|

|

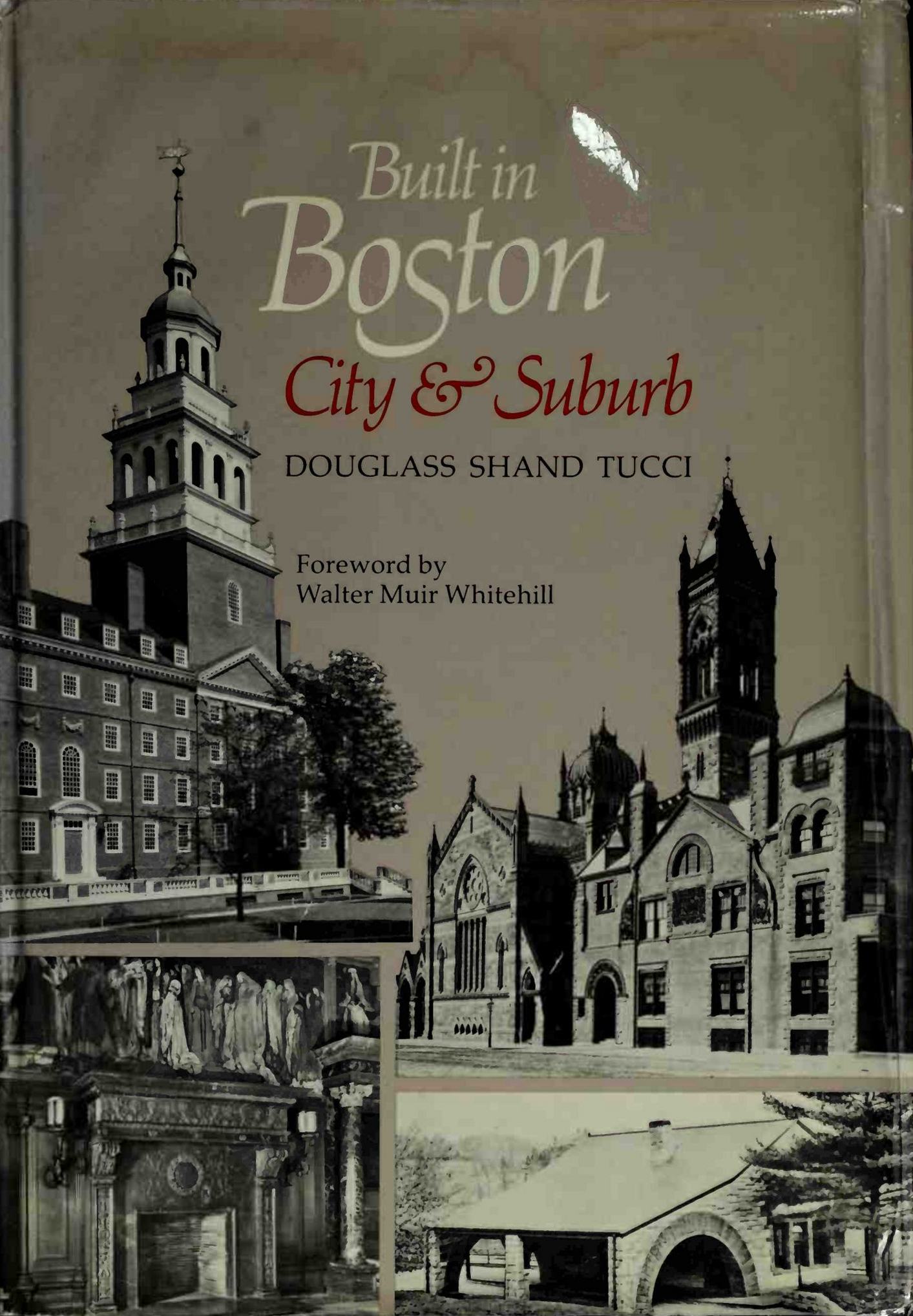

Tucci D. Sh. Built in Boston: City and Suburb. 1800—1950. — Boston, 1978Built in Boston: City and Suburb. 1800—1950 / Douglass Shand Tucci ; With a foreword by Walter Muir Whitehill. — Boston : New York Graphic Society, 1978. — XVIII, 269 p., ill. — ISBN 0-8212-0741-5

In the imagination of the world Boston holds a secure place. Readers far and wide will welcome this first full-length history (as opposed to guide) of Boston's architecture, from Charles Bulfinch to Walter Gropius. It is also the first Boston book that deals at some length with the Victorian suburbs as well as with the city proper, and that treats seriously not only late nineteenth-century design but also Boston's early Modernist architecture and its twentieth-century Classical, Gothic, Colonial, and Art Deco buildings.

