|

|

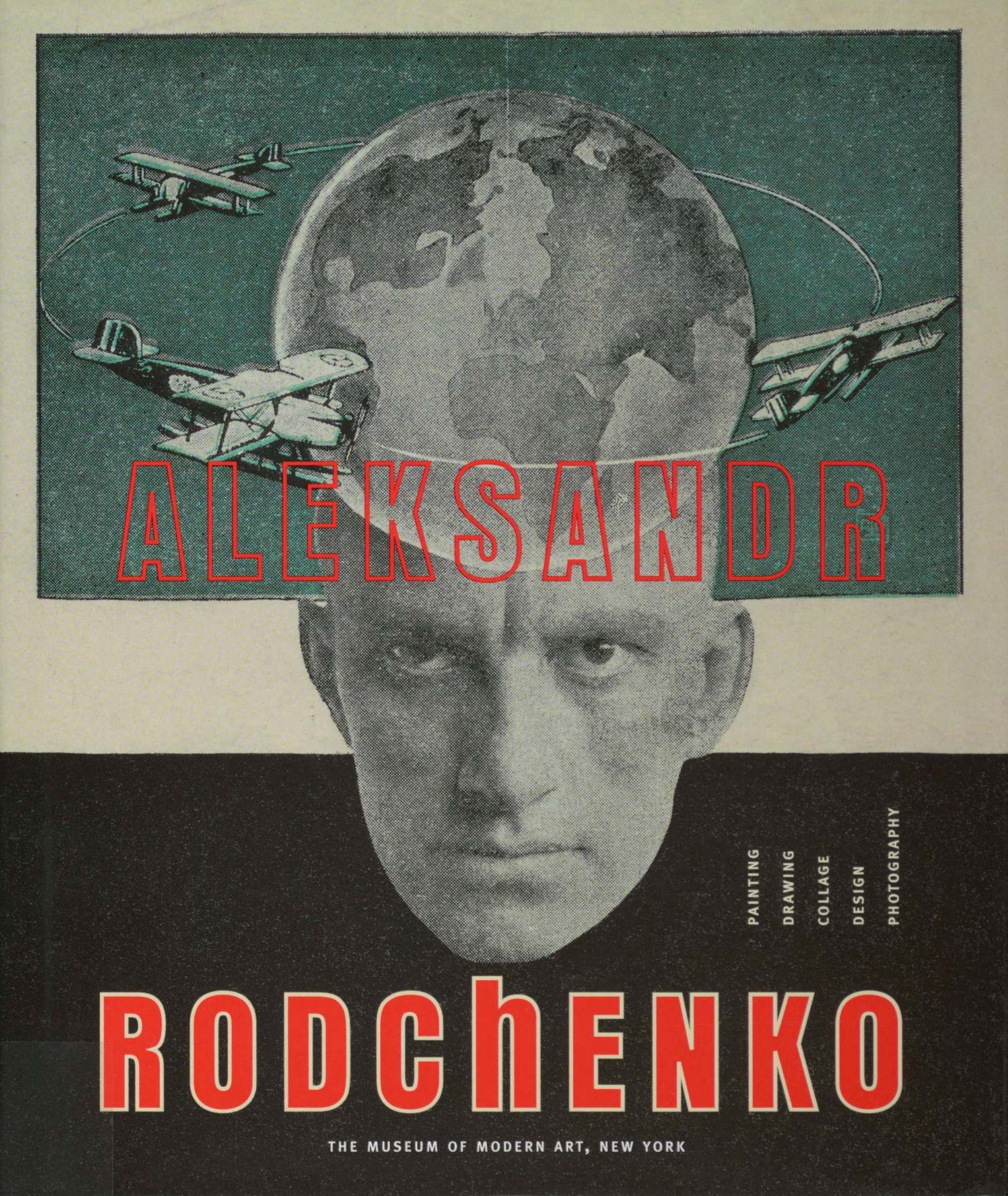

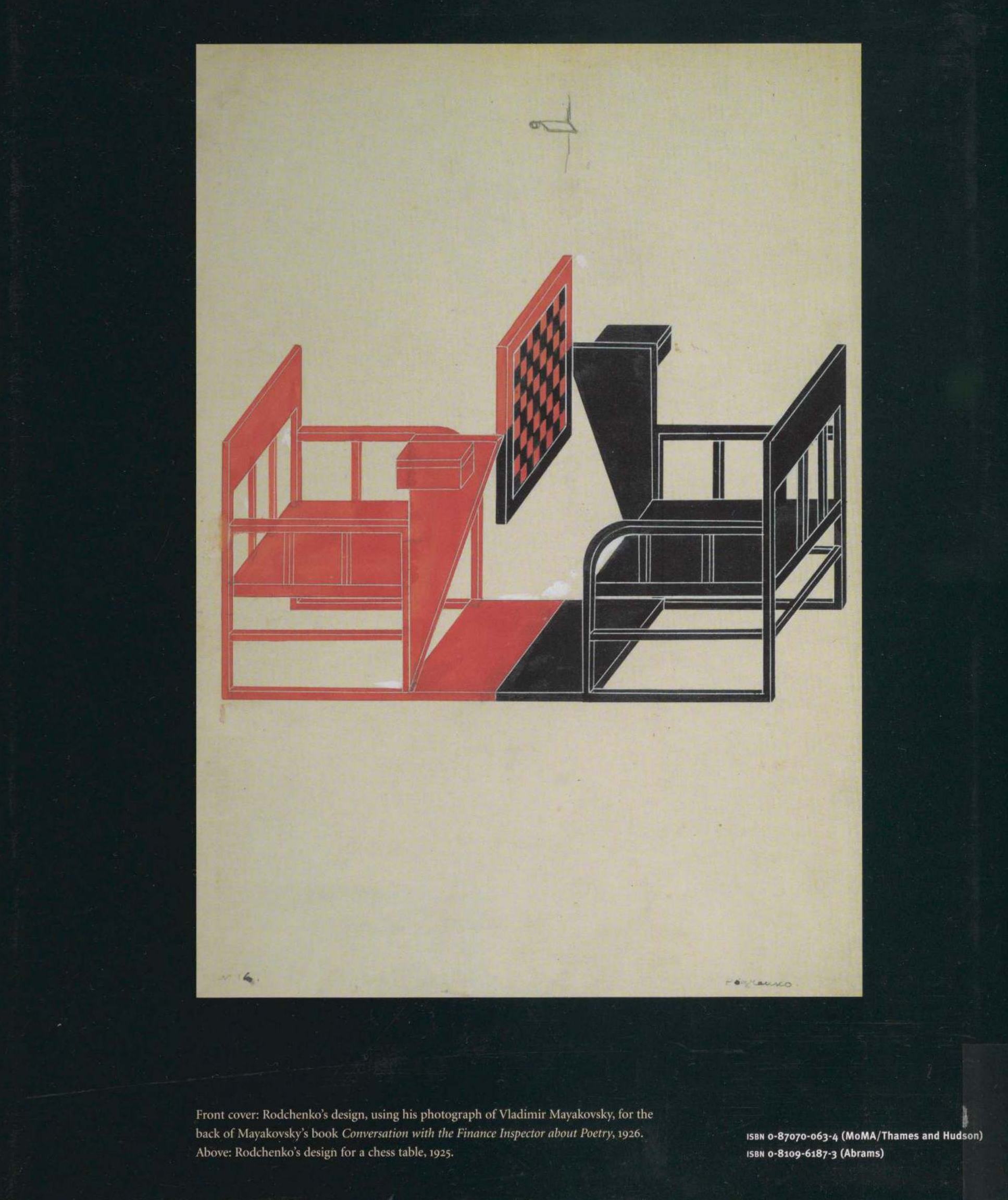

Aleksandr Rodchenko / Magdalena Dabrowski, Leah Dickerman, Peter Galassi, Aleksandr Lavrentev, Varvara Rodchenko. — New York, 1998  Aleksandr Rodchenko / Magdalena Dabrowski, Leah Dickerman, Peter Galassi, Aleksandr Lavrentev, Varvara Rodchenko. — New York : The Museum of Modern Art, 1998. — 336 p., ill. — ISBN 0870700634, 0870700642, 0810961873

In the aftermath of the Russian Revolution of 1917, a group of artists who came to call themselves Constructivists set out to create a new art in the spirit of the new society to come. Aleksandr Rodchenko (1891–1956), the most important and versatile member of the group, made outstanding and original works in virtually every field of the visual arts. In the first part of his career, Rodchenko produced innovative abstract painting, sculpture, prints, and drawings. In 1921, however, he made a bold break, committing himself to applied art in the service of revolutionary ideals, and moving on to lasting achievements in photocollage, photography, and design of all kinds: books, posters, magazines, advertising, furniture.

