|

|

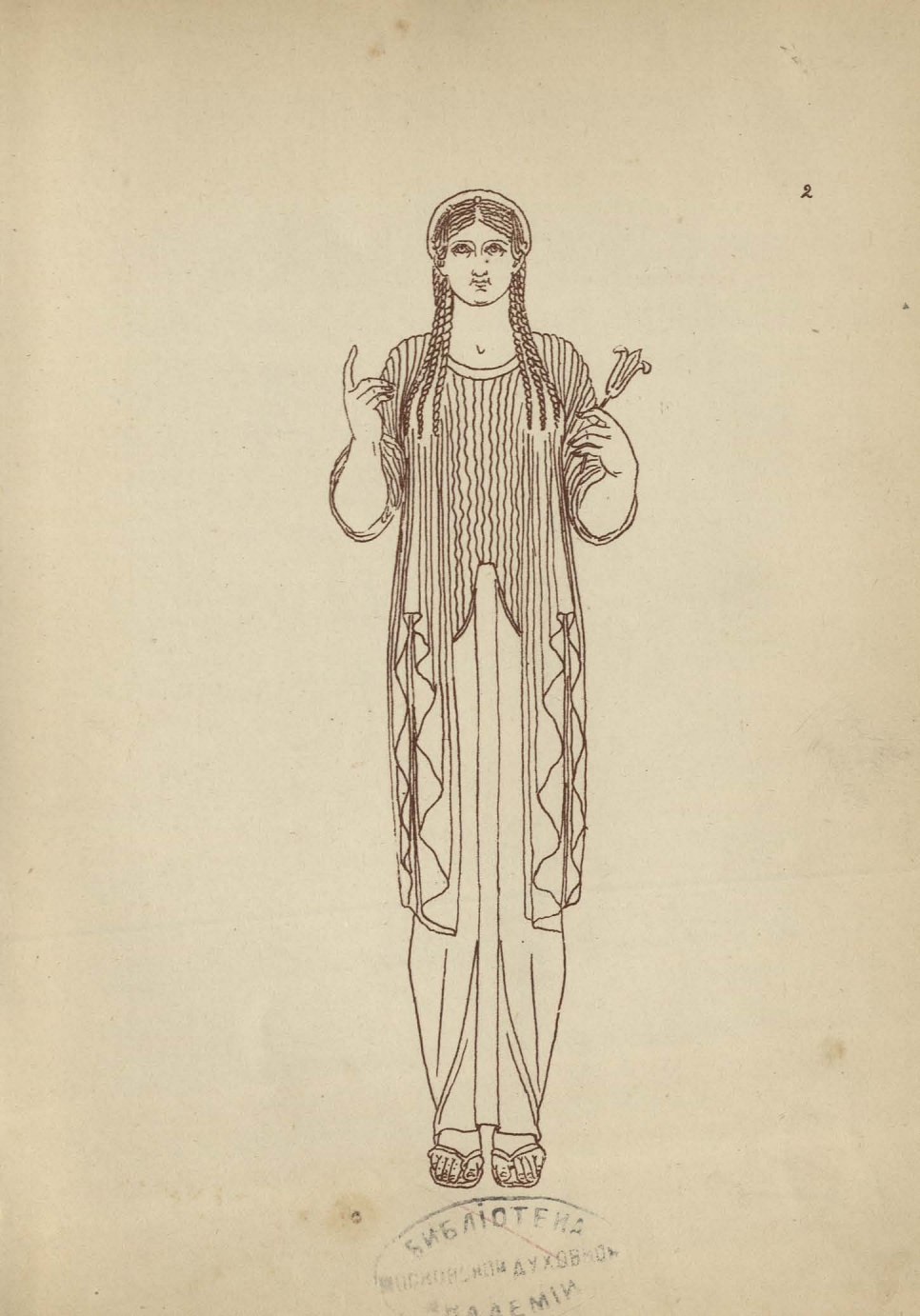

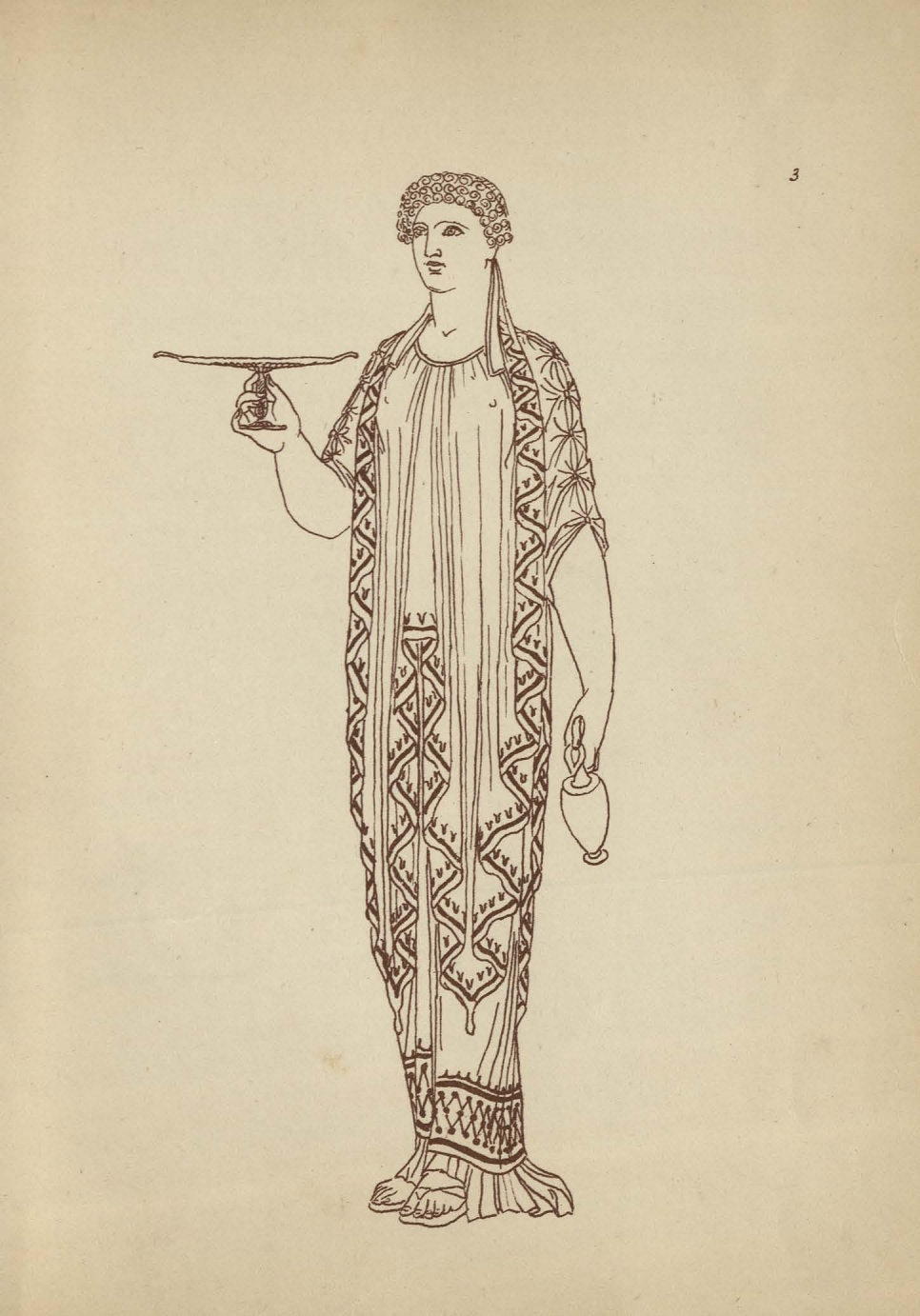

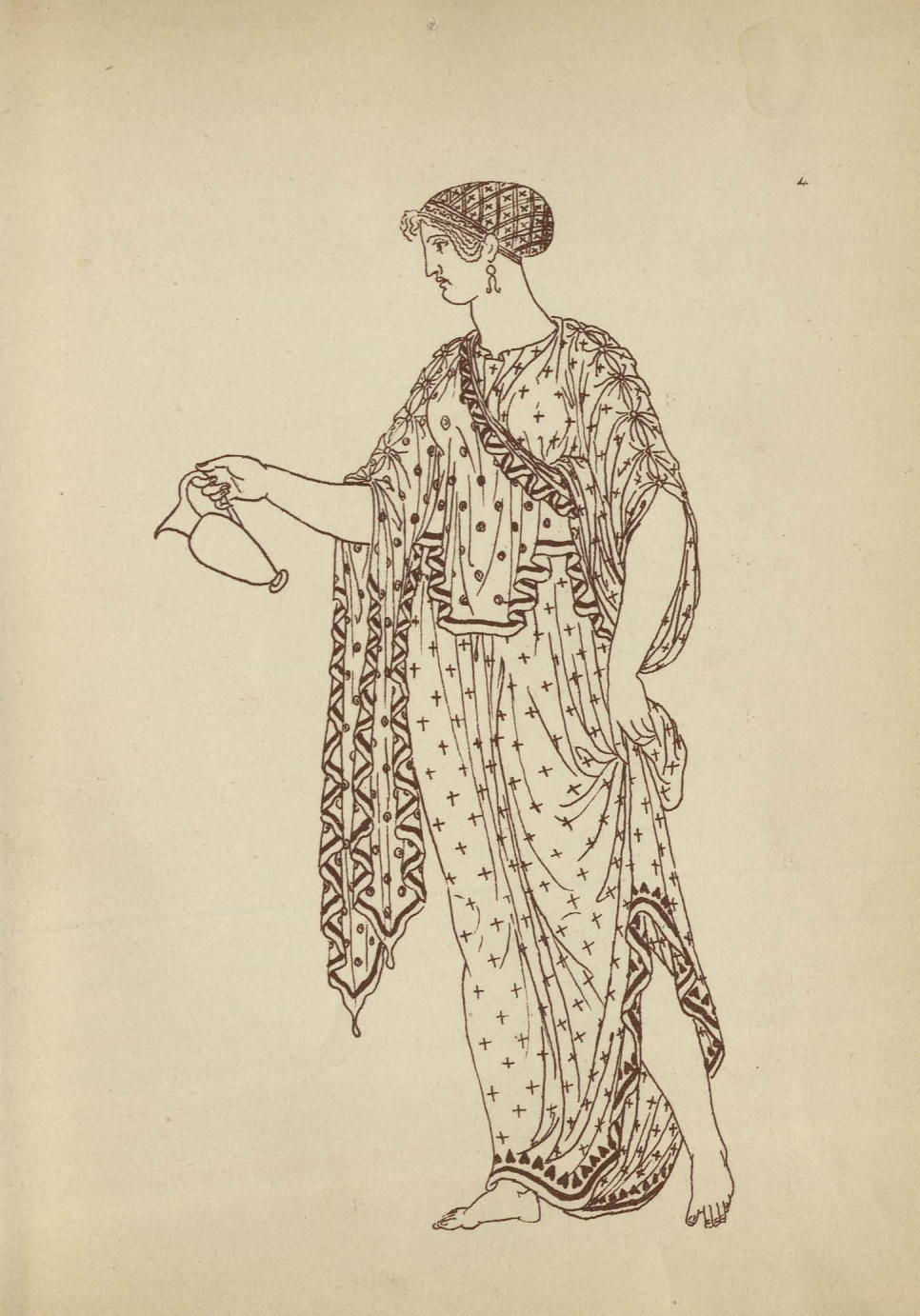

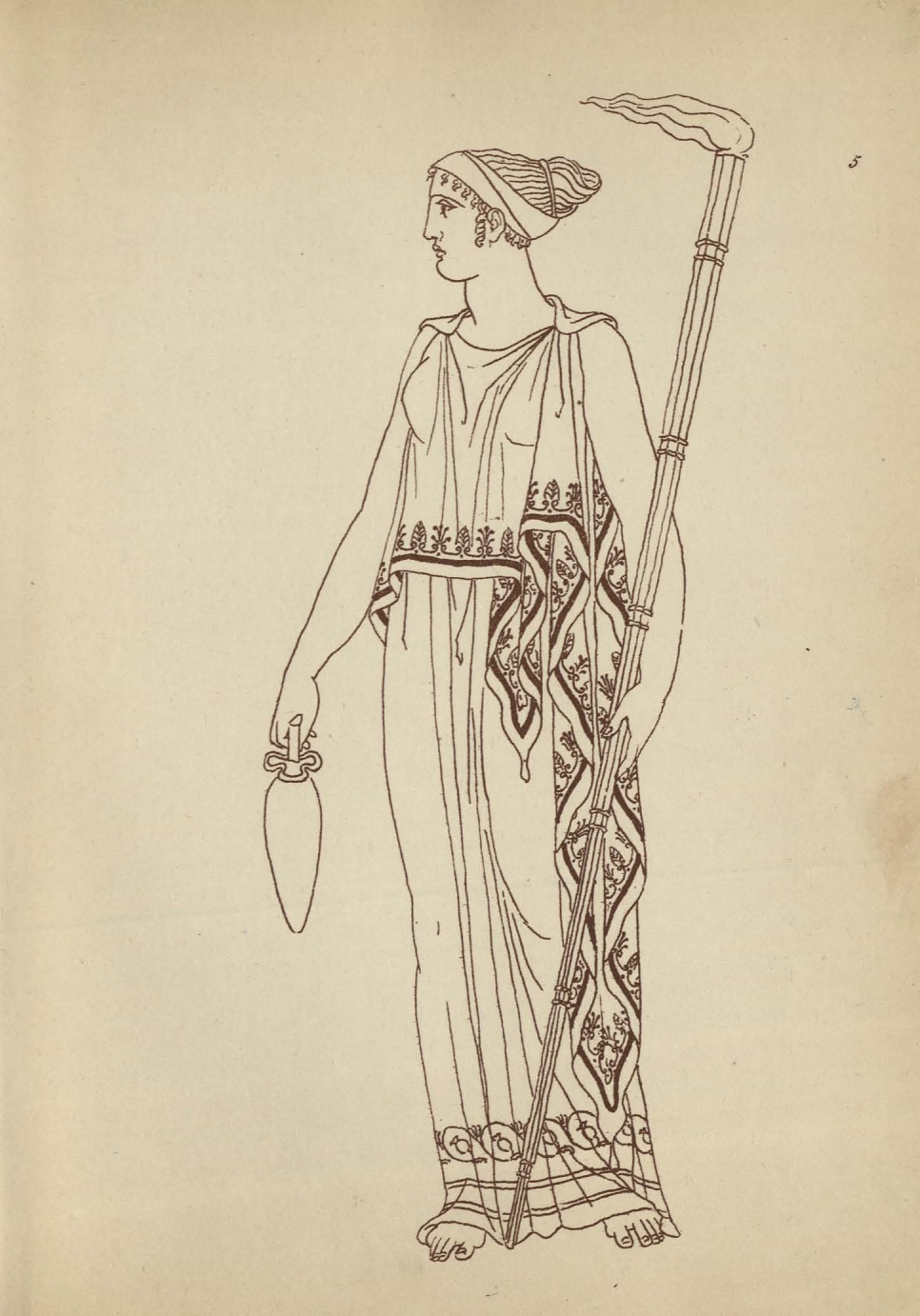

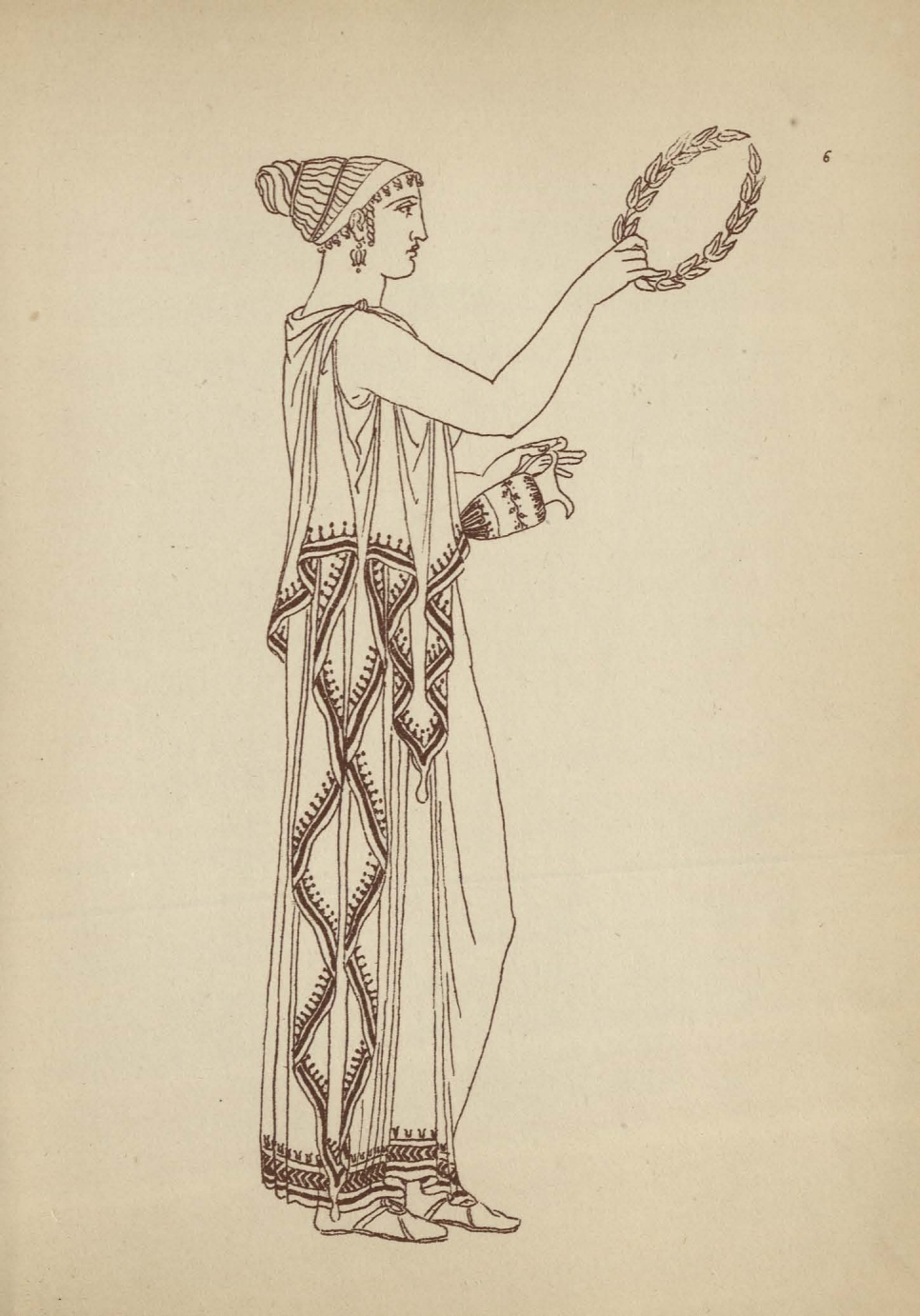

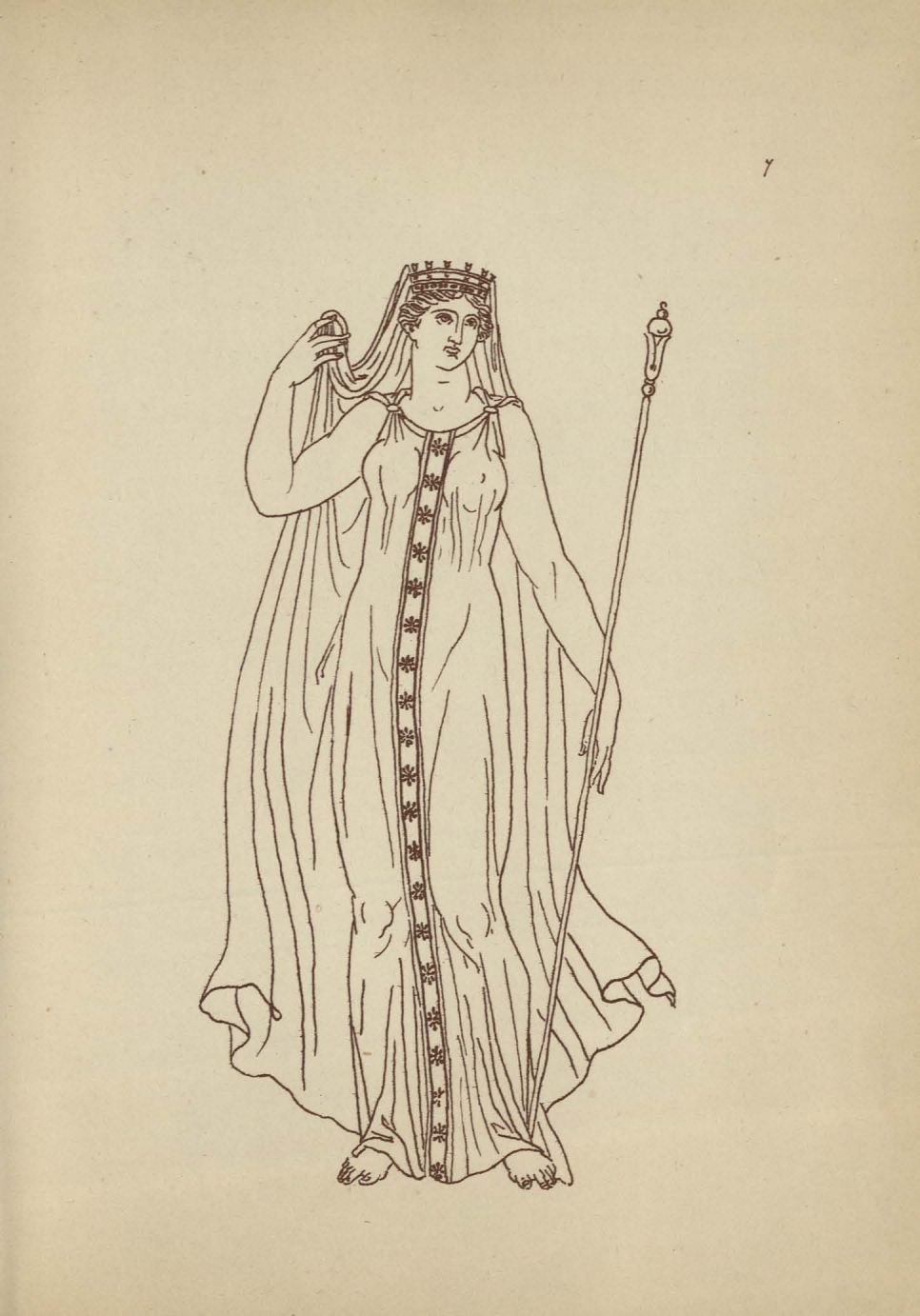

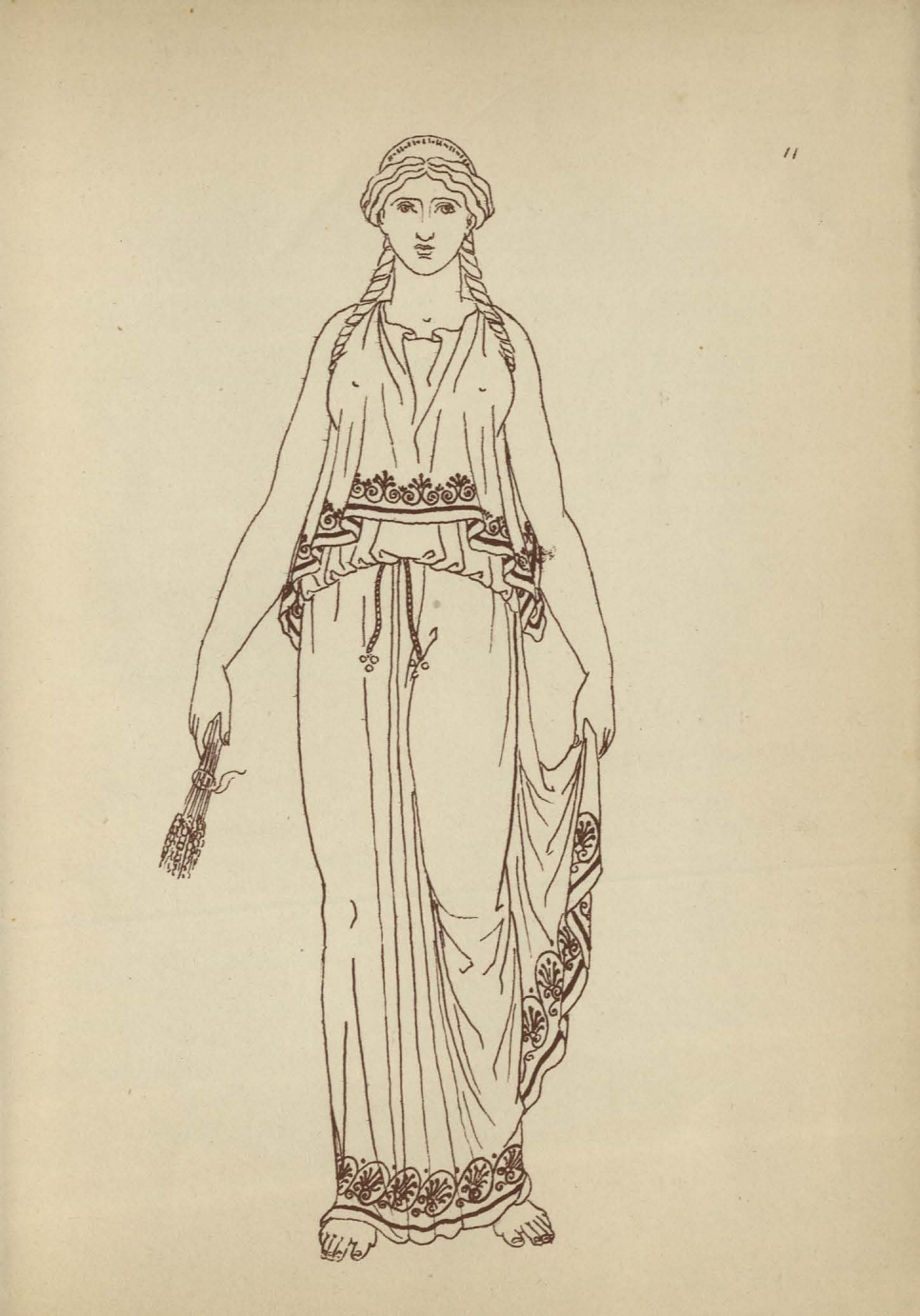

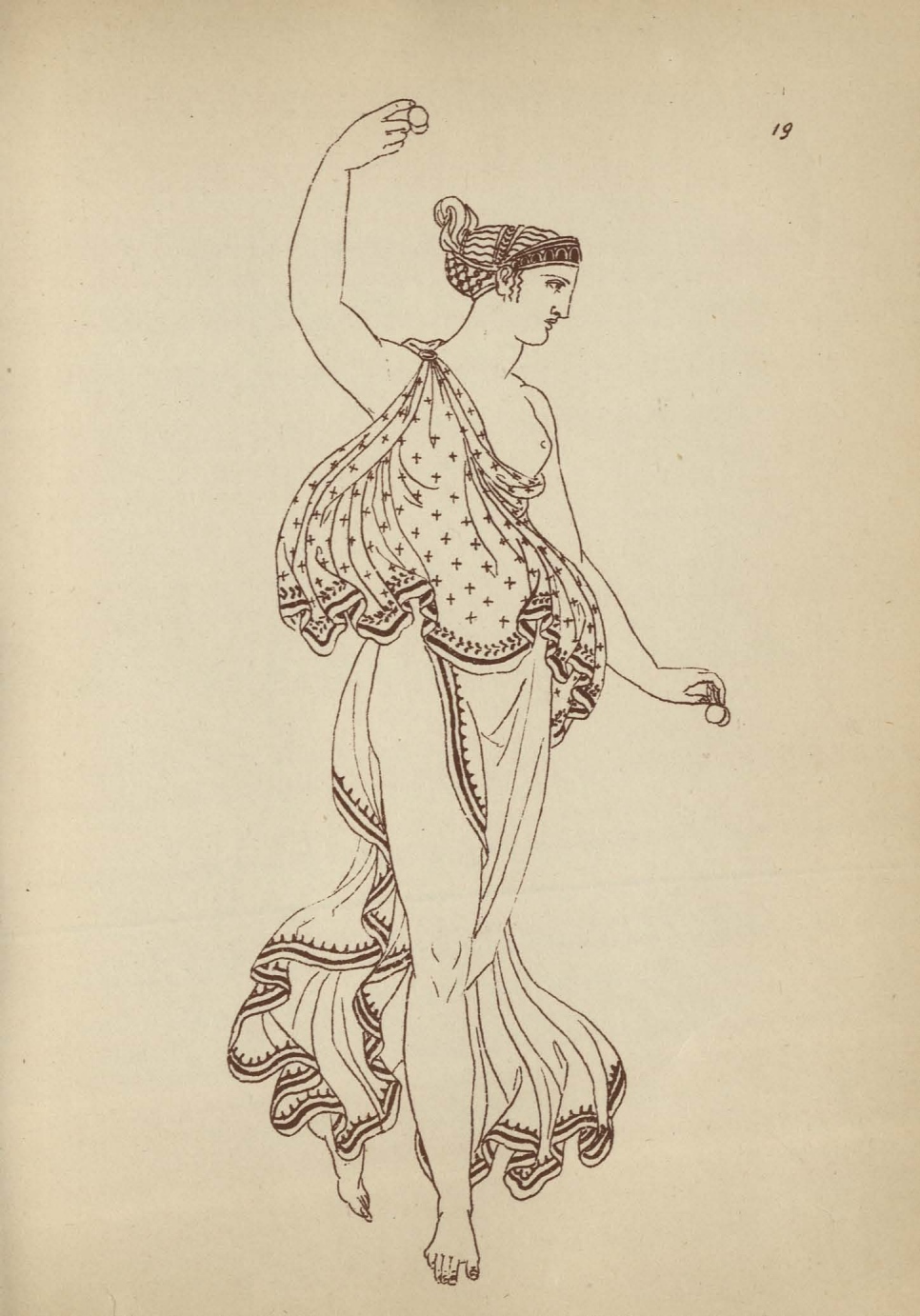

Smith J. M. Ancient greek female costume. — London, 1882Ancient greek female costume : Illustrated by one hundred and twelve plates and numerous smaller illustrations : With explanatory letterpress, and descriptive passages from the works of Homer, Hesiod, Herodotus, Æschylus, Euripides, Aristophanes, Theocritus, Xenophon, Lucian, and other greek authors, / selected by J. Moyr Smith. — London : Sampson Low, Marston, Searle & Rivington, 1882. — 87 p., 112 p. ill. : ill.PREFACE.

