|

|

Theo van Doesburg. Principles of Neo-Plastic Art. — London, 1969  Principles of Neo-Plastic Art / Theo van Doesburg : with an introduction by Hans M. Wingler and a postscript by H. L. C. Jaffé ; translated from the German by Janet Seligman. — London : Percy Lund, Humphries & Co Ltd., 1969. — X, 73 p., ill.PUBLISHERS' NOTE

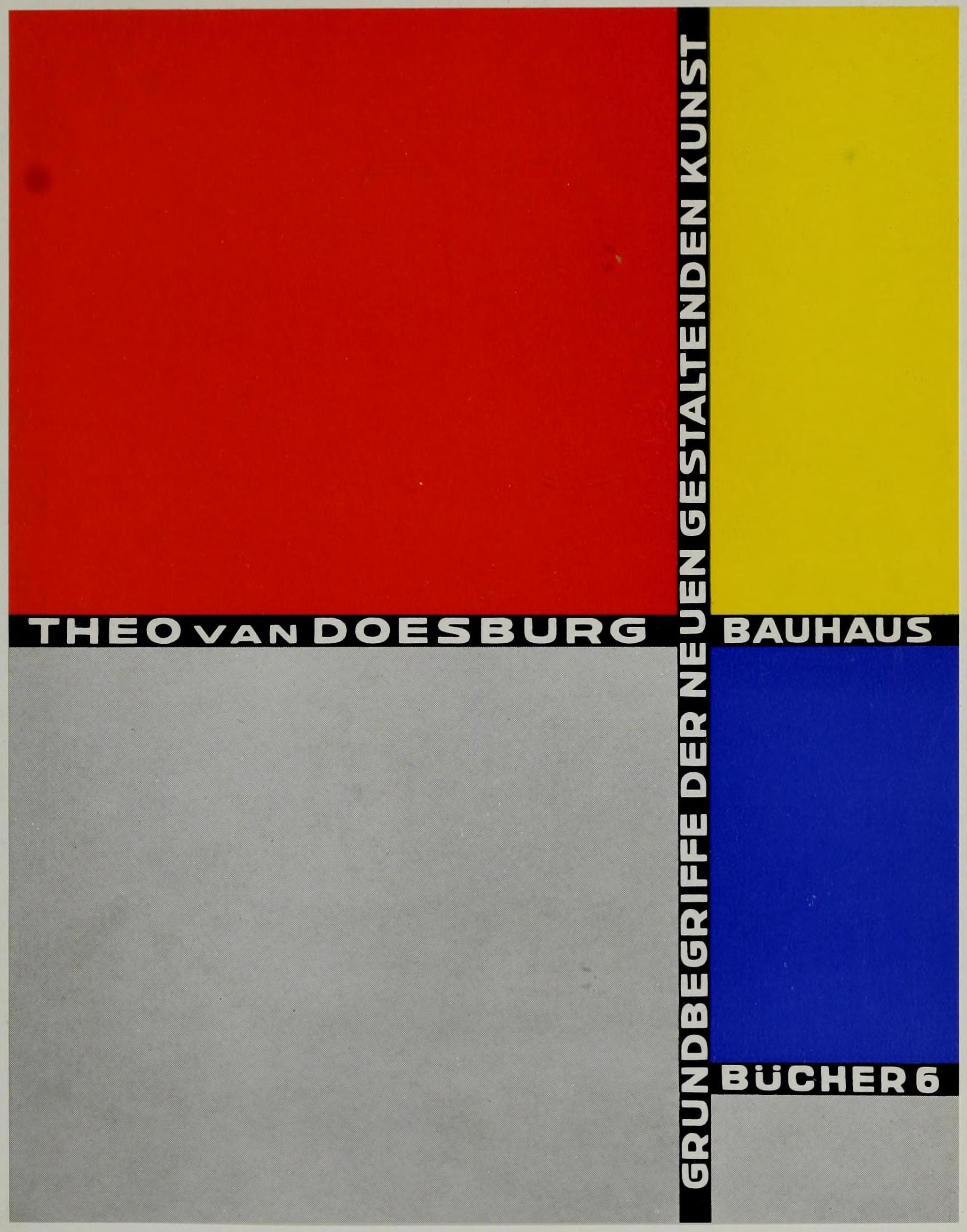

THIS IS A TRANSLATION OF GRUNDBEGRIFFE DER NEUEN GESTALTENDEN KUNST WHICH ORIGINALLY APPEARED AS VOLUME 6 IN THE BAUHAUSBÜCHER SERIES IN 1925 AND WAS REISSUED IN 1966 IN FACSIMILE (ORIGINAL TYPOGRAPHY BY LASZLO MOHOLY-NAGY) IN THE SERIES NEUE BAUHAUSBÜCHER BY FLORIAN KUPFERBERG VERLAG, MAINZ. IN AN EFFORT TO CONVEY SOMETHING OF THE TRUE FLAVOUR OF THE ORIGINAL VOLUME, AN ATTEMPT HAS BEEN MADE IN THIS ENGLISH LANGUAGE EDITION TO ADHERE AS CLOSELY AS POSSIBLE TO THE ORIGINAL TYPOGRAPHY AND MAKE UP OF THE GERMAN EDITION.

