|

|

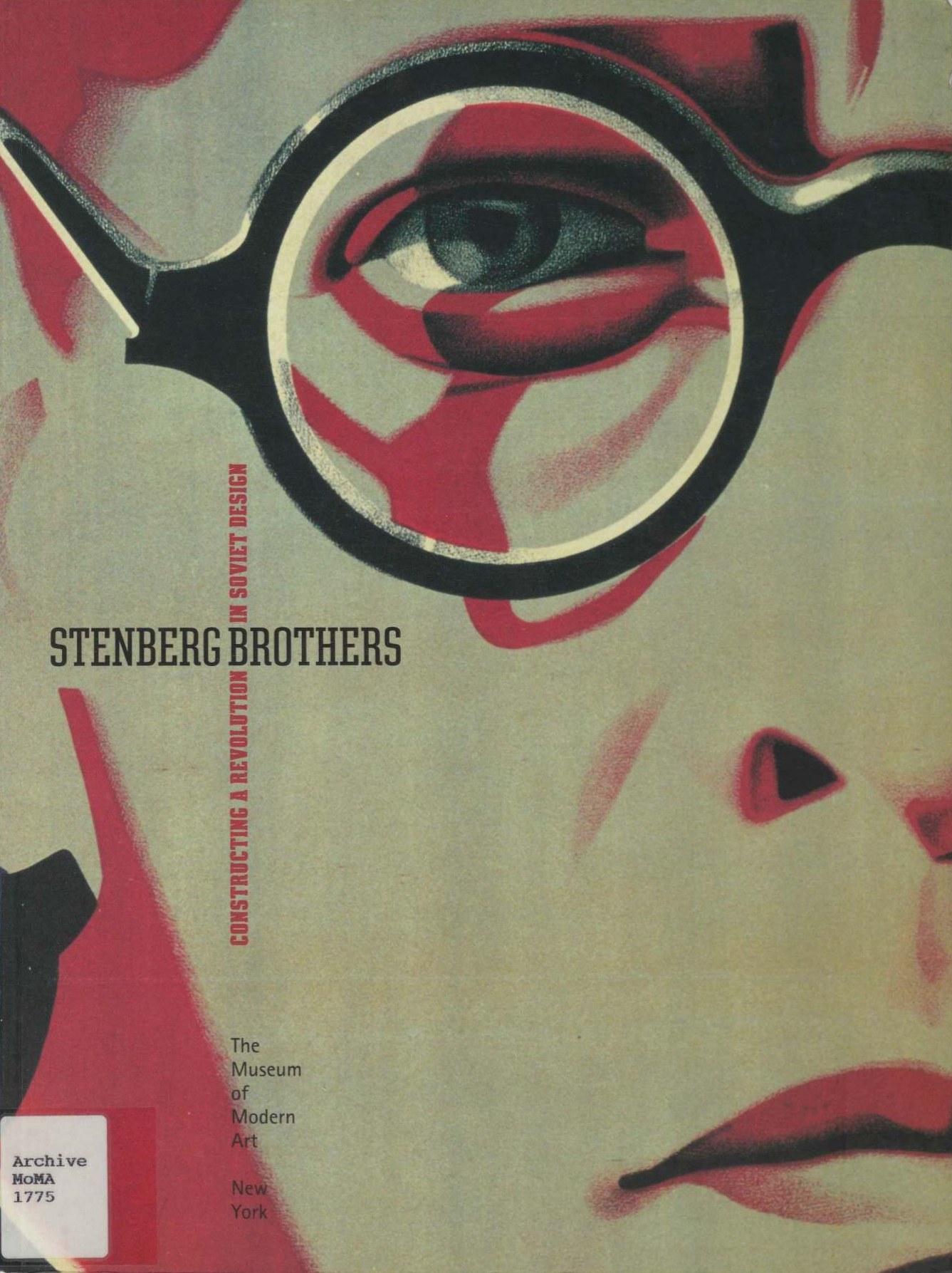

Stenberg Brothers : constructing a revolution in Soviet design. — New York, 1997Stenberg Brothers : constructing a revolution in Soviet design / by Christopher Mount, with an essay by Peter Kenez. — New York : The Museum of Modern Art, 1997. — 96 p., ill. — ISBN 0-87070-051-0, 0-8109-6173-3

Published on the occasion of the exhibition Stenberg Brothers: Constructing a Revolution in Soviet Design, directed by Christopher Mount, Assistant Curator, Department of Architecture and Design, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, June 10 to September 2, 1997.

