landscape presents us with a light-filled vista set off by a dark coulisse of trees, a hillock, or the noble forms of a classical temple or Roman villa. The luminous distance is often measured by the rays of the setting sun reflecting off the eddying waves of a harbor. Light—whether the soft, suffused light of dawn, the golden light of late afternoon, or the intensely colored light of evening—is the leitmotif of Claude’s art. His clouds hang in the sky like airy puffs; his trees are feathery, their leaves gently moving in the breeze. There is a pervasive and deeply lyrical serenity in his landscapes that is further enhanced by the delicate detail of buildings and those curiously tall, spindly figures that add a nostalgic, dreamlike quality to the whole.

In contrast with Claude’s vision, Poussin’s rigorously critical frame of mind confers on nature an air of order and permanence. If his early landscapes remind us of and were inspired by the sensual world of Titian, his mature landscapes—those produced after about 1640—are the products of an intense and even mystical reverence for the Roman Campagna that is as great as Claude’s. Poussin's counterbalance to this engagement with nature was a no less intense critical detachment and a remarkable sense of artistic purpose. He orders his responses by employing a careful sequence of solids and voids to construct space and by emphasizing vertical and horizontal elements that meet at right angles to each other. A placid lake—its mirrorlike surface magically reflecting the buildings and figures along its edges—or a curving road or river defines the middle ground, and a distant mountain range closes off the composition. Trees and the cubic forms of buildings—sometimes humble, sometimes majestic—confer an architectural solidity on the composition, and the clouds are arranged in sequential planes that create a further sense of order and compositional unity. It is by these means, as much as by the subjects he introduces, that Poussin's landscapes acquire a moral as well as poetic dimension. The quality of permanence and inevitability in his paintings, which deeply impressed Cézanne, made Poussin a crucial figure in the genesis of modern painting. (The importance of Poussin's landscapes for Cézanne was the subject of a memorable exhibition held in Edinburgh in 1990; remarkably enough, it is the only exhibition prior to this one to deal specifically with Poussin as a painter of landscapes.)

Poussin's involvement with landscape painting may have been sporadic, but it was not casual, and his landscape works have had an influence out of proportion to their number. They are, indeed, central to any history of European painting, which is why an exhibition attempting to understand the artist's engagement with nature is so important—and long overdue.

As early as 1649, the French printmaker Abraham Bosse observed, “I have even seen landscapes that he [Poussin] made for pleasure, that should hold the first rank for this kind of work." What Bosse could not have imagined was the admiration Poussin's landscapes would continue to garner over the next three hundred years, for the list of artists who studied and learned from Poussin's landscapes is as impressive for its variety as it is for its length. In the seventeenth century, he had both imitators and followers, the most accomplished of whom was his brother-in-law Gaspard Dughet (also known as Gaspard Poussin). In France, Francisque Millet and Sébastien Bourdon built their reputations as landscape painters upon the esteem Poussin's work enjoyed among collectors.

What may come as a surprise to many is Poussin's pervasive impact on nineteenth-century artists, to the point that French painters studying in Rome sought out the sites his landscapes evoked—the so-called promenade du Poussin (on this subject, see Anna Ottani Cavina's essay in this catalogue). In his treatise on landscape published in 1800, Pierre-Henri Valenciennes laid down the challenge: “If, after this great man [Poussin], no one to equal him can be found, do not believe the thing impossible: the flame of genius has not gone out." That flame was rekindled by Camille Corot, who sought to endow his landscapes with that aura of a mythic past recaptured—he was sometimes criticized for being too slavishly reverential toward his great forebear. Remarkably, Jean-François Millet—an artist with a very different sense of artistic purpose, though not lacking in a sense of nostalgia for the past—was scarcely less admiring: his Harvesters Resting (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston) pays obvious homage to Poussin's Ruth and Boaz: Summer (cat. 67). J. M. W. Turner and Théodore Gericault found their romantic vision of nature confirmed in Winter: The Flood (alas, too fragile to be lent to this exhibition; see fig. 42), in which they discovered hints of the sublime. If John Constable responded to the naturalistic effects of the Landscape with a Man Washing His Feet at a Fountain (cat. 38), Samuel Palmer was captivated by the visionary quality of Poussin's Landscape with Polyphemus (fig. 36)—and so, it would seem, was the Swiss symbolist Arnold Böcklin.