CONTENTS

VII INTRODUCTION BY HANS M. WINGLER: THE BAUHAUS AND DE STIJL

2 THEO VAN DOESBURG: REPORT OFTHE DE STIJL GROUP (1922)

3 COLOURED REPRODUCTION OF THE JACKET DESIGNED BY THEO VAN DOESBURG FOR THE 1925 EDITION OF THIS BOOK IN THE SERIES OF 'BAUHAUS BOOKS'

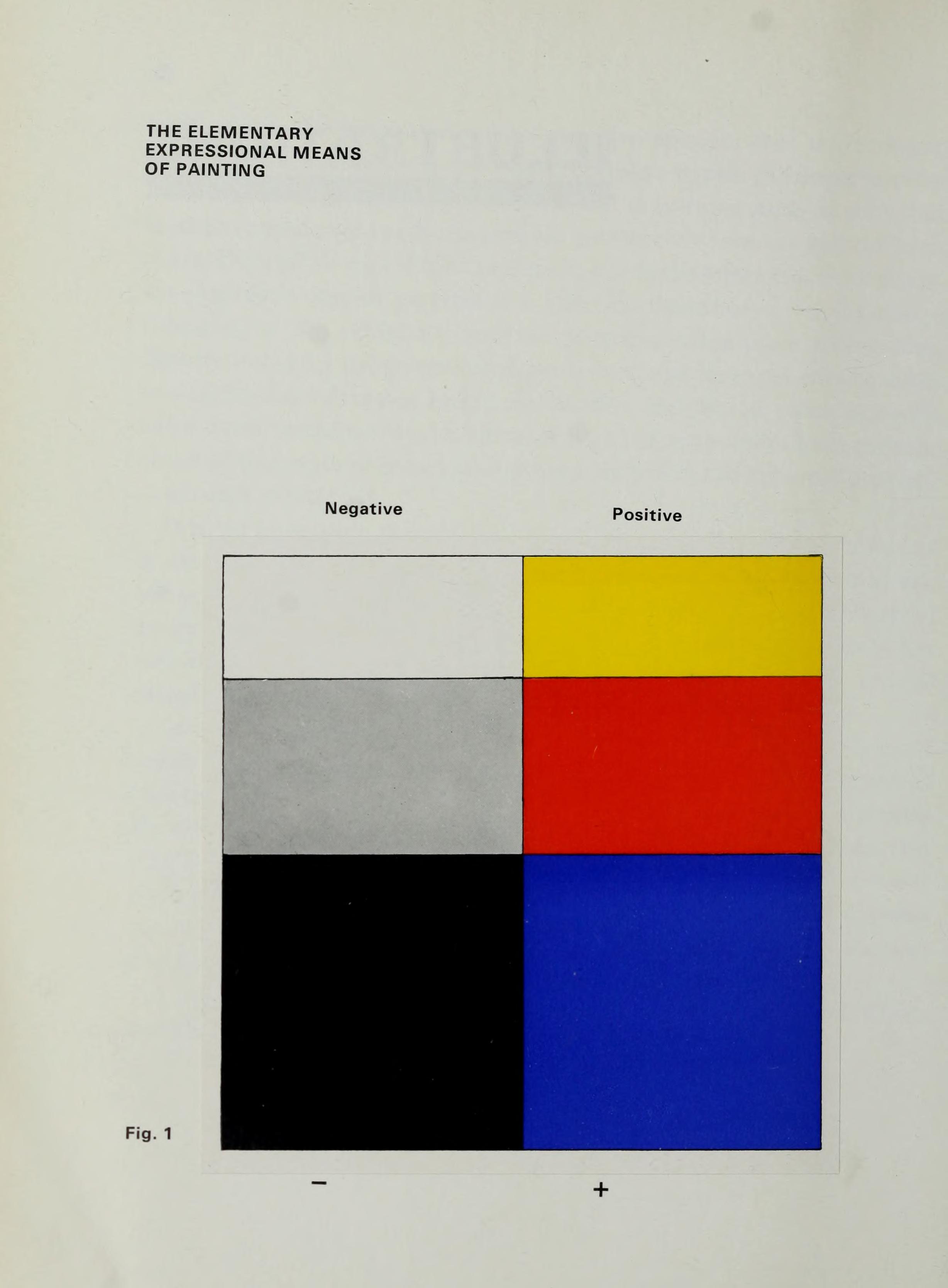

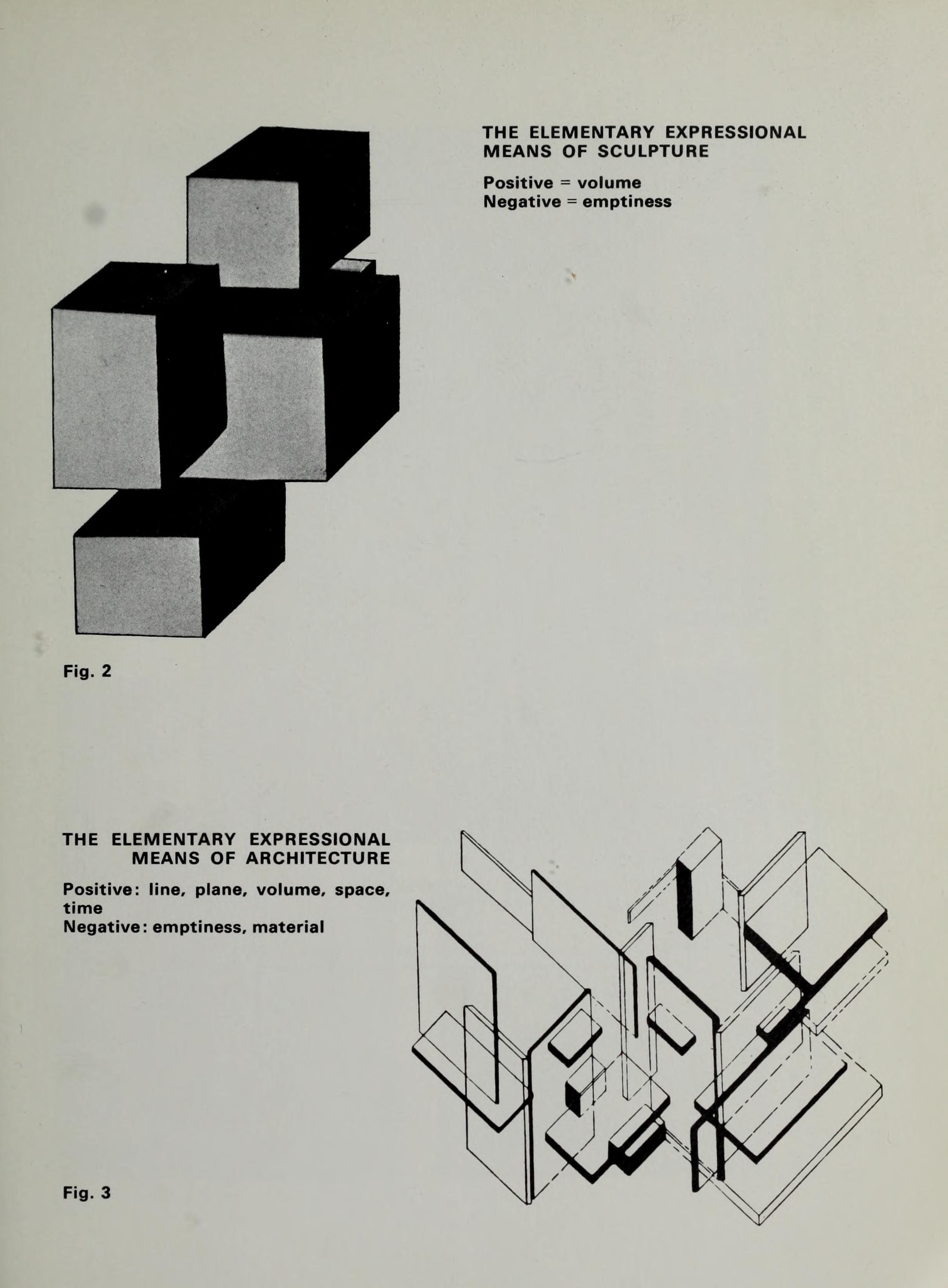

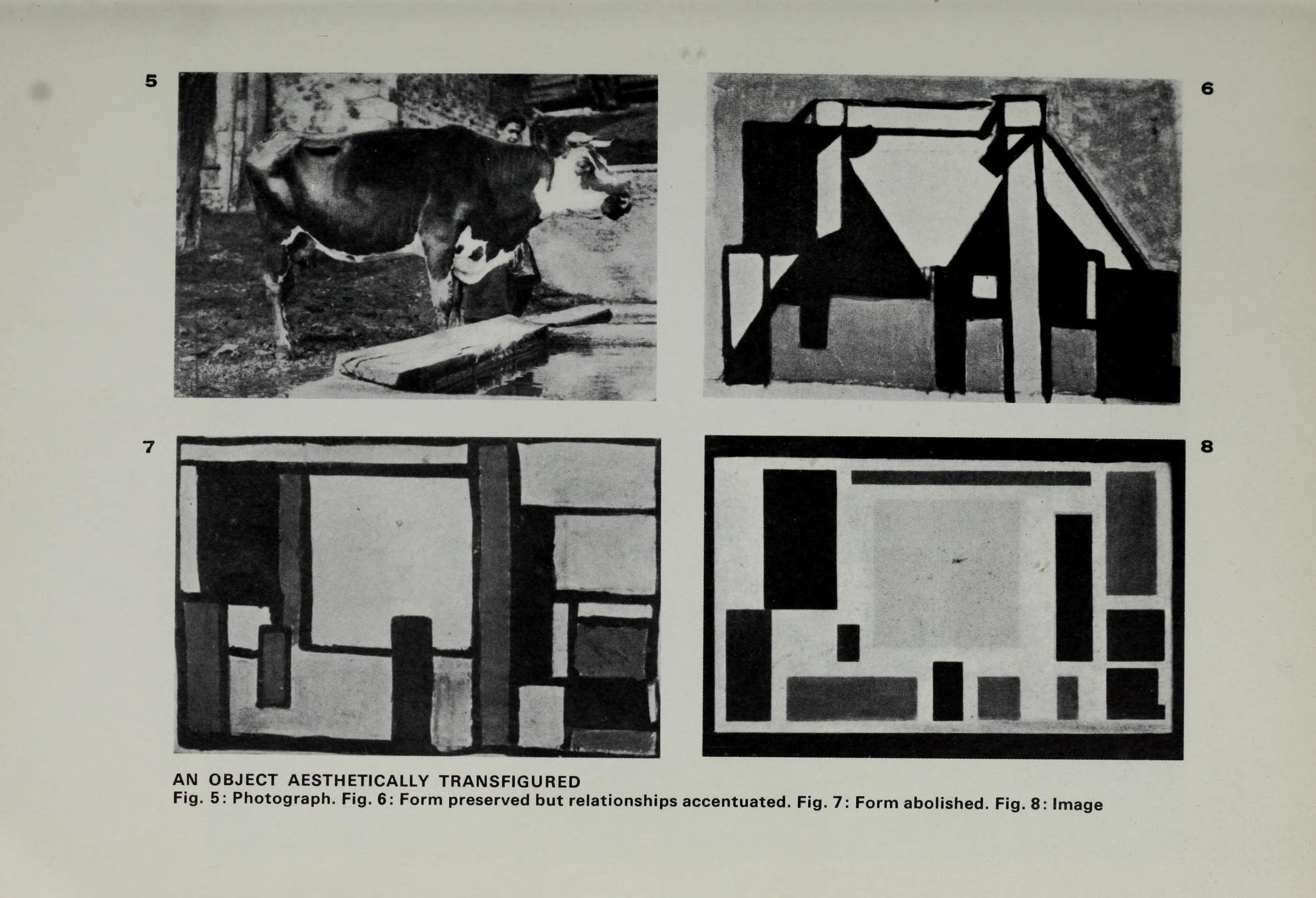

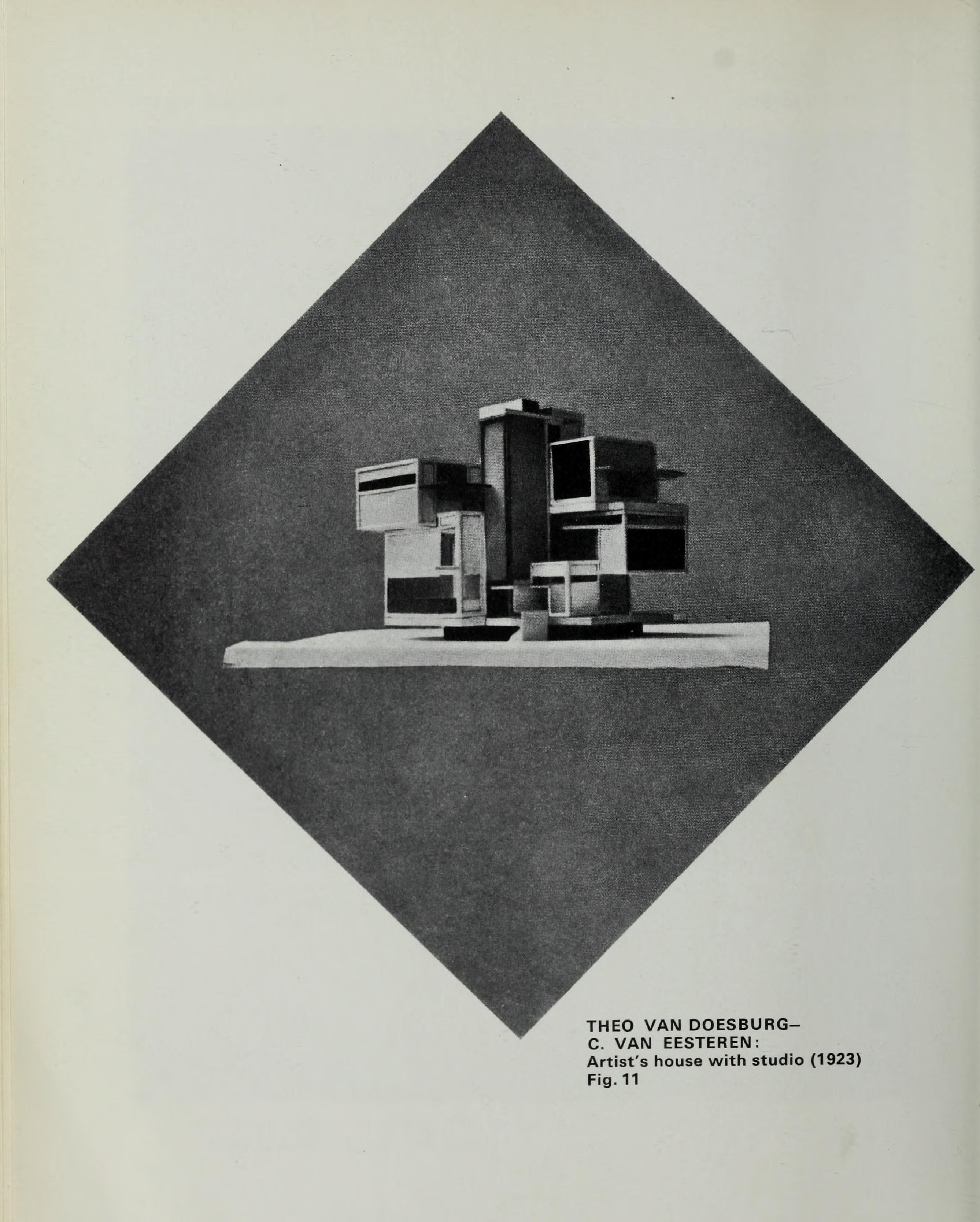

5 THEO VAN DOESBURG: PRINCIPLES OF NEO-PLASTIC ART

69 POSTSCRIPT BY H. L. C. JAFFÉ: THEO VAN DOESBURG

INTRODUCTION BY THE EDITORTHE BAUHAUS AND DE STIJL

Theo van Doesburg's Principles of Neo-Plastic Art appeared as the sixth volume of the 'Bauhaus Books' in 1925. Van Doesburg had designed the jacket himself but the