The great landmarks of the city, like the Boston Public Library, are viewed in the light of a provocative reappraisal of Boston's late nineteenth-century cultural history. They are placed in the often surprising context of long-forgotten but fascinating buildings and neighborhoods rediscovered by Mr. Tucci: he examines, for instance, the apartment house, the parish church, and the movie palace—three building types in the evolution of which Boston played a key role. Mr. Tucci reminds us that Boston architecture includes America's first apartment house, first free municipal public library, first supermarket, and first subway system; that Boston played an important part in the turn-of-the-century Gothic and Classical revivals; and that roots of the Chicago Style are found in the city's innovative nineteenth-century buildings.

Lavishly illustrated in both color and black and white, including many photographs, plans, drawings, and maps made especially for it as well as older photographs never before published, Built in Boston also contains invaluable source material. The bibliography, arranged according to neighborhoods, towns, and cities of the metropolitan area, buildings, building types, architects, and craftsmen, is the most extensive one on Greater Boston architecture in print.

ForewordWALTER MUIR WHITEHILL

The two days before Christmas 1977 will stick in my memory because of the pleasure that I had in reading the manuscript of Douglass Shand Tucci's Built in Boston: City and Suburb. The book moves so skillfully from one thing to another that it is difficult to put down. One wants to find what is coming next. Moreover, several chapters, based on the author's research in previously unexplored areas, offer new material and ideas of great interest.

Last year I contributed an introduction to Architecture Boston, an excellent book produced by the Boston Society of Architects with text by Joseph L. Eldredge, F.A.I.A., which carries the reader around central Boston, Charlestown, Roxbury, and Cambridge of the present day, explaining skillfully what is to be seen there. As it is a publication of the Boston Society of Architects, it rightly gives considerable space to the work of the years since World War II. Built in Boston proceeds on chronological rather than geographical lines, undertaking to show what happened architecturally in Boston at different periods from the late eighteenth century, and why. Thus Mr. Tucci often discusses buildings that have disappeared or fallen out of general esteem or even good repair, like some of the twentieth-century theaters.

Writing in 1945 in Boston after Bulfinch: An Account of its Architecture, 1800—1900, the late Walter H. Kilham, F.A.I.A., observed: "Writers on architecture have usually avoided saying very much about the work of the nineteenth century, especially in the United States, but as a matter of fact this era of rapid expansion provides in its architecture a highly instructive picture of the developing culture of the nation."

At the beginning of the nineteenth century the practice of architecture was considered to be within the grasp of any literate gentleman who had a mind to try his hand at it. When Charles Bulfinch returned from a "Grand Tour" in 1787, he settled in Boston, "pursuing no business but giving gratuitous advice in architecture," derived from his travels, as an accommodation to his friends. When financial reverses made employment necessary, Bulfinch turned to the serious practice of architecture, and within a few years transformed the face of his native town. Another Bostonian, fifty-five years younger than Bulfinch, Edward Clarke Cabot, who had raised sheep in Illinois and Vermont, stumbled into architecture by winning in 1846 the competition for a new building of the Boston Athenaeum. In his late twenties at the time, he had not been in Europe. However, he had looked at books owned by the Athenaeum to some purpose. Although Cabot's brown sandstone facade was obviously of Italian Renaissance inspiration, it only dawned on me last year, when I was writing the catalogue for the American showing of the Palladio exhibition, that it was derived from Palladio's Palazzo da Porta Festa in Vicenza. When I found among the early nineteenth-century holdings of the Athenaeum a copy of Ottavio Bertotti Scamozzi's great folio Le Fabbriche e i Disegni di Andrea Palladio (Vicenza, 1776), in which the facade of that palace figures as plate seven in volume one, then the source of Cabot's inspiration became clear.