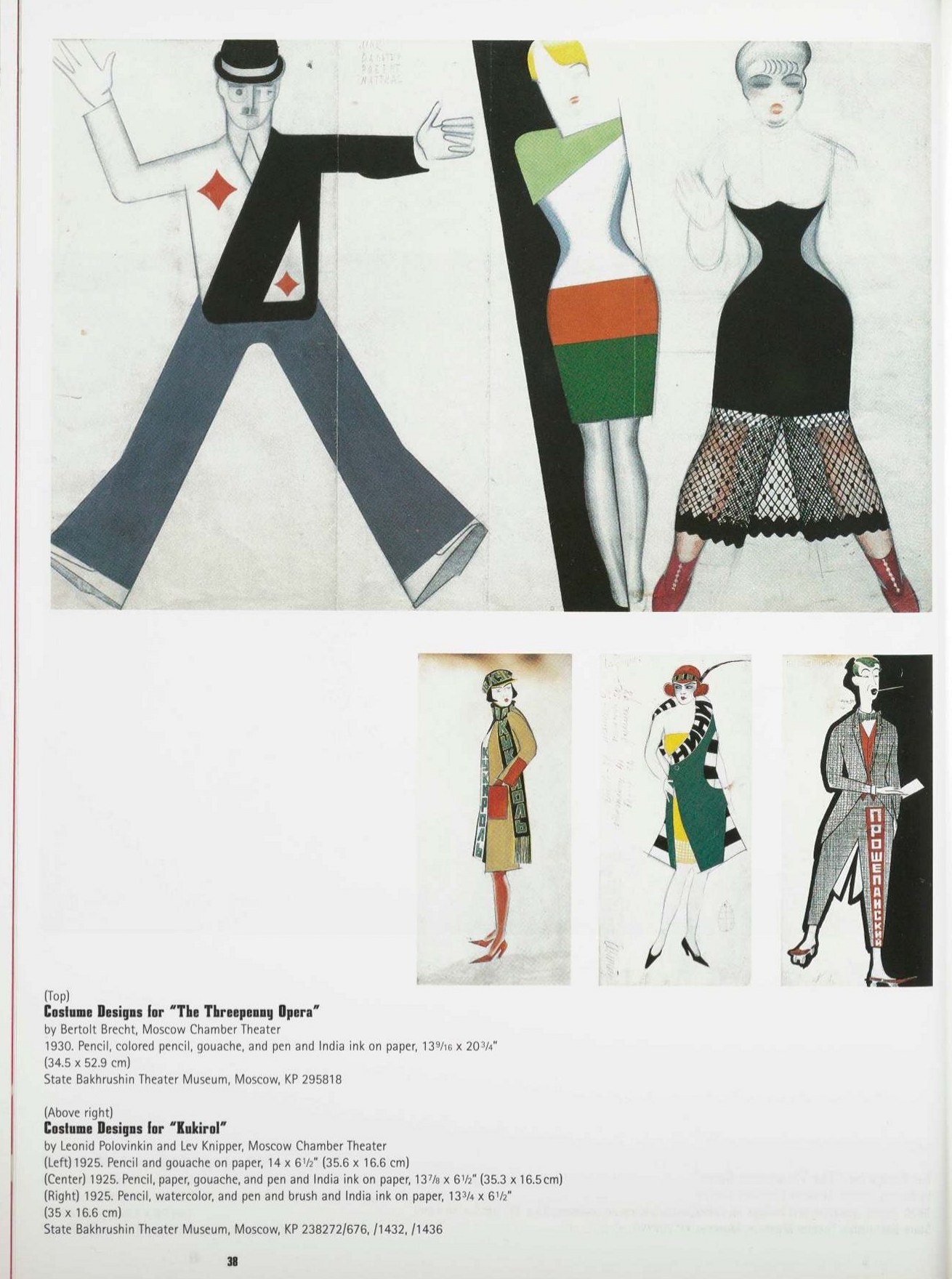

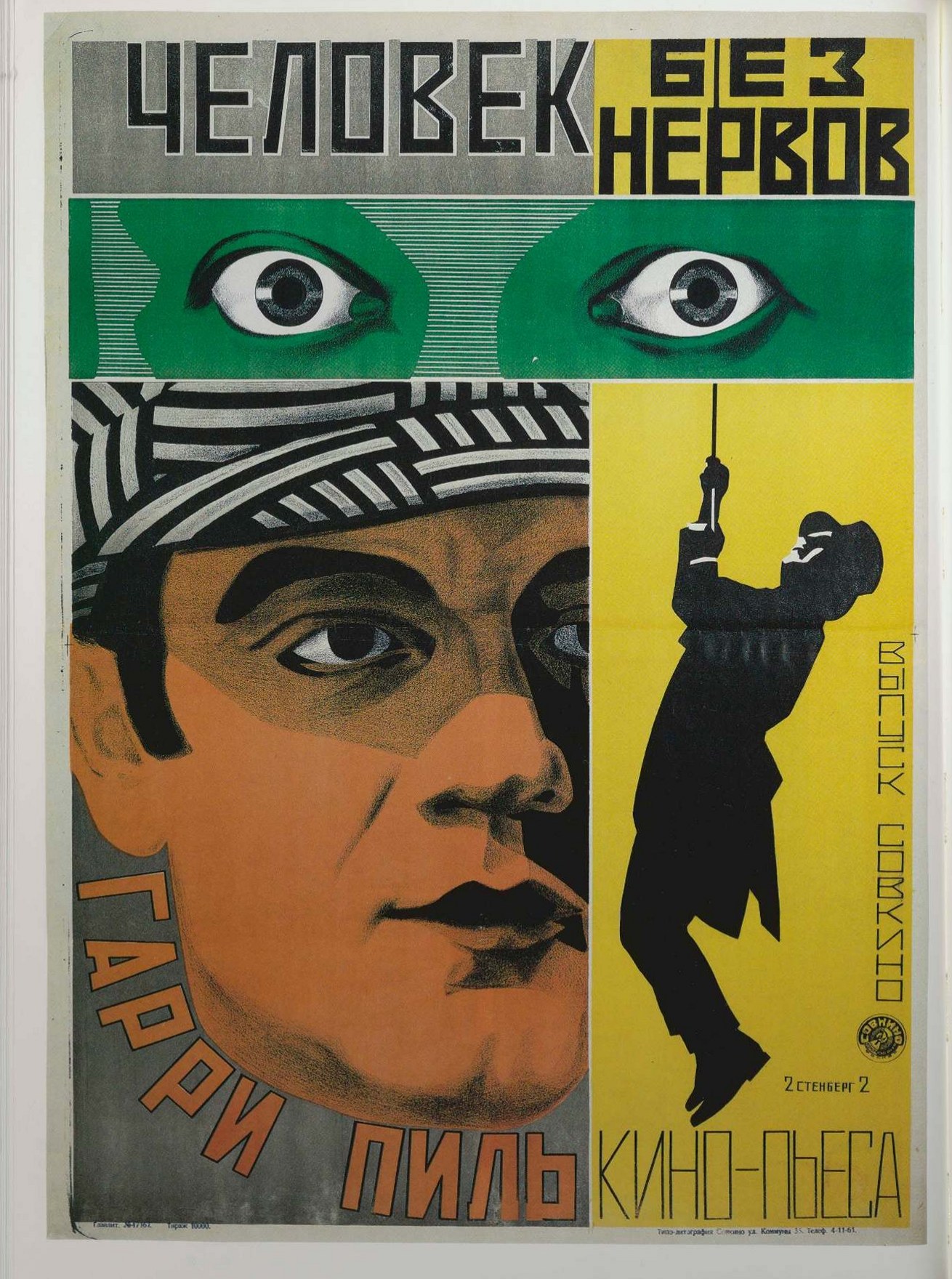

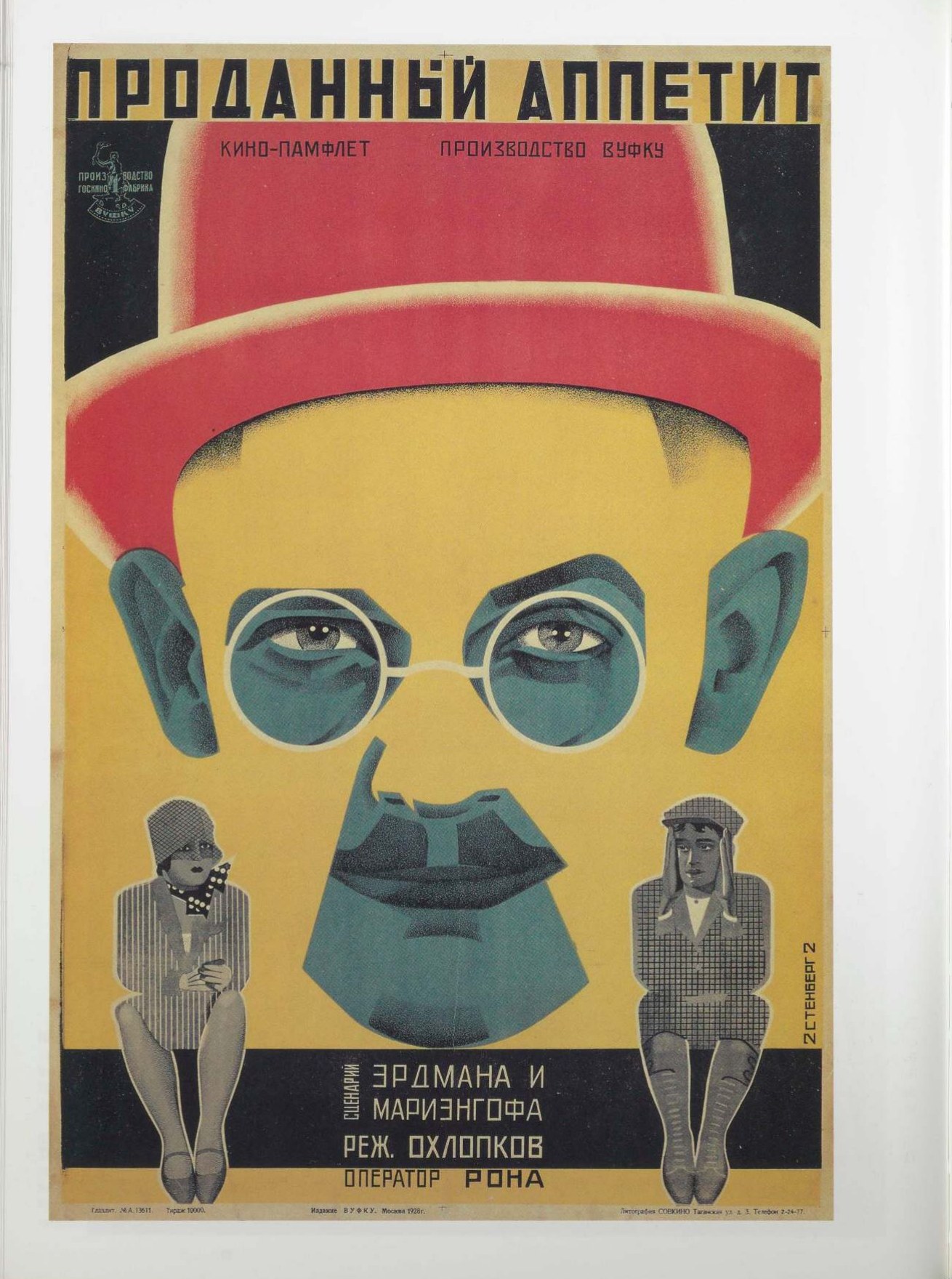

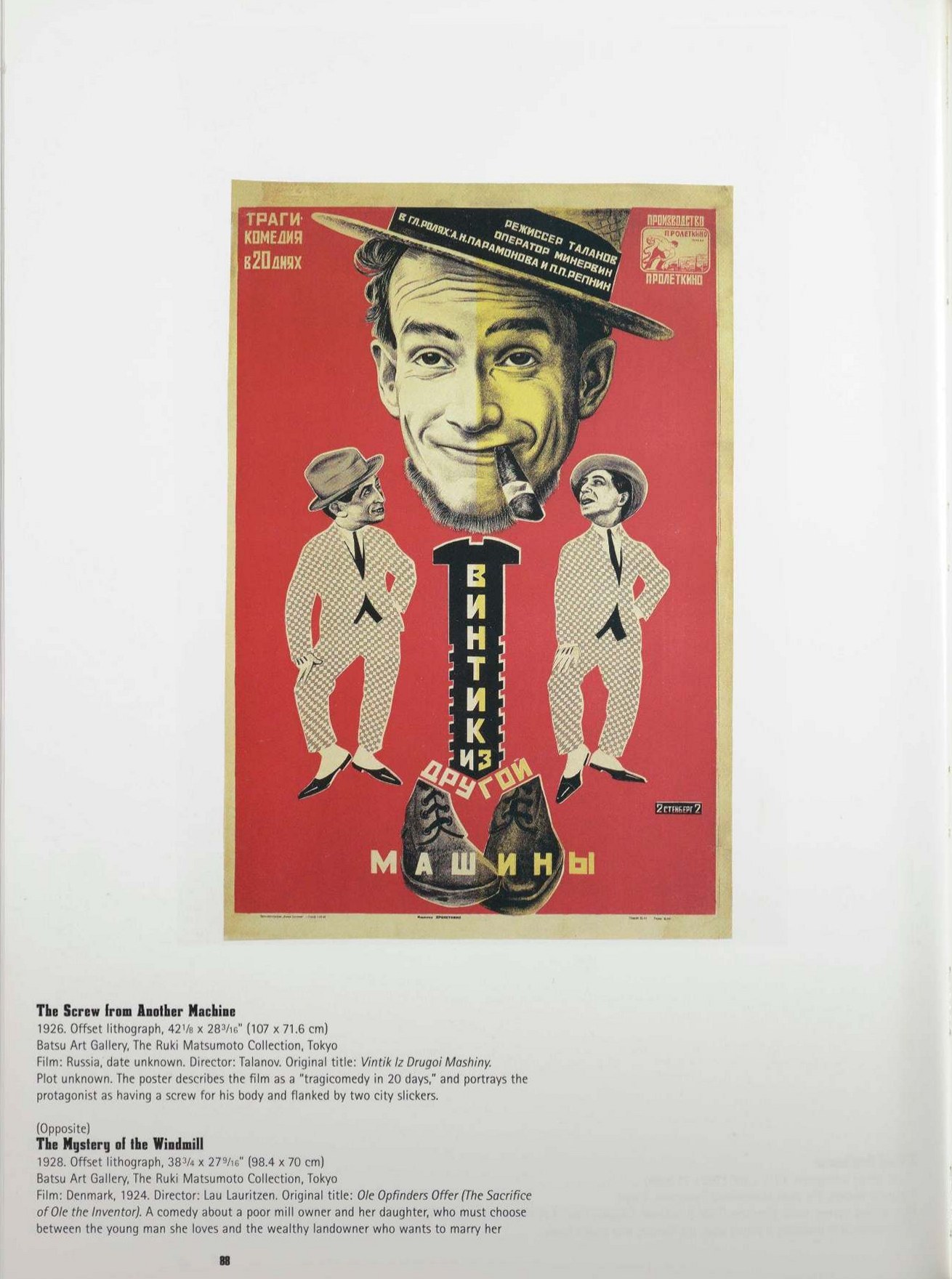

This exhibition comprises approximately 100 works, including 65 film and political posters, design sketches for the posters, journals, and stage and costume designs, as well as a small selection of the Stenbergs' early Constructivist experiments. It is the largest museum exhibition to date devoted to the work of an individual or collaborative team of graphic designers.

FOREWORD

Suffering a fate common to many of the artists and designers working in the Soviet Union in the 1920s, Vladimir and Georgii Stenberg are little known today. Like that of many members of the postrevolutionaiy avant-garde, their work fell into disfavor in the 1930s, when Josef Stalin decreed socialist realism to be the official mode of artistic representation.