This book is published to accompany the first major American retrospective of Rodchenko’s work, at The Museum of Modern Art, New York, in the summer of 1998. The essays in Aleksandr Rodchenko explore both phases of his career, drawing out the formal ideas that he developed as well as the social and artistic context in which he moved. The book’s plate section, reproducing over 300 works carefully selected from collections in Russia and throughout the West, for the first time presents a full and coherent overview of his diverse achievement. An illustrated chronology outlines the story of the artist’s life.

Magdalena Dabrowski is Senior Curator in the Department of Drawings, The Museum of Modern Art.

Leah Dickerman is Assistant Professor of Art History, Department of Art, Stanford University.

Peter Galassi is Chief Curator in the Department of Photography, The Museum of Modern Art.

Aleksandr Lavrent’ev and Varvara Rodchenko, Rodchenko’s grandson and daughter, together maintain the A. Rodchenko and V. Stepanova Archive, Moscow, and have published extensively on the artist’s work.

CONTENTS

6 Foreword

7 Acknowledgments

10 Introduction

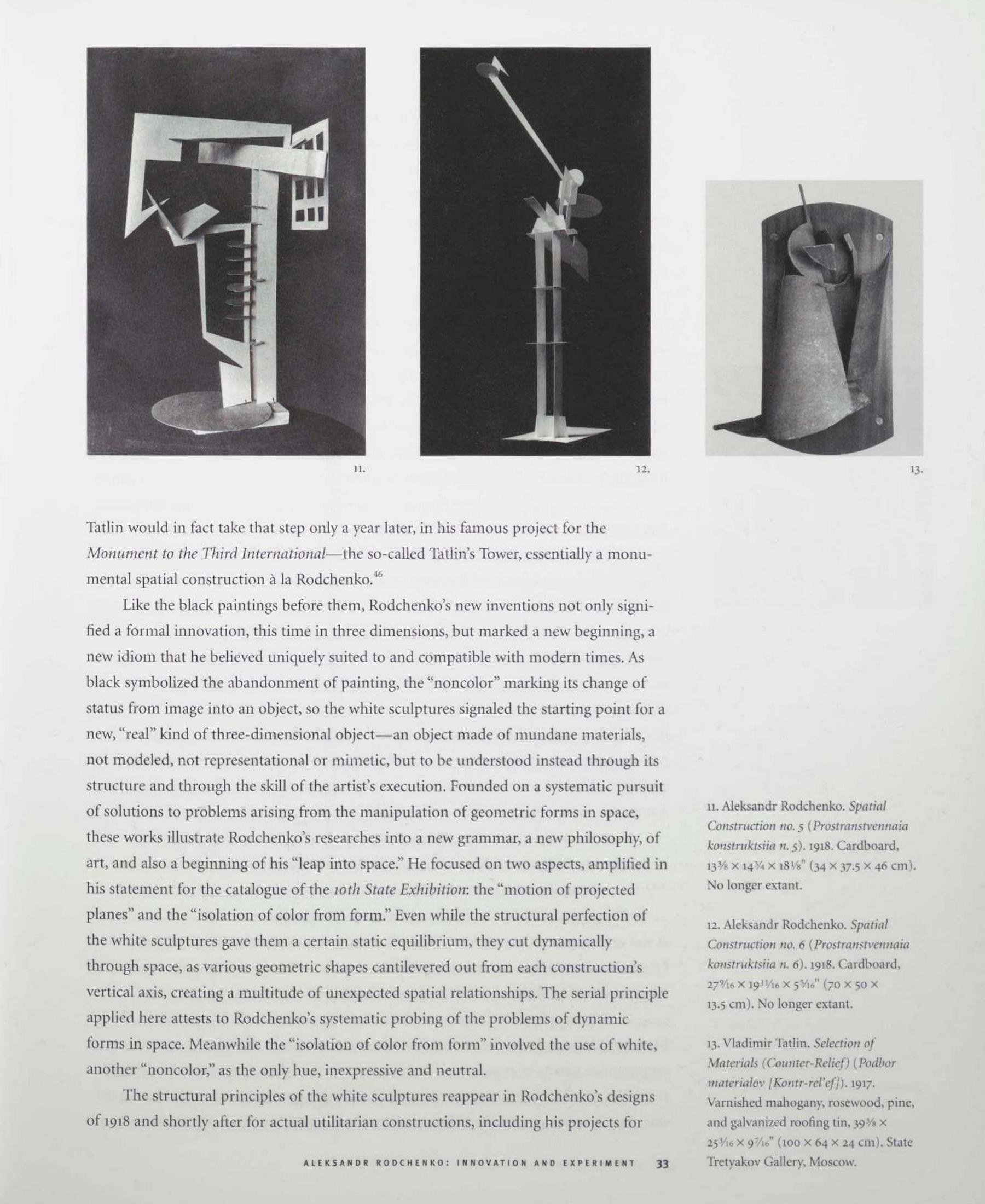

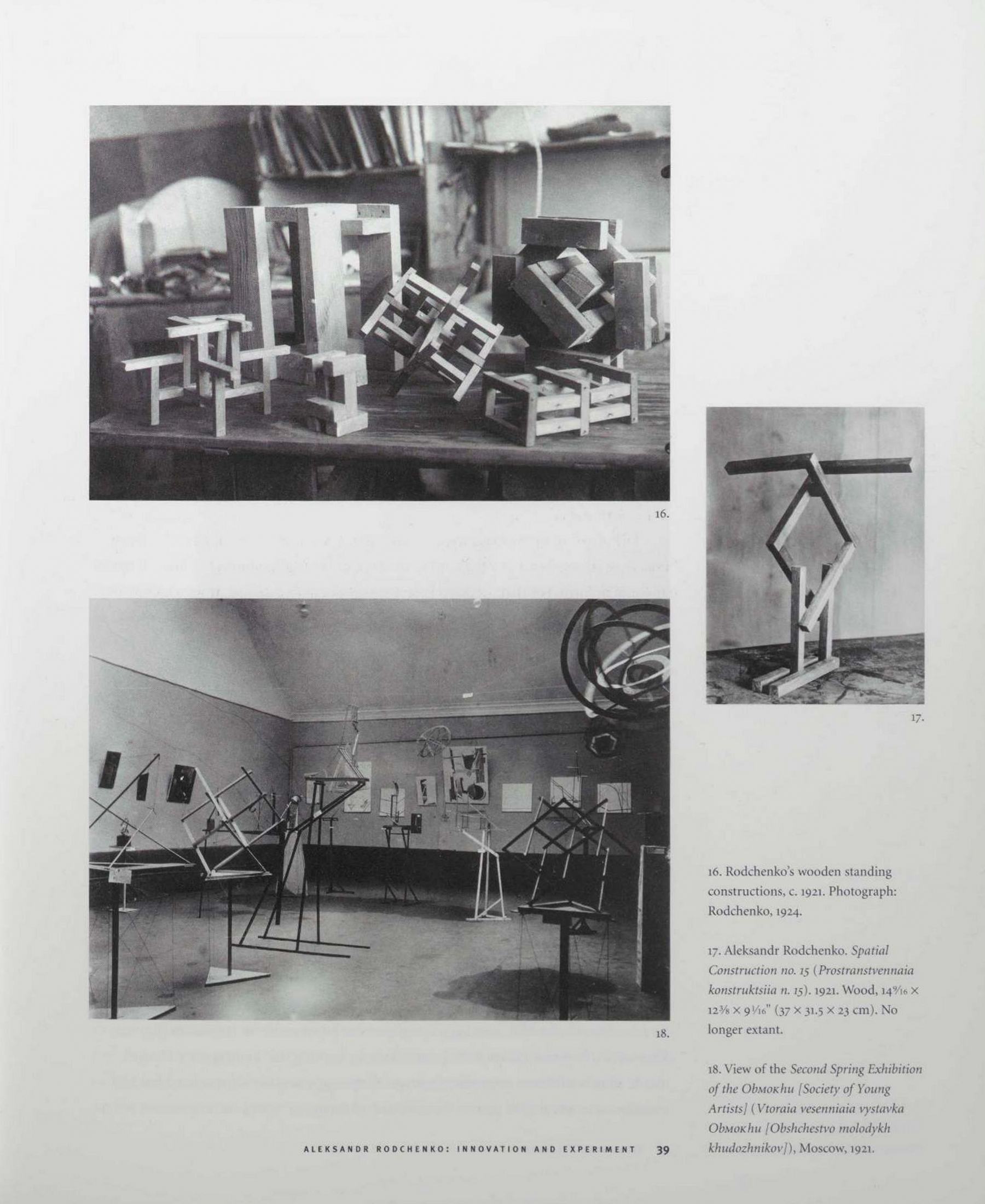

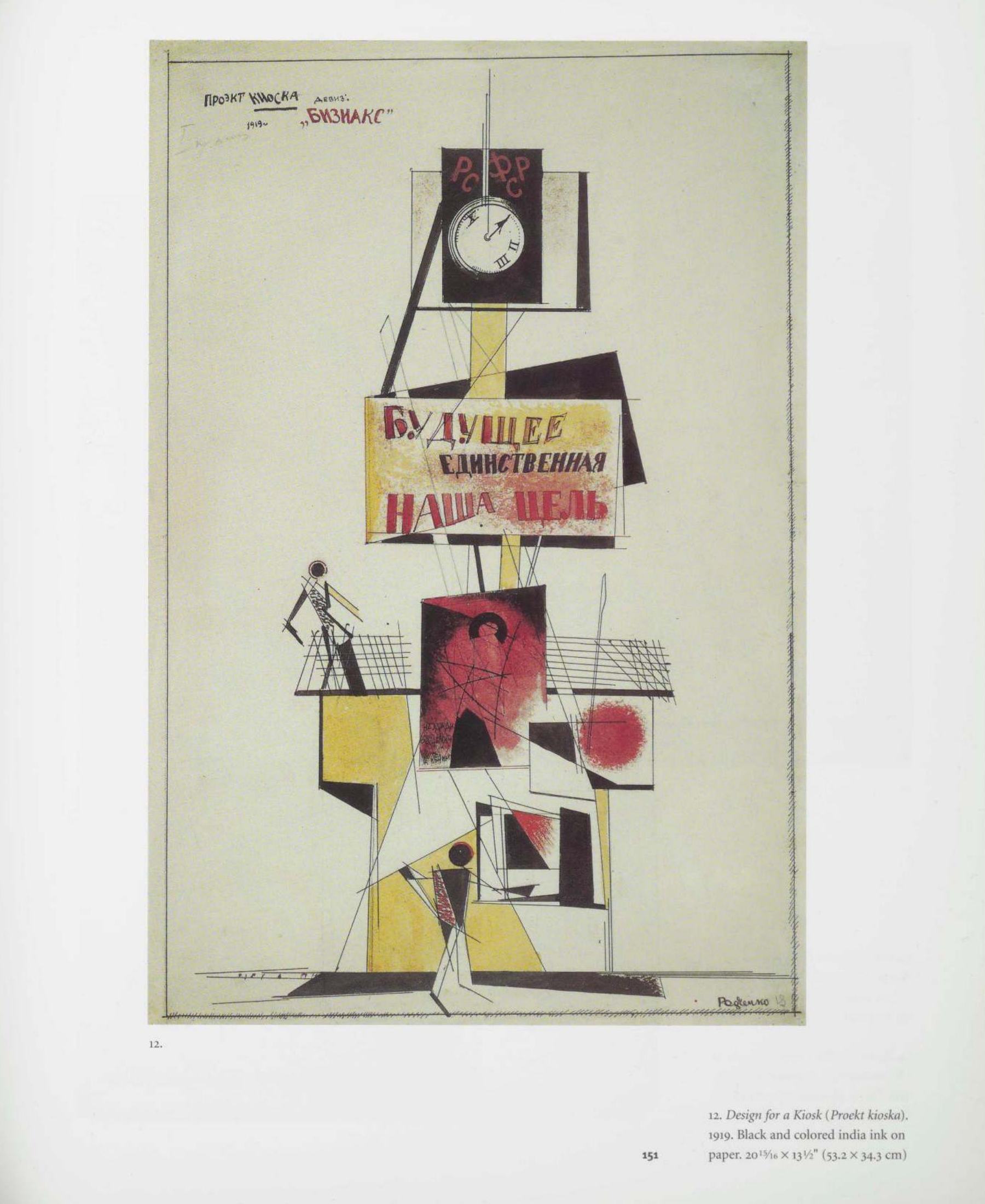

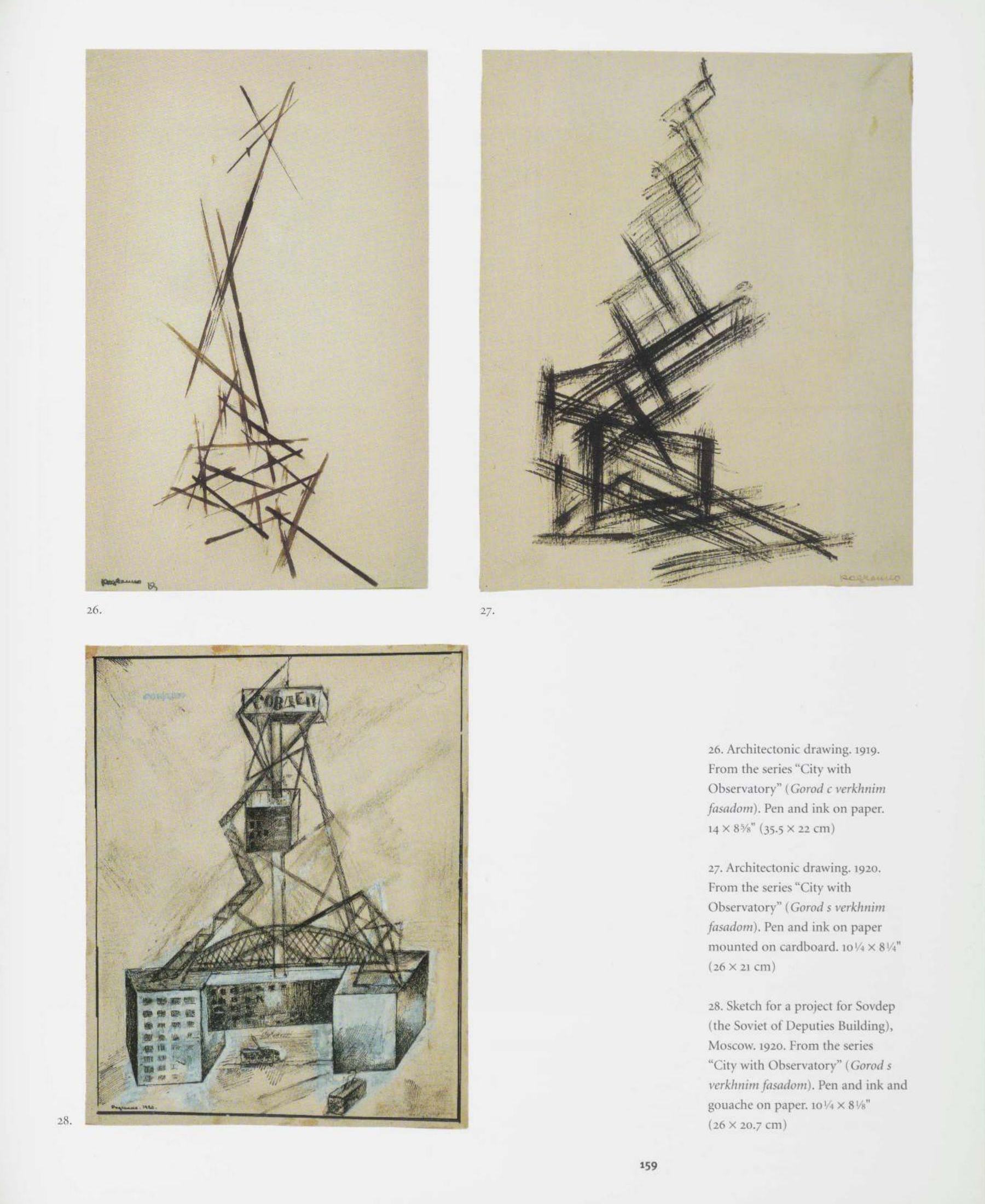

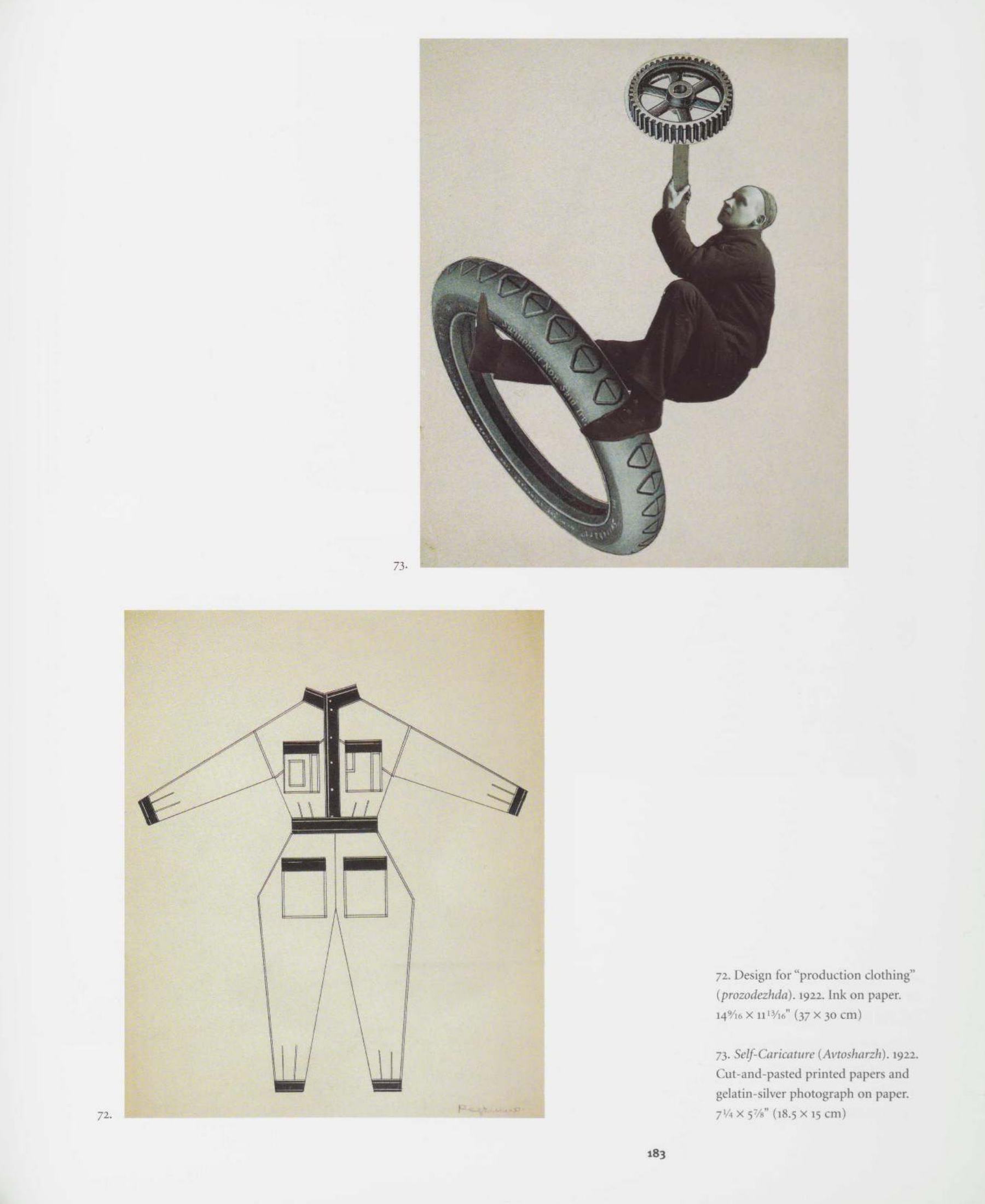

18 ALEKSANDR RODCHENKO: INNOVATION AND EXPERIMENT

Magdalena Dabrowski

50 ON PRIORITIES AND PATENTS

Aleksandr Lavrent'ev

62 THE PROPAGANDIZING OF THINGS

Leah Dickerman

100 RODCHENKO AND PHOTOGRAPHY’S REVOLUTION

Peter Galassi

138 DAYS IN THE LIFE...

Varvara Rodchenko

144 PLATES 1915–1939

300 Chronology

313 Catalogue of the Exhibition

327 Bibliography

332 Glossary

333 Index

335 Lenders to the Exhibition

336 Trustees of The Museum of Modern Art

Foreword

In the winter of 1927–28, nearly two years before he became the founding director of The Museum of Modern Art, Alfred H. Barr, Jr., traveled to Russia to study the new art that was flourishing there. One evening in Moscow he visited Aleksandr Rodchenko, whose relationship with the Museum thus began even before the Museum existed.