During the third quarter of the nineteenth century, architecture in Boston began to assume the air of a profession, as those who wished to practice it sought formal training, rather than relying on travel, books, or apprenticeship in an existing office. The sixteen-year-old Richard Morris Hunt, having been taken to Paris by his family soon after his graduation from the Boston Latin School in 1843, studied at the Ecole des Beaux Arts and worked under Hector Martin Lefuel, who was engaged upon additions to the Louvre and the Tuileries. Returning to the United States after nine years, Hunt opened in New York in 1858 a studio in which he trained younger men in the principles of architecture he had been taught in Paris. William Robert Ware, graduated from Harvard College in 1852, and Henry Van Brunt of the Harvard class of 1834 studied architecture in New York with Hunt, while Henry Hobson Richardson of the Harvard class of 1839 went to Paris to the Ecole des Beaux Arts to get French training at first hand. Ware and Van Brunt, who established a partnership in Boston in 1863, created an atelier in their new office for students on the order of Hunt's. This was so successful that in 1863 Ware was charged with the establishment of an architectural school in the recently founded Massachusetts Institute of Technology. This outstanding new school, which for the first time in the United States offered training in design according to the method of the Ecole des Beaux Arts, caused Ware in 1881 to be invited to found a similar school of architecture at Columbia University.

The American Institute of Architects was established in New York in 1857. A decade later the Boston Society of Architects was organized to seek "the union in fellowship of all responsible and honorable architects and the combination of their efforts for the purpose of promoting the artistic, scientific, and practical efficiency of the profession." Edward Clarke Cabot, who, after his success in the Boston Athenaeum competition, continued to practice architecture, was president of the society from 1867 to 1896, and thereafter honorary president until his death in 1901.

At the beginning of the nineteenth century Boston was a seaport, whose 24,397 inhabitants were almost entirely of English origin. At the end of the century, it was a polyglot industrial city of 560,892. Half of the 1900 population was Irish. A fifth hailed from the Maritime Provinces. Because of the considerable number of immigrants from Russia, Italy, Germany, and other countries, less than 11 percent were what might be considered traditional New Englanders. Even the landscape was changed during the nineteenth century by means of great landfilling operations, undertaken to make room for the burgeoning population. These changes, combined with those in the practice of architecture, make the nineteenth-century buildings of Boston "a highly instructive picture of the developing culture of the nation," as Walter Kilham noted.

In the third of a century since the publication of his book, a generation of younger architectural historians discovered the joys of nineteenth-century buildings, admiring things that their parents either ignored or ridiculed as eyesores. Ware and Van Brunt's Memorial Hall at Harvard is a case in point, although the Harvard Corporation has not yet been persuaded to restore its tower to its original splendor. The neighborhood of Quincy Market, in jeopardy not so many years ago, has been rescued by the Boston Redevelopment Authority, and is alive with people. The publication of Bainbridge Bunting's Houses of Boston's Back Bay in 1967 caused many Bostonians to realize that these buildings were not only the places where their relatives had lived but remarkable examples of nineteenth-century architecture. Mr. Tucci carries his exploration through the first four decades of the twentieth century to the point where the migration of Walter Gropius to Harvard caused an abrupt change in Boston architecture. Now that there is increasing boredom with the austerities of the "International Style," which has moved from avant garde to "old hat," it is worth reexamining the traditional architecture that it replaced.

Built in Boston naturally discusses many familiar buildings that have been studied by others, but a good half of the book is based upon its author's personal research and observations. Mr. Tucci has an incurable habit of looking at his surroundings and then trying to discover who built what, and why. As a senior in Harvard College half a dozen years ago, he studied the history of the Harvard Houses. He has written about his own Jones Hill neighborhood in Dorchester. His work in organizing the papers of Ralph Adams Cram and other architects and craftsmen in the Boston Public Library led first to the publication in 1974 of his Church Building in Boston, 1720-1970 and the next year to a great Cram exhibition at the library, for which he wrote Ralph Adams Cram, American Medievalist. A centennial history of All Saints' Church, Ashmont — Cram's early masterpiece in the region — also appeared in 1975. In a secular mood, Mr. Tucci prepared in 1977 a walking tour of Boston theaters, concert halls, and movie palaces for the City Conservation League. In all of these studies he spread so wide and deep a net as to bring up a rich haul of unfamiliar material, which he skillfully presents in this book.

Since the period described is one in which Boston was overflowing its boundaries, Mr. Tucci rightly considers the architecture of neighboring towns, whether or not they were formally annexed to the city. Once public transportation brought places within easy reach of downtown Boston, houses proliferated in the same way in Dorchester, which became part of the city in 1870, and in Cambridge and Brookline, which are independent municipalities. In Chapter 4, "Streetcar City, Garden Suburbs," he gives an enlightening account of this process, using Jones Hill in Dorchester, which he knows intimately, as a point of departure. He indicates that large houses on small lots there were deliberately planned that way from the beginning, and that their proximity to each other and to the sidewalk was not the result of subsequent intrusions. He suggests that this sprang from a memory of the first decade of the nineteenth century on Beacon Hill when Bulfinch was designing for Harrison Gray Otis and others freestanding houses that, due to shortage of land, were later incorporated in solid blocks.

