|

|

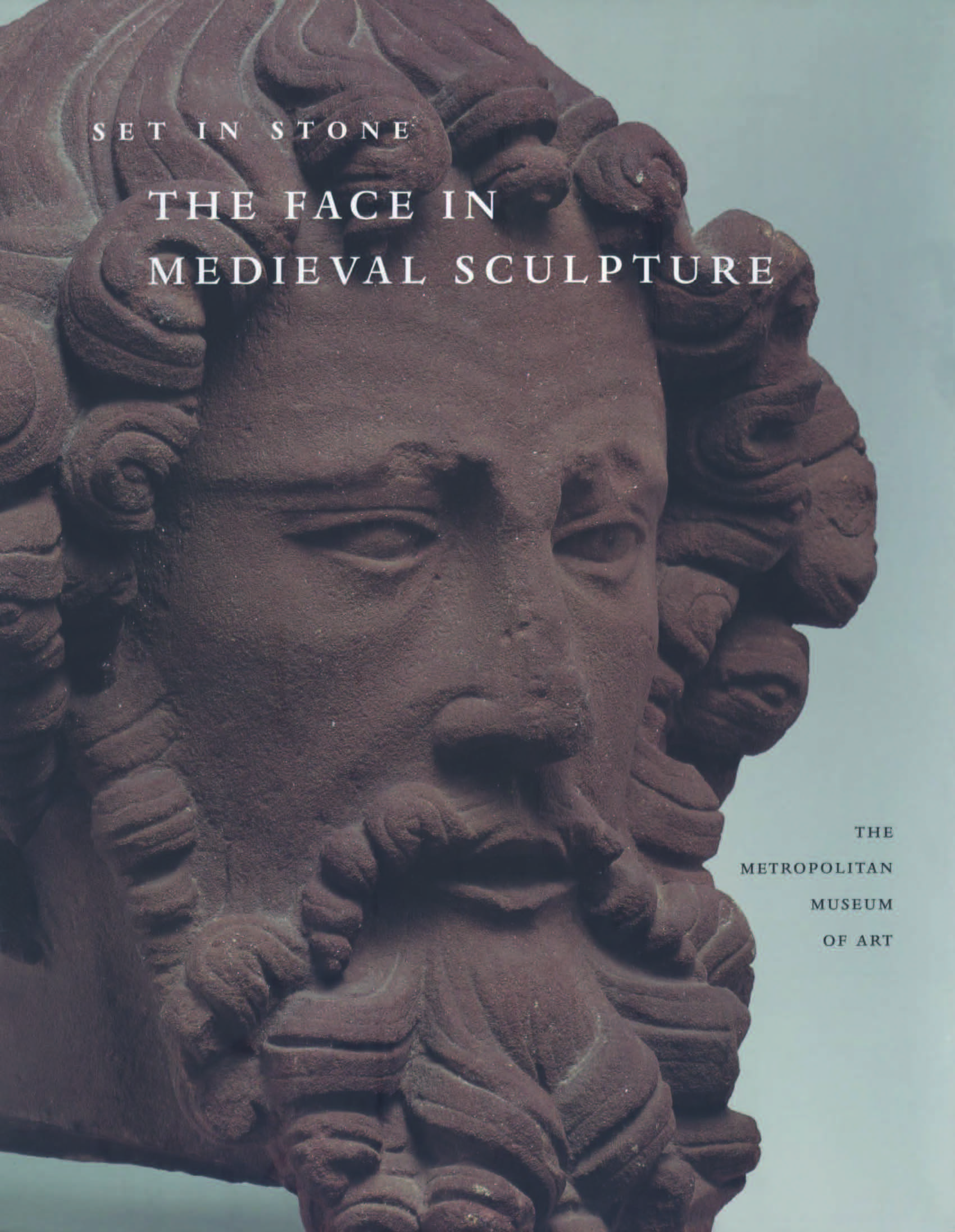

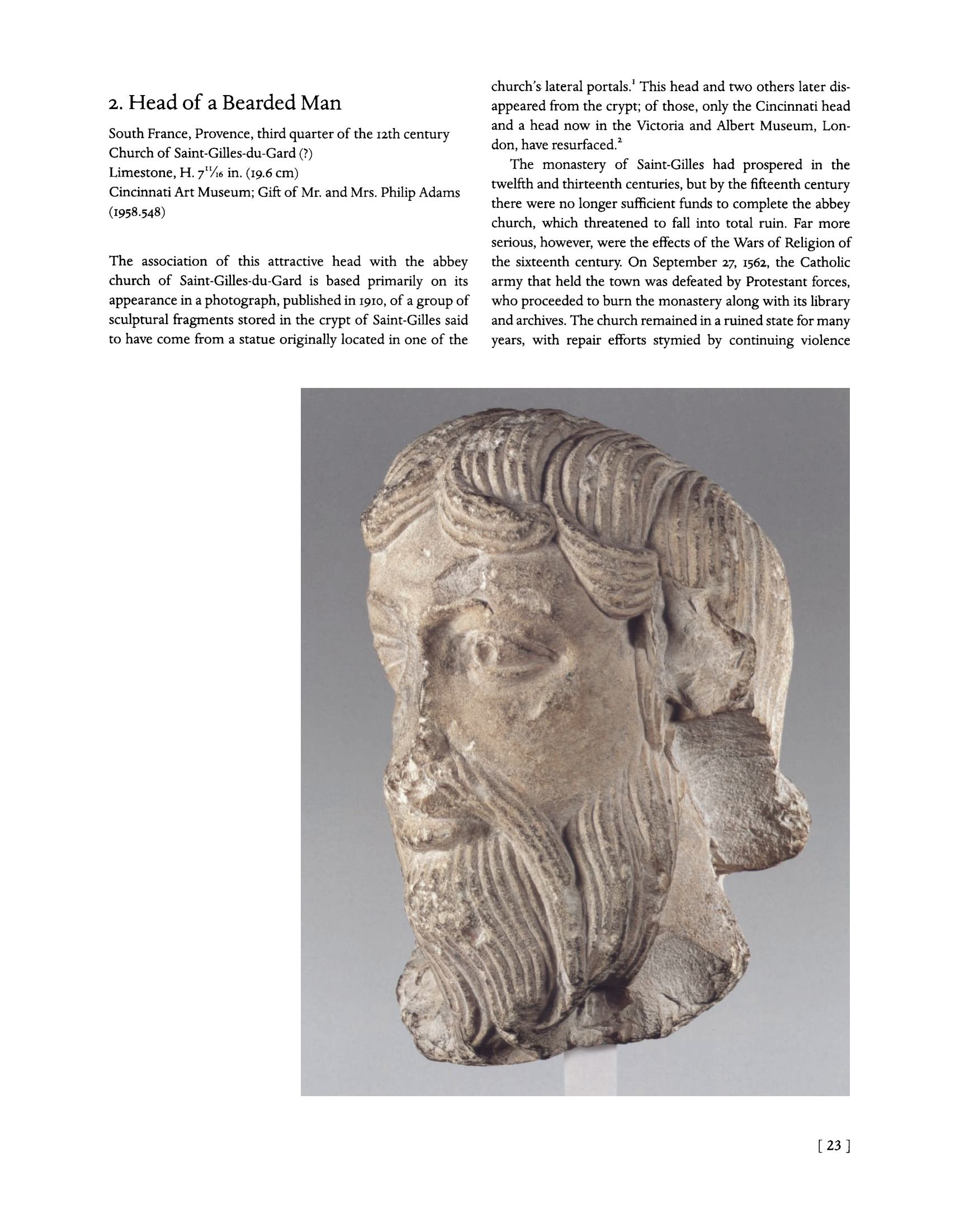

Set in Stone: The Face in Medieval Sculpture. — New York, 2006  Set in Stone: The Face in Medieval Sculpture / Edited by Charles T. Little; Including an essay by Willibald Sauerländer. — New York : The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2006. — XVI, 222 p., ill. — ISBN 1-58839-192-2

Faces in medieval sculpture are explorations of human identity, marked not only by evolving nuances of style but also by ongoing drama of European history. The eighty-one sculpted heads featured in this beautifully illustrated volume provide a sweeping view of the Middle Ages, from the waning days of the Roman Empire to the Renaissance. Each masterful sculpture bears eloquent witness to its own history, whether it was removed from its original context for ideological reasons or because of changing tastes.

As a work of art, the sculpted head is a particularly moving and vivid fragment; it often seems to retain some part of its past, becoming not unlike a living remnant of an age. In antiquity and throughout the Middle Ages it was generally believed that the soul resided in the head, as articulated by Plato in the Timaeus. The head was thus understood to be a center of power, the core of individual identity, and the primary vehicle for human expression, emotion, and character.