While in Moscow Barr also visited the Museum of Painterly Culture, which Rodchenko had directed in 1919–20, and whose systematic displays of advanced art anticipated a key aspect of the program Barr would establish in New York. Another important aspect of Barr’s program was the wide range of mediums collected by The Museum of Modern Art—not only painting, sculpture, drawing, and printmaking, but also design, photography, and film. Barr recognized that the interrelationships among these diverse mediums are central to the vitality of modern art, and none of the great modernists was more versatile than Rodchenko, who made outstanding work in virtually every medium collected by the Museum. For all of these reasons it is gratifying and highly appropriate that this exhibition—the first major Rodchenko retrospective in the United States—should be organized by The Museum of Modern Art.

In their Acknowledgments, the curators express the Museum’s gratitude to the many generous lenders to the exhibition. I would like to add a special note of thanks to our great friends and frequent partners in Russia: Irina Antonova, Director, Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow; Valentin Alexeevich Rodionov, Director, State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow; and Evgenia Nikolaevna Petrova, Deputy Director, State Russian Museum, Saint Petersburg. Our greatest debt is to the artist’s daughter, Varvara Rodchenko, and her son, Aleksandr Lavrent’ev, who have not only lent generously but have tirelessly assisted the Museum in realizing the exhibition and this book.

I am also pleased to acknowledge generous support for the exhibition and this book from The International Council of The Museum of Modern Art and the William Randolph Hearst Endowment Fund. The Hearst endowment, for photography exhibitions, was established in 1997 with a generous grant from the William Randolph Hearst Foundation. I am thankful as well for the welcome support we have received from the Trust for Mutual Understanding, The New York Times Company Foundation, and the Howard Gilman Foundation.