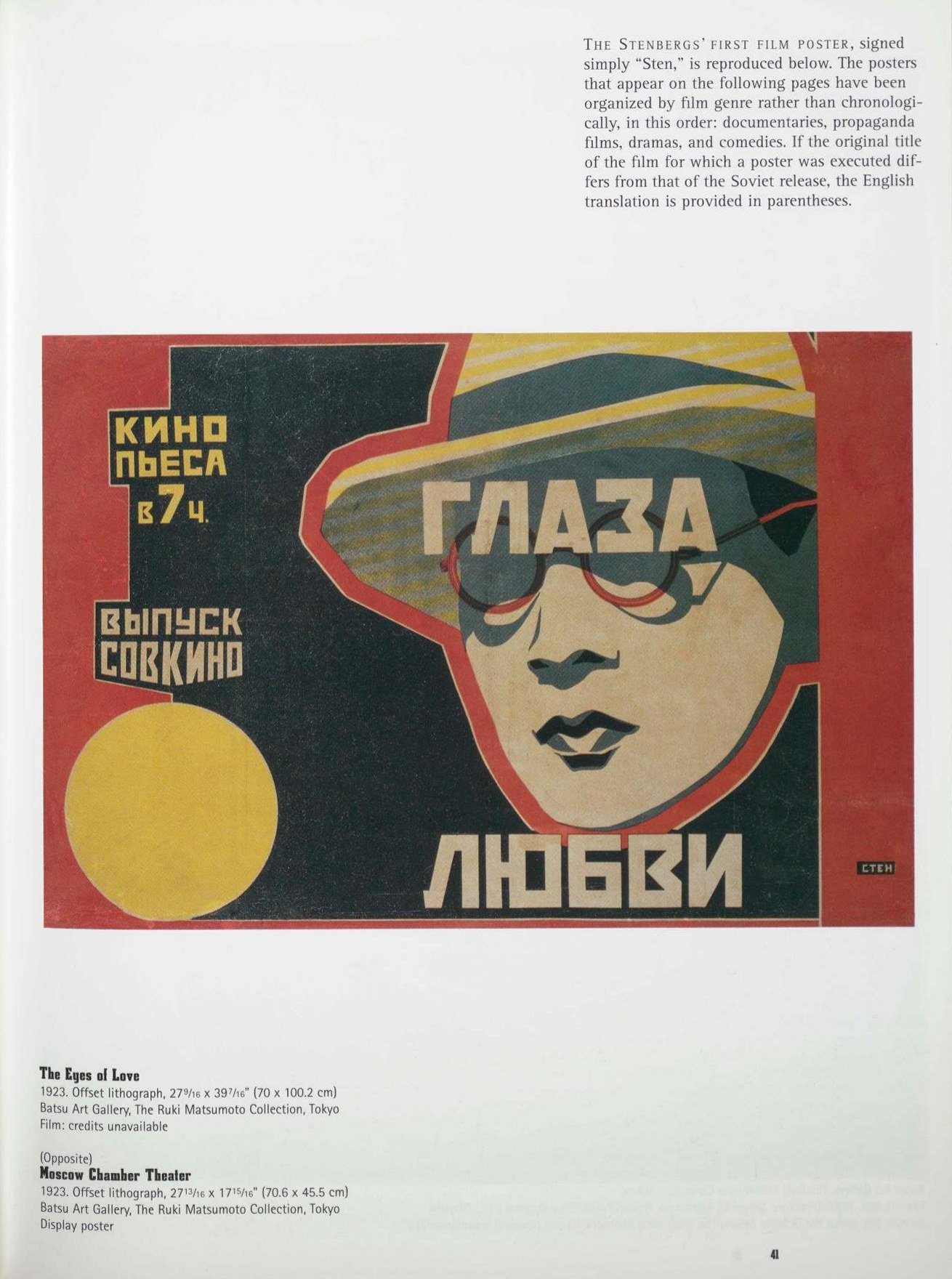

Further contributing to the Stenbergs’ eclipse was the nature of their work. Their greatest achievements were not in the fine arts but in the field of graphic design, specifically, their designs for mass-produced posters used to advertise films. For good reason, such works generally are catalogued as ephemera; cheaply printed on poor-quality paper, the posters had a singular and timely purpose. That so many examples of the Stenbergs' work survive is in itself astonishing.

The exhibition Stenberg Brothers: Constructing a Revolution in Soviet Design, organized by Christopher Mount, Assistant Curator in the Department of Architecture and Design, is the first critical survey of the work of these two seminal figures in the history of twentieth-century graphic design. While the Stenbergs’ achievements include designs for theatrical sets and costumes, books, interiors, and buildings, it is their film posters that comprise their greatest contribution to the arts of this century. The film posters most directly addressed the possibility of cultural expression in an age of mass production, melding the ethos of the machine, in their means of production, and the film, in their visual language. Transcending both functional and political boundaries, the work of the Stenberg brothers represents the best of the spirit of invention that has characterized the twentieth century.

I particularly would like to note the generosity of Ruki Matsumoto with regard to the exhibition and this catalogue. Not only has he increased The Museum of Modern Art's collection of posters by the Stenberg brothers through his gift of key works, he has lent a great many of the posters in the exhibition.

Mr. Matsumoto also underwrote the costs of the exhibition’s organization and development, as well as the costs of producing this catalogue.

