|

|

Russian Art of the Avant-Garde Theory and Criticism : 1902—1934 / Edited and Translated by John E. Bowlt. — New York, 1976  Russian Art of the Avant-Garde Theory and Criticism : 1902—1934 / Edited and Translated by John E. Bowlt. — New York : The Viking Press, 1976. — XL, 360 p., ill. — (The Documents of 20th-century art). — ISBN 0-670-61257-X.

John E. Bowlt is Professor of Slavic Languages and Literatures at the University of Southern California, and Director of its Institute of Modern Russian Culture. He is the recipient of numerous awards and scholarships, including the Woodrow Wilson National Fellowship and the Fulbright-Hays Awards.

During the first third of the twentieth century, Russian art went through a series of dramatic changes, reflecting the political and social upheavals of the country and producing a body of influential avant-garde work.

Although the revolutionary years saw much support for the new art and its application to graphic and industrial design, many artists felt the increasingly oppressive political attitudes and left for Western Europe. Kandinsky, Malevich, Gabo, Pevsner, and others are well known for their important contribution to the history of modern Western art, but there were many lesser-known artists whose statements have never been read outside their own country.

Here John E. Bowlt has collected and translated manifestos, articles, and declarations by the principal artists and critics of the Russian avant-garde. Illustrated with more than 100 rare photographs of artworks and written works as well as facsimiles, and supplemented by clear introductory essays, bibliographical information, and copious notes, this is the essential sourcebook for a full understanding of the motivations and struggles that produced an extraordinary, seminal epoch in Russian art.

Preface

This collection of published statements by Russian artists and critics is intended to fill a considerable gap in our general knowledge of the ideas and theories peculiar to modernist Russian art, particularly within the context of painting. Although monographs that present the general chronological framework of the Russian avant-garde are available, most observers have comparatively little idea of the principal theoretical intentions of such movements as symbolism, neoprimitivism, rayonism, and constructivism. In general, the aim of this volume is to present an account of the Russian avant-garde by artists themselves in as lucid and as balanced a way as possible. While most of the essays of Vasilii Kandinsky and Kazimir Malevich have already been translated into English, the statements of Mikhail Larionov, Natalya Goncharova, and such little-known but vital figures as Vladimir Markov and Aleksandr Shevchenko have remained inaccessible to the wider public either in Russian or in English. A similar situation has prevailed with regard to the Revolutionary period, when such eminent critics and artists as Anatolii Lunacharsky, Nikolai Punin, and David Shterenberg were in the forefront of artistic ideas. The translations offered here will, it is hoped, act as an elucidation of, and commentary on, some of the problems encountered within early twentieth-century Russian art.

The task of selection was a difficult one—not because of a scarcity of relevant material, but on the contrary, because of an abundance, especially with regard to the Revolutionary period. In this respect certain criteria were observed during the process of selection: whether a given text served as a definitive policy statement or declaration of intent; whether the text was written by a member or sympathizer of the group or movement in question; whether the text facilitates our general understanding of important junctures within the avant-garde. Ultimately, the selection was affected by whether translation of a given text was available in English, although such previously translated statements as Malevich’s "From Cubism and Futurism to Suprematism" and Naum Gabo and Anton Pevsner’s "Realistic Manifesto" have been deemed too important to exclude. In some cases, specifically in those of the symbolists and the "French" faction of the Knave of Diamonds, no group declaration was issued so that recourse was made to less direct, but still significant pronouncements.

Categorization presented a problem since some statements, such as David Burliuk’s "The Voice of an Impressionist" or El Lissitzky’s "Suprematism in World Reconstruction," are relevant to more than one chronological or ideological section. Similarly, the choice of part titles cannot be entirely satisfactory. In the context of Part III, for example, it might be argued that Olga Rozanova, in "The Bases of the New Creation," was not advocating a completely "abstract" art (as her own contemporaneous painting indicated) and was merely developing the ideas of Nikolai Kulbin and Vladimir Markov; but it was precisely because of such a legitimate objection that the term "nonobjective" rather than "abstract" or "nonrepresentational" was selected, i.e., it denotes not only the latter qualities but also the idea of the "subjective," which, in the context of Rozanova and Malevich, is of vital importance. Again, the inclusion of Pavel Filonov in the final part rather than in an earlier one might provoke criticism, but Filonov was one of the few members of the Russian avant-garde to maintain his original principles throughout the 1930s—and hence his stand against the imposition of a more conventional art form was a conclusive and symbolic gesture.