The goal of this ambitious exhibition is to present a coherent view of Rodchenko’s achievement in all of its prodigious variety. This has required the talent and expertise of three curators: the Museum’s own Magdalena Dabrowski, Senior Curator, Department of Drawings, and Peter Galassi, Chief Curator, Department of Photography; and guest curator Leah Dickerman, Assistant Professor of Art History, Stanford University. Each has brought a profound understanding of Rodchenko, a keen sensibility, and a remarkable intelligence to this project. As a truly collaborative effort, their work together exemplifies a great strength of this museum.

—Glenn D. Lowry, Director, The Museum of Modern Art

INTRODUCTION

This book accompanies the first major exhibition in the United States of the work of Aleksandr Rodchenko, a founder and central protagonist of Constructivism—the vigorous artistic movement that arose in Russia after the Revolution of 1917. Like other leading modernists in Russia and the West, Rodchenko was a keen inventor of forms. In pursuit of Constructivist goals he also became a versatile innovator in a much broader sense; after producing bold work in painting and sculpture, he still more boldly abandoned these traditional mediums and reconceived his art in the service of the radically progressive, technologically advanced society envisioned after the Revolution. This ideal of social agency eventually involved him in virtually every branch of the visual arts, including projects of design and photography addressed to a mass audience. As a result, Rodchenko’s work is perhaps the most diverse body of work created by any major twentieth-century artist, and the least susceptible to a narrow aesthetic interpretation. The primary goal of this exhibition and book is to present a coherent overview of his achievement in all of its diversity.

Rodchenko was born on November 23, 1891, just thirty years after Tsar Aleksandr II emancipated the serfs of Russia. His father, Mikhail Mikhailovich Rodchenko, the son of a serf, had left his native province of Smolensk and made his way as a laborer to the capital, Saint Petersburg, learning to read and write along the route. After the turn of the century, the family moved to distant Kazan, where Rodchenko earned a certificate of elementary education and eventually entered the local art school. Thus Rodchenko’s own family story seems to suggest that genuine social progress was underway in Russia. If so, it was too little too late.

