|

|

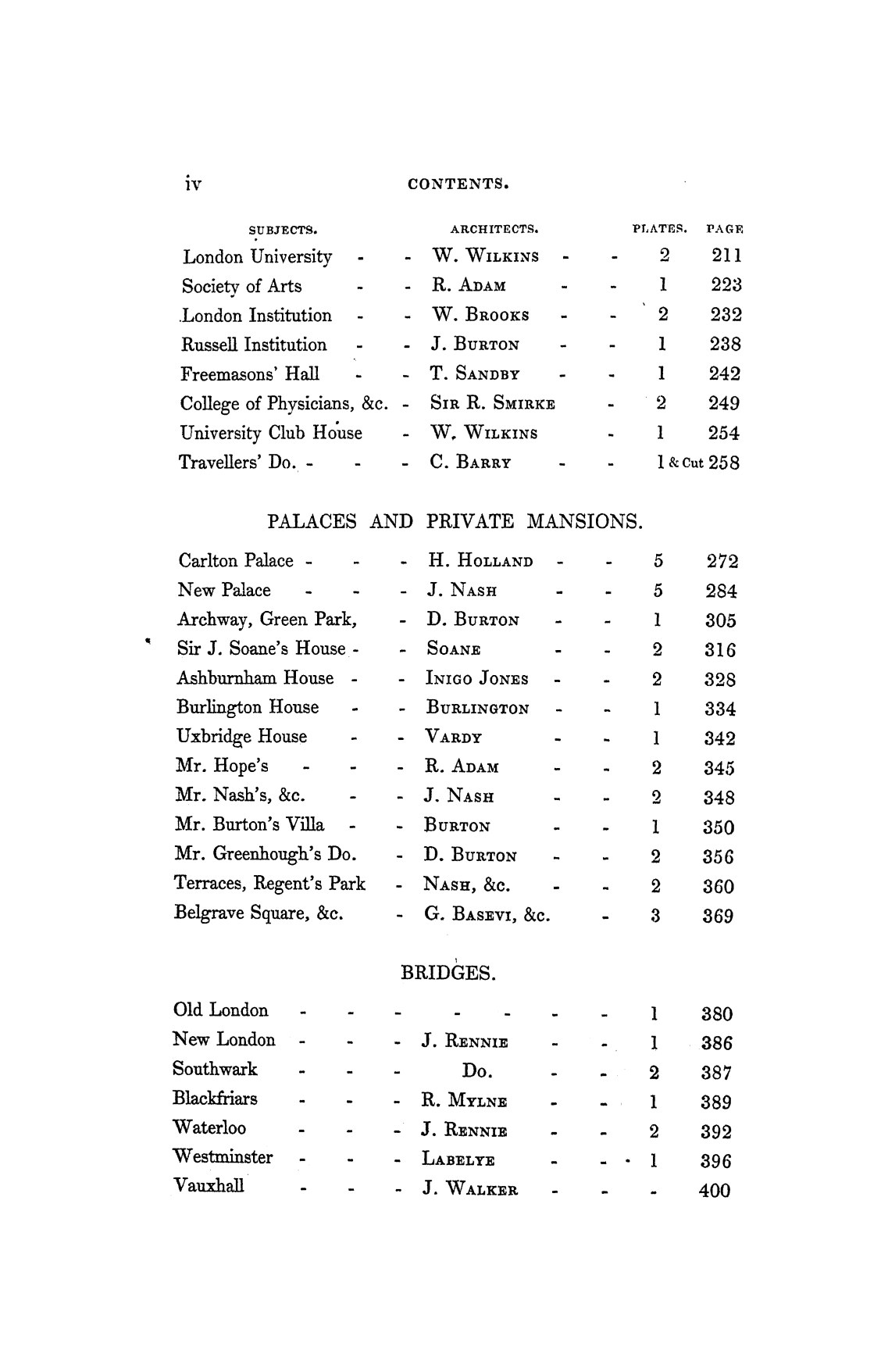

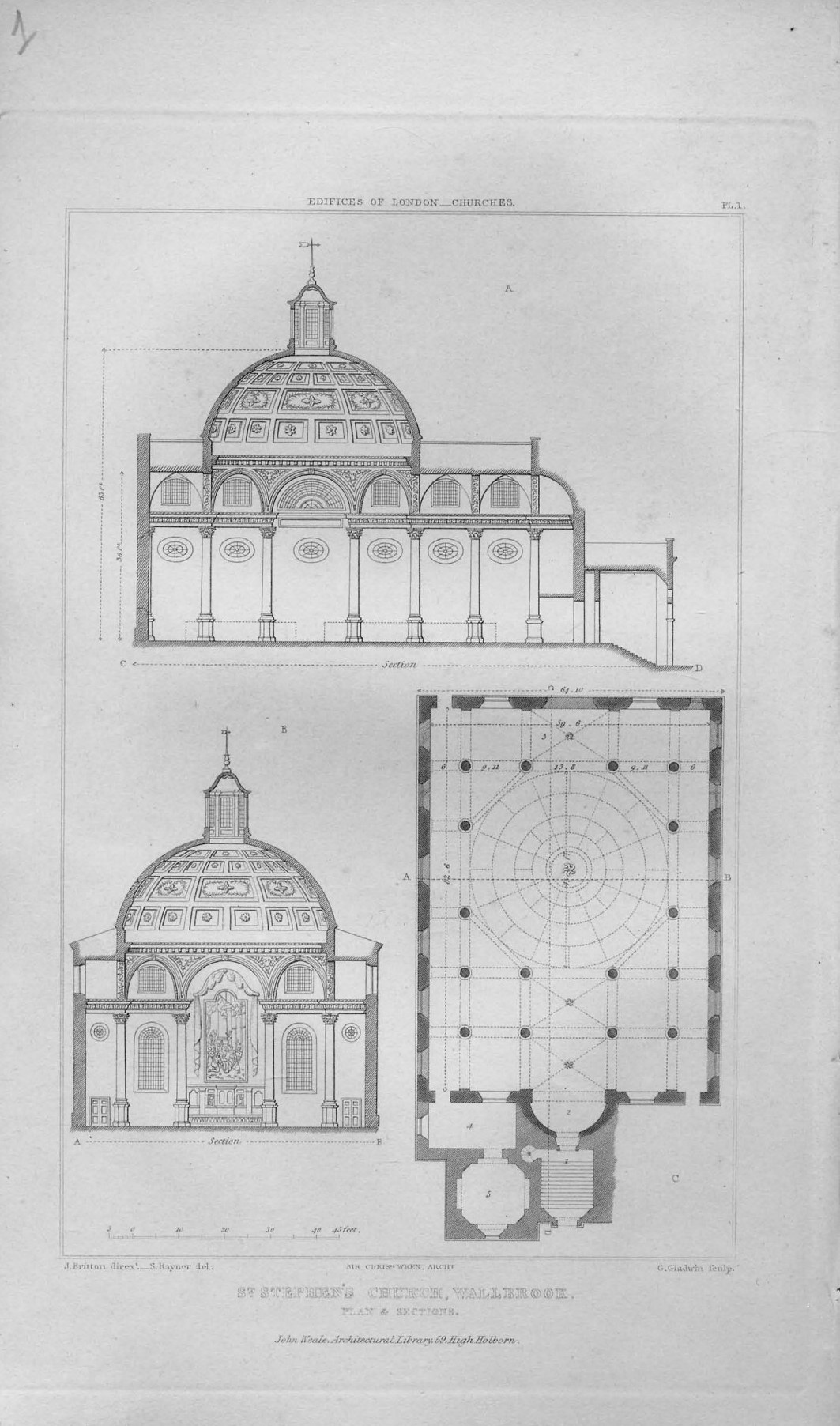

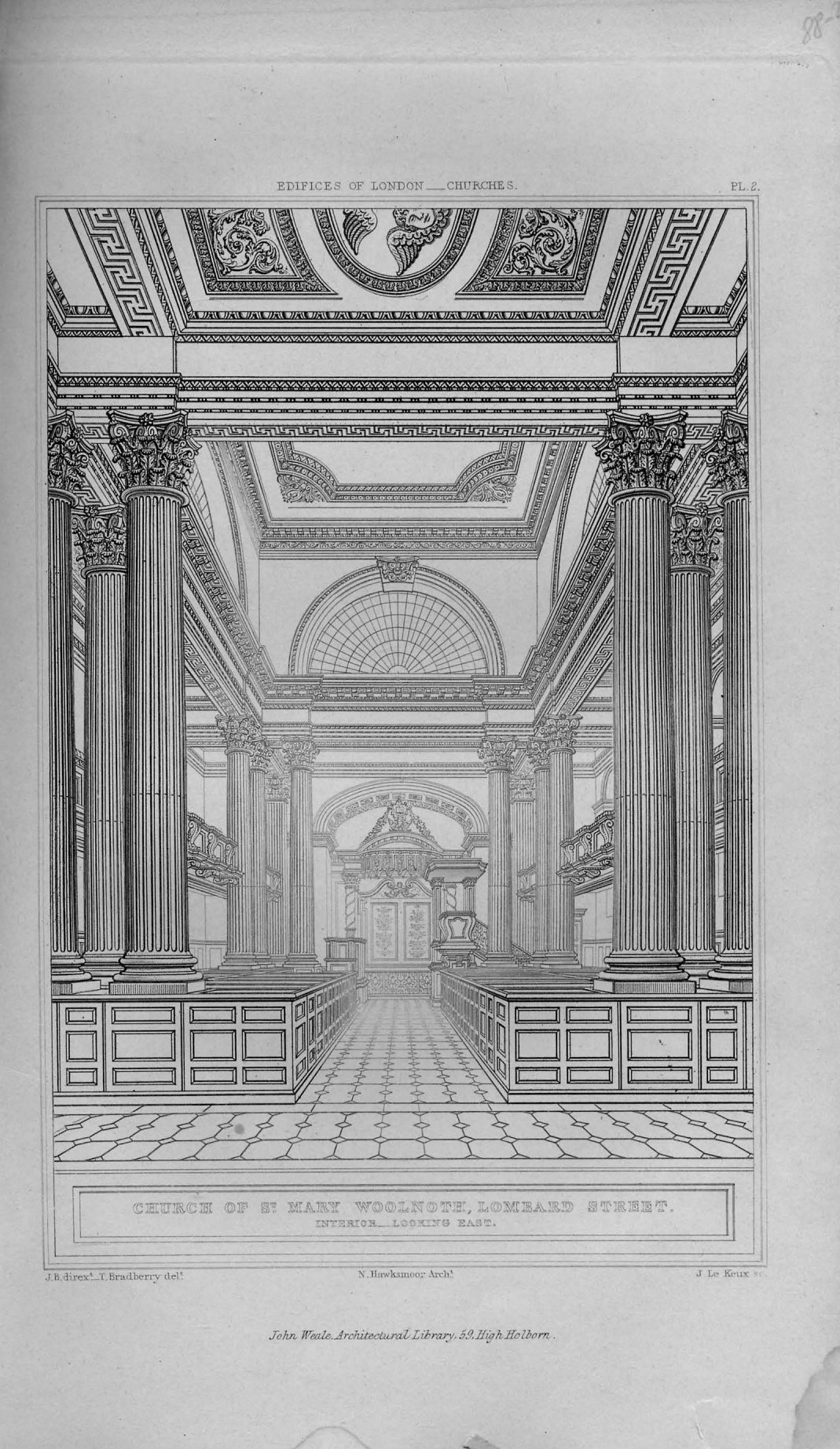

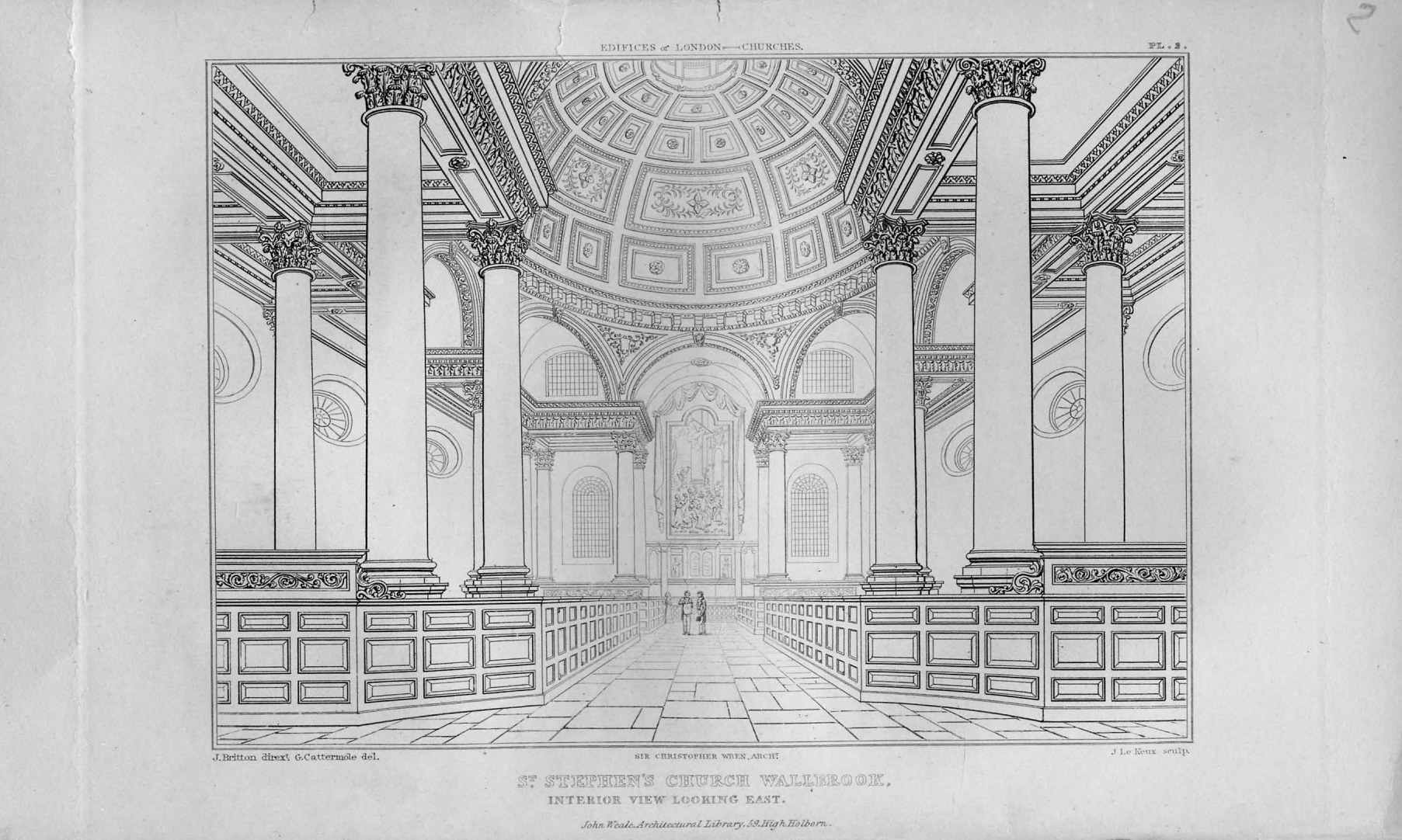