Viewed through the lens of Bocklin, Poussin's work appeared to be a prelude to early twentieth-century metaphysical painting. Giorgio de Chirico, for one, discerned disquieting associations within Poussin's landscapes: “The trunks, and branches, studied like human bodies, make one think of certain nudes by antique sculptors, or of certain perfectly muscled limbs." Cézanne passed on a very different response to the creators of modernism in France. At a generation removed from each other, Matisse and Balthus set up their easels in the Louvre before Poussin's haunting Echo and Narcissus (fig. 25)—that masterpiece of his Venetian style —recollections of which can be detected in Matisse's La Bonheur de vivre (Barnes Foundation, Merion, Pennsylvania) as well as in Balthus's The Mountain (The Metropolitan Museum of Art).

This broad and remarkably varied response to Poussin's achievement alerts us to the richness of his vision—one for which the terms classical or ideal seem completely insufficient. As Kenneth Clark observed in his masterful book Landscape into Art, Poussin “combined in such full measure the ideal and the real. His scrupulous sense of design was nourished on observation; his most exalted visions remain concrete. [. . .] And it is this sensuous grasp of organic as well as abstract form that makes Poussin's late landscapes so inexhaustibly satisfying." The constant dialogue between observation and poetic vision that is the basis of the artist's finest work will be apparent to visitors to this exhibition as they move from drawings to paintings and back again.

It is important to understand that for Poussin observation was not a passive act: it implied critical evaluation. His paintings incorporate then-current ideas about ways of perceiving nature: of, for example, the transformation of color with distance—what is commonly referred to as atmospheric perspective—or the laws governing reflection. They are also based on a theory of poetic invention first elaborated in the Renaissance.

The notion of Poussin as a cerebral artist—the quintessential peintre-philosophe—has been a mixed blessing, contributing in no small degree to the idea that his work is accessible only to an intellectual elite and that the key to his work lies in the unraveling of the subjects he treats. Few have seen the dilemma more clearly than André Gide, who in his 1945 book on the artist observed: “I would go even further: as often happens, Poussin ran the risk of being hindered by intelligence. The miracle is that Poussin was painter enough, great painter enough, so that the container, under the excessive weight of its contents, did not give way; so that his triumphant conception knew how to subdue the material even while glorifying it.”

Above and beyond whatever significance we may read into his often haunting and mysterious subjects—the Landscape with a Man Killed by a Snake (cat. 44) has elicited a flood of interpretation without any final resolution to the matter—what was important to Poussin was the act of poetic invention: the Horatian view of painting as a kind of mute poetry. As Willibald Sauerländer demonstrates in his eloquent essay in this catalogue, Poussin found his most important sources of inspiration—his paradigms—in the poetry of Ovid and Virgil. His is an Arcadian vision, but it is of an Arcadia that has not escaped intimations of mortality and death: Et in Arcadia Ego—the ego signifying both the presence of Death in Arcadia and Poussins projection of himself into his paintings. As with poetry, his work demands serious engagement on the part of the viewer, but in return it promises an intensity of aesthetic as well as intellectual pleasure. In one of his last letters, Poussin declared that the aim of painting is delectation, the object of its subject matter to enable the painter to demonstrate his talent and industry, and that its various parts “spring from the talent of the painter and cannot be learned. They are like Virgil's Golden Bough which none can find or pick, unless he is guided by destiny.”

* * *

It has been the aim of the organizers of this exhibition to give the fullest possible representation of Poussin as a painter of landscapes so as to provide a unique occasion to encounter the most personal side of this great artist's creative achievement. For this we have been dependent on the goodwill and supportive collaboration of museums and private collectors throughout Europe and America. Inevitably, there have been disappointments due to lending restrictions, prior commitments, or issues of condition. And it proved impossible to secure everything for both institutions. Thus, some of Poussin's most beautiful drawings will be seen only in Bilbao, and some key paintings will be shown only in New York. We were especially sorry that it proved impossible to borrow the Landscape with Polyphemus from Saint Petersburg (a work whose fragile condition does not allow it to travel) and the Landscape with Hercules and Cacus from Moscow, for these are among the greatest of Poussin's mature landscapes. On the other hand, thanks to a special arrangement with the Ministry of Culture in Serbia and His Royal Highness Crown Prince Alexander II, the Landscape with Three Monks, also known as La Solitude—a work not exhibited outside Serbia since 1931—will be shown in New York following its cleaning and conservation. It is the closest thing to a pure landscape that Poussin ever painted and will come as a revelation. Special thanks is owed the Prado in Madrid, the Staatliche Museen in Berlin, the National Gallery in London, and the Louvre in Paris, which have been extraordinarily generous with multiple loans, but to all the lenders listed in these pages we extend our heartfelt gratitude.