The autocratic power of the Romanov dynasty had long been enforced through an alternating pattern of grudging reform and brutal repression, which intensified in the nineteenth century in the face of political turmoil and social transformations throughout Western Europe. In this climate there emerged a vibrant intelligentsia (a Russian word coined in this period) of dissidents inspired by Western ideals of freedom and social justice, who established a tradition of uncompromising moral commitment to radical political change. Although Russia remained largely an agricultural country populated by grievously burdened peasants, rapid industrialization at the end of the nineteenth century brought rising social tensions and helped to foster the growth of a fiercely dedicated political underground. Among the leading elements was the Russian Social Democratic Labor Party (Russkaia sotsial-demokraticheskaia rabochaia partiia), founded in 1898 and committed to the revolutionary program of Karl Marx. In 1903, the party split into Bolshevik (“majority”) and Menshevik (“minority”) factions. The former, led by Vladimir Il’ich Lenin, advocated immediate revolution and class war.

The first mass uprising against the tsarist regime occurred in 1905, and, although it failed, it strengthened the resolve of the radical parties. The onset of World War I in 1914 presented a renewed challenge to the weak Tsar Nicholas II, as military defeats abroad and food shortages at home created widespread discontent, provoking strikes in Petrograd (as Saint Petersburg had been rechristened, to rid the name of its Germanic connotation) and Moscow. Violent disturbances in late February 1917 forced Nicholas to abdicate, ending three centuries of Romanov rule. A democratic, bourgeois Provisional Government was formed, but proved no match for the single-minded Bolsheviks, who seized power in Petrograd on October 25.1 They immediately set out to dismantle the embryonic apparatus of democracy that had grown up after February and to dominate or eliminate rivals, including the soviets, or councils, of workers in whose name they had assumed power. Although the coup itself was relatively bloodless, it took three years of very bloody civil war for the Bolsheviks to secure control over the vast country.

____________

1 In March 1918 the seat of government was moved to Moscow, which was considered safer because more distant from the Western border.

Marx had taught that all dimensions of social life were expressions of class interest, and Lenin believed that society therefore had to be thoroughly remade in the interests of the victorious proletariat. The sole agent of this "dictatorship of the proletariat" was to be the Communist Party, as the Bolsheviks renamed their organization in March 1918. This was the first of the twentieth century’s totalitarian regimes, and for many in Russia and abroad the idealism of its stated social goals at first masked its terrible novelty.

Magdalena Dabrowski’s essay on pages 18–49, which traces Rodchenko’s career through 1921, includes an account of his youth and artistic education. (See also the Chronology on pages 300–312.) The key development was his move in late 1915 or early 1916 from provincial Kazan to Moscow, where he instantly brought his art up-to-date with the current experiments of the avant-garde. There he rejoined the artist Varvara Stepanova, whom he had met in Kazan and who became his lifelong companion and frequent collaborator.

Beginning in the last decade of the nineteenth century and with increasing vigor in the decade before the Revolution, advanced Russian artists had pursued an unprecedented exchange with their counterparts in Europe. Russian painters, notably Vasily Kandinsky, played significant roles in developments abroad, while connoisseurs such as Ivan Morosov and Sergei Shchukin in Moscow were forming outstanding collections of advanced European painting, including superb examples of work by Georges Braque, Henri Matisse, and Pablo Picasso. Most important, Russian artists at home responded with enthusiasm to innovations in the West, often inflecting them with lessons drawn from native traditions such as icon painting and folk art, The key innovators were Kasimir Malevich and Vladimir Tatlin, each of whom by 1915 had elaborated the vocabulary of Cubism into a distinctive style of abstract art. Among the equally experimental poets was the flamboyant Vladimir Mayakovsky, later to become Rodchenko’s dose friend and collaborator.

The outbreak of World War I cut short the exchange, occasioning the return of the expatriates and helping to cultivate the specifically Russian dimension of the new art. Over the next few years Petrograd and Moscow enjoyed a period of thrilling and competitive creative ferment, marked by a series of landmark exhibitions. This was the heady artistic environment that Rodchenko entered when he arrived in Moscow, and he soon made his mark by presenting a group of austere drawings at the Store (Magazin) exhibition organized by Tatlin in March 1916. Shortly thereafter, however, he began military service as operations manager of a hospital train, and made very little new work until after his discharge in December 1917.

After the October Revolution, the Bolsheviks moved swiftly to suppress dissent—in 1918, for example, they liquidated the independent press, closing more than 150 daily newspapers in Moscow alone. Many members of the liberal intelligentsia soon emigrated, creating a relative vacuum of authority in academic and artistic fields. At least since the tailed revolution of 1905, an experimental attitude in art had been associated with progressive politics in Russia, and in artists’ circles “leftist” was a common shorthand for “avant-garde.” Indeed the avant-garde was the only artistic group to side unambiguously with the Bolsheviks, who in the precarious aftermath of the October Revolution welcomed any support. Thus it was that a tiny, gifted, obstreperous group, whose highly sophisticated art was unknown or incomprehensible to the vast majority of the Russian people, identified its own artistic ideals as the vanguard expression of the unfolding Communist society—and in the process created a unique and lasting body of art and theory.

At first the avant-garde enjoyed considerable institutional authority. Among the agencies of the new state bureaucracy (whose alphabet soup of abbreviations surpasses even the one spawned slightly later in America by the bureaucracy of the New Deal) was the Narodnyi komissariat prosveshcheniia, or Narkompros—the Peoples Commissariat of Enlightenment. Headed by the cosmopolitan Anatoly Lunacharsky, Narkompros administered all branches of education and culture and, by policy, encouraged artists of all tendencies. Alone among Bolsheviks in high places, Lunacharsky had a temperamental weakness for the leftists, whose work he studied and appreciated. They soon occupied prominent positions in Izo (Otdel izobrazitel’nykh iskusstv, the Section of Visual Arts of Narkompros). Tatlin's Monument to the Third International (Pamiatnik III Internationala) of 1919–20—a grand, highly imaginative, and wholly impractical design for a government building some 1,300 feet tall—arose from Lenin’s Plan for Monumental Propaganda, which Tatlin administered as the head of the Moscow branch of Izo in 1918–19.

Rodchenko’s rise to prominence in the years immediately following the Revolution was rapid and comprehensive. From 1918 onward he held several positions within Izo, notably as head of the Museum Bureau (Muzeinoe biuro) and its Moscow centerpiece, the Museum of Painterly Culture (Muzei zhivopisnoi kul’tury), both founded in 1919. In late 1920 he was appointed to an important teaching post at Vkhutemas (Vysshie gosudarstvennye khudozhestvenno-tekhnischeskie masterskie—the Higher State Artistic-Technical Workshops), the principal state art school, across the courtyard from the apartment building into which Rodchenko and Stepanova moved in 1922.

In a period when few if any Western museums took note of recent avant-garde art, the Museum Bureau, charged with establishing a network of provincial museums of contemporary art, was a farsighted institution. And under Rodchenko the Museum of Painterly Culture was perhaps the first not only to assemble outstanding examples of advanced art but to chart its formal evolution systematically—an aim that apparently made a lasting impression on Alfred H. Barr, Jr., when he visited the museum in 1928, the year before he became the founding director of The Museum of Modern Art in New York. The systematic character of the museum’s scheme reflected Rodchenko’s quasiscientific conception of artistic progress, which is the subject of the essay by Aleksandr Lavrent’ev on pages 50—61.

As the present exhibition demonstrates (despite the absence of a number of key works of sculpture long known only through photographs), the years from 1918 to 1921 were a period of intense creativity in Rodchenko’s art. Although fueled by competition with other artists including Malevich and Tatlin, this achievement was deeply rooted in Rodchenko’s conviction that the creation of a new, Communist art must be a collective enterprise. He derived much of the impetus for his own innovations from his vigorous participation in group projects, meetings, and associations. The most important of these was Inkhuk (Institut khudozhestvennoi kul’tury—the Institute of Artistic Culture), founded under the auspices of Izo in March 1920.

Inkhuk may be unique in the history of state-sponsored institutions, for its sole mission was to establish objective, universal principles of art, Rodchenko played a decisive administrative role at the institute, and was outspoken in articulating key positions in its heated theoretical debates. In February 1921 he helped to lead the group that drove Kandinsky from his position as head of one of the institute’s committees, and the following month, with Stepanova and others, he formed the First Working Group of Constructivists (Pervaia rabochaia gruppa konstruktivistov).