He may well be right, for I have never been able to fathom why, around Brattle Street in Cambridge, on, let us say, Fayerweather Street, people built in the late nineteenth century large, often expensive, and sometimes well-designed free-standing houses on diminutive lots. To me there is more privacy in a Back Bay block, or in one in London, Paris, Rome, or most European cities. But the hankering to have a freestanding house, even if your land is so small that you can look into your neighbor's side windows, is not exclusively a Bostonian or an American folly. In Barcelona, where the Gothic city and the huge nineteenth-century ensanche that enfolds it consist of solid blocks of apartments and houses, there is at the head of the Paseo de Gracia a region of luxurious free-standing villas, built on as exiguous pocket-handkerchiefs of land as anything in the Boston suburbs.

Chapter 5 on apartment houses and Chapter 9 on theaters and movie palaces present useful ideas about ubiquitous structures that most Bostonians have simply thoughtlessly taken for granted. The pioneering Hotel Pelham of 1857 and its 1870 neighbor, the Boylston, at the comer of Tremont and Boylston streets, have long since vanished, as have the apartment houses in Copley Square. The first apartment house on Commonwealth Avenue, Ware and Van Brunt's Hotel Hamilton of 1869, was demolished in the last decade by developers who hankered to put a taller structure on the site. As they were foiled by legal action, the lot once occupied by the hotel at the northwest corner of Clarendon Street is still vacant, save as a children's playground. Two blocks up at Exeter Street, the Hotel Agassiz (191 Commonwealth Avenue) of 1872 is still considered a delightful place to live, although it has passed the century mark. Mr. Tucci follows the evolution of the apartment house through Boston and the suburbs, calling attention to significant examples that many of us have passed for years without thinking about.

His account of the theaters particularly intrigues me, for as a child I was taken to see Ben Hur in Edward Clarke Cabot's Boston Theatre (of the 1850s) in Washington Street. Then too I delighted in the "crystal waterfall staircase," electrically lighted, with which B. F. Keith had adorned his adjacent Bijou Theatre. When I was in Boston Latin School sixty years ago, my idea of a Saturday morning's diversion was to see a film in the Modem Theatre in Washington Street — then correctly named, for it was built in 1914 — before going on to look for books at Goodspeed's, Smith and McCance, De Wolfe-Fiske's, Lauriat's, and in Cornhill. As the theater district has fallen upon evil days, we tend to forget how many, and how splendid, playhouses were built in the period covered by this book. Unlike the Boston Opera House, most of them are still there, although often in a state of sorry dilapidation.

Interesting as these novelties are, the true point of Built in Boston is that it follows local architectural taste from Bulfinch through the Greek Revival, the ltalianate, the French Second Empire, and Victorian Gothic to H. H. Richardson; on to the Colonial Revival, the Classicism of Charles F. McKim, and the Gothic vision of Ralph Adams Cram, and makes these transitions seem plausible in relation to the pluralistic culture that emerged during the phenomenal nineteenth-century growth of Boston.

In regard to the eclecticism that prevailed from 1890 to the 1930s, Mr. Tucci observes that "well-traveled and well-educated architects, with well-stocked libraries of measured drawings and photographs of seemingly everything ever built and an endless supply of excellent immigrant craftsmen, coincided with clients equally well-traveled and well-educated and (until 1930) with more money than they often knew what to do with." The Boston Public Library owes much to the mutual understanding and shared enthusiasms of architect and client, for during its construction the president of the trustees was Samuel A. B. Abbott, who later became the first director of the American Academy in Rome. Abbott and McKim egged each other on, enjoyed the process, and obtained superior results. The architect Herbert Browne, who knew Italy intimately and loved to find there marble columns, busts, and bas-reliefs, had a similarly close relation with some of his clients. The design of the music room at Faulkner Farm in Brookline emerged from the combination of four colossal marble columns and a painted octagonal room that he found in Mantua, and a set of tapestries that his client, Mrs. Brandegee, already owned. While the columns determined the height of the room, its length was established by the size of the tapestries, and the Mantua room became a slightly elevated stage where musicians could perform.