Although this exhibition has been a collaborative venture, the initiative for it originated with the Museo de Bellas Artes in Bilbao. Pierre Rosenberg was invited to be the guest curator, and it is to him that we owe the selection of the works as well as the entries in the catalogue. He has been actively engaged at every stage of its organization. Indeed, the project would have been inconceivable without his enthusiastic commitment. To him goes our deepest appreciation. Miriam Alzuri and Keith Christiansen were the organizers at Bilbao and New York, respectively.

At Bilbao, the exhibition has been generously supported by the Fundación Bilbao Bizkaia Kutxa, a regular sponsor of the Museo de Bellas Artes, in celebration of the centennial of both institutions.

The exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum has been made possible thanks to generous grants from The Florence Gould Foundation and The Isaacson-Draper Foundation. All visitors to the exhibition in New York are in their debt.

Philippe de Montebello

Director, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Javier Viar

Director, Museo de Bellas Artes de Bilbao

Preface

Poussin and Nature: odd as it seems, no monographic exhibition has yet addressed this theme, one that from the seventeenth century onward has attracted the attention of writers and poets, painters and art historians. Since the end of World War II, there has been a resurgence of interest in the subject, with an ever-increasing number of publications taking up the issue. These publications have concerned Poussin's landscape drawings as well as his paintings; they have explored questions of authorship, dating, interpretation (more or less esoteric), and even, sometimes, beauty. If pressed to name only one specialist fascinated by the connections between Poussin and nature, I would cite Anthony Blunt. His work on the artist's drawings—for example, chapters 9 and 11 of his Mellon Lectures, delivered in 1958 and published in 1967—remains exemplary. (I nonetheless confess that my own approach to Poussin is closest to that of Denis Mahon rather than to Blunt's.)

How did the present exhibition come about? The Museo de Bellas Artes in Bilbao celebrates its centennial in 2008. To recognize this landmark, its director, Javier Viar Olloqui, and its director of exhibitions, Miriam Alzuri, wished to organize an important event. I suggested an exhibition on the place of landscape in Poussin's work. Such an exhibition would provide an opportunity to tackle, visually, certain issues still vigorously debated today: Poussin's early work in Rome before 1630; his ambitious approach to landscape after 1630 and prior to 1640; the great poetic examples of his final years, which are without parallel in European painting of the seventeenth century; and his accepted landscape drawings as well as those that had often been attributed to him in the past.

It might be noted here, as an aside, that interest in Poussin has a long history in Spain. The Prado possesses many key works by Poussin, which have been well studied by Spanish specialists—Juan J. Luna in particular—and frequently exhibited. (The magisterial monograph on Poussin by Otto Grautoff, which appeared in German in 1914, was published in Spanish in 1945, whereas neither French nor English editions exist. Similarly, Jacques Thuillier's 1974 monograph on Poussin, part of the Classique de l'Art series, appeared in Spanish in 1975.)

One painting seemed to me crucial as the focal point of the exhibition: Blind Orion Searching for the Rising Sun, in The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (cat. 63). I brought up the matter with Keith Christiansen. Not only was he favorably inclined to grant the loan, but for some time he had been nurturing the idea of an exhibition on Poussin and nature. Philippe de Montebello, director of the Metropolitan Museum (with whom I share the same birthday as well as a tremendous admiration for Poussin), also considered such a project highly appealing. Various museums and other art institutions in the United States have devoted important exhibitions to Poussin—Knoedler & Co. Galleries in New York in 1940 (whose catalogue I refer to in my entries, not only because of the exhibition's organizer, the great Poussin scholar Walter Friedlaender, but also for the fine text by Marguerite Yourcenar, which has otherwise remained unpublished); The Minneapolis Institute of Arts and the Toledo Art Museum in 1959; and The Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, in 1988, among others. Yet the curious fact remains that, until now, the artist has been neglected by New York museums, despite the fact that the first authentic Poussin to enter the United States (in 1871) was the Metropolitan Museum's Midas Washing at the Source of the Pactolus (cat. 20), and that today there are in America about thirty works by the artist. (Perhaps one day these works will be reunited with pictures whose attribution has been questioned.)