Unfortunately, many of the artists included here did not write gracefully or clearly, and David Burliuk and Malevich, notably, tended to ignore the laws of syntax and of punctuation. As the critic Sergei Makovsky remarked wryly in 1913: "they imagine themselves to be writers but possess no qualifications for this." However, in most cases the temptation to correct their grammatical oversights has been resisted, even when the original was marked by ambiguity or semantic obscurity.

Since this book is meant to serve as a documentary source and not as a general historical survey, adequate space has been given to the bibliography in order that scholars may both place a given statement within its general chronological and ideological framework and pursue ideas germane to it in a more detailed fashion. In this connection, it will be of interest to note that photocopies of the original texts have been deposited in the Library of The Museum of Modem Art, New York.

Apart from the rendition of the Russian soft and hard signs, which have been omitted, the transliteration system is that used by the journal Soviet Studies, published by the University of Glasgow, although where a variant has already been established (e.g., Benois, not Benua; Burliuk, not Burlyuk; Exter, not Ekster), it has been maintained. Occasionally an author has made reference to something irrelevant to the question in hand or has compiled a list of names or titles; where such passages add nothing to the general discussion, they have been omitted, although both minor and major omissions have in every case been designated by ellipses. Dates refer to time of publication, unless the actual text was delivered as a formal lecture before publication. Wherever possible, both year and month of publication have been given. In the case of most books, this has been determined by reference to Knizhnaya letopis [Book Chronicle; bibl. RII; designated in the text by KL]; unless other reliable published sources have provided a more feasible alternative, the data in Knizhnaya letopis have been presumed correct.

Many artists, scholars, and collectors have rendered invaluable assistance in this undertaking. In particular I would like to acknowledge my debt to the following persons: Mr. Troels Andersen; Mrs. Celia Ascher; Mr. Alfred Barr, Jr.; Mr. Herman Berninger; Dr. Milka Bliznakov; Miss Sarah Bodine; Mr. and Mrs. Nicholas Burliuk; Miss Mary Chamot; Lord Chernian; Professor Reginald Christian; Mr. George Costakis; Mrs. Charlotte Douglas; Mr. and Mrs. Eric Estorick; Mr. Mark Etkind; Sir Naum Gabo; Mr. Evgenii Gunst; Mrs. Larissa Haskell; Mr. and Mrs. Leonard Hutton; Mme. Nina Kandinsky; Mme. Alexandra Larionov; Mr. and Mrs. Nikita Lobanov; Professor Vladimir Markov; M. Alexandre Polonski; Mr. Yakov Rubinstein; Dr. Aleksandr Rusakov and Dr. Anna Rusakova; Dr. Dmitrii Sarabyanov; Dr. Aleksei Savinov; Mr. and Mrs. Alan Smith; Mme. Anna Tcherkessova-Benois; Mr. Thomas Whitney. Due recognition must also go to M. Andrei B. Naglov, whose frivolous pedantries have provided a constant source of amusement and diversion.

I am also grateful to the directors and staff of the following institutions for allowing me to examine bibliographical and visual materials: British Museum, London; Courtauld Institute, London; Lenin Library, Moscow; Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.; Museum of Modern Art, New York; New York Public Library; Radio Times Hulton Picture Library, London; Royal Institute of British Architects, London; Russian Museum, Leningrad; School of Slavonic and East European Studies, University of London; Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York; Sotheby and Co., London; Taylor Institute, Oxford; Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow; Victoria and Albert Museum, London; Widener Library, Harvard.

Last but not least I would like to extend my gratitude and appreciation to my two editors, Barbara Burn and Phyllis Freeman, for without their patience, care, and unfailing cooperation this book would not have been possible.

JOHN E. BOWLT

Contents

Preface vii

List of Illustrations xv

Introduction xix

I. The Subjective Aesthetic: Symbolism and the Intuitive

Aleksandr Benois: History of Russian Painting in the Nineteenth Century [Conclusion], 1902 3

[Nikolai Ryabushinsky]: Preface to The Golden Fleece, 1906 6

David Burliuk: The Voice of an Impressionist: In Defense of Painting [Extract], 1908 8

Nikolai Kulbin: Free Art as the Basis of Life: Harmony and Dissonance (On Life, Death, etc.) [Extracts], 1908 11

Vasilii Kandinsky: Content and Form, 1910 17

Vladimir Markov: The Principles of the New Art, 1912 23

II. Neoprimitivism and Cubofuturism

Aleksandr Shevchenko: Neoprimitivism: Its Theory, Its Potentials, Its Achievements, 1913 41