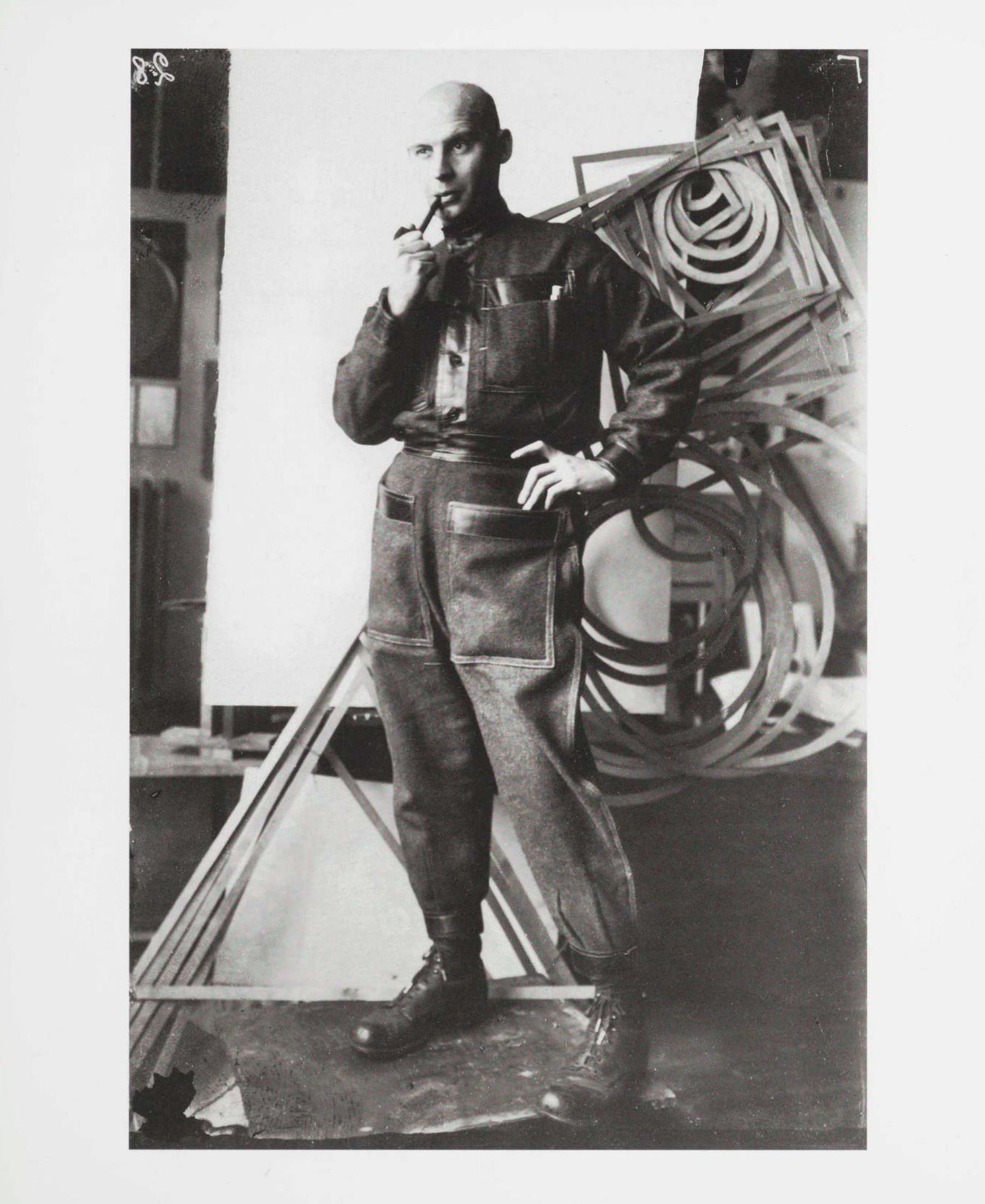

In the course of 1921, the Constructivists decided that what they called their “laboratory period” of theoretical investigation and pursuit of a rigorously abstract art had reached its logical conclusion. They resolved henceforth to devote their talents and energies to the design and production of useful objects and products. Five years after arriving in Moscow, Rodchenko had assumed a leading role as artist, theorist, teacher, and administrator in the new culture. He now took decisive action in charting its future by embarking on a new career that would involve hint in virtually every domain of the applied arts, as well as photography and film. That remarkable career—unique for a modem artist who had first established his or her prominence in the traditional mediums of painting and sculpture—is extensively surveyed in the present exhibition. The sole notable exception is Rodchenko’s work in costume and set design for theater and film, much of which was ephemeral by nature, so that its surviving elements do not adequately represent his achievement.

One of the defining motives of modern art has been a mandate to pursue the internal logic of formal invention, however strange its outcomes might seem with respect to prior conventions. A second key motive has been to escape from the hermetic sophistication often perceived as arising from the first—to break down the barriers between high art and ordinary life, and to redefine art as an instrument of social and political change. Rodchenko’s work drew upon both motives, yielding extremes of rarefied abstraction on the one hand and, on the other, practical applications ranging from advertising and product design to propaganda photojournalism. What is particularly challenging is that both poles of his art were deeply rooted in both motives. The guiding aim of the present exhibition has been to grasp Rodchenko’s best work, in all of its varieties, as a whole.

At the end of the civil war, in 1921, the Bolsheviks found themselves in control of a thoroughly devastated country. Lenin’s prediction that the Revolution would unleash an international class war, with Russia in the vanguard, had failed. The economy had collapsed, industrial production had fallen 80 percent below the levels of 1913, hundreds of thousands were dying of famine, and the incipient proletariat in whose name the Revolution was won had all but ceased to exist. Lenin responded by relaxing the draconian policies of the civil war, under which virtually every resource had been commandeered for the state and the army, and by reintroducing a limited form of capitalist competition, which gradually revived the economy. The New Economic Policy, or NEP, persisted until 1928, when Joseph Stalin launched his First Five-Year Plan of forced industrialization and collectivization of agriculture.

Lenin’s decline into illness in 1922, followed by his death in January 1924, provoked a struggle for succession among Leon Trotsky, Nikolai Bukharin, and Stalin, whose ascendancy was not secure until at least 1927. Thus politically as well as socially and culturally, the early and mid-i920s in Russia, although filled with tension and uncertainty, were a period of relative openness, opportunity, and flux. The advent of NEP, however, diminished the relative institutional autonomy of the leftist avant-garde. Thereafter the vociferous but tiny group was obliged to compete more actively for attention and funds. Among its most formidable opponents was AKhRR (Assotsiatsiia khudozhnikov revoliutsionnoi Rossii—the Association of Artists of Revolutionary Russia), which was founded in 1922 by conservative adherents of nineteenth-century realist painting, who ultimately triumphed by establishing the style of Party-sponsored Socialist Realism in the 1930s.

In this contentious climate, several extraordinarily talented leftist artists formed Lef (Levyi front iskusstv, the Left Front of the Arts), whose voice was the magazine Lef (Left, 1923–25), followed by Novyi Lef (New left, 1927–28), both financed by Narkompros. In addition to its nominal leader, Mayakovsky, Lef included or was associated with (among others) writers Nikolai Aseev, Osip Brik, Boris Kushner, and Sergei Tret’iakov; filmmakers Sergei Eisenstein and Dziga Vertov; stage director Vsevolod Meyerhold; and Viktor Shklovsky (who, with Roman Jakobson, on the eve of the Revolution, had founded the Russian Formalist school of literary theory and criticism). Rodchenko, the house artist, designed all of the covers of Lef and Novyi Lef, and contributed to their contents as well.