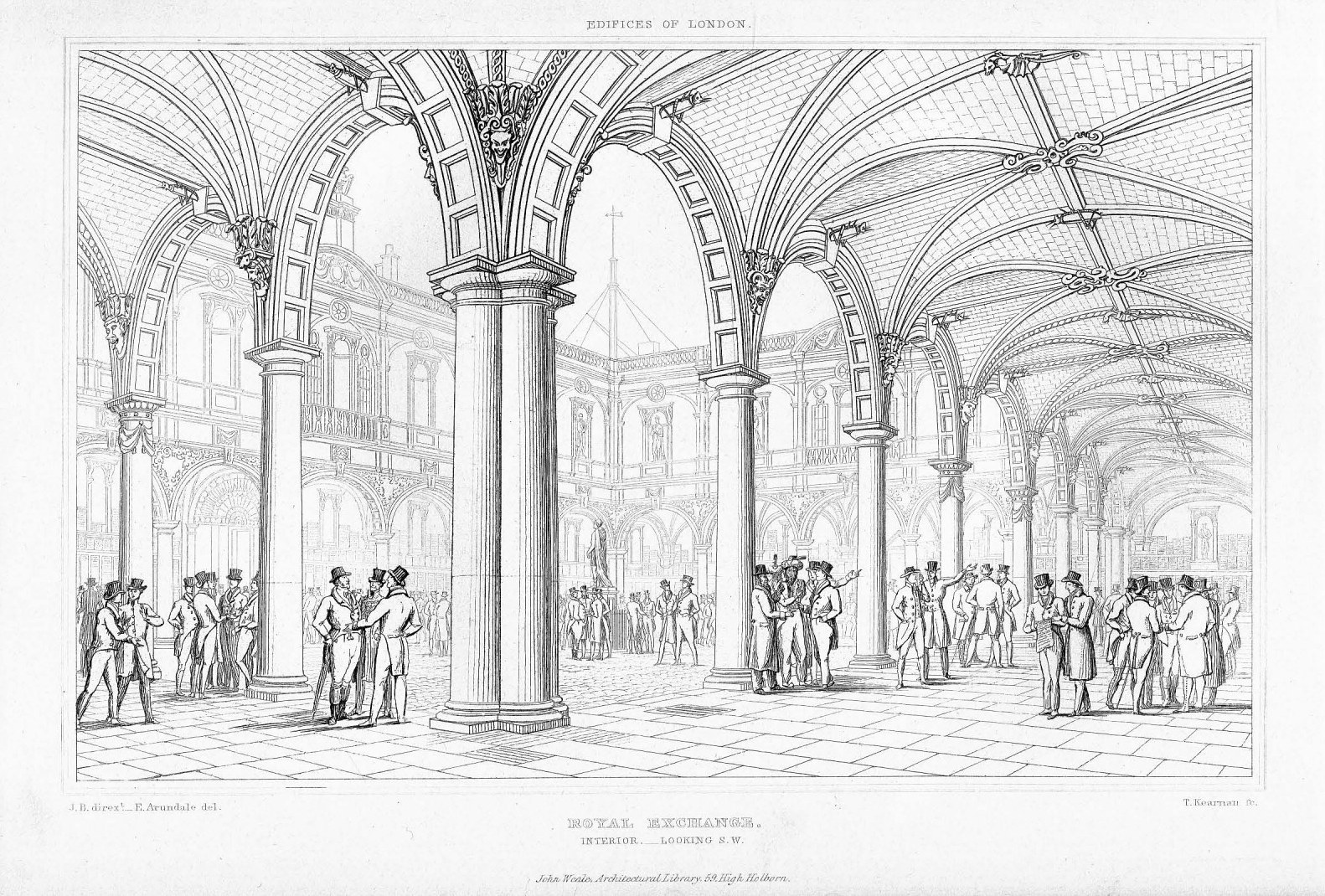

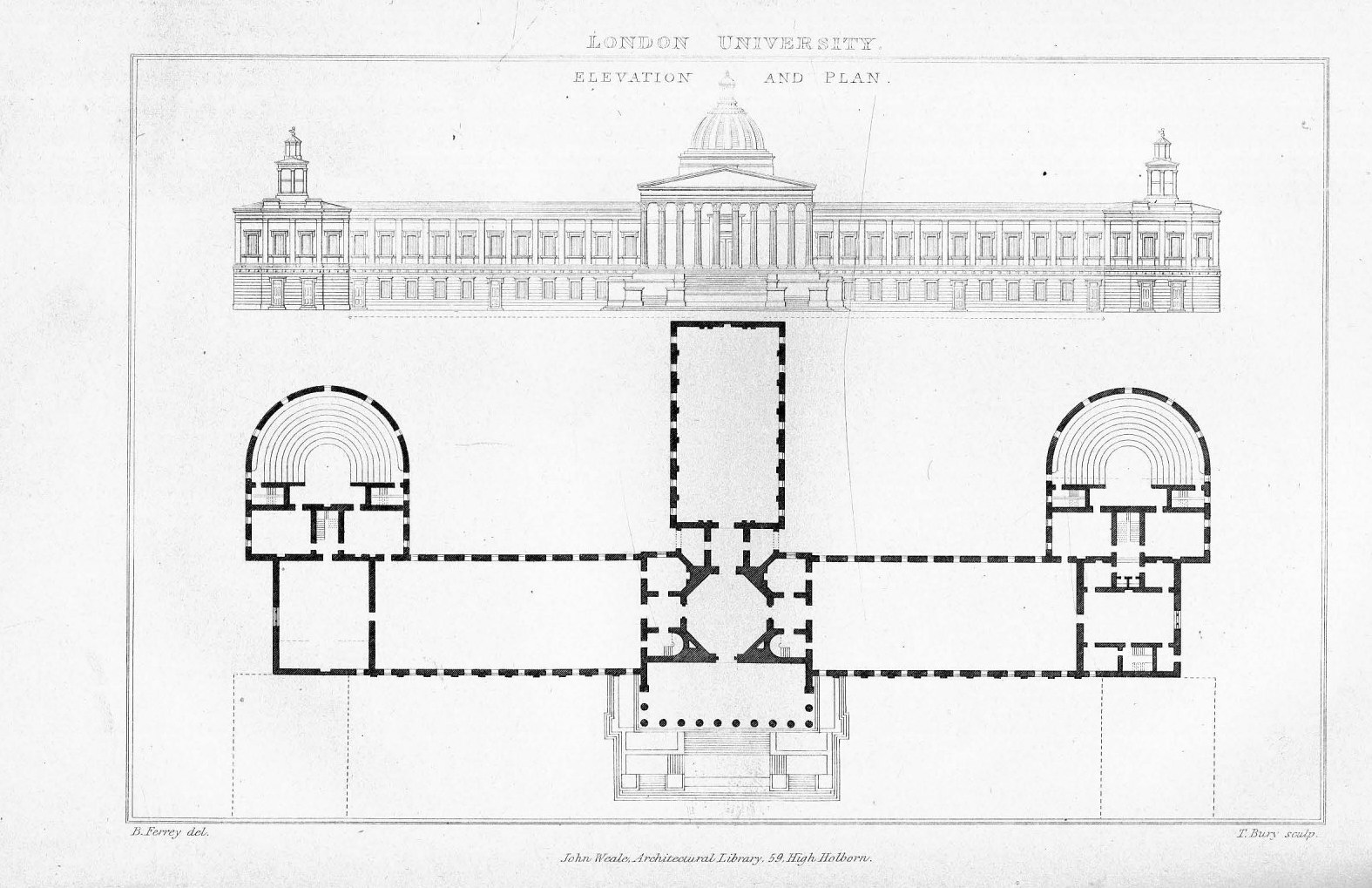

Pugin and Britton. Illustrations of the public buildings of London : With historical and descriptive accounts of each edifice : In 2 volumes. — London, 1838Illustrations of the public buildings of London : With historical and descriptive accounts of each edifice : In 2 volumes / by Pugin and Britton. — Second edition, greatly enlarged by W. H. Leeds. — London : John Weale, 1838.