Many medieval sculpted heads became separated from their settings—often churches or ecclesiastical monuments—by the seemingly endless destruction and displacement of art works in Europe during and after the Middle Ages. Political and religious ferment, neglect, shifts in taste, and simply time itself: all exacted a heavy toll. During the French Revolution, in particular, legions of stone figures lost their heads in a course of mutilation that paralleled the infamous guillotine. In many cases the artistic or aesthetic merits of a given fragment are all that remain of the original work's context, meaning, and significance. Some heads survived precisely because of their innate beauty, or perhaps out of reverence for the grand monuments to which they once belonged.

Seven thematic sections retrace the history of these heads using both traditional art-historical methods, such as connoisseurship and archaeology, as well as the latest scientific technologies. In his introduction to the volume, Charles T. Little provides an overview of these general themes, which include Iconoclasm, The Stone Bible, and Portraiture. An essay by distinguished scholar Willibald Sauerländer discusses the complex and fascinating issue of physiognomy in medieval art, from menacing or carnivalesque grotesques to the beatific visages of saints and apostles. Sauerländer presciently observes, "To learn about 'the fate of the face' in the Middle Ages—a period torn by strife, faith, and fear—may prove today to be more than a mere art-historical concern."

Director's Foreword

In a museum whose holdings are as vast and diverse as those of the Metropolitan, there is always the possibility that a visitor might take for granted some of the extraordinary elements of the permanent collection. Many treasures are hidden in plain sight, as it were, on continual view in the galleries, and may thus sometimes be passed by with no or too little notice taken of them. The Museum takes seriously its primary mission of preserving and studying its permanent collection, and thus we are constantly developing new ways of kindling the public’s awareness of these diverse riches. “Set in Stone: The Face in Medieval Sculpture” brings a specific focus to our superb collection of medieval art, as it also expands on important aspects of the collection through marvelous and generous loans. This is not the Museum’s first exhibition to use the sculpted head as a theme. In 1940 an exhibition titled simply “Heads in Sculpture” drew on the Metropolitan’s holdings of works from Egypt, China, and western Europe.

In light of the chronological extent of the exhibition, which includes sculptures dating from the end of the Roman Empire to the Renaissance, the works gathered together are presented according to thematic and aesthetic criteria, rather than in chronological or geographic order, so that we may view this material through fresh eyes. While the holdings of the Department of Medieval Art and The Cloisters provide the core thread of the narrative, the story of the sculpted human face in the Middle Ages is augmented by key loans from public institutions in the United States and Europe. In particular, the exhibition affords several opportunities to reunite dispersed elements, some newly identified, from the cathedral of Notre-Dame in Paris and from the royal abbey of Saint-Denis. I wish to acknowledge the generosity of these lenders and express the Museum’s hope that the featured juxtapositions mutually enhance our appreciation of the works of art. In addition, a number of private collectors kindly agreed to lend important sculptures, and to them I express our special gratitude.

The exhibition was conceived and organized by Charles T. Little, Curator in the Department of Medieval Art and The Cloisters, who also established the intellectual foundations of its themes. He was fortunate to have the able assistance of Wendy A. Stein, Research Associate; to both of them, I offer the Museum’s heartfelt thanks. The exhibition also recognizes the fiftieth anniversary of the International Center of Medieval Art, whose offices are located at The Cloisters. This is a particularly fitting celebration of this fruitful collaboration among scholars and collectors of medieval art, many of whom have contributed to the catalogue or offered timely and most welcome advice.

Although the exhibition includes sculpture from the Early Byzantine world, England, Italy, and elsewhere, the majority of the works are French in origin and date to the Gothic period. For that reason, it is especially gratifying that the exhibition is made possible by The Florence Gould Foundation, whose commitment to French cultural awareness in America is both visionary and timely. Additional support is provided by the Michel David-Weill Fund. I want to specially acknowledge Michel David-Weill, a trustee of the Museum and chair of the Visiting Committee of the Department of Medieval Art and The Cloisters, for his enthusiasm and generosity. Finally, The Metropolitan Museum of Art is grateful to the Robert Lehman Foundation for making the Robert Lehman Wing galleries available for the exhibition.

Philippe de Montebello

Director

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

As this catalogue was going to press, new information came to light regarding the Crowned Bust of a Woman from Ravello (cat. no. 66 and the frontispiece to this volume). During examination of the sculpture in preparation for shipment to New York, the office of the Soprintendente, Salerno, ascertained that the bust is most likely a recarved Antique sculpture: an excellent example of how the study of objects loaned to exhibitions can lead directly to valuable new insights and discoveries.