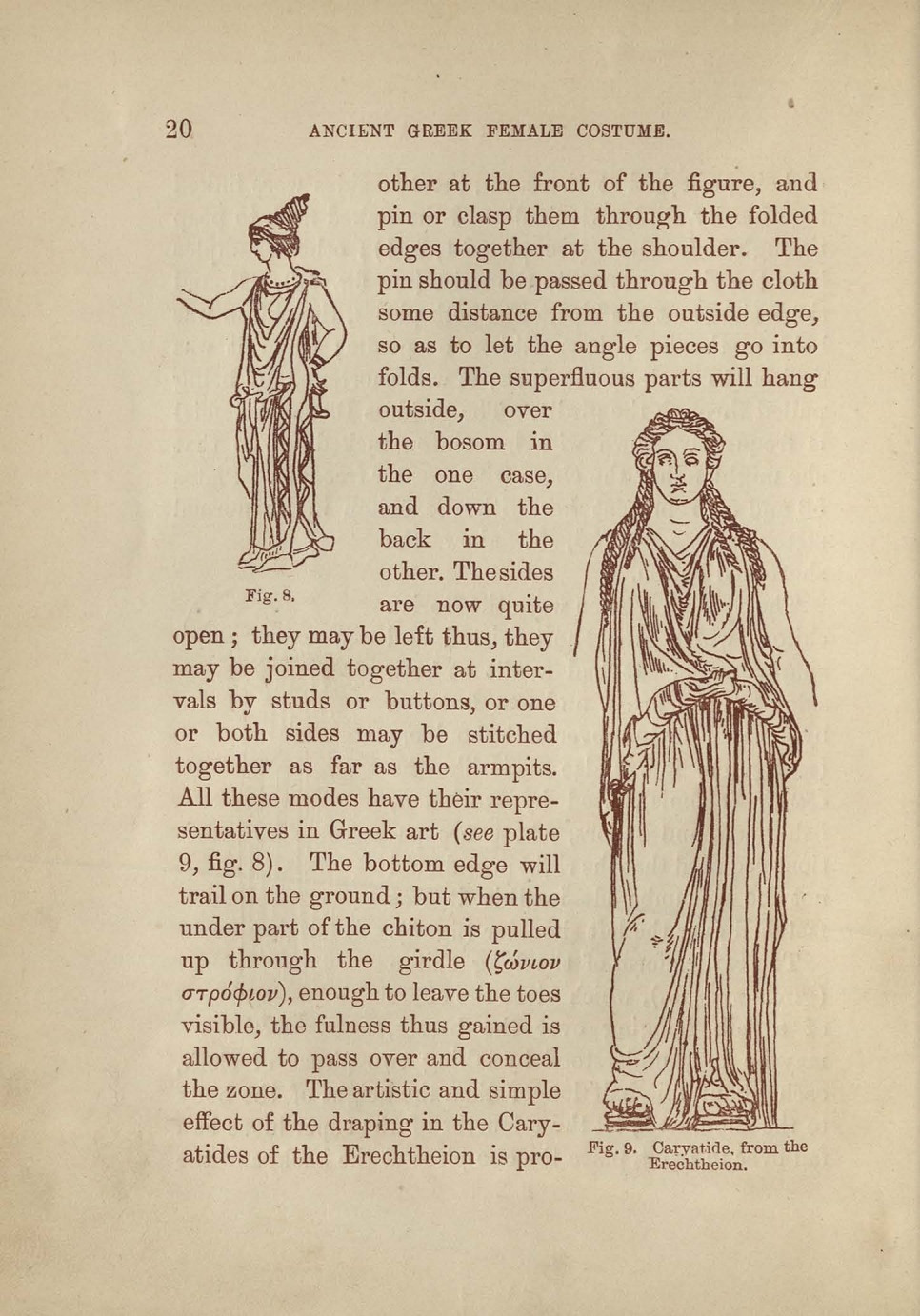

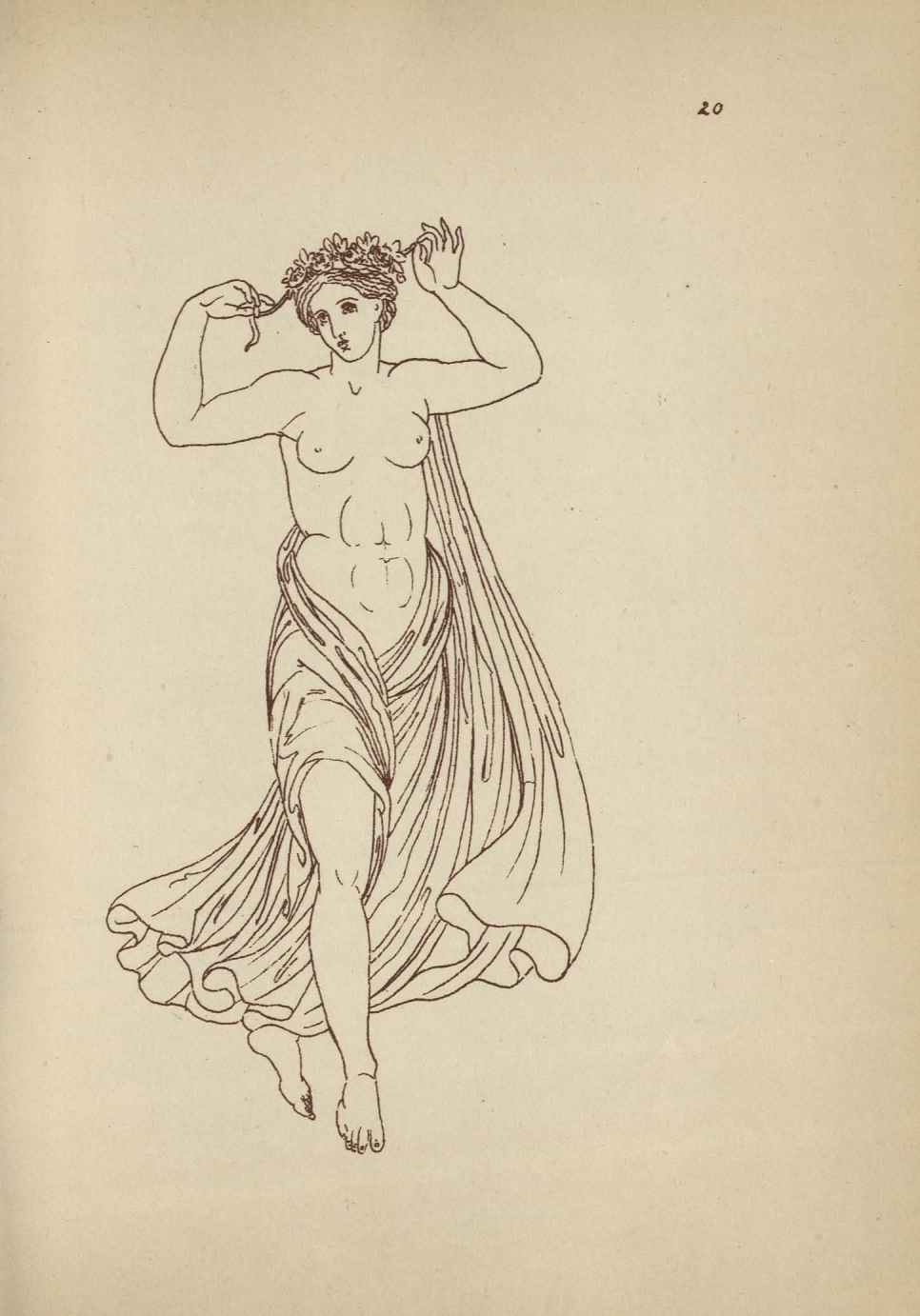

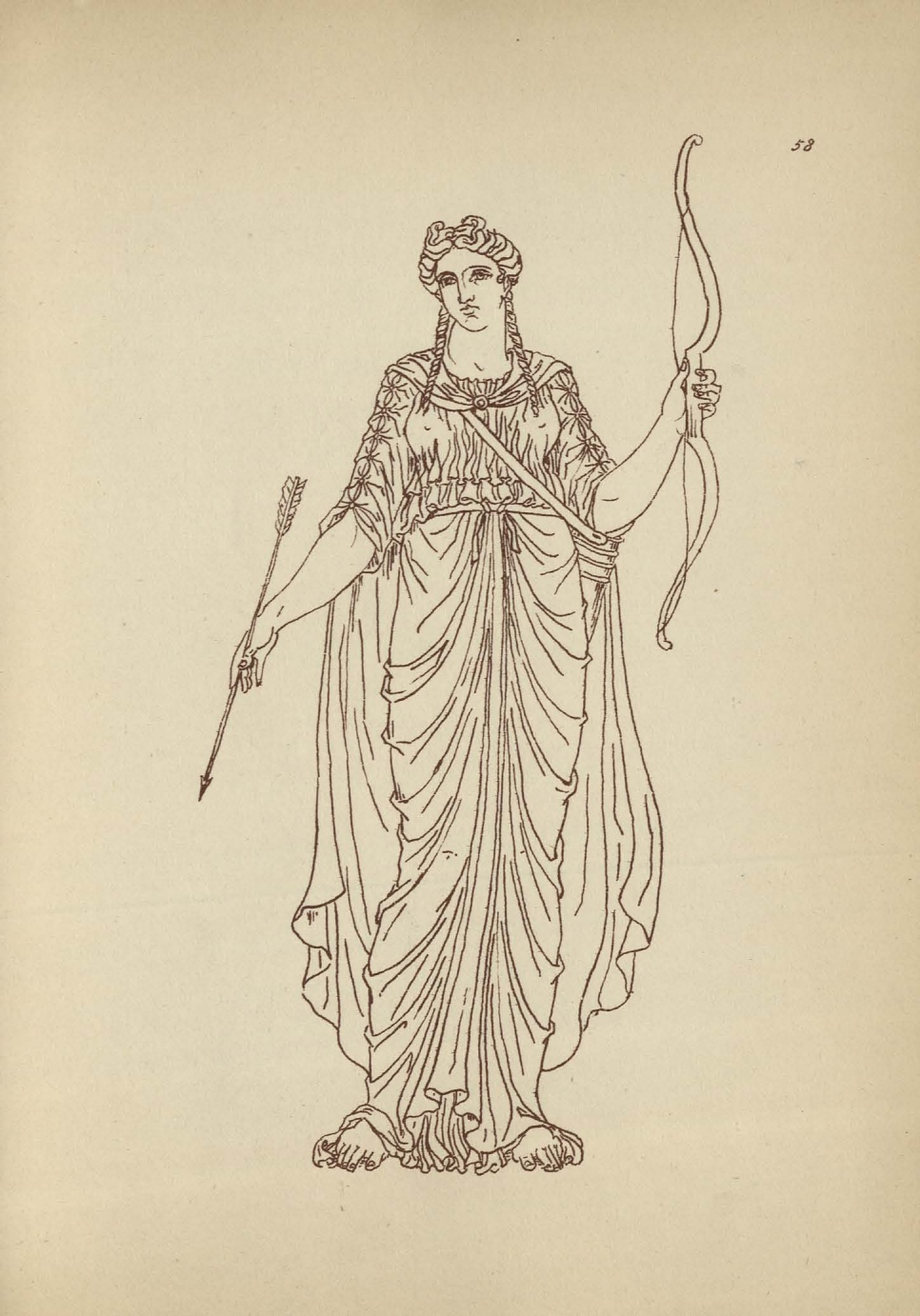

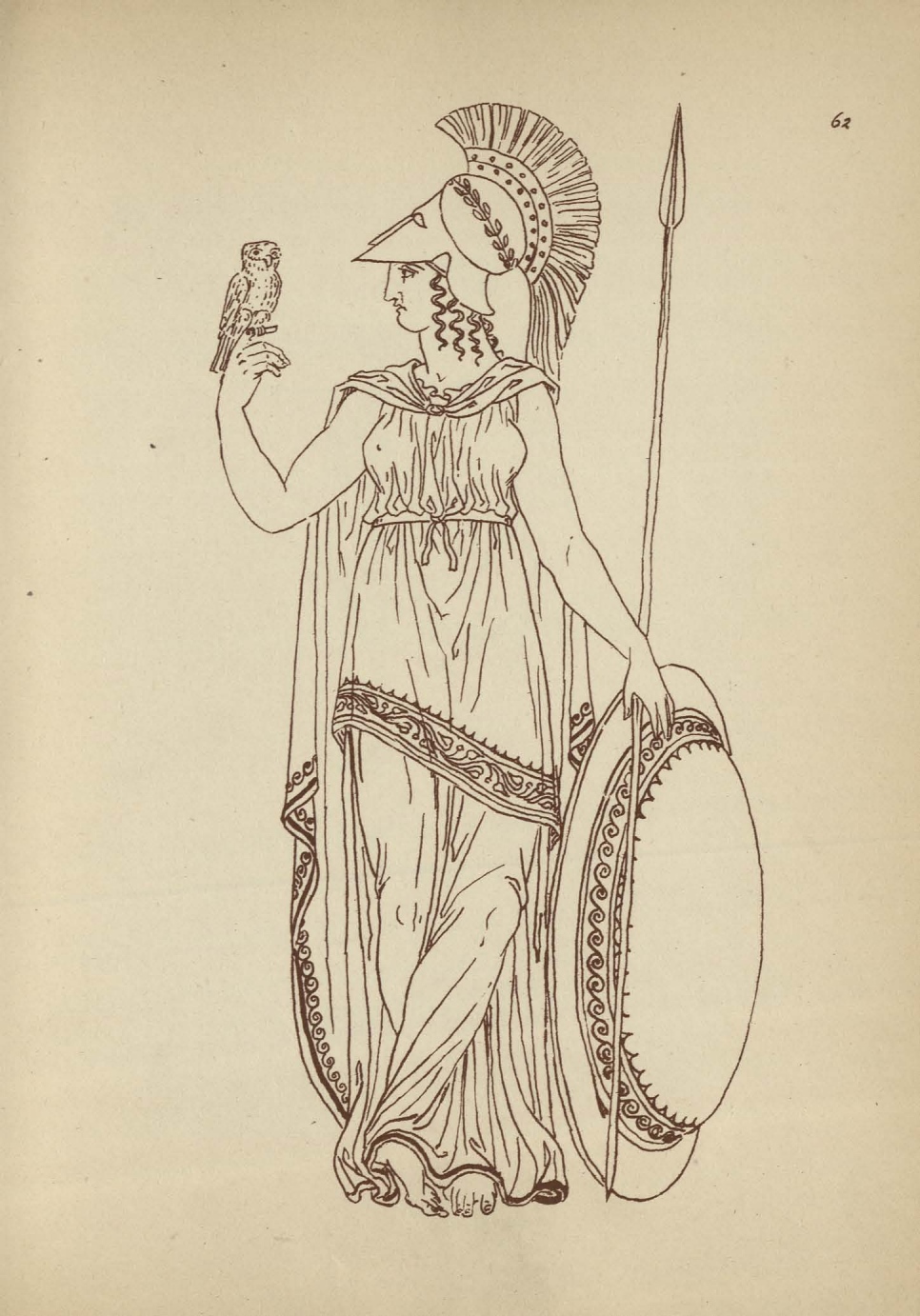

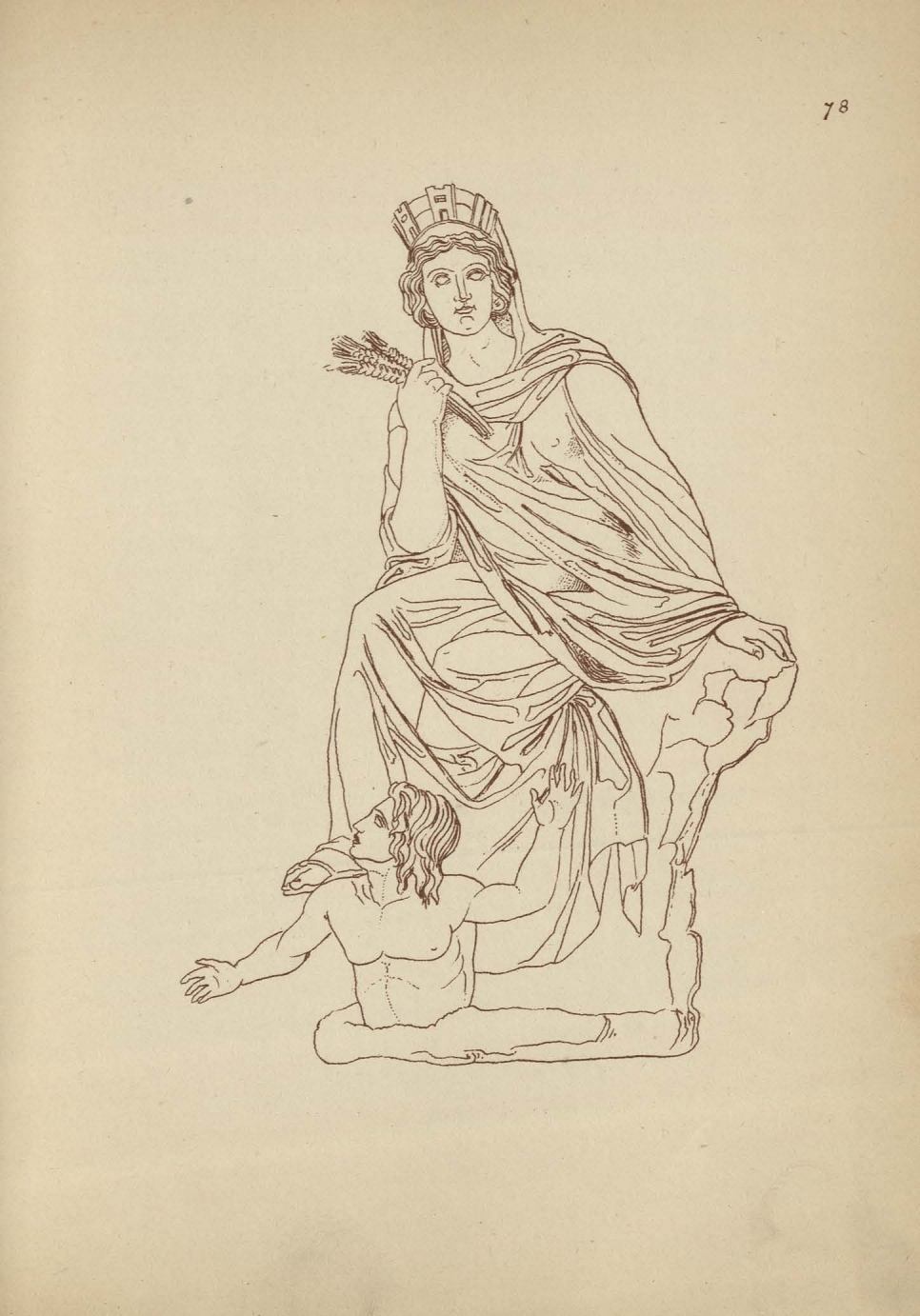

A good many people of fair culture, if asked their opinion of Greek costume, would say that correct Greek costume seemed to consist chiefly of a pair of sandals for the feet, and a ribbon for the hair. In some of the most popular and best known works of Greek art there is even less dress than this. The Venus de Medici has not even a pair of sandals. The statues called the Theseus, the Discobulus, the Laocoon are as bare of clothing, and though the Apollo Belvidere is furnished with a cloak, he does not use it to enshroud his limbs. The popular belief that ancient Greek costume was scarcely appreciable in quantity has thus some apparent foundation in fact. When the question is pressed still further, however, we begin to remember that the Caryatides of the Erechtheion, and the goddess Athénè, have each a distinctive dress covering the whole body, and that several of the female deities, such as Hérè, Cybelè, and Artemis, are scarcely, if ever, represented unclothed.