PREFACE.

To many it has been matter not only of regret, but of surprise, that a work like the present, so convenient and economical in form, and interesting to others as well as professional men, should not have been continued beyond the two volumes originally published; more particularly as in the interim from their appearance, a variety of structures of more or less merit and note have been added to the public edifices of the metropolis. That there is an abundant supply of fresh subjects for such purpose, will hardly be disputed; many of them, as it is hoped this new Edition will satisfactorily testify, even more interesting than several of those previously represented. Yet although there are ample materials for a third or even a fourth volume, the present publisher deems it more adviseable, as the work is now out of print, to commence with an entirely new edition containing several hitherto unedited buildings.

Besides the additions both in regard to Plates and their descriptions, others to a very considerable extent have been made by the present Editor, both in the form of Notes, and of Remarks appended to the accompanying letter-press by other writers. The opinions of the latter have been left untouched by him, even when decidedly at variance with his own; in order that the reader may adopt whichever shall appear to him the most judicious, and the best-founded. All that has been done in the way of altering the original letter-press, has been confined to abridging several of the articles, by paring away what was evidently extraneous matter, what related only very remotely indeed to the buildings themselves, and was by no means in accordance with the character of a work that is most undisguisedly of a strictly architectural nature, therefore not at all likely to find purchasers among those who seek merely historical and topographical information. It was probably thought that the insertion of such irrelevant matter, might both help to make up for the deficiency of architectural explanation and comment, and serve to render the work more popular and acceptable to the general reader; yet whatever may have been the motive, it must be allowed to have been very mistaken policy to adapt the work rather to the tastes of those who were not likely to encourage it to any extent, than of the class to whom it directly addressed itself; and many of the articles were so barren of remark and criticism, so overloaded with details to be collected from topographical histories, and bearing only incidentally upon the professed subjects, that the former bore about the same proportion to the latter, as the item of bread did to that of sack in the fat Knight’s bill.

With this conviction, the Editor has, among sundry other excrescences, expunged the whole of the account of the Progress of the Drama in England, as being a grossly palpable hors d’œuvre, having no more connexion with the history and description of the Theatres themselves as buildings, than Covent Garden Market has with Covent Garden Church. Neither was that inter-chapter or interlude at all in keeping with the rest of the work; because, in order for it to have been systematic and uniform, the account of St. Paul’s ought to have been similarly preceded by a semi-theological dissertation on the Church of England, while the Law Courts might have been prefaced by an abridgement of Blackstone’s Commentaries, and a commentary on the Statutes at large.

Yet if the account of the Drama—of changes of management, of theatrical dynasties and revolutions, successes and embarrassments—has been swept away by editorial reform; something also has been added,—even more in point of quantity,—namely, the observations on Theatres, including a synoptical table showing the dimensions of some of the principal ones, and other information respecting them; all which, it is presumed, will be found quite as interesting to the architectural reader, whether professional or amateur, as was the matter it has supplanted. The chief that can be objected to it is that this Chapter is a deviation from the plan elsewhere adhered to, no other kind of buildings being similarly prefaced by remarks bearing upon them as a distinct class, with the exception of the slight observations upon English Villas by Mr. Papworth. Such is confessedly the case: but then other classes do not so much require any preliminary notice; while some of them consist of buildings so various in regard to their specific purposes, that to attempt any thing of the kind, would have been attended with extreme difficulty.

Probably no exception would have been made in favour of Theatres, was it not that what is here said on the subject of them, is offered as an indemnification for what has been retrenched. At all events, what is now substituted for the former Essay, is, as far as it goes, more in unison with the character and purpose of the work itself; and gives some information that will be new to the generality of readers. Another would probably have twaddled in pompous commonplace on the antiquity of the drama and the moral influence of the stage:—Trahit quemquem sua. In regard to the efficacy of the theatre as a school of moral instruction, the Editor leaves his readers, either to their own opinions on the subject, or to seek for opinions elsewhere; merely remarking that it is a school where many begin by learning virtue so easily, that they leave off by being accomplished in the gracefulness of Easy Virtue. Had he descanted ever so warmly on such a topic, hardly would the sympathies of architectural readers have accompanied him.