Introduction: Facing the Middle Ages

Charles T. Little

“Set in stone: the face in medieval sculpture” offers a glimpse of the art of the Middle Ages that is at once narrow and extraordinarily diverse. The faces presented here are mostly fragments from monumental settings, many altered in one way or another by time, revolution, neglect, or the vicissitudes of taste. Even as fragments, however, they retain some viable part of their past—a memory or purpose if you will—and have thus become not unlike living remnants of an age. It is appropriate, then, that we should attempt to establish a dialogue with this particularly vivid type of fragment, the sculpted head, by sampling works from across the expansive and heterogeneous period known as the Middle Ages.

There is unquestionably abundant material for comparison. The heads in the exhibition span more than fifteen hundred years in date, represent a broad geographic area, and range from the highly idealized to the generalized: in short, they constitute a cross section of the era's evolving styles. Our objective was to ask new questions of these fascinating works and, in some cases, to suggest new answers. The germ of this process was the Metropolitan Museum’s exceptional collection of heads and faces in stone, metal, and wood; these core works were then complemented by crucial loans from private and public collections. Each of the eighty-one sculptures has become separated from its original context, and thus from much of its original meaning, by the seemingly endless destruction and displacement of art works in Europe during and after the Middle Ages. The French Revolution, in particular, witnessed legions of stone figures losing their heads in a systematic course of demolition that paralleled the work of the infamous guillotine. Out of this wreckage arose a new class of sculpture, the collectible object, that by the simple virtue of having survived the maelstrom of European history became integral to the genesis of collecting and exhibiting medieval art.

Many of these heads exist today as pure forms without historical context: silent witnesses to history whose artistic merits are sometimes all that remains of their original meanings and significance. In fact a good number have survived, albeit in their current mutilated states, precisely because of their innate beauty, or perhaps out of reverence for the grand monuments to which they once belonged. In attempting to retrace the history of these fragments, we find ourselves asking what sculptures of the human head can reveal to us about those who produced them, and about how those people perceived themselves.

Part of the answer lies in the fact that for millennia the head has been understood to be a center of power, the core of individual identity, and the primary vehicle for human expression, emotion, and character. In antiquity and throughout the Middle Ages, it was generally believed that the soul resides in the head, as articulated by Plato in the Timaeus (44d), where he explains that the head is dominant and divine and thus survives death: “and so in the vessel of the head, they first of all put a face in which they inserted organs to minister in all things to the providence of the soul, and the appointed part, which has authority, to be by nature the part which is in front.” Following Plato, many medieval theologians—such as Chalcidius in the fourth century and, in the twelfth century, the Scholastic philosopher William of Conches as well as the Islamic philosopher Averroës—believed that the soul resides in the head. (The other theological view, after Aristotle’s On the Soul, favored the heart.)