typographical layout of the cloth binding and the pages of text and illustration were by Laszlo Moholy-Nagy. The book was dedicated by its spiritual father to 'friends and enemies'. A number of people doubtless already knew of its contents by hearsay and anyone who knew Dutch could have read the arguments. As we learn from a note dated 1924 which appeared over the imprint in the 'Bauhaus Book', Van Doesburg had completed the 'original manuscript' by 1917, from notes made in 1915 ; it had been printed in two numbers (Volumes I and II) of the philosophical journal Het Tijdschrift voor Wijsbegeerte. 'My purpose', continues Van Doesburg in his note, 'was to answer the fierce attacks made by the public with a logical explanation and a defence of the new plastic art. I owe it to my stay in Weimar and to the assistance of my friend Max Burchartz that this thoroughgoing German translation was made in about 1921–1922... I have simplified and revised many passages during the course of translation.'

Van Doesburg was at Weimar for about two years and his stay there occasioned a number of speculations about his relationship with the Bauhaus, with which, apparently, he was anxious to make closer contact, of which he was a rival and which he is supposed to have influenced. Relations – sometimes strained – did indeed exist. So strong was the fascination exerted by Theo van Doesburg that he gathered round him a few Bauhaus students – undoubtedly gifted men – who felt more powerfully drawn by talks with him than by the course. Forming as they did a Fronde, they were a fairly seriously disturbing factor and it was therefore not surprising that the Council of Masters of the Bauhaus looked upon visits to Van Doesburg with disfavour. Nevertheless, in matters of fundamental artistic importance there was a large measure of agreement between the two sides. That none of the views on art proclaimed by Van Doesburg and the De Stijl group was basically different or more advanced than those of the founder of the Bauhaus is demonstrated by a glance at Gropius's early buildings: the importance of the Fagus factory at Alfeld (1910–11) and the buildings at the Werkbund exhibition in Cologne (1914) and the key-position they occupy have never been in doubt.