This limited wardrobe is, however, nearly all that was credited to the Greeks by many people who were far from being ignorant of Greek art and Greek literature.

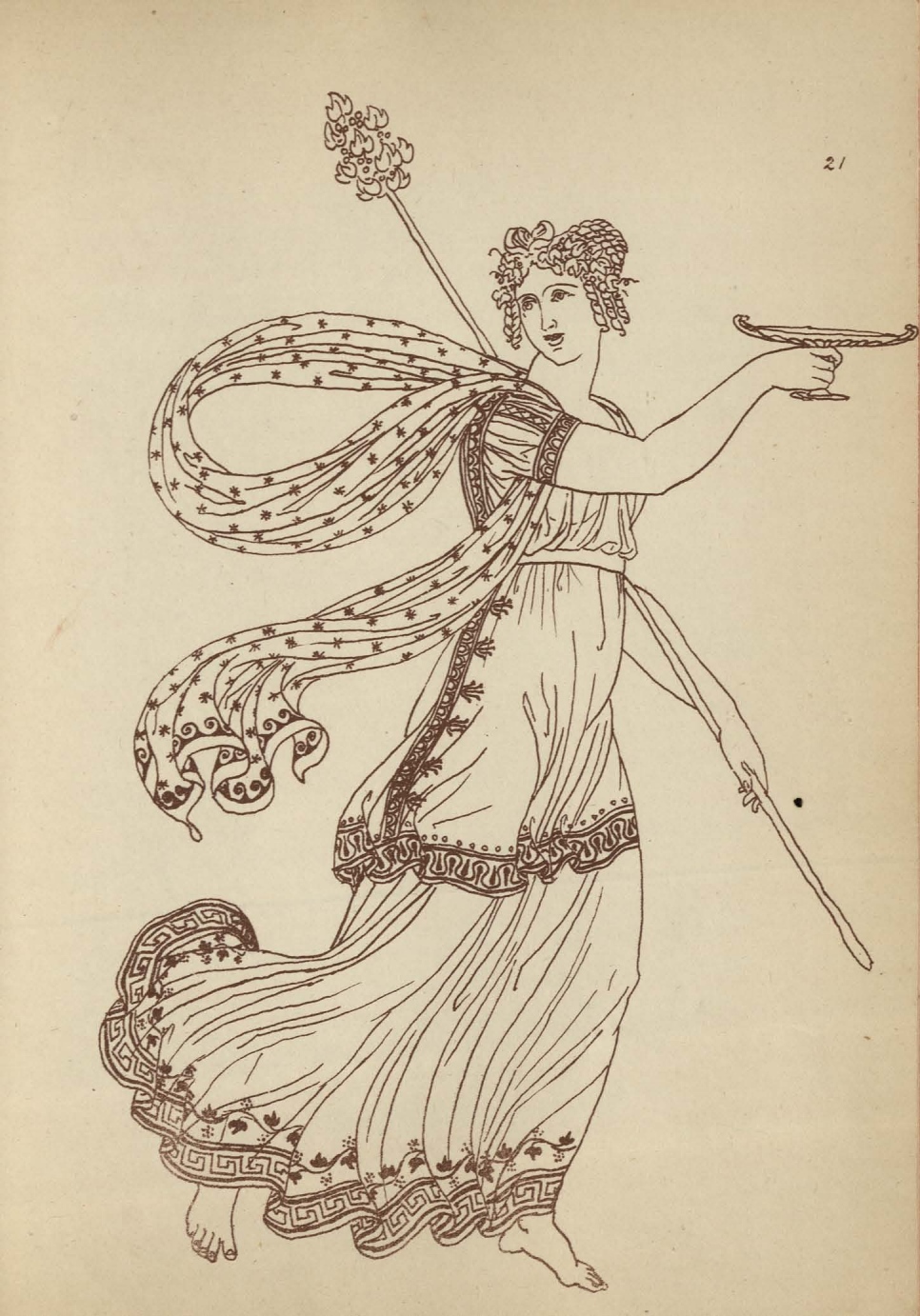

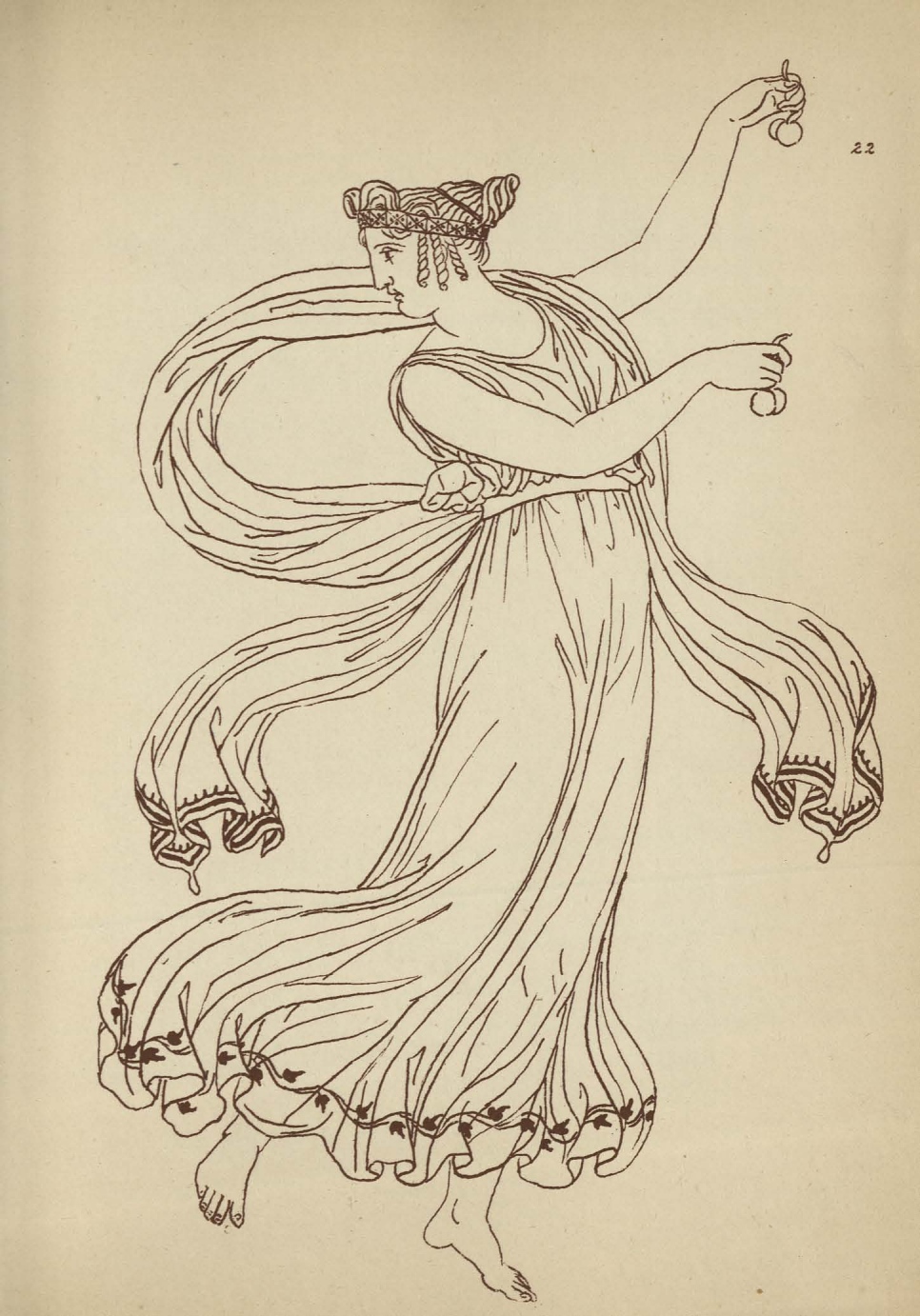

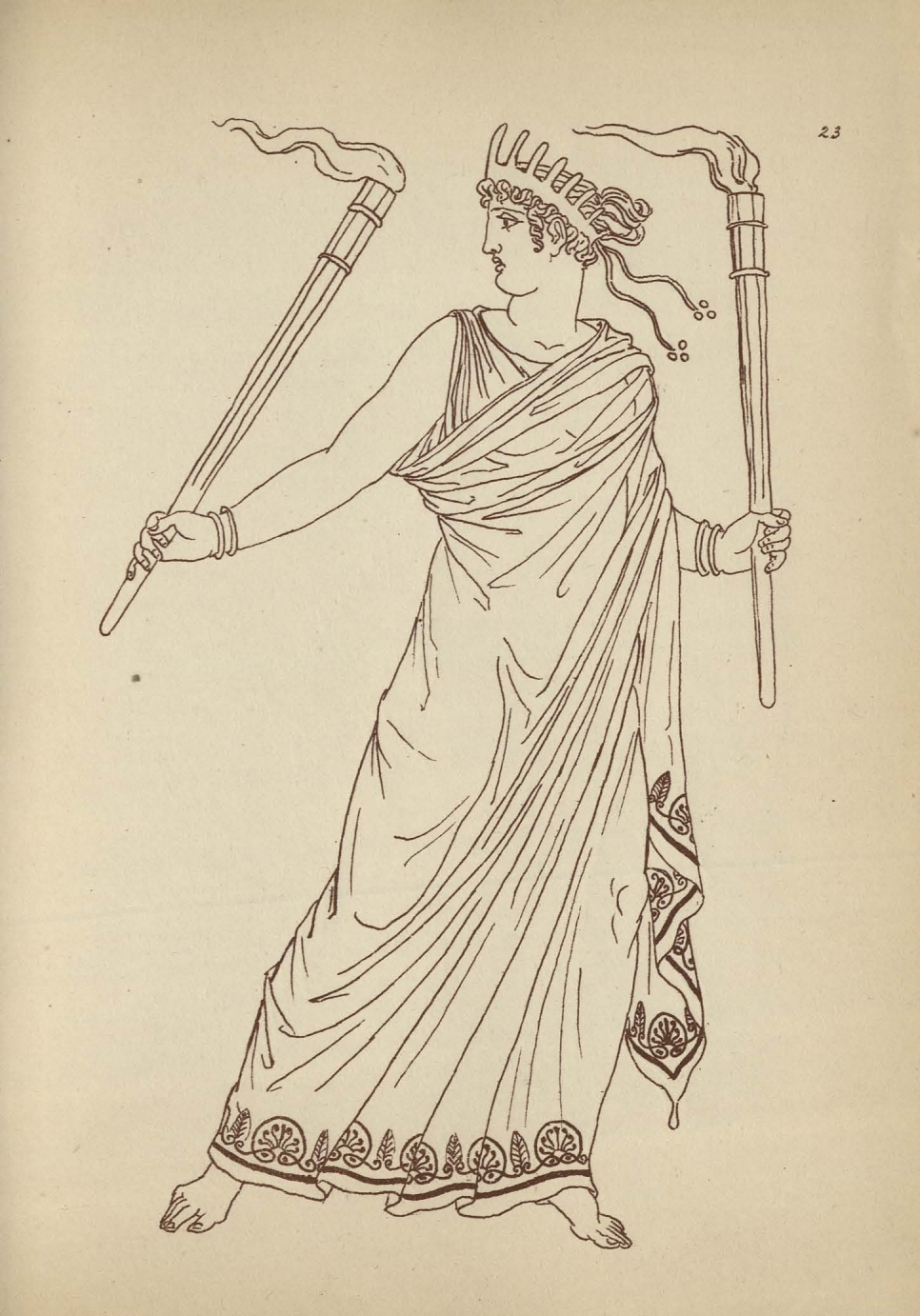

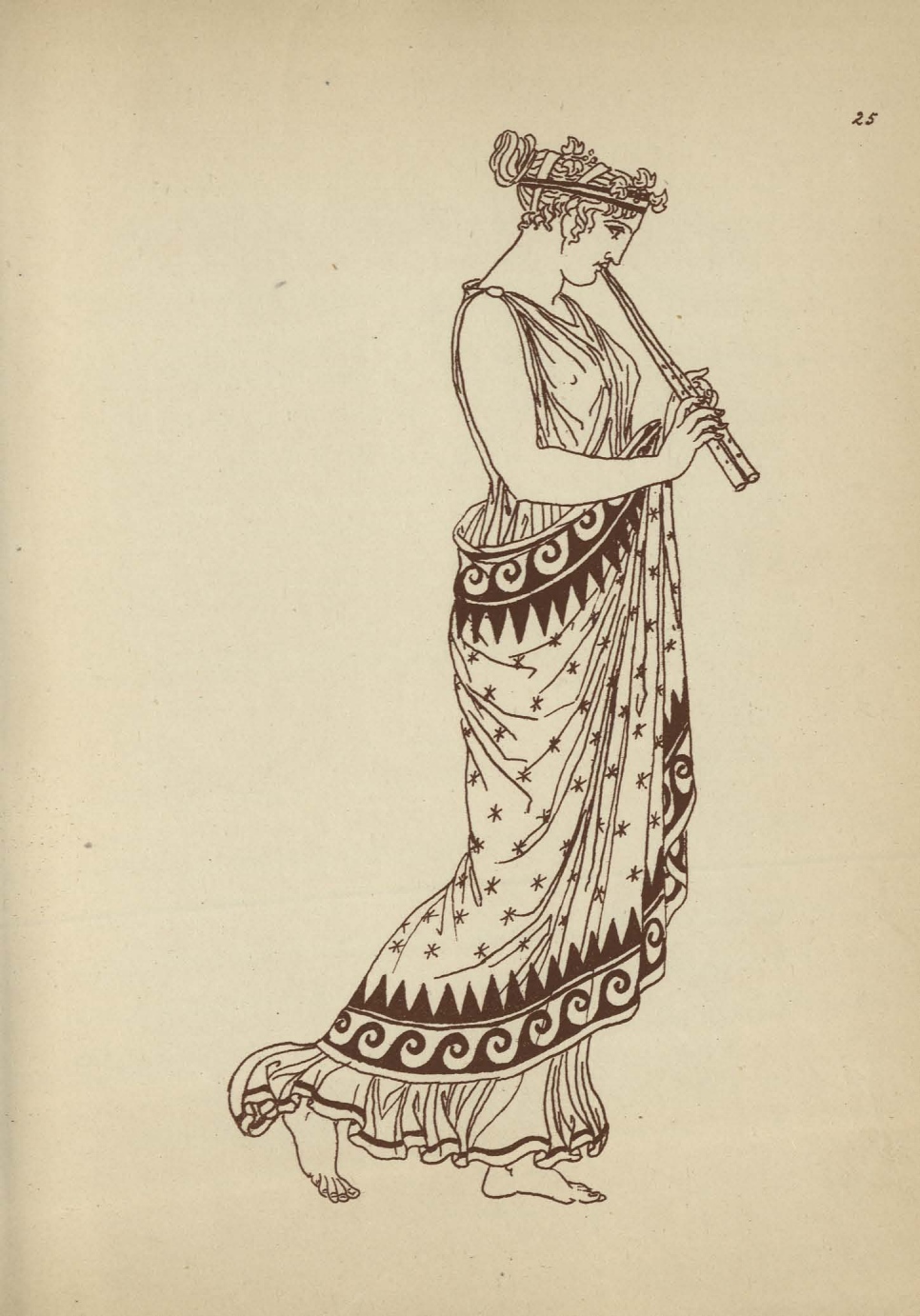

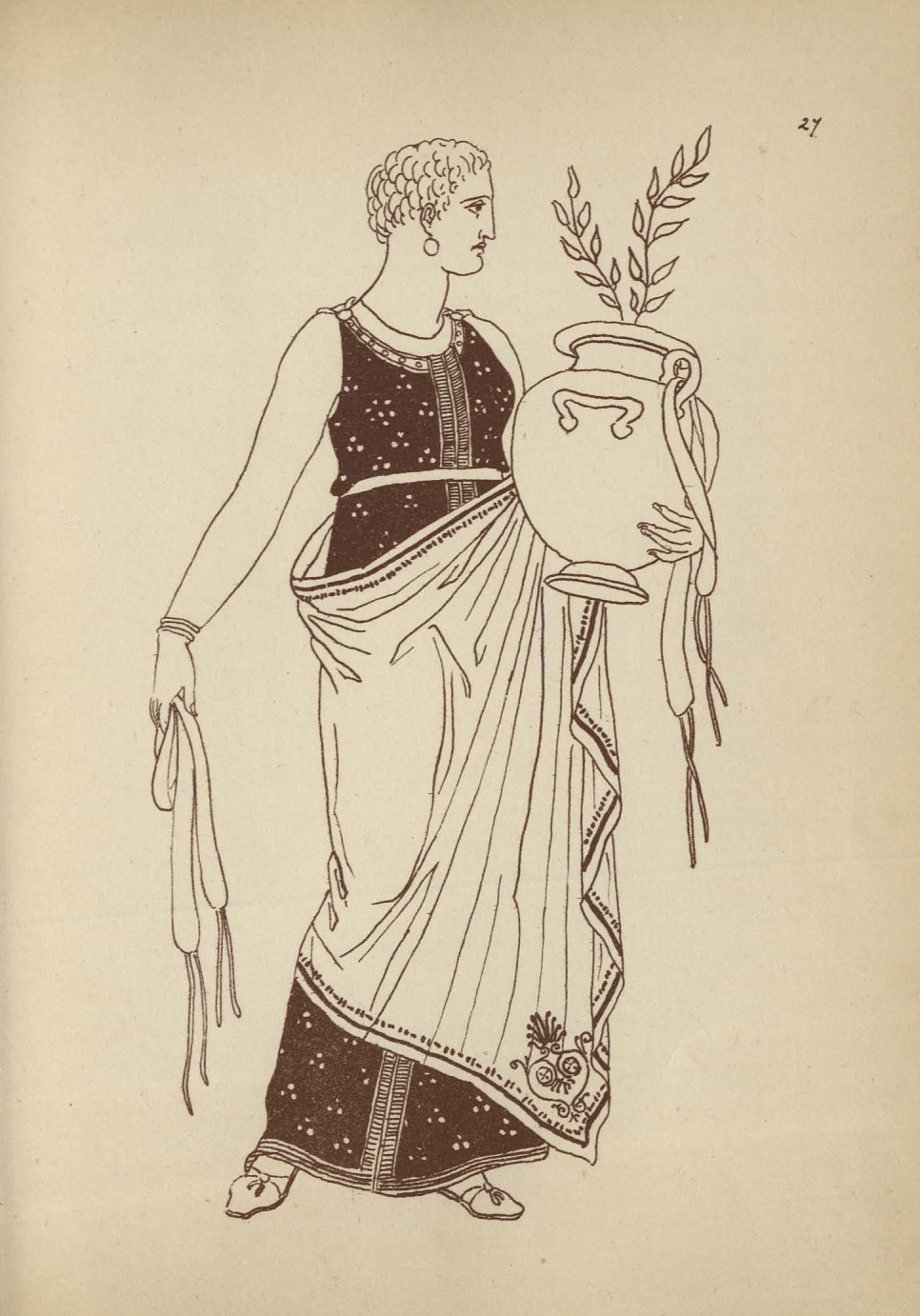

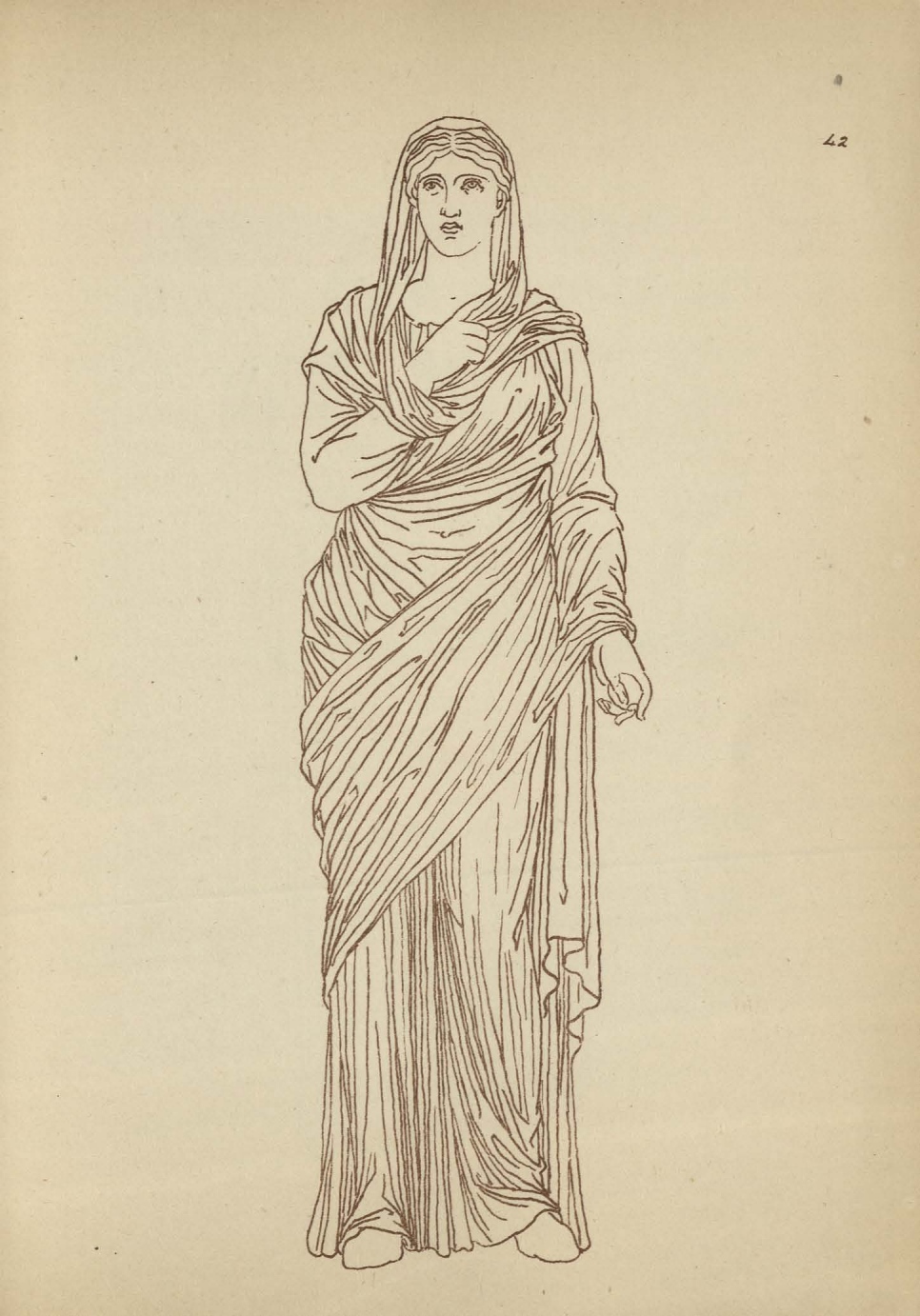

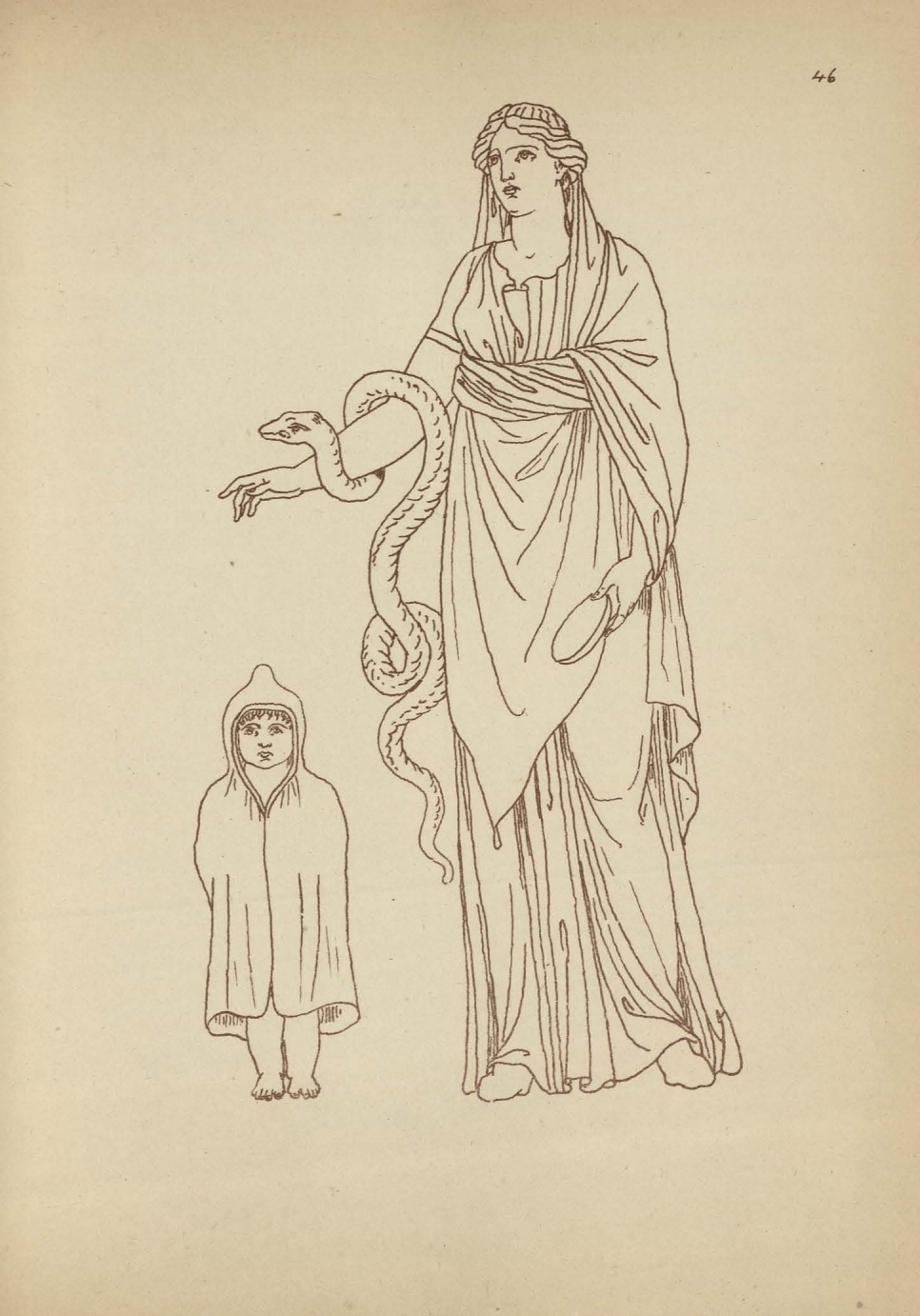

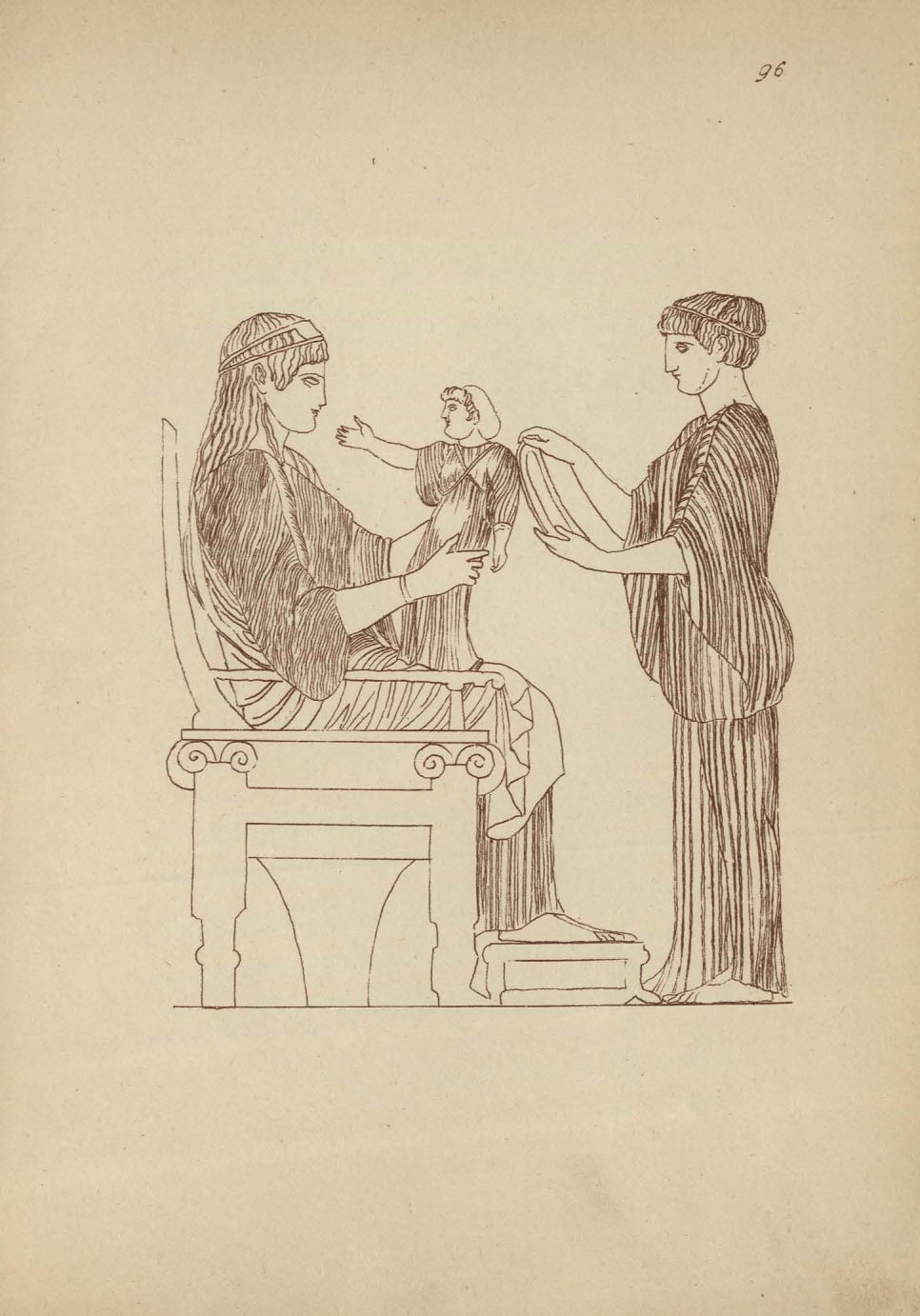

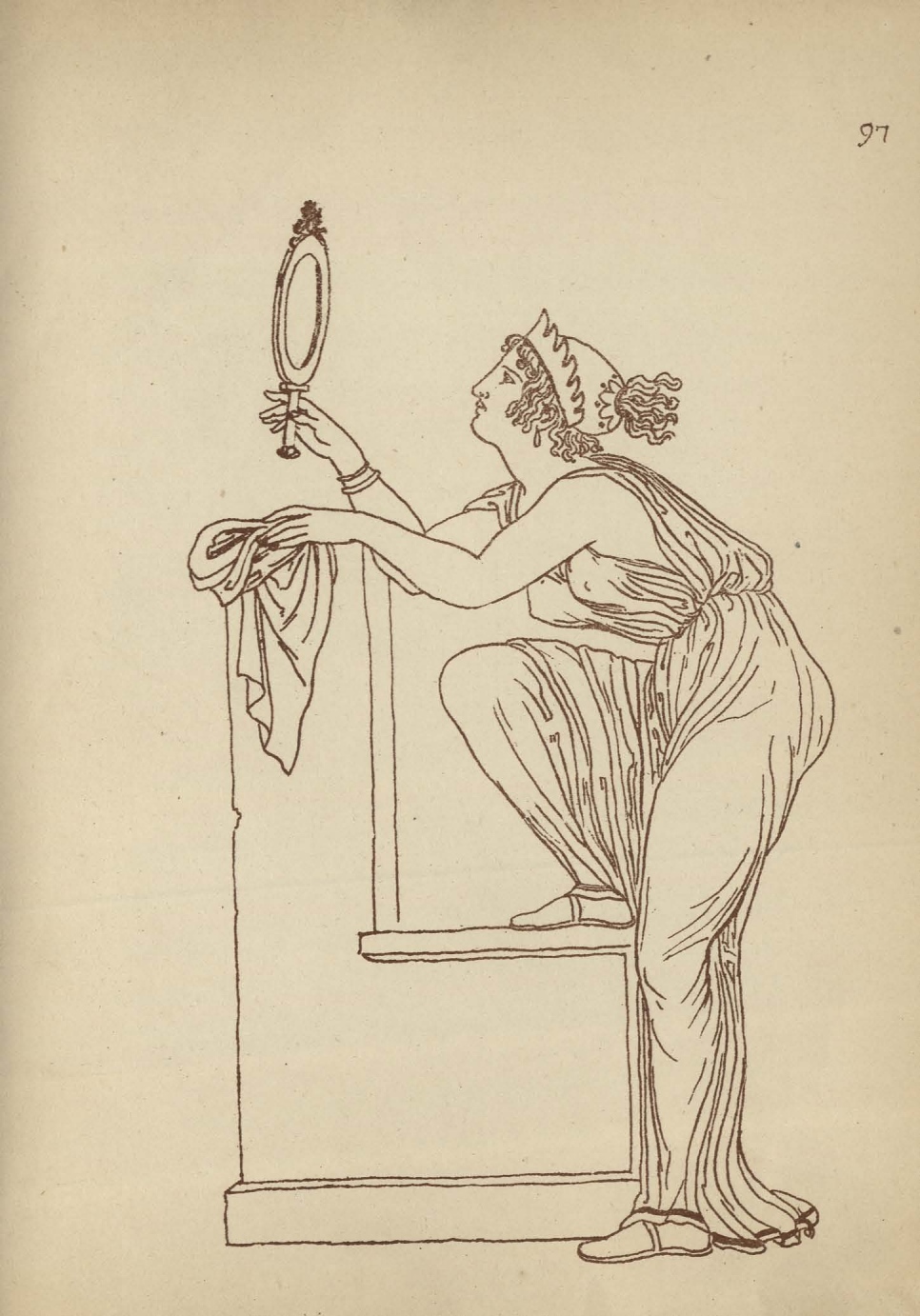

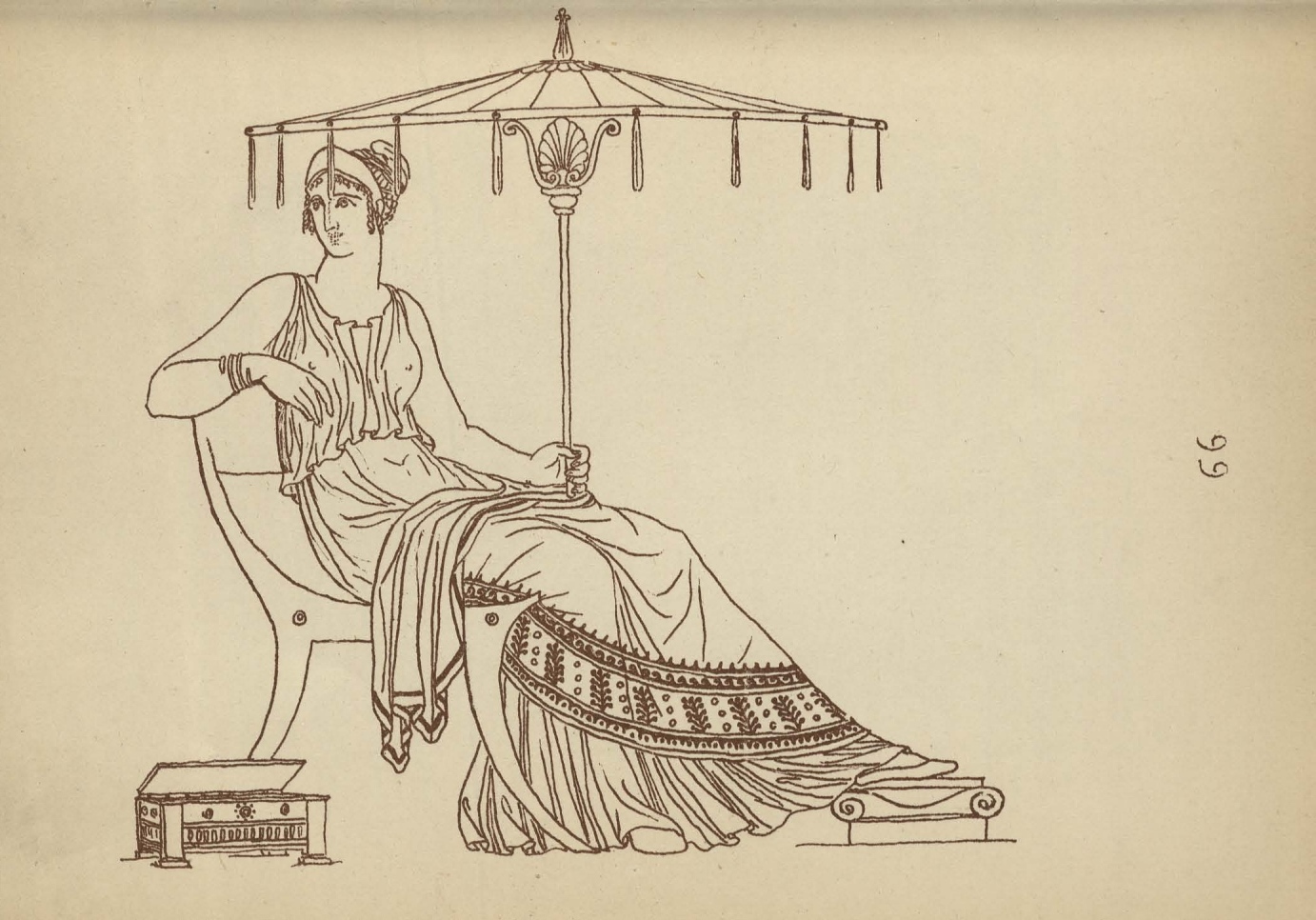

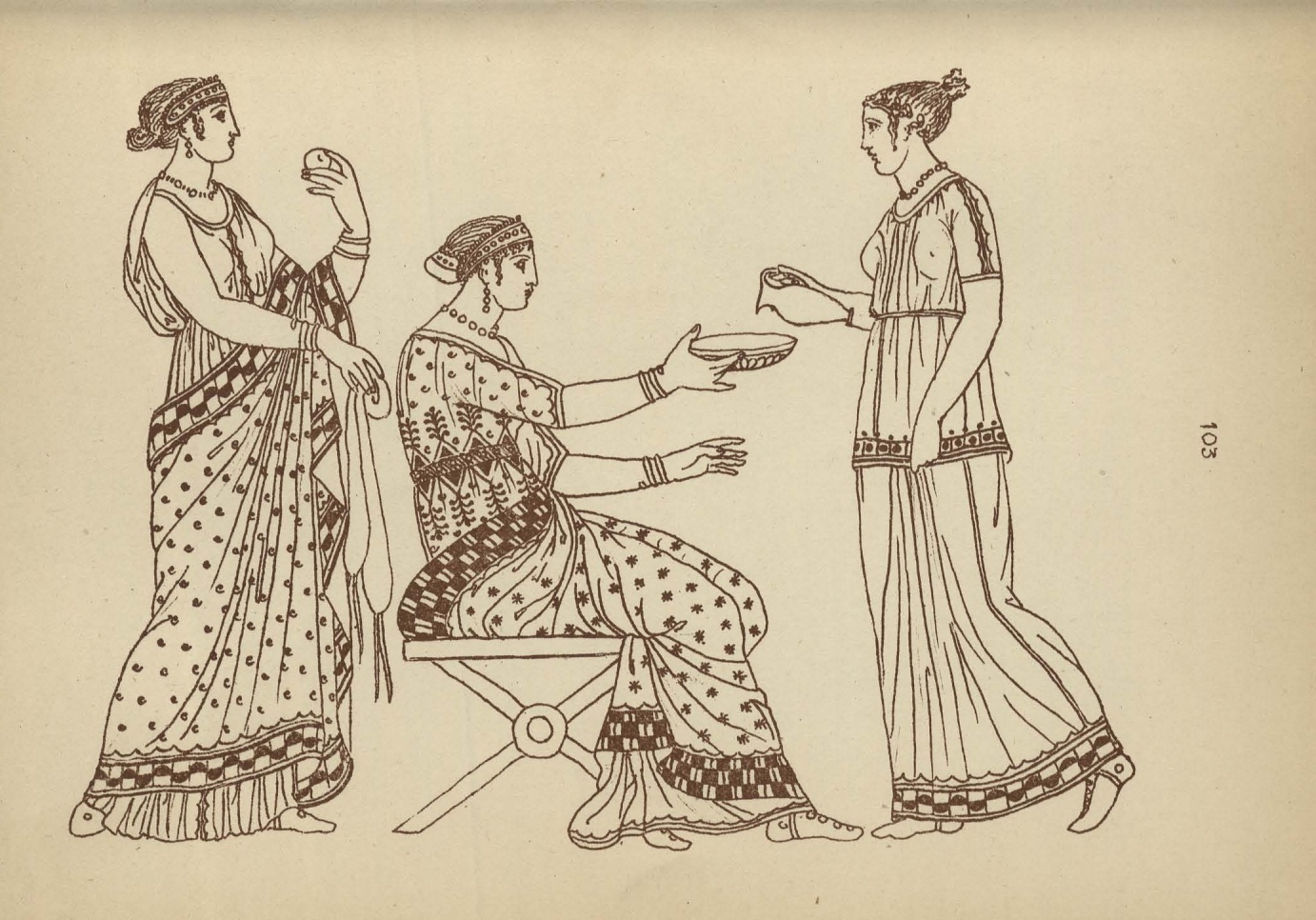

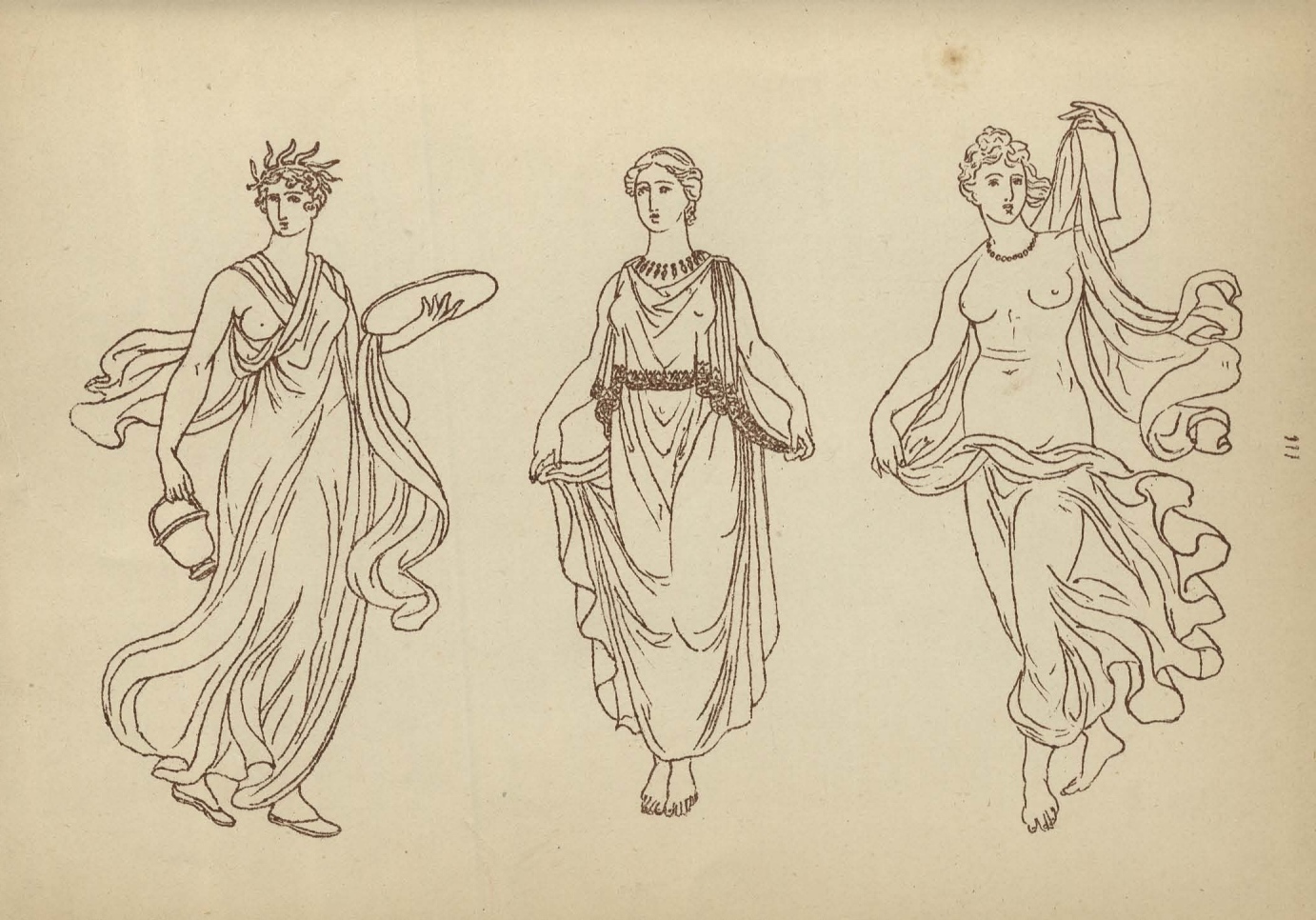

When, however, we come to study Greek literature and Greek art with a view to costume, we are amazed at the richness and diversity for which Greek dresses were distinguished. In literature, Homer is full of allusions to magnificent dresses; and the paintings on vases supply us with hundreds of realistic representations of costumes which were undoubtedly taken from models in daily life.