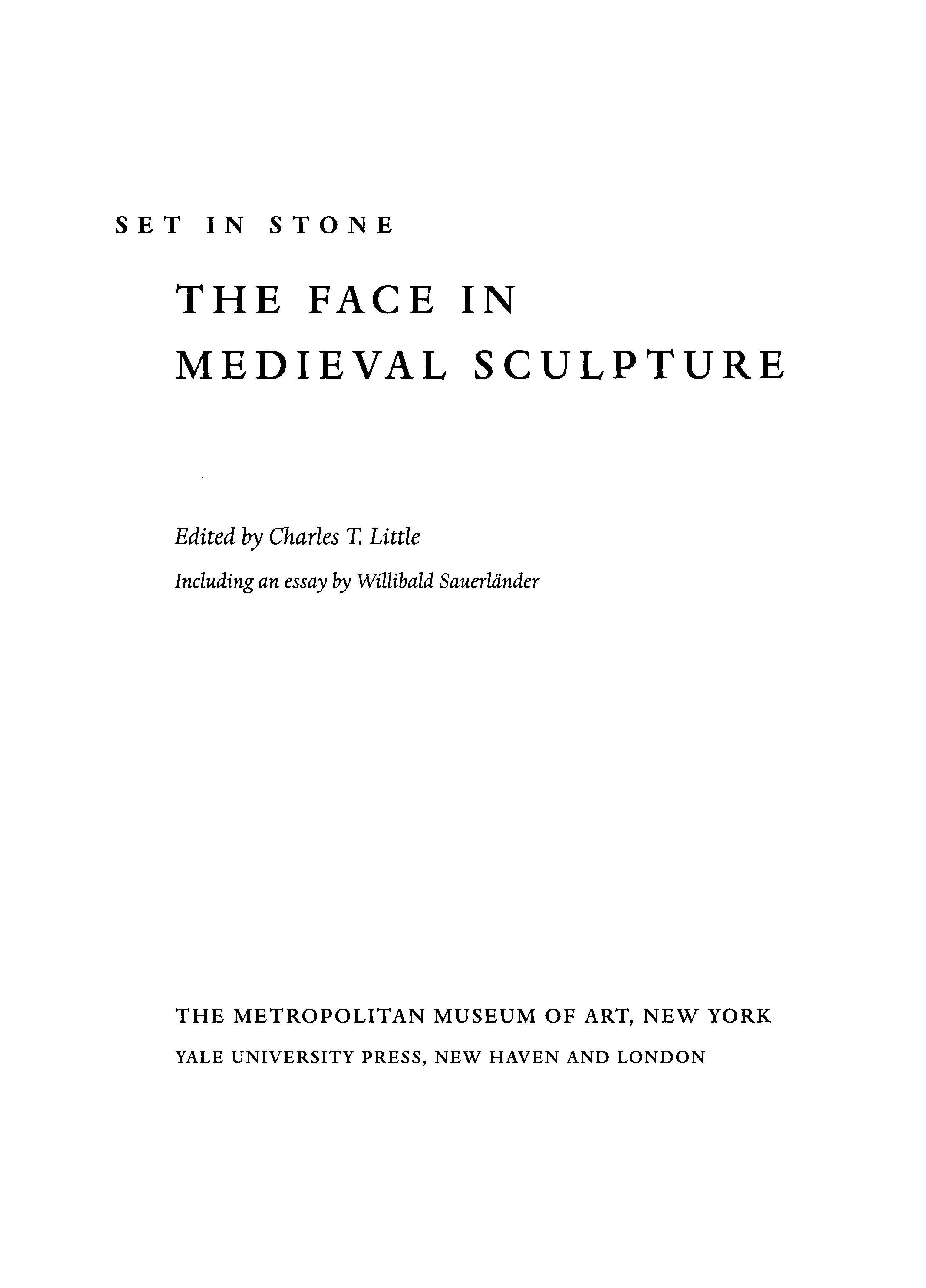

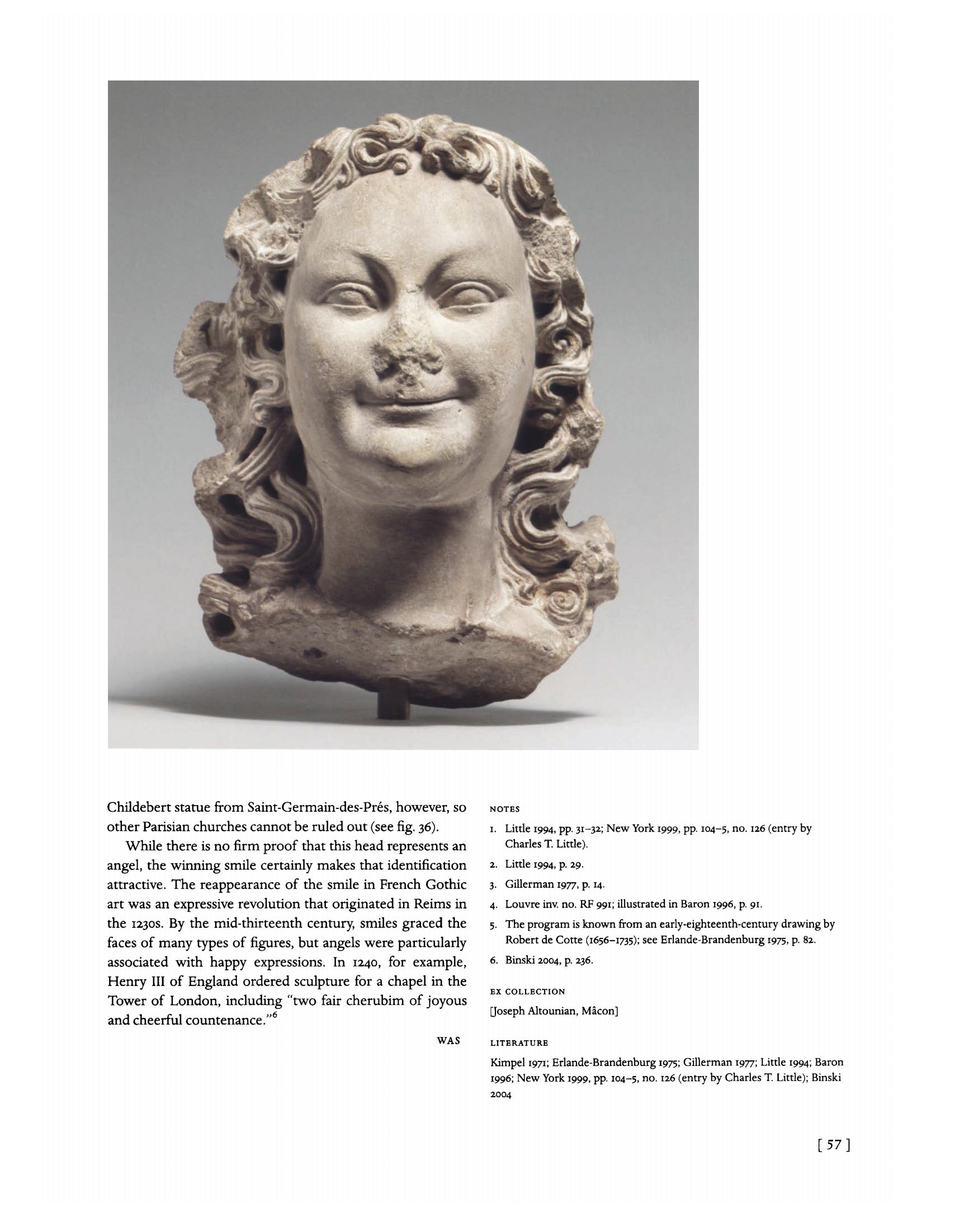

One of the striking characteristics of the heads in “Set in Stone” is that most reveal little or no expression. The complex tension between this apparent absence of emotion and the otherwise grossly distorted faces and countenances that abound in medieval art is explored in the following essay by Willibald Sauerländer. One might expect, for example, that an innocent feature such as a smile, first convincingly represented about 1200 (see cat. no. 17), would reflect the growing naturalism evident in art of the Gothic period. Yet explications of medieval physiognomy are seldom that simple, and the seeming dearth of expressivity may be linked to other concerns. One possible reason is that most of the heads belong to sculptures of holy figures (apostles, saints, or prophets) or personifications of religious concepts (the theological Virtues), and as such they may be visual representations of a serene state or transcendent happiness. “It is not right for the servant of God to show sadness and a dismal face,” Saint Francis reminds us, and indeed these heads convey a dignified aura through what at the time was a new and powerfully sculptural presence. This characteristic may have had underpinnings in some of the principal theological debates of the Gothic age. Thomas Aquinas, for instance, asks in his Summa contra Gentiles whether happiness can ever be found on earth. “The final happiness,” he proclaims in Book 3 (48:8), “will be in the knowledge of God, which the human soul has after this life...” Aquinas finds assurance in his belief in the famous passage from Saint Paul’s First Epistle to the Corinthians (13:12), “For now we see through a glass darkly; but then face to face.”