Van Doesburg discusses the arguments which went on in Weimar during the 1920's between De Stijl and the Bauhaus in a letter written from Meudon on 1 May 1924 and addressed to Molohy-Nagy, with the request that it be passed on to the Council. In this letter – which is preserved in the Bauhaus Archive – Van Doesburg states in his somewhat awkward style – German was not, of course, his native tongue – that as soon as he had become acquainted with the Bauhaus and its artistic activity ... he had been extraordinarily interested. 'In so far as its efforts ran parallel with similar efforts in Holland which had already been tried out in practical building, I wanted – although my purpose was not in the least personal – to take up the fight with my artistic work and my propaganda independently of the Bauhaus and to support the administration (of the Bauhaus) in its struggle.' When in 1920 Gropius first saw photographs of work by members of the De Stijl group, he recognized the convincing maturity of their achievements but at the same time stressed that he wished in all circumstances to keep the Bauhaus free of 'dogmas' so that everybody could develop 'his own creative individuality'. This showed that although there was agreement on questions concerning art, there were differences in didactic method which promised a poor look-out for direct collaboration at the same teaching establishment.

Once settled in Weimar, Van Doesburg wrote again that his picture of the Bauhaus had soon been dimmed, for 'My home Am Horn and later my studio Am Schanzengraben became meeting-places for people who criticized and found fault most bitterly with the internal structure of the Bauhaus (of which I knew nothing). These critics were not only enemies of the Bauhaus but also friends, masters, pupils...' Instead of having to listen to troubles and gossip-mongering of an all too personal nature. Van Doesburg would have preferred to have held open discussions with the Bauhaus on questions of art. Everyone knew, he said, that, sharp though his criticism had been, it was 'aimed solely at purely artistic differences and differences over principle in the Bauhaus and that its starting-point had always been the basic programme and nothing else'.

There were, indeed, contradictions between Bauhaus programme and practice. Although Van Doesburg as an outsider could scarcely have known this, most of them resulted from the financial and political difficulties experienced by an institution dependent upon the state and upon the good will of a citizenry of largely conventional outlook. This explains the 'impossibility of achieving the collective complete building', which required for its construction not only intellectual preparedness, but also material conditions which simply did not exist. But Van Doesburg's criticism did touch a tender spot in the inner administration of the Bauhaus when he reproved it for allowing metaphysical speculation and religious sectarianism to side-track or overlay the 'real problems of Gestaltung'. The special butt of this criticism seems to have been Johannes Itten's circle. In the pathos of Expressionism (which had, indeed, already been evident in the founding manifesto of 1919), the Bauhaus had to some extent departed from aesthetic clarity and from the relevance to both life and function found in the early work of its founder. Theo van Doesburg's criticism supported Walter Gropius – who seems to have been totally unaware of the assistance that was being proffered – in his attempts to realize, in the great co-operative achievement that was the Bauhaus, those ideas which were most his own and had preoccupied him since as early as about 1910, and on which he had worked unremittingly since then. Van Doesburg's presence worked now to some extent as a catalyst which precipitates reaction in a chemical substance but does not amalgamate with it. Gropius remained entirely himself. There were only two fields in which De Stijl examples palpably influenced the Bauhaus – typography and furniture design. Thus Marcel Breuer's first chairs (these were still made of wood) are formally derived from works by the Dutchman Rietveld. Nevertheless the number of suggestive ideas which were actually turned to practical account is small.

Important as was the critical self-consideration that was now going on in the Bauhaus, the tremendous psychological tensions which in about 1921 had almost burst asunder the combined ranks of teachers and pupils produced many inhibiting effects but also far-reaching constructive ones. This should not be forgotten. When Klee likened the Bauhaus to a 'play of forces' and praised it for being such, he was looking upon it as a field of tension; similarly Muche in his reminiscences calls it an 'accord' which he emphatically wishes to be certain is not confused with smooth 'harmony'. This special ability of the Bauhaus community to heighten the most specifically personal qualities of the individual members and to permit them to develop – always to the advantage of the group – had evolved out of crises and never failed to affect sensitive visitors who had the opportunity to look below the surface. We may surely assume that – once the situation had been clarified – Theo van Doesburg too sensed this and that it helped to persuade him to correct his radical attitude towards the Bauhaus, which, as he stressed, despite certain individualistic features was certainly no 'academic sleeping-powder' and no 'artificial preserve tin'. Had he not respected the distinctive intellectual quality of the Bauhaus, it is difficult to imagine how – from the point of view of either side – his Principles of Neo-Plastic Art could have appeared in the series of 'Bauhaus Books'.