Mr. Tucci obviously sympathizes with the belief of the eclectics "that the historical associations of a style were crucial to a building's functional expression, provided all the modem conveniences were worked into it." Mr. Tucci is young enough to be able to do so. The fear of being thought old-fashioned, ill-informed obscurantists led too many of my generation to ignore or deprecate such a masterpiece of traditional eclecticism as Lowell House at Harvard, which still pleases the eye while usefully serving the purpose for which it was designed nearly fifty years ago. Mr. Tucci is free from such prejudices. I greatly like his book. I wish Walter Kilham were still around to enjoy it.

Walter Muir Whitehill died on March 5, 1978, as this book was going to press. I first met him at the Club of Odd Volumes in 1972 when I was a senior in Harvard College, and I will always recall how he welcomed me to those distinguished precincts as if I had just written a brilliant first book. Later that year, when I did send my first book to him — timidly, for it was not brilliant — back from Mr. Whitehill came the first of many warmly encouraging letters. Though we were often associated publicly, it is for these more private kindnesses that I will chiefly remember him. Once I had to be in North Andover; nothing would do but that Mr. and Mrs. Whitehill should meet me at the bus stop, drive me to and from my appointment, give me a most handsome lunch, and deliver me back to the bus stop at the end of the day. Recently, Mr. Whitehill did me another kindness; as it turned out, the last: on Christmas Day of 1977 he called me at home to tell me how much he had enjoyed Built in Boston. He talked long and eloquently of Boston buildings and Boston friends, nicely relating everything to my manuscript — in part, no doubt, because he must have guessed that there was no one whose opinion of my work mattered more to me. It is for that reason, when I learned of his death, that I asked Dennis Crowley and Stuart Myers, for whom this book was written, if I might dedicate it instead to Mr. Whitehill's memory. I am grateful to them for encouraging me to do so.

Introduction

This book is the result of a course in the history of architecture in Boston that I was invited to give by Harvard University in 1977 at the Center for Continuing Education under the Faculty of Arts and Sciences. That course, in turn, derived from a series of public lectures that John Corcoran persuaded me to undertake in the spring of the same year at the Women's City Club of Boston, where I first felt the sense of outrage and helplessness any instructor must feel when he realizes that there is just no book at all to give to students about a subject worthy of a great many books. Thus when Robin Bledsoe of the New York Graphic Society asked me if I would care to revise my lectures for publication, I agreed at once.

Although I was born in the city of Boston, I did not really grow up in the city, which as a boy I saw only briefly when home from school. Summers too were spent elsewhere. But I was fortunate in having older friends who knew Boston well: Harrison Hale Schaff, David Landau, Francis Moloney, George Ursul, and Jim Hart. It was through them — particularly Dr. Landau, who bought and restored a Back Bay town house, and Professor Ursul, who undertook a similar restoration of a South End house — that with neither design nor fervor on my part I finally discovered Boston as a young man. For me, such was my taste and ultimately my vocation, this meant Boston's buildings. Nor was I surprised in 1976 when forty-six architects, critics, and historians throughout the country were asked by editors of The Journal of The American Institute of Architects to name "the proudest achievements of American architecture over the past 200 years" that only New York City gathered as many nominations (twenty-nine) as Greater Boston. The city of Boston alone, which is a much smaller part of its metropolis than are most other central cities in the United States, accumulated more nominations than all but two cities, New York and Chicago. Architecture in Boston, though this is the first full-length history of the subject, is obviously a large part of architecture in America.

There are any number of ways one might set about such a book. What I have done is to integrate my own research with that of other scholars into a general survey that is strongly rooted in Boston's overall cultural history and emphasizes the influence of six great architects — Bulfinch, Richardson, McKim, Cram, Sullivan, and Gropius — though Bulfinch and Gropius are, respectively, prologue and epilogue. Two themes are interwoven throughout: I have sketched the architectural contours of Boston, what could be called the architectural topography, as it has expanded and differentiated itself into recognizable "built environments," while at the same time following the thread of style and fashion through its many shifts and vagaries. The treatment is not exhaustive; this is not the mammoth study that the history of Boston's architecture will surely yield one day. What I have tried to do is to show what David McCord has called "the swing of the pendulum rather than the bowels of the clockworks; to let a handful of leaves in their venation suggest the tree itself; to bid the story of but three or four individuals acknowledge the story of literally hundreds." I have, on the other hand, sought to build this book as I do my course from fairly simple foundations to what is, finally, a more complex profile. The book thus develops as it progresses so as to introduce the reader through fairly detailed discussions of a few pivotal architects and buildings to increasingly complex factors in both the philosophy of architecture and in design itself — ranging from the Gothic church to the apartment house and the movie palace; three building types in the development of which in this country Boston has played a conspicuous and too long overlooked part.