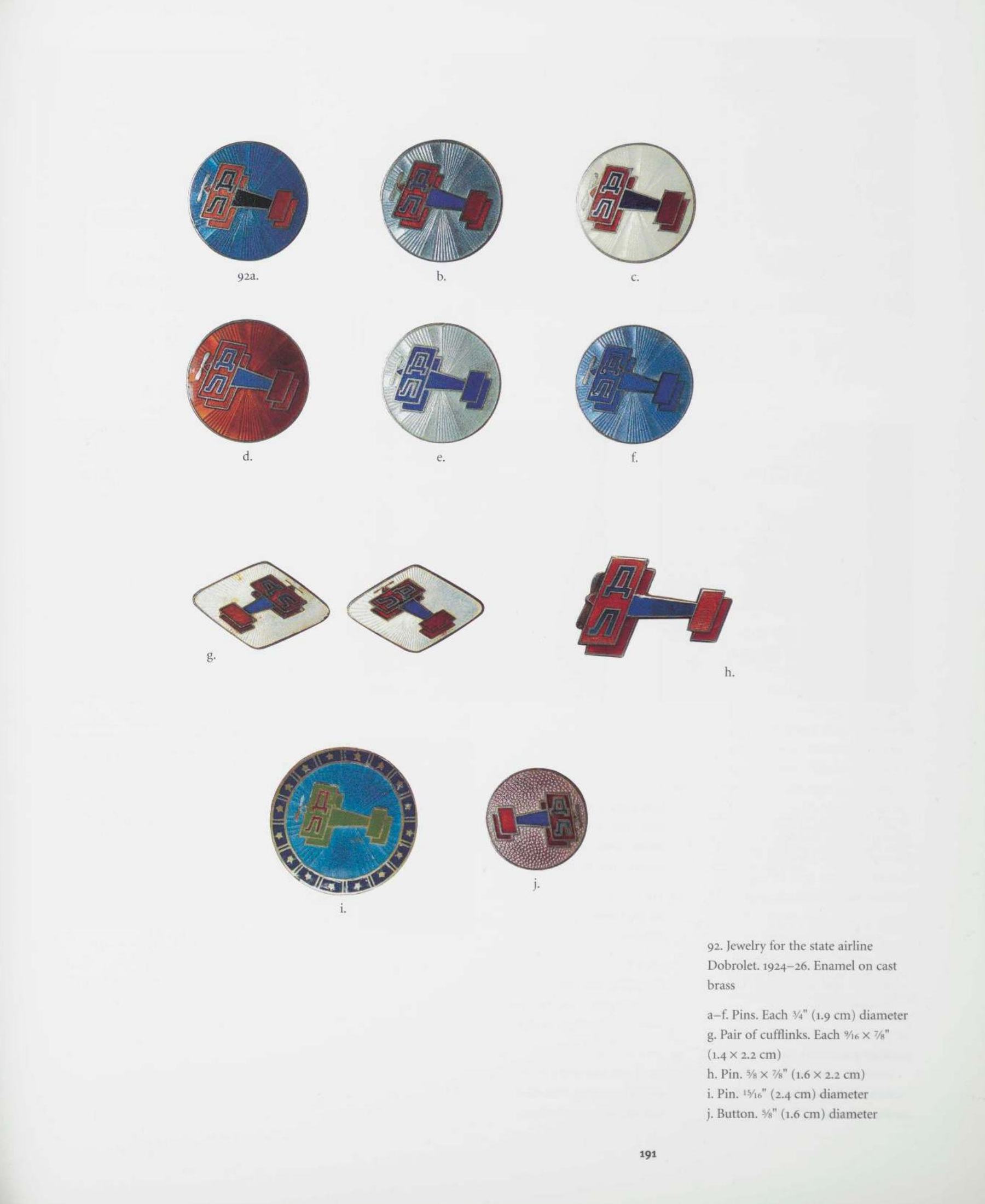

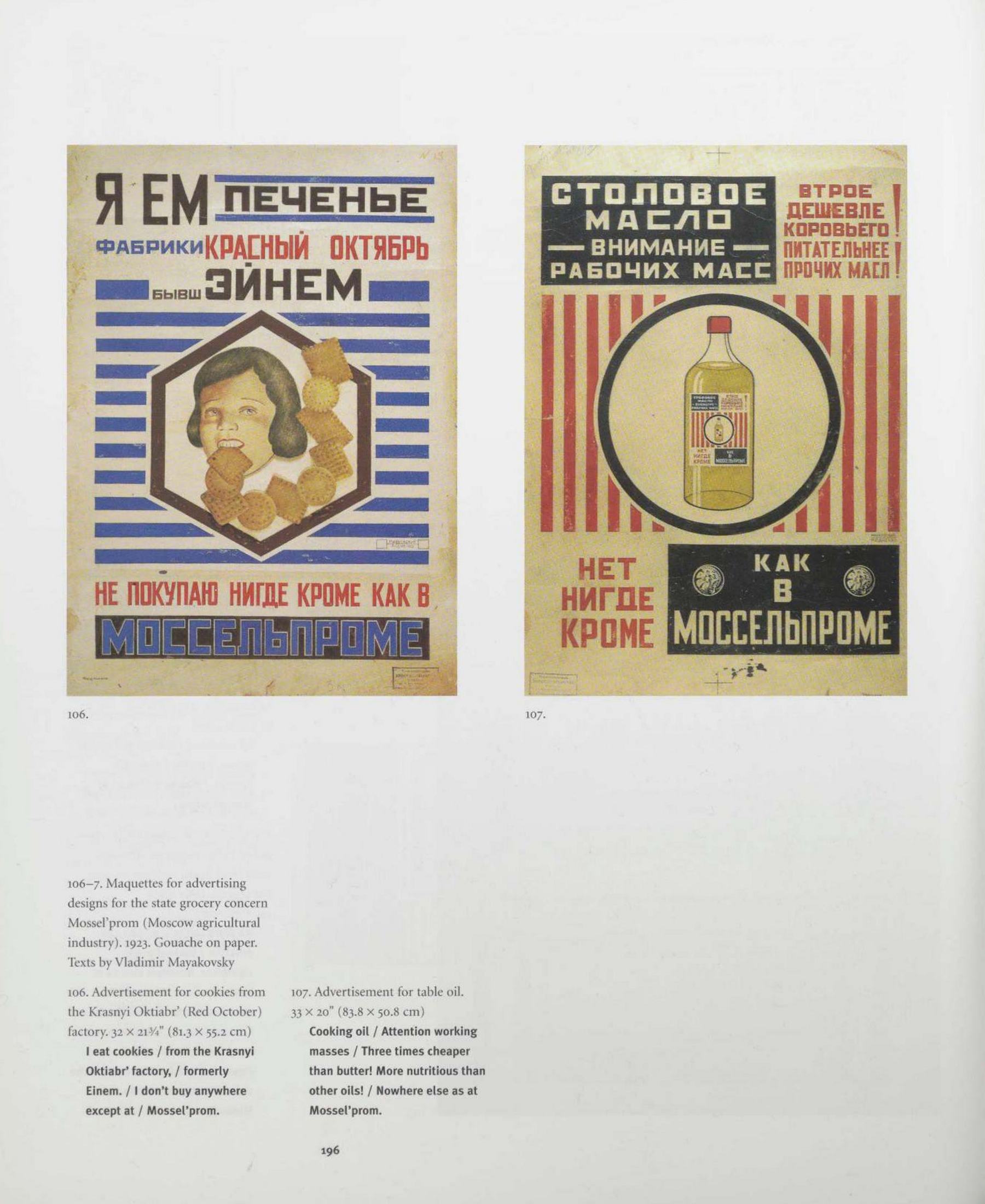

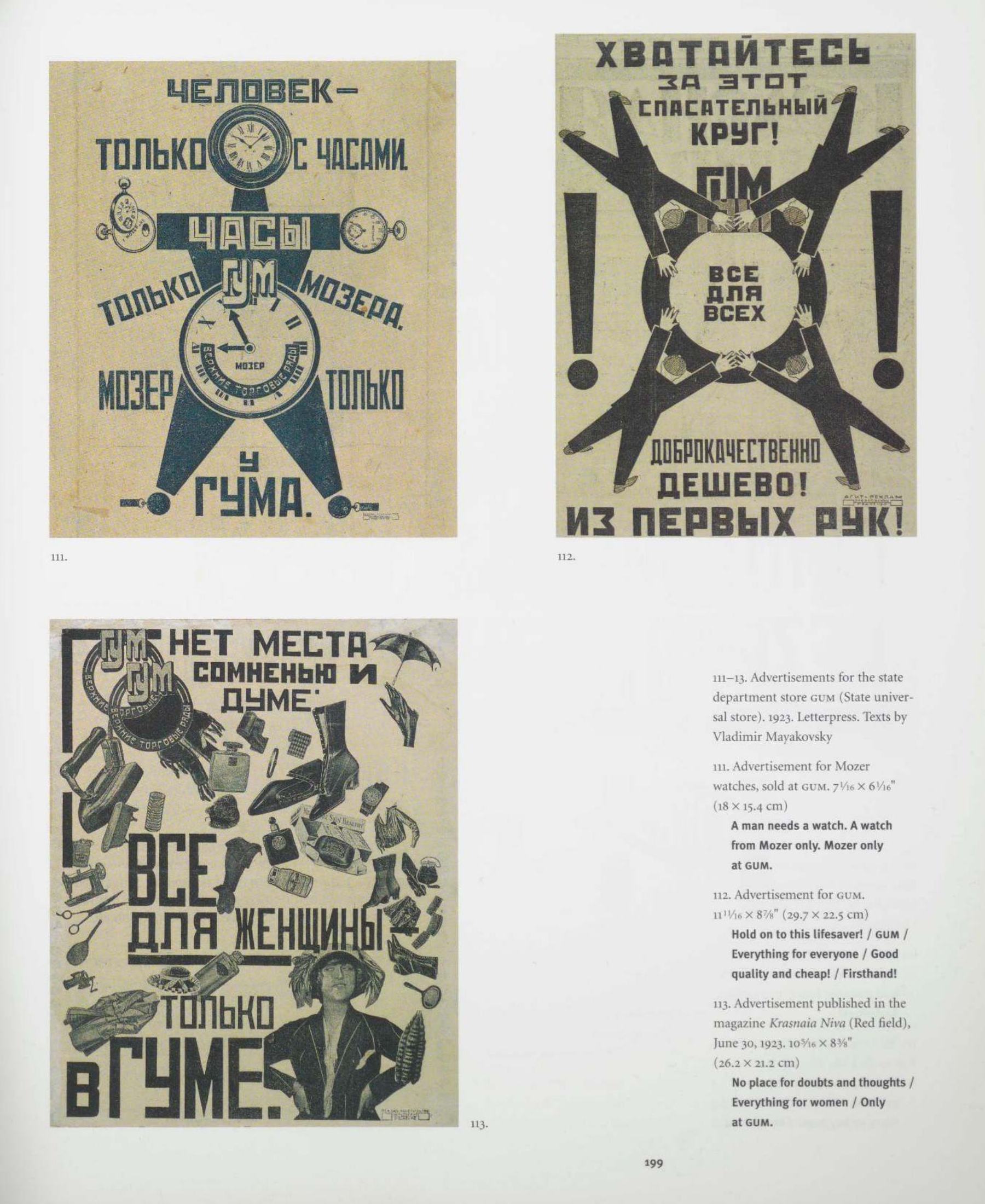

Lef strove to realize Marx’s social ideals, aiming at “the production of a new human being through art,” in Tret’iakov’s words.2 This collective project yielded an original and probing body of writing, which sought to synthesize Marxist materialism with advanced artistic experiment and Russian Formalist theory. Leah Dickerman’s essay on pages 62–99 analyzes Rodchenko’s sustained effort, from 1923 through the early 1930s, to put Lef principles into concrete practice. Among his most original achievements in this vein was his advertising work, often in collaboration with Mayakovsky, for Dobrolet (the state airline), Mossel’prom (the state grocery concern), and GUM (the state department store), which under NEP were obliged to compete for investors (in the case of Dobrolet) or customers.

____________

2 Sergei Tret’iakov, “Otkuda i kuda? (Perspektivy futurizma),” Lef no. 1 of 1923, p. 19;. Published in English as “Front Where to Where,” in Anna Lawton and Herbert Eagle, eds. and trams., Russian Formalism through Its Manifestoes, 1912–1928 (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1988), p. 208.

Stalin’s rise to power in the late 1920s ended the relative tolerance and diversity of the NEP era. Direcdy and indirectly, the Party revived the divisive rhetoric of class war, fomenting a climate of vituperative accusation In which the accuser shored up his standing as an ally of the “proletariat” by denouncing the “bourgeois” tendencies of the accused. The resulting cultural revolution, most intense from 1928 to 1931, discredited many adherents of the Revolution, including Mayakovsky, Rodchenko, and eventually the entire Lef circle, along with other remnants of the free-thinking intelligentsia. In 1932, when the First Five-Year Plan met its goals a year ahead of schedule, Stalin judged that the cultural revolution had done its work of replacing unreliable elements with loyal Party cadres. All artistic organizations were dissolved, eventually to be replaced by a single union of artists under Party control.

In 1929, Rodchenko joined the October group (Oktiabr’), which united a wide range of leftist artists in the aim of closing the gap between advanced art and the everyday life of the proletariat. In the latter part of the 1920s, photography was becoming Rodchenko’s principal occupation, and, as Peter Galassi shows in his essay on pages 100–137, he played a key role in establishing the lively vocabulary of European photographic modernism. When his photographs were first attacked as “bourgeois formalism” in April 1928, he defended himself vigorously. Over the next several years, however, he attempted to adapt to the changing circumstances, principally by devoting more and more of his efforts to propaganda photojournalism and graphic design. Doubtless Rodchenko and many other members of October were sincere in serving its goals, but it is difficult to believe that his expulsion from the group in 1932—again for “bourgeois formalism”— was anything but a desperate (and ultimately futile) attempt at self-preservation on the part of the group’s leadership.