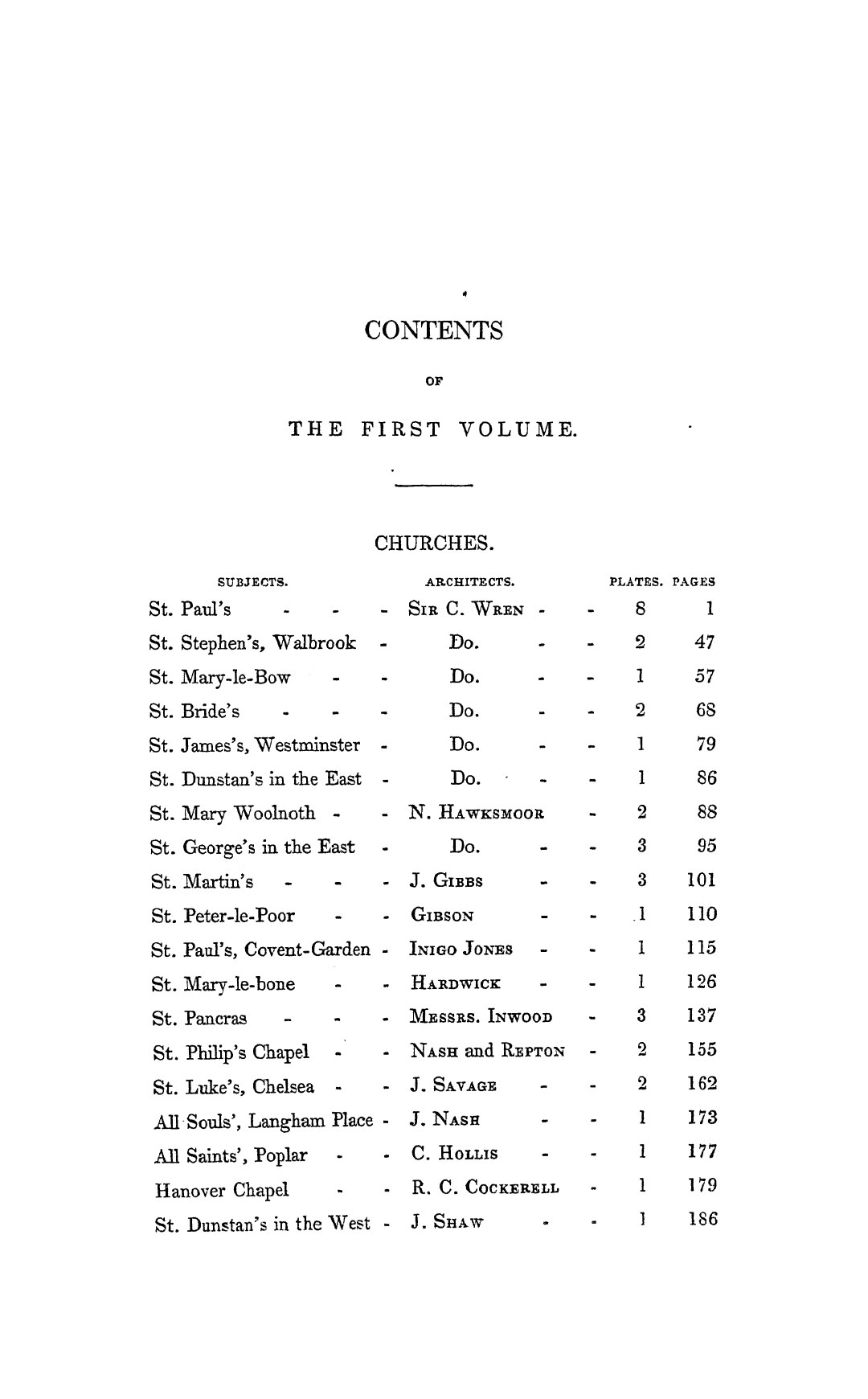

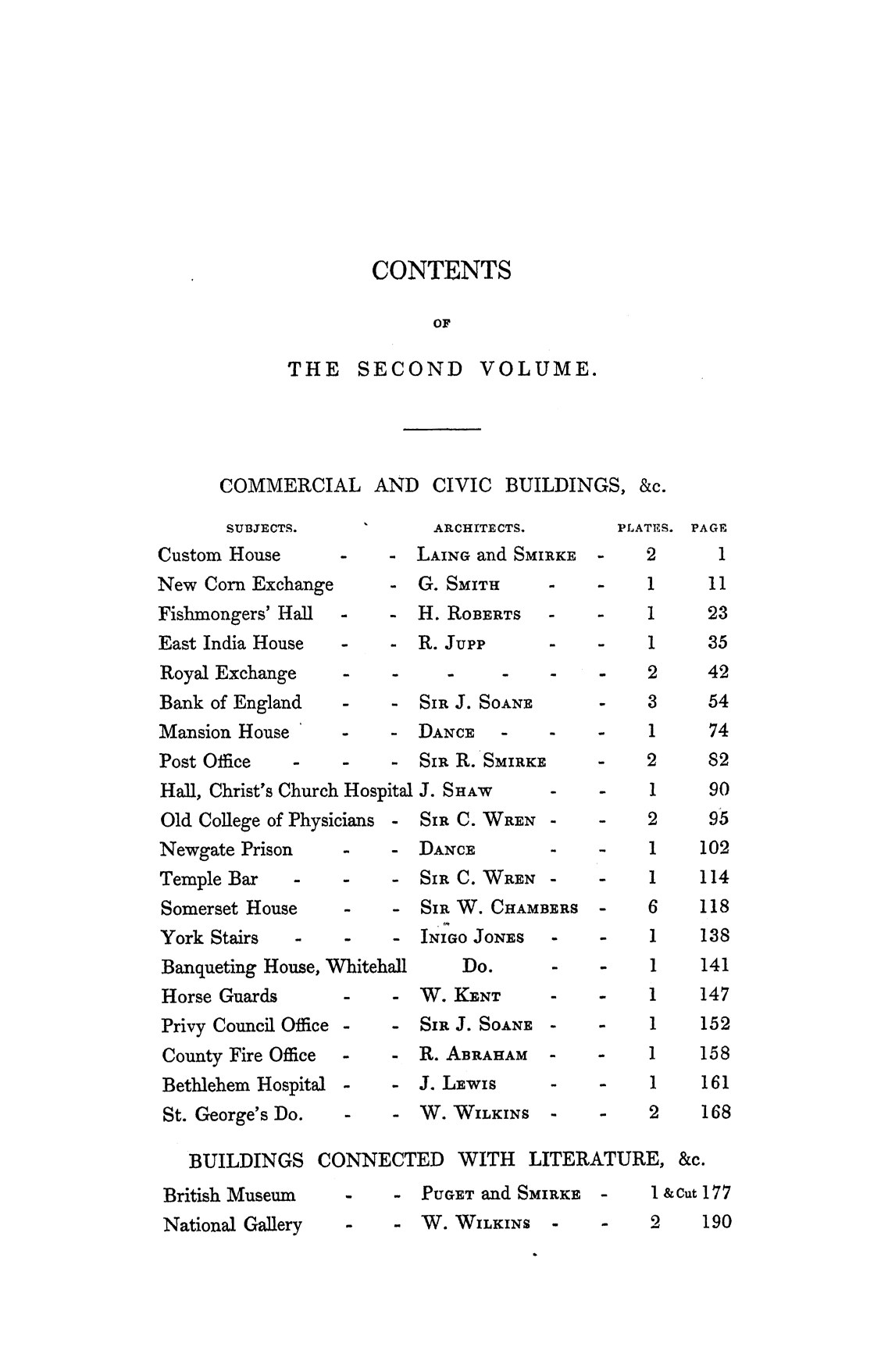

One unquestionable improvement upon the first edition is, that instead of the subjects being mixed together, without any attempt at arrangement, they are now classified under the respective heads of, I. Churches; II. Theatres; III. Commercial and Civic Buildings; IV. Buildings connected with Literature and Art, &c.; V. Palaces and Private Mansions; VI. Bridges.