The history of Poussin's paintings in America—including The Death of Germanicus in the Minneapolis Institute of Art and the Holy Family on the Steps in the Cleveland Museum of Art—would be worth recounting, and there is still no study of the history of Poussin scholarship in America, stretching from the first generation of Jewish-German refugees (how can I not again mention Walter Friedlaender, whom I had the privilege of knowing?) to today's specialists, whose writings find a welcome place in the columns of The Art Bulletin. Here I must express my sorrow at learning of the death of Konrad Oberhuber, a brilliant connoisseur and Poussin scholar whose ideas were as bold as they were unorthodox.

With the addition of a second venue, in New York, the exhibition acquired an entirely new breadth and ambition. My colleagues and I knew that the restrictions of various drawing collections would require us to split their loans between Bilbao and New York, but we also realized that the Metropolitan Museum's participation would make it easier to obtain many of the desired loans. We set out to make the venues in Bilbao and New York as alike as possible, but in a number of key cases this objective was not obtainable.

In the end, the exhibitions in Bilbao and New York fulfill my wishes and our dreams. It is true that the Musée Condé at Chantilly as well as the Musée Bonnat in Bayonne are prohibited from lending their wonderful drawings, and that, for the same reason, the notable but little-known painting Landscape with Three Nymphs at Chantilly is likewise absent. We had also hoped for the loan of the Kingdom of Flora in Dresden; the Landscape with the Funeral of Phocion from the collection of the earl of Plymouth (fortunately, its companion [cat. 43] is here); the Landscape with Polyphemus from The Hermitage in Saint Petersburg (it was also absent from the monographic exhibition in Paris in 1994–95); the Landscape with Hercules and Cacus from the Pushkin Museum in Moscow; and, from the Louvre (which, it must be noted, has been exceptionally generous), the Echo and Narcissus and the canvases depicting autumn and winter from the series of the Four Seasons. Yet there have been welcome surprises as well: the Landscape with Three Monks, also known as La Solitude (cat. 53) makes its first appearance outside Serbia since 1931. Thus the exhibition really has satisfied my expectations.

The number of individuals I must thank for their help is considerable: their names will be found in the Acknowledgments (as always, I fear I have inadvertently omitted some names, for which I am truly sorry). In addition:

My mother, who just turned ninety-nine, has read my manuscript with her usual sharpness.

I would like to thank my two colleagues Miriam Alzuri and Keith Christiansen, who not only gave me encouragement and daily assistance, but who also, and above all, joined their efforts to obtain the desired loans.

I owe a special debt of gratitude to Olivier Lefeuvre. He was my collaborator from the very beginning of the project. To him fell the heavy responsibility of keeping records on each work to be shown, ferreting out information from the library, correcting my mistakes, and rectifying my omissions.

To all I give my warm thanks.