To account for this seeming discrepancy we must call to mind that the most popular Greek statues nearly all belong to one period of Hellenic art, and that these statues were the product of a time when sculptural art had reached its zenith. As the human form unclothed gave the sculptor a fairer opportunity of showing his transcendent abilities — the mastery of form and the rendering of flesh being more difficult than the sculpture of drapery — he naturally chose subjects on which the dress was scanty and the limbs well displayed.

Representations of nude figures do occur in archaic sculpture and pottery, but they are chiefly bacchanalian subjects; and, as a rule, the figures in early examples are all dressed. Aphroditè (Venus) is clothed, and Heraclês is everywhere seen wearing the spoils of the Nemean lion. But no sculptural models of these were made, they were seldom photographed, and rarely seen; when seen they were passed over with a smile at their quaint inartistic stiffness, and scarcely admitted by the purists to be Greek art at all. Hence, in spite of the teeming examples of varied costumes exhibited on the Greek vases, and in early statues and bas-reliefs, ordinary culture persisted in recognizing as Greek only the works of the age of Phidias, or works which followed the usages of the Phidian period of sculpture.

Though I have been interested in Greek costume for many years, it was only comparatively recently that I discovered that such a book as Hope’s “ Costumes of the Ancients ” existed. It was a revelation of tbe diversity, beauty, fitness, and grace of the early Greek dress, and also showed that culture, research, and enterprise at the beginning of this century were well directed.

It is from this book, published in 1812, and from Muller’s “Denkmäler,” that the plates and some of the cuts in the letterpress have been taken. To render the work more complete, various other illustrations have been added; these have been drawn direct from the paintings on ancient vases in the British Museum and the Louvre.

In the arrangement of the plates I have not been guided entirely by chronological sequence, but have rather endeavoured to group figures with similar kinds of dresses together; so that the artist or decorative draughtsman who wishes to make use of the book may find various dresses of the same kind with the least possible trouble.

In the letterpress I have generally retained the usual Latinized form of spelling Greek proper names, though I am aware there is at present a taste for the original Greek form. But in a work that appeals not to scholars but to lovers of art, it would probably only lead to confusion were the reader to find the familiar Circe, Cyclades, Sicily, and Thrace under the forms of Kirkê, Kuklades, Sikania or Sikelia, and Thrakia. Moreover, those who have attempted to reform our spelling in this respect have usually carried out their improvements in a very imperfect way. In some instances that I have seen, one half of a name has the Greek form, and the other half is in the familiar Latinized form. Nor do I think that those people who spell Pheidias for Phidias and Phoibos for Phœbus will do Greek any great service by this display of scholarship while the ridiculous English style of pronouncing Greek is retained; the popular pronunciation of Phœbus is much nearer the Greek original than the popular English pronunciation of Phoibos would be. When, however, the Latin name is so altered as to be entirely different from the Greek, I sometimes use the Greek name in preference to the Latin one, as Aphroditè for Venus, Athénè for Minerva, and Odysseus for Ulysses.

Sample pages

Download link (pdf, yandexdisk; 51,0 MB)

18 октября 2017, 11:06

0 комментариев

|

Партнёры

|

Комментарии

Добавить комментарий