Natalya Goncharova: Preface to Catalogue of One-Man Exhibition, 1913 54

Ivan Aksenov: On the Problem of the Contemporary State of Russian Painting [Knave of Diamonds], 1913 60

David Burliuk: Cubism (Surface—Plane), 1912 69

Natalya Goncharova: Cubism, 1912 77

Ilya Zdanevich and Mikhail Larionov: Why We Paint Ourselves: A Futurist Manifesto, 1913 79

III. Nonobjective Art

Mikhail Larionov and Natalya Goncharova: Rayonists and Futurists: A Manifesto, 1913 87

Mikhail Larionov: Rayonist Painting, 1913 91

Mikhail Larionov: Pictorial Rayonism, 1914 100

Olga Rozanova: The Bases of the New Creation and the Reasons Why It Is Misunderstood, 1913 102

Suprematist Statements, 1915:

Ivan Puni and Kseniya Boguslavskaya 112

Kazimir Malevich 113

Ivan Klyun 114

Mikhail Menkov 114

Kazimir Malevich: From Cubism and Futurism to Suprematism: The New Painterly Realism, 1915 116

Ivan Klyun: Primitives of the Twentieth Century, 1915 136

Statements from the Catalogue of the "Tenth State Exhibition: Nonobjective Creation and Suprematism," 1919:

Varvara Stepanova: Concerning My Graphics at the Exhibition 139

Varvara Stepanova: Nonobjective Creation 141

Ivan Klyun: Color Art 142

Kazimir Malevich: Suprematism 143

Mikhail Menkov 145

Lyubov Popova 146

Olga Rozanova: Extracts from Articles 148

Aleksandr Rodchenko: Rodchenko’s System 148

El Lissitzky: Suprematism in World Reconstruction, 1920 151

IV. The Revolution and Art

Natan Altman: “Futurism” and Proletarian Art, 1918 161

Komfut: Program Declaration. 1919 164

Boris Kushner: “The Divine Work of Art” (Polemics), 1919 166

Nikolai Punin: Cycle of Lectures [Extracts], 1919 170

Aleksandr Bogdanov: The Proletarian and Art, 1918 176

Aleksandr Bogdanov: The Paths of Proletarian Creation, 1920 178

Anatolii Lunacharsky and Yuvenal Slavinsky: Theses of the Art Section of Narkompros and the Central Committee of the Union of Art Workers Concerning Basic Policy in the Field of Art, 1920 182

David Shterenberg: Our Task, 1920 186

Anatolii Lunacharsky: Revolution and Art, 1920-22 190

Vasilii Kandinsky: Plan for the Physicopsychological Department of the Russian Academy of Artistic Sciences, 1923 196

Lef: Declaration: Comrades, Organizers of Life!, 1923 199

V. Constructivism and the Industrial Arts

Vladimir Tatlin: The Work Ahead of Us, 1920 205

Naum Gabo and Anton Pevsner: The Realistic Manifesto, 1920 208

Aleksei Gan: Constructivism [Extracts], 1922 214

Boris Arvatov: The Proletariat and Leftist Art, 1922 225

Viktor Pertsov: At the Junction of Art and Production, 1922 230

Statesments from the Catalogue of the "First Discussional Exhibition of Associations of Active Revolutionary Art," 1924:

Concretists 240

The Projectionist Group 240

The First Working Group of Constructivists 241

The First Working Organization of Artists 243

Osip Brik: From Pictures to Textile Prints, 1924 244

Aleksandr Rodchenko: Against the Synthetic Portrait, For the Snapshot, 1928 250

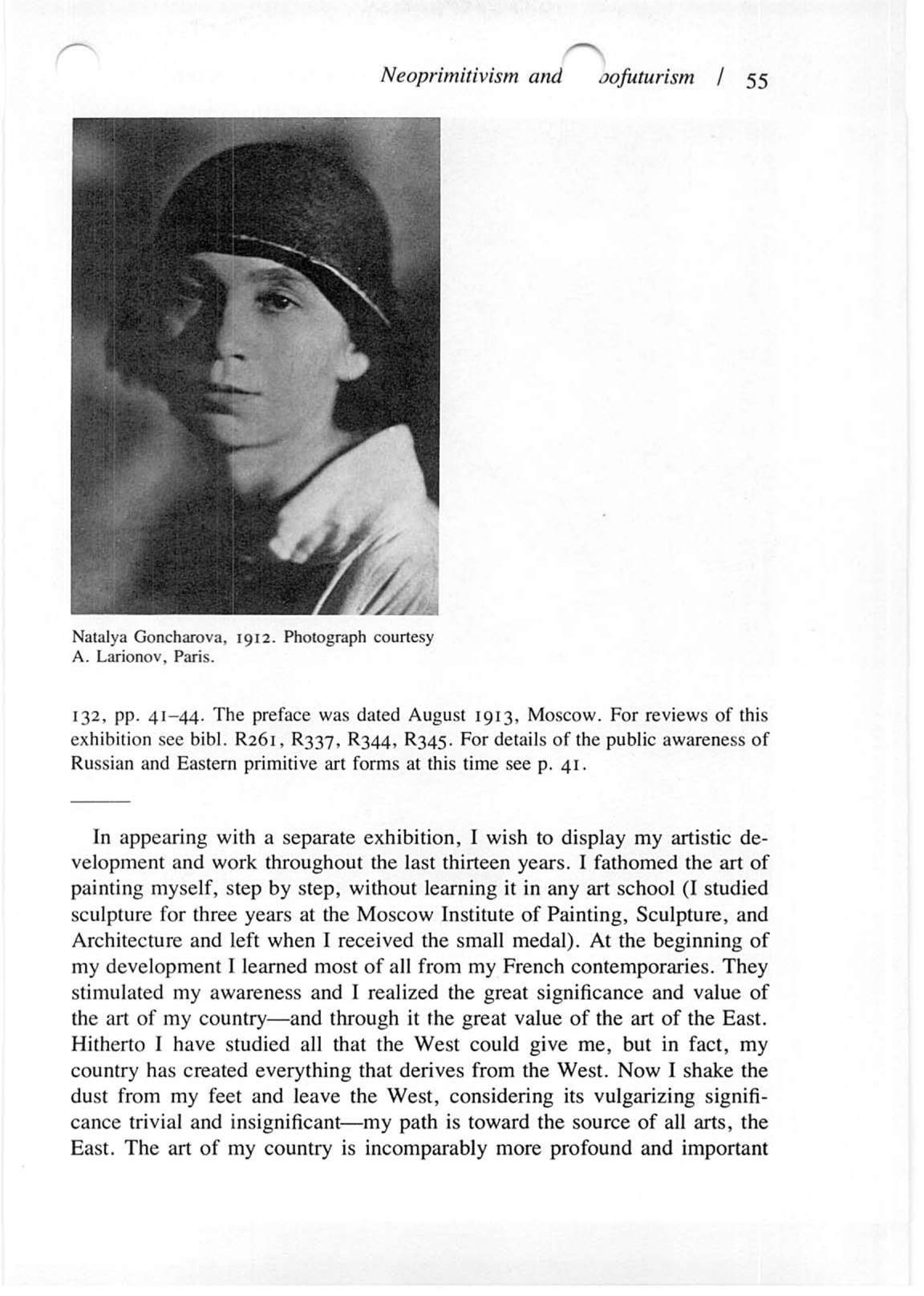

Yakov Chernikhov: The Construction of Architectural and Machine Forms [Extracts], 1931 254

VI. Toward Socialist Realism

AKhRR: Declaration of the Association of Artists of Revolutionary Russia, 1922 263

AKhRR: The Immediate Tasks of AKhRR: A Circular to All Branches of AKhRR—An Appeal to All the Artists of the U.S.S.R., 1924 268

AKhR: Declaration of the Association of Artists of the Revolution, 1928 271

October—Association of Artistic Labor: Declaration, 1928 273

OST [Society of Easel Artists]: Platform, 1929 279

Four Arts Society of Artists: Declaration, 1929 281

Pavel Filonov: Ideology of Analytical Art [Extract], 1930 284

Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks): Decree on the Reconstruction of Literary and Artistic Organizations, 1932 288

Contributions to the First All-Union Congress of Soviet Writers [Extracts], 1934:

From Andrei Zhdanov’s Speech 292

From Maxim Gorky’s Speech on Soviet Literature 294

From Igor Grabar’s Speech 295

From the First Section of the Charter of the Union of Soviet Writers of the U.S.S.R. 296

Notes 298

Notes to the Preface 298

Notes to the Introduction 298

Notes to the Texts 300

Bibliography 309

A: Works Not in Russian 309

B: Works in Russian 330

Index 349

Sample pages

Download link (pdf, yandexdisk; 19,5 MB).

Все авторские права на данный материал сохраняются за правообладателем. Электронная версия публикуется исключительно для использования в информационных, научных, учебных или культурных целях. Любое коммерческое использование запрещено. В случае возникновения вопросов в сфере авторских прав пишите по адресу 42@tehne.com.

28 июля 2018, 17:27

0 комментариев

|

Партнёры

|