Other artists of De Stijl were in touch with the Bauhaus in the way of collaboration. Mondrian had a large coloured lithograph printed at the graphic printing works of the Staatliches Bauhaus; Oud gave a lecture on 'The development of modern architecture in Holland' on the occasion of the 'Bauhaus week' in August 1923. Both wrote 'Bauhaus Books' – Mondrian a volume of essays on New plastic art. Oud a collection of short studies entitled Dutch Architecture. It was a matter of course for the friends of the Bauhaus in the De Stijl group to stand out solidly for the Bauhaus when it was slandered and attacked. But even then, for all the friendly understanding, the possibility of distance was taken for granted. For despite everything they had in common. De Stijl and the Bauhaus were and remained opposed to one another in one all-important essential. De Stijl, as its name implies, demanded style, stylistic form, an entirely specific mode and manner of artistic manifestation which, it was hoped, would gain universal allegiance. Gropius and his fellow combatants rejected any fixation upon one stylistic theory and had no wish to create a 'Bauhaus style'. To the teachers at the Bauhaus it appeared more important than formal results that their pedagogical work should succeed in developing the personality in the awareness of its responsibility to art, a responsibility which was also to be regarded as social.

As editor of this book I thank Frau Nelly van Doesburg (Meudon), who has continued to promote her husband's ideas, and Professor Jaffé (Amsterdam), the interpreter of De Stijl, for their advice and active collaboration.

H. M. WINGLER

Theo van Doesburg's signature

THEO VAN DOESBURGREPORT OFTHE DE STIJL GROUP

vis à vis the 'Union of International Progressive Artists'

at the 'International Artists' Congress' in Düsseldorf,

29 to 31 May 1922 (fragment)

I. I speak here for the De Stijl group in Holland which has arisen out of the necessity of accepting the consequences of modern art; this means finding practical solutions to universal problems.

II. Building, which means organizing one's means into a unity (Gestaltung) is all-important to us.

III. This unity can be achieved only by suppressing arbitrary subjective elements in the expressional means.

IV. We reject all subjective choice of forms and are preparing to use objective, universal, formative means.

V. Those who do not fear the consequences of the new theories of art we call progressive artists.

VI. The progressive artists of Holland have from the first adopted an international standpoint. Even during the war...

VII. The international standpoint resulted from the development of our work itself. That is, it grew out of practice. Similar necessities have arisen out of the development of... progressive artists in other countries.

(Printed in de Stijl, Volume V, 1921–2, page 59)

DEDICATED TO FRIENDS AND ENEMIES

The original manuscript was completed in about 1917 from notes made as long ago as 1915 and printed in ‘Het Tijdschrift voor Wijsbegeerte’ (Journal of Philosophy, Vols. I and II). My purpose in writing it was to answer the fierce attacks made by the public with a logical explanation and a defence of the new plastic art. I owe it to my stay in Weimar and to the assistance of my friend Max Burchartz, that this thoroughgoing [German] translation was made in about 1921–2. I tender him my most hearty thanks! I have simplified and revised many passages during the course of translation.

Paris 1924.

Introduction

One of the most serious of the many reproaches levelled against modern artists is that they address themselves to the public not only through their works, but through their words as well. Those who reproach the artist for so doing forget, first, that there has been a shift in the relationship of the artists to the community – a shift, that is, in social consciousness – and, second, that the fact that the artist writes and talks about his work is the natural outcome of the general misunderstanding of the manifestations of modern art on the part of the laity. Because the works lie outside the limits of the awareness of many contemporaries, it is they themselves who beg the artist to explain them. These questions – be they seriously or ironically intended – have made it a matter of conscience for artists to intercede verbally on behalf of their works.

This is the source of the misconception that the modern artist is too much of a theoretician and that his work springs from a priori theories. In fact, precisely the opposite is the case. The theory came into being as the necessary consequence of creative activity. Artists do not write about art, they write from within art.

The upshot, in fact, has been this: the artists have required of their artistic theory the same as they have required of their work: exactitude. It is this that has given their utterances their rigorously abstract character. This is a gain which ought not to be underestimated, yet it has the drawback that for most laymen this kind of introduction is almost as difficult to understand as the work itself. Consequently this manner of elucidation failed of its practical purpose.

Responsibility for present-day non-comprehension of the visual arts lies as much with the artist-theoretician as with the observer: the observer, because art is for him a matter to which he probably does not give so much as a few moments’ thought daily and because from the first he has had no doubt that art gives pleasure but demands no effort whatever.

The artist-theoretician, because only rarely is he concerned with anything apart from art and he takes the point of view that it is not for him to descend to the level of the public (which is, of course, unnecessary, indeed impossible, where his creative work is concerned), but for the public to aspire to his.

Yet how is the public to lift itself to the artist’s level if the artist does not help ; if, in other words, the artist does not help the public to see, hear, and understand his works.

The public has its own, proper interior and exterior worlds, the artist has others. The two differ so greatly that it is impossible to pass from the one to the other.

The artist speaks from within his interior and the exterior worlds in words and images which come easily to him because they are elements of the world in which he alone belongs. The public’s worlds, however, are totally different and the words with which it expresses its ideas are entirely characteristic of its own world.

The perceptions of different people, each of whom inhabit different interior and exterior worlds, clearly cannot coincide. Examples will follow. Suffice it now to show how even a single phrase used by people of different environments gives rise to totally different interpretations.