About half the book is drawn from my own research. The section on the Harvard Houses derives largely from an unpublished history of them I coauthored with David Mcl. Parsons as the result of a grant for that purpose from the Harvard Faculty of Arts and Sciences in my senior year at Harvard College in 1972, though the conclusions here are entirely my own. The streetcar suburbs chapter proceeds from much subsequent research since my book of 1974 on that subject, The Second Settlement, but it still owes a great deal to the generous funding of my work by St. Margaret's Hospital for Women. Any kind of history of a great city must depend to some extent on building blocks of neighborhood history (Bunting's architectural history of the Back Bay, for instance) and if a dozen or so other Boston institutions would do for their neighborhoods what St. Margaret's did for Jones Hill in Dorchester, we should know much more about Boston. The Cram chapter is rooted in my study of Cram and his work, an effort made possible by his successor firm, Hoyle, Doran and Berry, and by the Boston Public Library and the First American Bank for Savings. The chapter, "French Flats and Three-Deckers," is the result of entirely unpublished research I have undertaken on my own, as is also the section on Louis Sullivan and Boston, an interest stimulated by my trip to Chicago in 1976 to lecture at the Art Institute for the local chapter of the Society of Architectural Historians. Through "Bunny" Selig's generosity, I was allowed to see Sullivan's superb Stock Exchange Trading Floor being restored and rebuilt into the Art Institute. I had just previously attended the unveiling of the Sullivan plaque in Boston, and a train of thought was stimulated, the results of which are published here. Finally, the chapter on the Boston rialto derives from my monograph of that title, published in 1977 by the City Conservation League.

Throughout, I have indicated my principal sources in the text. Complete checklists of source material consulted for selected Boston building areas, building types, and architects are also included. Otherwise, each of the chapters documents itself. (A list of abbreviations used in the captions and bibliography is given on page 235.) When the designer or date of a specific building is not general knowledge, the address of the building has always been given, and this will always yield the relevant sources at either the building department of the city or town in which the building is located or in the Boston architecture card index maintained at the Fine Arts Department of the Boston Public Library. That card index, itself the source or verification for many attributions here, includes also the results of data I have unearthed elsewhere. If I have thus been able to avoid what Sir John Betjeman has called a “rash of foot and note disease," I have consequently had to ignore Henry Adams's admonition: "to overload the memory with dates is the vice of every schoolmaster and the passion of every second rate scholar." The date of every building touched on is given in the text or in the captions. Otherwise to traverse so long a period would ensure that many would lose their way.

Dates of buildings, of course, are always problematical: Symphony Hall, for example, and the first Museum of Fine Arts were designed many years before they were built. Even in the case of buildings where design and construction were continuous, one can choose the date of the drawings, or of their publication, or of the groundbreaking, or of the dedication. And sometimes, in the case of quite large buildings, different parts were designed, begun, and opened in different years and often are the work of different architects. In general, I have dealt with these problems by settling on the date the building was sufficiently completed to be opened for use. Otherwise I have usually indicated that the date given is that of its design or completion or whatever. In the case of (mostly) major works, the inclusive dates given are the date the plans were begun and the date the building opened. In the case of minor works, dates derive largely from Building Department records; otherwise I have used what might be called the most authoritative sources for whatever area or building type or oeuvre is involved. For example, for Bulfinch, Kirker's The Architecture of Charles Bulfinch; for McKim, Leland Roth's appendices to the new edition of the monograph on the firm's work; for Back Bay houses, Bainbridge Bunting's Houses of Boston's Back Bay; and in many instances, Walter Muir Whitehill's always reliable works.