In regard to the first two classes and the last, there was very little difficulty, except that occasioned by its being considered most eligible to commence with St. Paul’s, and that being done, to proceed with the other modern churches, reserving the Temple Church and Westminster Abbey till the last. It was further deemed advisable to introduce Westminster Hall, and the two subjects which form a portion of the same general mass of building, immediately after the Abbey; such arrangement being in some degree justified by their locality, while it obviated the difficulty that would have attended placing them elsewhere. Westminster Hall, therefore, and the buildings connected with it, must be considered as a kind of appendix to the account of the Abbey.

In addition to the general classification now adopted, chronological order has been in some degree observed, and the works of the same architect, when belonging to the same class, (as Wren’s churches), have been placed together. The third, fourth, and fifth divisions, are so miscellaneous as hardly to admit of precise arrangement, on which account the only order attempted in regard to the first-mentioned, is that of their situation in the course from east to west.

As every one of the buildings now added to the original subjects is of quite recent date, no history as yet attaches to them; a circumstance the Editor is far from regretting, because the respective accounts are now necessarily confined to remarks on the buildings themselves; whereas, when History and Architecture sit down to make a meal together, the latter gets very little more than the crumbs which fall from the table, while poor Criticism is fairly kicked under it, as if unworthy even to show her face. In the preface to his Geschichte der Kunst, Winckelmann gives us an anecdote to the purpose, of a writer who filled what professed to be an account of two statues of captive barbarian kings, with a history of Numidia !

The excuse that is frequently made for the reticence of criticism in regard to buildings is, that they speak sufficiently clearly for themselves; and so they certainly do, provided they are adequately illustrated by explanatory engravings; yet even then only to those who are familiar with the language they make use of, and merely as relates to them as objects. What is plainly exhibited to the eye in an engraving, of course requires not to be described in words also; consequently whenever an elevation of a building is given, it is mere repetition and reiteration to point out seriatim the parts of which it is composed: yet it does not exactly follow that there is likewise no occasion for critical comment and remark; on the contrary, these latter are then most of all serviceable when that which is the subject of them is clearly understood. Whatever, too, they may happen to he in themselves, such remarks have at least this beneficial tendency, that they serve to fix attention upon much which would else be passed over without observation; consequently, if erroneous, at least they direct notice to those points which may be reconsidered by others, and treated by them with greater diligence and acumen. Another and not the least advantage attending criticism of this sort is, that it teaches people to think and judge, and shows them how much there is to be observed and attended to in order to do so properly. Besides all which, it invests the subject with that interest which should belong to it in common with the other fine arts, but which has hitherto been kept almost entirely out of sight. It may mainly be ascribed to this last-mentioned circumstance that, as a study, architecture has so very few votaries beyond its professional pale,—so very few lay-students who apply themselves to it merely for the sake of the intellectual gratification it is capable of affording. Most persons have taken up with the notion that it is impossible to attain any adequate knowledge of the art without becoming familiar with all its mechanical and practical operations also; which is about as extravagant as it would be to fancy that a man must have handled the chisel or pencil himself, and be well acquainted with all the processes and arcana of the statuary’s workshop and the artist’s painting room, before he can judge of or relish the productions of sculpture and painting. In short, if they cared to be consistent, they would go a step further, and boldly deny at once that architecture is a fine art at all, putting it upon the same footing with those subsidiary arts of decoration which minister to architecture itself. Another prevalent prejudice against the study is, that every thing in it depends so entirely upon rules, is so fixed and hemmed in by them, as to afford no room whatever for the exercise of criticism, any more than does the plain fact that two and two make four.

Without inquiring whether these prejudices and misconceptions are not, in some degree, attributable to the course pursued by professional writers on architecture, who have very rarely, if ever, condescended to accommodate their writings to the general reader; it is sufficient to remark, that none have greater cause to lament the popular ignorance in regard to the art, which has been fostered by those prejudices, than architects themselves. While it leaves them scarcely any competent judges but their rivals, it places them at the mercy of the self-willed, the obstinate, and the capricious. On the other hand, the public are quite as much at the mercy of pretenders in the profession. It is in vain for people to demand excellence, so long as they admit that they are incompetent to discriminate between talent and no talent,—in short, do not understand either the beauties or defects of an architectural composition. Thus, although their interest and object ought to be the same, both parties mutually accuse each other.

Such a state of things is not a little injurious to the best interests of architecture itself. And architects ought by this time to have discovered, that the better informed the public in general are in respect to their art, so much the better both for that and for themselves. In proportion as architectural topics can be made to engage general attention, and rendered matter of conversation and discussion in society, so will the public take a livelier and more extended concern in the art. In this respect something has been done of late years by the establishment of the ‘Architectural Magazine,’ which there is every reason to suppose has been the means of leading many to direct their attention to a study which, if rationally pursued, is not without its allurements for others besides professional men.

More recently another periodical has appeared, entitled ‘The Civil Engineer and Architect’s Journal,’ which, in conformity with its title, devotes itself more particularly to strictly technical and practical matters, yet by no means to the exclusion of more popular subjects. Both these publications have already effected some good in disseminating a taste for such studies, and in diffusing more enlarged and liberal views in respect to the aesthetic principles of architecture, than have hitherto prevailed.