Terence Riley, Chief Curator,

Department of Architecture and Design

[from Christopher Mount's essay for the catalogue accompanying the exhibition]

The 1920s and early 1930s were a revolutionary period for the graphic arts throughout Europe. A drastic change took place in the way graphic designers worked that was a direct consequence of experimentation in both the fine and the applied arts. Not only did the formal vocabulary of graphic design change, but also the designer's perception of self. The concept of the designer as "constructor"—or, as the Dadaist Raoul Hausmann preferred, "monteur" (mechanic or engineer)—marked a paradigmatic shift within the field, from an essentially illustrative approach to one of assemblage and nonlinear narrativity. This new idea of assembling preexisting images, primarily photographs, into something new freed design from its previous dependence on realism. The subsequent use of collage—a defining element of modern graphic design—enabled the graphic arts to become increasingly nonobjective in character.

In Russia, these new artist-engineers were attracted to the functional arts by political ideology. The avant-gardists' rejection of the fine arts, deemed useless in a new Communist society, in favor of "art for use" in the service of the state, was key in the evolution of the poster. Advertising was now a morally superior occupation with ramifications for the new society; as such, it began to attract those outside the usual illustrative or painterly backgrounds—sculptors, architects, photographers—who brought new ideas and techniques to the field.

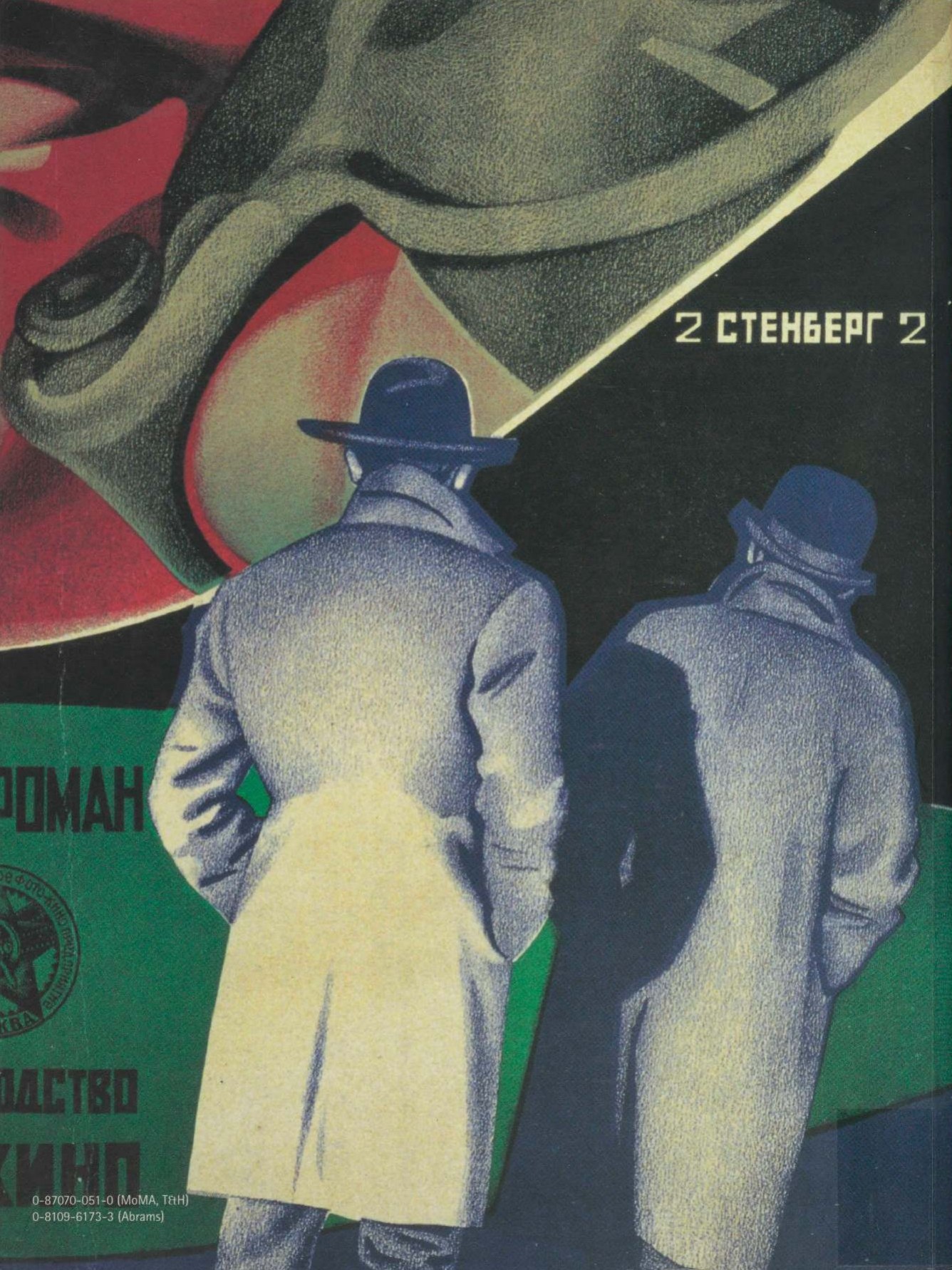

Vladimir and Georgii Stenberg were prominent members of this group, which was centered in Moscow and active throughout the 1920s and early 1930s. The Stenberg brothers produced a large body of work in a multiplicity of mediums, initially achieving renown as Constructivist sculptors and later working as successful theatrical designers, architects, and draftsmen; in addition, they completed design commissions that ranged from railway cars to women's shoes. Their most significant accomplishment, however, was in the field of graphic design, specifically, the advertising posters they created for the newly burgeoning cinema in Soviet Russia.