The modern artist uses the phrase ‘space formation’ in order to enable the observer to look at his work. The artist whose occupation consists in space formation and is closely involved with it, regards this expression as as much a matter of course as does the surgeon the word fracture. The layman, however, has totally different conceptions of space and formation. At best he takes ‘space’ to mean a hollow or a measurable surface. The word ‘formation’ will awaken in the observer an uncertain memory of a physical shape. The combination of the two words ‘space’ and ‘formation’ will therefore convey to him a physical form having spatial depth and shown in perspective in the manner of the artists of the past.

To the modern creative artist space is not a measurable, delimited surface, but rather the idea of extent which arises from the relationship between one means of formation (e.g. line, colour) and another (e.g. the picture plane). This idea of extent or space touches the fundamental laws of all the visual arts because the artist must understand its principles. Furthermore, space means to him a special tension created in the work by the tightening of forms, planes or lines. The word formation means to him the visible embodiment of the relationship between a form (or colour) and space and the other forms or colours.

As we can see, the two interpretations differ greatly. If, as this suggests, there is so great and fundamental a difference between the artist and the layman in their understanding of a single phrase, it will be impossible for the layman to grasp those numerous concepts which would enable him to advance towards an understanding of the work of art itself.

This, however, applies not only to the layman but also to those concerned in one way or another with the visual arts.

If confusion of ideas in the terminology of the visual arts were the sole cause of lack of understanding and misinterpretation, the remedy would be easy; unfortunately, however, there are other difficulties which hinder understanding.

Another cause must be sought in the following fact: since the old ideas of the visual arts have become outmoded and are no longer valid, a new groundwork of ideas is needed, or, perhaps, a new system of instruction to give the layman a new point of view and to clarify his ideas or completely reconstitute them. Just as Spanish flies are no longer prescribed in medicine, so in painting it has become impossible to cling to a Vitruvian hypothesis.

Vitruvius says in the Sixth Book of his work on architecture: ‘A painting is the representation of a thing which exists or which can exist, e.g., a man, a ship or other things for which rigidly outlined physical forms have served as models.’

Experience proves that this idea still persists, both among laymen and among many artists too. With so primitive a conception of art many good articles and books about the new visual art must inevitably fail to bring proper results*). All these studies (most of them by art-historians) evince too personal an interpretation. These writings are the products of a system of thought and feeling which has an individualistic bias and as such are not suited to elucidate a creative principle rooted in universality. Personal interpretation of the various expressional forms of the new visual art must be replaced by a synthesis of its nature, which alone can answer the purpose.

____________

*) The works which have appeared in Germany, France, Italy and America on the new visual art amount to a considerable volume of literature on this question.

One of the most significant points of difference between it and earlier concepts of art consists in the fact that in the new art the artist’s temperament is no longer so prominent. The new plasticism is the product of a universal stylistic intent.

Daily intercourse with serious modern artists has convinced us that they are not concerned to bring their personalities to the fore or to force their personal ideas upon any one. Basically, their sole purpose is to produce works which shall be as good as possible; and to draw closer to the public through their writings so as to promote mutual understanding between the artist and the community. Obviously this cannot be achieved without great difficulties, but these could be overcome were it not for a third cause which makes it almost impossible for the artist to address himself to the public, either directly through his work or indirectly by explanation.

This third cause is official newspaper criticism. It derives from the extremely sketchy and subjective impressions of a few, mostly unintelligent, lay people who possess an outmoded or hazily modern conception of painting. What this criticism lacks is method. When criticism of works of art lacks method, confusion must inevitably arise over the meaning of the modern visual art – for the personal impressions of Messrs A. and B. can render the public but little assistance.

We have already repudiated this habit of reviewing works of art instead of elucidating them. Those who enjoyed doing so we called lay critics, not in order to offend them, but to define their true relationship to art and to the public.

This type of art review should be rejected. First, because the artist, rather than the work of art, becomes the object of the review and secondly and, indeed, mainly, because a universally acceptable concept of ‘formation’ (Gestaltung) and ‘art’ – and therefore any critical method – is alien to all these critiques.

The modern artist desires no intermediary. He wishes to address himself to the public directly, through his work. If the public does not understand him it is up to him to provide his own explanations.

The main reason why the public is on the wrong tack where the new art is concerned lies in the irrelevance of lay criticism, which obscures with unclear clarifications the unprejudiced vision and experience of works of art.

There is only one way to restore the unprejudiced way of looking, destroyed by the ignorance and complacency of traditional art criticism: elementary and universally intelligible principles of visual art must be established — which is what is attempted here.

Sample pages

Download link (pdf, yandexdisk; 41 MB)

9 июня 2023, 13:24

0 комментариев

|

Партнёры

|

Комментарии

Добавить комментарий