I have relied here upon the more or less standard words and terms used by architectural historians, though even when they do not fall into the category of jargon, these are almost never luminous. For years scholars sought and failed to find something better for even so basic a word as Gothic — and most of the terms now universally used are invariably misleading or confusing. Nor is there any way out of this — historians as in so many things are trapped by the history they study: by no means are all shingled houses "Shingle Style"; the streetcar suburbs are to my mind full of town houses; the Queen Anne style has very little to do with Queen Anne; and one might fill a sizable book and also waste a great deal of time ruminating about the innumerable refractions of words like "eclectic," "modern," "picturesque," "romantic," and so on. As every attempt I am aware of to reform this vocabulary has only added to the confusion, I have resisted the temptation to attempt my own reform. Yet throughout the book I have used two words — "Medieval" and "Classical" — in a way that I hope will be helpful. The idea derives from Harmon Goldstone and Martha Dalrymple's History Preserved: A Guide to New York City Landmarks and Historic Districts (New York, 1974), where all these terms were organized into two overall categories: the Classical tradition and the Romantic tradition. For a variety of reasons I would dispute the value of one term and the authors' definitions of both. But the idea of thus organizing stylistic terms in this way seems to me a good one, for throughout the period covered by this book, two great traditions in Western architecture have animated Boston: the Classical tradition, work characterized by orders of columns, capitals, and entablatures that show a descent from Greece and Rome, either directly or through the Renaissance, and which are characteristically symmetrical in massing and detail; and the Medieval tradition, work that shows an affinity for the Middle Ages and is characteristically organic, asymmetrical, broken, or rambling in mass. Both traditions have been continually submerging and reappearing throughout American architectural history, and both have often shaded into each other. A building may be Classical in detail and asymmetrical or Medieval in overall massing. In that case one can only call it "picturesque," a word architectural historians use too much, but necessarily; some would capitalize it and virtually erect it into a style of its own.