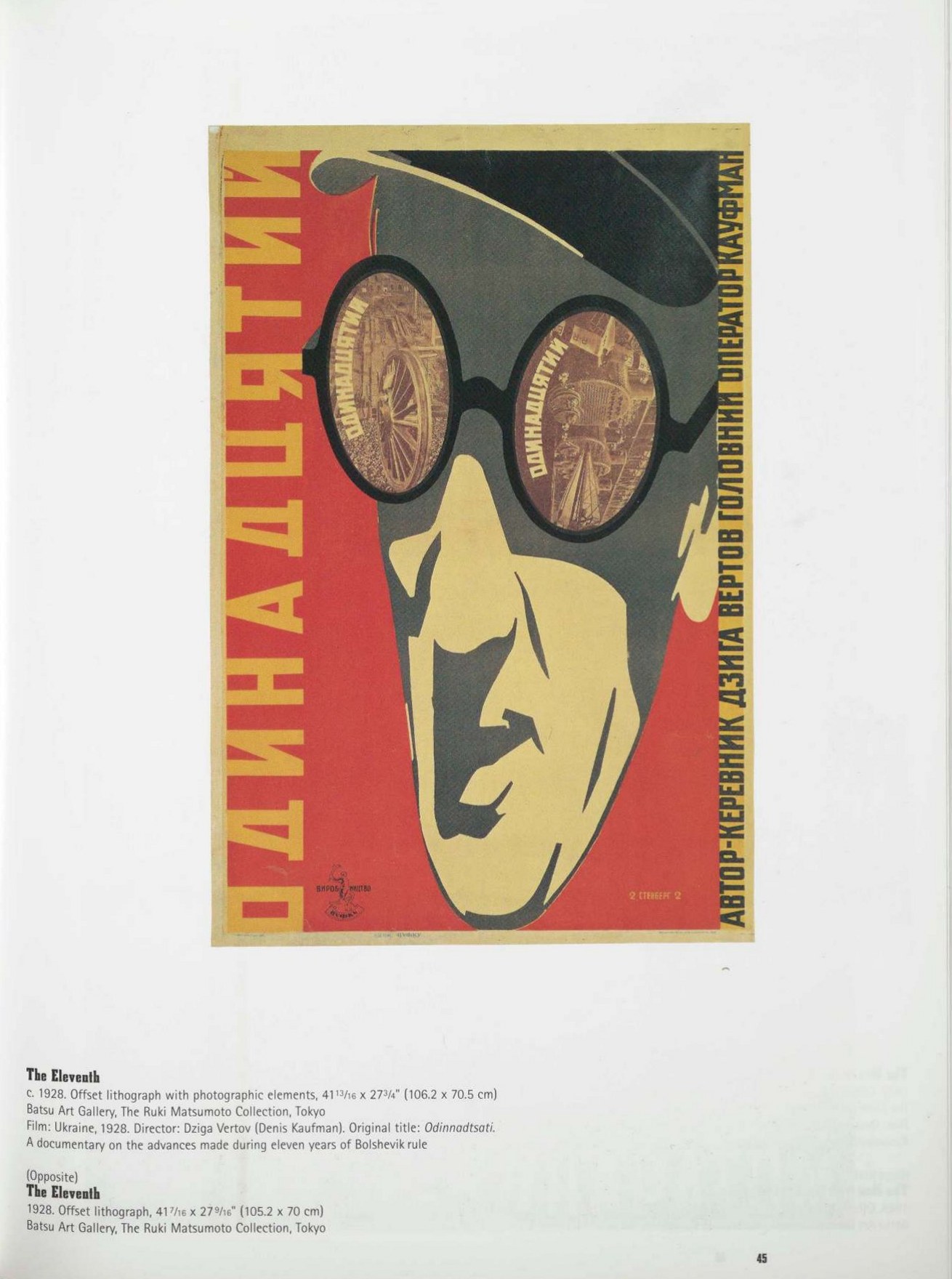

These works merged two of the most important agitational tools available to the new Communist regime: cinema and the graphic arts. Both were endorsed by the state, and flourished in the first fifteen years of Bolshevik rule. In a country where illiteracy was endemic, film played a critical role in the conversion of the masses to the new social order. Graphic design, particularly as applied in the political placard, was a highly useful instrument for agitation, as it was both direct and economical. The symbiotic relationship of the cinema and the graphic arts would result in a revolutionary new art form: the film poster.