Pierre Rosenberg

Member of the Académie française

Honorary president-director of the Musée du Louvre

Contents

Director's Foreword.. VII

Preface.. XIII

Acknowledgments.. XVI

Lenders to the Exhibition.. XVII

Introduction: Encountering Poussin

Pierre Rosenberg.. 5

The Critical Fortunes of Poussin's Landscapes

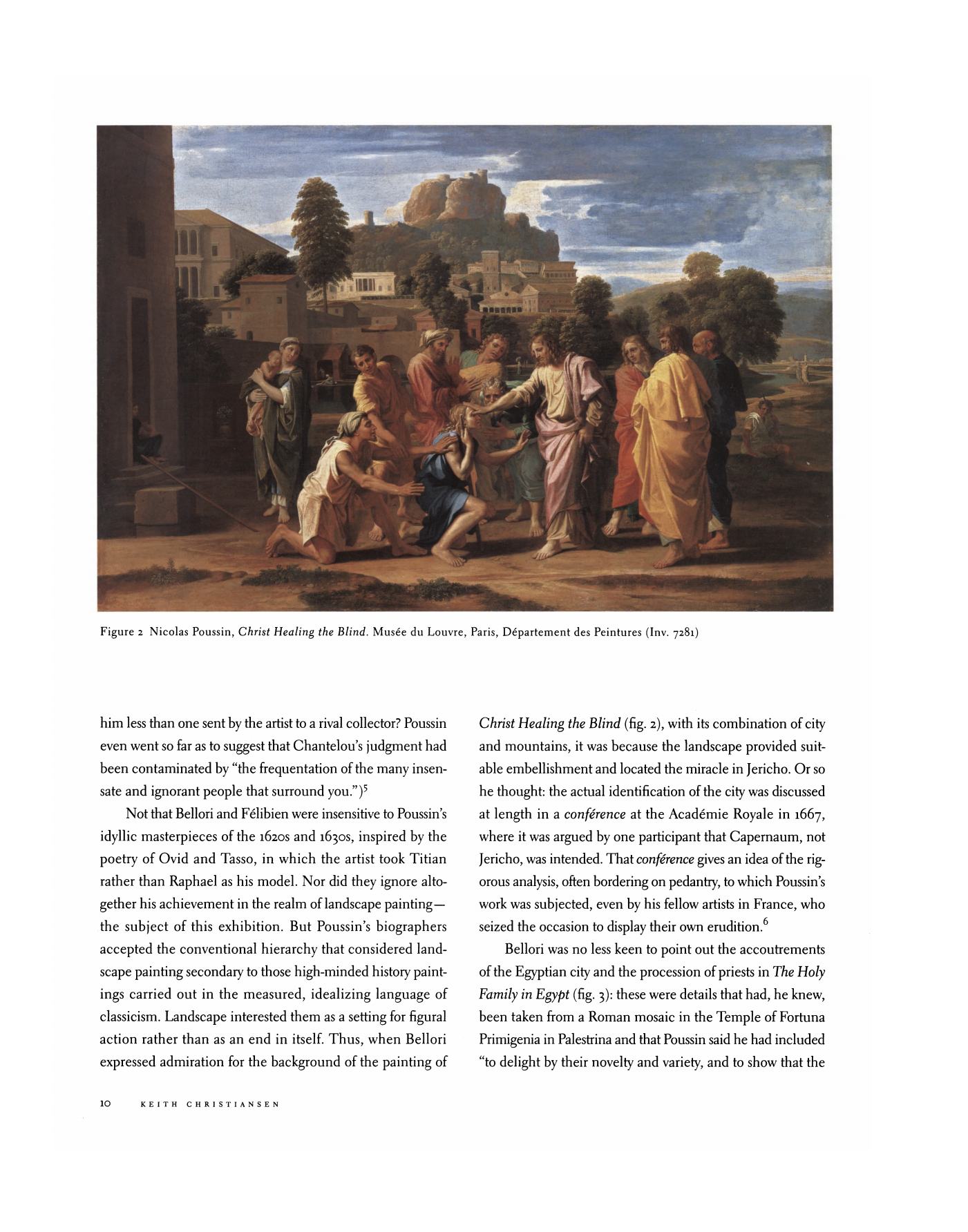

Keith Christiansen.. 9

Poussin and the Roman Campagna: In Search of the Absolute

Anna Ottani Cavina.. 39

The Conquest of Space: Poussin's Early Attempts at Landscape

Alain Mérot.. 51

"Peace and Tranquility of Mind": The Theme of Retreat and Poussin's Landscapes

Claire Pace.. 73

From The Storm to The Flood

René Démoris.. 91

"Nature through the Glass of Time": A Reflection on the Meaning of Poussin's Landscapes