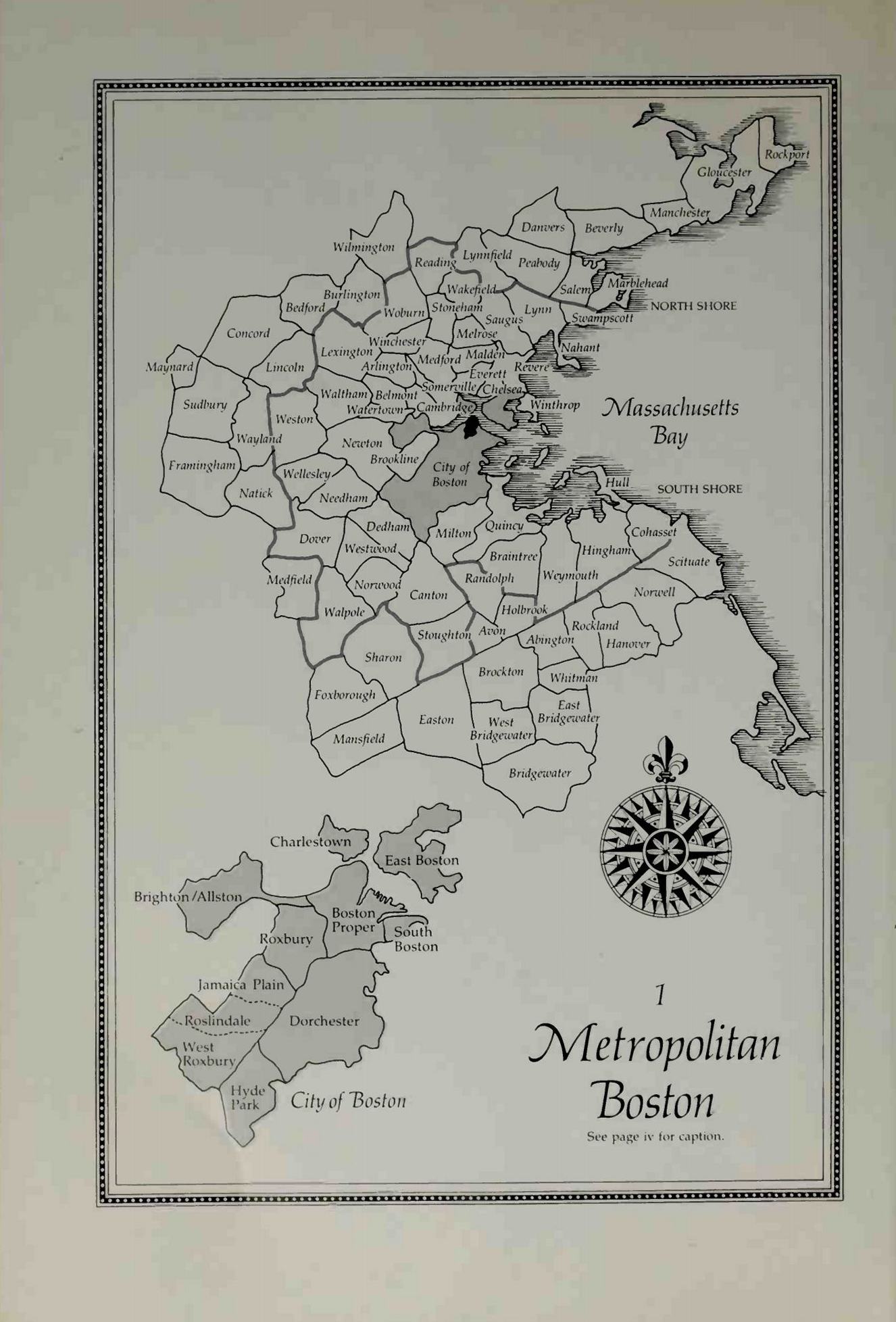

Another word, the use of which may at first confuse, is Boston, for the definition in these pages parallels, as it should, that of each historical period dealt with — in the sense that Boston expands in each chapter as it expanded historically, from town and city to metropolis (see Maps 1 and 2). Thus in 1800 Newton is not treated as part of Boston, for it was then isolated and quite unrelated to the early nineteenth-century town of Boston. By the 1850s, however, it was an emerging suburb whose architecture is briefly considered because it was related to the city's, and after the 1870s it was culturally, socially, and architecturally a part of Boston (so much so that Boston College is in Newton, not in the city of Boston) and is treated as such. Except for occasional forays to discuss Bostonians' country houses and for one or two types of buildings no longer extant in Boston in a given period, it is in this manner that Boston's meaning expands in this book from one period to the next. It is also for this reason that this book ignores such notable seventeenth-century suburban Boston architecture as the Old Ship Church in Hingham and the Saugus Iron Works. Neither place could be called a suburb until the late nineteenth century. The bibliography, however, includes sources for all the "pre-suburban" architecture of every city and town now in the Boston Metropolitan District. Some areas naturally possess much more significant architecture than do others. A corollary problem is that places like the Back Bay, Dorchester, and Cambridge have been extensively studied and documented; other places like Everett, Newton, East Boston, or Hyde Park have scarcely been noticed.

Finally, I hope that Built in Boston reflects generally the great sense of pride I take in the accomplishments of a number of my colleagues in the Boston/New England Chapter of the Society of Architectural Historians — particularly Robert Bell Rettig, Margaret Henderson Hoyd, Wheaton Holden, Bainbridge Bunting, Theresa Cederholm, and Cynthia Zaitzevsky. Each has in one way or another labored very hard to document Boston's architectural history. Others, like Ada Louise Huxtable of The New York Times, Leslie Larson, the founder of the City Conservation League, Gerald Bernstein of Brandeis, Eduard Sekler of Harvard, and A. McVoy McIntyre, of the Beacon Hill Civic Association, are due perhaps as much credit for bringing the subject so forcefully to the attention of students and the public. Indeed, I sometimes think that these dedicated men and women deserve better of Boston, which is too important a place to be left entirely in the hands of bureaucrats and city planners.

D.S.T.

Boston

March 1978

About the author:

Since his graduation from Harvard College in 1972, Douglass Shand Tucci has written and lectured widely on Boston architecture. His best-known book, Church Building in Boston, was described by the AlA Journal as "an important contribution to the history of American architecture." In 1974 he prepared for the Boston Public Library the first retrospective exhibition of the work of Ralph Adams Cram, an exhibit Ada Louise Huxtable in The New York Times called "impressive and illuminating." Since 1977 Mr. Tucci, who lives in Boston, has taught Boston architectural history at Harvard.

Contents

FOREWORD BY WALTER MUIR WHITEHILL viii

INTRODUCTION xiii

1 BEFORE AND AFTER BULFINCH 3

2 THE GREAT TRADITIONS 19

3 H. H. RICHARDSON'S BOSTON 46

4 STREETCAR CITY, GARDEN SUBURBS 73

5 FRENCH FLATS AND THREE-DECKERS 101

6 CHARLES MCKIM AND THE CLASSICAL REVIVAL 131

7 RALPH ADAMS CRAM AND BOSTON GOTHIC 155

8 THE SHADOW OF LOUIS SULLIVAN 182

9 THE BOSTON RIALTO 206

10 TOWARD GROPIUS 221

BIBLIOGRAPHY 233

INDEX 256

PICTURE CREDITS 268

MAP 1, Metropolitan Boston, is the frontispiece.

MAP 2, Boston Proper & Environs, is on page xiv.

Sample pages

Download link (pdf, yandexdisk; 46,9 MB)

Все авторские права на данный материал сохраняются за правообладателем. Электронная версия публикуется исключительно для использования в информационных, научных, учебных или культурных целях. Любое коммерческое использование запрещено. В случае возникновения вопросов в сфере авторских прав пишите по адресу 42@tehne.com.

1 апреля 2019, 18:51

0 комментариев

|

Партнёры

|

Комментарии

Добавить комментарий