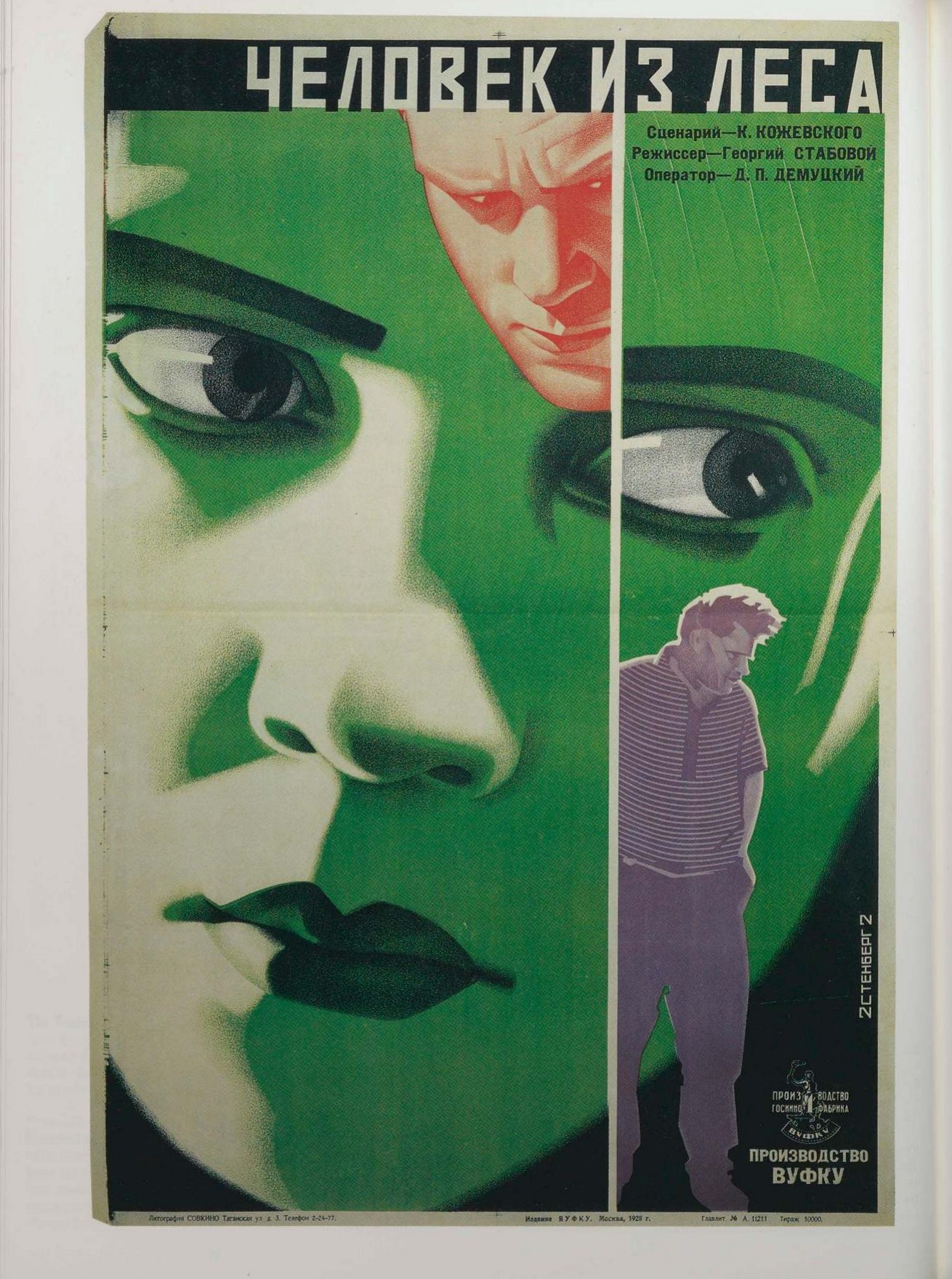

The film posters of the Stenberg bothers, produced from 1923 until Georgii's untimely death in 1933, represent an uncommon synthesis of the philosophical, formal, and theoretical elements of what has become known as the Russian avant-garde. These posters, radical even from current perspectives, are not the consequence of some brief flame of eccentric artistic creativity, but rather a consolidation of the Stenbergs' own eclectic experience—possible only in this era—and the formal artistic inventions of the time. Their intimate knowledge of contemporary film theory, Suprematist painting, Constructivism, and avant-garde theater, as well as their skill in the graphic arts, was essential to the genesis of these works.

These works, albeit of a popular genre, were revolutionary with respect to the history of design. The Stenberg's numerous innovations—the rethinking of the content of the film poster, the introduction of implied movement, the expressive use of typography and color, the distortion of scale and perspective—were subsequently investigated and extended by other designers and movements. Many of the Stenbergs' experiments with letterforms can be seen as precursors to the phototypographic advertisements of the 1960s. And their facile manipulation of pictorial space seems remarkably prescient in light of the infinite mutability of the photographic image made possible by the desktop computer only in the last ten years.

Evident in all of the Stenberg's posters is a sense of playfulness and an openness to experimentation. Often humorous, sexy, and psychologically complex, they display a confident autonomy from the dictates of commissioning studios and what would soon become a totalitarian regime—and not only in terms of their plurality of themes, an obvious reason for which is the broad range of films for which the posters were produced, from Hollywood slapstick to Soviet propaganda.

Most importantly, the Stenbergs explicitly understood the function of the poster, and their remarkable innovations, while strikingly beautiful, were clearly means to a desired end: the creation of a visually compelling work. The purpose of any poster is to attract the eye in the briefest of intervals.

CONTENTS

Foreword. Terence Riley 7

Stenberg Brothers: Constructing a Revolution in Soviet Design. Christopher Mount 10

Early Soviet Cinema Culture. Peter Kenez 22

Plates 34

Chronology. Compiled by Natasha Kurchanova 92

Acknowledgments 94

Trustees of The Museum of Modern Art 96

Sample pages

Download link (pdf; yandexdisk, 23,8 MB).

Source: moma.org

13 июня 2018, 18:28

0 комментариев

|

Партнёры

|