Many a conundrum greets the modern scholar seeking to investigate the ideological, cultural, artistic, and provenance questions raised by these membra disjecta, from issues of attribution and localization to meaning and date. “Set in Stone” addresses such puzzles in a variety of ways, drawing on connoisseurship, archaeology, history, and science to let the sculptures, as much as possible, tell their own stories. In order to frame these diverse topics, the exhibition has been organized into seven thematic sections.

The first is Iconoclasm, which examines the ways in which many medieval sculpted heads were violently separated from their original contexts. In addition to political upheavals such as the French Revolution, religious fervor, especially the Reformation, was often a source of ruination. We have seen in our own recent political history the dramatic power ascribed to images and the sometimes brutal force brought to bear on them because of this power, exemplified by the Taliban’s destruction of the ancient Buddhas at Bamiyan in 2001. The second theme concerns the Limestone Sculpture Provenance Project, an ongoing interdisciplinary effort that employs neutron activation analysis (NAA) to reunite fragments of limestone sculpture with their original sites. The technique was pioneered by the Metropolitan Museum in the 1970s, originally in collaboration with Brookhaven National Laboratory, Upton, New York, and now with the University of Missouri, Columbia. Because several of the sculpted heads in the exhibition come from Notre-Dame Cathedral in Paris, in some ways this section echoes the clarion call of Victor Hugo in the nineteenth century to restore and preserve Notre-Dame for the ages. It was Hugo, in his Notre-Dame de Paris (1831), who praised the cathedral, then a sad reflection of its past glory, as “a vast symphony in stone... the tremendous sum of the joint contributions of all the forces of an entire epoch.”