Willibald Sauerländer.. 103

A Brief Biography of Nicolas Poussin

Keith Christiansen.. 119

Catalogue

Pierre Rosenberg

I. Poussin's Early Years in Rome.. 127

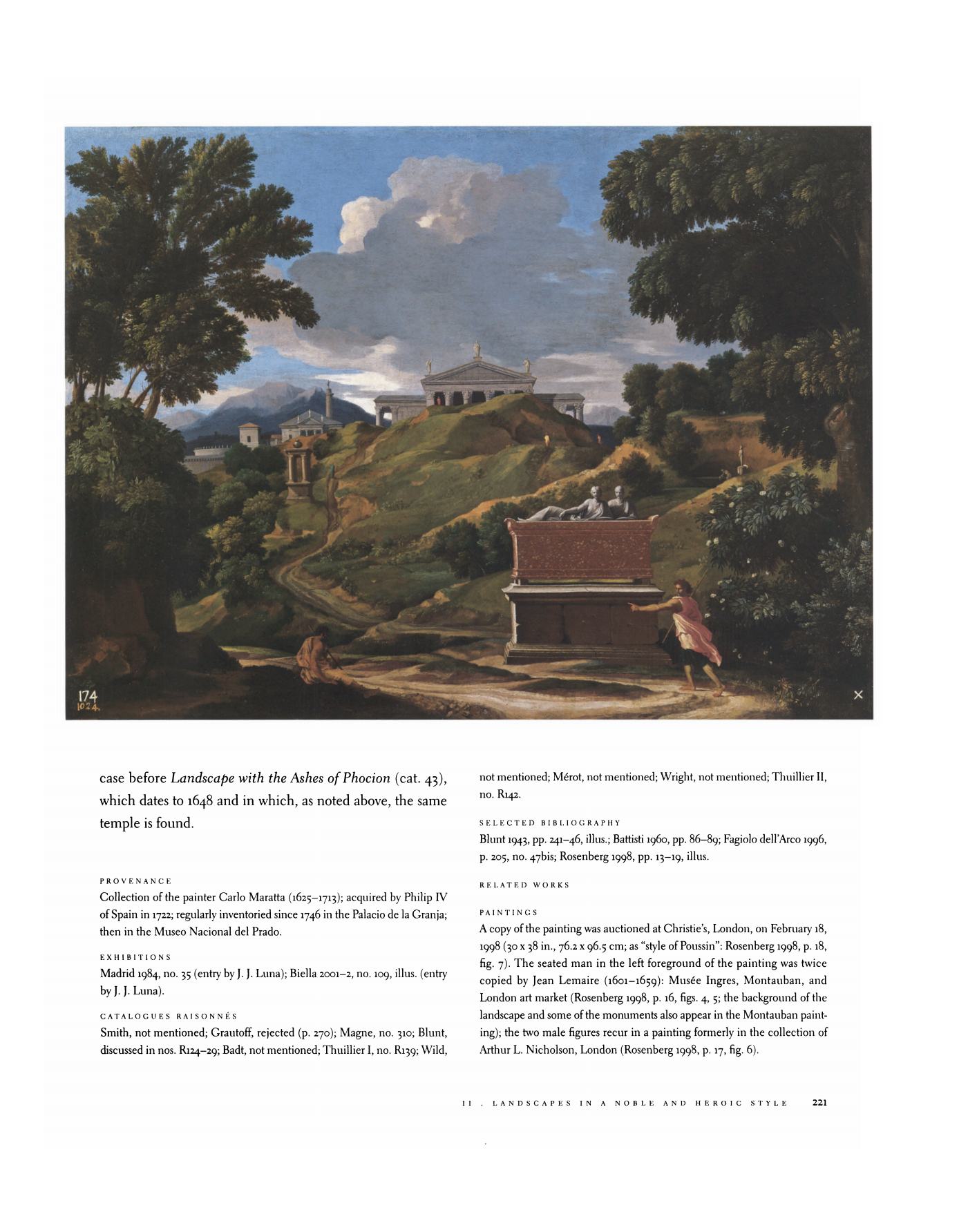

II. Landscapes in a Noble and Heroic Style.. 187

III. The Poetic Landscapes.. 269

IV. Poussin's Landscape Drawings.. 307

V. The "G Group" Drawings.. 343

Bibliography.. 373

Exhibitions.. 392

Index of Works by Nicolas Poussin.. 398

Index.. 406

Photograph Credits.. 413

Sample pages

Download link (pdf, yandexdisk; 139 MB).

27 февраля 2020, 20:16

0 комментариев

|

Партнёры

|

Комментарии

Добавить комментарий