Rodchenko was an original theorist of art, but he was not a political thinker. He remained steadfastly committed to the ideals of the Revolution, and his diaries suggest that he never understood the forces that drove him from the prominence he had enjoyed in the decade after 1917, and eventually rendered hint, as he put it, “an invisible man.”3 In the mid-t930s the artist who had boldly renounced painting in 1921 again began to paint—not abstract works but imaginary circus scenes. These paintings signal his alienation from the thrilling collective enterprise to which he had dedicated his life and from which he had drawn much of his unflagging inventiveness. In the 1940s he also painted abstract works of somewhat greater interest, but these too are omitted from the present exhibition. For as his diaries express, they are not products of a sustained creativity but of a painful and bewildering isolation, suffered by an artist whose work had been deeply rooted in collective goals. By the late 1930s Rodchenko and Stepanova were largely excluded from official culture, despite the design commissions they continued to receive from time to time. Like most Russians they suffered miserably during World War II, from which Rodchenko never fully recovered. He died in 1956, the year in which Nikita Khrushchev denounced Stalin’s crimes.

____________

3 Diary entry of May 28, 1945, in Aleksandr Rodchenko, Opyty dlia budushchego: dnevtiiki, stat'i, pis’ma, zapiski, ed. O. V. Mel'nikov and V. I. Shchennikov, compiled by A. N. Lavrent’ev and V. Rodchenko (Moscow: Grant’, 1996), p. 382. Trans. James West, in a manuscript commissioned by The Museum of Modem Art.

Rodchenko’s and Stepanova’s daughter Varvara Rodchenko begins her reminiscences of her father (pages 138–43) with an excerpt from her mother’s diary recording a visit from Alfred Barr in January 1928. The evolution of Barr's view of Rodchenko’s work is suggestive of its critical fortune generally. Later in 1928, Barr published an essay on the Lef group, stressing the political dimension of its art and theory.4 In the ambitious Cubism and Abstract Art exhibition at The Museum of Modern Art in 1936, however, he presented Russian Constructivism as an episode of inspired formal innovation, largely dissociated from its revolutionary context. By then avant-garde art and artists had been suppressed in ihe Soviet Union, and the continuing international influence of Constructivism increasingly dissolved its historical and political identity within a broad and vaguely defined stream of geometric abstraction. It was not until the 1960s that a growing concern among scholars for the historical context and ideological implications of all works of art brought a new outlook to bear on Constructivism—of all artistic movements perhaps the most thoroughly embroiled in politics. At the same time, both Russian and Western scholars began the work of reconstructing and making sense of the very complex historical record—a process greatly accelerated by the collapse of the Soviet Union and the consequent opening or casing of many paths of inquiry. This exhibition and book are inconceivable without that work, and aim to further it, for it is still very much underway.

____________

4 Alfred H. Barr, Jr., "The LEF and Soviet Art,” reprinted from Transition (Fall 1928) in Defining Modern Art: Selected Writings of Alfred H. Barr, Jr., ed. Irving Sandler and Amy Newman (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1986), pp. 138–41.

Sample pages

Download link (pdf, yandexdisk; 73,6 MB).

The electronic version of this issue is published only for scientific, educational or cultural purposes under the terms of fair use. Any commercial use is prohibited. If you have any claims about copyright, please send a letter to 42@tehne.com.

29 ноября 2021, 17:25

0 комментариев

|

Партнёры

|

Комментарии

Добавить комментарий