The third theme is the Stone Bible, a reference to the rich iconographie programs that adorn (or once adorned) medieval cathedrals and churches. Sculptures of characters from the Bible and church history were made to enact stories on such monuments, and thus in this section can be found many heads known to represent specific individuals, from Old Testament prophets and kings to apostles, the Virgin Mary, and Christ. Marginalia, the exhibition's fourth theme, examines what recent scholarship has suggested might be a counterpoint to the “official” iconographie responsibilities of the Stone Bible. Placed in high or otherwise obscure locations, these varied works—including carved architectural elements such as capitals, corbels, and misericords—inhabited the literal edges of medieval monuments, part of a seeming playground for the energized human imagination. Not necessarily considered “high” art, these occasionally cartoonlike and fanciful objects were often vehicles for formal experimentation or whimsy.

The fifth theme, Portraiture, examines how the conventions for depicting specific individuals shifted during the Middle Ages. Defined by John Pope-Hennessy in his Portrait in the Renaissance (1966) as “the depiction of an individual in his own character,” portraiture in the medieval period was, arguably, an altogether more complicated concept that challenges the sufficiency of traditional representational strategies such as likeness and verisimilitude. Gothic Italy, the sixth theme, reflects on the tenacity of the classical tradition in that country. In southern Italy, for example, rulers such as the Hohenstaufen Emperor Frederick II appropriated elements of Italy’s Roman past to enhance their own images; in other Italian regions, the prevalence of classical ruins had a more direct influence on medieval artists.

The final theme concerns sculptures that can be broadly labeled Objects of Devotion. Perhaps more than any other works in the exhibition, these pieces are imbued with an almost palpable power. In the case of Celtic votive heads, whose shadowy origins are difficult to reconstruct, this is a totemic potency. Reliquary busts, a product of the cult of the saints in the High Middle Ages, were similarly invested with great importance. Beautifully crafted from wood or metal and sometimes elaborately decorated, these busts—some of which contain fragments of the skull of the individual saint they depict (see cat. no. 78)—are evocative yet elegant testaments to the power of the head as a holy relic. The closing image illustrated in the catalogue is a poignant statue of Saint Firmin—the first bishop of Amiens, who was martyred by decollation in a.d. 287—shown holding his own head. Not without irony, then, is the opening celebration for “Set in Stone” scheduled for September 25, Saint Firmin’s feast day.

Contents

Director's Foreword by Philippe de Montebello.. vi

Statement from the International Center of Medieval Art.. viii

Acknowledgments.. ix

Contributors to the Catalogue.. xii

Lenders to the Exhibition.. xiii

Introduction: Facing the Middle Ages.. xiv

Charles T. Little

The Fate of the Face in Medieval Art.. 2

Willibald Sauerländer

Iconoclasm: A Legacy of Violence.. 18

Stephen K. Scher

CATALOGUE NUMBERS 1–12

The Limestone Project: A Scientific Detective Story.. 46

Georgia Wright and Lore L. Holmes

CATALOGUE NUMBERS 13–25

The Stone Bible: Faith in Images.. 74

Jacqueline E. Jung

CATALOGUE NUMBERS 26–37

What are Marginalia?.. 100

Janetta Rebold Benton

CATALOGUE NUMBERS 38–46

Sculpting Identity.. 120

Stephen Perkinson

CATALOGUE NUMBERS 47–61

Gothic Italy: Reflections of Antiquity.. 146

Christine Verzar and Charles T. Little

CATALOGUE NUMBERS 62–69

Reliquary Busts: "A Certain Aristocratic Eminence".. 168

Barbara Drake Boehm

CATALOGUE NUMBERS 70–81

Bibliography.. 199

Index.. 213

Sample pages

Download link (pdf, yandexdisk; 34,7 MB).

13 марта 2020, 20:29

0 комментариев

|

Партнёры

|

Комментарии

Добавить комментарий