How far the Editor’s own criticisms, here offered to the public, satisfactorily exemplify what he recommends, must be left to the reader to determine. At all events, they are in no very great danger of being found fault with on the score of not entering sufficiently into details, or of being too dry and formal. Leaving alone what may be thought of many of the opinions and remarks they contain, they will strike different persons very differently, because some will relish them all the better for that, on account of which others will probably object to them. The writer who attempts to accommodate himself to the particular taste of every one, will please no one; whereas he who satisfies himself, will at all events have the luck of pleasing some one, and be apt to write naturally, if not originally. Undoubtedly there are several things both in the notes and elsewhere, that might have been omitted without causing any hiatus. Still the Editor offers no apology either for those, or any thing else he has said; considering all such apologies to be not only unavailing, but most transparently hypocritical into the bargain.

Should what has been done be found to give satisfaction, the Editor will most probably resume his task, it being in contemplation to carry on the work by at least one additional volume; yet further than that probability is at present in favour of this being done, no assurance is here given—no positive promise made, because the performance of it will in a considerable degree depend upon the reception that shall be given to the two now published. It may, however, be stated, that should such continuation of the Public Edifices be undertaken, as it will virtually become a new series, whether so entitled or not, an opportunity will be afforded for getting rid of some of the defects attending the original plan of the work, and now only partially extirpated; and also for some improvements in respect to the plates. In which case, it is probable, that in regard to one or two of the buildings now inserted, additional information will be given in more detailed and explanatory engravings.

Not only is there already an abundance of entirely fresh subjects for the continuation of the work to double its present extent, especially if they were more fully developed by drawings, but every year will add something to the stock. The new Houses of Parliament, Royal Exchange, Reform Club, and the façade of the British Museum, will doubtless prove very important architectural acquisitions to the metropolis. Perhaps, too, the buildings of the West of London Cemetery, and of the Botanic Garden about to be formed in the inner circle of the Regent’s Park, will deserve to be ranked among our public embellishments.

Among the designs that have actually been carried into execution, may be mentioned the Doric Propyleum to the London and Birmingham Railway, in Euston Square, by Hardwick; the London and Westminster Bank, Lothbury, by Cockerell and Tite; the Junior University Club House, by Smirke; the School for the Indigent Blind, by Newman; and the interior of the Synagogue, St. Helen’s Place, by Davies. But although several churches have been erected in various parts of the town and its suburbs, since that of St. Dunstan’s in the West, there is hardly one that recommends itself as an architectural subject. One of the best, at least in regard to its exterior, is that by Penne-thorne, in Gray’s Inn Road; for although small, it possesses some originality, as well as consistency of style and character,—and so far is greatly preferable to those mawkish pseudo-Grecian structures, compounded of a portico and meeting-house stuck together : the one in question, however, would have been materially improved had the curved screen walls been carried up so high as to shut out the view of the sides; had which been done, the façade would have acquired much greater importance. There is also a church in the Gothic style, now erecting from the designs of Mr. Blore, on the north side of Berwick Street, Soho, which promises to be greatly better than any thing of that sort which has been done in the metropolis for several years.

Even when all the available materials shall have been exhausted as regards the metropolis itself, there would still remain a new and ample stock for a similar—or companion work to the present one, illustrative of the Provincial Architecture of England, as exemplified in the public buildings at Liverpool, Manchester, Newcastle, Birmingham, and other principal towns. Such, for instance, as the Royal Institution, and the Athenaeum, at Manchester, and Free Grammar School, at Birmingham, (all by Mr. Barry); the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, by Mr. Basevi; the Public Libraries of that University, by Mr. Cockerell; the Victoria Rooms, Bristol, by Mr. C. Dyer; and the Athenaeum, at Derby; which last-mentioned structure is now in progress from the designs of Mr. R. Wallace.

As the field would be so extensive, such a work ought to be confined to the very best specimens, and to such as are unedited. The idea of a work of the above description, however, itself belongs to that species of architecture denominated “castle building,” it being as yet matter of doubt whether the plan here hinted at will be acted upon.

To speak, by way of conclusion, respecting his own share in the present volumes, it will be evident enough that the Editor has not scrupled to impugn many veteris mendacia famæ, and to indulge in some observations that can hardly fail to shock what the author quoted on the title page calls the ‘orthodoxy of pedantry.’ Yet if not uniformly in accordance with those commonly received,—if they occasionally tread too sharply on the heels of prejudices,—if, moreover, some of them shall be convicted of being erroneous, as well as unpalatable, the opinions here put forth by him may at least claim the merit of being independent and unborrowed. He may also be allowed to say, that in the articles now added by himself, he has endeavoured, as far as the subjects themselves afforded scope for doing so, to invest description and criticism of this kind with some degree of interest, by impartially pointing out both merits and defects, and by calling attention to particulars, which, more frequently than not, are passed over altogether. If, therefore, in some instances praise and censure nearly balance each other, that circumstance argues no inconsistency in him, whatever it may do in respect to the buildings so spoken of.

To solicit indulgence for what he has said, would be but the paltry affectation of modesty, equally unavailing and misplaced. If the remarks here submitted to that class of the public who, it is presumed, are quite competent to appreciate them, shall be found valueless, they will be treated accordingly: should they, on the contrary, possess any merit, they will ultimately make their way with the majority of readers, that is, supposing they obtain any; for as the work will be purchased chiefly for the sake of the plates, it is possible that many will examine it no further. In which case all that is here said becomes superfluous, and this Preface may be dismissed at once without another syllable.

CONTENTS of THE FIRST VOLUMECONTENTS of THE SECOND VOLUME

Sample pages

Download link (2d edition, volume 1) (pdf, yandexdisk; 51,8 MB).

Download link (2d edition, volume 2) (pdf, yandexdisk; 65,3 MB).

Download link (1st edition, volume 1) (pdf, yandexdisk; 128 MB).

Download link (1st edition, volume 2) (pdf, yandexdisk; 142 MB).

13 октября 2018, 19:42

0 комментариев

|

Партнёры

|

Комментарии

Добавить комментарий